Abstract

It has been well established that articular cartilage is compositionally and mechanically inhomogeneous through its depth. To what extent this structural inhomogeneity is a prerequisite for appropriate cartilage function and integrity, is not well understood. The first hypothesis to be tested in this study was that the depth-dependent inhomogeneity of the cartilage acts to maximize the interstitial fluid load support at the articular surface, to provide efficient frictional and wear properties. The second hypothesis was that the inhomogeneity produces a more homogeneous state of elastic stress in the matrix than would be achieved with uniform properties. We have, for the first time, simultaneously determined depth-dependent tensile and compressive properties of human patellofemoral cartilage from unconfined compression stress-relaxation tests. The experimental measurements were then implemented with the finite element method to compute the response of an inhomogeneous and homogeneous cartilage layer to loading. The results show that the tensile modulus increases significantly from 4.1±1.9MPa in the deep zone to 8.3±3.7MPa at the superficial zone, while the compressive modulus decreases from 0.73±0.26MPa to 0.28±0.16MPa. The finite element models demonstrate that structural inhomogeneity acts to increase the interstitial fluid load support at the articular surface. However, the state of stress, strain, or strain energy density in the solid matrix remained inhomogeneous through the depth of the articular layer, whether or not inhomogeneous material properties were employed. We suggest that increased fluid load support at the articular surface enhances the frictional and wear properties of articular cartilage, but that the tissue is not functionally adapted to produce homogeneous stress, strain, or strain energy density distributions. Interstitial fluid pressurization, but not a homogeneous elastic stress distribution, appears thus to be a prerequisite for the functional and morphological integrity of the cartilage.

Introduction

It is well known that cartilage exhibits inhomogeneity through its depth, histologically, biochemically [1,2], and mechanically [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. However, there is currently no clear understanding how the zonal inhomogeneity of the cartilage develops during chondrogenesis, and whether it is required for appropriate cartilage function and morphological integrity of the tissue. It has been hypothesized that excessive stresses in cartilage might represent one of the initiating causes of osteoarthritic degeneration [10]. An accurate determination of the state of stress within the tissue has therefore been an important objective in the field of cartilage biomechanics.

In other biological soft tissues, such as the arterial wall [11], it has been suggested that the tissue structure produces a uniform state of stress through its thickness. Though adult articular cartilage has a limited ability to remodel itself in response to its loading environment, it is legitimate to inquire whether the structure of adult cartilage has been optimized during early development to produce a homogeneous state of stress, strain, or strain-energy density in the solid collagen-proteoglycan matrix. It has also been proposed that interstitial fluid pressurization in articular cartilage plays a primary role in producing low friction and wear [12,13,14,15,16] as well as in shielding the collagen-proteoglycan solid matrix from a significant portion of the loads applied across joints [17,18,19,20]. Since friction and wear phenomena occur primarily at the articular surface and in the superficial zone, it is possible that the structure of articular cartilage is also optimized to enhance the tissue’s tribological response at the articular surface.

Based on these arguments, the current study was designed to test the following hypotheses: 1) The inhomogeneity of articular cartilage acts to maximize the interstitial fluid load support at the articular surface; 2) The depth-dependent inhomogeneous distribution of cartilage properties acts to produce a more homogeneous state of elastic stress in its extracellular matrix than would otherwise be achieved with uniform properties through the depth. To this end we have simultaneously determined the depth-dependent tensile and compressive properties of human patellofemoral cartilage, computed the response of cartilage to loading under a contact configuration using finite element models which employ these experimentally determined material properties; and compared the response of the tissue to a hypothetical homogeneous distribution of material properties.

In this study, cartilage is modeled using a porous media theory [21] to properly distinguish between interstitial fluid pressurization and the stress, strain, and strain-energy density resulting from the elastic deformation of the collagen-proteoglycan matrix. Care is also taken to account for the disparity in tensile and compressive properties of the tissue, which has been shown to play a significant role in its functional response [9,22,23,24,25,26,27].

Materials and Methods

Experimental Measurements of Depth-Dependent Material Properties

Experimental measurements of material properties are dependent upon the choice of a constitutive formulation in which these properties regulate the response of the material. The current study employs the biphasic-conewise linear elastic (CLE) formulation proposed recently [25], which accounts for the porous-permeable nature of articular cartilage as well as its tension-compression nonlinearity. The material properties for this model consist of the aggregate modulus in compression, H−A , and in tension, H−A ; the “off-diagonal” modulus λ2 (which relates the equilibrium normal stress exerted on the side wall of a confining chamber to the axial compressive strain); the shear modulus, µ; and the hydraulic permeability k , which regulates the flow of interstitial fluid within the porous-permeable solid matrix. This biphasic-CLE model has been validated under the testing configurations of confined and unconfined compression, and torsional shear, where it has been shown to properly curvefit the load response of cartilage under those testing conditions, as well as predict the interstitial fluid response in unconfined compression [25]. In the current study, confined and unconfined compression stress-relaxation tests were performed on four serial slices of full-thickness plugs of human patellofemoral joint articular cartilage, to produce the material constants H−A, H−A, λ2 , and k as a function of depth.

Visually normal cylindrical cartilage samples (diam. 4.78mm) were harvested from the center of the patellar cartilage layer and the center of the trochlear groove of the distal femoral cartilage, from six fresh frozen human cadaver knees (4 males, 2 female, ages 45.5±12.0 years; average thickness 2.41±0.32 mm for the femur and 2.56±0.22 mm for the patella). About 0.2 mm of tissue was removed from the deep zone to produce a surface parallel to the articular surface, using a sledge microtome (Model 1400; Leitz, Rockleigh, NJ). Each sample was then serially sliced into four layers starting from the deep zone. The first three slices were approximately of the same thickness (0.43±0.043 mm for the femur and 0.55±0.086 mm for the patella; spanning deep and middle zones) while the more superficial slice consisted of the remainder (1.13±0.26 mm for the femur and 0.90±0.26 mm for the patella; spanning middle and surface zones). Specimens were frozen in normal phosphate buffered saline at −25°C until the day of testing; no protease inhibitors were used in this study. The testing apparatus and protocols for confined and unconfined compression stress-relaxation, and the procedures for extracting material properties from these tests, were identical to those of our recent study on bovine cartilage [25] and are briefly summarized here.

For unconfined compression experiments, the tissue was compressed between a stainless steel loading platen and the impermeable bottom surface of the aluminum test chamber. A tare load of 0.89 N (50 kPa) was first applied; following equilibrium, a stress relaxation experiment was initiated where the top platen was ramped at a constant strain rate, reaching 10% tissue strain in 500 seconds, at which time the displacement was maintained constant. The unconfined compression reaction force was recorded as a function of time. At the completion of the stress relaxation test the tissue was unloaded and allowed to re-equilibrate for 1 hour. For confined compression tests, the specimen was loaded into an aluminum confining chamber, 4.78 mm in diameter. Loading was applied on the specimen via a 4.76 mm diameter porous stainless steel indenter (pore size ~50 µm). The same loading protocol was used as for unconfined compression, starting with the tare load and followed by the axial tissue displacement. The confined compression reaction force at the articular surface was recorded as a function of time. For each specimen, both confined and unconfined compression relaxation tests were performed on the same day; the order of testing from specimen to specimen was randomized. The stress-relaxation tests were terminated when the rate of change in the load was less than 0.02 N over 500 s.

For both tests, a least-squares curvefitting algorithm was used to estimate the material parameters. This was achieved by matching the experimentally measured transient reaction force with the corresponding theoretical response, using a numerical finite difference scheme for solving the governing differential equations for these configurations, as described previously [25]. Curvefitting was performed using the BFGS quasi-Newton optimization method for minimizing a function with simple bounds using a finite-difference gradient (IMSL Fortran Numerical Libraries, Visual Numerics, Houston, TX), with the objective function given by the root-mean-square of the residual error between the experimental and theoretical load responses. The parameter H−A was determined from the near-equilibrium response in confined compression. The permeability in the axial direction kz was then obtained by curvefitting the entire transient confined compression load response, including both ramp and relaxation. Using this value of H−A, the parameters H−A, λ2 and kr (the permeability in the radial direction) were obtained by curvefitting the total load response from unconfined compression. The shear modulus µ was not measured directly in the current study. An estimate for µ was derived from the approximate relation µ ≈ (H−A – λ2)/2. For each of the patellar and trochlear groove cartilage, the experimentally determined material properties from six human knees were averaged for each of the four serial slices through the depth. A quadratic polynomial was least-squares fitted to each of the depth-dependent average properties (H−A, H+A, λ2, µ, kz, kr), to produce a continuous distribution of that property through the articular layer thickness. For each of the patella and femur, statistical differences through the depth, for each of the four slices, were investigated with a one-way analysis of variance with repeated measures on the factor of depth, with α=0.05, and Bonferroni-corrected post-hoc test.

Finite Element Analysis of Contact Configuration

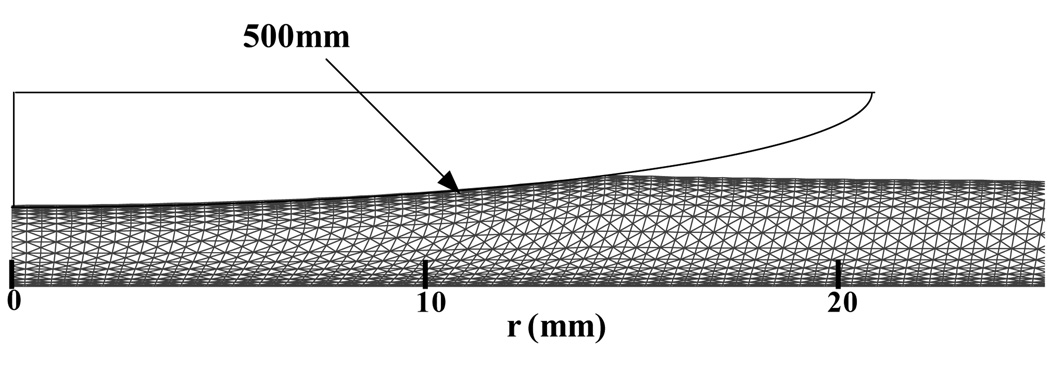

While a most realistic finite element analysis should accommodate three-dimensional contact of the patella with the trochlear groove [28,29,30,31,32], the current analysis resorted to a number of simplifications regarding the contact geometry. A custom written finite element code was employed to perform an axisymmetric contact analysis of a spherical impermeable rigid indenter of radius 500mm with a uniformly thick biphasic-CLE cartilage layer representing either the patellar cartilage or the trochlear groove cartilage (Figure 1). This analysis employed a small-strain displacement-pressure (u-p) formulation [33,34] and accounted for the nonlinear (piecewise linear) stress strain constitutive relations of the CLE model using standard finite element modeling procedures [35]. Eight node isoparametric elements were used in a mesh of 2033 nodes and 640 elements (40 elements along the radial direction and 16 increments along the depth); mesh biases were created to produce more elements near the articular surface and the subchondral bone to improve accuracy in the enforcement of interface conditions. Convergence of the solution was verified by mesh refinement. At the contact interface with the impermeable sphere, the shear traction was set to zero (frictionless contact), the normal component of the fluid flux was set to zero (impermeable indenter), and the axial surface displacement was prescribed to follow the indenter contour, given the spherical radius of the indenter and its normal approach (depth of penetration). The contact region was determined iteratively at a given time step by simultaneously requiring that the normal component of the contact traction be compressive at every node in the contact region and that the nodal axial displacement match the spherical profile of the indenter. Outside of the contact region, the fluid pressure and normal and shear traction components were set to zero at the articular surface. At the deep zone, the cartilage layer was bonded to a rigid impermeable substrate representing subchondral bone, while the lateral free surface of the cartilage layer was unconstrained and free draining.

Figure 1.

Contact geometry and finite element mesh in the deformed configuration. The mesh deformation has been scaled up for emphasis in this figure.

For the inhomogeneous models, material properties were assigned at the center of each finite element according to its axial location through the depth of the articular layer, using the quadratic polynomial approximation of the depth-dependent experimental data. For the homogeneous models, one single mean value was used over the entire finite element mesh for each of the material properties, obtained by integrating the quadratic polynomial approximation of that property through the depth of the tissue and dividing the result by the articular layer thickness. In all, four finite element analyses were performed, consisting of an inhomogeneous and a homogeneous analysis for each of the patellar and trochlear cartilages.

Loading was applied by adjusting the normal approach such as to achieve a contact load of ~150N between the spherical indenter and the articular layer. A time step of 1s was employed in the finite element analyses. While the biphasic-CLE model is able to produce a time-dependent response until equilibrium is achieved, the early time response is the most relevant from a physiological perspective (e.g., [17,36]). Hence, the solution results presented below correspond to the response at the end of the first time step following load application.

Results

The coefficients of determination for the curve-fits and the duration of the stress-relaxation tests are provided in Table 1. In the femur, the cartilage properties varied significantly with depth, specifically H− A, H−A, λ2, and kr (Table 1). In the patella, significant differences were found for H−A, H−A, λ2, and kz. In both the femur and patella, H−A and λ2 decreased from the deep zone to the joint surface, whereas H−A displayed a significant increase towards the surface (Table 1). In the femur, the permeability kr in the radial direction (tangential to the articular surface) decreased from the deep zone to the articular surface, whereas in the patella no difference was observed among the layers, though the trend in kz was to also decrease from deep to superficial. The radial permeability was found to be significantly greater than the axial permeability in all layers of the femur (p<0.05) and in layer 3 of the patella (p<0.002) [25]. Since it is straightforward to obtain quadratic polynomial fits of the mean values of the material properties in Table 1 as a function of the depth coordinate z, the polynomial coefficients are not provided here. These polynomials were used to generate depth-dependent properties for the inhomogeneous finite element models of the articular layers, and average properties for the homogeneous models.

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviation of experimentally determined material properties (H−A, kz, H+A, λ2, kr) as a function of depth (layer 1=bone side, layer 4=articular surface side) and p-values from one-way analysis of variance for the factor of depth. Statistically significant differences between layers are indicated with matching superscripts (p<0.05). Layer thickness (h), depth coordinate (z), coefficients of determination for curve-fits in unconfined compression (UC) and confined compression (CC), and time to reach equilibrium (teq), are provided in subsequent columns.

| Femur | H−A | kz × 1015 | H+A | λ2 | kr × 1015 | h | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MPa) | (m4/N.s) | (MPa) | (MPa) | (m4/N.s) | (mm) | (mm) | |

| Layer 1 | 0.73±0.17ab | 0.58±0.36 | 4.07±1.79a | 0.29±0.10a | 1.86±0.70a | 0.44±0.07 | 0.22±0.03 |

| Layer 2 | 0.59±0.20c | 0.44±0.44 | 4.61±1.67b | 0.32±0.07b | 1.31±0.49 | 0.41±0.03 | 0.64±0.07 |

| Layer 3 | 0.46±0.13a | 0.59±0.39 | 5.07±1.84c | 0.26±0.07 | 1.18±0.41 | 0.42±0.03 | 1.06±0.08 |

| Layer 4 | 0.32±0.14bc | 0.39±0.31 | 10.1±4.46abc | 0.17±0.10ab | 1.00±0.39a | 1.14±0.26 | 1.84±0.11 |

| p-value | 0.0002 | 0.4308 | 0.0015 | 0.006 | 0.0327 | ||

| Femur |

r2 (Unconfined compression) |

r2 (Confined Compression) |

teq (UC) (s) |

teq (CC) (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layer 1 | 0.976±0.008 | 0.907±0.087 | 3,758±600 | 5,223±2167 |

| Layer 2 | 0.979±0.023 | 0.900±0.100 | 3,750±592 | 4,500±1265 |

| Layer 3 | 0.966±0.043 | 0.861±0.128 | 4,225±992 | 4,333±606 |

| Layer 4 | 0.987±0.003 | 0.939±0.017 | 4,342±1372 | 3,792±510 |

| Patella | H−A | kz × 1015 | H+A | λ2 | kr × 1015 | h | z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (MPa) | (m4/N.s) | (MPa) | (MPa) | (m4/N.s) | (mm) | (mm) | |

| Layer 1 | 0.73±0.34ab | 0.79±0.46 | 4.16±1.94a | 0.31±0.25a | 1.37±0.73 | 0.56±0.09 | 0.28±0.04 |

| Layer 2 | 0.58±0.26c | 0.71±0.63 | 4.46±1.76 | 0.23±0.10 | 1.08±0.47 | 0.54±0.09 | 0.83±0.12 |

| Layer 3 | 0.40±0.21a | 0.32±0.13 | 4.66±1.36 | 0.18±0.06 | 1.19±0.28 | 0.55±0.09 | 1.38±0.20 |

| Layer 4 | 0.25±0.18bc | 0.21±0.07 | 6.55±3.03a | 0.07±0.16a | 1.58±1.42 | 0.91±0.26 | 2.1±0.26 |

| p-value | <0.0001 | 0.0321 | 0.0251 | 0.0096 | 0.7218 | ||

| Patella | r2 (UC) | r2 (CC) |

teq (UC) (s) |

teq (CC) (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Layer 1 | 0.970±0.02 | 0.929±0.048 | 4,633±1794 | 4,408±1949 |

| Layer 2 | 0.984±0.004 | 0.911±0.101 | 3,850±1198 | 4,133±882 |

| Layer 3 | 0.974±0.012 | 0.918±0.079 | 4,500±632 | 4,042±1249 |

| Layer 4 | 0.986±0.004 | 0.940±0.029 | 4,375±945 | 4,225±1765 |

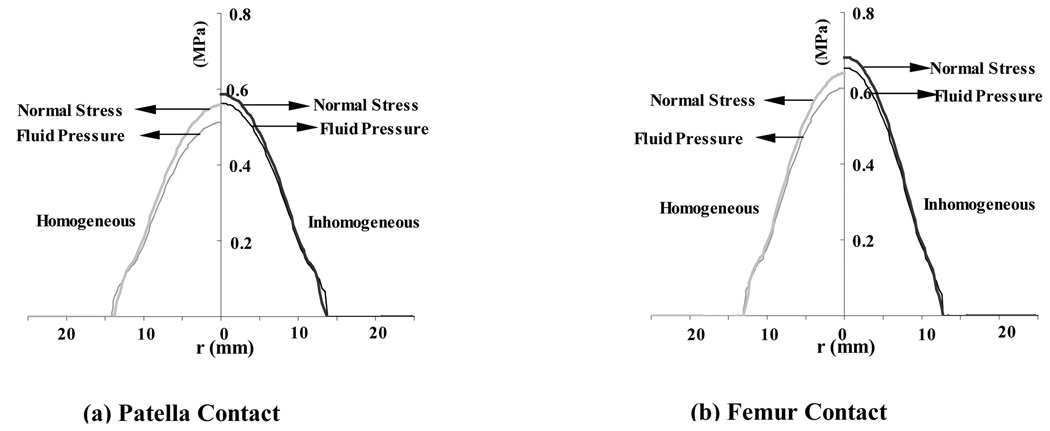

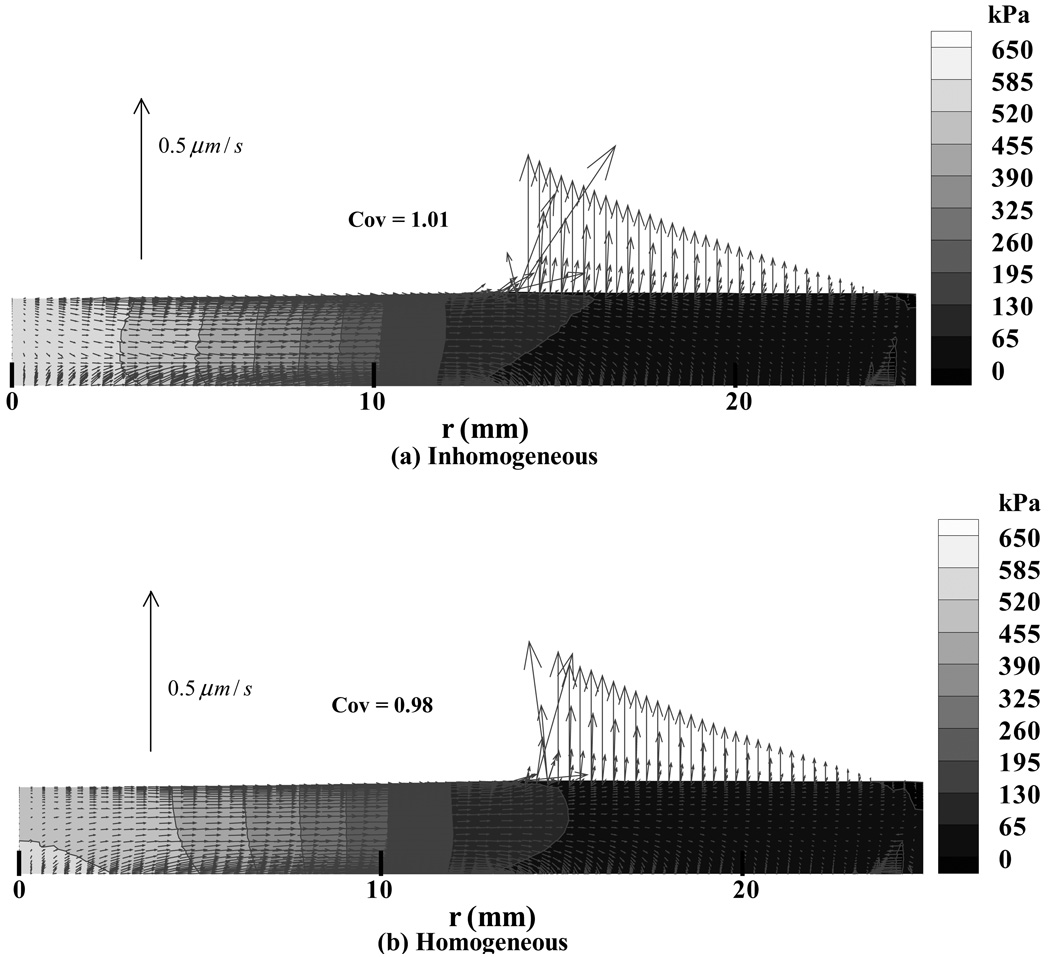

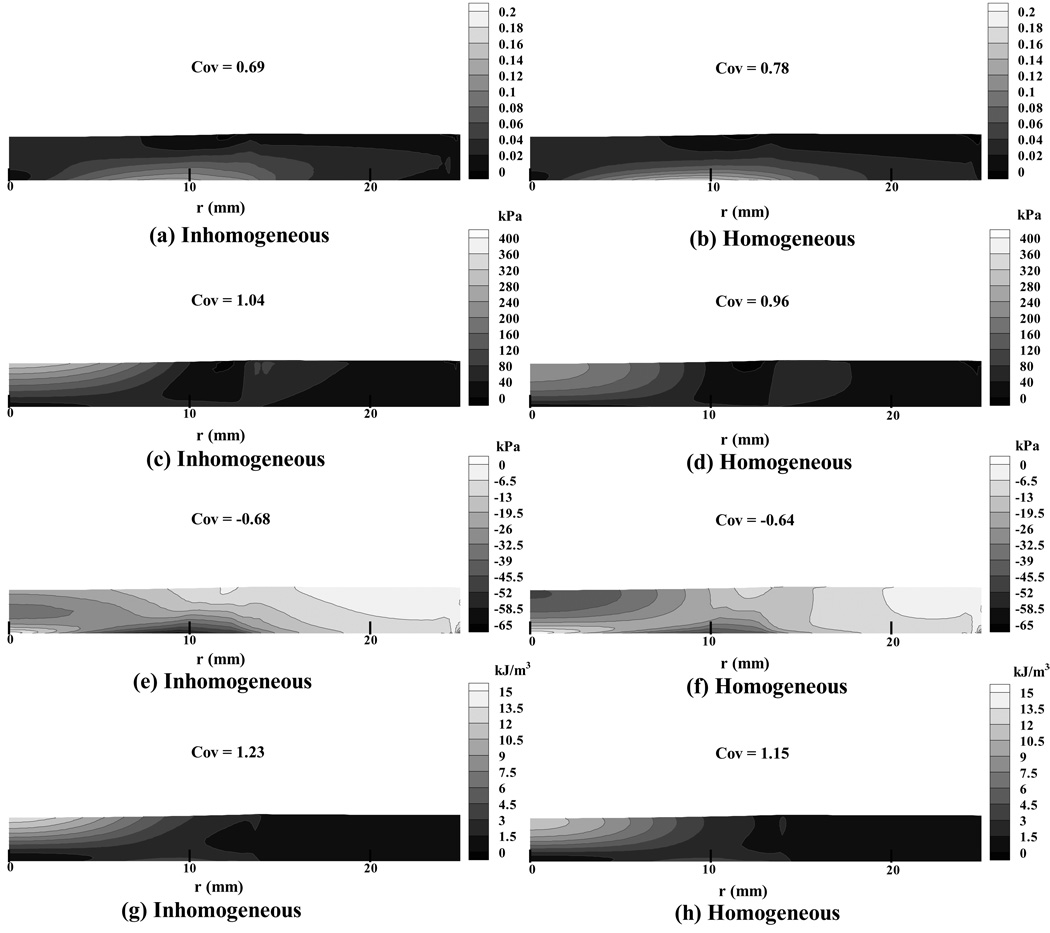

From the finite element analyses a number of results were evaluated though only a subset, considered representative, is presented here. Throughout the presentation of pressure and stress results, it should be kept in perspective that in a biphasic material the total stress is given by σ=−pI+σe, where p is the interstitial fluid pressure, I the identity tensor, and σe the effective (or elastic) stress tensor which results from the strain in the solid matrix. Both p and the normal component of the total traction, n·σn (where n is the unit normal to the articular surface), are presented in Figure 2, showing how significant the contribution of the pressure is to the total normal traction. Also apparent in that figure is the radius a of the circular contact region (Table 2). The total contact force W can be evaluated by integrating the normal component of the total traction over the contact area, W =∫An·σndA; similarly, integrating the interstitial fluid pressure distribution produces that component Wp of the total load that is supported by interstitial fluid, Wp =∫ApdA (Figure 2). In the finite element models we observed that the interstitial fluid load support Wp/W at the articular surface was in the range of 93–98% in the four analyses. The fluid support was greater for the inhomogeneous models (Table 2), showing that the solid matrix was better protected by interstitial pressurization than in the homogeneous model. Since the relative fluid flux is proportional to the gradient in pressure (Darcy’s law), the direction of flow is perpendicular to the isobars (Figure 3). We observed that for the homogeneous distribution of material properties, the interstitial fluid pressure was higher at the cartilage-bone interface than at the articular surface, near the center of contact, whereas the models with inhomogeneous material properties showed more similar pressure magnitudes at the bone and articular surface (Figure 3, at r=0). However, the coefficients of variation for the interstitial pressure (Table 3) show that overall, the pressure is less uniform in the layers with inhomogeneous material properties, higher coefficients of variation indicating a less uniform distribution. The maximum principal normal strain (i.e., the highest eigenvalue of the strain tensor at a point) in the solid matrix (Figure 4 a,b) was found to be tensile throughout the articular layer, with its peak1 magnitude over the entire articular layer occurring at the cartilage-bone interface, away from the centerline of loading but under the footprint of the contact area (Table 4). The maximum shear strain and minimum normal strain showed a very similar distribution pattern, with the peak magnitudes occurring at the same location; the minimum normal strain was mostly compressive throughout the articular layer (data not shown). In the inhomogeneous models, a lower peak strain magnitude was observed than in the homogeneous models for the principal normal strains and maximum shear strain (Table 4), the effect being more pronounced in the femur.

Figure 2.

Total traction and interstitial fluid pressure at the contact interface between the cylindrical indenter and articular layer, at t = 1 s. Results are shown on the left for the homogeneous models and on the right for the inhomogeneous models. (a) Patellar contact. (b) Femoral contact.

Table 2.

Total contact force, W, load component supported by interstitial fluid pressure, Wp, interstitial fluid load support, Wp/W, and contact radius, a, at the contact interface for the four finite element analyses.

| Analysis | W (N) | Wp (N) | Wp/W | a (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femur homogeneous | 152 | 145 | 0.95 | 1.28 |

| Femur inhomogeneous | 151 | 146 | 0.97 | 1.25 |

| Patella homogeneous | 152 | 142 | 0.93 | 1.31 |

| Patella inhomogeneous | 152 | 149 | 0.98 | 1.34 |

Figure 3.

The interstitial fluid pressure field throughout the cartilage layer, at t = 1 s. Results are presented as a contour map together with vector arrows indicating the magnitude and direction of relative fluid flux, for the representative case of the patellar layer with (a) inhomogeneous and (b) homogeneous properties. The mesh deformation is shown to scale.

Table 3.

Coefficients of variation (standard deviation / mean) for the interstitial fluid pressure, principal normal effective stresses, principal normal strains, and strain energy density from the finite element analyses. Means and standard deviations are evaluated over the entire articular layer. A smaller COV is indicative of greater uniformity in the spatial distribution of that parameter.

| Femur | Patella | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhomogeneous | Homogeneous | Inhomogeneous | Homogeneous | |

| Interstitial fluid pressure | 1.08 | 1.04 | 1.01 | 0.98 |

| Minimum normal stress | −0.84 | −0.69 | −0.68 | −0.64 |

| Maximum normal stress | 1.24 | 1.05 | 1.04 | 0.96 |

| Maximum shear stress | 1.10 | 0.97 | 0.87 | 0.86 |

| Minimum normal strain | −0.62 | −0.62 | −0.54 | −0.57 |

| Maximum normal strain | 0.79 | 0.85 | 0.69 | 0.78 |

| Maximum shear strain | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.58 | 0.64 |

| Strain energy density | 1.33 | 1.23 | 1.23 | 1.15 |

Figure 4.

(a) & (b) Maximum principal normal strain distribution in the articular layer, at t = 1 s, for the inhomogeneous and homogeneous finite element models of the patella, respectively; (c) & (d) maximum principal normal effective stress; (e) & (f) minimum principal normal effective stress; (g) & (h) strain energy density distribution. The mesh deformation is shown to scale.

Table 4.

Magnitude and location of peak values of the principal normal and maximum shear strains.

| Analysis | Max. prin. normal strain |

Location z = 0 mm |

Min. prin. normal strain |

Location z = 0 mm |

Maximum shear strain |

Location z = 0 mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femur homogeneous |

0.204 | r =9.06 | −0.205 | r =9.06 | 0.204 | r =9.06 |

| Femur inhomogeneous |

0.130 | r =8.44 | −0.130 | r =8.44 | 0.130 | r =8.44 |

| Patella homogeneous |

0.174 | r =9.69 | −0.174 | r =9.69 | 0.174 | r =9.69 |

| Patella inhomogeneous |

0.134 | r =9.38 | −0.134 | r =9.38 | 0.134 | r =9.38 |

In contrast to the maximum normal strain, the maximum effective normal stress (Figure 4 c,d) exhibited its greatest magnitude at the articular surface, at the center of the contact area (Table 5). The maximum effective normal stress was tensile throughout the articular layer, and the maximum effective shear stress (data not shown) exhibited a similar distribution. The inhomogeneous models displayed substantially greater peak magnitudes and greater non-uniformity of maximum effective normal stress than the homogeneous models (Table 3 and Table 5). The minimum effective normal stress distribution (Figure 4e,f) exhibited some qualitative differences between the homogeneous and inhomogeneous models. For the homogeneous cases, elevated values of stress occurred both at the center of contact on the articular surface, and at the cartilage-bone interface away from the center of contact. For the inhomogeneous cases, elevated stresses occurred at the cartilage-bone interface away from the center of contact, and to a lesser extent, in the middle zone of the articular layer near the centerline of contact. In all cases, the minimum effective principal stress was compressive throughout most of the articular layer, exhibiting magnitudes much smaller than the maximum effective normal and maximum effective shear stresses (Table 5). The minimum effective normal stress distribution displayed a higher coefficient of variation, corresponding to lesser uniformity in the inhomogeneous models of the articular layers (Table 3). In all cases, we observed that the strain energy density (Figure 4 g,h) was greatest at the center of contact on the articular surface, decreasing toward the deep zone and toward the periphery of the contact region. The inhomogeneous models produced higher coefficients of variation for the strain energy density (Table 3), showing that this parameter was less uniform in the inhomogeneous models.

Table 5.

Magnitude and location of peak values of principal normal and maximum effective shear stress.

| Analysis | Max. prin. normal stress (kPa) |

Location r = 0 mm |

Min. prin. normal stress (kPa) |

Location z = 0 mm |

Maximum shear stress (kPa) |

Location r = 0 mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femur homogeneous |

292 | z =2.23 | −51 | r =9.06 | 165 | z =2.23 |

| Femur inhomogeneous | 480 | z =2.39 | −69 | r =8.13 | 254 | z =2.39 |

| Patella homogeneous |

221 | z =2.37 | −48 | r =9.69 | 133 | z =2.37 |

| Patella inhomogeneous |

314 | z =2.56 | −64 | r =9.06 | 169 | z =2.56 |

Discussion

The objective of this study was to investigate the functional benefits of the structural inhomogeneity of articular cartilage. The hypotheses were that the inhomogeneity of articular cartilage acts to maximize the interstitial fluid load support at the articular surface; and the depth-dependent inhomogeneous distribution of cartilage properties acts to produce a more homogeneous state of elastic stress in its extracellular matrix than would otherwise be achieved with uniform properties through the depth. To address these hypotheses, the first aim was to characterize the inhomogeneous properties of human patellofemoral cartilage by simultaneously determining the tensile and compressive elastic moduli of the solid matrix, along with the permeability coefficients, from a combination of confined and unconfined compression tests. The second aim was to compute the response of cartilage to contact loading using finite element models which employ these experimentally determined material properties; and compare the response of the tissue to a hypothetical homogeneous distribution of material properties.

The first hypothesis was supported by the results of this study, as presented in Table 2, showing that interstitial fluid load support at the articular surface is more elevated in the inhomogeneous models. Though the difference in interstitial fluid pressurization may seem small, the impact of these small changes on the frictional properties is very significant, as described below. The second hypothesis of this study was not supported by the results, as shown by the coefficients of variation for the stresses in Table 3, or the maps of principal normal stresses and maximum shear stress shown in Figure 4.

The contact analysis of this study represents a novel contribution by employing a porous media model which incorporates tension-compression nonlinearity of the solid matrix. In recent years, there has been a greater appreciation of the importance of tension-compression nonlinearity in the regulation of the functional response of articular cartilage [23,24,25,26,27], and this study represents the first time that these properties are determined within the same cartilage samples as a function of depth. Tensile properties can be derived from curvefitting the transient unconfined compression response because this testing configuration subjects the tissue to tensile strains in the radial and circumferential direction when compressed axially [22,23,24,25]; thus the transient response of the tissue is governed significantly by the tensile modulus. The experimental results confirm that the tensile modulus of cartilage is greatest at the articular surface and decreases toward the deep zone [4,5], while the compressive modulus follows an opposite trend [6,7,8,9].

It has long been recognized that interstitial fluid pressurization contributes considerably to the dynamic stiffness of articular cartilage. Using porous media theories such as the biphasic theory of Mow et al. [21], it has been possible to estimate the interstitial fluid load support for a variety of loading configurations. For example, in confined compression, the peak interstitial fluid load support at an impermeable interface is 100% for a short instant immediately upon loading, though this load support eventually decreases to zero after several thousand seconds, as confirmed experimentally [8,36,37,38]. In unconfined compression, linear isotropic biphasic theory predicts that the peak fluid load support cannot exceed 33% [39], even as the fluid load support under contact configurations could be as high as 96% [17,18,19,20]. The substantial difference in fluid load support predicted from theory between unconfined compression and other compressive loading configurations previously posed a conundrum regarding the functional role of cartilage interstitial fluid. However, it was later discovered from theory that tension-compression nonlinearity serves to considerably enhance fluid load support in articular cartilage [25,26]. According to the biphasic-CLE theory [25], the peak interstitial fluid load support in unconfined compression is given by

when analyzing a homogeneous layer of tissue, showing that fluid pressurization is enhanced by a greater ratio of tensile to compressive stiffness (H−A > > H−-A > λ2). For the inhomogeneous properties presented here, the use of this formula is approximate but may serve as a useful indicator of the expected peak magnitude of interstitial fluid load support. For the superficial tangential zone, the peak fluid load support would be estimated at 97% for the femur and 95% for the patella, which is in good agreement with the finite element contact results presented in Table 2. In the deep zone, in contrast, the fluid load support would be smaller, at 81% for the femur and 82% for the patella. Direct measurements of interstitial fluid load support in unconfined compression have recently confirmed these theoretical predictions, as well as the disparity in fluid pressurization at the articular surface versus subchondral bone interface [40].

The finite element contact analyses of the current study indicate that a homogeneous articular layer would produce its highest interstitial fluid pressure at the cartilage-bone interface, whereas an inhomogeneous layer produces interstitial fluid pressures of similar magnitudes at the bone and articular surface (Figure 3); furthermore, the interstitial fluid load support at the articular surface is greater in the inhomogeneous model (Table 2). It is believed that high interstitial fluid load support at the articular surface can promote low frictional coefficients [12,13,14,15,16], potentially contributing to the excellent wear properties of cartilage that are unmet by artificial bearing materials. Fluid load support helps maintain morphological integrity of the cartilage throughout life, despite heavy mechanical demands. According to our previously proposed model for the frictional response of articular cartilage [16,41], the time-dependence of the friction coefficient of cartilage, µeff, is predicated on the time-varying interstitial fluid load support according to the modeling equation

where µeq is the equilibrium friction coefficient achieved when Wp/W → 0, and φ is the fraction of the contact area over which solid to solid contact occurs between the porous bearing surfaces. This model predicts that the friction coefficient µeff achieves its smallest value when Wp/W is greatest. Even small differences in the peak value of Wp/W, as observed in this study, can have a significant influence on the minimum value, µmin. For example in the patella, according to the results of Table 2, the homogeneous model yields µmin/µeq = 0.11 whereas the inhomogeneous model yields µmin/µeq = 0.06, when φ = 0.04 (which corresponds to the contact of two cartilage layers, each with 20% solid content). Thus a change in Wp/W from 0.93 to 0.98 yields a factor of two decrease in µmin. Consequently, a higher interstitial fluid load support at the articular surface may be viewed as an optimal adaptation to the principal function of articular cartilage, which is to serve as a low friction bearing surface.

Furthermore, a high interstitial fluid load support contributes to the dynamic compressive stiffness of cartilage, thereby reducing tissue deformation under loading. While the equilibrium modulus of articular cartilage is on the order of 0.46 MPa (Table 1), the dynamic unconfined compression modulus under instantaneous loading is given by H−A + (H−A – 3λ2)/2 [25], corresponding to effective dynamic compressive moduli in the range of 4 to 8 MPa in the superficial zone of the patella and femur, and 2.4 MPa in the deeper zones. These dynamic moduli are smaller than those obtained from direct measurements (e.g., 12–20 MPa in bovine cartilage, [42,43]), because the biphasic-CLE theory predictions are based on small strain analysis and do not account for the nonlinear stiffening of cartilage in the range of tensile strains [4,44,45] and compressive strains [8,46,47], or the effects of intrinsic, flow-independent viscoelasticity of the solid matrix [26,48,49,50,51,52], all of which may need to be incorporated in a more refined model of the articular layer. It is for these reasons that the loads applied in the finite element analyses of this study (~150 N) remain sub-physiologic in order to maintain the peak strain magnitudes below 0.2 (Table 4), with contact stresses in the range 0.25–0.29 MPa. In contrast, physiologic contact forces in closed kinematic chain activities of the patellofemoral joint can be as high as 4,000 N [53], with contact stresses as high as 8 MPa.

The second hypothesis of this study focused on the distribution of elastic (or effective) stresses throughout the articular layer. In general, the finite element results did not indicate that inhomogeneous material properties of cartilage produce a more homogeneous stress, strain or strain-energy distribution through the depth of the tissue. Though some differences in distributions were observed between homogeneous and inhomogeneous models (notably in the minimum effective normal stress and in the peak magnitudes of effective stresses and strains), none of these observations fundamentally altered the finding that the stress distribution remains non-uniform through the depth of the articular layer in both cases. Consequently, the results of this study do not support the hypothesis that the depth-dependent inhomogeneous distribution of cartilage properties produces a more homogeneous state of stress. By showing that the peak values of the stresses are greater in the inhomogeneous model (Table 5), the results suggest that tissue inhomogeneity does not reduce stresses either. Conversely, inhomogeneity does produce lower peak strain magnitudes (Table 4), which may arguably represent its functional purpose. No statistical analysis is provided in the comparison of homogeneous and inhomogeneous models because the finite element results were obtained based on properties averaged from six human patellofemoral joints. In principle, it should be possible to generate separate homogeneous and inhomogeneous finite element models for each of the six joints and perform statistical comparisons on specific measures of stress inhomogeneity, such as the coefficients of variation for the principal normal effective and maximum effective shear stresses. However, this more onerous approach was not deemed justified based on the results presented above.

In biological tissues which are known to remodel in response to their mechanical environment, such as bone or muscle, investigators have proposed remodeling rules where the remodeling rate is a function of a mechanical signal, such as stress, strain energy density, or other. In such models, the remodeling proceeds until the mechanical signal is approximately uniform throughout the tissue. Thus, tissues that can remodel significantly in the presence of a mechanical signal such as stress, may evolve to exhibit a nearly uniform distribution of stress under normal loading conditions. In contrast, adult articular cartilage has very limited ability to remodel in response to mechanical signals, as evidenced for example in the lack of difference in cartilage thickness between athletes and sedentary subjects [54, 55]. This may represent a possible explanation as to why the depth-dependent inhomogeneous properties of cartilage are not functionally optimized to produce a uniform distribution of mechanical signals such as stress, strain, or strain energy density, unlike other biological tissues.

In our earlier contact analyses of biphasic cartilage layers representative of articular function [17,19,20], and in comparable studies by others [56,57], the solid matrix was modeled as linear and isotropic. It was found that the peak magnitudes of the principal normal and maximum shear stresses and strains all occurred at the cartilage-bone interface, away from the center of contact. In contrast, in the current study, peak tensile and shear stresses occur at the center of contact near the articular surface, whereas peak strains occur at the cartilage-bone interface away from the center of contact (Table 4). Compared with previous analyses, modeling the tension-compression nonlinearity of the cartilage solid matrix yields distinct qualitative and quantitative differences in the predicted response, when compared to linear isotropic models. The results of this study are qualitatively consistent with the findings of Donzelli et al. [58] and Garcia et al. [59], who used a linear biphasic transversely isotropic model of articular cartilage. Donzelli et al. also found that changing the curvature of the articular layers influences the patterns of stress distribution, a phenomenon that was not investigated in the current study. In a clinical context it is of importance to note that experimental studies of the impact response of articular cartilage [60,61] have demonstrated that fissures may appear both at the articular surface and at the cartilage-bone interface. This suggests that fissures at the articular surface may occur due to excessive tensile stresses, shear stresses, or strain-energy density, while failure at the cartilage-bone interface may occur due to excessive normal or shear strains [17,62].

In summary, the findings of this study show that material properties of articular cartilage vary substantially throughout the depth of the tissue, and that the depth-dependent inhomogeneity of the material properties of articular cartilage promotes higher interstitial fluid pressurization at the articular surface, where it may help reduce friction and wear. However, the depth-dependent inhomogeneity in material properties does not appear to promote greater uniformity in stresses, strains, or strain energy density through the thickness of the articular layer. These findings provide greater insight into the structure-function relationships in articular cartilage and help to understand how cartilage maintains appropriate mechanical function and morphological integrity throughout life, despite heavy mechanical usage.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported with funds from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (AR-43628, AR-46532).

Footnotes

Throughout the presentation of results, “maximum” and “minimum” refer to components of the strain or stress tensor at a point, whereas “peak” value refers to the greatest magnitude of that strain or stress component over the entire articular layer.

Contributor Information

Ramaswamy Krishnan, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Seonghun Park, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA.

Felix Eckstein, Institute of Anatomy, Ludwig Maximilians Universität, Munich, Germany.

Gerard A. Ateshian, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA

References

- 1.Meachim G, Stockwell RA. The matrix. In: Freeman MAR, editor. Adult Articular Cartilage. 2nd ed. Kent, England: Pitman Medical; 1979. pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mow VC, Ratcliffe A. Structure and Function of Articular Cartilage and Meniscus. In: Mow VC, Hayes WC, editors. Basic Orthopaedic Biomechanics. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maroudas A. Physicochemical properties of articular cartilage. In: Freeman MAR, editor. Adult Articular Cartilage. 2nd ed. Kent, England: Pitman Medical; 1979. pp. 215–290. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kempson GE. Mechanical properties of articular cartilage. In: Freeman MAR, editor. Adult Articular Cartilage. 2nd ed. Kent, England: Pitman Medical; 1979. pp. 333–414. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akizuki S, Mow VC, Muller F, Pita JC, Howell DS, Manicourt DH. Tensile properties of human knee joint cartilage: I. Influence of ionic conditions, weight bearing, and fibrillation on the tensile modulus. J. Orthop. Res. 1986;Vol. 4:379–392. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100040401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guilak F, Ratcliffe A, Mow VC. Chondrocyte deformation and local tissue strain in articular cartilage: a confocal microscopy study. J. Orthop. Res. 1995;Vol. 13:410–421. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100130315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schinagl RM, Gurskis D, Chen AC, Sah RL. Depth-dependent confined compression modulus of full-thickness bovine articular cartilage. J. Orthop. Res. 1997;Vol. 15:499–506. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100150404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen AC, Bae WC, Schinagl RM, Sah RL. Depth- and strain-dependent mechanical and electromechanical properties of full-thickness bovine articular cartilage in confined compression. J. Biomech. 2001;Vol. 34:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang CC-B, Chahine NO, Hung CT, Ateshian GA. Optical determination of anisotropic properties of bovine articular cartilage in compression. J. Biomech. Vol. 36:339–353. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00417-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brandt KD. Cartilage Changes in Osteoarthritis. Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University School of Medicine Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Humphrey JD, Na S. Elastodynamics and arterial wall stress. Ann. Biomed. Eng. Vol. 30:509–523. doi: 10.1114/1.1467676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCutchen CW. The frictional properties of animal joints. Wear. 1962;Vol 5:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malcom LL. Ph.D. Thesis. San Diego: University of California; 1976. An Experimental investigation of the frictional and deformational responses of articular cartilage interfaces to static and dynamic loading. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forster H, Fisher J. The influence of loading time and lubricant on the friction of articular cartilage. Proc. Instn. Mech. Engrs. 1996;Vol 210(Part H):109–119. doi: 10.1243/PIME_PROC_1996_210_399_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ateshian GA. A theoretical formulation for boundary friction in articular cartilage. J. Biomech. Eng. ASME. 1997;Vol 119:81–86. doi: 10.1115/1.2796069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ateshian GA, Wang H, Lai WM. The role of interstitial fluid pressurization and surface porosities on the boundary friction of articular cartilage. J. Tribology. 1998;Vol 120:241–251. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ateshian GA, Lai WM, Zhu WB, Mow VC. An asymptotic solution for two contacting biphasic cartilage layer. J. Biomech. 1994;Vol 27:1347–1360. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macirowski T, Tepic S, Mann RW. Cartilage stresses in the human hip joint. J. Biomech. Eng. 1994;Vol 116:11–18. doi: 10.1115/1.2895693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ateshian GA, Wang H. A theoretical solution for the rolling contact of frictionless cylindrical biphasic articular cartilage layers. J. Biomech. 1995;Vol 28:1341–1355. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelkar R, Ateshian GA. Contact creep of biphasic cartilage layers: Identical layers. J. App. Mech. ASME. 1999;Vol 66:137–145. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mow VC, Kuei SC, Lai WM, Armstrong CG. Biphasic creep and stress relaxation of articular cartilage in compression: Theory and experiments. J. Biomech. Eng. 1980;Vol 102:73–84. doi: 10.1115/1.3138202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizrahi J, Maroudas A, Lanir Y, Ziv I, Webber TJ. The 'instantaneous' deformation of cartilage: effects of collagen fiber orientation and osmotic stress. Biorheology. 1986;Vol. 23:311–330. doi: 10.3233/bir-1986-23402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen B, Lai WM, Mow VC. A transversely isotropic biphasic model for unconfined compression of growth plate and chondroepiphysis. J. Biomech. Eng. 1998;Vol. 120:491–496. doi: 10.1115/1.2798019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soulhat J, Buschmann MD, Shirazi-Adl A. A fibril-network-reinforced biphasic model of cartilage in unconfined compression. J. Biomech. Eng. 1999;Vol. 121:340–347. doi: 10.1115/1.2798330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soltz MA, Ateshian GA. A Conewise Linear Elasticity mixture model for the analysis of tension-compression nonlinearity in articular cartilage. J. Biomech. Eng. 2000;Vol. 122:576–586. doi: 10.1115/1.1324669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang CY, Mow VC, Ateshian GA. The role of flow-independent viscoelasticity in the biphasic tensile and compressive responses of articular cartilage. J. Biomech. Eng. Vol. 123:410–417. doi: 10.1115/1.1392316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li LP, Buschmann MD, Shirazi-Adl A. A fibril reinforced nonhomogeneous poroelastic model for articular cartilage: inhomogeneous response in unconfined compression. J. Biomech. 2000;Vol. 33:1533–1541. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heegaard J, Leyvraz PF, Curnier A, Rakotomanana L, Huiskes R. The biomechanics of the human patella during passive knee flexion. J. Biomech. 1995;Vol. 28:1265–1279. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00059-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bendjaballah MZ, Shirazi-Adl A, Zukor DJ. Finite element analysis of human knee joint in varus-valgus. Clin. Biomech. 1997;Vol. 12:139–148. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(97)00072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dunbar WL, Jr, Un K, Donzelli PS, Spilker RL. An evaluation of three-dimensional diarthrodial joint contact using penetration data and the finite element method. J. Biomech. Eng. 2001;Vol. 123:333–340. doi: 10.1115/1.1384876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li G, Lopez O, Rubash H. Variability of a three-dimensional finite element model constructed using magnetic resonance images of a knee for joint contact stress analysis. J. Biomech. Eng. 2001;Vol. 123:341–346. doi: 10.1115/1.1385841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donahue TL, Hull ML, Rashid MM, Jacobs CR. A finite element model of the human knee joint for the study of tibio-femoral contact. J. Biomech. Eng. Vol. 124:273–280. doi: 10.1115/1.1470171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wayne JS, Woo SL, Kwan MK. Application of the u-p finite element method to the study of articular cartilage. J. Biomech. Eng. 1991;Vol. 113:397–403. doi: 10.1115/1.2895418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Almeida ES, Spilker RL. Mixed and Penalty Finite Element Models for the Nonlinear Behavior of Biphasic Soft Tissues in Finite Deformation: Part I - Alternate Formulations. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 1997;Vol. 1:25–46. doi: 10.1080/01495739708936693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bathe K-J. Finite element procedures. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herberhold C, Faber S, Stammberger T, Steinlechner M, Putz R, Englmeier KH, Reiser M, Eckstein F. In situ measurements of articular cartilage deformation in intact femoropatellar joint under static loading. J. Biomech. 1999;Vol. 32:1287–1295. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oloyede A, Broom ND. Is classical consolidation theory applicable to articular cartilage deformation? Clin. Biomech. 1991;Vol. 6:206–212. doi: 10.1016/0268-0033(91)90048-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soltz MA, Ateshian GA. Experimental verification and theoretical prediction of cartilage interstitial fluid pressurization at an impermeable contact interface in confined compression. J. Biomech. 1998;Vol. 31:927–934. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00105-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Armstrong CG, Lai WM, Mow VC. An analysis of the unconfined compression of articular cartilage. J. Biomech. Eng. 1984;Vol. 106:165–173. doi: 10.1115/1.3138475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Park S, Krishnan R, Nicoll SB, Ateshian GA. Cartilage interstitial fluid load support in unconfined compression. J. Biomech. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00231-8. in review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krishnan R, Kopacz M, Ateshian GA. Verification of the role of interstitial fluid load support in the frictional response of bovine articular cartilage. 49th Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Research Society; 2003. Paper No. 0287. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim YJ, Bonassar LJ, Grodzinsky AJ. The Role of Cartilage Streaming Potential, Fluid Flow and Pressure in the Stimulation of Chondrocyte Biosynthesis During Dynamic Compression. J. Biomech. 1995;Vol. 28:1055–1066. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)00159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Buschmann MD, Kim YJ, Wong M, Frank E, Hunziker EB, Grodzinsky AJ. Stimulation of Aggrecan Synthesis in Cartilage Explants By Cyclic Loading Is Localized To Regions of High Interstitial Fluid Flow. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1999;366:1–7. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woo SL, Lubock P, Gomez MA, Jemmott GF, Kuei SC, Akeson WH. Large deformation nonhomogeneous and directional properties of articular cartilage in uniaxial tension. J. Biomech. 1979;Vol. 12:437–446. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(79)90028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li LP, Soulhat J, Buschmann MD, Shirazi-Adl A. Nonlinear analysis of cartilage in unconfined ramp compression using a fibril reinforced poroelastic model. Clin. Biomech. 1999;Vol. 14:673–682. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(99)00013-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kwan MK, Lai WM, Mow VC. A finite deformation theory for cartilage and other soft hydrated connective tissues--I. Equilibrium results. J. Biomech. 1990;Vol. 23:145–155. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(90)90348-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ateshian GA, Warden WH, Kim JJ, Grelsamer RP, Mow VC. Finite deformation biphasic material properties of bovine articular cartilage from confined compression experiments. J. Biomech. 1997;Vol. 30:1157–1164. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(97)85606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mak AF. The apparent viscoelastic behavior of articular cartilage--the contributions from the intrinsic matrix viscoelasticity and interstitial fluid flows. J. Biomech. Eng. 1986;Vol. 108:123–130. doi: 10.1115/1.3138591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Setton LA, Zhu W, Mow VC. The biphasic poroviscoelastic behavior of articular cartilage: role of the surface zone in governing the compressive behavior. J. Biomech. 1993;Vol. 26:581–592. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(93)90019-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu W, Mow VC, Koob TJ, Eyre DR. Viscoelastic shear properties of articular cartilage and the effects of glycosidase treatments. J. Orthop. Res. 1993;Vol. 11:771–781. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DiSilvestro MR, Suh JK. A cross-validation of the biphasic poroviscoelastic model of articular cartilage in unconfined compression, indentation, and confined compression. J. Biomech. 2001;Vol. 34:519–525. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(00)00224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang C-Y, Soltz MA, Kopacz M, Mow VC, Ateshian GA. Experimental verification of the role of intrinsic matrix viscoelasticity and tensioncompression nonlinearity in the biphasic response of cartilage in unconfined compression. J. Biomech. Eng. 2003;Vol. 125:84–93. doi: 10.1115/1.1531656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen ZA, Roglic H, Grelsamer RP, Henry JH, Levine WN, Mow VC, Ateshian GA. Patellofemoral stresses during open and closed kinetic chain exercises: An analysis using computer simulation. Am. J. Sprots Med. 2001;Vol. 29:480–487. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290041701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mühlbauer R, Lukasz S, Faber S, Stammberger T, Eckstein F. Comparison of knee joint cartilage thickness in triathletes and physically inactive volunteers - 3D analysis with magnetic imaging. Am. J. Sports Med. 2000;Vol. 28:541–546. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280041601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eckstein F, Faber S, Muhlbauer R, Hohe J, Englmeier KH, Reiser M, Putz R. Functional adaptation of human joints to mechanical stimuli. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2002;Vol. 10:44–50. doi: 10.1053/joca.2001.0480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu JZ, Herzog W, Epstein M. An improved solution for the contact of two biphasic cartilage layers. J. Biomech. 1997;Vol. 30:371–375. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(96)00148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wu JZ, Herzog W, Epstein M. Joint contact mechanics in the early stages of osteoarthritis. Med. Eng. Phys. 2000;Vol. 22:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s1350-4533(00)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Donzelli PS, Spilker RL, Ateshian GA, Mow VC. Contact analysis of biphasic transversely isotropic cartilage layers and correlations with tissue failure. J. Biomech. 1999;Vol. 32:1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00106-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garcia JJ, Altiero NJ, Haut RC. An approach for the stress analysis of transversely isotropic biphasic cartilage under impact load. J. Biomech. Eng. Vol. 120:608–613. doi: 10.1115/1.2834751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thompson RC, Jr, Oegema TR, Jr, Lewis JL, Wallace L. Osteoarthrotic changes after acute transarticular load. An animal model. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1991;Vol. 73A:990–1001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Atkinson PJ, Haut RC. Injuries produced by blunt trauma to the human patellofemoral joint vary with flexion angle of the knee. J. Orthop. Res. 2001;Vol. 19:827–833. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)00073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Atkinson TS, Haut RC, Altiero NJ. An investigation of biphasic failure criteria for impact-induced fissuring of articular cartilage. J. Biomech. Eng. Vol. 120:536–537. doi: 10.1115/1.2798025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]