Abstract

Purpose: Although x-ray projection mammography has been very effective in early detection of breast cancer, its utility is reduced in the detection of small lesions that are occult or in dense breasts. One drawback is that the inherent superposition of parenchymal structures makes visualization of small lesions difficult. Breast computed tomography using flat-panel detectors has been developed to address this limitation by producing three-dimensional data while at the same time providing more comfort to the patients by eliminating breast compression. Flat panels are charge integrating detectors and therefore lack energy resolution capability. Recent advances in solid state semiconductor x-ray detector materials and associated electronics allow the investigation of x-ray imaging systems that use a photon counting and energy discriminating detector, which is the subject of this article.

Methods: A small field-of-view computed tomography (CT) system that uses CdZnTe (CZT) photon counting detector was compared to one that uses a flat-panel detector for different imaging tasks in breast imaging. The benefits afforded by the CZT detector in the energy weighting modes were investigated. Two types of energy weighting methods were studied: Projection based and image based. Simulation and phantom studies were performed with a 2.5 cm polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) cylinder filled with iodine and calcium contrast objects. Simulation was also performed on a 10 cm breast specimen.

Results: The contrast-to-noise ratio improvements as compared to flat-panel detectors were 1.30 and 1.28 (projection based) and 1.35 and 1.25 (image based) for iodine over PMMA and hydroxylapatite over PMMA, respectively. Corresponding simulation values were 1.81 and 1.48 (projection based) and 1.85 and 1.48 (image based). Dose reductions using the CZT detector were 52.05% and 49.45% for iodine and hydroxyapatite imaging, respectively. Image-based weighting was also found to have the least beam hardening effect.

Conclusions: The results showed that a CT system using an energy resolving detector reduces the dose to the patient while maintaining image quality for various breast imaging tasks.

Keywords: Breast imaging, radiation dose, CT, photon counting detector

INTRODUCTION

Breast computed tomography (CT) and photon counting detectors with energy resolution are currently active areas of research for the enhancement of lesion detection.1, 2, 3, 4, 5 The combination of the two, namely, a breast CT system based on a photon counting detector, such as the semiconductor CdZnTe (CZT), would offer distinct advantages. Breast CT was developed to address limitations of mammography such as the reduced sensitivity in women with dense breasts and the inherent superposition of parenchymal structures in projection imaging.6, 7 It was shown that mass detection significantly improved with breast CT as compared to mammography.1 Current breast CT systems use cone-beam geometry with flat-panel detectors. Replacing the charge integrating detector with a CZT photon counting detector allows further improvements in lesion detection by exploiting the energy resolving property. In this study, CT image quality was compared between systems using the two detectors under similar scanning geometry and specifications.

There are three main advantages that a photon counting detector has over a charge integrating detector. First, electronic noise produced by the system can be eliminated. Photon interactions within the CZT crystal produce a voltage that is proportional to the photon’s energy. Comparators examine the voltage to separate the photons into different energy ranges. Setting a voltage threshold just above the noise floor of the detector can effectively eliminate electronic noise. Second, the energy resolving property of the detector provides the capability of varying the contribution of photons to the overall signal. The process of optimally utilizing the photons based on their energy is called energy weighting. The charge integrating detectors’ weighting function is proportional to the energy of the photons, which has been shown to be suboptimal8—lower energy photons usually produce more contrast, but are weighted less. By knowing their energy, photons can be weighted differently to produce images of optimal contrast-to-noise ratio.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Third, since the detected x-ray spectrum is divided into different energy ranges, it can be used to apply multispectral imaging methods such as dual-energy subtraction imaging18, 19, 20, 21 and material decomposition techniques.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 For dual-energy subtraction methods, the spectrum is divided into two ranges where the high and the low energy images (in log signal forms) are linearly combined in such a way that the contrast from a certain material is eliminated—revealing the remaining material. The material decomposition techniques exploit the information in different energy ranges to identify tissue types—effectively providing a spectroscopic imaging technique. All of these imaging techniques have common goals, the enhancement of an image’s diagnostic capability or the ability to make quantitative measurements. This paper focuses on the energy weighting methods and their benefits.

Photon counting detectors based on Si strips,28 Xe gas avalanche, microchannel plates,29, 30, 31 and semiconductors such as CdTe and CdZnTe32, 33, 34 have been developed. These detectors have their limitations—Si is limited by low absorption efficiency, Xe-based detectors perform poorly with photons of higher energies, MCP does not have energy resolution, and CZT is limited by a low count rate. CZT is currently the most advanced of these detectors and has many attractive properties for medical x-ray imaging. These properties include direct conversion of photon energy into charge carriers, capability for high energy and spatial resolution, high density for great radiation stopping power, small volume, and stable performance at room temperature operation.

Previous studies have shown the feasibility of CZT for breast tomography imaging applications.5, 17 The count rate limitation of these detectors is mitigated by the low x-ray flux requirement in breast CT imaging. The CNR improvements of CZT in the energy weighting mode as compared to charge integration mode can be as much as 63% depending on the imaging task. These studies, however, only compared different mode of operations (energy weighting vs. photon counting vs. charge integrating) of one type of detector. Since CZT is an emerging technology and progress is being made to improve aspects such as the purity of the semiconductor crystals,35 the speed of the application specific integrated circuits (ASICs) electronics and bonding methods to the crystals,36 it is important to evaluate its performance in comparison to established technology such as flat-panel detectors. The current study directly compared a prototype CT system that uses a CZT array to a flat-panel detector using a CT phantom for various breast imaging tasks. Thus, results from three types of detectors are reported—CZT photon counting, CZT energy weighting, and flat-panel charge integrating. Energy weighting was implemented in both the projection domain and the image domain. The results are reported with the expectation that advances in CZT technology will provide for further improvements.

METHODS

The contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) of different imaging tasks was compared between the two types of detectors. Both simulation and phantom studies were performed. A phantom was constructed with contrast elements typically found in the breast. Images acquired with the CZT detector were preprocessed in three different modes: Photon counting, projection-based, and image-based weighting.

Simulations

The computed tomography process was simulated to compare an ideal charge integrating to an ideal photon counting detector. The framework of the simulations consisted of three parts—phantom creation, forward projection, and backward projection. For each digital phantom a single slice was used to create linear attenuation coefficient (μ) images as a function of energy in steps of 1 keV. The μ of each material was computed from the linear combinations of the individual μ of its compositions. These values were obtained from previously published results.37, 38 Sinograms for each keV were generated by forward projecting each angular increment using the Beer–Lambert law. An 80 kVp tungsten spectrum was modeled (see Sec. 2F) and used for all simulations. The detectors were assumed to be ideal, with 100% photon absorption, where only noise due to quantum statistics was present. Comparison of the two detectors in the ideal case reveals the benefits afforded by the basic properties (photon counting and energy resolving) of the CZT. The charge integrating data consisted of the sum of the projection images weighted by their corresponding energy. For the photon counting data, the projections were divided into different energy ranges and weighted as described in the following sections. Then filtered backprojection was performed to obtain the reconstructed slices. The geometry and image acquisition parameters were the same as the experiments.

Two simulations were performed: One with a 10 cm diameter breast phantom and one with a 2.5 cm diameter polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) cylinder. In making the breast phantom, a postmortem breast specimen was scanned with a cone-beam CT system. A fuzzy C means algorithm39 segmented the image into mammary gland and adipose tissue. One slice from the volumetric data was chosen as the phantom image. Embedded in the glandular tissue were 0.5 cm iodine (8 mg∕ml) and calcium (hydroxyl apatite, 300 mg∕ml) contrast elements. In another simulation, a 2.5 cm PMMA phantom was constructed and the same iodine and calcium contrast elements were inserted.

Cone-beam CT system

A cone-beam CT system was constructed to investigate breast CT imaging with flat-panel detector. The system consisted of a tungsten target x-ray tube (Dynamax 78E) coupled to a Phillips Optimus M200 x-ray generator, and a CsI indirect flat-panel detector (PaxScan 4030CB, Varian Medical Inc., Palo Alto, CA) mounted on an optical bench. A high precision motor (Kollmorgen Goldline DDR D062M, Danaher Motion, Wood Dale, IL) provided the rotational mechanism and also served as the platform in which the object is placed. The flat-panel detector was operated at 30 frames per second and the motor was rotated at 1.5 rpm. A total of 1300 frames were acquired for each scan with an angular increment of 0.3°. A TTL-logic signal from the flat panel controlled the timing of the x-ray pulse. The synching of this signal and the x-ray pulse was implemented by a field programmable gate array (FPGA) and associated circuits. The detector had an intrinsic pixel size of 194 μm, but for the purpose of comparison with the CZT detector a 4×4 binning was used, effectively increasing the pixel size to 776 μm. The source-to-detector distance (SID) and the source-to-object distance (SOD) were 1.5 and 1 m, respectively. The flat-panel detector had a dimension of 40×30 cm2. To eliminate the effect of scatter in our comparison, fore and aft collimators were constructed. The collimators were made of lead sheets of 3 mm in thickness. The slit widths of the fore and aft collimators were 0.3 and 0.8 mm, respectively. Images were acquired and saved onto a workstation by proprietary software (VARIAN VIVA). Subsequently, the raw data were preprocessed with an open source image processing software package.40

Small FOV CZT CT system

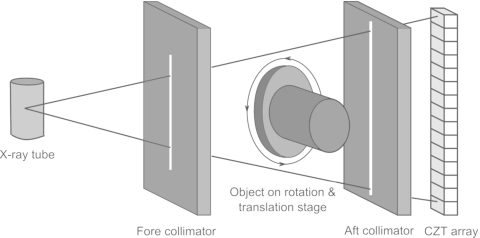

The photon counting CZT CT system was mounted on the same platform as described above with the CZT (eV2500, eV Products, Saxonburg, PA) detector placed just in front of the flat-panel detector. The detector was composed of a linear row of 4 CZT crystals of 12.8 mm in length, 3 mm in width, and 3 mm in thickness. Each crystal was divided into 16 pixels, giving a total of 64 pixels with each pixel having an effective size of 0.8 mm. As photons strike the detector they generate electron and hole pairs that propagate in the opposite directions in accordant with the voltage bias. These electrical charges create a current which is amplified and collected by downstream integrated circuits. The system has five comparators that categorize the photons into their respective energy bins. Each compares the voltage generated by an incoming photon to a user selectable threshold voltage. Corresponding counterincrements by one if the voltage is greater than the threshold. The total count in each energy bin is obtained by finding the count difference in two consecutive bins. A brass collimator shaped the entrance beam to the detector, collimating the height of each pixel of 0.8 mm. This setup was convenient because it allowed for the flat-panel detector to aid in the alignment of the CZT detector. Figure 1 shows a schematic of the CZT setup. The CZT detector communicated with a workstation through a USB port. The signal integration time was 50 ms, yielding an effective frame rate of 20 frames per second. The energy resolving capability of the detector sorted the photons into five user definable energy ranges. Preliminary tests showed that the optimal lowest energy threshold to eliminate electronic noise was 22 keV. Thus, all images were acquired with this setting. With the detector positioned in front of the flat panel, the SID for the CZT system became 1.4 m, whereas the SOD remained the same at 1 m. The lead collimator configuration was the same as the cone-beam CT system. CZT data were acquired with the fluoroscopic mode because of the low tube output required by the photon counting detector.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the CZT CT setup.

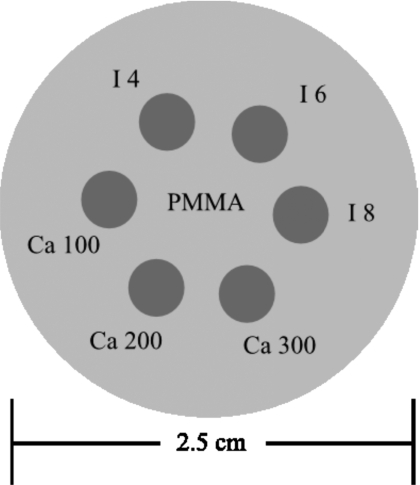

CT phantom

A phantom was constructed from a PMMA cylinder of 2.5 cm in diameter (Fig. 2). The PMMA cylinder was machined with six wells of 0.5 cm in diameter. Embedded in the wells were contrast objects composed of hydroxyapatite (HA, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO) and iodine contrast material (Omnipaque 300, Amersham Health, U.K.). Three concentrations of HA (100, 200, and 300 mg∕ml) and three concentrations of iodine (4, 6, and 8 mg∕ml) were used. Images were generated for the charge integrating (flat panel), photon counting (CZT), and energy weighting (CZT) detectors. The CNRs were measured with the contrast as the difference in CT numbers between the contrast object and the PMMA background, and the noise was measured by averaging the standard deviations of five regions of interest in the background (PMMA) of the image. Images were acquired at 0.37, 0.44, 0.55, 0.72, 1.09, and 2.18 mGy air kerma. The CNRs were plotted versus air kerma and were compared between different types of detectors. The CNR improvements for the photon counting and energy weighting detectors with respect to the flat-panel detector were calculated.

Figure 2.

Schematic of the 2.5 cm cylindrical PMMA phantom. Embedded in the center are different concentrations of iodine and calcium.

Flat-field corrections

All data acquired with the CZT detector were corrected for detector nonuniformity. A flat-field correction technique was implemented to compensate for the nonuniformity across pixels. Immediately before the phantom was scanned, three slabs of PMMA were used to acquire flat-field images at different levels of attenuations. The slabs had thicknesses of 5.3, 11.1, and 13.1 mm. Together with the open field image and different combinations of slabs, eight flat-field images (0, 5.3, 11.1, 13.1, 16.4, 18.4, 24.2, and 29.5 mm) were acquired. These thicknesses spanned the range of thicknesses of the 2.5 cm cylindrical phantom. For each flat-field image the gain (Gi) associated with each pixel is calculated by

| (1) |

where Pi is raw pixel readout of the ith pixel, N is the number of pixels, and Gi is the gain. The gains were linearly fitted in a piecewise manner with pixel values for the eight flat-field images of each pixel. Thus, 64 pixels would have 64 gain fits. During subsequent scan of the phantom, the corrected pixel values were calculated by

| (2) |

where Pri is the raw count of pixel i and Pci is the corrected count. The gain for each pixel was obtained from the linear fits described above.

Spectral model

The x-ray transport process was simulated to calculate the μ of different materials as seen by a particular detector type. X-ray spectra were computer generated for the simulation.41 The spectral model was incorporated into a JAVA program that could output a desired spectrum according to parameters such as tube target material, peak voltage, ripple fraction, and beam filtration. The spectral model was matched to the output of the tube in our laboratory. The output of the tube was measured at 1 m with a 60 cc ionization chamber (20X6–60, Radcal, Monrovia, CA). The tube voltage was varied from 40 to 110 kV in increments of 5 kV. Exposure was measured for an x-ray beam of 200 mA s and converted to air kerma. The tube had a tungsten target, an inherent and added aluminum filtrations of 0.6 and 2 mm, respectively. To match the tube output to the spectral model, spectra were generated with varying filtrations of aluminum thicknesses and compared to the experimental measurement with respect to air kerma at 1 m. Air kerma was calculated according to

| (3) |

where X is the air kerma in gray (J∕kg), Φ is the photon fluence in photons∕m2, (μ(E)∕ρ)en is the mass energy absorption coefficient of air in m2∕kg, and E is the energy of the photons in keV. The factor 1.602×10−16 has unit of J∕keV. After the parameters for the spectral model were optimized, it was used for all subsequent calculations.

Projection-based energy weighting

Optimal energy weighting of the CZT data was calculated for the projection images. The data from the five energy bins were linearly combined with the weighting factors before CT reconstruction. Taking into account the contrast dependence on the μ, each energy bin of the CZT detector is weighted according to the transmission properties of the object and the background.11 The weights are optimized so that the energy bins that contribute more to image quality are weighted more. In other words, the weighting factor is proportional to the contrast-to-noise ratio in the projection image. The weighting factor for each energy bin is calculated using the spectral model and the object properties and was shown to be optimized by11

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where w(b) is the weighting factor for the energy bin b, N’s are the transmitted x-ray intensities, μ’s are the effective linear attenuation coefficient for each energy bin, t’s are the material thicknesses, and the subscripts back and obj refer to the background and object materials, respectively. Nobj is calculated with the object displacing part of the background volume. The effective μ’s depend on the transmitted spectrum and are calculated as follows:

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

where NT0 and NT are the unattenuated and attenuated intensities for photons in a particular energy bin. Emin and Emax are the lowest and highest energies of the bin. These values were calculated using the spectral model described above.

Image-based energy weighting

The energy weighting method can be applied in the projection domain, as described above, or the reconstructed image domain. For the latter, CT data from the five energy bins were reconstructed separately, and then linearly combined according to the computed weights. Here, the weighting factor depends on the image quality of the reconstructed energy-bin images. The weighting factors were computed from theoretical CNR’s, which were determined from the spectral model and the properties of the contrast and background elements.42 The optimal weighting factor of each energy bin is proportional to the CNR of that bin, which was derived previously42 and summarized here. The CNR of an image is given by

| (10) |

where C is the absolute contrast between the object and background and σ is the standard deviation in the background. The contrast is calculated by taking the absolute value of the difference between the object intensity and background intensity. The CNR (CNRtot) of the combined image is given by the weighted contrast divided by the weighted noise,

| (11) |

where wb the weighting factor for the energy bin b and m is the total number of energy bins. The objective is to find wb, such that CNRtot is maximized. Taking the derivative of Eq. 10 with respect to weight at the nth energy bin wn, we obtain

| (12) |

If the weights are chosen so that they are proportional to the contrast to noise variance ratio , Eq. 12 becomes

| (13) |

Equation 13 indicates that the CNR of the combined image is maximized when the weight is proportional to the contrast-to-noise variance ratio of the individual energy bin images. In these equations contrast is determined from the differences in the effective μ of the object and background,

| (14) |

where μ’s are the effective linear attenuation coefficients of the object and background. The effective μ’s are computed according to Eq. 7. Also, depends on the number of detected photons (Nb,i) and the number of projections (k) sampled with CT scanning,

| (15) |

The weights were computed before image acquisition and were normalized to a sum of 1 before being applied to reconstructed energy bin images.

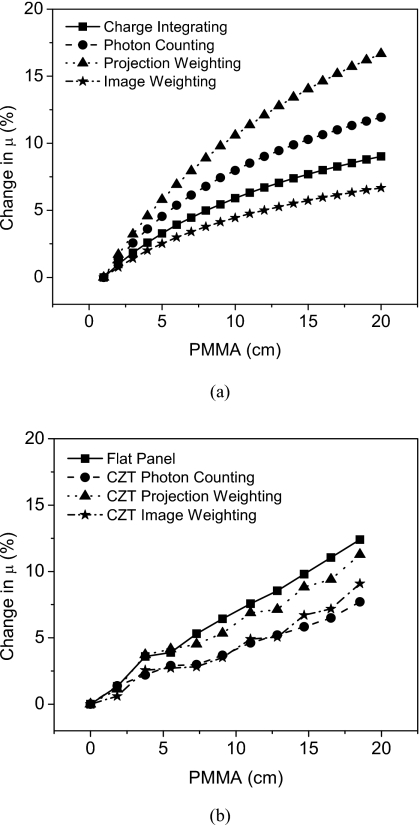

Quantification of beam hardening

The beam hardening effect was quantified for the different types of detectors. Since the extent of beam hardening depends on the quality of the spectrum, different weighting methods are expected to produce varying levels of beam hardening. In a previous simulation study,42 it was found that projection-based energy weighting increased the beam hardening effect by 7.6% while image-based weighting decreased the effect by 4.6%. Here, the effect is measured experimentally to quantify the benefit of using the CZT detector. The extent of beam hardening was calculated by measuring the μ of a PMMA slab of 1 cm thickness after the beam has passed through varying amounts of PMMA (0, 1.84, 3.76, 5.52, 7.29, 9.08, 11, 12.85, 14.69, 16.54, and 18.53 cm). Both a simulation and an experimental study were performed.

RESULTS

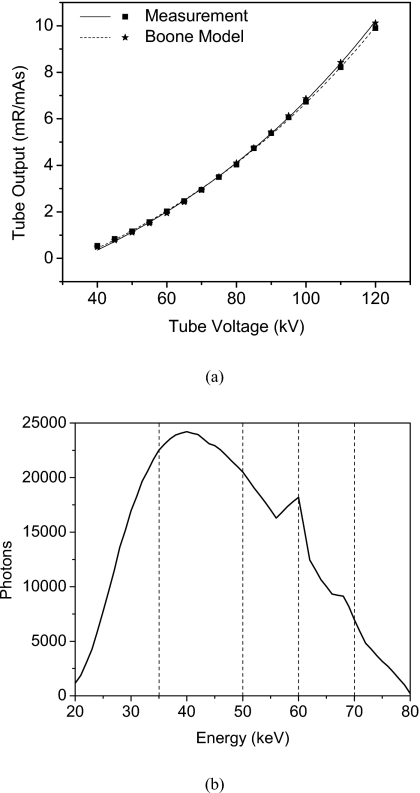

The tube output measurements and the simulated spectral model are shown in Fig. 3. The model that best matched the tube output was a tungsten spectrum with 0% ripple, filtered by 2.7 mm of aluminum. The average error in exposure output between measurement and model was 2.86%. Also shown is the 80 kVp spectrum that was used in all the simulations.

Figure 3.

Tube output measurements and the corresponding spectral model (a). The total aluminum filtrations were 2.6 and 2.7 mm for the tube and the model, respectively. The 80 kV spectrum with divisions of energy bin is also shown (b).

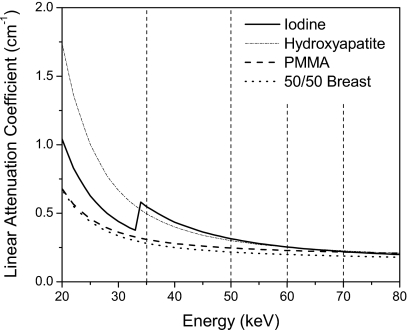

Figure 4 shows the μ of iodine, HA, PMMA, and breast tissue composing of 50% glandular and 50% adipose tissue. The μ of breast tissue is also shown to indicate its similarity to PMMA. The thresholds (Table 1) that define the energy bins of the CZT detector are indicated. These figures depict the functional dependence of the μ of different materials on photon energy. The differences in μ curves produce the contrast between two materials on CT images. The μ separation between two materials is generally higher for photons of lower energies. An exception is in the iodine μ curve, where there is a k-edge at 33.2 keV.

Figure 4.

The linear attenuation coefficient of iodine, hydroxyapatite, PMMA, and 50∕50 breast tissue. Also shown are the five energy bins used for CZT imaging.

Table 1.

Energy range for bins 1–5.

| Energy bin | Range (keV) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 22–35 |

| 2 | 35–50 |

| 3 | 50–60 |

| 4 | 60–70 |

| 5 | 70–80 |

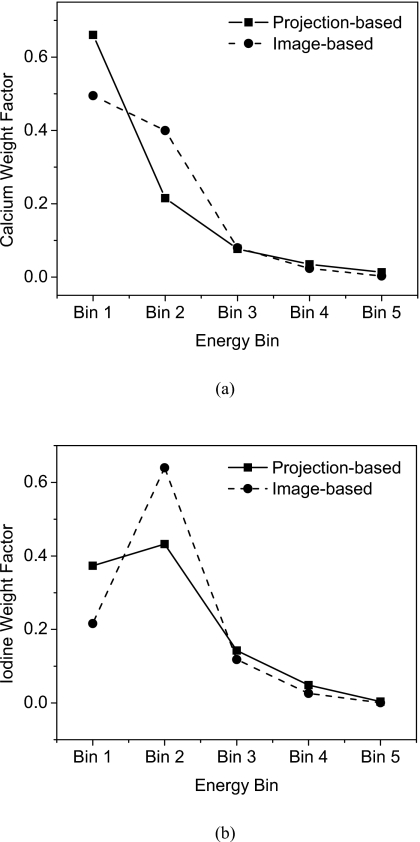

These μ and the spectral model were used to calculate the weighting factors for HA [Fig. 5a] and iodine [Fig. 5b]. Both projection-based and image-based weighting factors are shown. There are differences in the weighting factors of the two methods, but the trend is similar. The lower energy bins were generally weighted more than the higher ones, with the exception of iodine∕PMMA where the second bin has the largest weighting factor.

Figure 5.

Weight factors for the five energy bins are shown for HA (a) and Iodine (b). Projection-based and image-based values indicate their similarity in trend.

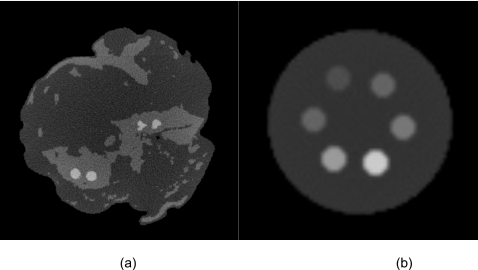

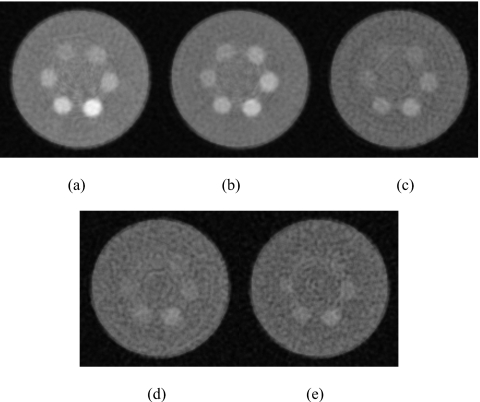

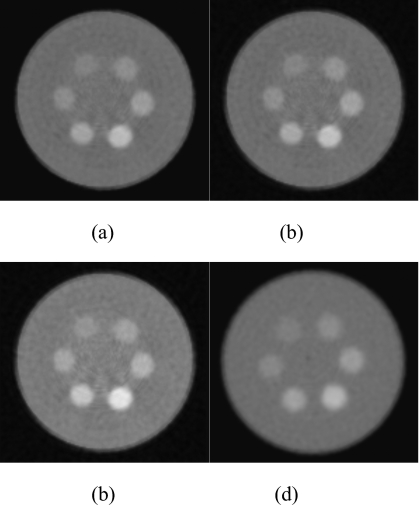

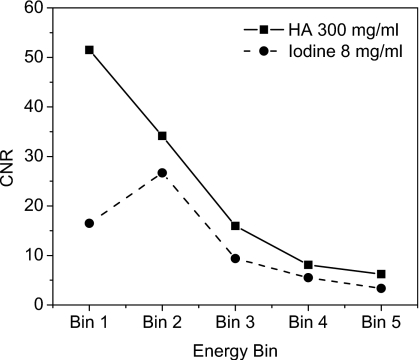

Figure 6 shows the reconstructed slices of the charge integrating detector for simulations of the 10 cm postmortem specimen and the 2.5 cm PMMA phantom. The HA and iodine contrast elements are distinguishable from the background but not from each other. Images of the phantom scanned with the CZT system are shown in Fig. 7. The contrast was computed by subtracting the mean voxel values of a region of interest (ROI) inside the object from the background. The noise was computed from the average of the standard deviation of four ROIs in the background. The figures indicate that, as expected, the image quality progressively worsens from energy bin 1 to bin 5. Figure 8 shows images of the phantom reconstructed using all energy bins that were scanned with the CZT photon counting [Fig. 8a] CZT projection-based weighting with respect to HA∕PMMA [Fig. 8b], CZT image-based weighting with respect to HA∕PMMA [Fig. 8c], and the charge integrating flat-panel detector [Fig. 8d]. The CNR for different energy bins was plotted for HA (300 mg∕ml) and iodine (8 mg∕ml) in Fig. 9. The CNR progressively decreased from bins 1 to 5 for HA. But for iodine, the highest CNR was at bin 2 where iodine’s k-edge resides.

Figure 6.

The reconstructed slice for the simulation experiments of the 10 cm breast (a) and the 2 cm PMMA cylinder (b). Iodine and HA contrast elements are visible. Window=400, level=400.

Figure 7.

Reconstructed slice of the phantom for bin 1 (a), bin 2 (b), bin 3 (c), bin 4 (d), and bin 5 (e). Window=1000, level=400.

Figure 8.

Reconstructed slice of the phantom for different detector types: Photon counting (a), projection-based weighting HA (b), image-based weighting HA (c), and charge integrating (d). Window=1000, level=400.

Figure 9.

Contrast-to-noise ratio vs energy bin for HA (300 mg∕ml) and iodine (8 mg∕ml).

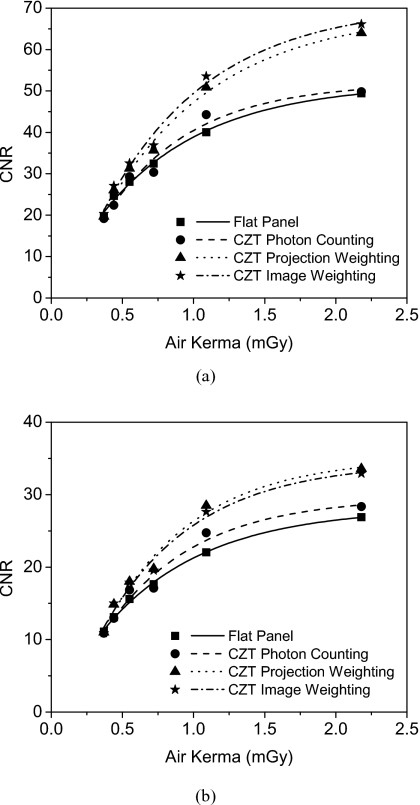

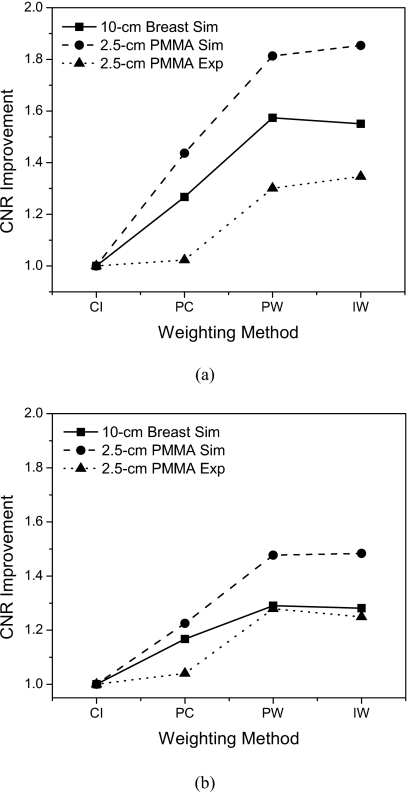

Figure 10 depicts the CNR as a function of air kerma for the 2.5 cm PMMA phantom. The fits to the curve were found to be exponential in shape, which is due to the exponential relationship of CT noise and dose.43 The CNR of the optimally energy weighted detectors were found to be higher than for photon counting and charge integrating detectors. By taking the CNR of the charge integrating detectors as the reference the CNR improvements were calculated and are shown in Fig. 11. Table 2 summarizes these results where the CNR improvements of the energy weighted detectors were found to be comparable. For HA, the measured CNR improvements were 1.02, 1.30, and 1.35 for photon counting, projection-based weighting, and image-based weighting, respectively. For iodine, the CNR improvements were 1.04, 1.28, and 1.25.

Figure 10.

CNR as a function of air kerma of the experimental 2.5 cm PMMA cylinder for 300 mg∕ml HA (a) and 8 mg∕ml iodine (b).

Figure 11.

CNR improvement as a function of the energy weighting methods for HA (a) and Iodine (b). Values from both simulations and experiments are shown. CI=charge integrating, PC=photon counting, PW=projection-based weighting, IW=image-based weighting.

Table 2.

Contrast-to-noise improvements for images acquired at 2.18 mGy.

| Hydroxyapatite | Iodine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation 10 cm breast | Simulation 2.5 cm PMMA | Measurement 2.5 cm PMMA | Simulation 10 cm breast | Simulation 2.5 cm PMMA | Measurement 2.5 cm PMMA | |

| Photon counting | 1.27 | 1.44 | 1.02 | 1.17 | 1.23 | 1.04 |

| Projection based | 1.57 | 1.81 | 1.3 | 1.29 | 1.48 | 1.28 |

| Image based | 1.55 | 1.85 | 1.35 | 1.28 | 1.48 | 1.25 |

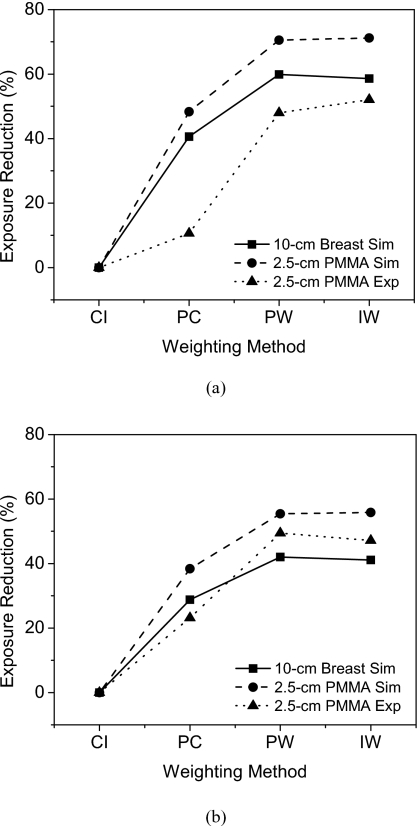

Setting the CNR of a flat-panel image acquired at 2.18 mGy as the reference, the expected dose level and percentage reduction in dose were calculated for the other weighting methods. Thus, the expected dose reduction was calculated by setting the CNR to be the same as that of the flat-panel image acquired at 2.18 mGy. Figure 12 shows the dose reductions for HA (300 mg∕ml) and iodine (8 mg∕ml). For HA, the measured dose reductions were 10.60%, 47.96%, and 52.05% for photon counting, projection-based weighting, and image-based weighting, respectively. For iodine, they were 23.18%, 49.45%, and 47.16%. The results are also summarized in Table 3.

Figure 12.

Exposure reduction, compared to CNR value of the charge integrating∕flat-panel detector at 2.18 mGy, as a function of the energy weighting methods for HA (a) and iodine (b). Values from both simulations and experiments are shown. CI=charge integrating, PC=photon counting, PW=projection-based weighting, IW=image-based weighting.

Table 3.

Exposure reductions (in percentage) when setting the CNR of the flat-panel image acquired at 2.18 mGy as the reference.

| Hydroxyappatite | Iodine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation 10 cm breast | Simulation 2.5 cm PMMA | Measurement 2.5 cm PMMA | Simulation 10 cm breast | Simulation 2.5 cm PMMA | Measurement 2.5 cm PMMA | |

| Photon counting | 40.60 | 48.34 | 10.60 | 28.80 | 38.38 | 23.18 |

| Projection based | 59.90 | 70.55 | 47.96 | 42.02 | 55.45 | 49.45 |

| Image based | 58.63 | 71.18 | 52.05 | 41.12 | 55.85 | 47.16 |

Quantification of the beam hardening effect is shown in Fig. 13. For simulations, the change in μ for a 1 cm of PMMA after the beam had penetrated 18 cm of PMMA were 8.53%, 11.32%, 15.71%, and 6.33% for the charge integrating, photon counting, and projection and image based weighting, respectively. For measurements, the change in μ for a 1 cm of PMMA after the beam had penetrated 18.5 cm of PMMA were 12.39%, 7.71%, 11.27%, and 9.08% for the charge integrating, photon counting, and projection and image based weighting, respectively.

Figure 13.

Beam hardening quantification shows amount of change in μ for simulations (a) and measurements (b).

DISCUSSION

The objective of the current study was to directly compare the performance of a flat-panel based to CZT-based CT system by using a breast phantom with calcium and iodine contrast elements. These contrast elements were chosen because they are relevant in breast imaging with respect to microcalcification and contrast enhanced breast imaging. A previous report compared the CNR of these contrast elements between different modes of the CZT detector. It was found that the CNR improvements of the projection-based weighting mode were 1.40 and 1.63 for calcium and iodine contrasts.5 These values were obtained by comparing optimal energy weighting to the charge integrating (or proportional) weighting of the same CZT data. The CNR improvements for the respective contrast elements in our experiment were 1.30 and 1.28. These improvement values take into account other properties of the detectors. For example, the absorption efficiency of the cesium iodide in the flat panel and the CZT crystal is not the same. Also, flat panel is currently a more advanced technology and therefore more reliable in terms of its response to incident radiation. As such, these differences may contribute to the overall CNR improvement and dose reduction in the CZT system. But the comparison is justified because these system properties will inevitably need to be considered in evaluating an imaging modality. In our simulation of the same imaging setup, the CNR improvements were 1.85 and 1.48. One factor that might contribute to the lower improvement values is the necessity to set the lowest threshold to be 22 keV due to detector limitations. Counting photons with energy lower than 22 keV was hindered by inclusion of electronic noise. The exclusion of these low energy photons resulted in a lowered contrast value, whereas the flat panel integrated all photons. This effect is probably small because the number of photons below 22 keV is only a small percentage (∼1%) of the total spectrum. Another factor could be due to the imperfect compensation for the field nonuniformity of the CZT detector.35 Flat-panel detectors are currently a more matured technology than CZT detectors. Issues regarding material properties and detector constructions are currently under active investigations for CZT detectors. Nonuniformity problems do not show up in the CNR improvements when comparing different methods of energy weighting with the same CZT data because the nonuniformity would propagate to images of all weighting methods. Despite these considerations, our results indicate that using a CZT detector has a potential of ∼50% decrease in dose for the imaging parameters described. The simulated dose reduction for the same parameters was ∼70%, further highlighting the detector imperfections. Simulation of the 10 cm breast specimen showed comparable dose reduction in ∼60% and ∼40% for HA and iodine, respectively. These values correspond to an air kerma level of 2.18 mGy. Further examinations are required to characterize the detector’s performance at different dose levels.

Two types of optimal energy weighting methods were investigated in this study. It was found that the CNR improvement did not differ greatly between projection-based (1.30 and 1.28) and image-based weighting (1.35 and 1.25). This finding agrees with simulation from a recent investigation42 as well as with our simulation results. Although the difference is small, any improvement will benefit the image quality. The image-based CNR for HA was higher than for projection based, whereas for iodine the opposite occurred. This result can be due to the different ways the two methods are optimized and that the contrast and noise are transferred in a complex way from projection data to image data. This aspect needs further investigation.

The decrease in the beam hardening effect makes the image-based weighting method attractive. This effect was quantified by measuring the change in μ due to the fact that the 2.5 cm phantom was too small to see the resulting cupping artifact. In both simulation and measurement the image weighting method showed less beam hardening than the charge integrating and projection weighting. According to simulations, the projection weighting method has the most beam hardening due to the preferential weighting of lower energy photons. Image-based weighting would perform the best since the μ would depend less on the thickness of the object measured.42 Our experimental results deviated somewhat from simulations with the flat panel and photon counting detectors exhibiting the most and least beam hardening, respectively. Detector imperfections could have interfered with our μ measurements. For example, the nonideal and differential energy resolution properties of the pixels would make the weighting function inaccurate and affect the μ measurement. Nevertheless, the reduction in beam hardening with image-based weighting is clear.

The envisioned system is a multislit scanning breast CT system, with the required count rate in the open field for the CZT detectors as 1 500 000 counts∕s∕mm2. Our detector’s average count rate for the spectrum used was approximately 312 500 counts∕s∕mm2. This flux level was chosen so that all pixels operate well within their linear response range. A linearity test was performed and the maximum count rate in which all pixels responded linearly was approximately 600 000 counts∕s∕mm2. The count rate depends both on the quality of the CZT crystal and the performance of associated electronics.36 One of the factors that contribute to the limitation is the poor hole transport property of the CZT crystals. The electrons and holes created as x-ray photons interact with the detectors differ greatly in their mobility and lifetime. The typical mobility and lifetime for electrons are 1350 cm2∕V s and 3–7 ns and for holes 120 cm2∕V s and 50–300 ns, respectively.44 Due to the low mobility and lifetime of holes they are trapped and the charge is lost, resulting in detection at a lower energy than the actual value. Current CZT crystals are grown by a method called the high pressure Bridgman (HPB) technique that produces polycrystals which can suffer from a nonuniform distribution of charge transport properties.36 Thus, there is usually some variation in the charge transport properties between different detectors. The other aspect that influences the final count rate of the detector is the readout electronics’ capability of processing a large number of signals. The highest count rate that has been reported for a CZT detector was 5 M counts∕s∕mm2.36 This system used fast bipolar front end application specific integrated circuits. This count rate would satisfy the requirement for a breast CT system. Although our current detector’s count rate is below the requirement, current technology allows the feasibility of such a system.

As evident from Figs. 78, the CT images contain ring artifacts due to imperfect correction of detector nonuniformity.45 Other sources of artifact are the dead spaces between the CZT crystals. The current system consists of four crystals; therefore, three dead spaces are present. We tested different techniques for flat-field correction. The simplest method is acquiring one flat-field image and using it to correct subsequent images. Another method is a multipoint approach where the flux to the detector was varied and more than one flat-field image was used. Significant ring artifacts were still present after performing these two correction methods. Varying the flux does not take into account the spectral shape of the beam as it passes through the materials. Thus, we used different PMMA thicknesses to vary the flux. Using different PMMA thicknesses mimics the process of attenuation of the object and therefore faithfully approximates the spectral shape of the beam. We found this method of nonuniformity correction to be the best approach. Also, fitting all the gain values to one linear regression did not perform as well as fitting the values in a piecewise manner. Despite the more sophisticated correction technique, ring artifacts were still present in the center of the reconstructed slice.

The chosen x-ray technique of 80 kVp was to match the previously reported cone-beam breast CT studies.46, 1 Dose studies were investigated at this kVp for matching the dose of a breast CT scan to that of a standard two-view mammogram. However, the spectral shape of the beam may affect the CNR of particular contrast objects. In fact, a previous investigation used 110 kV and reported different values of theoretical CNR for the same imaging tasks as the current study.17, 5 The main focus of this study was to compare the new photon counting detector with existing flat-panel detectors that are used in current breast CT systems. The use of an 80 kVp spectrum was sufficient for this purpose. Further studies are needed to determine the optimal x-ray spectrum for maximizing the CNR while limiting the dose.

The positions of the energy bins were chosen with the criterion of spacing them as far apart as possible and to assure that sufficient number of photons will reach the detector for each bin. An ideal energy weighting detector would have a bin size of 1 keV, but practical considerations limit the number of bins and therefore the bin size would be much larger. The detector used for this study has five bins. A study showed that the CNR of blood∕blood iodine weakly depends on the size of the energy bin for a 120 kVp spectrum.12 The CNR improvement was 1.4 at bin size of 10 keV and decreased to 1.35 at 40 keV. This corresponds to 12 and 3 energy bins, respectively. Another simulation, which used energy thresholds of 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120 for a 120 kVp beam, showed that the CNR did not significantly improve when going from 5 bins to 15 bins.17 Using two energy bins, the bin border position was also found to affect the CNR improvement. The maximum and minimum CNR improvements were 1.33 and 1.17, respectively, for a range of positions simulated.12 Thus, optimizing the energy bin size and position can potentially improve the CNR of the energy weighting detector.

In conclusion, our prototype CZT-based CT system performed better than a charge integrating flat-panel system for several imaging tasks in breast imaging. It has the potential to reduce dose by as much as ∼50% by using optimal energy weighting. Simulations of a breast specimen also showed similar dose reduction levels. Experiment with a breast specimen would require a full FOV system, which is a matter of current investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported in part by Grant No. R01 CA136871 awarded by the National Cancer Institute and a fellowship Award No. F31EB009630 from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering or the National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank David Rundle and Richard Smith from eV Microelectronics for their technical support.

References

- Lindfors K. K., Boone J. M., Nelson T. R., Yang K., Kwan A. L., and Miller D. F., “Dedicated breast CT: Initial clinical experience,” Radiology 246(3), 725–733 (2008). 10.1148/radiol.2463070410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick S. J., “Breast CT,” Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 9, 501–526 (2007). 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.9.060906.151924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C. J., Shaw C. C., Chen L. Y., Altunbas M. C., Liu X. M., Han T., Wang T. P., Yang W. T., Whitman G. J., and Tu S. J., “Visibility of microcalcification in cone beam breast CT: Effects of x-ray tube voltage and radiation dose,” Med. Phys. 34(7), 2995–3004 (2007). 10.1118/1.2745921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlomka J. P., Roessl E., Dorscheid R., Dill S., Martens G., Istel T., Baumer C., Herrmann C., Steadman R., Zeitler G., Livne A., and Proksa R., “Experimental feasibility of multi-energy photon-counting K-edge imaging in pre-clinical computed tomography,” Phys. Med. Biol. 53(15), 4031–4047 (2008). 10.1088/0031-9155/53/15/002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikhaliev P. M., “Energy-resolved computed tomography: First experimental results,” Phys. Med. Biol. 53(20), 5595–5613 (2008). 10.1088/0031-9155/53/20/002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann C. A., Kopans D. B., Mccarthy K. A., White G., and Hall D. A., “Mammographic density and physical assessment of the breast,” AJR, Am. J. Roentgenol. 148(3), 525–526 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson V. P., Hendrick R. E., Feig S. A., and Kopans D. B., “Imaging of the radiographically dense breast,” Radiology 188(2), 297–301 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapiovaara M. J. and Wagner R. F., “Snr and Dqe analysis of broad-spectrum x-ray-imaging,” Phys. Med. Biol. 30(6), 519–529 (1985). 10.1088/0031-9155/30/6/002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cahn R. N., Cederstrom B., Danielsson M., Hall A., Lundqvist M., and Nygren D., “Detective quantum efficiency dependence on x-ray energy weighting in mammography,” Med. Phys. 26(12), 2680–2683 (1999). 10.1118/1.598807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner M., Blanquart L., Fischer P., Kruger H., and Wermes N., “Medical X-ray imaging with energy windowing,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 465(1), 229–234 (2001). 10.1016/S0168-9002(01)00395-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giersch N. A. G., “The influence of energy weighting on x-ray imaging quality,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 531, 68–74 (2004). 10.1016/j.nima.2004.05.076 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niederlohner D., Karg J., Giersch J., and Anton G., “The energy weighting technique: Measurements and simulations,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 546(1–2), 37–41 (2005). 10.1016/j.nima.2005.03.037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karg J., Niederlohner D., Giersch J., and Anton G., “Using the Medipix2 detector for energy weighting,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 546(1–2), 306–311 (2005). 10.1016/j.nima.2005.03.033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giersch E., Firsching M., Niederlohner D., and Anton G., “Material reconstruction with spectroscopic pixel x-ray detectors,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 546(1–2), 125–130 (2005). 10.1016/j.nima.2005.03.104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patatoukas G., Gaitanis A., Kalivas N., Liaparinos P., Nikolopoulos D., Konstantinidis A., Kandarakis I., Cavouras D., and Panayiotakis G., “The effect of energy weighting on the SNR under the influence of non-ideal detectors in mammographic applications,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 569(2), 260–263 (2006). 10.1016/j.nima.2006.08.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shikhaliev P. M., “Tilted angle CZT detector for photon counting/energy weighting x-ray and CT imaging,” Phys. Med. Biol. 51(17), 4267–4287 (2006). 10.1088/0031-9155/51/17/010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shikhaliev P. M., “Computed tomography with energy-resolved detection: A feasibility study,” Phys. Med. Biol. 53(5), 1475–1495 (2008). 10.1088/0031-9155/53/5/020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asaga T., Masuzawa C., Yoshida A., and Matsuura H., “Dual-energy subtraction mammography,” J. Digit. Imaging 8(1), 70–73 (1995). 10.1007/BF03168071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliznakova K., Kolitsi Z., and Pallikarakis N., “Dual-energy mammography: Simulation studies,” Phys. Med. Biol. 51(18), 4497–4515 (2006). 10.1088/0031-9155/51/18/004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloi S. Y., Dynamic Dual-Energy X-Ray Techniques for Cardiac Imaging (University of Wisconsin, Madison, 1987). [Google Scholar]

- Xu T., Ducote J. L., Wong J. T., and Molloi S., “Feasibility of real time dual-energy imaging based on a flat panel detector for coronary artery calcium quantification,” Med. Phys. 33(6), 1612–1622 (2006). 10.1118/1.2198942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez R. E. and Macovski A., “Energy-selective reconstructions in X-ray computerized tomography,” Phys. Med. Biol. 21(5), 733–744 (1976). 10.1088/0031-9155/21/5/002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody W. R., Butt G., Hall A., and Macovski A., “A method for selective tissue and bone visualization using dual energy scanned projection radiography,” Med. Phys. 8(3), 353–357 (1981). 10.1118/1.594957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann L. A., Alvarez R. E., Macovski A., Brody W. R., Pelc N. J., Riederer S. J., and Hall A. L., “Generalized image combinations in dual KVP digital radiography,” Med. Phys. 8(5), 659–667 (1981). 10.1118/1.595025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardinal H. N. and Fenster A., “An accurate method for direct dual-energy calibration and decomposition,” Med. Phys. 17(3), 327–341 (1990). 10.1118/1.596512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns P. C., Drost D. J., Yaffe M. J., and Fenster A., “Dual-energy mammography: Initial experimental results,” Med. Phys. 12(3), 297–304 (1985). 10.1118/1.595767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappadath S. C. and Shaw C. C., “Dual-energy digital mammography for calcification imaging: Scatter and nonuniformity corrections,” Med. Phys. 32(11), 3395–3408 (2005). 10.1118/1.2064767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuville E., Cahn R., Cederstrom B., Danielsson M., Hall A., Hasegawa B., Luo L., Lundqvist M., Nygren D., Oltman E., and Walton J., “High resolution X-ray imaging using a silicon strip detector,” IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 45(6), 3059–3063 (1998). 10.1109/23.737664 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shikhaliev P. M. and Molloi S., “X-ray imaging with “edge-on” microchannel plate detector: First experimental results,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 510(3), 401–405 (2003). 10.1016/S0168-9002(03)01946-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shikhaliev P. M., Xu T., and Molloi S., “Evaluation of a photon counting x-ray imaging detector based on microchannel plates for mammography applications,” Proc. SPIE 5368, 726–733 (2004). 10.1117/12.535476 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shikhaliev P. M., Xu T., Le H., and Molloi S., “Scanning-slit photon counting x-ray imaging system using a microchannel plate detector,” Med. Phys. 31(5), 1061–1071 (2004). 10.1118/1.1695651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruska C. B. and O’Connor K. M., “CZT detectors: How important is energy resolution for nuclear breast imaging?,” Phys. Med. 21(1), 72–75 (2006). 10.1016/S1120-1797(06)80029-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moraes D., Kaplon J., and Jarron P., “Solid-state photo-detectors for both CT and PET applications,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 571(1–2), 333–338 (2007). 10.1016/j.nima.2006.10.094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prokesch M. and Szeles C., “Accurate measurement of electrical bulk resistivity and surface leakage of CdZnTe radiation detector crystals,” J. Appl. Phys. 100(1), 014503 (2006). 10.1063/1.2209192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sellin P. J., “Recent advances in compound semiconductor radiation detectors,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 513(1–2), 332–339 (2003). 10.1016/j.nima.2003.08.058 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szeles C., Soldner S. A., Vydrin S., Graves J., and Bale D. S., “Ultra high flux 2-D CdZnTe monolithic detector arrays for x-ray imaging applications,” IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 54(4), 1350–1358 (2007). 10.1109/TNS.2007.902362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell J. H. and Seltzer S. M., “Tables of x-ray mass attenuation coefficient and mass energy absorption coefficients 1 keV to 20 MeV for elements Z=1 to 92 and 48 additional substances of dosimetric interest,” NIST Report No. NISTIR 5632, 1995.

- Boone J. M. and Chavez A. E., “Comparison of x-ray cross sections for diagnostic and therapeutic medical physics,” Med. Phys. 23(12), 1997–2005 (1996). 10.1118/1.597899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. J., Giger M. L., and Bick U., “A fuzzy c-means (FCM)-based approach for computerized segmentation of breast lesions in dynamic contrast-enhanced MR images,” Acad. Radiol. 13(1), 63–72 (2006). 10.1016/j.acra.2005.08.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband W. S., “ImageJ” (U. S. National Institutes of Health, 1997–2005), retrieved http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/, 1997–2005.

- Boone J. M. and Seibert J. A., “An accurate method for computer-generating tungsten anode x-ray spectra from 30 to 140 kV,” Med. Phys. 24(11), 1661–1670 (1997). 10.1118/1.597953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt T. G., “Optimal “image-based” weighting for energy-resolved CT,” Med. Phys. 36(7), 3018–3027 (2009). 10.1118/1.3148535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone J. M., Nelson T. R., Lindfors K. K., and Seibert J. A., “Dedicated breast CT: Radiation dose and image quality evaluation,” Radiology 221(3), 657–667 (2001). 10.1148/radiol.2213010334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato G., Parsons A., Hullinger D., Suzuki M., Takahashi T., Tashiro M., Nakazawa K., Okada Y., Takahashi H., Watanabe S., Barthelmy S., Cummings J., Gehrels N., Krimm H., Markwardt C., Tueller J., Fenimore E., and Palmer D., “Development of a spectral model based on charge transport for the Swift/BAT 32 K CdZnTe detector array,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 541(1–2), 372–384 (2005). 10.1016/j.nima.2005.01.078 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sijbers J. P. and Postnov A., “Reduction of right artefacts in high resolution micro-CT reconstruction,” Phys. Med. Biol. 49, N247–N253 (2004). 10.1088/0031-9155/49/14/N06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone J. M., Kwan A. L. C., Seibert J. A., Shah N., Lindfors K. K., and Nelson T. R., “Technique factors and their relationship to radiation dose in pendant geometry breast CT,” Med. Phys. 32(12), 3767–3776 (2005). 10.1118/1.2128126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]