Abstract

Ophthalmologic abnormalities have been described in patients with dementia, but the extent to which poor vision and treatment for visual disorders affect cognitive decline is not well defined. Linked data from the Health and Retirement Study and Medicare files (1992–2005) were used to follow the experiences of 625 elderly US study participants with normal cognition at baseline. The outcome was a diagnosis of dementia, cognitively impaired but no dementia, or normal cognition. Poor vision was associated with development of dementia (P = 0.0048); individuals with very good or excellent vision at baseline had a 63% reduced risk of dementia (95% confidence interval (CI): 20, 82) over a mean follow-up period of 8.5 years. Participants with poorer vision who did not visit an ophthalmologist had a 9.5-fold increased risk of Alzheimer disease (95% CI: 2.3, 39.5) and a 5-fold increased risk of cognitively impaired but no dementia (95% CI: 1.6, 15.9). Poorer vision without a previous eye procedure increased the risk of Alzheimer disease 5-fold (95% CI: 1.5, 18.8). For Americans aged 90 years or older, 77.9% who maintained normal cognition had received at least one previous eye procedure compared with 51.7% of those with Alzheimer disease. Untreated poor vision is associated with cognitive decline, particularly Alzheimer disease.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease; delirium, dementia, amnestic, cognitive disorders; dementia; health services research; Medicare; memory disorders; ophthalmology; vision disorders

Cloudy, sensitive, or reduced vision can be disorienting. There is an extensive record of the intersection between eye pathologies and dementia in both the ophthalmologic and psychiatric literature (1, 2). Visual disturbances have been described as one of the first symptoms presenting in persons with Alzheimer disease, including problems such as contrast sensitivity, visuospatial orientation, color perception, and pupil reaction (3–8). Macular degeneration, retinal disorders, and problems with visual acuity have also been associated with cognitive impairment in various studies (9–11).

Although often not studied, it is possible that such ocular disturbances may be precursors—not consequences—of cognitive decline. Prospective studies have shown that visual impairment predicts cognitive decline, although uncertainty remains whether treatment for visual problems could delay such decline (12–14). In this study, we sought to address the following 2 questions: Is poor vision an etiologic contributor to dementia? Does treatment of visual disorders affect the probability of developing dementia? Using data collected prior to and after the diagnosis of dementia, we attempted to shed light on these questions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects were US individuals who participated in the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study, a sample from the nationally representative Health and Retirement Study (15). Only those persons who had normal cognition at baseline (i.e., during their initial Health and Retirement Study interview) were included in this investigation. Normal cognition was defined as a score of 14–35 on the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status test for self-respondents (n = 606 subjects) or a score of 1.00–3.34 on the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly for proxy respondents (n = 19) (16). The Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status has been found to be a valid measure for assessing cognitive function (17–19). Persons with cognitive impairment or dementia at baseline were excluded. This exclusion yielded 625 subjects who were followed for 3.5–13 years (mean, 10.1 years; median, 10.9 years) during 1992–2005 by using a retrospective cohort design.

Measures

Data from the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study subjects were linked to Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services files (1992–2005). Berenson Eggers Type of Service codes in the Carrier files were used to determine the types of services received. These codes were developed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to group similar types of procedures into clinical categories to enhance analyses of Medicare data. Carrier files contain claims submitted by noninstitutional providers such as physicians and physician assistants, as well as freestanding ambulatory surgical centers. Surgical eye procedures included corneal transplant, cataract removal/lens insertion, retinal detachment, treatment of retinal lesions, and others. Diagnosis codes from the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, were used to identify disorders of the eye and adnexa (codes 360xx–379xx).

Data were also obtained regarding baseline vision during the 1992–1993 waves of the Health and Retirement Study from 606 respondents and 19 proxy respondents. Vision was measured on a 6-point scale (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor, blind); subjects who wore glasses rated their vision when using their glasses. In latter statistical analyses, the categories excellent and very good were combined to indicate “better vision,” with the remaining categories indicating “worse vision.”

Information was extracted from the Health and Retirement Study regarding other potential risk factors for dementia (20) such as age; gender; race (Caucasian, African American, other); highest educational level (grades 1–11, high school, some college, college graduate, postcollege); and history of high blood pressure, stroke, diabetes mellitus, and heart disease. The number of apolipoprotein E ϵ4 alleles was obtained from a buccal swab DNA sample; information regarding apolipoprotein E was missing for 6 participants, so best-subset regression was used to impute these values. Previous head injury was ascertained by emergency room visits for head-related principal diagnoses (i.e., reason for the visit) from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Inpatient and Outpatient Standard Analytical Files.

Outcome

All 625 subjects were assessed for cognitive status by an expert panel of neuropsychologists, neurologists, geropsychiatrists, and internists (15). A diagnosis of dementia, cognitively impaired but no dementia (CIND), or normal cognition was determined by consensus of this panel. The clinical assessment began with in-home administration of multiple neuropsychological tests by a psychometrician, medical history, assessment of medication use, and current behavioral and psychiatric symptoms. A videotaped neurologic examination was also performed. The final diagnosis of dementia was based on criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (21, 22).

This investigation was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan and the Privacy Board at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Statistical analyses

Results were weighted to account for the sampling design of the study and therefore reflect estimates of effect for the reference population (Americans aged ≥71 years). For bivariate analyses of categorical data, the design-based Pearson's chi-square test was used. Cumulative incidence of dementia was estimated since change from normal cognition to dementia during a specific time period was known. Survey-weighted multinomial logistic regression was used to evaluate the relation of eye-related services and diagnoses to cognitive status (normal, CIND, dementia). For analyses of Alzheimer disease, the outcome was coded as normal, CIND, or Alzheimer disease, with exclusion of other types of dementia. Adjustment was made for age (year of birth, centered), gender, race, education, number of apolipoprotein E ϵ4 alleles, previous head injury, diabetes mellitus, stroke, hypertension, and heart disease. The number needed to treat to prevent one case of dementia was calculated by using the fully adjusted model (covariates listed above) both for an eye procedure and a visit to an ophthalmologist. Analyses were conducted with Stata/SE 10.0 software (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas). The estimate of effect for multinomial logistic regression in Stata was calculated as a relative risk ratio, also referred to as a conditional odds ratio (23). Alpha was set at 0.05, 2-tailed.

Because vision problems have been associated with injuries and accidents (24), emergency department visits for injuries or accidents (occurring prior to the outcome) were extracted by using E codes in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Inpatient and Outpatient files. Rates of such injuries and accidents (per person-year) were calculated, as were exact P values for differences between cognitive groups.

In January 2002, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services initiated coverage for glaucoma screening in beneficiaries with diabetes mellitus, those with a family history of glaucoma, African Americans aged 50 years or older, and Hispanic Americans aged 65 years or older (25). Because data for certain high-risk individuals (non-Caucasians and those with a history of diabetes mellitus) were available, the services they received were compared before and after the program commenced.

RESULTS

Participants

Of the 625 subjects with normal cognition at baseline, 168 developed dementia, 169 developed CIND, and 288 remained cognitively normal. The corresponding survey-weighted percentages were 68.1% for normal cognition (95% confidence interval (CI): 64.8, 71.3), 21.1% for CIND (95% CI: 17.4, 25.3), and 10.8% for dementia (95% CI: 8.6, 13.4). The characteristics of the subjects are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Subjects by Later Cognitive Status, Elderly in the United States, 1992–2005

| Characteristic | Normal Cognition |

CIND |

Dementia |

|||

| Percenta | 95% CIa | Percenta | 95% CIa | Percenta | 95% CIa | |

| Age ≥85 yearsb | 12.6 | 9.3, 16.8 | 28.7 | 21.1, 37.7 | 31.9 | 23.6, 41.4 |

| Female | 61.6 | 55.4, 67.4 | 52.0 | 41.5, 62.4 | 70.2 | 60.8, 78.2 |

| Non-Caucasian | 6.5 | 4.1, 10.0 | 10.0 | 5.7, 16.9 | 8.3 | 4.6, 14.4 |

| <12 years of education | 26.8 | 22.1, 32.2 | 39.3 | 31.0, 48.4 | 35.3 | 26.2, 45.6 |

| Apolipoprotein Eϵ4 allele present | 23.1 | 17.0, 30.7 | 27.6 | 18.6, 38.9 | 36.5 | 27.6, 46.5 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 17.2 | 12.0, 24.1 | 27.4 | 19.2, 37.6 | 15.8 | 8.2, 28.3 |

| High blood pressure | 62.8 | 53.6, 71.2 | 57.8 | 48.6, 66.4 | 55.7 | 44.4, 66.5 |

| Heart disease | 23.5 | 18.6, 29.2 | 45.9 | 35.6, 56.5 | 45.7 | 36.5, 55.3 |

| Stroke | 7.0 | 4.3, 11.1 | 21.3 | 14.7, 30.0 | 36.6 | 24.6, 50.6 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CIND, cognitively impaired but no dementia.

Survey-weighted.

At time of outcome assessment.

Vision at baseline

Poorer vision at baseline was more prevalent in those who eventually were diagnosed with either cognitive impairment or dementia (Table 2). Only 9.7% of individuals who developed dementia had excellent vision at baseline, whereas 30.7% of those whose cognition remained normal had excellent baseline vision. When this 6-level vision scale was regressed on the outcome, the relative risk ratios were 1.52 (95% CI: 1.12, 2.04) for dementia and 1.28 (95% CI: 0.92, 1.77) for CIND when compared with normal cognition in the fully adjusted model. That is, the risk of dementia increased by 52% with each 1-unit increase in the vision scale (minimum, excellent vision; maximum, blind). The mean number of years between the baseline vision assessment and the outcome date was 8.5 years (standard deviation, 2.4), and the median was 9.3 years.

Table 2.

Vision at Baseline by Later Cognitive Status, Elderly in the United States, 1992–2005

| Vision at Baseline | Normal Cognition |

CIND |

Dementia |

P Value | |||

| Percenta | 95% CIa | Percenta | 95% CIa | Percenta | 95% CIa | ||

| Excellent | 30.7 | 22.5, 40.3 | 14.5 | 9.9, 20.8 | 9.7 | 5.4, 16.7 | |

| Very good | 29.5 | 21.7, 38.8 | 27.2 | 18.1, 38.7 | 20.7 | 13.8, 30.0 | |

| Good | 28.4 | 21.8, 36.0 | 37.3 | 26.9, 48.9 | 45.0 | 34.1, 56.4 | |

| Fair | 9.0 | 5.4, 14.7 | 17.9 | 10.9, 27.9 | 20.2 | 12.2, 31.6 | |

| Poor | 2.4 | 0.7, 7.4 | 2.9 | 0.6, 12.8 | 4.1 | 1.8, 9.3 | |

| Blind | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.0, 2.3 | 0.3 | 0.0, 2.3 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0.0048 | |||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CIND, cognitively impaired but no dementia.

Survey-weighted.

There was no difference in the use of glasses or contact lenses between cognitive groups at baseline (P = 0.115). Ninety-three percent of participants with normal cognition wore glasses or contact lenses; the comparable percentages for those with CIND and dementia were 91.7% and 86.0%, respectively.

In a secondary analysis, we assessed whether baseline vision was associated with number of apolipoprotein E ϵ4 alleles. We found that it was not (P = 0.294).

Eye procedures and diagnoses prior to outcome

Prior to the outcome date, 41.7% of participants received at least one eye procedure (95% CI: 36.5, 47.2), 76.9% visited an ophthalmologist at least once (95% CI: 72.3, 81.0), and 78.0% had at least one recorded diagnosis of an eye disorder (95% CI: 73.3, 82.1). The mean number of years from the ophthalmologist visit to the outcome date was 7.1 (standard deviation, 4.0), with a median of 7.4 years.

We found a significant association between prior eye-related services and dementia (Table 3). The risk of developing dementia was 56% lower for participants who had an eye procedure compared with those who did not. The risk of dementia was reduced 64% for those subjects who had at least one visit to an ophthalmologist compared with individuals who did not visit an ophthalmologist. Subjects with a previous diagnosis of an eye disorder had half the risk of dementia as those without such a diagnosis (relative risk ratio (RRR) = 0.49). The risk of dementia decreased by 10% with each visit to an ophthalmologist, decreased by 18% for each eye procedure, and decreased by 6% for each eye-related diagnosis. However, there was no difference in services received for hearing and speech by cognitive status, nor was there a difference in the number of medical office visits.

Table 3.

Relative Risk Ratios for Prior Eye-related Services and Cognitive Outcomes, Elderly in the United States, 1992–2005

| Prior Events | CIND |

Dementia |

||||

| RRRa | 95% CI | P Value | RRRa | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Eye procedure (yes/no) | 0.70 | 0.38, 1.30 | 0.249 | 0.44 | 0.23, 0.83 | 0.013 |

| No. of eye procedures | 0.97 | 0.81, 1.17 | 0.769 | 0.82 | 0.69, 0.97 | 0.025 |

| Visit with an ophthalmologist (yes/no) | 0.63 | 0.31, 1.29 | 0.199 | 0.36 | 0.23, 0.57 | <0.001 |

| No. of visits to an ophthalmologist | 0.97 | 0.95, 1.00 | 0.050 | 0.90 | 0.87, 0.94 | <0.001 |

| Echography of the eye (yes/no) | 0.76 | 0.45, 1.29 | 0.297 | 0.66 | 0.38, 1.14 | 0.132 |

| Diagnosis of an eye disorder (yes/no) | 0.82 | 0.38, 1.80 | 0.610 | 0.49 | 0.27, 0.89 | 0.021 |

| No. of diagnoses of eye disorders | 0.98 | 0.96, 1.00 | 0.075 | 0.94 | 0.91, 0.97 | <0.001 |

| Excellent or very good vision at baseline | 0.60 | 0.29, 1.24 | 0.157 | 0.37 | 0.18, 0.80 | 0.014 |

| Hearing and speech services | 1.12 | 0.61, 2.06 | 0.696 | 1.21 | 0.60, 2.44 | 0.572 |

| No. of medical office visits (total) | 1.00 | 0.99, 1.01 | 0.951 | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.01 | 0.335 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CIND, cognitively impaired but no dementia; RRR, relative risk ratio.

Reference group was subjects with normal cognition. Results were adjusted for age, gender, race, education, number of apolipoprotein E ϵ4 alleles, head injury, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, and heart disease.

Restriction of the data to only those subjects followed for at least 6 years prior to the outcome did not appreciably change these results. The risk of dementia was halved (RRR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.26, 0.95) for those who had received a prior eye procedure. The risk decreased by 17% for each eye procedure (RRR = 0.83, 95% CI: 0.70, 1.00; P = 0.046). The risk of dementia decreased by 59% (RRR = 0.41, 95% CI: 0.25, 0.67) for those who visited an ophthalmologist. The risk decreased by 8% (RRR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.90, 0.95) for every visit to an ophthalmologist. The comparable relative risk ratios were 0.51 (95% CI: 0.27, 0.96) for an eye-related diagnosis and 0.95 (95% CI: 0.92, 0.98) for number of eye-related diagnoses.

When the analyses were restricted to those subjects who did not have vascular disease (n = 540), the results were similar. The risk of nonvascular dementia was reduced by 64% (RRR = 0.36, 95% CI: 0.17, 0.74) for those who had at least one eye procedure. The risk of nonvascular dementia was reduced by 66% (RRR = 0.34, 95% CI: 0.20, 0.60) for subjects who visited an ophthalmologist at least once. For each eye procedure, the risk of nonvascular dementia decreased by 18% (RRR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.67, 0.99), and, for each visit to an ophthalmologist, the risk of nonvascular dementia decreased by 10% (RRR = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.86, 0.94). The risk of nonvascular dementia decreased by 52% if the participant had at least one eye-related diagnosis (RRR = 0.48, 95% CI: 0.26, 0.87). For each eye diagnosis, the risk of nonvascular dementia decreased by 7% (RRR = 0.93, 95% CI: 0.90, 0.96).

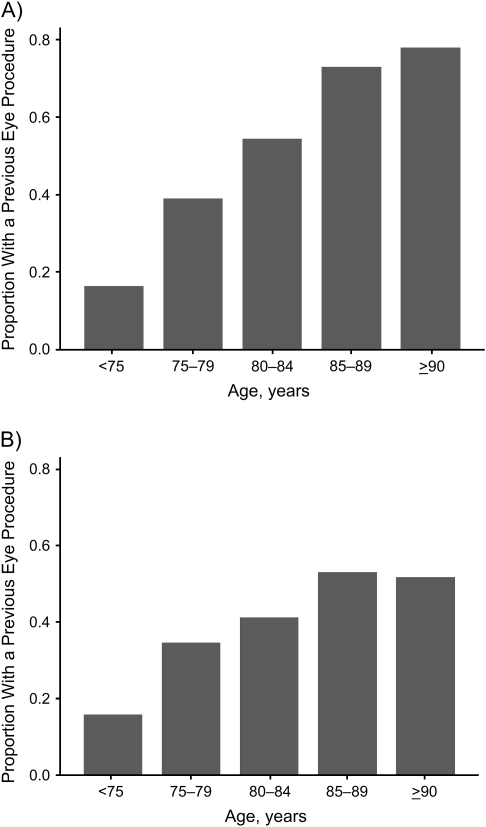

Proportions of elderly Americans who received an eye procedure prior to the outcome are shown in Figure 1. Although the proportion receiving an eye procedure increased with age for both cognitive groups, the increase was more marked for those whose cognition remained normal (P < 0.001). For Americans 90 years of age or older who developed Alzheimer disease, 51.7% received at least one previous eye procedure (a mean of 7 years prior to the outcome); this finding compared with 77.9% for Americans of similar age with normal cognition.

Figure 1.

Proportion of the US population who received a previous eye procedure by age (years) and cognitive status, 1992–2005. A) normal cognition; B) Alzheimer disease.

Vision at baseline with and without treatment

The possible effect of treatment on individuals with poor vision was examined, and the results are shown in Table 4. Failure to visit an ophthalmologist increased the risk of Alzheimer disease 9-fold for those with worse vision and increased the risk of CIND 5-fold. However, for those with worse vision who visited an ophthalmologist, the risk of cognitive decline was not significantly elevated. In addition, the risk of Alzheimer disease was 5 times greater for those with worse vision who had no previous eye procedure (RRR = 5.35), but it was also elevated for individuals with worse vision who had an eye procedure (RRR = 2.52).

Table 4.

Relative Risk Ratios for Prior Eye-related Services, Baseline Vision, and Cognitive Outcomes, Elderly in the United States, 1992–2005

| Prior Events | CIND |

Alzheimer disease |

||||

| RRRa | 95% CI | P Value | RRRa | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Better vision and visit to an ophthalmologist | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| Better vision and no visit to an ophthalmologist | 2.33 | 0.71, 7.63 | 0.156 | 2.40 | 0.66, 8.70 | 0.176 |

| Worse vision and visit to an ophthalmologist | 1.63 | 0.79, 3.35 | 0.176 | 1.99 | 0.78, 5.10 | 0.144 |

| Worse vision and no visit to an ophthalmologist | 5.05 | 1.61, 15.89 | 0.007 | 9.46 | 2.26, 39.51 | 0.003 |

| Better vision and eye procedure | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||||

| Better vision and no eye procedure | 1.64 | 0.52, 5.14 | 0.381 | 2.92 | 0.82, 10.38 | 0.094 |

| Worse vision and eye procedure | 2.11 | 0.95, 4.70 | 0.066 | 2.52 | 1.03, 6.16 | 0.044 |

| Worse vision and no eye procedure | 2.28 | 0.91, 5.69 | 0.076 | 5.35 | 1.52, 18.82 | 0.011 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CIND, cognitively impaired but no dementia; RRR, relative risk ratio.

Reference group was subjects with normal cognition. Results were adjusted for age, gender, race, education, number of apolipoprotein E ϵ4 alleles, head injury, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, and heart disease.

When the analyses shown in Table 4 were restricted to only those persons followed for at least 6 years prior to the outcome, the results did not materially change. The relative risk ratio for participants with worse vision who did not visit an ophthalmologist was 8.50 (95% CI: 1.85, 39.15; P = 0.008) for Alzheimer disease compared with normal cognition. For CIND, the comparable relative risk ratio was 4.60 (95% CI: 1.40, 15.12; P = 0.014). The relative risk ratio for Alzheimer disease in persons with worse vision who had a previous eye procedure was 2.29 (95% CI: 0.99, 5.30; P = 0.054). The relative risk ratio for those with worse vision and no eye procedure was 5.17 (95% CI: 1.60, 16.74; P = 0.008) for Alzheimer disease; the comparable relative risk ratio for CIND was 2.22 (95% CI: 0.91, 5.45; P = 0.079).

Eye services before and after outcome

We investigated whether there was a difference in the receipt of eye services before and after diagnosis of Alzheimer disease (Table 5). Persons with Alzheimer disease had a significantly reduced risk of an eye procedure prior to onset of this disease (59% reduction in risk), but they were just as likely as those with normal cognition to have an eye procedure afterward. The risk of Alzheimer disease was reduced 65% with a previous visit to an ophthalmologist. After diagnosis of Alzheimer disease, however, patients with Alzheimer disease were just as likely to visit an ophthalmologist as those patients with normal cognition. While participants who developed Alzheimer disease were less likely than those with normal cognition to have had eye-related services and diagnoses prior to the onset of disease, they were just as likely to have such services or diagnoses afterward.

Table 5.

Relative Risk Ratios for Eye-related Services and Alzheimer Disease Before and After Diagnosis, Elderly in the United States, 1992–2005

| Events | Before Diagnosis |

After Diagnosis |

||||

| RRRa | 95% CI | P Value | RRRa | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Eye procedure (yes/no) | 0.41 | 0.19, 0.87 | 0.022 | 1.87 | 0.87, 4.01 | 0.102 |

| No. of eye procedures | 0.84 | 0.69, 1.02 | 0.083 | 1.17 | 0.95, 1.45 | 0.126 |

| Visit to an ophthalmologist (yes/no) | 0.35 | 0.17, 0.73 | 0.007 | 0.95 | 0.49, 1.82 | 0.861 |

| No. of visits to an ophthalmologist | 0.89 | 0.84, 0.95 | 0.001 | 0.97 | 0.89, 1.04 | 0.371 |

| Diagnosis of an eye disorder (yes/no) | 0.43 | 0.19, 0.95 | 0.038 | 1.25 | 0.66, 2.39 | 0.482 |

| No. of diagnoses with eye disorders | 0.92 | 0.88, 0.97 | 0.001 | 1.02 | 0.97, 1.08 | 0.360 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CIND, cognitively impaired but no dementia; RRR, relative risk ratio.

The reference group was subjects with normal cognition. Results were adjusted for age, gender, race, education, number of apolipoprotein E ϵ4 alleles, head injury, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke, and heart disease.

High-risk populations

There were 180 high-risk subjects in this study. These individuals were significantly more likely to have poorer vision at baseline than those not at high risk (P = 0.001 for the 6-point vision scale). Visits to an ophthalmologist increased in this population, from 2.2/100 person-years before Medicare coverage began in 2002 to 14.6/100 person-years afterward (P < 0.001). Eye procedures in high-risk patients also increased, from 1.3/100 person-years before Medicare coverage to 10.8/100 person-years afterward (P < 0.001).

Other evidence of visual problems

As ancillary evidence of prior vision problems, participants who developed dementia had 1.95 emergency room visits for injuries or accidents per 100 person-years prior to diagnosis compared with 0.78 for those with normal cognition (P = 0.0014). Persons with CIND had 1.49 such visits per 100 person-years (P = 0.0214 when compared with normal cognition).

Number needed to treat

If the association between treatment for visual problems and dementia were causal, the number needed to treat with an eye procedure to prevent one case of dementia was 6 during the mean follow-up period of 7.1 years (median, 7.4 years). The number needed to treat with an ophthalmologist visit to prevent one case of dementia was 4 during this follow-up period.

DISCUSSION

Persons diagnosed with late-life dementia, particularly those with Alzheimer disease, had poorer vision and received fewer ophthalmologic services prior to their diagnosis than those who aged with normal cognition. The results not only indicate an association between poor vision and Alzheimer disease but also suggest that treatment of visual problems may affect the probability of developing Alzheimer disease. It is possible that underdiagnosis or undertreatment of visual problems in the elderly may contribute to cognitive decline.

Our study provides evidence that the visual problems preceded the symptoms of cognitive decline. We are not alone in this supposition. In the Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing, visual acuity significantly affected memory decline in 2,087 older individuals over a 2-year period (12). Their data indicated that vision, not hearing, was associated with memory decline. In a prospective cohort study of 1,668 women, poor visual acuity was associated with cognitive decline measured an average of 4.4 years later (13). Similarly, their results showed that visual impairment predicted cognitive decline to a greater extent than hearing. In a longitudinal study of 2,140 Mexican Americans, impairment of near vision predicted cognitive decline (using the Mini-Mental State Examination for the blind) in the 7 years after assessment (14). In the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, performance on the Benton Visual Retention Test, which measures visual perception, vision memory, and visuoconstructive abilities, was significantly predictive of Alzheimer disease up to 15 years after testing (26). In an earlier study, this vision test predicted cognitive impairment in the 6 years prior to the onset of Alzheimer disease (27). Moreover, in a study of autopsied patients, subjects who had poorer performance on the Benton Visual Retention Test had cerebral amyloid deposition consistent with Alzheimer disease 20 years later (28).

Specific visual disorders have been shown to share common pathogenic pathways with Alzheimer disease. Amyloid-β deposition was found more often in drusen of individuals with age-related macular degeneration than in those without this condition; the authors suggested a common pathophysiology (29). Similar Alzheimer disease–related pathology has been found in asymptomatic elderly within the Edinger-Westphal nucleus, which controls pupillary function (30). Furthermore, amyloid-β deposits were formed in a time- and dose-dependent manner after induction of glaucoma using an animal model (31). Upon challenge with treatments that specifically targeted the amyloid-β pathway, significantly less retinal cell death was observed, suggesting that amyloid-β may etiologically contribute to glaucoma (31).

While some studies indicate that visual dysfunction may originate within the visual cortex, others suggest correctable problems with the eye itself. Whether treatment of specific visual disorders could alleviate cognitive decline deserves further investigation. In a study of 100 patients, memory and learning were shown to improve significantly after cataract surgery (32). Improvement in cognition after cataract surgery was also reported in a prospective study of elderly patients in Japan (33). However, in a study of elderly subjects with 1 year of follow-up, cognition improved for individuals with cataracts—both those with and without cataract surgery (34).

The results of this study suggest that, whatever visual impairments existed, eye-related services may have delayed the date on which the individual met the definition of dementia. It is possible that, if visual problems and functional disabilities associated with poor vision accrued over time, an individual could meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, criteria for Alzheimer disease and exhibit impairment in multiple domains at an earlier point in life. Moreover, the extent to which aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, and memory impairment can be adequately assessed with concomitant visual problems has not yet been fully explored.

Ancillary evidence is provided by factors reported to reduce the risk of dementia, including physical activity and mental stimulation—both of which may be impacted by visual loss. The presence of a visual disorder may impede one's mobility and affect the types of activities associated with a reduced risk of Alzheimer disease, such as reading and playing board games and musical instruments (35). Visual problems may also influence the extent of social interactions and networking; the pathology underlying Alzheimer disease has been found to be modified by social networking (36).

Although there was no significant difference in the use of glasses or contact lenses at baseline, there was an association with vision. This finding could indicate that, whatever visual disorders existed at that time, glasses could not correct for these deficiencies. Alternatively, it may indicate that the glasses being utilized by some subjects did not adequately correct problems with visual acuity (e.g., an outdated prescription). Corroborating evidence from this data set indicates that injury-related visits to the emergency room were more frequent prior to the diagnosis of dementia or CIND; prior studies have shown a strong association between poor vision and injuries/accidents (24).

These findings are limited by the observational nature of the study. Specific testing for vision was not conducted at uniform intervals during the time period prior to diagnosis of dementia or CIND. Survival bias could have impacted the results of this study, although survival rates would be expected to be lower among those with poorer vision, persons who do not receive as many health services, and those with cognitive impairments. Therefore, inclusion of such subjects could pull the estimates of effect farther from the null. Furthermore, an argument could be made that cognitive impairment may have been apparent prior to the diagnosis and, therefore, patients or physicians selectively underused eye-related services because of this impairment. Several factors refute this proposition. First, the cohort was restricted to those with evidence of normal cognition at baseline. Second, there was no difference in the number of medical office visits or the use of hearing and speech services among the 3 cognitive groups. That is, patients were not underutilizing other services. Third, after dementia was diagnosed, participants were just as likely to have eye-related services as those with normal cognition.

We were unable to ascertain medication use and, as such, the spectrum of various eye treatments was not adequately covered in this data set. We suspect that the stronger association between Alzheimer disease and poor vision without a prior ophthalmologist visit (RRR = 9.46) may be due to the fact that visiting an ophthalmologist may serve as a surrogate for the prescription of either an eye medication and/or an eye procedure, whichever was appropriate for the given condition.

One international task force has already formally proposed including vision testing within a comprehensive consultation to prevent dementia in the elderly (37). Since routine eye screening is not currently covered for Medicare beneficiaries, we encourage an investigation of the cost-effectiveness of providing Medicare coverage for at least one vision screening for beneficiaries to postpone cognitive decline later in life.

In conclusion, poor vision is associated with late-life dementia. Our study results suggest that treatment of visual disorders may delay the diagnosis of dementia, particularly Alzheimer disease.

Acknowledgments

Author affiliations: Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Mary A. M. Rogers, Kenneth M. Langa); Veterans Affairs Center for Practice Management and Outcomes Research, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Kenneth M. Langa); and Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan (Kenneth M. Langa).

The National Institute on Aging provided funding for the Health and Retirement Study and the Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study (U01 AG09740), from which data were used for this analysis. The Health and Retirement Study is performed at the Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. Additional support was provided by grants from the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG027010 and R01 AG030155).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- CIND

cognitively impaired but no dementia

- RRR

relative risk ratio

References

- 1.Holroyd S, Shepherd ML. Alzheimer's disease: a review for the ophthalmologist. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;45(6):516–524. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cronin-Golomb A, Hof PR, editors. Vision in Alzheimer’s Disease. (Interdisciplinary Topics in Gerontology, vol 34) Basel, Switzerland: S Karger AG Publishers; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cogan DG. Visual disturbances with focal progressive dementing disease. Am J Ophthalmol. 1985;100(1):68–72. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74985-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cormack FK, Tovee M, Ballard C. Contrast sensitivity and visual acuity in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(7):614–620. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200007)15:7<614::aid-gps153>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cronin-Golomb A, Corkin S, Growdon JH. Visual dysfunction predicts cognitive deficits in Alzheimer's disease. Optom Vis Sci. 1995;72(3):168–176. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199503000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kavcic V, Fernandez R, Logan D, et al. Neurophysiological and perceptual correlates of navigational impairment in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2006;129(pt 3):736–746. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mapstone M, Dickerson K, Duffy CJ. Distinct mechanisms of impairment in cognitive ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2008;131(pt 6):1618–1629. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fotiou DF, Brozou CG, Haidich AB, et al. Pupil reaction to light in Alzheimer's disease: evaluation of pupil size changes and mobility. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19(5):364–371. doi: 10.1007/BF03324716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemons TE, Rankin MW, McBee WL, et al. Cognitive impairment in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study: AREDS report no. 16. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(4):537–543. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.4.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding J, Patton N, Deary IJ, et al. Retinal microvascular abnormalities and cognitive dysfunction: a systematic review. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(8):1017–1025. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.141994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uhlmann RF, Larson EB, Koepsell TD, et al. Visual impairment and cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer's Disease. J Gen Intern Med. 1991;6(2):126–132. doi: 10.1007/BF02598307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anstey KJ, Luszcz MA, Sanchez L. Two-year decline in vision but not hearing is associated with memory decline in very old adults in a population-based sample. Gerontology. 2001;47(5):289–293. doi: 10.1159/000052814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin MY, Gutierrez PR, Stone KL, et al. Vision impairment and combined vision and hearing impairment predict cognitive and functional decline in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(12):1996–2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reyes-Ortiz CA, Kuo YF, Dinuzzo AR, et al. Near vision impairment predicts cognitive decline: data from the Hispanic Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):681–686. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langa KM, Plassman BL, Wallace RB, et al. The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study: study design and methods. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(4):181–191. doi: 10.1159/000087448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herzog AR, Wallace RB. Measures of cognitive functioning in the AHEAD Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52(spec no):37–48. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.special_issue.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crooks VC, Clark L, Petitti DB, et al. Validation of multi-stage telephone-based identification of cognitive impairment and dementia [electronic article] BMC Neurol. 2005;5(1):8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barber M, Stott DJ. Validity of the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) in post-stroke subjects. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(1):75–79. doi: 10.1002/gps.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Jager CA, Budge MM, Clarke R. Utility of TICS-M for the assessment of cognitive function in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003;18(4):318–324. doi: 10.1002/gps.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patterson C, Feightner J, Garcia A, et al. General risk factors for dementia: a systematic evidence review. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(4):341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III-R. 3rd ed, rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gould W. Interpreting logistic regression in all its forms. Stata Tech Bull. 2000;STB-53:26–29. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Legood R, Scuffham P, Cryer C. Are we blind to injuries in the visually impaired? A review of the literature. Inj Prev. 2002;8(2):155–160. doi: 10.1136/ip.8.2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Instructions for Billing for Claims for Screening Glaucoma Services. 2001. (CMS publication 60B, transmittal B-01–46 July 25, 2001). ( http://www.cms.hhs.gov/transmittals/downloads/B0146.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kawas CH, Corrada MM, Brookmeyer R, et al. Visual memory predicts Alzheimer's disease more than a decade before diagnosis. Neurology. 2003;60(7):1089–1093. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000055813.36504.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zonderman AB, Giambra LM, Arenberg D, et al. Changes in immediate visual memory predict cognitive impairment. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 1995;10(2):111–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawas CH, Corrada M, Metter EJ, et al. Neuropsychological differences 20 years before death in subjects with and without Alzheimer's pathology [abstract] Neurology. 1994;44(suppl 2):A141. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dentchev T, Milam AH, Lee VM, et al. Amyloid-beta is found in drusen from some age-related macular degeneration retinas, but not in drusen from normal retinas. Mol Vis. 2003;9:184–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scinto LF, Frosch M, Wu CK, et al. Selective cell loss in Edinger-Westphal in asymptomatic elders and Alzheimer's patients. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22(5):729–736. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00235-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guo L, Salt TE, Luong V, et al. Targeting amyloid-beta in glaucoma treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(33):13444–13449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703707104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fagerström R. Correlations of memory and learning with vision in aged patients before and after a cataract operation. Psychol Rep. 1992;71(3 pt 1):675–686. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1992.71.3.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamura H, Tsukamoto H, Mukai S, et al. Improvement in cognitive impairment after cataract surgery in elderly patients. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30(3):598–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hall TA, McGwin G, Jr, Owsley C. Effect of cataract surgery on cognitive function in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2140–2144. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verghese J, Lipton RB, Katz MJ, et al. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2508–2516. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Tang Y, et al. The effect of social networks on the relation between Alzheimer's disease pathology and level of cognitive function in old people: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(5):406–412. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70417-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gillette Guyonnet S, Abellan van Kan G, Andrieu S, et al. Prevention of progression to dementia in the elderly: rationale and proposal for a health-promoting memory consultation (an IANA Task Force) J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12(8):520–529. doi: 10.1007/BF02983204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]