Abstract

Earlier iterations of the ‘hygiene hypothesis’, in which infections during childhood protect against allergic disease by stimulation of the T helper type 2 (Th2)-antagonistic Th1 immunity, have been supplanted progressively by a broader understanding of the complexities of the underlying cellular and molecular interactions. Most notably, it is now clear that whole certain types of microbial exposure, in particular from normal gastrointestinal flora, may provide key signals driving postnatal development of immune competence, including mechanisms responsible for natural resistance to allergic sensitization. Other types of infections can exert converse effects and promote allergic disease. We review below recent findings relating to both sides of this complex picture.

Keywords: allergy, asthma, childhood, infancy, respiratory infections

Introduction

Until the late 1980s, interest in the role of infections in allergic diseases focused principally upon the process of primary allergic sensitization. The relevant experimental literature of the time contained a range of observations which argued for a stimulatory role for infections, including the capacity of bacterial-derived immunostimulants such as pertussigen to selectively enhance priming for immunoglobulin (Ig)E antibody production [1], and the potential of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to bypass or break tolerance to mucosally applied antigens/allergens. Additionally, several independent laboratories reported that respiratory viral infections such as influenza could subvert the generation of protective ‘inhalation tolerance’ to aeroallergens (for example) [2,3], a process described originally by our laboratory as the respiratory tract equivalent of oral tolerance (reviewed in [4]). More recently, signals such as enterotoxins from skin-dwelling bacteria have been invoked as important contributors to the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis [5].

However, it was also clear from other observations that microbial exposure per se could not be considered in generic terms as ‘pro-atopic’. For example, other microbial-derived agents exemplified by the components of Freund's adjuvant displayed atopy-antagonistic activity [6], and stimuli derived from normal gut flora were demonstrated to be necessary to facilitate the expression of oral tolerance to fed allergen [7,8], and also inhalation tolerance to aeroallergen [4]. These observations suggested that microbial-derived stimuli had potential to modulate the aetiology and pathogenesis of atopic diseases in dichotomous ways, their ultimate effects perhaps being context-dependent.

A limitation of these ideas was their universal derivation from experimental models, leaving open the question of applicability to corresponding human disease. In order to bridge this conceptual gap, some creative epidemiology was required.

Epidemiological studies on the aetiology of human allergic disease and the arrival of the ‘hygiene hypothesis’

While it was not the first observation noting the inverse relationship between risk for allergic disease in humans and microbial exposure/infection frequency, the insightful publication by Richard Strachan in 1989 [9] first articulated this concept in a way that caught the attention of the immunology community, who were focusing upon underlying sensitization mechanisms. The core observations in the initial Strachan study and subsequent follow-ups pointed to a series of related factors, notably family size, socio-economic class and birth order, as important determinants of allergy risk in the United Kingdom. In particular, the lowest risk was seen in children with multiple older siblings, from relatively poor families [9,10]. These ‘low-risk’ children grew up typically experiencing a relatively high frequency of gastric and respiratory infections contracted from their older siblings, and the concept developed that these robust early microbial exposures helped to educate the immune system in some way to the dangers of inappropriate immune responses against non-pathogenic antigens. These ideas were strengthened by observations from our group and others, which identified early postnatal life as the period of maximal risk for primary allergic sensitization, and moreover identified delayed postnatal maturation of T helper (Th) cell function (in particular Th1 function) as a key component of genetic risk for atopy [11–14]. The concept that microbial exposure, particularly to gastrointestinal flora, is a key element in promoting normal postnatal maturation of immune competence has been well established in the literature for many years, in particular relating to the rebalancing of Th1/Th2 immunity to redress the Th2 imbalance that is a feature of healthy immune function in the fetus [15]. However, it has become increasingly clear that Th cell function represents only the ‘tip of the iceberg’ in this context, and that immune mechanisms across the full spectrum of innate, adaptive T effector and T regulatory functions are variably compromised in early life [16–19].

Moreover, this general principle that immune function undergoes major maturational changes during the early postnatal period has implications beyond allergic disease pathogenesis. The most obvious example involves responses to vaccines administered during early infancy. This issue is discussed in more detail in another section of the workshop [20], but briefly, the intrinsic Th2 polarity of the infant immune system sets the stage for equivalently polarized initial T cell responses to vaccines, at least to those such as DtaP (diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis), which lack any Toll-like receptor (TLR)-stimulatory components [21]. This is not seen with vaccines such as bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG), which contain strong Th1-stimulatory components [22], and indeed the inclusion of a single dose of the DTwP vaccine in the initial three-dose priming schedule appears enough to ‘balance’ the ensuing Th memory response [23]. Of note, this tendency towards excessive Th2 polarity in memory responses to DTaP is strongest among children with a positive family history of atopy (AFH+) in whom Th1 function is most attenuated during infancy, and who represent the high-risk group with respect to subsequent development of allergy and asthma.

Additionally, slow postnatal development of Th1 function is associated with increased risk for early respiratory infection with viruses such as respiratory syncitial virus (RSV), as demonstrated in independent cohort studies in Australia [21] and the United States [24].

The notion that microbial exposure during early life might drive the postnatal maturation of immune competence and hence protect against atopy has been discussed widely over the last 15 years, and is supported in principle by a wide body of experimental animal data [25]. In particular, the role of the commensal flora in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) appears to be of paramount importance [26], and it is generally accepted that signals from these organisms mediate the progressive transition from the fetal (Th2 polarized) to the more balanced immunophenotype observed in healthy children beyond infancy. Direct data in humans concerning the role of GIT flora in this context are understandably very difficult to obtain, but nevertheless studies focusing upon stool samples from infants who do/do not develop atopy have provided significant preliminary findings in this direction [27]. One of the factors limiting progress in this area is the inherent complexity of the flora, but the advent of genomics-based approaches is rapidly plugging this technology gap and the increasing application of this technology will hopefully clarify the role of the flora to a significant degree in the near future.

More indirect human data are available from the relevant epidemiology literature concerning the role of microbial pathogens as opposed to commensal flora [28,29]. The original conceptualization of the hygiene hypothesis envisaged infection frequency as the key factor discriminating high-risk and low-risk populations, but it has become evident that qualitative aspects of infection(s) may be of equivalent or even greater importance. In particular, there is strong evidence linking enteric infections with reduced risk for allergic sensitization [30], and similarly for mild–moderate respiratory infections (without wheeze/fever) which spread to the lower respiratory tract [31], whereas upper respiratory tract infections do not appear to play such a role [32].

Viral infections: a double-edged sword?

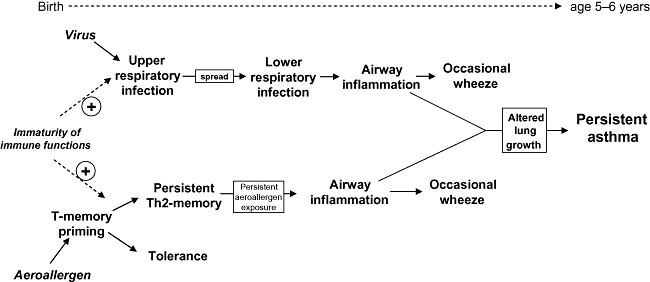

In contrast to the above, one class of viral infections has been linked epidemiologically in multiple studies to risk for subsequent development of asthma in childhood, notably moderate–severe viral infections which spread to the lower respiratory tract and which are of sufficient intensity to trigger wheeze and/or febrile responses [32–34]. These infections serve as independent risk factors for subsequent asthma development, but their asthma-promoting effects are much stronger against a background or respiratory allergy (reviewed in [35,36]). On the basis of these findings, we have proposed a ‘two-hit’ model for asthma aetiology in early childhood (Fig. 1) in which interactions between inflammatory pathways involved in host responses to aeroallergens and viruses infecting the airway epithelium synergize to perturb early postnatal lung growth and differentiation, resulting in later expression of the asthma phenotype [35,36]. These interactions are most profound in children who are sensitized to aeroallergens early and who experience severe infections during the same period [32].

Fig. 1.

Risk for virus infections that spread from the upper to the lower respiratory tract, and for sensitization to aeroallergens, is maximal in the first few years of life, due mainly to maturational deficiencies in innate and adaptive immune functions during this life phase. Microbial exposure (particularly via the gut) can, on one hand, protect against both processes via promoting functional maturation of immune competence, but in other circumstances (exemplified by severe respiratory viral infections) can interact synergistically with underlying atopic inflammation to promote development of clinically relevant allergic disease.

A key question remaining to be resolved fully relates to the nature of these interactions between the anti-viral and atopic pathways. We hypothesize that one important focus of these interactions is the network of airway mucosal dendritic cells (AMDC) first described in humans [37] and experimental animals [38,39] by our group, and which are now recognized generally to play an essential ‘gatekeeper’ role in control of immune responses in the respiratory tract to all classes of inhaled antigens and pathogens [40,41]. At birth, this network in rodents is poorly developed [42], and local expression of adaptive immunity in airway tissues is thus constrained severely by the limited local availability of APCs; a similar situation has been reported in airway tissues of human infants [43]. In the rodent this DC network develops fastest in the nasal turbinates, which represent the collection point for the bulk of inspired particulate antigen, including microbial agents [42]. This suggests that postnatal maturation of the airway DC network may be driven by stimulation from environmental irritants, including those associated with microbial pathogens, and data from infants who succumb to infections which demonstrate markedly increased AMDC density in the airway mucosa [43] are consistent with this possibility. Moreover, kinetic studies in a rat model of respiratory parainfluenza infection, which demonstrate rapid expansion of the AMDC network during early infection [44], provide further support for this idea, and similar findings are available for inhalation of bacterial stimuli [45]. Intriguingly, in the case of viral infection, the AMDC network does not return to baseline for several weeks post pathogen clearance [44], suggesting long-term effects of viral infection (related possibly to covert persistence of low levels of virus) on homeostasis of this DC population. These findings have prompted us to add a specific AMDC component to the ‘two-hit’ model for asthma development [36]. In particular, we point to the possibility that viral infection may enhance the pathogenicity of nascent aeroallergen-specific Th2 immunity in the airway mucosa of recently sensitized children by expanding the population of available APCs which are necessary for local T memory cell activation [36].

Maintenance of ongoing expression of the atopic asthmatic phenotype in school-age children: a covert role for viruses in triggering severe asthma exacerbations

It is generally assumed that the triggering of wheezing attacks in humans sensitized to perennial ‘indoor’ allergens occurs directly via inhalation of supra-threshold levels of the relevant allergens. This can undoubtedly occur, and the phenomenon can be reproduced readily in murine models; however, it is by no means the only route via which asthma attacks can be triggered in atopics. This is particularly the case with respect to asthma exacerbations of sufficient severity to require hospitalization, which appear to be triggered instead by lower respiratory tract viral infection (reviewed in [36]). Our recent studies have identified a pathway by which host–anti-viral immunity can recruit allergen-specific Th2 recall responses into the inflammatory response at the airway mucosal infection site. The key element in this process is up-regulation of IgE-FcR expression on the myeloid precursors of AMDC, thus arming these cells optimally for subsequent presentation of activating signals to Th2 memory cells [46]. The resulting Th2 milieu in the airway mucosa is likely to blunt Th1 polarized anti-viral defences, and as such may represent an example of successful viral invasion of sterilizing immunity. However, in highly atopic individuals this mechanism appears to ‘overshoot’ and the severity of resulting Th2-mediated inflammation can pose a threat to host survival considerably in excess of the virus itself [46].

The ‘elephant in the room’: regulatory T cells (Tregs), GIT flora and regulation of airway inflammation

The link between Tregs and the ‘hygiene hypothesis’ is discussed in detail elsewhere in this workshop. In principle, stimulation of the T cell system via microbial-derived signals emanating principally from the GIT may be one route via which functionally mature Tregs are generated, and these cells may contribute to maintenance of homeostasis in peripheral tissues distal to the GIT. In early life, one source of such Tregs may be recent thymic emigrant (RTE) CD4+ T cells. Human in vitro studies from our group and others [16,45,47], echoing earlier work in the mouse [48], have demonstrated that naive RTE which dominate the circulating CD4+ T cell compartment during infancy respond ‘non-specifically’ to peptides, leading to rapid activation and cytokine production which is usually terminated soon thereafter by apoptotic death. However, a subset of these RTE survive and potentially may thus enter the recirculating T cell compartment [16,47]. These survivors acquire Treg activity during the activation process [16]; this process may reflect events occurring in the lymphoid drainage of the GIT under the influence of microbial-derived antigens, providing a continuous ‘drip-feed’ of functionally activated Tregs.

The de novo generation and/or boosting of existing Treg activity by controlled microbial stimulation of the GIT is one of the aims of probiotic therapies which are being tested in many centres internationally, but there are few direct data available to confirm the efficient operation of this mechanism in humans. However, recent mouse data support the potential feasibility of this approach. In particular, gavage of mice with a bolus of live Lactobacillus reuteri increases numbers and functional activity of Tregs in central lymphoid organs [49]. Moreover, if this is carried out in sensitized animals prior to aeroallergen challenge, ensuing lung eosinophilia and airways hyperresponsiveness is attenuated significantly and this effect can be reproduced by adoptive transfer of Tregs harvested from spleens of L. reuteri-gavaged animals [49]. We have obtained similar findings in a rat atopic asthma model employing repeated feeding with a microbial extract containing multiple TLR ligands, and moreover we have observed that the attenuation of aeroallergen-induced airways inflammatory responses in prefed animals is associated with increased baseline numbers of Tregs in the airway mucosa (to be published). These latter findings suggest that one of the principle tenets of the ‘common mucosal immune system’ concept, notably that adaptive immune cell populations activated in the GIT mucosa will subsequently traffic preferentially to other mucosal sites, may be exploitable in relation to therapeutic control of allergy-induced lung inflammation. They also provide a possible explanation for earlier epidemiological findings linking certain enteric infections with resistance to allergic disease [30].

Conclusions

The emerging literature in several areas points to complex interactions between exposure to microbial pathogens and susceptibility to the induction and expression of allergic diseases exemplified by atopic asthma. Earlier notions that infections protect against allergy by enhancing Th1-associated immunity have been supplanted by a broader understanding of the relevance of issues, such as timing, type and intensity of infections, to the underlying disease process. Many issues remain to be resolved, and this will remain a ‘hot topic’ in the allergy field for some time to come.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Munoz JJ, Peacock MG. Action of pertussigen (pertussis toxin) on serum IgE and Fcε receptors on lymphocytes. Cell Immunol. 1990;127:327–36. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(90)90136-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakamoto M, Ida S, Takishima T. Effect of influenza virus infection on allergic sensitization to aerosolized ovalbumin in mice. J Immunol. 1984;132:2614–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holt PG, Vines J, Bilyk N. Effect of influenza virus infection on allergic sensitization to inhaled antigen in mice. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1988;86:121–3. doi: 10.1159/000234617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holt PG, Sedgwick JD. Suppression of IgE responses following antigen inhalation: a natural homeostatic mechanism which limits sensitization to aeroallergens. Immunol Today. 1987;8:14–5. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(87)90825-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sicherer SH, Leung DYM. Advances in allergic skin disease, anaphylaxis, and hypersensitivity reactions to foods, drugs, and insects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:153–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ishizaka K. Regulation of IgE synthesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 1984;2:159–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.02.040184.001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wannemuehler MJ, Kiyono H, Babb JL, et al. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) regulation of the immune response: LPS converts germfree mice to sensitivity to oral tolerance induction. J Immunol. 1982;129:959–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sudo N, Sawamura S-A, Tanaka K, et al. The requirement of intestinal bacterial flora for the development of an IgE production system fully susceptible to oral tolerance induction. J Immunol. 1997;159:1739–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ. 1989;299:1259–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strachan DP. Family size, infection and atopy: the first decade of the hygiene hypothesis. Thorax. 2000;55(Suppl. 1):S2–S10. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.suppl_1.s2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holt PG, Clough JB, Holt BJ, et al. Genetic ‘risk’ for atopy is associated with delayed postnatal maturation of T-cell competence. Clin Exp Allergy. 1992;22:1093–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1992.tb00135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holt PG, O'Keeffe PO, Holt BJ, et al. T-cell ‘priming’ against environmental allergens in human neonates: sequential deletion of food antigen specificities during infancy with concomitant expansion of responses to ubiquitous inhalant allergens. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1995;6:85–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1995.tb00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prescott SL, Macaubas C, Smallacombe T, et al. Development of allergen-specific T-cell memory in atopic and normal children. Lancet. 1999;353:196–200. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)05104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang M, Kemp A, Varigos G. Interleukin-4 and interferon-gamma production in children with atopic disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1993;92:120–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb05957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wegmann TG, Lin H, Guilbert L, et al. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal–fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a Th2 phenomenon? Immunol Today. 1993;14:353–56. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90235-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thornton CA, Upham JW, Wikström ME, et al. Functional maturation of CD4+ CD25+ CTLA4+ CD45RA+ T regulatory cells in human neonatal T cell responses to environmental allergens. J Immunol. 2004;173:3084–92. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy O. Innate immunity of the newborn: basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:379–90. doi: 10.1038/nri2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yerkovich ST, Wikstrom ME, Suriyaarachchi D, et al. Postnatal development of monocyte cytokine responses to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Pediatr Res. 2007;62:547–52. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181568105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegrist CA. Vaccination in the neonatal period and early infancy. Int Rev Immunol. 2000;19:195–219. doi: 10.3109/08830180009088505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Biggelaar AHJ, Holt PG. 99th Dahlem Conference on Infection, Inflammation and Chronic Inflammatory Disorders: Neonatal immune function and vaccine responses in children born in low-income versus high-income countries. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:42–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04137.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rowe J, Macaubas C, Monger T, et al. Heterogeneity in diphtheria–tetanus–acellular pertussis vaccine-specific cellular immunity during infancy: relationship to variations in the kinetics of postnatal maturation of systemic Th1 function. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:80–8. doi: 10.1086/320996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchant A, Goetghebuer T, Ota M, et al. Newborns develop a Th1-type immune response to Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccination. J Immunol. 1999;163:2249–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowe J, Yerkovich ST, Richmond P, et al. Th2-associated local reactions to the acellular diphtheria tetanus pertussis vaccine in 4- to 6-year-old children. Infect Immun. 2005;73:8130–5. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8130-8135.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Copenhaver CC, Gern JE, Li Z, et al. Cytokine response patterns, exposure to viruses, and respiratory infections in the first year of life. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:175–80. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200312-1647OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okada H, Kuhn CH, Feillet H, Bach J-F. The ‘hygiene hypothesis’ for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holt PG. Environmental factors and primary T-cell sensitization to inhalant allergens in infancy: reappraisal of the role of infections and air pollution (Review) Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1995;6:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1995.tb00250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Björkstén B, Naaber P, Sepp E, et al. The intestinal microflora in allergic Estonian and Swedish 2-year old children. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29:342–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ercolini AM, Miller SD. The role of infections in autoimmune disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;155:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bach JF. The effect of infections on susceptibility to autoimmune and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:911–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matricardi PM, Rosmini F, Riondino S, et al. Exposure of foodborne and orofecal microbes versus airborne viruses in relation to atopy and allergic asthma: epidemiological study. BMJ. 2000;320:412–17. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7232.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez FD, Stern DA, Wright AL, et al. Association of non-wheezing lower respiratory tract illnesses in early life with persistently diminished serum IgE levels. Thorax. 1995;50:1067–72. doi: 10.1136/thx.50.10.1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kusel MMH, de Klerk NH, Kebadze T, et al. Early-life respiratory viral infections, atopic sensitization and risk of subsequent development of persistent asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:1105–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martinez FD, Wright AL, Taussig LM, et al. Asthma and wheezing in the first six years of life. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:133–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oddy WH, de Klerk NH, Sly PD, et al. The effects of respiratory infections, atopy, and breastfeeding on childhood asthma. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:899–905. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00103602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holt PG, Upham JW, Sly PD. Contemporaneous maturation of immunological and respiratory functions during early childhood: implications for development of asthma prevention strategies. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116:16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sly PD, Boner AL, Björksten B, et al. Early identification of atopy in the prediction of persistent asthma in children. Lancet. 2008;372:1100–16. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61451-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holt PG, Schon-Hegrad MA, Phillips MJ, et al. Ia-positive dendritic cells form a tightly meshed network within the human airway epithelium. Clin Exp Allergy. 1989;19:597–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1989.tb02752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holt PG, Schon-Hegrad MA, Oliver J, et al. A contiguous network of dendritic antigen-presenting cells within the respiratory epithelium. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1990;91:155–9. doi: 10.1159/000235107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schon-Hegrad MA, Oliver J, McMenamin PG, et al. Studies on the density, distribution, and surface phenotype of intraepithelial class II major histocompatibility complex antigen (Ia)-bearing dendritic cells (DC) in the conducting airways. J Exp Med. 1991;173:1345–56. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holt PG, Strickland DH, Wikstrom ME, et al. Regulation of immunological homeostasis in the respiratory tract. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:142–52. doi: 10.1038/nri2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lambrecht BN, Prins J-B, Hoogsteden HC. Lung dendritic cells and host immunity to infection. Eur Respir J. 2001;18:692–704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nelson DJ, McMenamin C, McWilliam AS, et al. Development of the airway intraepithelial dendritic cell network in the rat from class II MHC (Ia) negative precursors: differential regulation of Ia expression at different levels of the respiratory tract. J Exp Med. 1994;179:203–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tschernig T, Debertin AS, Paulsen F, et al. Dendritic cells in the mucosa of the human trachea are not regularly found in the first year of life. Thorax. 2001;56:427–31. doi: 10.1136/thorax.56.6.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McWilliam AS, Marsh AM, Holt PG. Inflammatory infiltration of the upper airway epithelium during Sendai virus infection: involvement of epithelial dendritic cells. J Virol. 1997;71:226–36. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.226-236.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reen DJ. Activation and functional capacity of human neonatal CD4 T cells. Vaccine. 1998;16:1401–8. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Subrata LS, Bizzintino J, Tulic MK, et al. Interactions between innate and atopic immunoinflammatory pathways precipitate and sustain asthma exacerbations in children. J Immunol. 2009;183:2793–800. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hassan J, Reen DJ. Human recent thymic emigrants – identification, expansion, and survival characteristics. J Immunol. 2001;167:1970–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gavin MA, Bevan MJ. Increased peptide promiscuity provides a rationale for the lack of N regions in the neonatal T cell repertoire. Immunity. 1995;3:793–800. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90068-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karimi K, Inman MD, Bienenstock J, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri-induced regulatory T cells protect against an allergic airway response in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:186–93. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200806-951OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]