Abstract

The perifornical-lateral hypothalamic area (PF-LHA) plays a central role in the regulation of behavioral arousal. The PF-LHA contains several neuronal types including wake-active hypocretin (HCRT) neurons that have been implicated in the promotion and/or maintenance of behavioral arousal. Adenosine is an endogenous sleep factor and recent evidence suggests that activation and blockade of adenosine A1 receptors within the PF-LHA promote and suppress sleep, respectively. Although, an in vitro study indicates that adenosine inhibits HCRT neurons via A1 receptor, the in vivo effects of A1 receptor mediated adenosinergic transmission on PF-LHA neurons including HCRT neurons are not known. First, we determined the effects of N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA), an adenosine A1 receptor agonist, on the sleep-wake discharge activity of the PF-LHA neurons recorded via microwires placed adjacent to the microdialysis probe used for its delivery. Second, we determined the effects of CPA and that of an A1 receptor antagonist, 1,3-dipropyl-8-phenylxanthine (CPDX) into the PF-LHA on cFos-protein immunoreactivity (Fos-IR) in HCRT and non-HCRT neurons around the microdialysis probe used for their delivery. The effect of CPA was studied in rats that were kept awake during lights-off phase, whereas the effect of CPDX was examined in undisturbed rats during lights-on phase. CPA significantly suppressed the sleep-wake discharge activity of PF-LHA neurons. Doses of CPA (50μM) and CPDX (50μM) that suppressed and induced arousal, respectively, in our earlier study (Alam et al., 2009), significantly suppressed and increased Fos-IR in HCRT and non-HCRT neurons. These findings suggest that wake-promoting PF-LHA system is subject to increased endogenous adenosinergic inhibition and that adenosine acting via A1 receptors, in part, inhibits HCRT neurons to promote sleep.

Keywords: Perifornical-lateral hypothalamus; Posterior-lateral hypothalamus; Adenosine, Orexin; Adenosine A1 receptor; Sleep

INTRODUCTION

Much evidence supports that the perifornical-lateral hypothalamic area (PF-LHA) plays a central role in the regulation of behavioral arousal and locomotor activity(Gerashchenko and Shiromani, 2004, Datta and Maclean, 2007, McCarley, 2007, Szymusiak and McGinty, 2008). Stimulation of the PF-LHA evokes locomotor activity, EEG activation, and arousal (Stock et al., 1981, Sinnamon et al., 1999, Alam and Mallick, 2008). The PF-LHA predominantly contains neurons that discharge with cortical activation, i.e., during waking or during both waking and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and are quiescent during nonREM sleep, although other neuronal phenotypes have also been identified (Alam et al., 2002, Koyama et al., 2003, Suntsova et al., 2007). Neurochemically, the PF-LHA contains a heterogeneous population of neurons, including those expressing hypocretin (HCRT), melanin-concentrating hormone (MCH), gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and glutamate (Bittencourt et al., 1992, Peyron et al., 1998, Abrahamson and Moore, 2001, Gerashchenko and Shiromani, 2004, Ohno and Sakurai, 2008). Amongst these neuronal groups, HCRT neurons in particular have been extensively studied and have been implicated in the facilitation and/or maintenance of arousal (Nishino, 2007, Ohno and Sakurai, 2008). These neurons exhibit wake-associated discharge and c-Fos expression (Fos-IR) and are quiescent during both nonREM and REM sleep (Estabrooke et al., 2001, Espana et al., 2003, Alam et al., 2005, Lee et al., 2005, Mileykovskiy et al., 2005). Local applications of HCRT into various projection targets promote waking (Bourgin et al., 2000, Methippara et al., 2000, Thakkar et al., 2001). A loss of HCRT signaling is linked with the pathogenesis of narcolepsy in human and animals (Lin et al., 1999, Peyron et al., 2000, Thannickal et al., 2000, Nishino, 2007, Ohno and Sakurai, 2008, Anaclet et al., 2009). Although, mostly in vitro studies have identified several neurotransmitters and neuromodulators that influence the activity of HCRT neurons (Kukkonen et al., 2002, Goutagny et al., 2005, Ohno and Sakurai, 2008), the neurotransmitter(s) or the mechanism(s) that regulate the suppression of HCRT and other PF-LHA neurons during sleep remains poorly understood.

Adenosine is a ubiquitous neuromodulator and various lines of studies support its role as an endogenous sleep factor (Benington and Heller, 1995, Dunwiddie and Masino, 2001, Basheer et al., 2004, Datta and Maclean, 2007, McCarley, 2007, Scharf et al., 2008). The production of adenosine is coupled with the metabolic activity, which is higher during waking as compared with sleep (Maquet, 1995, Porkka-Heiskanen et al., 1997). Adenosine or its agonists promote sleep and increase EEG slow wave activity, whereas, its antagonists suppress sleep (Radulovacki et al., 1984, Benington et al., 1995, Landolt et al., 1995, Bennett and Semba, 1998, Methippara et al., 2005). Of known adenosinergic receptors, viz., A1, A2A, A2B and A3, both A1 and A2A receptors have been implicated in mediating the sleep-promoting effects of adenosine. Evidence suggests that adenosine-induced sleep is site and receptor dependent (Methippara et al., 2005).

Some evidence shows that adenosine acting via A1 receptor inhibits HCRT neurons. Microinjection or perfusion of adenosine A1 receptor antagonist into the PF-LHA produce arousal and suppress nonREM and REM sleep, whereas perfusion of A1 receptor agonist into the PF-LHA suppress arousal and produce nonREM and REM sleep (Thakkar et al., 2008, Alam et al., 2009). Adenosine A1 receptors are localized on HCRT neurons (Thakkar et al., 2002). An in vitro study indicates that adenosine inhibits HCRT neurons and that this effects is mediated via A1 receptors (Liu and Gao, 2007). However, the effects of A1 receptor activation or blockage on HCRT and other PF-LHA neurons in freely behaving animals remain unknown.

First, we examined transient effects of A1 receptor agonist on the extracellular activity of the PF-LHA neurons recorded via microwires placed adjacent to the microdialysis probe used for its delivery. We further determined the effects of unilateral perfusion, using reverse microdialysis, of adenosine A1 receptor agonist and antagonist into the PF-LHA on Fos-IR in HCRT vs. other PF-LHA neurons in freely behaving rats.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Experiments were performed on 34 Sprague-Dawley male rats, weighing between 250-350g. These rats were maintained on 12:12h light:dark cycle (lights on at 8.00 A.M.) and with food and water available ad libitum. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Veterans Affairs Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System's Institutional Animal Research Committee.

A. Surgical implantations

The experimental procedures used in this study have been described earlier in detail (Alam et al., 1999, Alam et al., 2005). In brief, under surgical anesthesia (Ketamine + Xylazine: 80:10 mg/kg; i.p.) and aseptic conditions, for unit recording study, electroencephalogram (EEG) and electromyogram (EMG) electrodes were implanted for polygraphic determination of sleep-waking states. A microdrive-microdialysis guide cannula assembly, consisting of a single barrel mechanical microdrive and an adjacent guide cannula for microdialysis probe insertion, was implanted such that their tips rested 3mm above the dorsal aspect of the PF-LHA (A, −2.9 to −3.1; L, 1.4 to 1.6, H, 4.5 to −5.5 from bregma) (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). Five pairs of microwires, each consisting of two 20μm insulated stainless steel wires glued together except for 2.0 mm at the tip, were passed through the microdrive barrel such that their tips projected into the PF-LHA. For immunohistochemical study, rat was stereotaxically implanted with unilateral guide cannula (23 G stainless steel) such that its tip rested 3mm above the dorsal aspect of the PF-LHA and was blocked with a stylet.

B. Experimental protocol

Experiments were conducted after at least 10 days of recovery and acclimatization of rats with the recording environment. At least 24h before the experiment, the stylet of the microdialysis guide cannula was replaced by microdialysis probe (semi-permeable membrane tip length, 1mm; outer diameter, 0.22mm; molecular cut off size, 50kDa; Eicom, Japan), fixed with dental acrylic and flushed with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF; composition in mM, 145 NaCl, 2.7 KCl, 1.3 MgSO4, 1.2 CaCl2, and 2 Na2HPO4; pH, 7.2) at a flow rate of 2μl/min. The time taken by the aCSF solution to travel from the reservoir to the tips of the probes were precisely calculated.

1. Effects of adenosine A1 receptor agonist on the discharge activity of the PF-LHA neurons

In an initial study, the transient effects of A1 receptor agonist, N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CPA), on the discharge activity of PF-LHA neurons was studied in freely behaving rat to confirm an in vitro finding of A1 receptor mediated inhibitory effects of adenosine on HCRT neurons (Liu and Gao, 2007). This study was conducted during lights-on period so that the discharge profile of the neurons during aCSF and CPA perfusion could be easily characterized through 2-3 sleep-wake cycles. The placement of the microdialysis probe was such that it was adjacent to the microwires and the extracellular environment of the recorded neurons was within the estimated microdialysis area, ~500-700μm, of the semi-permeable membrane (Alam et al., 2005, Kumar et al., 2007). The microdialysis probe was fixed and microwires were advanced adjacent to the side of the exposed microdialysis membrane to minimize the tissue trauma and ensure maximum stability of the unit recording.

Individual action potentials were sorted from amplified raw signals using Spike 2 software (Cambridge Electronic Design 1401, London). First, the discharge rate of isolated PF-LHA neuron was recorded through 2-3 stable sleep-wake cycles during aCSF perfusion (baseline). After baseline recordings, 10μM CPA was perfused for 10min so that the acute effects of CPA on the state-dependent discharge activity of the PF-LHA neurons could be studied without triggering strong behavioral responses. After delivery of CPA the perfusion solution was switched back to aCSF and recordings continued for another 60-120 min or until the discharge rate returned to the baseline levels. During the entire recording session, rats were undisturbed except, if necessary, a stable episode of waking for 2-3 min was achieved by mild auditory stimuli or gentle touch. EEG, EMG, and raw microwire signals were digitized and stored on a disc for subsequent off-line analyses. The location of the microdialysis probe and the microwire tracts were histologically confirmed.

2. Effects of adenosine A1 receptor agonist/antagonist on Fos-IR in the PF-LHA neurons

Evidence suggests that maximum number of PF-LHA neurons exhibit active-waking associated Fos-IR (Estabrooke et al., 2001, Espana et al., 2003, Kumar et al., 2007) and that adenosine inhibits HCRT neurons in vitro (Liu and Gao, 2007). Therefore, to maximize the chances of observing the effects CPA on Fos-IR in HCRT and other PF-LHA neurons, this study was conducted in awake animals during lights-off period between 10.00 P.M. and 12.00 A.M. Three groups of rats were kept awake and moving for 2h by gently tapping on the recording cage and if necessary by gently touching them with a soft brush, while the PF-LHA was continuously perfused with aCSF (control), 5μM or 50μM CPA. The animals were kept awake to achieve maximum Fos-IR cell counts and also to avoid any indirect effects of behavioral state changes on Fos-IR that could result due to CPA perfusion (Alam et al., 2009). The two doses of CPA were selected based on our earlier studies of the effects of CPA perfusion into the PF-LHA on sleep-wakefulness (Alam et al., 2009).

In contrast, the effects of A1 receptor antagonist, 1,3-dipropyl-8-phenylxanthine (CPDX) on Fos-IR were determined in undisturbed animals during lights-on period between 10.00 A.M. and 12.00 P.M., when rats spend significantly more time asleep and fewer number of PF-LHA neurons express Fos-IR (Estabrooke et al., 2001, Espana et al., 2003, Alam et al., 2005). Two groups of rats were allowed to sleep normally, i.e., were undisturbed for 2 hrs while the PF-LHA was perfused with either control vehicle (0.1N NaOH, 125 times further diluted in aCSF) or 50 μM CPDX in the vehicle, a dose that was effective in inducing arousal (Alam et al., 2009). First, CPA and CPDX were dissolved in distilled water and 0.1N NaOH, respectively at mM concentrations and then the stock solutions were diluted to μM concentrations with aCSF for perfusion. The pH of the perfusing solution was adjusted to 7.2.

At the end of 2h, rats were given a lethal dose of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg), then injected with heparin (500U, i.p.), and perfused transcardially with 30-50ml of 0.1M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) followed by 500 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffer containing 15% saturated picric acid solution. The brains were removed and equilibrated in 10%, 20% and finally 30% sucrose. Frozen horizontal sections were cut at 30μm thickness. Alternate sections from the series of sections spanning the probe tract were immunostained for c-Fos and HCRT-1 proteins (Alam et al., 2005, Kumar et al., 2007). The experiments were conducted in pairs; tissues from one experimental and one control animal were processed together for immunostaining using the same batches of reagents and as described previously (Alam et al., 2005, Kumar et al., 2007).

a. c-Fos immunostaining

Sections through PF-LHA were first immunostained for c-Fos protein. Sections were incubated in rabbit anti-Fos antibody (1: 20,000 Calbiochem, California, USA) in diluent solution containing 4% goat serum and 0.2% triton in TBS for 40-48 hours at 4 °C. Sections were then incubated in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000 Vector Laboratories, California, USA) for 2 hours and incubated with avidin-biotin complex (ABC, 1:500, Vector Laboratories) for 2 hours. The sections were developed with nickel-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma, USA) for visualization that produced black reaction product confined to the nuclei. After staining for Fos-IR, sections were processed for HCRT-1 immunostaining.

b. HCRT-1 immunostaining

Sections were washed in TBS and then incubated in rabbit anti-HCRT-1 (orexin-A) antibody (1:1000, Calbiochem) for 40-48 hours at 4 °C. The sections were then incubated in biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500 Vector Laboratories) for 2 hours, followed by incubation in ABC (1:250, Vector Laboratories) for 2 hours and then developed with DAB producing a brown reaction product for visualization.

Two sections from each brain were treated as above except for the omission of the c-Fos or HCRT-1 primary antibody to control for nonspecific staining. Finally sections were rinsed in Tris (3 ×10 min) followed by TBS. The sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides, air-dried, dehydrated, and cover-slipped.

C. Data analyses

The sleep-wake discharge profiles of neurons were determined by the criteria adopted earlier (Alam et al., 2002). Neurons were classified as “wake-related” if their nonREM/active-wake as well as REM/active-wake discharge ratios were <0.5. Neurons were classified as “wake/REM-related” if REM/active-wake ratio was >0.5 and <1.5. Neurons were classified as “REM-related” if the REM/active-wake and REM/nonREM ratios were >1.5. The discharge rate in each behavioral state during baseline was compared with that during CPA perfusion using paired t-test.

A single person blind to the treatment conditions performed the counting and plotting of the immunoreactive neurons using the Neurolucida computer-aided plotting system (MicroBrightField). All sections were carefully reviewed and three representative sections about ~120 μm apart and encompassing the maximum number of HCRT+ neurons adjacent to the probe were considered for counting. The identification and counting of different neuronal types, i.e., single Fos+, HCRT+ or dual labeled HCRT+/Fos+ neurons were done manually. The Fos-IR was recognized by black stain localized to the nucleus, whereas brown-stained soma and dendrites was indicative of HCRT+ neurons. Neurons having a black nucleus and a brown cytoplasm were identified as HCRT+/Fos+ neurons (see figure-3)

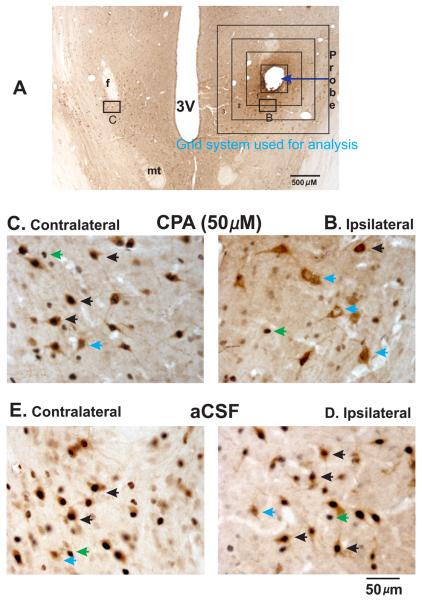

Figure-3. Effects of CPA on Fos-IR in PF-LHA neurons.

A. Photomicrograph of a horizontal section (40x magnification) from an animal that was kept awake for 2h while PF-LHA was perfused with 50μM CPA. The arrow indicates the location of the probe tract and the rectangular boxes around it show the grid system that was used for the quantification of Fos-IR in HCRT and non-HCRT neurons as a function of aCSF/vehicle or CPA/CPDX perfusions. The magnified images (400x) of the marked sections on the ipsilateral and contralateral sides are shown in figures B and C, respectively. The magnified images (400x) of the comparable ipsilateral and contralateral sections from an animal that was kept awake and perfused with aCSF for 2h are shown in D and E, respectively. A large number of HCRT+/Fos+ as well as HCRT−/Fos+ neurons can be seen on the ipsilateral side of aCSF treated as well as contralateral sides of both aCSF and CPA treated animals. As compared to aCSF control relatively fewer HCRT+/Fos+ and HCRT−/Fos+ neurons can be seen ipsilateral to CPA treatment. Blue arrowhead, HCRT+/Fos− neurons; green arrowhead, HCRT−/Fos+ neurons; black arrowhead, HCRT+/Fos+ neuron; f, fornix; mt, mammillothalamic tract; 3V, third ventricle.

In our earlier studies we found that the drugs perfused using the same delivery protocol affected neuronal population in ~500-750μm diameter field around the microdialysis probe (Alam et al., 2005, Kumar et al., 2007). Therefore, the area of interest (HCRT field) was marked as a 750μm rectangular box (750×750μm) that was placed at a distance of 50μm from the microdialysis membrane tract to avoid counting of damaged cells along the wall of the membrane. The 750×750μm area was further divided into three 250μm smaller consecutive grids/boxes (see figure-3) to determine if the effects of drugs on Fos-IR in PF-LHA neurons were dependent upon their diffusion gradients from the probe. The number of HCRT+ neurons in the box adjacent to the probe varied in different animals, depending upon the anatomical location of the probe. Therefore, percentage of HCRT+/Fos+ neurons vs. total number of HCRT+ neurons as a function of drug delivery was used to rectify this problem.

The numbers of single labeled Fos+, HCRT+, and double labeled HCRT+/Fos+ neurons in different grids after drug and control treatments were compared using one way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak test and t-test or Mann-Whitney rank test, in those cases where normality test failed.

RESULTS

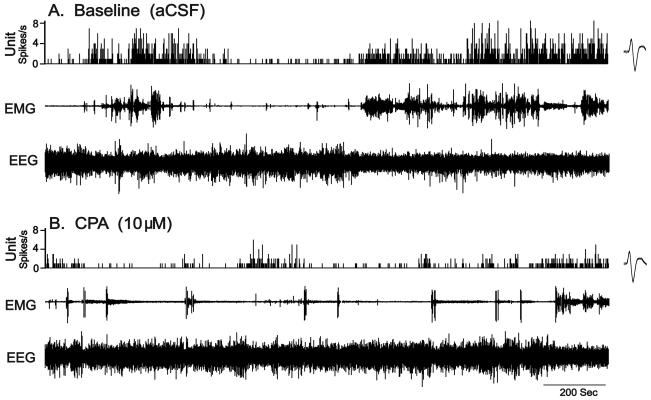

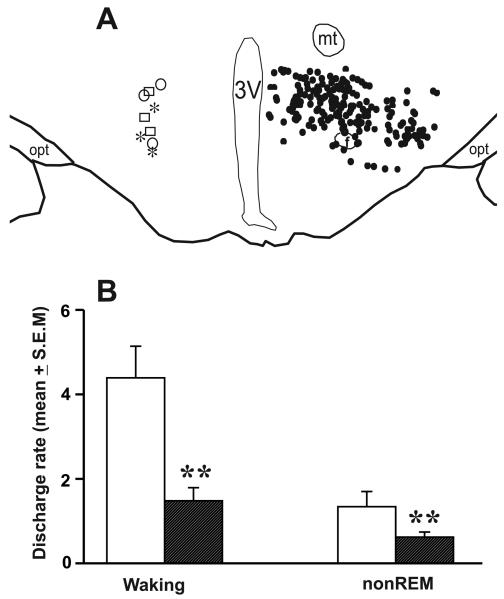

A. Effects of A1 receptor activation on the discharge activity of PF-LHA neurons

In order to evaluate if PF-LHA neurons are subject to A1 receptor mediated adenosinergic influences, in an initial study, 9 neurons along the dorsal to ventral passes through the PF-LHA were characterized in relation to their sleep-wake discharge profiles and the effects of 10μM CPA (figures 1 and 2). As regards their baseline sleep-wake discharge profiles, 6 neurons were moderately to strongly wake-active and 3 neurons were wake-REM active. 10μM CPA suppressed the discharge in 7 of 9 neurons by >25% including 4 of 6 wake-active neurons. The recorded neurons as a group exhibited significant suppression in their discharge in response to CPA during both waking and nonREM sleep. REM sleep was observed only in a few cases during the first 20-40min after CPA perfusion and therefore, the effects of CPA on REM discharge was not considered for analysis. The microdialysis perfusion of CPA suppressed the discharge activity of PF-LHA neurons while spike shape parameters, e.g., spike amplitude and waveform were unchanged (Figure-1).

Figure 1. Effects of CPA on the discharge activity of an individual PF-LHA neuron.

Thirty min continuous recordings showing the discharge rate of an individual wake-active neuron during aCSF (A) and in presence of 10μM CPA (point of injection not shown) delivered adjacent to the cell via reverse microdialysis (B). CPA was perfused for 10min. The action potentials on the side panels represent average waveform of the action potentials captured during 60s. EEG, electroencephalogram; EMG, electromyogram.

Figure 2. Effects of CPA on PF-LHA neurons.

A. Camera lucida drawing of a representative coronal section through the PF-LHA showing anatomical locations and sleep-wake profiles of the recorded neurons (left side; open circle, wake/REM related; open square, moderately wake-active; and star, strongly wake-active neurons) and the distribution of HCRT+ neurons (right side, filled circles). B. The effects of CPA on the mean discharge rate (±SEM) of PF-LHA neurons as a group during waking and nonREM sleep. **, p <0.01 (Student's paired t-test). f, fornix; mt, mammillothalamic tract; 3V, third ventricle.

B. Effects of A1 receptor activation/inactivation on Fos-IR in PF-LHA neurons

In order to determine whether A1 receptor mediated adenosinergic transmission in freely behaving animals inhibits HCRT neurons, the effects of CPA and CPDX perfusions were quantified on Fos-IR in HCRT+ vs. HCRT− (single Fos+) neurons.

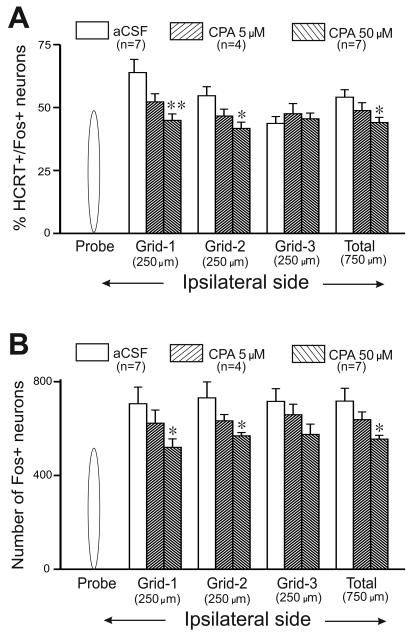

1. Effects of CPA on Fos-IR in HCRT neurons

The effects of aCSF (n=7) and that of CPA (5μM, n=4; and 50μM, n=7) on Fos-IR in HCRT+ neurons in rats that were kept awake during lights-off period are shown in figures 3-4. The number of HCRT+ neurons in aCSF and CPA treated rats around the microdialysis probe (436 ± 19 vs. 425 ± 15) were not significantly different. Consistent with earlier studies (Estabrooke et al., 2001, Alam et al., 2005, Kumar et al., 2007) in aCSF treated rats, relatively larger number of HCRT+ neurons exhibiting Fos-IR were observed around the microdialysis probe (Figure-3). In CPA-treated rats the percentage of HCRT+ neurons exhibiting Fos-IR around the microdialysis probe decreased significantly as compared to aCSF treated rats. The decrease in the percentage of HCRT+/Fos+ neurons in CPA treated rats showed a dose-dependent trend and CPA was most effective in ~500μM radius around the microdialysis probe (figure-4).

Figure-4. Effects of CPA on Fos-IR in HCRT and non-HCRT PF-LHA neurons.

Mean (±SEM) percentage of HCRT+/Fos+ neurons (A) and number of HCRT−/Fos+ neurons (B) in different grids adjacent to the microdialysis probe after aCSF and CPA perfusion in awake animals during lights-off period. In presence of CPA the number of HCRT+/Fos+ and HCRT/Fos+ neurons increased in a dose-dependent manner in 500-750μm area around the probe as compared to the aCSF treatment. **, < 0.01; *, <0.05 level of significance (Students t-test).

2. Effects of CPA on Fos-IR in non-HCRT neurons

The effects of aCSF and that of CPA on Fos-IR in non-HCRT neurons in rats that were kept awake during lights-off period are shown in figures 3-4. Consistent with earlier studies (Estabrooke et al., 2001, Espana et al., 2003, Alam et al., 2005, Kumar et al., 2007), a large number of single Fos-IR neurons were observed around the microdialysis probe in aCSF treated rats. In CPA treated rats, the number of single Fos-IR neurons decreased significantly as compared to that observed after aCSF treatment in a dose dependent manner.

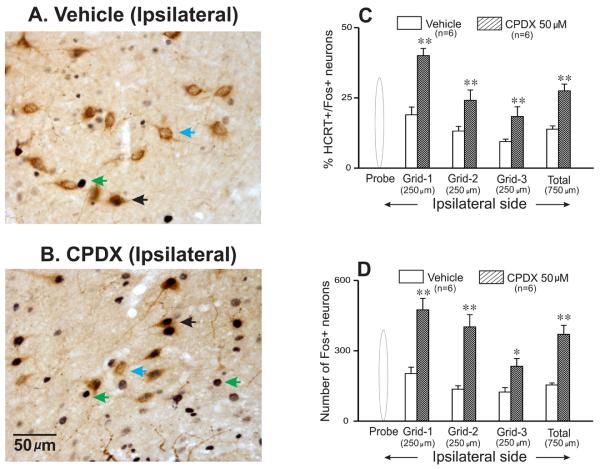

3. Effects of CPDX on Fos-IR in HCRT neurons

The effects of vehicle (n=6) and 50μM of CPDX (n=6) on Fos-IR in HCRT neurons during lights-on period in undisturbed animals are shown in figure-5. The number of HCRT+ neurons in control and CPDX treated rats around the microdialysis probe were comparable (322 ± 17 vs. 353 ± 7). Consistent with earlier studies (Estabrooke et al., 2001, Espana et al., 2003, Baldo et al., 2004, Alam et al., 2005), in control rats, few HCRT+/Fos+ neurons were observed around the microdialysis probe. However, as compared to control, in CPDX-treated rats the number of HCRT+/Fos+ neurons around the microdialysis probe increased significantly. The percentage of HCRT+/Fos+ neurons was highest in the grid that was closest to the probe and gradually decreased with increasing distance from the probe. The effect of CPDX was restricted to ~750μM radius from the probe.

Figure-5. Effects of CPDX on Fos-IR in PF-LHA neurons.

Photomicrographs (400x) showing Fos-IR in HCRT+ and HCRT− neurons adjacent to the microdialysis probe in vehicle (A) and CPDX (B) treated undisturbed animals. The mean (±SEM) percentage of HCRT+/Fos+ neurons and number of HCRT−/Fos+ neurons in different grids adjacent to the microdialysis probe in control and CPDX treated animals are shown in figures C and D, respectively. As compared to vehicle, in the presence of CPDX significantly larger numbers of HCRT and non-HCRT neurons expressed Fos-IR around the microdialysis probe. **, < 0.01; *, <0.05 level of significance (Students t-test). Blue arrowhead, HCRT+/Fos− neurons; green arrowhead, HCRT−/Fos+ neurons; black arrowhead, HCRT+/Fos+ neuron.

4. Effects of CPDX on Fos-IR in non-HCRT neurons

After perfusion of control solution during lights-on period, relatively few single Fos-IR neurons were found in different grids around the microdialysis probe (figure-5). In the presence of 50μM of CPDX in the PF-LHA, the number of single Fos+ neurons around the microdialysis probe increased significantly as compared to control rats.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that stimulation of adenosine A1-receptors in the PF-LHA by local perfusion of an agonist suppressed the discharge activity of PF-LHA neurons. A1 receptor stimulation also decreased the number of HCRT and non-HCRT wake-active neurons exhibiting Fos-IR around the microdialysis probe. On the other hand, during A1 receptor blockade, numbers of HCRT and non-HCRT neurons exhibiting Fos-IR in the diffusion field of the microdialysis probe increased significantly. These findings indicate a tonic inhibitory influence of adenosine via A1 receptor on PF-LHA neurons and support a hypothesis that adenosine within PF-LHA inhibits both HCRT and non-HCRT wake-active neurons to promote sleep.

This is the first study that has quantified the effects of focal activation and/or blockade of A1 receptor mediated adenosinergic transmission on HCRT and non-HCRT PH-LHA neuronal activities in freely behaving animals. We note: a) that although our sample of PF-LHA neurons was limited, adenosine A1 receptor agonist suppressed discharge activity of those neurons without affecting action potential amplitude or waveform (see figure-1); b) that the doses of A1 receptor agonist and antagonist that enhanced and suppressed sleep in an earlier study (Alam et al., 2009), inhibited and activated HCRT and other PF-LHA neurons, respectively; and c) that the drug delivery method used in this study reduced the likelihood that treatment effects could be due to mechanical or inflammatory responses (Quan and Blatteis, 1989). These observations argue that the effects observed in this study are physiological and that endogenous adenosine acting on A1 receptor influences HCRT and other PF-LHA neurons to modulate behavioral states.

The double label immunohistochemistry-microdialysis method permits scanning a large population of neurons in any given area for responsiveness to specific pharmacological agents along with their phenotypic characterization. However, since microdialysis provide a bathing medium for the entire extracellular environment of the studied neurons, the site of drug action cannot be pinpointed. The findings of this study that A1 receptor activation inhibited HCRT neurons confirms in an intact animals, an earlier in vitro finding that adenosine via A1 receptor exerts inhibitory influences on HCRT neurons (Liu and Gao, 2007). In addition, the findings of this study further indicate that A1 receptor mediated adenosinergic inhibition is not specific to HCRT neurons.

The PF-LHA plays a critical role in the regulation of behavioral arousal. The PF-LHA predominantly contains neurons that are active during cortical and behavioral arousal (see Introduction). The extracellular adenosine release has been linked with the metabolic state of the cell and it is likely that the activation of HCRT and other wake-active PF-LHA neurons during arousal contributes to the release and buildup of adenosine locally, which, in turn, as shown in this study, inhibits HCRT and non-HCRT wake-active PF-LHA neurons via A1 receptor to regulate sleep. That adenosine in the PF-LHA is involved in homeostatic sleep control is consistent with an in vivo microinjection study where A1 receptor antagonist during sleep deprivation attenuated recovery sleep (Thakkar et al., 2008).

The PF-LHA contains a heterogeneous population of several neuronal types including neurons expressing MCH, GABA and glutamate, as well as HCRT. Both MCH and GABAergic neurons have been implicated in the regulation of sleep, particularly REM sleep, whereas glutamate has been implicated in arousal and excitability of HCRT neurons (Liu et al., 2002, Kumar et al., 2007, Hassani et al., 2009, Peyron et al., 2009). Although in this study only HCRT neurons were characterized for Fos-IR, given that A1 receptor activation and inactivation in the PF-LHA suppressed and increased Fos-IR in non-HCRT neurons as well, it is possible that some of the non-HCRT neurons responding to A1 receptor agonist and antagonist were wake-active glutamatergic neurons. This interpretation is consistent with an earlier in vitro study suggesting that A1 receptor mediated inhibition of HCRT neurons most potently is mediated via presynaptic inhibition of the glutamatergic input (Liu and Gao, 2007). Furthermore, given the sleep promoting roles of MCH and GABAergic neurons within the PF-LHA, it is plausible that A1 receptor adenosinergic transmission has minimal effects on these neurons.

The A1 receptor agonist concentration that suppressed waking and induced nonREM/REM sleep after its perfusion into the PF-LHA in our earlier study (Alam et al., 2009), suppressed Fos-IR in HCRT and other PF-LHA neurons in this study. In contrast, the A1 receptor antagonist concentration that produced arousal and suppressed nonREM/REM sleep in our earlier study increased Fos-IR in HCRT and other PF-LHA neurons. It is likely that A1 receptor agonist and antagonist-induced sleep-wake changes in our earlier study were predominantly mediated via the neuronal population around the microdialysis probe that exhibited Fos-IR changes in response to A1 receptor stimulation and blockade in this study.

In conclusion, present study suggests that focal activation and blockade of adenosinergic transmission via A1 receptor inhibits and activates, respectively, HCRT and other wake-active PF-LHA neurons. Given the well-documented role of HCRT neurons in the behavioral arousal and sleep-promoting effects of adenosine within PF-LHA, these results support a hypothesis that wake-promoting PF-LHA system is subject to increased endogenous adenosinergic inhibition and that adenosine acting via A1 receptors in part inhibits HCRT neurons to promote sleep.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the US Department of Veteran Affairs Medical Research Service and US National Institutes of Health grants, NS-050939, MH63323, and MH075076.

ABBREVIATIONS

- aCSF

Artificial cerebrospinal fluid

- CPA

N6-cyclopentyladenosine, an A1 receptor agonist

- CPDX

1,3-dipropyl-8-phenylxanthine, an A1 receptor antagonist

- Fos-IR

c-fos protein immunoreactivity

- GABA

Gamma-aminobutyric acid

- HCRT

Hypocretin

- MCH

Melanin-concentrating hormone

- NonREM

Non-rapid eye movement sleep

- PF-LHA

Perifornical-lateral hypothalamic area

- TBS

Tris buffered saline

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

LITERATURE REFERENCES

- Abrahamson EE, Moore RY. The posterior hypothalamic area: chemoarchitecture and afferent connections. Brain Res. 2001;889:1–22. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MA, Mallick BN. Glutamic acid stimulation of the perifornical-lateral hypothalamic area promotes arousal and inhibits non-REM/REM sleep. Neurosci Lett. 2008;439:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MN, Gong H, Alam T, Jaganath R, McGinty D, Szymusiak R. Sleep-waking discharge patterns of neurons recorded in the rat perifornical lateral hypothalamic area. J Physiol. 2002;538:619–631. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.012888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MN, Kumar S, Bashir T, Suntsova N, Methippara MM, Szymusiak R, McGinty D. GABA-mediated control of hypocretin- but not melanin-concentrating hormone-immunoreactive neurones during sleep in rats. J Physiol. 2005;563:569–582. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.076927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MN, Kumar S, Rai S, Methippara M, Szymusiak R, McGinty D. Role of adenosine A(1) receptor in the perifornical-lateral hypothalamic area in sleep-wake regulation in rats. Brain Res. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.09.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam MN, Szymusiak R, Gong H, King J, McGinty D. Adenosinergic modulation of rat basal forebrain neurons during sleep and waking: neuronal recording with microdialysis. J Physiol. 1999;521(Pt 3):679–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.00679.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anaclet C, Parmentier R, Ouk K, Guidon G, Buda C, Sastre JP, Akaoka H, Sergeeva OA, Yanagisawa M, Ohtsu H, Franco P, Haas HL, Lin JS. Orexin/hypocretin and histamine: distinct roles in the control of wakefulness demonstrated using knock-out mouse models. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14423–14438. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2604-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldo BA, Gual-Bonilla L, Sijapati K, Daniel RA, Landry CF, Kelley AE. Activation of a subpopulation of orexin/hypocretin-containing hypothalamic neurons by GABAA receptor-mediated inhibition of the nucleus accumbens shell, but not by exposure to a novel environment. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:376–386. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basheer R, Strecker RE, Thakkar MM, McCarley RW. Adenosine and sleep-wake regulation. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;73:379–396. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benington JH, Heller HC. Restoration of brain energy metabolism as the function of sleep. Prog Neurobiol. 1995;45:347–360. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(94)00057-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benington JH, Kodali SK, Heller HC. Stimulation of A1 adenosine receptors mimics the electroencephalographic effects of sleep deprivation. Brain Res. 1995;692:79–85. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00590-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett HJ, Semba K. Immunohistochemical localization of caffeine-induced c-Fos protein expression in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1998;401:89–108. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19981109)401:1<89::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittencourt JC, Presse F, Arias C, Peto C, Vaughan J, Nahon JL, Vale W, Sawchenko PE. The melanin-concentrating hormone system of the rat brain: an immuno- and hybridization histochemical characterization. J Comp Neurol. 1992;319:218–245. doi: 10.1002/cne.903190204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgin P, Huitron-Resendiz S, Spier AD, Fabre V, Morte B, Criado JR, Sutcliffe JG, Henriksen SJ, de Lecea L. Hypocretin-1 modulates rapid eye movement sleep through activation of locus coeruleus neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7760–7765. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07760.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, Maclean RR. Neurobiological mechanisms for the regulation of mammalian sleep-wake behavior: reinterpretation of historical evidence and inclusion of contemporary cellular and molecular evidence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:775–824. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunwiddie TV, Masino SA. The role and regulation of adenosine in the central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:31–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espana RA, Valentino RJ, Berridge CW. Fos immunoreactivity in hypocretin-synthesizing and hypocretin-1 receptor-expressing neurons: effects of diurnal and nocturnal spontaneous waking, stress and hypocretin-1 administration. Neuroscience. 2003;121:201–217. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooke IV, McCarthy MT, Ko E, Chou TC, Chemelli RM, Yanagisawa M, Saper CB, Scammell TE. Fos expression in orexin neurons varies with behavioral state. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1656–1662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01656.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerashchenko D, Shiromani PJ. Different neuronal phenotypes in the lateral hypothalamus and their role in sleep and wakefulness. Mol Neurobiol. 2004;29:41–59. doi: 10.1385/MN:29:1:41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goutagny R, Luppi PH, Salvert D, Gervasoni D, Fort P. GABAergic control of hypothalamic melanin-concentrating hormone-containing neurons across the sleep-waking cycle. Neuroreport. 2005;16:1069–1073. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200507130-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassani OK, Lee MG, Jones BE. Melanin-concentrating hormone neurons discharge in a reciprocal manner to orexin neurons across the sleep-wake cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2418–2422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811400106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama Y, Takahashi K, Kodama T, Kayama Y. State-dependent activity of neurons in the perifornical hypothalamic area during sleep and waking. Neuroscience. 2003;119:1209–1219. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukkonen JP, Holmqvist T, Ammoun S, Akerman KE. Functions of the orexinergic/hypocretinergic system. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C1567–1591. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00055.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Szymusiak R, Bashir T, Rai S, McGinty D, Alam MN. Effects of serotonin on perifornical-lateral hypothalamic area neurons in rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:201–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landolt HP, Dijk DJ, Gaus SE, Borbely AA. Caffeine reduces low-frequency delta activity in the human sleep EEG. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1995;12:229–238. doi: 10.1016/0893-133X(94)00079-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Hassani OK, Jones BE. Discharge of identified orexin/hypocretin neurons across the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6716–6720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1887-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Faraco J, Li R, Kadotani H, Rogers W, Lin X, Qiu X, de Jong PJ, Nishino S, Mignot E. The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell. 1999;98:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu RJ, van den Pol AN, Aghajanian GK. Hypocretins (orexins) regulate serotonin neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus by excitatory direct and inhibitory indirect actions. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9453–9464. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09453.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZW, Gao XB. Adenosine inhibits activity of hypocretin/orexin neurons by the A1 receptor in the lateral hypothalamus: a possible sleep-promoting effect. J Neurophysiol. 2007;97:837–848. doi: 10.1152/jn.00873.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maquet P. Sleep function(s) and cerebral metabolism. Behav Brain Res. 1995;69:75–83. doi: 10.1016/0166-4328(95)00017-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarley RW. Neurobiology of REM and NREM sleep. Sleep Med. 2007;8:302–330. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methippara MM, Alam MN, Szymusiak R, McGinty D. Effects of lateral preoptic area application of orexin-A on sleep-wakefulness. Neuroreport. 2000;11:3423–3426. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200011090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methippara MM, Kumar S, Alam MN, Szymusiak R, McGinty D. Effects on sleep of microdialysis of adenosine A1 and A2a receptor analogs into the lateral preoptic area of rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1715–1723. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00247.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mileykovskiy BY, Kiyashchenko LI, Siegel JM. Behavioral correlates of activity in identified hypocretin/orexin neurons. Neuron. 2005;46:787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino S. The hypothalamic peptidergic system, hypocretin/orexin and vigilance control. Neuropeptides. 2007;41:117–133. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K, Sakurai T. Orexin neuronal circuitry: role in the regulation of sleep and wakefulness. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:70–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain: in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic Press. 1998 doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(80)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Faraco J, Rogers W, Ripley B, Overeem S, Charnay Y, Nevsimalova S, Aldrich M, Reynolds D, Albin R, Li R, Hungs M, Pedrazzoli M, Padigaru M, Kucherlapati M, Fan J, Maki R, Lammers GJ, Bouras C, Kucherlapati R, Nishino S, Mignot E. A mutation in a case of early onset narcolepsy and a generalized absence of hypocretin peptides in human narcoleptic brains. Nat Med. 2000;6:991–997. doi: 10.1038/79690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Sapin E, Leger L, Luppi PH, Fort P. Role of the melanin-concentrating hormone neuropeptide in sleep regulation. Peptides. 2009;30:2052–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porkka-Heiskanen T, Strecker RE, Thakkar M, Bjorkum AA, Greene RW, McCarley RW. Adenosine: a mediator of the sleep-inducing effects of prolonged wakefulness. Science. 1997;276:1265–1268. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5316.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quan N, Blatteis CM. Microdialysis: a system for localized drug delivery into the brain. Brain Res Bull. 1989;22:621–625. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(89)90080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovacki M, Virus RM, Djuricic-Nedelson M, Green RD. Adenosine analogs and sleep in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984;228:268–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf MT, Naidoo N, Zimmerman JE, Pack AI. The energy hypothesis of sleep revisited. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;86:264–280. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinnamon HM, Karvosky ME, Ilch CP. Locomotion and head scanning initiated by hypothalamic stimulation are inversely related. Behav Brain Res. 1999;99:219–229. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(98)00106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stock G, Rupprecht U, Stumpf H, Schlor KH. Cardiovascular changes during arousal elicited by stimulation of amygdala, hypothalamus and locus coeruleus. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1981;3:503–510. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(81)90083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suntsova N, Guzman-Marin R, Kumar S, Alam MN, Szymusiak R, McGinty D. The median preoptic nucleus reciprocally modulates activity of arousal-related and sleep-related neurons in the perifornical lateral hypothalamus. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1616–1630. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3498-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szymusiak R, McGinty D. Hypothalamic regulation of sleep and arousal. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129:275–286. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar MM, Engemann SC, Walsh KM, Sahota PK. Adenosine and the homeostatic control of sleep: effects of A1 receptor blockade in the perifornical lateral hypothalamus on sleep-wakefulness. Neuroscience. 2008;153:875–880. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar MM, Ramesh V, Strecker RE, McCarley RW. Microdialysis perfusion of orexin-A in the basal forebrain increases wakefulness in freely behaving rats. Arch Ital Biol. 2001;139:313–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar MM, Winston S, McCarley RW. Orexin neurons of the hypothalamus express adenosine A1 receptors. Brain Res. 2002;944:190–194. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02873-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thannickal TC, Moore RY, Nienhuis R, Ramanathan L, Gulyani S, Aldrich M, Cornford M, Siegel JM. Reduced number of hypocretin neurons in human narcolepsy. Neuron. 2000;27:469–474. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00058-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]