Abstract

Pregnancy-associated malaria (PAM) is a serious consequence of sequestration of Plasmodium falciparum-parasitized erythrocytes (PE) in the placenta through adhesion to chondroitin sulfate A (CSA) present on placental proteoglycans. Recent work implicates var2CSA, a member of the PfEMP1 family, as the mediator of placental sequestration and as a key target for PAM vaccine development. Var2CSA is a 350 kDa transmembrane protein, whose extracellular region includes six Duffy-binding-like (DBL) domains. Due to its size and high cysteine content, the full-length var2CSA extracellular region has not hitherto been expressed in heterologous systems, thus limiting investigations to individual recombinant domains. Here we report for the first time the expression of the full-length var2CSA extracellular region (domains DBL1X to DBL6ε) from the 3D7 parasite strain using the human embryonic kidney 293 cell line. We show that the recombinant extracellular var2CSA region is correctly folded and that, unlike the individual DBL domains, it binds with high affinity and specificity to CSA (KD = 61 nM) and efficiently inhibits PE from binding to CSA. Structural characterization by analytical ultracentrifugation and small-angle x-ray scattering reveals a compact organization of the full-length protein, most likely governed by specific interdomain interactions, rather than an extended structure. Collectively, these data suggest that a high-affinity, CSA-specific binding site is formed by the higher-order structure of the var2CSA extracellular region. These results have important consequences for the development of an effective vaccine and therapeutic inhibitors.

Keywords: malaria, pregnancy, plasmodium, chondroitin, structure

Pregnancy-associated malaria (PAM) results from massive accumulation of Plasmodium falciparum-parasitized erythrocytes (PE) and monocytes in the intervillous spaces of the placenta, causing severe clinical symptoms in the expectant mother and serious impairment to fetal development (1). Tropism of PE to the placenta is due to their capacity to bind chondroitin sulfate A (CSA) (2), the glycan component of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPG) located on the syncytiotrophoblast lining. This interaction is highly specific for CSA since other sulfated glycosaminoglycans, such as chondroitin sulfate B and C, heparin and heparan sulfate, do not inhibit parasite adhesion to placental CSPG (3). CSA binding has been linked to the expression of the var2CSA variant of P. falciparum Erythrocyte Membrane Protein 1 (PfEMP1) (4, 5), a family of parasite adhesins presented on the surface of PE and displaying diverse specificities to host cell receptors (6). Of the approximately 60 variants comprising the PfEMP1 family, var2CSA is one of the most conserved between different parasite strains and at least one orthologue gene is consistently found in parasite isolates (7). Var2CSA is the only PfEMP1 variant whose transcription is upregulated in placental PE and laboratory parasites selected for CSA binding (5, 8–10). Although other P. falciparum genes show variable degrees of upregulation in clinical placental isolates, there is no evidence for a direct role in the adhesion process (11, 12). Furthermore, studies using var2CSA-knockout parasites have demonstrated that no other parasite ligand promotes extensive CSA and placental adhesion (13–15).

Several indications support var2CSA as a vaccine candidate for PAM. Importantly, women develop antibodies that block CSA adhesion of placental isolates after one or two pregnancies, leading to naturally acquired immunity (16–18). Moreover, antibodies induced by recombinant var2CSA domains inhibit the binding of placental parasite isolates to CSA (19, 20). Recognition of var2CSA recombinant domains by sera from donors in malaria-endemic regions is specific to the female gender, correlates directly with gravidity of the donor and transcends the geographic origin of the sera (21, 22). These observations strongly suggest that var2CSA carries conserved, protective epitopes and reinforce the view that var2CSA is an excellent candidate for vaccine development.

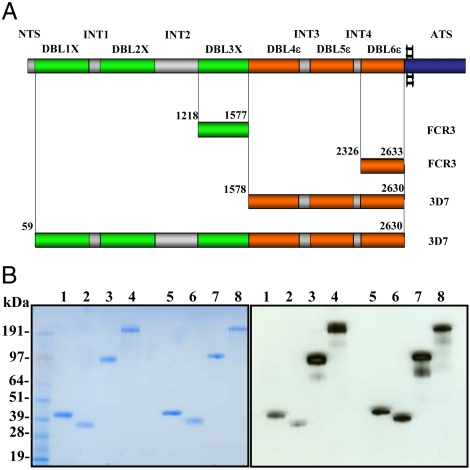

Var2CSA, a large, 350 kDa transmembrane protein, includes six Duffy-Binding-Like (DBL) domains in its extracellular region—three belonging to class X and three to class ε—and four interdomain regions (Fig. 1A). Different studies indicate that several domains of var2CSA bind CSA (DBL2X, DBL3X, DBL5ε, and DBL6ε) (9, 23, 24), suggesting that multivalent CSA-binding interactions might be involved in placental sequestration. However, recent work has questioned the ligand specificity of isolated domains (25) and has suggested that a higher-order organisation of the extracellular region of PfEMP1, determined by well defined interdomain contacts, is a prerequisite for creating a native CSA-specific binding site. In the present study, we assess this hypothesis by successfully expressing the complete extracellular region of var2CSA (domains DBL1X to DBL6ε) in a heterologous system. Biophysical and biological assays confirm that the recombinant extracellular var2CSA is correctly folded and functional. Furthermore, structural characterization by analytical ultracentrifugation (AUC) and small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) reveals a compact shape, compatible with the idea that a higher-order structure is essential for the formation of a high-affinity and specific CSA-binding site.

Fig. 1.

Recombinant 3D7-DBL1X-6ε is expressed in HEK293 cells. (A). Schematic view of the var2CSA domain organization and sequence limits of the recombinant domains studied (FCR3-DBL3X, FCR3-DBL6ε, 3D7-DBL4ε-6ε, and 3D7-DBL1X-6ε). It comprises six Duffy-binding-like domains (DBL1X to DBL6ε) and four interdomain regions (INT1-4) in the extracellular region, a transmembrane segment and acidic C terminus sequence (ATS). DBL1X, DBL2X, and DBL3X are green; DBL4ε, DBL5ε and DBL6ε are orange; N-terminal sequence (NTS) and interdomain regions (INT) are gray; the transmembrane and ATS regions are blue. The length of each bar corresponds to the domain size. (B). Purification of var2CSA derived proteins expressed in HEK293 and E. coli. SDS-PAGE Criterion XT Precast 4–12% Bis-Tris gel under reducing and nonreducing conditions was loaded with purified FCR3-DBL3X, FCR3-DBL6ε, 3D7-DBL4ε-6ε and 3D7-DBL1X-6ε. Protein was visualized with Coomassie blue (left) or transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane to detect recombinant protein using antiHis tag antibodies (right). Lanes 1-4: nonreduced FCR3-DBL3X, FCR3-DBL6ε, 3D7-DBL4ε-6ε, 3D7-DBL1X-6ε; lanes 5–8: reduced FCR3-DBL3X, FCR3-DBL6ε, 3D7-DBL4ε-6ε, 3D7-DBL1X-6ε.

Results

Var2CSA Extracellular Region is Successfully Expressed in HEK293 Cells.

Var2CSA is a large protein with a 300 kDa extracellular region, a transmembrane segment and a short, conserved intracellular domain (Fig. 1A). Due to its large size and the presence of more than 100 cysteines, expression of the entire extracellular domain has been unsuccessful to date. We have used the human embryonic kidney cell line (HEK293) heterologous expression system to obtain multidomain recombinant proteins, including the complete extracellular region of var2CSA (Fig. 1A). We attempted to express var2CSA constructs from both the FCR3 and 3D7 laboratory strains but only the latter gave yields of the multidomain proteins that permitted functional and biophysical studies. The 3D7 var2CSA extracellular region, 3D7-DBL1X-6ε, containing all DBL domains and interdomain regions, and the multidomain, 3D7-DBL4ε-6ε, were successfully expressed as soluble protein secreted into the culture supernatant (Fig. 1B). The yields after purification were ∼5 and 0.5 mg per liter of culture for 3D7-DBL4ε-6ε and 3D7-DBL1X-6ε, respectively. We also expressed DBL3X and DBL6ε from the FCR3 strain as soluble proteins in Escherichia coli in order to compare these domains, previously characterized for CSA binding, with the multidomain proteins. The yield for both domains was around 10 mg per liter of culture.

All recombinant proteins were purified to better than 95% purity. Under reducing conditions in SDS-PAGE, all four proteins migrated according to their expected molecular weight: FCR3-DBL3X (43 kDa), FCR3-DBL6ε (38 kDa), 3D7-DBL4ε-6ε (125 kDa) and 3D7-DBL1X-6ε (300 kDa) (Fig. 1B), while under nonreducing conditions a shift in the migration of all proteins confirmed the presence of disulfide bridges. N-terminal sequencing, SDS-PAGE and Western blots indicated that the proteins remained intact, without proteolytic degradation occurring during the purification process.

Circular Dichroism Analysis of the Recombinant Var2CSA Constructs.

Far-UV CD spectra were recorded for all four recombinant proteins under native conditions. Each exhibited a peak at 195 nm and two troughs at 208 nm and 222 nm, respectively, characteristic of α-helical proteins (Fig. S1). The secondary structure content of the recombinant proteins calculated by spectrum deconvolution (Table 1) is consistent with that observed in the crystal structures of DBL domains; PkDBP (26), EBA-175 (27), DBL3X (28, 29), and DBL6ε (30). We also analyzed the thermal unfolding of each recombinant protein by monitoring the change in ellipticity at 222 nm. In all cases, a sharp decrease in signal occurred in the 68–75 °C temperature range (Table 1), showing that similar intradomain bonds are involved in the folding stability of single- and multidomain proteins and thus indicative of native folding. This stability can be partly attributed to a network of conserved, buried salt bridges between subdomains 2 and 3 of the DBL fold.

Table 1.

Recombinant protein secondary structure analysis monitored by CD

| Domain | Helix (%) | Strand (%) | Turns (%) | Other (%) | Tm (°C) |

| DBL3X | 61 | 5 | 13 | 21 | 67.8 |

| DBL6ε | 70 | 1 | 11 | 18 | 74.6 |

| DBL4ε-6ε | 60 | 4 | 14 | 22 | 72.8 |

| DBL1X-6ε | 56 | 6 | 16 | 22 | 72.9 |

Low-Resolution Structure of Var2CSA.

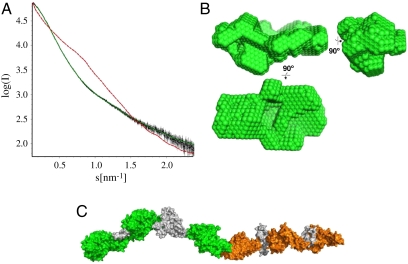

We performed AUC and SAXS experiments to determine the oligomeric state and overall shape of the recombinant proteins. AUC sedimentation velocity experiments suggest that the proteins are monomeric, with a low percentage of aggregates or multimeric forms, except for FCR3-DBL6ε which shows a higher aggregation propensity, with only 50% in monomeric form. The experimental sedimentation coefficients and f/f0 frictional ratios of FCR3-DBL3X and FCR3-DBL6ε (Table 2) were compatible with theoretical values calculated from published crystal structures (28–30). While the f/f0 of single domains (≈1.3) is characteristic of hydrated globular proteins, that of 3D7-DBL4ε-6ε and 3D7-DBL1X-6ε is significantly higher (≈1.5), suggesting that the multidomain proteins are slightly more elongated than single domains. The solution structure of 3D7-DBL1X-6ε was further analyzed by SAXS. An extended “beads on a string” model of the var2CSA extracellular region was generated using the coordinates of known crystal structures to account for the six DBL domains and four interdomain regions, and the theoretical scattering curve for this model was calculated and compared with experimental data (Fig. 2). The extended model (Fig. 2C) clearly does not fit the data (Fig. 2A, χ2 = 68.9). A comparison of the theoretical sedimentation coefficient and frictional ratio calculated for the extended model (Table 2) with the AUC data confirmed this result, showing that the shape of the protein in solution is more globular, with the domains folding upon themselves. The size of 3D7-DBL1X-6ε calculated from the SAXS data gave a radius of gyration (Rg) of 6.24 nm and 18.5 nm as its longest dimension (Dmax), both significantly lower than for the extended model (Table S2). The experimentally determined volume matched that of the extended model, indicating that the mass of protein in the model corresponds to that of the recombinant protein but that the latter is more compact.

Table 2.

Structural and hydrodynamic parameters derived from AUC and SAXS

| Experimental data (AUC) | Calculated values | |||

| S20,w(S) | f/f0 | S20,w(S) | f/f0 | |

| DBL3X | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 3.0* | 1.3* |

| DBL6ε | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 2.8* | 1.3* |

| DBL4ε-6ε | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | nd | nd |

| DBL1X-6ε | 10.1 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 9.8† | 1.5† |

| Extended DBL1X-6ε model | nd | nd | 7.4‡ | 2.0‡ |

*from crystal structures

†the ab initio SAXS model

‡from the extended model

Fig. 2.

Global shape of 3D7-DBL1X-6ε obtained from SAXS. (A). Plot of x-ray intensity log(I) against the scattering angle (s = 4π sin Θ/λ). The data points are black, calculated 3D7-DBL1X-6ε ab initio model curve is green and that corresponding to the theoretical extended model scattering curve is a red dashed line. (B). Orthogonal views of the 3D7-DBL1X-6ε ab initio model. (C). The theoretical extended model of the extracellular region of var2CSA, constructed as described in SI Text, shown to the same scale as the ab initio model in (B). DBL domains and interdomain regions are colored as in Fig. 1A.

Ab-initio modeling was carried out to determine the shape of 3D7-DBL1X-6ε and the most representative model is shown in Fig. 2B (χ2 = 2.4). its volume compares well with the sum of the individual domain volumes (Table S2) and it is compatible with the AUC results (Table 2). It was not possible to unambiguously determine the configuration of the ten structural modules within this low-resolution envelope by rigid-body fitting, although it did produce compact models compatible with the ab initio model dimensions.

3D7-DBL1X-6ε Binds Specifically to CSA.

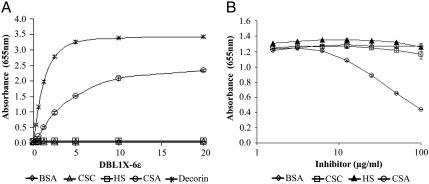

The functional integrity of the recombinant proteins was tested by direct ELISA using different plate-coated glycosaminoglycans (GAG) including the CSA proteoglycan decorin, CSA, chondroitin sulfate C (CSC), and heparan sulfate (HS) (Fig. 3A and Fig. S2). Of the four proteins, only 3D7-DBL1X-6ε bound to decorin and CSA in a dose-dependent manner and did not bind to any of the other sulfated GAG tested or to BSA (Fig. 3A). We observed a stronger signal with decorin than with free CSA, in accord with a previous report that showed stronger adhesion of CSA-binding PE to decorin than to bovine tracheal CSA (25). This could be due to the large protein core (40 kDa) in decorin allowing a more efficient coating of the plastic microplate or to differences in the chain length or sulfate content of the CSA chains. Curiously, it has been previously shown that single var2CSA DBL domains bind nonspecifically and with low affinity to different sulfated GAG (25, 30). Here, we did not detect any binding by individual DBL domains, FCR3-DBL3X and FCR3-DBL6ε (Fig. S2), indicating that the ELISA was either highly specific or not sensitive enough to detect low-affinity interactions. By contrast, our results indicate that 3D7-DBL1X-6ε binds specifically and with high affinity to CSA.

Fig. 3.

3D7-DBL1X-6ε binds specifically to CSA. (A). ELISA-based direct binding assay of the 3D7-DBL1X-6ε to different sulfated glycosaminoglycans. Increasing concentrations of recombinant 3D7-DBL1X-6ε at serial dilutions of 0.31–20 μg/mL were added to wells previously coated with different glycosaminoglycans: decorin, CSA, CSC, heparan sulfate (HS). (B). Competitive inhibition of binding of recombinant DBL domains to decorin using various glycosaminoglycans. Recombinant proteins at 1 μg/mL were premixed with increasing amounts of GAG, 0.156–100 μg/mL (CSA, CSC, or HS) and incubated in plates previously coated with decorin.

To further assess the CSA-binding specificity of 3D7-DBL1X-6ε, we tested whether other sulfated GAG could inhibit its binding to decorin. Decorin-coated plates were incubated with a constant concentration of recombinant 3D7-DBL1X-6ε premixed with increasing concentrations of CSA, CSC, and HS (Fig. 3B). In these assays, binding of 3D7-DBL1X-6ε to decorin was inhibited by CSA, but not by the other sulfated GAG, in a dose-dependent manner. Taken together, these results show that only the complete extracellular domain of var2CSA binds specifically and with high affinity to CSA.

3D7-DBL1X-6ε Binds with High Affinity to Human Placental CSPG.

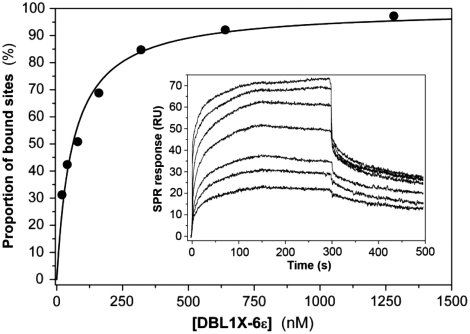

The affinities of the interactions between placental CSPG and the four recombinant proteins were investigated by real-time surface plasmon resonance (SPR). The concentration dependence of the steady-state response obtained by flowing the proteins over immobilized human CSPG in a sensor chip was used to determine the binding constants (KD) (Fig. 4, Table 3). KD is in the nanomolar range for 3D7-DBL1X-6ε, while the affinities of the other recombinant proteins are in the micromolar range (Table 3). Indeed, the affinity was more than 1,500 times higher for 3D7-DBL1X-6ε than for the single DBL domains (FCR3-DBL3X and FCR3-DBL6ε) and 125 times higher than for 3D7-DBL4ε-6ε, indicating that only 3D7-DBL1X-6ε binds with high affinity to human placental CSPG.

Fig. 4.

3D7-DBL1X-6ε binds with high affinity to human placental CSPG. From surface plasmon resonance binding experiments using soluble 3D7-DBL1X-6ε and immobilized placental CSPG, the variation in the steady-state SPR signal as a function of protein concentration was used to calculate the dissociation constant KD. The kinetic association curves used to derive KD are shown in the insert. Protein concentrations ranged from 20 nM to 1,280 nM. The KD constants of the other proteins were determined in the same way (Table 3).

Table 3.

KD for recombinant proteins binding to placental CSPG

| Protein | KD (µM) |

| DBL3X | 344 ± 27 |

| DBL6ε | 92 ± 13 |

| DBL4ε-6ε | 7.6 ± 1.5 |

| DBL1X-6ε | 0.061 ± 0.009 |

Recombinant 3D7-DBL1X-6ε Can Competitively Inhibit Parasite Binding to Decorin.

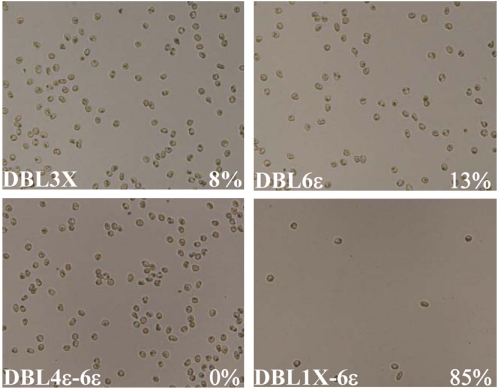

FCR3-CSA PE are known to bind specifically to CSA (25). Since our direct ELISA and SPR measurements showed that 3D7-DBL1X-6ε binds specifically to CSA, we determined its capacity to inhibit the binding of FCR3-CSA PE to decorin using a competition assay. Decorin-coated plates were incubated with each recombinant DBL domain prior to incubation with FCR3-CSA PE. Of the four proteins, parasite binding to decorin was strongly inhibited only by 3D7-DBL1X-6ε (85%); equivalent masses of the single domains and 3D7-DBL4ε-6ε inhibited by 13% or less (Fig. 5). FCR3-CD36 parasites, used as negative control, did not bind to CSA. These data clearly show that only the recombinant 3D7-DBL1X-6ε is fully functional and mimics the native adhesin present on the PE surface.

Fig. 5.

3D7-DBL1X-6ε inhibits PE adhesion. Recombinant proteins DBL3X, DBL6ε, DBL4ε-6ε and DBL1X-6ε (0.2 mg/mL in PBS) were incubated on decorin-coated spots prior to addition of FCR3-CSA PE. Bound parasites were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde and were counted to measure percentage inhibition. Percentage inhibition is indicated for each individual protein in the bottom right corner.

Discussion

The large molecular weight and high cysteine content of the full-length extracellular region of var2CSA have so far hindered its expression in heterologous systems, restricting functional and structural studies to single recombinant domains. Previous studies have shown that var2CSA contains several domains that bind CSA (9, 23, 24) but more recent results indicate that these soluble modules show poor specificity as they also bind to other sulfated sugars (25, 30). The data presented here, obtained with the full-length DBL1X-6ε extracellular region from the 3D7 parasite strain expressed in HEK 293 cells, clearly indicate that this protein binds with high affinity and specificity to CSA (KD = 61 nM), while single domains bind with much lower affinity, with a KD greater than 100 μM, confirming recently published data (30). The CSA-binding constants for single and multiple domains measured in our study do not in themselves permit a distinction between an overall affinity of 3D7-DBL1X-6ε for CSA as a product of independent affinities of the individual domains (i.e., an avidity effect), or the formation of a high-affinity binding site resulting from a higher-order structure of the full-length protein. Nonetheless, the contrast between the exquisite specificity for CSA shown here for 3D7-DBL1X-6ε and the promiscuous binding of sulfated GAG by single domains reported elsewhere (25, 30), strongly argues for the formation of a specific, high-affinity CSA-binding site created from a structured organization of the full-length extracellular region via well defined interdomain interactions. Indeed, combining our results with those recently reported, showing an absence of CSA-binding for FCR3-DBL4ε (25) but a strong inhibition of PE binding to CSA in the presence of anti-DBL4ε antibodies (20), suggests that this var2CSA domain does not participate directly in receptor binding but rather contributes to the structuring of the complete extracellular region; thus antibodies that disrupt interdomain interactions would disturb the higher-order structure necessary for the integrity of the CSA-binding site. The lack of specificity towards sulfated GAG found for single var2CSA domains could be due to the high isoelectric point of the lysine-rich DBL domains, which could lead to nonspecific electrostatic interactions with sulfated sugars, as reported for individual var2CSA and non-var2CSA DBL domains (25, 30).

The low-resolution structural results from AUC and SAXS are coherent with the hypothesis that CSA binding is dependent on a well defined overall structure of the extracellular region of var2CSA, since they indicate a compact organization of 3D7-DBL1X-6ε. Indeed, they clearly rule out an extended “beads on a string” structure where individual domains would behave independently of each other. AUC confirmed that 3D7-DBL1X-6ε was predominantly monomeric in solution and does not oligomerize to form a quaternary structure, but we cannot exclude the possibility that association between the extracellular region and other partner proteins occurs on the PE surface. Although recent proteomic and microarray analyses have revealed the presence of other P. falciparum proteins specifically expressed in placental and CSA-binding parasites (11, 12), there is no clear evidence that these proteins are exposed on the erythrocyte surface and involved in CSA adhesion. These proteins could be either involved in the trafficking of var2CSA to the PE surface or in its stabilization in a functional orientation through the formation of multiprotein complexes.

In conclusion, we provide here a unique demonstration of a binding phenotype that is associated with the multidomain organization of PfEMP1 and not with only one domain, such as the well characterized CIDR1α/CD36 and DBLβC2/ICAM-1 interactions (6). Moreover, our results are in line with a previous study reporting interactions between different domains of PfEMP1 that modulate the adhesion phenotype of PE (31). Our observations could also explain why var2CSA gene orthologues present in different P. falciparum strains are more conserved than any other var genes in terms of sequence homology and domain organization. This study offers a first glimpse into the structural basis of PE binding to CSA and opens the way for further characterization of the receptor-binding site, which is a major target of the transcendent inhibitory maternal antibody response. The findings reported here have important implications for the development of an effective pregnancy-associated malaria vaccine and unique therapeutic strategies and could also open avenues into functional studies of other large and cysteine-rich virulence factors involved in malaria parasites sequestration and invasion.

Material and Methods

Recombinant Protein Expression and Purification.

Synthetic genes were designed for 3D7-DBL4ε-6ε and 3D7-DBL1X-6ε (accession PFL0030c) with optimized codons for human expression. These were cloned into a pTT3 vector with an N-terminal murine Ig κ-chain leader sequence and a hexa-His C-terminal tag. Since P. falciparum proteins are not N-glycosylated, all serines or threonines at potential N-glycosylation sites were substituted by alanine in the synthetic genes (Table S1). FreeStyle 293-F cells (Invitrogen) were grown in Freestyle 293 serum-free expression medium and transfected with the pTT3 vector containing the appropriate gene as previously described (19). Cells were centrifuged 96 h posttransfection and the culture medium was harvested, filtered on a 0.22 μm filter and the supernatants concentrated five times using a 10 kDa cut-off Vivaflow 200 System (Vivasciences). Both proteins were purified on a HisTrap Fast Flow Ni-affinity column (GE Healthcare). 3D7-DBL1X-6ε was further purified by ion exchange chromatography on an SP Sepharose column (GE Healthcare) by elution with 1 M NaCl in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.8. Both proteins were subjected to gel filtration chromatography on a Superde column (GE Healthcare) as the final purification step and concentrated using Macro- and Microsep concentrators (Pall/Millipore). Protein concentrations were determined with the BioRad protein estimation kit and the purity of the samples was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot. Expression and purification of FCR3-DBL3X and FCR3-DBL6ε in E. coli are given as SI Text.

column (GE Healthcare) as the final purification step and concentrated using Macro- and Microsep concentrators (Pall/Millipore). Protein concentrations were determined with the BioRad protein estimation kit and the purity of the samples was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot. Expression and purification of FCR3-DBL3X and FCR3-DBL6ε in E. coli are given as SI Text.

Circular Dichroism.

CD spectra were measured on an Aviv215 spectropolarimeter equipped with a Peltier thermostated cell holder (Aviv Biomedical). All recombinant proteins were dialyzed against 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 0.25 M NaF, pH 6.8. Details of measurements and data analysis are given as SI Text.

Surface Plasmon Resonance.

Interaction between the recombinant proteins in solution and human placental CSPG (MR4 Reagents Resource), covalently coupled to a CM5 sensor chip (GE Healthcare) via its protein moiety, was studied on a Biacore® 2000 SPR system (GE Healthcare). KD was determined from the concentration-dependence of steady-state SPR response (after corrections for nonspecific binding). Further experimental details are reported as SI Text.

AUC and SAXS Analysis.

Sedimentation velocity experiments were performed at 20 °C on a ProteomeLab XL-I ultracentrifuge (Beckman-Coulter). Data analysis was performed by continuous size distribution analysis c(s) using the program Sedfit 11.2 (32).

SAXS data were collected at the BioSAXS station (ID14EH3) at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF), a fixed energy beamline optimized for solution scattering from biological macromolecules (13.32 keV, λ = 0.931 Å). Scattered intensity distributions were radially averaged and corrected by subtraction of buffer scattering using PRIMUS (33) from the ATSAS program package. Normalized curves were used to determine the model-independent scattering parameters: Rg, estimated molecular mass, particle volume and Dmax. Multiple runs of ab initio modeling done with DAMMIF (34) were evaluated with DAMAVER (34) and the theoretical scattering for the extended model was fitted to the merged scattering curve using the program CRYSOL (35). The program SASREF (36) was employed for rigid-body fitting to experimental data using the extended model (Fig. 2C) as a starting point. Further details of the AUC and SAXS analyses are given as SI Text.

ELISA of Var2CSA Protein Binding to Different Glycosaminoglycans.

ELISA plates were coated with different GAG: 5 μg/mL for decorin (Sigma, D8428); 50 μg/mL for chondroitin sulphate A (CSA) (Sigma, C8529), chondroitin sulphate C (CSC) (Seikagaku, 400670) and heparan sulphate (HS) (Sigma, H7640) in PBS (Gibco, NaCl 155 mM pH 7.2), using 100 μL per well overnight at 4 °C. BSA at 1% in PBS was taken for background measurement. After coating, the wells were blocked with 150 μL of dilution buffer per well (PBS 1% BSA, 0.05% Tween20) for 1 h at 37 °C. After removal of the blocking solution, each recombinant protein (FCR3-DBL3X, FCR3-DBL6ε, 3D7-DBL4ε-6ε, and 3D7-DBL1X-6ε) at serial dilutions of 0.3125–20 μg/mL in the dilution buffer, was added per well and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with gentle shaking. After washing three times with PBST (PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20), 100 μL antiHis HRP conjugated antibody (diluted 1∶2000 in dilution buffer) was added to each well and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. After washing three times with PBST, the interaction was estimated with TMB (3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine) substrate (Biorad) using 100 μL per well for 20 min or until saturation was reached. Absorbance was measured at 655 nm.

Inhibition of CSA Binding to Recombinant Domains.

Inhibition assays were performed using a similar protocol to that described above for ELISA, with decorin or CSA coated on the plate. Recombinant proteins at a concentration of 1 μg/mL were premixed with increasing amounts of decorin, CSA, CSC, or HS (0.156–100 μg/mL) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with gentle shaking before addition to the coated ELISA plate.

Parasite Culture.

P. falciparum FCR3-CSA and FCR-CD36 strains were maintained in culture under standard conditions in O+ human erythrocytes in RPMI 1640 containing L-glutamine (Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% Albumax I, 1 × hypoxanthine and 20 μg/mL gentamicin (37). Cultures were routinely selected by gelatin flotation using Plasmion (Fresenius Kabi) to maintain knob-positive parasites (38). CD36 or CSA-binding PE phenotypes were verified on receptors immobilized on plastic Petri dishes as previously described (39). Parasites were tested mycoplasma negative by PCR. Synchronous PE cultures (3–12% parasitaemia) at mid/late trophozoite stages were purified using the VarioMACS and CS columns (Miltenyi) as previously described (40).

Inhibition of PE Binding by Recombinant Proteins.

Petri dishes (Falcon) were coated with 10 μL of ligand (1 mg/mL CSA, 1% BSA, 45 μg/mL CD36, 50 μg/mL decorin) diluted in PBS within ∼0.5 cm diameter circles and incubated overnight at 4 °C in a humid chamber. Each spot was washed three times with PBS and subsequently blocked with 1% BSA in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking, 10 μL of recombinant proteins at 0.2 mg/mL in PBS were added to the spots and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After removal of recombinant protein, 10 μL PE previously purified with VarioMACS and CS columns (Miltenyi) were added to each spot at the concentration of 5 × 107 PE/mL. After incubation for 1 h at room temperature each spot was gently washed 3–5 times with PBS. Parasites bound to the spot were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde in PBS and were counted to measure percentage of inhibition.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank the staff at the ESRF, Grenoble, for access to the synchrotron facility. We thank Dr Y. Durocher for providing the pTT3 vector, T. Ramdani for assistance in protein production, Pr. C. Gowda for providing placental CSPG through the MR4 Reagents Resource and Dr. M. Higgins for kindly supplying the plasmid for expression of FCR3-DBL3X. The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme Grant ([FP7/2007-2013]) (to G.A.B. and B.G.) under Grant agreement 201222.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/1000951107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Brabin BJ, et al. The sick placenta-the role of malaria. Placenta. 2004;25(5):359–378. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fried M, Duffy PE. Adherence of Plasmodium falciparum to chondroitin sulfate A in the human placenta. Science. 1996;272(5267):1502–1504. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkhalil A, Achur RN, Valiyaveettil M, Ockenhouse CF, Gowda DC. Structural requirements for the adherence of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes to chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans of human placenta. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(51):40357–40364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006399200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salanti A, et al. Evidence for the involvement of VAR2CSA in pregnancy-associated malaria. J Exp Med. 2004;200(9):1197–1203. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salanti A, et al. Selective upregulation of a single distinctly structured var gene in chondroitin sulphate A-adhering Plasmodium falciparum involved in pregnancy-associated malaria. Mol Microbiol. 2003;49(1):179–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kraemer SM, Smith JD. A family affair: var genes, PfEMP1 binding, and malaria disease. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9(4):374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bockhorst J, et al. Structural polymorphism and diversifying selection on the pregnancy malaria vaccine candidate VAR2CSA. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;155(2):103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffy MF, et al. Transcribed var genes associated with placental malaria in Malawian women. Infect Immun. 2006;74(8):4875–4883. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01978-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gamain B, et al. Identification of multiple ChondroitinSulfate A (CSA)-binding domains in the var2CSA gene transcribed in CSA-binding parasites. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(6):1010–1013. doi: 10.1086/428137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuikue Ndam NG, et al. High level of var2csa transcription by Plasmodium falciparum isolated from the placenta. J Infect Dis. 2005;192(2):331–335. doi: 10.1086/430933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis SE, et al. Six genes are preferentially transcribed by the circulating and sequestered forms of Plasmodium falciparum parasites that infect pregnant women. Infect Immun. 2007;75(10):4838–4850. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00635-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fried M, et al. The distinct proteome of placental malaria parasites. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;155(1):57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Viebig NK, et al. A single member of the Plasmodium falciparum var multigene family determines cytoadhesion to the placental receptor chondroitin sulphate A. EMBO Rep. 2005;6(8):775–781. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Viebig NK, et al. Disruption of var2csa gene impairs placental malaria associated adhesion phenotype. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(9):e910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duffy MF, et al. VAR2CSA is the principal ligand for chondroitin sulfate A in two allogeneic isolates of Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2006;148(2):117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duffy PE, Fried M. Antibodies that inhibit Plasmodium falciparum adhesion to chondroitin sulfate A are associated with increased birth weight and the gestational age of newborns. Infect Immun. 2003;71(11):6620–6623. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.11.6620-6623.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fried M, Nosten F, Brockman A, Brabin BJ, Duffy PE. Maternal antibodies block malaria. Nature. 1998;395(6705):851–852. doi: 10.1038/27570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ricke CH, et al. Plasma antibodies from malaria-exposed pregnant women recognize variant surface antigens on Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes in a parity-dependent manner and block parasite adhesion to chondroitin sulfate A. J Immunol. 2000;165(6):3309–3316. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernandez P, et al. Var2CSA DBL6-epsilon domain expressed in HEK293 induces limited cross-reactive and blocking antibodies to CSA binding parasites. Malaria J. 2008;7:170. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nielsen MA, et al. Induction of adhesion-inhibitory antibodies against placental Plasmodium falciparum parasites by using single domains of VAR2CSA. Infect Immun. 2009;77(6):2482–2487. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00159-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guitard J, et al. Differential evolution of anti-VAR2CSA- IgG3 in primigravidae and multigravidae pregnant women infected by Plasmodium falciparum. Malaria J. 2008;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tuikue Ndam NG, et al. Dynamics of anti-VAR2CSA immunoglobulin G response in a cohort of senegalese pregnant women. J Infect Dis. 2006;193(5):713–720. doi: 10.1086/500146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avril M, et al. Characterization of anti-var2CSA-PfEMP1 cytoadhesion inhibitory mouse monoclonal antibodies. Microbes Infect. 2006;8(14–15):2863–2871. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bir N, et al. Immunogenicity of Duffy binding-like domains that bind chondroitin sulfate A and protection against pregnancy-associated malaria. Infect Immun. 2006;74(10):5955–5963. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00481-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Resende M, et al. Chondroitin sulphate A (CSA)-binding of single recombinant Duffy-binding-like domains is not restricted to Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 expressed by CSA-binding parasites. International Journal of Parasitology. 2009;39(11):1195–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh SK, Hora R, Belrhali H, Chitnis CE, Sharma A. Structural basis for Duffy recognition by the malaria parasite Duffy-binding-like domain. Nature. 2006;439(7077):741–744. doi: 10.1038/nature04443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tolia NH, Enemark EJ, Sim BK, Joshua-Tor L. Structural basis for the EBA-175 erythrocyte invasion pathway of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Cell. 2005;122(2):183–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins MK. The structure of a chondroitin sulfate-binding domain important in placental malaria. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(32):21842–21846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C800086200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh K, et al. Structure of the DBL3x domain of pregnancy-associated malaria protein VAR2CSA complexed with chondroitin sulfate A. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15(9):932–938. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khunrae P, Philip JM, Bull DR, Higgins MK. Structural comparison of two CSPG-binding DBL domains from the VAR2CSA protein important in malaria during pregnancy. J Mol Biol. 2009;393(1):202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gamain B, Gratepanche S, Miller LH, Baruch DI. Molecular basis for the dichotomy in Plasmodium falciparum adhesion to CD36 and chondroitin sulfate A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(15):10020–10024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152321599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schuck P. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and lamm equation modeling. Biophys J. 2000;78(3):1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konarev PV, Volkov VV, Sokolova AV, Koch MHJ, Svergun DI. PRIMUS: a Windows PC-based system for small-angle scattering data analysis. J Appl Crystallogr. 2003;36:1277–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franke D, Svergun DI. Dammif, a program for rapid ab initio shape determination in small angle scattering. J Appl Crystallogr. 2009;42:342–346. doi: 10.1107/S0021889809000338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Svergun D, Barberato C, Koch MHJ. CRYSOL—a program to evaluate x-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. J Appl Crystallogr. 1995;28:768–773. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petoukhov MV, Svergun DI. Global rigid body modeling of macromolecular complexes against small-angle scattering data. Biophys J. 2005;89(2):1237–1250. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.064154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trager W, Jensen JB. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193(4254):673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lelievre J, Berry A, Benoit-Vical F. An alternative method for Plasmodium culture synchronization. Exp Parasitol. 2005;109(3):195–197. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Viebig NK, Nunes MC, Scherf A, Gamain B. The human placental derived BeWo cell line: A useful model for selecting Plasmodium falciparum CSA-binding parasites. Exp Parasitol. 2006;112(2):121–125. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Staalsoe T, Giha HA, Dodoo D, Theander TG, Hviid L. Detection of antibodies to variant antigens on Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes by flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1999;35(4):329–336. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19990401)35:4<329::aid-cyto5>3.3.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.