Abstract

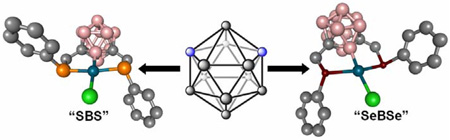

We report the synthesis of several unique, boron-rich pincer complexes derived from m-carborane. The SeBSe and SBS pincer ligands can be synthesized via two independent synthetic routes, and are metallated with Pd(II). These structures represent unique coordinating motifs, each with a Pd-B(2) bond chelated by two thio- or selenoether ligands. This class of structures serves as the first example of boron-metal pincer complexes, and possesses several interesting electronic properties imposed by the m-carborane cage.

Pincer complexes,1 formed from tridentate ligands (the “pincer”) and metals or metalloids, are an exciting class of structures with utility in catalysis,2 molecular electronics,3 and medicine.4 The pincer ligand provides tailorability with respect to 1) anchoring site on the base, the central moiety from which the arms extend,5a 2) metal-binding heteroatoms, which control the electronic nature of the complexed atom,5b and 3) the auxiliary sites on the arms,5c which can be modified to control the chirality of the resulting structure and the steric environment around the complexed atom. To date, the base has been made primarily from hydrocarbons, including aromatic groups such as benzene and heteroatom analogs,6a aliphatic groups,6b–c and, more recently, carbene-type moieties.6d

Icosahedral carboranes represent one class of structures7 that have not been explored as base units in pincer complexes. This is surprising considering these structures are highly tailorable,8a exhibit extraordinary stability,8b and provide a wide range of accessible chemical derivatization pathways.8c Indeed, Hawthorne et al. have pioneered synthetic methods for preparing metallacarboranes,9a–b the metallocene analogs of carboranes. These studies have led to many important discoveries pertaining to the fundamental chemistry of boron-containing cage structures and to their applications in nuclear waste remediation9c and as potential pharmaceuticals.9d

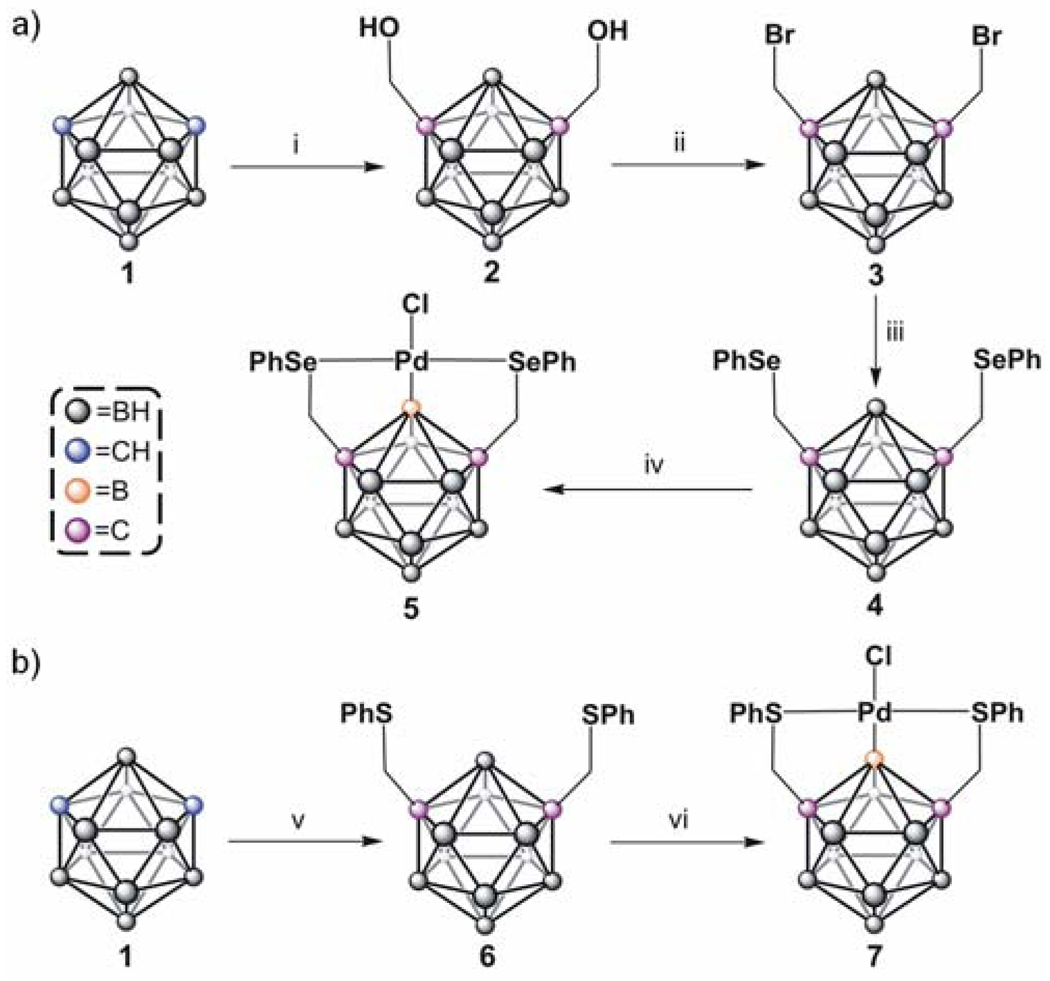

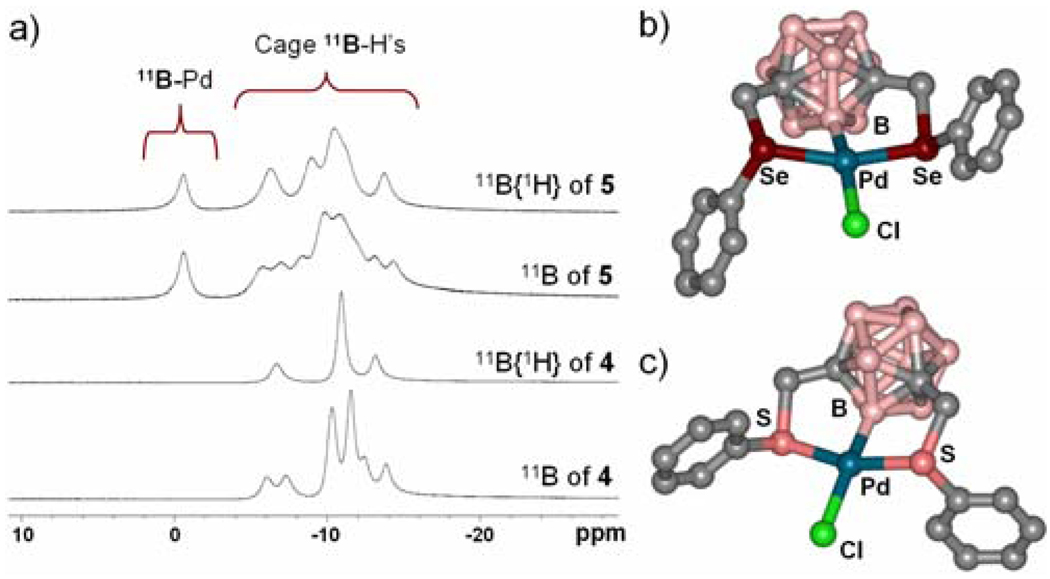

Herein we report the first carborane-based pincer ligand family and the complexes of these ligands metallated with Pd. The structure formed represents a new class of compounds with a previously unobserved Pd-B σ-coordination bond pincer motif.10 Additionally, through density functional theory (DFT) calculations we show that the electronic structure of this novel complex, derived in part from this new ligand, is substantially different from its hydrocarbon analogues. The carborane-based pincer complex 5 was synthesized in four steps starting with the commercially available m-carborane 1 (Scheme 1a) to form the desired pincer ligand 4. Pincer complex 5 is made in 76% yield by reacting ligand 4 with Pd(CH3CN)4[BF4]2 in acetonitrile followed by 2 eq. of (nBu)4NCl. Importantly, complex 5 is stable indefinitely in air and can be chromatographed on silica. All spectroscopic data are consistent with the proposed structure for 5. For example, the mass spectrum of 5 exhibits a [M+Cl]− ion at 659 m/z in negative ionization mode and [2M-Cl]+ at 1210 m/z in positive mode as the highest intensity peaks, respectively. Elemental analysis (C, H, Cl) confirms the elemental ratio of the pincer complex. The 11B NMR spectra of ligand 4 and its Pd(II) complex 5 are consistent with the proposed complexation of Pd (Figure 1a). Complexation results in a 10 ppm down field shift for the 11B resonance associated with the B-Pd bond. Metalation of ligand 4 breaks the C2v symmetry of its parent m-carborane cage and results in a larger number of 11B resonances as compared with the spectrum for 4. The 11B{1H} spectrum of 5 consists of a region of four overlapping singlet resonances (from δ -3 to -18) and an isolated resonance at δ - 0.7. Integration of the area under these peaks shows a 9:1 ratio, respectively. The 1H coupled 11B NMR spectrum of complex 5 exhibits a broad multiplet in the δ -3 to -18 region of the spectrum but the resonance at δ - 0.7 remains a singlet, consistent with its assignment as the B(2) atom bound to Pd(II).10a This B atom is the only one not bound to a hydrogen atom and therefore remains a singlet in the proton-coupled 11B NMR spectrum.

Scheme 1.

Syntheses of 5 and 7: (i) n-BuLi, ether, paraform, reflux, 85% (ii) Br2, PPh3, benzene, reflux, 78% (iii) PhSeSePh, NaBH4, ethanol, reflux, 72% (iv) Pd(CH3CN)4[BF4]2, CH3CN, reflux, then (nBu)4NCl (2 eq.), 76%. (v) MeLi, ether, then ClCH2SPh, 66% (vi) same as (iv), 71%.

Figure 1.

(a) 11B NMR based structural evidence for pincer ligand 4 and its palladated complex 5. (b)–(c) Crystallographically derived molecular structures of 5 and 7 respectively (hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity; the carbons are grey and the borons light coral).

Temperature-dependent 77Se NMR spectroscopy is also consistent with the proposed structure for 5. At room temperature, 77Se{1H} NMR (see SI-12) reveals three broad resonances13 at δ 505, 535 and 543 ppm, respectively, which are assigned to the interconverting conformational forms of complex 5 in solution. Cooling the sample to −20 °C leads to resolution of the resonances and four distinct peaks. Two of these (δ 545.2 and 506.1) are assigned to the syn isomers, both of which have magnetically equivalent Se atoms. The remaining two, at δ 504.1 and 533.6, are assigned to the anti isomer, which contains magnetically inequivalent Se atoms due to the different faces of the carborane cage. Importantly, if one compares the 77Se NMR resonance for ligand 4 (δ 354.1) with the resonances assigned to the different conformations of 5, one finds a ~ δ 180 downfield shift, consistent with Pd(II) complexation. Fluxional behavior was also confirmed via 13C NMR (See SI-14). 1H NMR spectroscopy also shows a significant broadening of the CH2-arm moiety resonances, attributed to the syn and anti isomers of 5. A temperature dependent 1H NMR study enabled us to estimate the activation energy for this process to be ~64 kJ/mol (see SI-13), based upon coalescence temperature and literature methods.11

Finally, the solid-state molecular structure of 5 was determined by single crystal X-Ray diffraction methods. The Pd(II) center exhibits a distorted square planar coordination geometry, with two selenoether ligands coordinated to in a trans fashion (Figure 1b) and a chloride atom ligated to Pd(II) in a trans fashion to B(2). The Pd-Cl bond length (2.44 Å) in 5 is slightly longer than similar motifs in aryl-based pincers (See SI-21, ref. S5), indicating a stronger trans influence of the 2-boryl moiety on the m-carborane cage than its phenyl analogue. The Pd-B distance is one of the shortest (1.98 Å) reported to date (see SI-21, ref. S4), based on a search performed in the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center. To our knowledge, this structure represents the first crystallographically characterized Pd-B σ bond in carborane systems, and the first metal-boron(2) bond in m-carborane chemistry.

“XBX” pincer complexes, where X is a general heteroatom, have not yet been made and therefore, a general route to such structures is of a fundamental interest. As a demonstration of generality in accessing ligands with different heteroatom arm moieties we also synthesized and characterized the thioether, “SBS”, analogue of 4, ligand 6 and its corresponding Pd(II) complex 7. Pincer ligand 6 was synthesized in one step, via the dilithiation of m-carborane 1 and subsequent alkylation with commercially available α-chlorothioanisole (Scheme 1b). This ligand was palladated following the procedure used to prepare complex 5. Single crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure 1c), mass spectrometry (showing a similar fragmentation pattern), and 11B NMR spectroscopy (see SI-17) confirm that 7 is the thioether analogue of 5. Interestingly, 1H and 13C NMR spectra of 7 (see SI-19–20) suggest that only the anti-conformation of the complex exists at room temperature and below, unlike its “SeBSe” counterpart 5. This is likely due to the larger trans effect imposed by a selenoether moiety, which weakens the Se-Pd bond and lowers the interconversion barrier.12

Preliminary DFT calculations (see SI-5–8) provide interesting insights with respect to this unique structural motif. Based on calculated Mulliken and Löwdin charge densities, there is a net negative charge localized on the Pd atom and a relative positive charge concentrated on B(2), compared to other borons in the cage. These calculations also suggest a single bond between the Pd and B. Furthermore, the Pd-B bonds in complexes 5 and 7 exhibit strong σ-electron donation with little π-back bonding; whereas some Pd-C analogues1 have significant multiple bond character with both σ-electron donation and π-back bonding. Taking into consideration that the electronegativity of palladium is higher than boron,13 the possibility of Pd bearing a formal oxidation state of zero in 5 and 7 cannot be dismissed at this point.

Work towards probing the stoichiometric and catalytic chemistry14 of these complexes is currently underway. In particular, we are interested in exploring the nature of the M-B bond in carboranes, which was recently suggested to be more thermodynamically stable than the M-C analog.15 In addition, this is a novel type of hemilabile ligand which can be used for preparing a wide variety of supramolecular architectures, a primary focus of our current research.16

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Omar Farha for helpful suggestions. C.A.M. acknowledges NSF, ARO and NIH Director’s Pioneer Award for generous financial support. M.G.R. acknowledges the DoE Computational Science Graduate Fellowship Program for support (grant No. DE-FG02-97ER25308). M.A.R. and T. S. acknowledge NSF-CHEM for partial support. We thank IMSERC for analytical instrumentation help.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental and characterization for 4–7. X-ray crystallographic files for 5 and 7 in CIF format. Details on DFT studies of 5. These materials are available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Morales-Morales D, Jensen CM. The Chemistry of Pincer Compounds. Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singleton JT. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:1837–1857. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albrecht M, Van Koten G. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:3750–3781. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011015)40:20<3750::AID-ANIE3750>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melaiye A, Simons RS, Milsted A, Pingitore F, Wesdemiotis C, Tessier CA, Youngs WJ. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:973–977. doi: 10.1021/jm030262m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Szabo KJ. Syn. Lett. 2006;6:0811–0824. [Google Scholar]; b Gunanathan C, Ben-David Y, Milstein D. Science. 2007;317:790–792. doi: 10.1126/science.1145295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Benito-Garagorri D, Kirchner K. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:201–213. doi: 10.1021/ar700129q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Gossage RA, Van De Kuil LA, Van Koten G. Acc. Chem. Res. 1998;31:423–431. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhao J, Goldman AS, Hartwig JF. Science. 2005;307:1080–1082. doi: 10.1126/science.1109389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ozerov OV, Watson LA, Pink M, Caulton KG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:6003–6016. doi: 10.1021/ja062327r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kubo K, Jones DN, Ferguson MJ, McDonald R, Cavell RG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:5314–5315. doi: 10.1021/ja0502831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grimes RN. Carboranes. New York: Academic Press; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Plesek J. Chem. Rev. 1992;92:269–278. [Google Scholar]; (b) Farha OK, Spokoyny AM, Mulfort KL, Hawthorne MF, Mirkin CA, Hupp JT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:12680–12681. doi: 10.1021/ja076167a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Teixidor F, Barberà G, Vaca A, Kivekäs R, Sillanpää, Oliva J, Viñas C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:10158–10159. doi: 10.1021/ja052981r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawthorne MF. Acc. Chem. Res. 1968;9:281–288. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hawthorne MF, Zink J, Skelton JM, Bayer MJ, Liu C, Livshits E, Baer R, Neuhauser D. Science. 2004;303:1849–1851. doi: 10.1126/science.1093846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Law JD, Brewer KN, Herbst RS, Todd TA, Wood DJ. Waste Management. 1999;19:27–37. [Google Scholar]; (d) Cígler P, Kozísek M, Rezácová P, Brynda J, Otwinowski Z, Pokorná J, Plesek J, Grüner B, Dolecková-Maresová L, Mása M, Sedlácek J, Bodem J, Kräusslich H-J, Král V, Konvalinka J. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:15394–15399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507577102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoel EL, Hawthorne MF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:6388–6395. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kalinin VN, Usatov AV, Zakharkin LI. Proc. Indian Natn. Sci. Acad. 1989;55:293–317. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Manen H-J, Nakashima K, Shinkai S, Kooijman H, Spek AL, Frank van Veggel FCJM, Reinhoudt DN. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2000:2533–2540. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cross RJ, Green TH, Keat R. Chem. Soc. Dalton. Trans. 1976:1150–1152. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cotton FA, et al. Advanced Inorganic Chemistry. 6th Edition. Wiley; [Google Scholar]

- 14.French CM, Shimon LJW, Milstein D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:1709–1711. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schwartsburd L, Cohen R, Konstantinovski L, Milstein D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:3603–3606. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu D, Dang L, Chan H-S, Lin Z, Xie Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:16103–16110. doi: 10.1021/ja8067098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon HJ, Mirkin CA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:11590–11591. doi: 10.1021/ja804076q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Oliveri CG, Ulmann PA, Wiester MJ, Mirkin CA. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1618–1629. doi: 10.1021/ar800025w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gianneschi NC, Nguyen ST, Mirkin CA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:1644–1645. doi: 10.1021/ja0437306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Gianneschi NC, Bertin PA, Nguyen ST, Mirkin CA, Zakharov LV, Rheingold AL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:10508–10509. doi: 10.1021/ja035621h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.