Abstract

Initiation of DNA replication in eukaryotic cells is controlled through an ordered assembly of protein complexes at replication origins. The molecules involved in this process are well conserved but diversely regulated. Typically, initiation of DNA replication is regulated in response to developmental events in multicellular organisms. Here, we elucidate the regulation of the first S phase of the embryonic cell cycle after fertilization. Unless fertilization occurs, the Mos-MAPK-p90Rsk pathway causes the G1-phase arrest after completion of meiosis in starfish eggs. Fertilization shuts down this pathway, leading to the first S phase with no requirement of new protein synthesis. However, how and in which stage the initiation complex for DNA replication is arrested by p90Rsk remains unclear. We find that in G1-arrested eggs, chromatin is loaded with the Mcm complex to form the prereplicative complex (pre-RC). Inactivation of p90Rsk is necessary and sufficient for further loading of Cdc45 onto chromatin to form the preinitiation complex (pre-IC) and the subsequent initiation of DNA replication. However, cyclin A-, B-, and E-Cdk's activity and Cdc7 accumulation are dispensable for these processes. These observations define the stage of G1 arrest in unfertilized eggs at transition point from pre-RC to pre-IC, and reveal a unique role of p90Rsk for a negative regulator of this transition. Thus, initiation of DNA replication in the meiosis-to-mitosis transition is regulated at the pre-RC stage as like in the G1 checkpoint, but in a manner different from the checkpoint.

Keywords: Cdc45, G1 arrest, Mcm complex, Mos-MAPK pathway, oocyte-to-embryo transition

DNA replication in eukaryotic cells is initiated through an ordered assembly of protein complexes at replication origins (1, 2). Replication origins are first recognized and bound by the origin recognition complex (ORC). During late M or early G1 phase, Cdc6 associates onto ORC-containing DNA. Then, MCM (minichromosome maintenance) proteins associate with the ORC- and Cdc6-containing replication origins, requiring Cdt1 to form a prereplicative complex (pre-RC). At the onset of S phase, Cdc45 associates with the pre-RC to form a preinitiation complex (pre-IC) that is capable of origin unwinding and of promoting assembly of replication forks at replication origin. Thus, Cdc45 plays a crucial role in activation of replication origins.

Although the mechanism of initiation of DNA replication is well conserved, its control is diverse (3). In addition to evolutionary variation, DNA replication is regulated in response to developmental events in multicellular organisms. Fertilization is the first major event in development and is necessary for both releasing meiotic arrest and restarting the cell cycle with initiation of the first round of DNA replication. In some organisms, including Drosophila and echinoderms (4–6), fertilization is not a prerequisite for the completion of meiosis, but required to trigger entry into the first S phase and the subsequent cleavage cycles. In starfish Asterina pectinifera (renamed to Patiria pectinifera in 2007 at the NCBI Taxonomy Browser), the Mos-MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase)-Rsk (p90 ribosomal S6 kinase, p90Rsk) pathway causes the G1-phase arrest at the pronucleus stage (6–10). Fertilization induces degradation of Mos to shutdown this pathway, leading to the first S phase with no requirement of new protein synthesis. However, it remains unclear how p90Rsk negatively controls the G1/S-phase transition, or to which stage the initiation complex for DNA replication is assembled in unfertilized G1-phase eggs. Here we show that the p90Rsk-dependent G1-phase arrest of unfertilized starfish eggs occurs at the pre-RC stage, and that in the absence of Cdk1 and Cdk2 activities and Cdc7 accumulation, inactivation of p90Rsk is necessary and sufficient for further loading of Cdc45 and the subsequent initiation of DNA replication.

Results

Female Pronuclei in Unfertilized Eggs Are Licensed for DNA Replication.

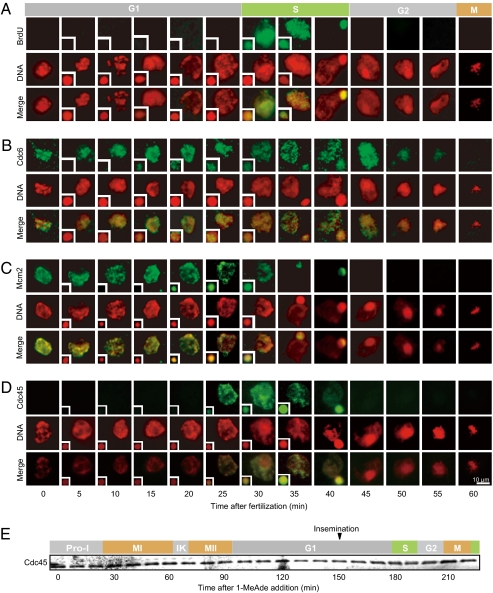

We first determined the timing of S phase. A 5-min pulse incorporation of BrdU to DNA indicates that the first S phase begins ∼30 min and ends ∼45 min after insemination of eggs arrested at G1 phase (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1) (11). In parallel, congression and fusion between female and male pronuclei occurred (12), while DNA replication appeared to start separately and almost simultaneously in each pronucleus and then to continue for a little longer period in male pronuclei. Thereafter, M phase started at ∼60 min (Fig. 1A and Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

In female pronuclei of starfish eggs, chromatin is loaded with Cdc6 and Mcm2 before fertilization, and then with Cdc45 after fertilization at G1/S-phase transition. (A) Mature eggs, which were arrested at G1 phase after completion of meiosis II, were inseminated. To monitor DNA replication, every 5 min, fertilized eggs were pulse labeled for 5 min with BrdU, extracted, and immunostained with anti-BrdU antibody (green). DNA was stained with DAPI (red). Insets indicate male chromatin, and main figures indicate female chromatin or fused chromatin. (B–D) Every 5 min, isolated eggs were extensively extracted and then immunostained with anti-starfish Cdc6 antibody (B, green), anti-starfish Mcm2 antibody (C, green), and anti-starfish Cdc45 antibody (D, green). (Scale bar, 10 μm.) (E) Cdc45 protein is detectable in immature oocytes and its levels remain constant during meiotic and cleavage cycles.

To investigate assembly of the initiation complex for DNA replication before and after fertilization, we isolated cDNAs of starfish orthologs of Cdc6, Mcm2, Mcm7, and Cdc45 and raised antibodies to these proteins (Figs. S2 A–D and S3 A–D). All of these proteins were detectable in unfertilized eggs, and their protein levels remained constant during cleavage cycles (Fig. 1E for Cdc45 and Fig. S3H for Cdc6 and Mcm2). Both Cdc6 and Mcm2 were already detectable on chromatin of female pronuclei in unfertilized eggs arrested at G1 phase (Fig. 1B and C; 0 min). After fertilization, they remained localized on chromatin at almost constant levels until S phase. As DNA replication progressed, the Mcm2 signal decreased in mid-S phase (Fig. 1C; 35 min) and disappeared in late S phase (Fig. 1C; 40 min), whereas the Cdc6 signal remained until early G2 phase (Fig. 1B; 45 min), declined after mid-G2 phase (Fig. 1B; 50 min), and finally disappeared at M phase (Fig. 1B; 60 min). Similar behavior of Mcm was observed with other antibodies against human Mcm2 (BM28) and starfish Mcm7 (Fig. S4).

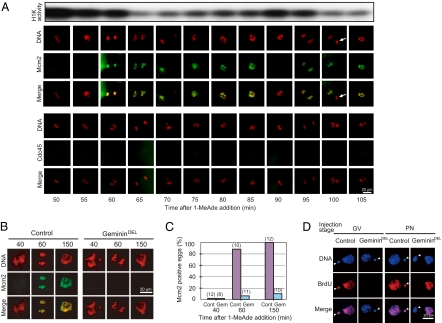

Before the G1 arrest, Mcm2 was detectable on chromatin at each end of meiosis I and II during meiotic cycle, coincidentally with decreased levels of cyclin B-Cdk1 activity (Fig. 2A). The Mcm2 loading was dependent on geminin degradation, supporting that it was mediated by Cdt1 (Fig. 2 B and C) (13). Consistently, undegradable form of geminin prevented DNA replication in female pronuclei after fertilization, when it was introduced into oocytes before, but not after, meiotic maturation (Fig. 2D). Taken together, pre-RC is already formed in female pronuclei of unfertilized eggs; that is, female pronuclei are licensed for DNA replication before fertilization.

Fig. 2.

Loading of Mcm2 onto chromatin during meiosis is blocked by geminin. (A) At each end of meiosis I and II, Mcm2, but not Cdc45, is loaded onto chromatin. Immature oocytes were treated with 1-MeAde to undergo meiotic maturation. Beginning at 50 min, every 5 min, oocytes were either fixed for immunostaining with anti-Mcm2 (green) or anti-Cdc45 antibodies along with DAPI (red) staining, or extracted for histone H1 kinase assay to monitor meiotic cell cycle progression (Top). Note that Mcm2 was undetectable on chromatin until 55 min (metaphase I) and at 90 min (metaphase II). Arrow indicates the second polar body. (B–D) Nondegradable geminin inhibits loading of Mcm2 onto chromatin during meiosis, and hence prevents DNA replication after fertilization. Immature oocytes were injected with nondegradable form of geminin (gemininDEL, Gem), wild-type (degradable) geminin (B, control; C, Cont), or control buffer (D, control) and then treated with 1-MeAde to undergo meiotic maturation. At 40 min (metaphase I), 60 min (anaphase I), or 150 min (G1 phase after completion of meiosis II), oocytes were fixed for staining with anti-Mcm2 antibody or with DAPI (B). Number of eggs examined for loading of Mcm2 onto chromatin is indicated in parentheses (C). Alternatively, 150 min after 1-MeAde addition, mature eggs were inseminated in the presence of BrdU, and 40 min later, DNA replication was examined (D, GV). For reference, after meiotic maturation, G1-phase eggs were injected with nondegradable form of geminin and then inseminated (D, PN). Note that BrdU incorporation (red) was undetectable both in female and male (arrowhead) pronuclei (D, GV), though detectable only in female pronucleus (D, PN), showing that only the female, but not the male, pronucleus is licensed for DNA replication before fertilization.

In male pronuclei, both Cdc6 and Mcm2 were undetectable immediately after fertilization, and then soon became detecteable (Fig. 1 B and C Insets; 0∼20 min), indicating that male pronulei become licensed after fertilization. Indeed, undegradable form of geminin prevented DNA replication in male pronuclei (but not in female pronuclei) after fertilization, even when it was introduced into G1-phase eggs (Fig. 2D, arrowhead). After the loading onto chromatin, Cdc6 and Mcm2 behaved similarly to those in female pronuclei.

Replication Origins Are Not Activated in Female Pronuclei of Unfertilized Eggs.

In contrast to Cdc6 and Mcm2, Cdc45 was undetectable on chromatin in female pronuclei of unfertilized G1-phase eggs (Fig. 1D; 0 min). During meiotic maturation before the G1 arrest, Cdc45 protein was already present in the oocyte but undetectable on the chromatin, even though the Mcm2 loading occurred at each end of meiosis I and II (Figs. 1E and 2A). After fertilization, however, Cdc45 became detectable on chromatin both in female and male pronuclei just before the start of S phase (Fig. 1D; 25 min). Thereafter, the signal of Cdc45 on chromatin increased to peak at the beginning of S phase, decreased along with the progression of S phase, and finally disappeared at the end of S phase (Fig. 1D; 30∼45 min). Fertilization thus caused the loading of Cdc45 onto chromatin, indicating that the female pronuclei in unfertilized eggs are licensed but that their replication origins are not activated. This implies that in G1 phase, unfertilized eggs arrest at a stage before pre-IC and most likely at the stage of pre-RC.

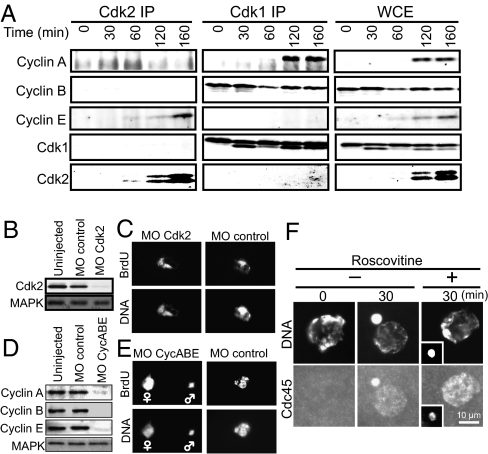

Cdk Activity and Cdc7 Synthesis Are Dispensable for Cdc45 Loading After Fertilization.

S-Cdk and Cdc7 (Dbf4-dependent kinase, DDK) are implicated in the Cdc45 loading onto chromatin in yeast, frog eggs, and mammalian cultured cells (1, 2, 14). To investigate whether this is the case in fertilized starfish eggs, we isolated cDNAs of starfish orthologs of cyclin E and Cdk2, and raised antibodies against these proteins (Figs. S2 E and F and S3 E and F). Both proteins were undetectable in immature oocytes and began to accumulate after meiotic reinitiation, but their levels did not fluctuate during the cleavage cycles (Fig. 3A and Fig. S3I). Cdk2 was predominantly associated with cyclin E, whereas Cdk1 was associated with each of cyclin A and cyclin B (Fig. 3A; see also ref. 15). Neither a single knockdown of Cdk2 nor a triple knockdown of cyclins A, B, and E with respective morpholino oligonucleotides prevented initiation of DNA replication after fertilization (Fig. 3 B–E). Consistently, in the presence of Cdk inhibitor roscovitine, Cdc45 became detectable both on maternal and paternal chromatin almost at normal timing (Fig. 3F). Thus, whereas the G1-phase eggs of starfish are arrested at pre-RC stage, cyclin A-Cdk1, cyclin B-Cdk1, and cyclin E-Cdk2 are all not essential for further loading of Cdc45 and the subsequent initiation of DNA replication after fertilization.

Fig. 3.

Cdc45 is loaded onto chromatin and DNA replication is initiated in the absence of Cdk activity when G1-phase eggs are fertilized. (A) In starfish eggs, Cdk1 associates with cyclin A and cyclin B, and Cdk2 associates predominantly with cyclin E. Immature oocytes were treated with 1-MeAde to resume meiosis, and then at 50 min, meta-I oocytes were inseminated to initiate embryonic cycles after completion of meiosis II. Oocyte or egg extracts were prepared at 0 min (immature), 30 min (GVBD), 60 min (interkinesis), 120 min (the first M phase in cleavage cycle), and 160 min (the second M phase) (Fig. S3I). Whole-cell extracts (WCE), and their immunoprecipitates with anti-Cdk2 (Cdk2 IP) or anti-Cdk1 (Cdk1 IP) were immunoblotted with each of cyclins A, B, and E, and Cdk1 and Cdk2. Lower band of Cdk1 corresponds to its active form. (B–E) A single knockdown of Cdk2 (B and C) or a triple knockdown of cyclins A, B, and E (D and E) does not prevent DNA replication induced by fertilization. Immature oocytes were injected with morpholino oligonucleotides against Cdk2 or cyclins A and E, and then treated with 1-MeAde to resume meiosis. At 120–150 min after 1-MeAde addition, mature eggs that had been injected with cyclins A and E morpholino oligonucleotides were further injected with morpholino oligonucleotide against cyclin B. At 180 min, all eggs were inseminated in the presence of BrdU. Successful insemination was confirmed by elevation of fertilization envelope. Fifty (B and C) or 80 (D and E) min later, eggs were recovered to confirm knockdown of Cdk2 (B, MO Cdk2) or cyclins A, B, and E (D, MO CycABE) with immunoblots and to examine BrdU incorporation (C and E). As controls, respective control morpholino oligonucleotides were injected (MO Control). In the triple knockdown (E), significant delay was observed in BrdU incorporation into female pronucleus chromatins. MAPK was used as a loading control for immunoblots (B and D). Knockdown of Cdk2 or cyclins A and E did not affect the meiotic cell-cycle progression. (F) Inhibition of Cdk activity does not affect Cdc45 loading onto chromatin after fertilization. G1 eggs were inseminated in the presence or absence of 10 μM roscovitine, followed by examination of Cdc45 loading at 30 min. Note that BrdU incorporation (E) or Cdc45 loading (F) was observed separately in female and male pronuclei. Such a failure in pronuclear congression is evidence for sufficient knockdown of cyclin B (E) or sufficient inhibition of Cdk (F), because pronuclear congression requires low levels of cyclin B-Cdk1 activity (12).

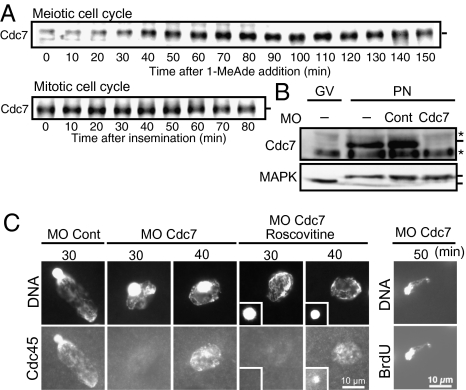

We then isolated cDNA of starfish ortholog of Cdc7 and raised its antibody (Figs. S2G and S3G). Cdc7 protein was detectable at low level in immature oocytes, accumulated during meiotic maturation, and remained at elevated levels during the first cleavage cycle (Fig. 4A). However, when accumulation of Cdc7 was prevented with its morpholino oligonucleotide, Cdc45 became detectable on chromatin after fertilization with ∼10-min delay compared with control eggs, followed by BrdU incorporation (Fig. 4 B and C). No further delay in the Cdc45 loading was detectable, even when fertilized eggs incurred both Cdk inhibition and Cdc7 knockdown (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Cdc45 is loaded onto chromatin and DNA replication is initiated in the absence of new synthesis and accumulation of Cdc7 when G1-phase eggs are fertilized. (A) On immunoblots, Cdc7 protein was slightly detectable in immature oocytes. Its levels increased during meiotic maturation and remained elevated in the first cleavage cycle. (B and C) Delayed loading of Cdc45 occurs in Cdc7-knocked-down eggs after fertilization. Immature oocytes (GV) were injected with morpholino oligonucleotide against Cdc7 and then treated with 1-MeAde to resume meiosis. Female pronucleus stage eggs (PN) were either processed to examine Cdc7 protein levels (B) or inseminated in the presence or absence of 10 μM roscovitine to examine Cdc45 loading at 30 and 40 min or BrdU incorporation at 50 min (C). As controls, control morpholino oligonucleotide was injected (MO Cont) or not (−). Note that paternal DNA is discerned as a bright spot within zygotic nucleus in the absence of roscovitine, whereas male (Inset) and female pronuclei are separated in the presence of roscovitine. Asterisks in the Cdc7 blots indicate nonspecific bands, and upper and lower bands of MAPK correspond to active and inactive form, respectively (B).

Taken together, both Cdk and Cdc7 are likely to be dispensable for the Cdc45 loading onto chromatin after fertilization. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that Cdk may affect the efficiency of DNA replication (16), and that very low level of Cdc7 detectable in immature oocytes remained even after Cdc7 knockdown and contributed to the delayed formation of the pre-IC, whereas the pre-IC would be formed at normal timing if new synthesis and accumulation of Cdc7 occur during meiotic maturation.

Loading of Cdc45 onto Chromatin Is Negatively Regulated by p90Rsk.

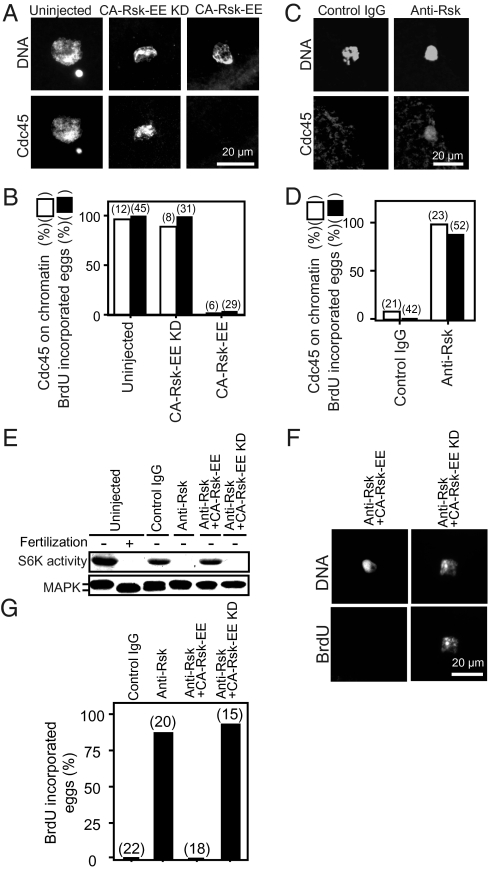

How then is the loading of Cdc45 onto chromatin regulated upon fertilization? Because the Cdc45 loading coincided with inactivation of p90Rsk after fertilization (Fig. S1A), we tested how p90Rsk activity is related to Cdc45 loading by manipulating the activity of p90Rsk in eggs. When unfertilized G1-phase eggs received an injection with a constitutively active mutant protein of p90Rsk (CA-Rsk-EE) that can maintain Rsk activity (9), neither the Cdc45 loading onto chromatin nor the subsequent DNA replication occurred even after fertilization (Fig. 5 A and B). Conversely, when unfertilized G1-phase eggs received an injection with the neutralizing antibody against starfish p90Rsk that can inhibit its activity (9), Cdc45 was loaded onto chromatin in female pronucleus, and the subsequent DNA replication was induced in the absence of fertilization (Fig. 5 C and D). Further, coinjection of CA-Rsk-EE with the neutralizing anti-p90Rsk antibody restored the arrest at G1 phase (Fig. 5 E–G). Thus, inactivation of p90Rsk is necessary and sufficient for Cdc45 loading onto chromatin in unfertilized G1-phase eggs.

Fig. 5.

Inactivation of p90Rsk is necessary and sufficient for loading of Cdc45 onto chromatin and the subsequent initiation of DNA replication in G1-phase-arrested starfish eggs. (A and B) Maintenance of p90Rsk activity prevents loading of Cdc45 onto chromatin and the subsequent DNA replication in fertilized eggs. Mature eggs after completion of meiosis II were uninjected or injected with 0.6 ng of either constitutively active p90Rsk (CA-Rsk-EE) or its control kinase-dead form (CA-Rsk-EE KD). Thereafter, these eggs were inseminated and incubated in the presence of BrdU and then fixed either at 30 min for anti-Cdc45 immunostaining or at 50 min for anti-BrdU immunostaining. Successful fertilization was confirmed by formation of fertilization membrane. (C and D) Inhibition of p90Rsk activity causes loading of Cdc45 onto chromatin and the subsequent DNA replication in the absence of fertilization. Unfertilized mature eggs were injected in the presence of BrdU with 3 ng of either neutralizing anti-p90Rsk antibody or control preimmune IgG, followed by incubation. Eggs were fixed either at 30 min for anti-Cdc45 immunostaining or at 60 min for anti-BrdU immunostaining. (E–G) Constitutively active p90Rsk restores G1-phase arrest in eggs injected with neutralizing anti-p90Rsk antibody. Unfertilized mature eggs were injected with neutralizing anti-p90Rsk antibody along with CA-Rsk-EE or control CA-Rsk-EE KD. After 60 min incubation in the presence of BrdU, eggs were fixed for anti-BrdU immunostaining (F and G). Egg lysates were either immunoblotted with anti-MAPK antibody, or assayed for phosphorylation of GST-S6 (S6K activity) (E). DNA was stained with DAPI. Number of eggs examined for Cdc45 loading or BrdU incorporation are indicated in parentheses (B, D, and G).

Discussion

The present observations show that in unfertilized starfish eggs, G1-phase arrest occurs at the stage of pre-RC. Fertilization targets the pre-RC/pre-IC transition through loading of Cdc45 onto chromatin, which requires p90Rsk inactivation but neither Cdk activity nor Cdc7 accumulation, resulting in initiation of DNA replication.

As for the initiation of DNA replication at fertilization, there are striking differences in the regulatory mechanisms used by different species. In Xenopus, Cdc6 is the missing factor in immature oocytes (17), and cyclin E is necessary for DNA replication in egg extracts (18), whereas the Mos-MAPK-Rsk pathway is unlikely to play any role for progression through G1 phase due to its preceding inactivation (19, 20). In sea urchin eggs, which also arrest at G1 phase until fertilization, conflicting reports have accumulated: MAPK inactivation is necessary for DNA replication (21); Cdk activity is not required for DNA replication (22, 23); MAPK inactivation does not cause DNA replication (24); and MAPK activation and cyclin E are required for DNA replication (25). No study, however, examined the immediate downstream of MAPK or the behavior of Mcms and Cdc45, excluding further comparison with starfish egg system.

In eukaryotic cells, there is a major cell-cycle checkpoint at late G1 phase called “START” in yeast or “restriction point” in mammalian cells, after which commitment to a new cell cycle is irreversible (26). As the G1 checkpoint occurs at the stage of pre-RC (14), the arrest stage appears to be conserved in unfertilized G1-phase eggs as well. However, both types of arrest are unlikely to be equivalent. In the G1 checkpoint, the pre-RC/pre-IC transition is intervened by transcriptional control (27) that leads to the activation of Cdk and Cdc7, which support the Cdc45 loading. In contrast, the Cdc45 loading by fertilization does not even require translation. Indeed, there is an apparent similarity between the G1 checkpoint arrest in budding yeast and the G1 arrest in unfertilized starfish eggs because both require Fus3/MAPK, whereas Fus3 directly targets Far1, an CDK inhibitor, resulting in transcriptional repression toward prevention of DNA replication (28). Such a different dependence on transcription may explain the different requirement both of Cdk and Cdc7 for the Cdc45 loading. It is plausible that in case of fertilization, Cdk- and Cdc7-dependent processes could be accomplished during meiotic maturation.

So far, p90Rsk is a unique negative regulator for the pre-RC stage. In this arrest, p90Rsk should finally affect replication initiation proteins that are engaged in loading of Cdc45 onto chromatin, e.g., GINS, Dpb11/Cut5/Mus101/TopBP1, Mcm10, Sld2/RecQL4, or Ctf4/And-1 (1, 2, 29, 30). Our preliminary observations suggest that p90Rsk do not directly phosphorylate Cdc45 in vitro, whereas starfish Cut5 contains consensus sequences for phosphorylation by p90Rsk. In somatic cell cycle, however, MAPK-p90Rsk signaling positively regulates the G1 progression (31). If so, the direct target of p90Rsk in unfertilized starfish eggs is unlikely to be a replication initiation protein itself but a specific mediator to the initiation complex for DNA replication, as in a manner that p90Rsk directly targets Erp1/Emi2, an APC/C inhibitor, but not the APC/C itself, in metaphase arrest of meiosis II in Xenopus eggs (19, 20). Further studies will contribute to elucidating the rewiring of signal transduction pathways to different cell-cycle controls.

Materials and Methods

Oocytes and Eggs.

Fully grown, immature oocytes were isolated from the starfish Asterina pectinifera. Oocyte maturation was induced by 1 μM 1-methyladenine (1-MeAde), the starfish maturation-inducing hormone (32). Some 150 min later, mature eggs with a female pronucleus, which were arrested at G1 phase after completion of meiosis, were inseminated to start the embryonic mitotic cycle (7). Microinjection into eggs was performed as described (33).

Immunofluorescence Staining.

Immunofluorescent or DAPI staining was performed essentially as described (12). Additional information, including antibody preparation, morpholino-mediated knockdown, and others, see SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas J. McGarry for geminin and gemininDEL constructs; Angel R. Nebreda for CA-Rsk-EE constructs; Yuichi Kumaki and Masato Yoshizawa for help in preparing antibodies; Keita Ohsumi, Eiichi Okumura, and Mari Iwabuchi for discussion; and Mark Terasaki for reading the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from MEXT Japan (to K.T. and T.K.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) (accession nos. AB474909, AB474910, AB474911, AB474912, AB481214, AB481376, and AB530248).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/1000587107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Machida YJ, Hamlin JL, Dutta A. Right place, right time, and only once: Replication initiation in metazoans. Cell. 2005;123:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sclafani RA, Holzen TM. Cell cycle regulation of DNA replication. Annu Rev Genet. 2007;41:237–280. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kearsey SE, Cotterill S. Enigmatic variations: Divergent modes of regulating eukaryotic DNA replication. Mol Cell. 2003;12:1067–1075. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00441-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meijer L, Guerrier P. Maturation and fertilization in starfish oocytes. Int Rev Cytol. 1984;86:129–196. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page AW, Orr-Weaver TL. Stopping and starting the meiotic cell cycle. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:23–31. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishimoto T. Cell-cycle control during meiotic maturation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:654–663. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tachibana K, Machida T, Nomura Y, Kishimoto T. MAP kinase links the fertilization signal transduction pathway to the G1/S-phase transition in starfish eggs. EMBO J. 1997;16:4333–4339. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tachibana K, Tanaka D, Isobe T, Kishimoto T. c-Mos forces the mitotic cell cycle to undergo meiosis II to produce haploid gametes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:14301–14306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.26.14301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mori M, Hara M, Tachibana K, Kishimoto T. p90Rsk is required for G1 phase arrest in unfertilized starfish eggs. Development. 2006;133:1823–1830. doi: 10.1242/dev.02348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hara M, Mori M, Wada T, Tachibana K, Kishimoto T. Start of the embryonic cell cycle is dually locked in unfertilized starfish eggs. Development. 2009;136:1687–1696. doi: 10.1242/dev.035261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nomura A, Maruyama YK, Yoneda M. Initiation of DNA replication cycle in fertilized eggs of the starfish, Asterina pectinifera. Dev Biol. 1991;143:289–296. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(91)90079-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tachibana K, Hara M, Hattori Y, Kishimoto T. Cyclin B-cdk1 controls pronuclear union in interphase. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1308–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGarry TJ, Kirschner MW. Geminin, an inhibitor of DNA replication, is degraded during mitosis. Cell. 1998;93:1043–1053. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diffley JF. Regulation of early events in chromosome replication. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R778–R786. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okano-Uchida T, et al. In vivo regulation of cyclin A/Cdc2 and cyclin B/Cdc2 through meiotic and early cleavage cycles in starfish. Dev Biol. 1998;197:39–53. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krasinska L, et al. Cdk1 and Cdk2 activity levels determine the efficiency of replication origin firing in Xenopus. EMBO J. 2008;27:758–769. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pelizon C. Down to the origin: Cdc6 protein and the competence to replicate. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:110–113. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jackson PK, Chevalier S, Philippe M, Kirschner MW. Early events in DNA replication require cyclin E and are blocked by p21CIP1. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:755–769. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.4.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishiyama T, Ohsumi K, Kishimoto T. Phosphorylation of Erp1 by p90rsk is required for cytostatic factor arrest in Xenopus laevis eggs. Nature. 2007;446:1096–1099. doi: 10.1038/nature05696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inoue D, Ohe M, Kanemori Y, Nobui T, Sagata N. A direct link of the Mos-MAPK pathway to Erp1/Emi2 in meiotic arrest of Xenopus laevis eggs. Nature. 2007;446:1100–1104. doi: 10.1038/nature05688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carroll DJ, et al. The relationship between calcium, MAP kinase, and DNA synthesis in the sea urchin egg at fertilization. Dev Biol. 2000;217:179–191. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreau JC, et al. Cdk2 activity is dispensable for the onset of DNA replication during the first mitotic cycles of the sea urchin early embryo. Dev Biol. 1998;200:182–197. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.8961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnackenberg BJ, Palazzo RE, Marzluff WF. Cyclin E/Cdk2 is required for sperm maturation, but not DNA replication, in early sea urchin embryos. Genesis. 2007;45:282–291. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang WL, Huitorel P, Geneviere A-M, Chiri S, Ciapa B. Inactivation of MAPK in mature oocytes triggers progression into mitosis via a Ca2+-dependent pathway but without completion of S phase. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3491–3501. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kisielewska J, Philipova R, Huang J-Y, Whitaker M. MAP kinase dependent cyclinE/cdk2 activity promotes DNA replication in early sea urchin embryos. Dev Biol. 2009;334:383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.07.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hartwell LH, Weinert TA. Checkpoints: Controls that ensure the order of cell cycle events. Science. 1989;246:629–634. doi: 10.1126/science.2683079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartwell LH, Kastan MB. Cell cycle control and cancer. Science. 1994;266:1821–1828. doi: 10.1126/science.7997877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Elion EA. Pheromone response, mating and cell biology. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:573–581. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labib K, Gambus A. A key role for the GINS complex at DNA replication forks. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Im JS, et al. Assembly of the Cdc45-Mcm2-7-GINS complex in human cells requires the Ctf4/And-1, RecQL4, and Mcm10 proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15628–15632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908039106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anjum R, Blenis J. The RSK family of kinases: Emerging roles in cellular signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:747–758. doi: 10.1038/nrm2509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanatani H, Shirai H, Nakanishi K, Kurokawa T. Isolation and identification of meiosis inducing substance in starfish. Nature. 1969;221:273–274. doi: 10.1038/221273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kishimoto T. Microinjection and cytoplasmic transfer in starfish oocytes. Methods Cell Biol. 1986;27:379–394. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(08)60359-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.