Abstract

The authors report the fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography(PET)/computed tomography (CT) findings of a rare case of growth hormone-secreting pituitary carcinoma with multiple metastatic lesions to the skeleton. A 31-year-old male had presented with acromegaly and had received transsphenoidal resection of a pituitary tumor and adjuvant radiotherapy. However, the tumor recurred with local invasions and the patient underwent more resections and adjuvant chemotherapy. Several months later, the patient developed rising levels of insulin-like growth factor 1 and whole-body FDG-PET/CT scanning revealed multiple hypermetabolic lesions throughout the skeleton compatible with metastasis.

Keywords: Pituitary carcinoma, metastasis, positron emission tomography/computed tomography

Introduction

Pituitary carcinomas are rare neoplasms distinguished from invasive adenomas by the presence of craniospinal and/or systemic metastases[1]. They represent approximately 0.2% of all operated adenohypophyseal neoplasms[2]. The histologic features of pituitary carcinomas vary from typical adenoma to tumor with marked pleomorphism and frequent mitoses[3]. The latency period between the presentation of a sellar adenoma and the manifestation of metastasis has a surprisingly wide range: from a few months to 18 years (median 5 years)[1,4]. Most pituitary carcinomas are hormonally active; the predominance of non-hormonally active carcinomas in the oldest series is probably attributed to the lack of hormonal assays and routine use of immunohistochemistry[4–6]. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) scanning have been used to detect pituitary pathology and to demonstrate metastases elsewhere. The utility of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/CT in the staging of pituitary carcinoma has not been reported to the best of our knowledge. We describe a 31-year-old patient with growth hormone-secreting pituitary carcinoma and multiple metastases to cervical, thoracic, lumbar spine, sternum, femur, and clavicles that were evident on PET/CT scan.

Case report

This 31-year-old man was diagnosed with a pituitary tumor in October 2002 with initial presentation of increased growth hormone and acromegaly. The patient underwent transsphenoidal resections in 2002 and 2003 followed by radiation therapy after the second resection. Furthermore, the patient underwent 2 further resections for local tumor recurrence in 2006 and 2007 with subsequent chemotherapy.

Histological examination after the initial surgery had showed marked nuclear pleomorphism and multinucleated tumor cells. Immunohistochemical techniques were strongly reactive for synaptophysin and showed high levels of growth hormone (GH)-specific cytoplasmic staining of the tumor cells but no significant immunoreactivity for prolactin, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) or luteinizing hormone (LH). The MIB-1 antibody labeled almost every nucleus of tumor cells.

In October 2006, MR imaging of the head and whole-body FDG-PET/CT showed local recurrence of tumor (Fig. 1A,B) which mandated surgical resection of the tumor. In December 2007, the IGF-1 level began to increase continuously and the patient underwent a complete workup. MR imaging of the brain and whole-body PET/CT did not show any evidence of local recurrence in the head. However, a suspicious lesion in the sacral area was found on whole-body FDG-PET/CT and confirmed on MR imaging (Fig. 2A,B). Subsequently the patient underwent local radiation therapy to sacral region and his IGF-1 levels decreased.

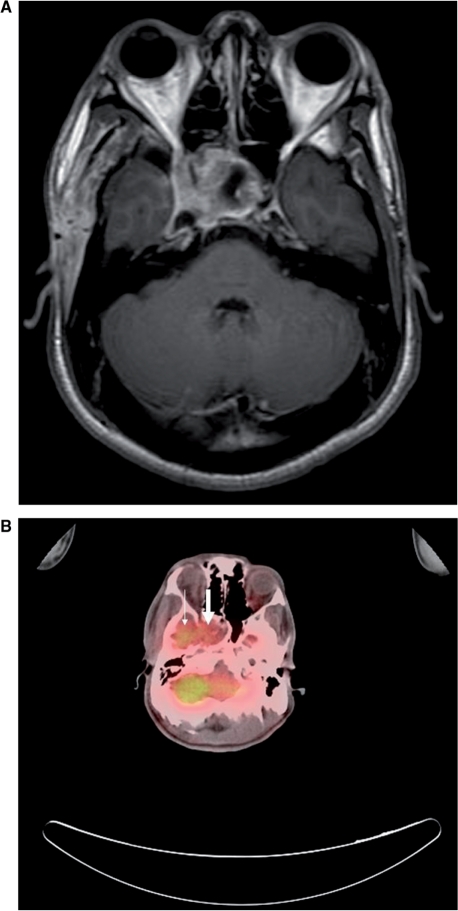

Figure 1.

(A) T1-weighted MR imaging (spin echo, repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE)=466.7 ms/13 ms) with contrast enhancement of the head shows an enhancing mass in the sella turcica extending to the right cavernous sinus, consistent with local recurrence of tumor. (B) Whole-body FDG-PET/CT fusion image in the same level shows abnormal increased FDG uptake of tumor (large arrow) and physiological uptake of right temporal lobe (small arrow).

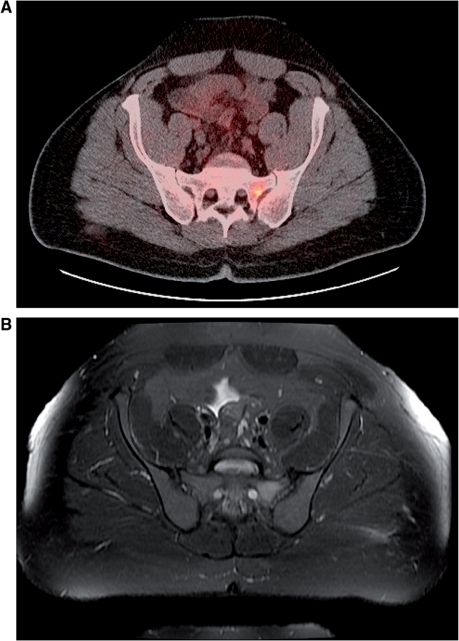

Figure 2.

(A) Whole-body FDG-PET/CT fusion image shows an area of increased FDG uptake in the left sacral ala, consistent with metastatic tumor. (B) The T2-weighted MR imaging (fast-spin echo, TR/TE/echo train length=5200 ms/72 ms/17) with fat saturation shows increased T2 signal intensity in the same area.

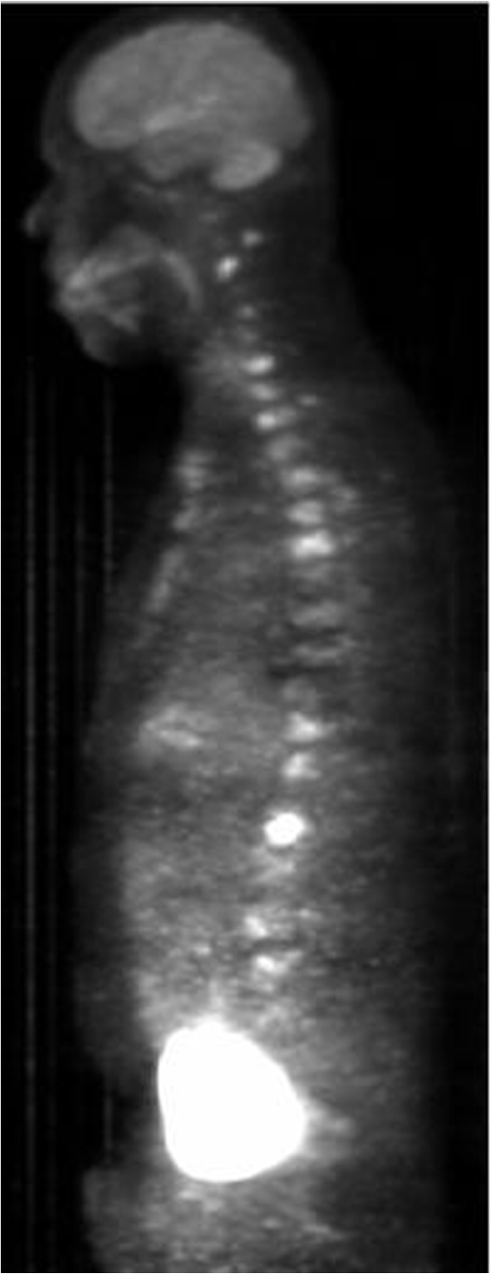

One year later, the patient was reinvestigated because of an increased level of IGF-1. At this time, the patient was free of new symptoms. A complete physical examination, including neurological examination, did not reveal new finding. A recent IGF-1 level was 1012 ng/ml; the most previous was 286 ng/ml. This abnormal laboratory finding prompted further evaluations including a MR scan and whole-body PET/CT scan. An MR study of the head showed a stable brain lesion compared with the previous study. At the same time, MR imaging of spine revealed an abnormal high T2 signal and enhancement in the S1 vertebra and in the left sacral ala that were consistent with previous findings 1 year previously. On FDG-PET/CT study, there were numerous foci of increased tracer uptake in the cervical, thoracic, lumbar spine, sternum, and bilateral proximal femur, compatible with metastatic disease (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

PET/CT maximum intensity projection image showing numerous foci of increased tracer uptake in the cervical, thoracic, lumbar spine, and sternum, consistent with metastatic disease.

Discussion

Pituitary carcinomas are rare adenohypophyseal neoplasms and their definition, diagnosis, therapy, and prognosis are controversial. Most of reported pituitary carcinomas are endocrinologically active, occurring with no sex dominance. In a review of the literature on pituitary carcinoma, Pernicone et al.[1] reported the endocrinological subtypes include prolactin-producing tumors (30%), ACTH-producing tumors (28%), GH-producing tumors (10%), TSH-producing tumors (2%), gonadotropin-producing tumors (2%), and non-functional tumors (26%). Unlike other malignant neoplasms, the diagnosis of pituitary carcinoma is based on metastasis and not on histologic features such as invasion, cellular pleomorphism, mitotic activity, and necrosis[7]. Excluding intracranial metastasis, the liver is the most frequent site of metastasis from pituitary carcinoma. Other sites of systemic metastasis include lungs, bones, lymph nodes, kidney, heart and tonsils[8–11]. Pituitary carcinomas have a greater tendency toward systemic metastasis than craniospinal metastasis with poorer outcome for systemic disease compared with craniospinal involvement[4,12]. It is generally agreed that distant metastasis should be documented as a prerequisite to establish the diagnosis of a pituitary carcinoma. Current neuroimaging modalities, CT and particularly MR scanning, exert high sensitivity in detecting pituitary pathology; in addition, these techniques can be used to demonstrate disease progression elsewhere and thus the presence of metastasis even when the pituitary has remained stable[5,13]. FDG-PET provides information that is not obtainable with the aforementioned imaging modalities, and is very effective in the diagnosis and management of patients with various types of cancer. When we utilize an integrated PET/CT system, we are able to get even more accurate results providing both anatomical and functional imaging at the same position. It seems FDG-PET/CT could be useful in detecting distant metastasis of pituitary carcinoma; other imaging modalities fail to detect all of them.

Footnotes

This paper is available online at http://www.cancerimaging.org. In the event of a change in the URL address, please use the DOI provided to locate the paper.

References

- 1.Pernicone PJ, Scheithauer BW, Sebo TJ, et al. Pituitary carcinoma, a clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. Cancer. 1997;79:804–12. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970215)79:4<804::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-3. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19970215)79:4<804::AID-CNCR18>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cairns H, Russel DS. Intracranial and spinal metastasis in gliomas of the brain. Brain. 1931;54:377–420. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Long MA, Colquhoun IR. Case report: multiple intracranial metastases from a prolactin-secreting pituitary tumor. Clin Radiol. 1994;49:356–8. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)81807-0. doi:10.1016/S0009-9260(05)81807-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ragel BT, Couldwell WT. Pituitary carcinoma: a review of literature. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;16 doi: 10.3171/foc.2004.16.4.8. doi:10.3171/foc.2004.16.4.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaltas GA, Nomikos P, Kontogeorgos G, Buchfelder M. Clinical review: diagnosis and management of pituitary carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3089–99. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2231. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaltas GA, Grossman AB. Malignant pituitary tumors. Pituitary. 1998;1:69–81. doi: 10.1023/a:1009975009924. doi:10.1023/A:1009975009924. PMid:11081185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi G, Kim YM, Choi SH, et al. Pituitary carcinoma with mandibular metastasis: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22((Suppl):):S145–8. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2007.22.S.S145. doi:10.3346/jkms.2007.22.S.S145. PMid:17923742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed M, Kanaan I, Alarifi A, et al. ACTH-producing pituitary cancer: experience at the King Faisal specialist hospital and research center. Pituitary. 2000;3:105–12. doi: 10.1023/a:1009957824871. doi:10.1023/A:1009957824871. PMid:11141693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lubke D, Wolfgang S. Carcinomas of the pituitary; definition and review of the literature. Gen Diagn Pathol. 1995;141:81–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mount Castle RB, Mayfield RK, Morders DB, Sagel J, Biggs PL, Rawe SE. Case report: pituitary adrenocarcinoma in an acromegalic patient. Response to bromocriptine and pituitary testing. A review of the literature on 36 cases of pituitary carcinoma. Am J Med Sci. 1989;298:109–18. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198908000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamjoom A, Moss T, Coakham H, Jamjoom AZ, Anthony P. Cervical lymph nodes metastases from a pituitary carcinoma. Br J Neurosurg. 1994;8:87–92. doi: 10.3109/02688699409002399. doi:10.3109/02688699409002399. PMid:8011201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figueirdo EG, Paiva WS, Teixeira MJ. Extremely late development of pituitary carcinoma after surgery and radiotherapy. J Neurooncol. 2009;92:219–22. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9748-5. doi:10.1007/s11060-008-9748-5. PMid:19034384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaiser FE, Orth DN, Mukai K, Oppenheimer JH. A pituitary parasellar tumor with extracranial metastases and high, partially suppressible levels of adrenocorticotropin and related peptides. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1983;57:649–53. doi: 10.1210/jcem-57-3-649. doi:10.1210/jcem-57-3-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]