Abstract

Three experiments were conducted to examine the interaction of overexpectation treatment and trial massing using a Pavlovian fear conditioning procedure with rats. In first-order conditioning, Experiment 1 found the overexpectation effect (i.e., decreased conditioned responding to a cue after compound training when the elements were previously reinforced), the trial spacing effect (i.e., decreased responding to a cue when reinforced trials are massed), and a counteraction between overexpectation treatment and trial massing (i.e., an alleviation of the decrement in responding seen with overexpectation treatment or trial massing alone when the two treatments are conjointly administered). Experiment 2 replicated Experiment 1 with the critical treatments embedded within a sensory preconditioning preparation. The overexpectation effect, the trial spacing effect, and the mutual counteraction of overexpectation treatment and trial massing all proved significant. In Experiment 3, either the nontarget conditioned stimulus of overexpectation treatment or the excitatory context resulting from trial massing was extinguished. Results are best explained by the extended comparator hypothesis (J. C. Denniston, H. I. Savastano, & R. R. Miller, 2001).

Keywords: cue competition, overexpectation, trial massing, counteraction

The overexpectation effect is a decline in conditioned responding to each element of a pair of well-established conditioned stimuli (CSs), originally reinforced elementally (A–US/X–US), observed as a result of their being given further reinforcement in compound (AX–US; Rescorla, 1970). Rescorla and Wagner (1972) provided the first model that could account for overexpectation. This model asserts that overexpectation occurs because the expected unconditioned stimulus (US) based on all cues present is greater than the US that actually occurs during compound conditioning. Because both CS A and CS X are typically trained to asymptote during the initial elemental training, the US expectation based on the sum of the expectations evoked by CS A and CS X when they are paired should be a doubly strong US. According to Rescorla and Wagner, during compound conditioning trials, CS A and CS X should both lose associative strength to the US until the sum of their associative strengths equals the maximum allowable associative strength supportable by the US experienced on each compound trial. This decrement in X–US associative strength results in a loss of conditioned responding to CS X when presented alone on subsequent tests.

The extended comparator hypothesis (ECH; Denniston, Savastano, & Miller, 2001) can also account for the overexpectation effect but through a very different mechanism that emphasizes competition at the time of testing rather than at the time of training. The ECH assumes that associations are formed between all stimuli (including outcomes) that are present during training. There are three primary associations: the conventional target stimulus–outcome association (Link 1), the target stimulus–comparator stimulus association (Link 2), and the comparator stimulus–outcome association (Link 3). A comparator stimulus is any stimulus present during training other than the target cue or outcome. At test, a comparator process determines the level of responding that will be observed. Conditioned responding increases with the strength of US representation directly activated by the target–US association (Link 1) and decreases with the US representation indirectly activated by the target–comparator association and the comparator–US association (i.e., the product of Links 2 and 3). The ECH suggests that, during compound conditioning such as in overexpectation treatment, CS A becomes a comparator stimulus to the target CS X, because AX–US trials strengthen the X–A association (Link 2), which in turn results in less excitatory responding to CS X (because of the stronger indirect representation of the US outcome) than when CS X does not have an effective comparator stimulus. That is, the ECH posits that the overexpectation effect occurs because the target CS becomes strongly associated with a well-established CS during the AX–US trials. Of course, reciprocally, X should also decrease responding to A.

Thus, both the Rescorla–Wagner model and the ECH predict the basic overexpectation effect. One way to differentiate between these two accounts is to manipulate the interval between the AX–US trials. Given elemental conditioning (i.e., X–US pairings), both models anticipate diminished responding to the elemental cue with massed as opposed to spaced training trials (i.e., the trial spacing effect; Barela, 1999). Both models assume that the trial spacing effect arises from high rates of reinforcement of the context when the trials are massed, which allows the context to form a strong association with the US. According to the Rescorla–Wagner model, when trials are massed, the context competes with X for association to the US. According to the ECH, when trials are massed, the context comes to function as an effective comparator stimulus leading to decreased behavioral control by the target.

Although the ECH and Rescorla–Wagner models predict similar diminished responding for either trial massing or overexpectation treatment, they differ in the predicted consequences when the two treatments are combined (i.e., massed AX–US trials). The Rescorla–Wagner model anticipates that the context and A will both compete with X, resulting in a summation of their individual debilitating effects on responding to X. This should result in less responding to target CS X than would be predicted from massed trials alone (i.e., massed X–US trials) or overexpectation treatment alone (i.e., spaced AX–US trials).

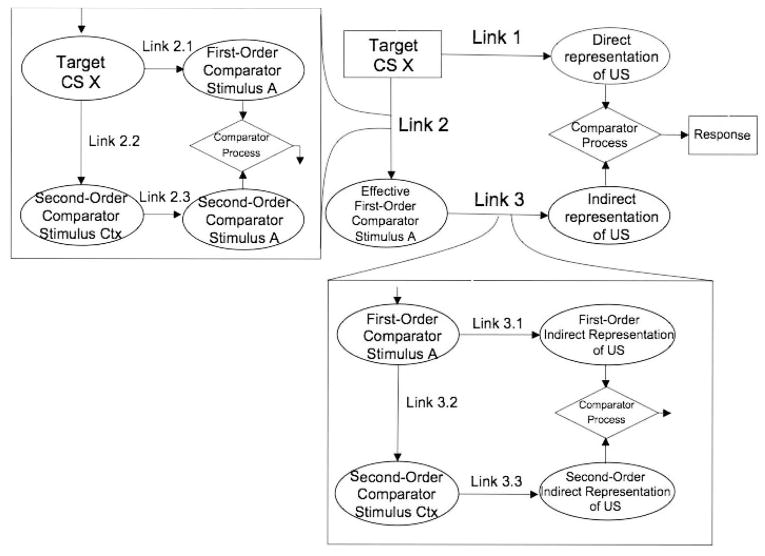

In contrast, the ECH anticipates that, when overexpectation training is conducted with massed trials, the two debilitating treatments should counteract each other and result in conditioned responding that is stronger than that observed with either debilitating treatment alone. With massed AX–US overexpectation trials, X acquires two strong comparator stimuli (i.e., A and the context), which are also associated with each other. The ECH allows these comparator stimuli to also serve as comparator stimuli for each other and, consequently, compete for potential to interact with X. Figure 1 is a diagram of the ECH in which CS A is a first-order comparator stimulus to target CS X, and the context functions as a comparator stimulus for A (i.e., a first-order comparator stimulus for A and, because A modulates responding to X, a second-order comparator stimulus for X). With compound, massed trials, Link 2.2 (CS X–context) and Link 3.2 (context–CS A) are strengthened, both of which attenuate A's potential to decrease responding to X. Concurrently, the context also serves as the first-order comparator stimulus to the target CS, X, and CS A serves as the second-order stimulus. For that reason, when trials are massed during overexpectation treatment, the second-order comparator effects of the context and CS A will effectively down-modulate the first-order comparator effects of each other, thereby allowing target CS X to exert more behavioral control. This should result in more conditioned responding to target CS X than would be expected from elemental massed trials or overexpectation treatment alone. We call this sort of phenomenon a counteraction effect. The observation of this counteraction effect would be supportive of the ECH account of overexpectation, whereas a summation of the debilitating consequences of overexpectation treatment and trial massing would be supportive of the Rescorla–Wagner account.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the extended comparator hypothesis with A as the first-order comparator stimulus and context as the second-order comparator stimulus. CS = conditioned stimulus; Ctx = context. Rectangles indicate test stimulus and response; ovals indicate mental representations; diamonds indicate comparator mechanism.

Consistent with the ECH explanation, counteraction effects have been observed between overshadowing and trial massing (Stout, Chang, & Miller, 2003), overshadowing and long-duration CSs (Sissons, Urcelay & Miller, 2008; Urushihara, Stout, & Miller, 2004), overshadowing and degraded contingency (Urcelay & Miller, 2006), overshadowing and latent inhibition (Blaisdell, Bristol, Gunther, & Miller, 1998), overshadowing and overtraining (Stout, Arcediano, Escobar, & Miller, 2003), and overshadowing and partial reinforcement (Urushihara & Miller, 2007; see Wheeler & Miller, 2008, for a review of these counteraction effects). Note that all these treatments involve the simultaneous establishments of two comparators for the target cue—namely, the overshadowing cue and the training context. Similar counteraction effects are observed when two punctate blocking cues are used (Witnauer, Urcelay, & Miller, 2008), but no counteraction effects have been reported with overexpectation as opposed to common cue competition effects such as overshadowing and blocking. Thus, one objective of this series was to determine whether a counteraction between trial massing and overexpectation would be observed.

Experiment 1

In Experiment 1, we sought to demonstrate the overexpectation effect and the trial spacing effect and to assess the possible counteraction of these two effects in Pavlovian first-order fear conditioning. All groups received X–US and A–US elemental conditioning trials in Phase 1. These Phase 1 trials had intermediate trial spacing (i.e., neither strongly massed or spaced), as trial spacing was a critical manipulation of Phase 2, not Phase 1. In Phase 2, select groups experienced no treatment, massed or spaced reinforced trials with an AX compound, or X alone (see Table 1). Our basic control for the overexpectation effect was no treatment in Phase 2. This allowed us to assess behavioral control as a function of Phase 1 alone. An additional control for overexpectation was further elemental trials in Phase 2 as opposed to compound trials. This control allowed us to concurrently examine the trial spacing effect as a consequence of spacing or massing the Phase 2 trials. Parameters chosen for this experiment were modeled closely after those used in Blaisdell, Denniston, and Miller (2003), in which they demonstrated the overexpectation effect as indicated by a comparison of their overexpectation group with three different control groups. In that study, all groups received the same training in Phase 1: A–US pairings, X–US pairings, and B nonreinforced presentations. In the overexpectation group, A and X were reinforced in compound in Phase 2. The first control they used assessed the possibility of a generalization decrement interpretation of overexpectation by training the target CS in compound with a novel CS during Phase 2. If generalization decrement was an issue, responding in this group should have shown a decrement in responding to the target CS, compared with a group that did not receive compound reinforcement in Phase 2. The second control group used by Blaisdell et al. was an acquisition control wherein the number of Phase 2-signaled reinforcements was equated but training was not compounded; only the target CS was presented. Blaisdell et al.'s third control group was also given elementally reinforced presentations in Phase 2, but the stimulus was a previously nonreinforced CS (B). Blaisdell et al. successfully demonstrated an overexpectation effect compared with all three of these control groups; that is, responding to the target stimulus in the overexpectation group was weaker than in each of the control groups. Because of the similarity of our preparation to that of Blaisdell et al., we did not see the need to include all of their control groups in our studies. Instead we included a replication of their second control group; that is, a group for which A was omitted during Phase 2 as well as a group that received Phase 1 training only. Thus a 2 (X–US vs. AX–US) × 2 (spaced vs. massed Phase 2 trials) + 1 (acquisition control [Acq. Ctrl.]) design was used to evaluate the ECH and Rescorla–Wagner account of overexpectation.

Table 1. Design Summary of Experiment 1.

| Group | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Test | ECH | RW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X massed | 6 A–US/6 X–US (intermediate) | 8 X–US (massed) | X | Cr | Cr |

| X spaced | 6 A–US/6 X–US (intermediate) | 8 X–US (spaced) | X | CR | CR |

| AX massed | 6 A–US/6 X–US (intermediate) | 8 AX–US (massed) | X | CR | cr |

| AX spaced | 6 A–US/6 X–US (intermediate) | 8 AX–US (spaced) | X | Cr | Cr |

| Acq. Ctrl | 6 A–US/6 X–US (intermediate) | Handling | X | CR | CR |

Note. Numbers refer to the total number of each trial type across all days of treatment. Intermediate, massed, and spaced refer to trial spacing. ECH = extended comparator hypothesis (Denniston et al., 2001) predictions; RW = Rescorla and Wagner's (1972) model predictions; X = elemental target presentations of X in Phase 2; A = tone; X = click train, and US = footshock; CR, Cr, and cr denote strong, intermediate, and weak levels of behavioral control, respectively, based on simulations of the ECH and RW; AX = compound presentations of A and X in Phase 2; Acq. Ctrl. = acquisition control, which received no relevant treatment in Phase 2.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were 30 male and 30 female Sprague–Dawley, experimentally naïve, young adult rats, bred in our colony. Body weight range was 189–248 g for females and 294–373 g for males. Subjects were individually housed and maintained on a 16:8-hr light–dark cycle, with experimental sessions occurring roughly midway through the light portion of the cycle. All subjects were handled for 30 s three times per week from weaning until the initiation of the study. Subjects had free access to food in the home cage. One week before initiation of the experiment, water availability was progressively reduced to 30 min/day, provided shortly after any scheduled treatment.

Apparatus

The apparatus consisted of 12 operant chambers, each measuring 30.5 cm × 27.5 cm × 27.3 cm (length × weight × height). All chambers had clear Plexiglas ceilings and side walls, and metal front and back walls. On one metal wall of each chamber, there was an operant lever, and adjacent to it a niche (4.5 × 4.0 × 4.5 cm) centered 3.3 cm above the floor where a drop (0.04 cc) of tap water could be presented by a solenoid valve. Chamber floors were 4-mm grids spaced 1.7 cm apart center-to-center, connected with NE-2 neon bulbs, which allowed constant-current footshock to be delivered by means of a high voltage AC circuit in series with a 1.0-MΩ resistor. All chambers were housed in sound- and light-attenuating cubicles. Each chamber was dimly illuminated by a (#1820) houselight. Additionally there was a 60-W (nominal at 120 VAC, driven at 60 VAC) incandescent bulb that was illuminated for 0.5 s simultaneously with each water reinforcement. Chamber assignments within each of the four groups were counterbalanced. Three 45-Ω speakers mounted on different interior walls of each environmental chest could deliver either a high-frequency complex tone (3000 and 3200 Hz) 8 dB(C) above the ambient background, a 6-Hz click train 8 dB above background, or a white noise stimulus 8 dB(C) above background, all 10 s in duration. The ambient background sound of 78 dB was produced primarily by a ventilation fan. In all three experiments, the clicks were used as CS X and tone was used as CS A. The white noise was used only in Experiments 2 and 3. A 1.0-mA, 0.5-s footshock, which served as the US, could be delivered through the grid floors.

Procedure

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of five groups (ns = 12), counterbalanced for sex and operant chamber. Shaping, reshaping, and testing were conducted in Context 1, whereas training was conducted in Context 2. Different contexts were used for testing and training to minimize any potential associative strength of the training context from summating with the associative strength of the target CS at test. Note that the ECH specifies that the context of training, not the context of testing, is what gets compared with the target. Thus, testing outside of the training context minimizes ambiguity concerning which stimulus the subject is responding to at test. Context 1 was characterized by the levers being activated (so that the rats could be reinforced for pressing), no odor cue being present, and a smooth Plexiglas surface being placed over the grid floor. Context 2 was characterized by the lever being inactivated and there being a wooden block scented with 2 drops of mint (Gallipot brand methyl salicylate) within the sound-attenuating environmental chest but outside the operant chamber. Moreover, Context 2 had the Plexiglas floors removed from the grids, and the specific chamber serving each rat as Context 1 was always different from that serving that rat as Context 2.

Shaping

Before Phase 1 of training, 5 days of acclimation to the apparatus and shaping of lever press behavior were conducted in daily 60-min sessions in Context 1. Subjects were shaped to lever press for a 0.04-cc drop of water on a variable-interval 20-s (VI-20 s) schedule in the following manner. On Days 1 and 2, a fixed-time 120-s schedule of noncontingent water delivery was in force along with a continuous reinforcement schedule. On Day 3, noncontingent reinforcement was discontinued, and subjects were trained on the continuous reinforcement schedule alone. Subjects that made fewer than 50 responses on this day were given a hand-shaping session later in the same day. On Days 4 and 5, a VI-20 s schedule was imposed. This schedule of reinforcement prevailed throughout the remainder of the experiment in Context 1, including testing. No nominal stimulus was presented during this phase. Water presentation was always accompanied by a 0.5-s presentation of the light.

Phase 1

On Days 6–8, all subjects experienced two X–US and two A–US trials per day, with trial order pseudorandomized, for a total of six A–US and six X–US trials in Context 2. Trials were separated from each other by a mean intertrial interval (ITI) of 196 s (US termination–CS onset), within the 13.7-min training session. Trials were initiated at 98, 304, 550, and 716 s. The footshock started 0.5 s before termination of the 10-s CS; thus, the CS and US coterminated.

Phase 2

On Day 9, 48 of the subjects were divided into two conditions based on the spacing of Phase 2 trials (and, consequently, session length). In the spaced condition, trials occurred at 8.00, 24.20, 37.40, 56.60, 74.80, 89.00, 104.20, and 121.40 min in a 129.00-min session. In the massed condition, trials occurred 0.33, 1.17, 1.88, 2.83, 3.78, 4.50, 5.50, and 6.17 min in a 6.67-min session. These two conditions were each orthogonally divided into two groups, depending on whether the target was trained elementally (X massed and X spaced groups) or in compound (AX massed and AX spaced groups). Additionally, the Acq. Ctrl. group was placed in the transportation cart and then placed back into the homecage to equate for handling.

Reshaping

On Days 10–12, all subjects experienced a 1-hr session in Context 1 to restabilize lever pressing on the VI-20 s schedule.

Test

On Day 13, suppression of baseline responding during presentation of the target CS was assessed in all groups in Context 1. Each subject received four nonreinforced 60-s presentations of the CS during a 25-min session with the CS onsets occurring at 5, 11, 17, and 23 min into the session. The response rates (number of lever presses per minute) during the 120-s period preceding each CS exposure (pre-CS score) and during the 60-s CS exposure (CS score) were recorded.

Data Analysis

The suppression ratio (Annau & Kamin, 1961) of each subject was calculated by the formula CS/(CS + pre-CS), where CS is the mean rate of lever pressing across all four of the 60-s CS presentations and pre-CS is the mean rate of lever pressing during the first 120-s pre-CS period. This ratio was used as an index of the fear induced by presentation of the target CS. Alpha was set at 0.05 for all inferential tests. Effect sizes were calculated with Cohen's f (Myers & Well, 2003).

Results and Discussion

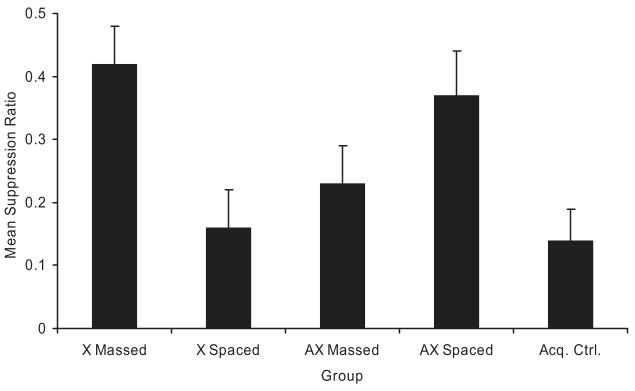

Figure 2 illustrates mean suppression ratios to the target CS observed in Experiment 1. Strong suppression was observed in the Acq. Ctrl. group, demonstrating that Phase 1 training was sufficient to elicit freezing behavior to the target stimulus. More suppression was observed in the X spaced group than in the X massed group, thereby demonstrating the basic trial spacing effect. Less suppression in the AX spaced group, compared with the X spaced group, was observed, thereby demonstrating the overexpectation effect. Suppression levels in the AX massed and X massed groups were reversed in their ordinal positions compared with the AX spaced and X spaced groups. That is, more suppression was observed in the AX massed group than in the X massed group, and less suppression was observed in the AX spaced group than in the X spaced group. This suggests a mutual counteraction of overexpectation treatment and trial massing. These observations were largely supported by the following analyses.

Figure 2.

Results of Experiment 1. Mean suppression ratios to the target cue (X) at test. Note that, with suppression ratios, lower values reflect greater conditioned suppression. Error bars represent the standard error of the means. See text and Table 1 for details. Acq. Ctrl. = acquisition control.

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) conducted on baseline lever pressing during the 120 s before the first test trial detected an effect of treatment group, F(4, 55) = 2.95. This indicates that there were differences among groups in fear of the test context; however, the differences were not in accordance with either the ECH or Rescorla–Wagner model predictions concerning behavioral control by the target cue, nor did it appreciably correlate with the CS suppression ratios. Group rates of lever pressing during the 120 s immediately preceding the first test trial were as follows: 31 for the X massed group, 24 for the X spaced group, 29 for the AX massed group, 37 for the AX spaced, and 38 for the Acq. Ctrl. group. Lower rates of lever pressing are an indication of greater fear. A similar ANOVA was conducted on the suppression ratios. This analysis revealed an effect of treatment group, F(4, 55) = 4.43, MSE = 0.04, Cohen's f = 0.48.

Planned comparisons were conducted to test specific hypotheses. A comparison between the X spaced and the X massed groups revealed less suppression in the elementally trained (i.e., control) groups when trials were massed than when trials were spaced, F(1, 55) = 9.97, thereby documenting a trial spacing effect. A comparison between the AX spaced and Acq. Ctrl. groups demonstrated the overexpectation effect using a control group that received no Phase 2 training, F(1, 55) = 7.03. A comparison between the X spaced and AX spaced groups revealed less suppression in the spaced group that received overexpectation treatment compared with the spaced group that received further elemental training in Phase 2, F(1, 55) = 6.27. A similar comparison between the X massed and AX massed groups proved significant, F(1, 55) = 5.18, reflecting an alleviation of the trial massing deficit by administration of overexpectation treatment. However, a comparison between the AX massed and AX spaced groups failed to reach significance, p = .11, although the tendency of the difference between these groups was in the expected direction. Despite the lack of statistical significance in this last comparison, the fact remains that there was no summation of the deleterious effects of trial massing and overexpectation on responding to X. Combined with the significant difference between the X massed and AX massed, this makes it reasonable to suggest that we observed counteraction between trial massing and overexpectation treatment.

Experiment 1 demonstrated the trial spacing effect and the overexpectation effect. More important, ordinal reversal of suppression between the X massed and AX massed groups, compared with the X spaced and AX spaced groups, evidenced the counteraction of trial massing and overexpectation treatment. That is, with massed trials and overexpectation treatment, suppression to the target CS tended to be greater than with either deleterious treatment alone. These results are supportive of the predictions made by the ECH (Denniston et al., 2001).

Experiment 2

Although the results of Experiment 1 were consistent with the predictions of the ECH, we decided to test a further prediction of the ECH concerning the consequences of posttraining extinction of the target CS's two putative comparator stimuli (CS A, because of overexpectation treatment, and the context, because of trial massing in Phase 2). Our expectation was that posttraining extinction of one of the two comparator stimuli would release the remaining comparator stimulus, thereby allowing it to decrease responding to X. However, previous research in our laboratory has shown that it is very difficult to reduce conditioned responding to a previously reinforced stimulus without nonreinforced presentations of the target stimulus itself or devaluation of the outcome (e.g., Denniston, Miller, & Matute, 1996; Miller & Matute, 1996; Oberling, Bristol, Matute, & Miller, 2000). This has been referred to as the principle of biological significance. One way to circumvent this problem is to conduct training in a manner that prevents the target stimulus from becoming biologically significant (i.e., coming to control behavior) before any posttraining manipulation. Toward this end, we used a sensory preconditioning preparation (Brogden, 1939) in which the stimuli were paired with a neutral outcome during training. Before testing, the neutral outcome was paired with a biologically significant outcome (i.e., foot-shock) to motivate behavior that we could observe.

First, we sought to replicate Experiment 1 within a sensory preconditioning preparation to make certain that we could observe the basic effects of Experiment 1 in this paradigm. That is, Experiment 2 was designed to demonstrate overexpectation, the trial spacing effect, and the mutual counteraction of the two using a sensory preconditioning preparation. Of note, the number of Phase 2 trials was increased from 8 to 18 in the following sensory preconditioning experiments. This was done on the assumption that the neutral surrogate outcome was less salient than the biologically significant US used in Experiment 1, thereby requiring more trials to enter into asymptotic association with the context. Additionally, we eliminated the Acq. Ctrl. control group and retained only the X spaced control group.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were 24 female (188–241 g) and 24 male (238–357 g) Sprague–Dawley, experimentally naïve, young adult rats, bred in our colony. The animals were housed and maintained as in Experiment 1. The apparatus and stimuli were identical to those used in Experiment 1, except that a 5-s white noise, 8 dB(C) above background served as the neutral surrogate outcome (S).

Procedure

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of four groups (n = 12), counterbalanced for sex and operant chamber. Shaping, first-order conditioning, reshaping, and testing were conducted in Context 1, whereas Phases 1 and 2 were conducted in Context 2. Shaping, reshaping, testing and the data analysis were identical to those in Experiment 1. Phase 1 was also identical, except that the footshock was replaced by 5-s presentations of the S outcome that onset at the termination of the CSs (see Table 2).

Table 2. Design Summary of Experiment 2.

| Group | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | First-order conditioning | Test | ECH | RW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X massed | 6 A→S/6 X→S (intermediate) | 18 X→S (massed) | 8 S→US | X | Cr | Cr |

| X spaced | 6 A→S/6 X→S (intermediate) | 18 X→S (spaced) | 8 S→US | X | CR | CR |

| AX massed | 6 A→S/6 X→S (intermediate) | 18 AX→S (massed) | 8 S→US | X | CR | cr |

| AX spaced | 6 A→S/6 X→S (intermediate) | 18 AX→S (spaced) | 8 S→US | X | Cr | Cr |

Note. Numbers refer to the total number of each trial type across all days of treatment. Intermediate, massed, and spaced refer to trial spacing. CR, Cr, and cr denote strong, intermediate, and weak levels of behavioral control, respectively, based on simulations of the ECH and RW; ECH = extended comparator hypothesis (Denniston et al., 2001) predictions; RW = Rescorla and Wagner (1972) model predictions; X = elemental target presentations of X in Phase 2; A = tone; S (white noise) = surrogate outcome; X = click train; US = footshock; AX = compound presentations of A and X in Phase 2.

Phase 2

On Days 9–11, the subjects were divided into two conditions by trial spacing (and, consequently, session length). In the spaced condition, trials occurred at 8.00, 24.20, 37.40, 56.60, 74.80, and 89.00 min in 97.00-min sessions. In the massed condition, trials occurred at 0.33, 1.17, 1.88, 2.83, 3.78, and 4.50 min in a 5.00-min session. These two conditions were orthogonally divided into two groups, depending on whether the target was trained elementally (X massed and X spaced groups) or in compound (AX massed and AX spaced groups) The 5-s surrogate outcome was presented immediately on termination of the 10-s CS.

Phase 3 (First-order conditioning)

On Days 12 and 13, all subjects received four S–US pairings that occurred at 12, 22, 36, and 48 min into the 60-min session, for a total of eight S–US pairings. The US was presented for 0.5 s immediately on termination of the S outcome. The mean ITI from US onset to US onset was 720 s.

Results and Discussion

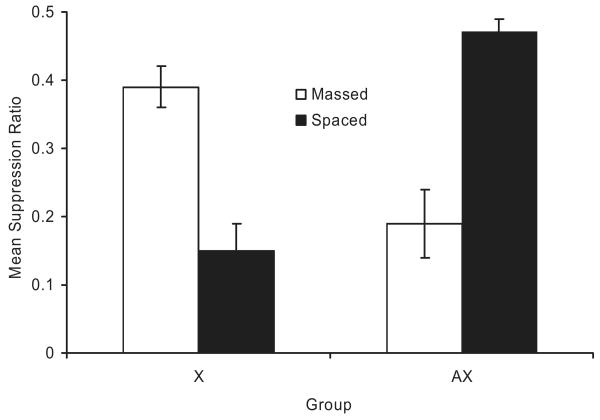

The results of Experiment 2 are depicted in Figure 3. One animal from the X spaced group was eliminated from the analyses because of a lack of baseline responding. As can be seen, Experiment 2 clearly demonstrated the overexpectation effect, the trial spacing effect, and the counteraction of the two effects. Less suppression in the AX spaced group compared with the X spaced group was observed, thereby demonstrating overexpectation. More suppression was observed in the X spaced group than in the X massed group, thereby demonstrating the trial spacing effect. Suppression levels in the AX massed and X massed groups were reversed in their ordinal positions compared with the AX spaced and X spaced groups. This demonstrates the mutual counteraction of overexpectation treatment and trial massing. These observations are supported by the following analyses.

Figure 3.

Results of Experiment 2. Mean suppression ratios to the target cue (X) at test. Note that, with suppression ratios, lower values reflect greater conditioned suppression. Error bars represent the standard error of the means. See text and Table 2 for details.

A 2 × 2 ANOVA with training (X vs. AX) and trial spacing (spaced vs. massed) as main factors conducted on baseline responding during the 120 s before the first test trial yielded no significant main effect or interaction, all ps > .41. A similar ANOVA conducted on the suppression ratios revealed no main effects but did reveal an interaction between the two factors, F(1, 43) = 48.35, MSE = 0.017, Cohen's f = 1.003.

Planned comparisons using the overall error term from the ANOVA were conducted to assess the source of the interaction. A comparison between the X spaced and the X massed groups revealed less suppression when trials were massed than when trials were spaced, F(1, 43) = 21.17. A comparison between the X spaced and the AX spaced groups demonstrated less suppression in the group that received AX training, compared with the group that received X-alone training, when trials were spaced, F(1, 43) = 36.03. Critically, a similar comparison conducted on the X massed and AX massed groups proved significant, F(1, 43) = 14.50, reflecting a reversal in the ordinal position of suppression levels compared with the X spaced and AX spaced groups, indicating that A enhanced suppression in the massed condition. Similarly, a comparison between the AX spaced and AX massed groups detected a difference, F(1, 43) = 27.46, suggesting that the overexpectation effect is attenuated when trials are massed. In summary, the experiment clearly demonstrated a counteraction effect between trial massing and overexpectation treatment in that more conditioned suppression was observed when the two treatments were administered together relative to either treatment alone.

Experiment 3

Experiment 3 was designed to further test predictions of the ECH concerning the roles of representations of A and the context at the time of testing. According to the ECH, the counteraction between trial massing and overexpectation treatment observed in Experiments 1 and 2 results from the establishment of a second comparator stimulus (A) for X during Phase 2. Consequently, posttraining extinction of either comparator stimulus (A from overexpectation treatment or the context from trial massing) should result in a reversal of the counteraction produced by overexpectation treatment with massed trials. That is, extinction of A after AX–US massed trials should reduce conditioned suppression relative to a similarly trained group that receives no extinction of A. This would reflect an unmasking of the trial spacing effect. Likewise, extinction of the context after AX–US massed training should decrease conditioned suppression relative to a similarly trained group that received no extinction of the context. This constitutes an unmasking of the overexpectation effect. Extinction of A after overexpectation treatment conducted with spaced trials should result in a recovery from overexpectation (Blaisdell et al., 2003), that is, an increase in behavioral control by X, because there are no effective comparator stimuli left to down modulate responding. Extinction of the context after spaced overexpectation training should have little or no effect on responding to the target stimulus at test. This is because the context should not have become an effective comparator stimulus during training because of context extinction that occurred during the spaced compound–CS trials.

The original Rescorla–Wagner model (Rescorla & Wagner, 1972) does not make similar predictions regarding posttraining extinction of A or the context, because its predictions concerning overexpectation are based on a loss of associative strength during Phase 2 treatment. Once associative strength is lost, it cannot be regained by any means other than additional treatment with the CS present. However, a revision of the Rescorla–Wagner model has allowed it to account for retrospective revaluation effects on behavior (Van Hamme & Wasserman, 1994). We review these predictions, as well as those made by a revision of Wagner's (1981) sometimes-opponent process (SOP) model proposed by Dickinson and Burke (1996), in more detail in the General Discussion.

In this experiment, we gave overexpectation treatment to all groups. Phase 2 training was either massed or spaced and, orthogonally, groups received no extinction (NoE), extinction of A (AE), or extinction of the context (CtxE; see Table 3). The spaced NoE and massed NoE groups were included to replicate the counteraction effect and to control for nonassociative effects of handling and retention interval imposed on the extinction groups.

Table 3. Design Summary of Experiment 3.

| Group | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Extinction | First-order conditioning | Test | ECH | VHW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Massed NoE | 6 A→S/6 X→S (intermediate) | 18 AX→S (massed) | Handling | 8 S→US | X | CR | cr |

| Spaced NoE | 6 A→S/6 X→S (intermediate) | 18 AX→S (spaced) | Handling | 8 S→US | X | Cr | Cr |

| Massed AE | 6 A→S/6 X→S (intermediate) | 18 AX→S (massed) | 240 A- | 8 S→US | X | Cr | Cr |

| Spaced AE | 6 A→S/6 X→S (intermediate) | 18 AX→S (spaced) | 240 A- | 8 S→US | X | CR | CR |

| Massed CtxE | 6 A→S/6 X→S (intermediate) | 18 AX→S (massed) | Long Ctx | 8 S→US | X | cr | Cr |

| Spaced CtxE | 6 A→S/6 X→S (intermediate) | 18 AX→S (spaced) | Long Ctx | 8 S→US | X | cr | Cr |

Note. Numbers refer to the total number of each trial type across all days of treatment. Intermediate, massed, and spaced refer to trial spacing. CR, Cr, and cr denote strong, intermediate, and weak levels of behavioral control, respectively, based on simulations of the ECH and RW. ECH = extended comparator hypothesis (Denniston et al., 2001) predictions; VHW = Van Hamme and Wasserman (1994) model predictions; A = tone; S (white noise) = surrogate outcome; X = click train; US = footshock; NoE = no extinction; AE = extinction of A; CtxE = context extinction.

Method

Subjects

Subjects were 36 female (226–313 g) and 36 male (247–442 g) Sprague–Dawley, experimentally naïve, young adult rats, bred in our colony. The animals were housed and maintained as in the previous experiments. The apparatus and stimuli were identical to those used in Experiment 2.

Procedure

Subjects were randomly assigned to one of six groups (ns = 12), counterbalanced for sex and operant chamber. Shaping, first-order conditioning, reshaping, and testing were conducted in Context 1, whereas Phases 1 and 2 and extinction were conducted in Context 2. Shaping, Phase 1, first-order conditioning, reshaping, and testing were all identical to Experiment 2. Phase 2 was also identical, except that all groups received AX–S pairings (see Table 3).

Phase 3 (extinction)

On Days 12–15, the spaced and massed conditions were orthogonally divided into three groups by extinction type. Subjects in the AE condition received daily 12-min sessions in Context 2 and during each session experienced 60 nonreinforced presentations of A (a total of 240 exposures). The first trial started 1 s after the session began, and the ITI (from CS termination to CS onset) was 1, 2, or 3 s. The last CS finished 1 s before the end of the session. The trials were massed to minimize context extinction. Preliminary conditioned suppression research in our laboratory has found that multiple hours of context exposure are necessary to affect responding to a cue trained in that context. Thus, the 48 min of context exposure experienced by subjects in this group should have had no appreciable affect on behavioral control by X. Subjects in the CtxE condition experienced daily 150-min sessions in Context 2 with no nominal stimulus presentations. Experimental chambers were opened every 30 min to ensure that the rats were not sleeping. Subjects in the NoE condition received identical handling but no time in the context to control for retention interval effects and handling.

Results and Discussion

On Day 13 (the second day of extinction treatment), 6 rats from the CtxE group received 60 A- trials because of an experimenter error. Previous observations in our laboratory found that at least 200 nonreinforced trials are necessary for extinction of a punctate stimulus of the present duration to sufficiently induce retrospective revaluation in our conditioned suppression preparation. Therefore, the animals that received the inadvertent treatment were not removed from the study. An analysis comparing the behavioral control by X at testing of the 6 subjects in the CtxE group that received these unintended exposures to A with the other six subjects that did not receive these exposures was conducted to assess the effect of these 60 A- trials. No difference was found, F(1, 22) = 0.03, p = .84; thus, we felt it safe to assume that the accidental exposure did not appreciably affect stimulus control by X. On the day of testing, 2 animals (one each from the spaced AE and massed NoE groups) failed to make any lever presses during the baseline period and therefore were eliminated from all analyses.

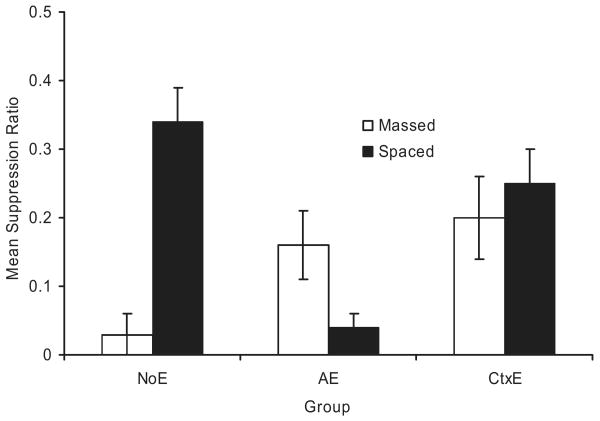

Figure 4 depicts mean suppression ratios observed in Experiment 3. Inspection of the figure suggests that more suppression occurred in the massed NoE group than in the spaced NoE group, thereby replicating the counteraction of overexpectation treatment and trial massing. In contrast, less suppression was observed in the massed AE group than in the massed NoE group, thereby demonstrating a weakening of the counteraction that was seen in the massed NoE group. Suppression was roughly equal across the two context extinction groups. However, the change relative to their respective NoE groups is the comparison of interest. Less suppression was observed in the massed CtxE group than in the massed NoE group, as expected by the ECH. These observations are supported by the following analyses.

Figure 4.

Results of Experiment 3. Mean suppression ratios to the target cue (X) at test. Note that, with suppression ratios, lower values reflect greater conditioned suppression. All subjects received overexpectation treatment in Phase 2. Error bars represent the standard error of the means. See text and Table 3 for details. NoE = no extinction; AE = extinction of A; CtxE = extinction of the context.

A 2 × 3 ANOVA with trial spacing (spaced vs. massed) and extinction treatment (NoE vs. AE vs. CtxE) as main factors, conducted on baseline responding during the 120 s before the first test trial, yielded no significant main effect or interaction, all ps > 0.08. A similar ANOVA was conducted on the total suppression ratio. This analysis revealed a main effect of extinction, F(2, 64) = 3.58, MSE = 0.03, and an interaction between the two factors, F(2, 64) = 9.60, MSE = 0.03, Cohen's f = 0.49.

We conducted planned comparisons using the overall error term from the ANOVA to assess the source of the interaction. A comparison between the massed NoE and spaced NoE groups revealed more suppression in the massed NoE group, F(1, 64) = 19.68, which echoes the counteraction of overexpectation with trial massing. An analysis of the reversal of the counteraction revealed more suppression in the spaced AE group than in the spaced NoE group, F(1, 64) = 18.61, demonstrating recovery from overexpectation resulting from extinction of the added cue. A comparison between the massed AE and massed NoE groups failed to achieve a conventional level of statistical significance with a two-tailed test, F(1, 64) = 3.34, p = .07; but the ordinal direction of the difference was in agreement with the prediction of the ECH. However, as predicted, there was less suppression in the massed CtxE group, compared with the massed NoE group, F(1, 64) = 6.15. As expected, no difference was found between the spaced CtxE and spaced NoE groups, p = .19.

Experiment 3 replicated the counteraction found in the previous experiments (the spaced NoE group vs. the massed NoE group). We observed a marginally significant reversal of the counteraction with extinction of A in the massed condition and a recovery from the overexpectation effect with extinction of A in the spaced condition, as previously reported by Blaisdell et al. (2003). We found that extinction of the context when training was massed (massed CtxE group) resulted in less suppression to the target stimulus compared with the massed NoE group, which suggests that massed training made the context a viable comparator to X, and allowed it to compete with CS A in modulating behavioral control by X. This suggests that the associative status of the context influenced behavioral control of X at test rather than during Phase 2. Additionally, we found no difference in responding between the spaced NoE and spaced CtxE groups, which is consistent with the ECH prediction that, given spaced trials, the context should not be an effective comparator stimulus. These results support the predictions made by the ECH. Despite one of the comparisons lacking the desired statistical significance, the overall pattern of the results is more consistent with the ECH than any other model we entertained.

General Discussion

The present experiments were designed to examine the interaction of overexpectation and trial massing. In Experiment 1, we looked at the basic effects of trial massing and overexpectation in first-order conditioning and assessed the prediction made by the ECH that combining these two detrimental treatments would result in more stimulus control of behavior than either treatment alone. The overexpectation effect was found, as well as a reliable trial spacing effect. More important, we observed a counteraction between these two treatments (i.e., a tendency toward alleviation, rather than summation, of the decrement in responding observed relative to either the overexpectation effect or the trial spacing effect alone when the two treatments are administered together). The massed AX presentations in Phase 2 presumably established strong context–A [Link 2.3] and context–US [Link 3.3] associations (to the extent that these associations were not already formed in Phase 1) that, according to the ECH, are essential for the observed counteraction effect. In preparation for Experiment 3, Experiment 2 replicated Experiment 1 within a sensory preconditioning situation. In Experiment 3, the primary comparator stimuli (i.e., A and the training context) were extinguished in separate groups to test further predictions made by the ECH (Denniston et al., 2001) that doing so should enable the other comparator stimulus to compete with X, thereby reverting the counteraction. The overall pattern of results obtained was consistent with the ECH.

Most contemporary models of learning can account for the trial spacing effect and the overexpectation effect; however, the ECH is the only one that predicts the counteraction of the two. Additionally, the ECH makes unique predictions, as confirmed in Experiment 3, concerning extinction of A or the context after Phase 2 training. Notably, Van Hamme and Wasserman's (1994) revised Rescorla–Wagner model makes some of the same predictions as the ECH regarding retrospective revaluation, even though it does not anticipate the counteraction of overexpectation and trial massing. According to this model, absent stimuli associated with cues that are present are assumed to have negative associability (in the original Rescorla–Wagner model, absent stimuli had an associability of zero). Thus, during extinction of A after AX–US spaced training trials, X presumably had a negative associability, which on A- alone (extinction) trials led to increases in the strength of the X–US association. Thus, this model anticipates that posttraining extinction of A after spaced overexpectation treatment should decrease the response deficit caused by overexpectation treatment (i.e., increase behavioral control by X). This is consistent with the decrease in response deficit that we observed with extinction of A (and suggested with extinction of the context) in the spaced condition of Experiment 3. Likewise, during extinction of A after massed AX–US training, X again should have had a negative associability that leads to the same predictions as with spaced trials, in contradiction with our observations. When the context is extinguished after massed AX–US trials, responding should increase because of X's negative associability and an unfulfilled expectation of the US, according to Van Hamme and Wasserman; this is consistent with the response pattern that we observed after spaced AX–US trials but not massed AX–US trials. In fact, a strong effect in the opposite direction was seen. In summary, Van Hamme and Wasserman anticipated only two of the four retrospective revaluation effects that were observed (or at least suggested) in Experiment 3. In the two cases in which their model fails to anticipate the data, the model's predictions are diametrically opposed to what was observed.

Like the Rescorla–Wagner model (Rescorla & Wagner, 1972), Wagner's (1981) SOP can account for both the overexpectation effect and the trial spacing effect. However, it cannot account for the counteraction observed in these experiments. Instead, the SOP predicts summation of these two detrimental treatments. Additionally, Wagner's SOP cannot account for the retrospective revaluation effects observed in Experiment 3.

Dickinson and Burke (1996) proposed a revised version of Wagner's SOP (MSOP) that can account for some retrospective revaluation effects. Through a different mechanism, the MSOP makes the same ordinal predictions as the revised Rescorla–Wagner model. That is, the MSOP predicts that, when A or the context is extinguished after spaced AX-US training, the behavioral result should be an increase in conditioned responding to X compared with a group that received no extinction but identical training. This increase in behavioral control is consistent with our observations. However, the MSOP, also like the revised Rescorla–Wagner model, does not make predictions consistent with our observations in the massed AE or massed CtxE groups of Experiment 3.

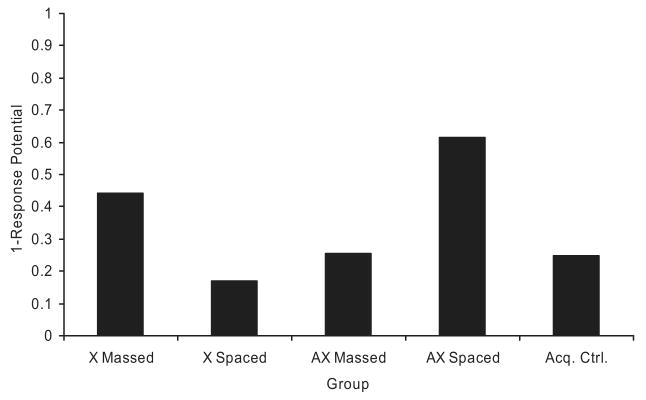

Predictions of responding according to the ECH were made using the recent mathematical implementation of the ECH, sometimes-competing retrieval (SOCR; Stout & Miller, 2007). Like ECH, SOCR assumes that contiguity is necessary and sufficient for learning to occur. It uses an individual stimulus error-correcting rule, similar to that of Bush and Mosteller (1955), to modify associative strength. Figure 5 depicts the results of a SOCR simulation of Experiment 1. All of the parameters used were the same as those used by Stout and Miller, and the numbers of trials were the same as those used in Experiment 1. The predictions of ordinal change with the added cue (AX) in the massed and spaced conditions are supported by the data. However, SOCR predicts that suppression in the X massed group should be stronger than that for the AX Spaced group, whereas the data show similarly low levels of suppression. Additionally, SOCR predicts that suppression levels should be equal in the AX massed and Acq. Ctrl. groups, whereas the data show that suppression is actually stronger in the Acq. Ctrl. group.

Figure 5.

Sometimes-competing retrieval (SOCR; Stout & Miller, 2007) simulation of Experiment 1. Note that the vertical axis represents 1 – response potential (i.e., lower numbers indicate more behavioral control). Acq. Ctrl. = acquisition control.

Experiments 2 and 3 used sensory preconditioning preparations. SOCR is able to account for basic sensory preconditioning as a result of its so-called switching operator, by which comparator stimuli initially additively transfer their association to the US to the direct target–US association (i.e., Link 1, which is null in the case of sensory preconditioning). Then, over trials that include experience with the target indirectly activating a representation of the outcome, the transfer progressively becomes more subtractive. Hence, the switching operator determines whether the comparator term is facilitative or competitive. It is important that each comparator process has its own switching operator, which is how the model can concurrently predict sensory preconditioning as well as counteraction effects. In the case of sensory preconditioning, the two types of trials are phasically segregated with all of the cue–outcome trials preceding the outcome–US trials. Therefore, the target stimulus and the US are never directly paired, which prevents the target stimulus from either directly or indirectly activating a US representation until the first test trial. As the target stimulus and the US were never directly paired, at test the first-order switching operator is assumed to be facilitative (thus allowing X to exhibit excitatory behavioral control) and change over to competitive slowly across successive test trials. According to the model, responding to the target stimulus at test is proportional to the product of Links 2 and 3. Phase 2 trial massing allows the context to serve as a comparator stimulus for the X–S association (i.e., a second-order comparator stimulus for the X–US association), and the presence of A allows it to serve as a second-order comparator stimulus for the X–US association as well. Moreover, the massing of AX trials in the compound condition creates a strong A–context association that makes A and the context comparator stimuli for each other in their potential to activate a representation of S, resulting in a counteraction effect between overexpectation treatment and trial massing. Additionally, subsequent extinction of either A or the context should allow the context or A, respectively, to attenuate responding to X. According to the ECH, in Experiment 3, when A was extinguished for the massed AE group, the context remained the only effective comparator stimulus for X; thus, it was able to exert its full response-degrading potential. Similarly, extinguishing the context for the massed CtxE group resulted in A being freed to depress behavioral control by X. However, in the spaced condition, the context was assumed not to have become a strong comparator for X. Consequently, extinguishing A for the spaced AE group resulted in increased behavioral control by X, because it no longer had any effective comparator stimulus. In contrast, extinguishing the context for the spaced CtxE group was not expected to affect behavioral control by X, because the context never became an effective comparator stimulus in the first place. A would still be expected to compete with X; thus, behavioral control by X should be weak. Thus, the model clearly anticipated the counteraction effect and the four retrospective revaluation effects of Experiment 3.

Of note, there has recently been a debate regarding the effect of posttraining extinction of a companion cue after cue competition treatment (Holland, 1999; Kaufman & Bolles, 1981; Liljeholm & Balleine, 2006; Shevill & Hall, 2004). Whereas, in some studies, decreases in behavioral control by a target cue after extinction of the companion cue have been observed (viz., mediated extinction; Holland, 1999, Experiment 3; Shevill & Hall, 2004, Experiment 1C), other studies have found increases in behavioral control (Liljeholm & Balleine, 2006; Shevill & Hall, 2004, Experiment 2). Moreover, some experiments have found no change (Holland, 1999, Experiment 1). These discrepancies are noteworthy, not only because of disagreements at the empirical level, but also because some models anticipate no change (Rescorla & Wagner, 1972; Wagner, 1981) some anticipate an increase in behavioral control (Dickinson & Burke, 1996; Van Hamme & Wasserman, 1994), but none of these models anticipate both, which is what we observed in Experiment 3 after extinction of the companion cue A. Thus, ECH is unusual in that it anticipates both retrospective revaluation and mediated extinction. Moreover, ECH suggests that the level of cue competition observed during training predicts the effect of posttraining manipulations. In the present experiments, when overexpectation training was administered with spaced training trials, an increase in behavioral control was observed after extinction of A. Conversely, when overexpectation training was conducted with massed trials (which results in little overexpectation effect or even a counteraction) a decrease in behavioral control was observed after extinction of A.

The present experiments exemplify the necessity for learning models to acknowledge that animals learn about all stimuli that are present during training and that these associations interact at test to influence performance. This work adds to the growing literature demonstrating that multiple stimulus competition effects can interact in a nonsummative manner (i.e., counteraction effects). Furthermore, the present counteraction effect did not use overshadowing as one of the debilitating treatments in contrast to most previous counteraction experiments (Blaisdell et al., 1998; Stout, Chang, & Miller, 2003; Stout, Arcediano, Escobar, & Miller, 2003; Urushihara & Miller, 2006, 2007). Here we have demonstrated that overshadowing need not be one of the conjoined debilitating treatments to obtain a counteraction effect. In summary, the present data emphasize the importance of information processing that seemingly occurs at the time of test.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant 33881 from the National Institute for Mental Health. We thank Eric Curtis, Sean Gannon, Ryan Green, Jeremie Jozefowiez, Mario Laborda, Bridget McConnell, Mikael Molet, Lisa Ng, Gonzalo P. Urcelay, and Jim Witnauer for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

References

- Annau Z, Kamin LT. The conditioned emotional response as a function of intensity of the US. Journal of Comparative and Physiological Psychology. 1961;51:128–132. doi: 10.1037/h0042199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barela PB. Theoretical mechanisms underlying the trial-spacing effect in Pavlovian fear conditioning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1999;25:177–193. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.25.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaisdell AP, Bristol AS, Gunther LM, Miller RR. Overshadowing and latent inhibition counteract each other: Support for the comparator hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 1998;24:335–351. doi: 10.1037//0097-7403.24.3.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaisdell AP, Denniston JC, Miller RR. Recovery from the overexpectation effect: Contrasting performance-focused and acquisition-focused models of retrospective revaluation. Animal Learning & Behavior. 2003;29:367–380. [Google Scholar]

- Brogden WJ. Sensory pre-conditioning. Journal of Experimental of Psychology. 1939;25:323–332. doi: 10.1037/h0058465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush RR, Mosteller F. Stochastic models for learning. New York: Wiley; 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Denniston JC, Miller RR, Matute H. Biological significance as a determinant of cue competition. Psychological Science. 1996;7:325–331. [Google Scholar]

- Denniston JC, Savastano HI, Miller RR. The extended comparator hypothesis: Learning by contiguity, responding by relative strength. In: Mowrer RR, Klein SB, editors. Handbook of contemporary learning theories. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 2001. pp. 65–117. [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson A, Burke J. Within-compound associations mediate the retrospective revaluation of causality judgments. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1996;49B:60–80. doi: 10.1080/713932614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland PC. Overshadowing and blocking as acquisition deficits: No recovery after extinction of overshadowing or blocking cues. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1999;52B:307–333. doi: 10.1080/027249999393022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman MA, Bolles RC. A nonassociative aspect of overshadowing. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 1981;18:318–320. [Google Scholar]

- Liljeholm M, Balleine BW. Stimulus salience and retrospective revaluation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2006;32:481–487. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.32.4.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RR, Matute H. Biological significance in forward and backward blocking: Resolution of a discrepancy between animal conditioning and human causal judgment. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1996;25:370–386. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.125.4.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JL, Well AD. Research design and statistical analysis. 2nd. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Oberling P, Bristol AS, Matute H, Miller RR. Biological significance attenuates overshadowing, relative validity, and degraded contingency effects. Animal Learning & Behavior. 2000;28:172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA. Reduction in the effectiveness of reinforcement after prior excitatory conditioning. Learning and Motivation. 1970;1:372–381. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA, Wagner AR. A theory of Pavlovian conditioning: Variations in the effectiveness of reinforcement and non-reinforcement. In: Black AH, Prokasy WF, editors. Classical conditioning II: Current research and theory. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1972. pp. 64–99. [Google Scholar]

- Shevill I, Hall G. Retrospective revaluation effects in the conditioned suppression procedure. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2004;57B:331–347. doi: 10.1080/02724990344000178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sissons HT, Urcelay GP, Miller RR. Overshadowing and CS duration: Counteraction and a reexamination of the role of within-compound associations in cue competition. 2008 doi: 10.3758/LB.37.3.254. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout S, Arcediano F, Escobar M, Miller RR. Overshadowing as a function of trial number: Dynamics of first- and second-order comparator effects. Learning & Behavior. 2003;31:85–97. doi: 10.3758/bf03195972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout SC, Chang R, Miller RR. Trial spacing is a determinant of cue interaction. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2003;29:23–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout SC, Miller RR. Sometimes-competing retrieval (SOCR): A formalization of the comparator hypothesis. Psychological Review. 2007;114:759–783. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.3.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urcelay GP, Miller RR. Counteraction between overshadowing and degraded contingency treatments: Support for the extended comparator hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2006;32:21–32. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.32.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urushihara K, Miller RR. Overshadowing and the outcome alone exposure effect counteract each other. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2006;32:253–270. doi: 10.1037/0097-7403.32.3.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urushihara K, Miller RR. CS-duration and partial-reinforcement effects counteract overshadowing in select situations. Learning & Behavior. 2007;35:201–213. doi: 10.3758/bf03206426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urushihara K, Stout SC, Miller RR. The basic laws of conditioning differ between elemental cues and cues trained in compound. Psychological Science. 2004;14:268–271. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hamme LJ, Wasserman EA. Cue competition in causality judgments: The role of nonpresentation of compound stimulus elements. Learning and Motivation. 1994;25:127–151. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner AR. SOP: A model of automatic memory processing in animal behavior. In: Spear NE, Miller RR, editors. Information processing in animals: Memory mechanisms. Hillsdale, N J: Erlbaum; 1981. pp. 5–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DS, Miller RR. Determinants of cue interactions. Behavioral Processes. 2008;78:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witnauer JE, Urcelay GP, Miller RR. Reduced blocking as a result of increasing the number of blocking cues. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review. 2008;15:651–655. doi: 10.3758/pbr.15.3.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]