Abstract

Cerebellar Purkinje neurons receive two major excitatory inputs, the climbing fibers (CFs) and parallel fibers (PFs). Simultaneous, repeated activation of CFs and PFs results in the long-term depression (LTD) of the amplitude of PF-evoked synaptic currents. To induce LTD, activation of CFs may be substituted with depolarization of the Purkinje neuron to turn on voltage-activated calcium channels and increase the intracellular calcium concentration. The role of PFs in the induction of LTD, however, is less clear. PFs activate glutamate metabotropic receptors that increase phosphoinositide turnover and elevate cytosolic inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3). It has been proposed that calcium release from intracellular stores via InsP3 receptors may be important in the induction of LTD. We studied the role of InsP3 in the induction of LTD by photolytic release of InsP3 from its biologically inactive “caged” precursor in voltage-clamped Purkinje neurons in acutely prepared cerebellar slices. We find that InsP3-evoked calcium release is as effective in LTD induction as activation of PFs. InsP3-induced LTD was prevented by calcium chelator 1,2-bis(2-amino phenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid. LTD produced either by repeated activation of PFs combined with depolarization (PF+ΔV), or by InsP3 combined with depolarization (InsP3+ΔV) saturated at ≈50%. Maximal LTD induced by PF+ΔV could not be further increased by InsP3+ΔV and vice versa, which suggests that both protocols for induction of LTD share a common path. In addition to inducing LTD, photo-release of InsP3+ΔV resulted in the rebound potentiation of inhibitory synaptic currents. In the presence of heparin, an InsP3 receptor antagonist, repeated activation of PF+ΔV failed to induce LTD, suggesting that InsP3 receptors play an important role in LTD induction under physiological conditions.

The cerebellum plays a central role in the regulation and learning of motor tasks (1), probably by modifying the strength of synaptic inputs to its principal neurons, the Purkinje cells (1–3), which receive excitatory inputs from both climbing fibers (CFs) and parallel fibers (PFs). Repeated concurrent activation of CFs and PFs results in long-term depression (LTD) of the response to PF stimulation (4). Calcium ions play a vital role in LTD because limiting changes in the intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) by addition of calcium chelators to the cytosol inhibits induction of LTD (5). CF activation can be replaced by depolarization of the Purkinje cell, which causes calcium influx via voltage-activated calcium channels (6). The role of PFs in LTD is less clear. Activation of the metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR1 can substitute for PF activation in induction of LTD (7, 8). mGluR1 activation elevates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (InsP3) (9, 10) and mobilizes calcium from intracellular stores (11–13). Mice lacking mGluR1 manifest motor deficits and lack LTD (14, 15). The presence of functional InsP3 receptors in intact Purkinje cells has been established (16–18), and mice lacking type 1 InsP3 receptors (the predominant form in Purkinje neurons) are ataxic and rarely survive (19). It has been suggested that the role of PFs in the induction of LTD is to release calcium from intracellular stores via InsP3 receptors (20). Here we directly study the role of InsP3 in modulation of synaptic strength by combining whole-cell patch clamp recordings with flash photolytic release of InsP3 in Purkinje neurons in cerebellar slices. Our results show that InsP3-evoked calcium release can substitute for activation of PFs and may play an important role in the induction of LTD in the cerebellum (also see ref. 34 for a preliminary report).

METHODS

Sagittal cerebellar slices (300 μm) were prepared as previously described (16, 21) from 9- to 20-day-old Sprague–Dawley rats. After 1-hr incubation at 34°C a slice was transferred to the experimental chamber on the stage of a Zeiss Axioskop and was continuously perfused with the extracellular solution at room temperature (20–24°C).

The composition of the extracellular solution was 125 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 11 mM glucose, 1.5 mM CaCl2, and 10 μM bicuculline. When gassed with 95% O2:5% CO2 the pH of the solution was 7.4. The composition of the intracellular solution was 145 mM K gluconate, 8 mM KCl, 3 mM MgATP, 10 mM Hepes (K), pH 7.2. Furaptra (500 μM; Molecular Probes), caged-InsP3 (150 μM; generous gift of Jeffrey Walker, University of Wisconsin), and heparin (Sigma) were introduced into cells via the patch pipette when indicated.

Slices were viewed with a Zeiss 63×, 0.9 NA infinity-corrected water immersion objective. The surfaces of identified Purkinje neurons were gently “cleaned” (21), and tight seal whole-cell patch clamp recordings (22) were made, by using pipettes with an electrical resistance of 1.5–2.5 MΩ. The series resistance on achieving whole-cell configuration was 4–6 MΩ and was compensated at least 60% by the amplifier circuitry of a home-made voltage clamp amplifier. The series resistance and membrane conductance were repeatedly estimated from −20 mV hyperpolarizing pulses. Cells were clamped at −70 mV unless otherwise stated and, with the solutions used, typically required less than −250 pA of holding current. Recording was terminated if the holding current exceeded −500 pA.

The “cleaning” pipette was connected to a stimulus isolation unit (Isolator-10, Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA) and was placed above the molecular layer and used to deliver 100-μs current pulses for synaptic stimulation. PFs were stimulated every 3 s, and the average of each 10 consecutive responses was recorded. A stable baseline was routinely obtained for >20 min before LTD induction achieved by either of two methods. The first consisted of flash photo-release of 40 μM InsP3 followed, 50 ms later, by depolarization of the Purkinje neuron to 0 mV for 50 ms (InsP3+ΔV). The second procedure, referred to as PF+ΔV, consisted of 30- or 100-s 1-Hz trains of concurrent PF stimulation and 50-ms depolarization of the Purkinje neuron to 0 mV.

Standard quantitative epifluorescence microscopy was used to measure the fluorescence emitted by the calcium indicator, furaptra, and thence to estimate [Ca2+]i. A 425-nm narrow-band filter was used for excitation, and a wide-band 510-nm filter to collect the emitted light. Furaptra, when entirely saturated with calcium ions, emits negligible fluorescence when excited at 425 nm (16, 17, 23). Fmax (fluorescence emitted by the indicator when fully saturated by calcium) was assumed to be zero. Given furaptra’s low affinity for calcium ions (Kd = 48 μM under our experimental conditions; refs. 16 and 17) at resting cellular calcium concentration (≈100 nM) the fraction of calcium carrying indicator is negligible. The resting level of fluorescence emitted by the indicator, after background correction, was taken to represent Fmin (fluorescence emitted by the indicator in zero calcium). With these assumptions, [Ca2+]i was estimated from the equation [Ca2+] = Kd(F − Fmin)/(Fmax − F), where F is the background-corrected observed fluorescence and Fmax is zero, as stated above. Fluorescence was measured either with a photodiode that collected light from the entire cell with millisecond time resolution, or with a cooled charged-coupled device imaging camera (EEV Chip, Frame transfer mode, Princeton Instruments, Trenton, NJ) set to integrate the fluorescence and record a 384 × 288-pixel frame every 300 ms.

A modified 238 Chadwick Helmuth Strobex (El Monte, CA) xenon arc lamp produced UV pulses of ≈1 ms in duration to photo-release known quantities of InsP3 in the cytosol as described earlier (24). A 370-nm-long pass 45° dichroic filter allowed the UV pulse to follow the same light path as did the fluorescence excitation light. Up to ≈65% photolysis of caged InsP3 could be achieved with a single pulse at full power. The flash lamp was triggered either manually or by the computer that controlled the voltage clamp. The extent of photolysis was calibrated by using a fluorescent pH indicator, BCECF, taking advantage of the stoichiometric release of a proton with ATP during photolysis of caged MgATP (25), which has the same photolytic efficiency as caged InsP3 (26) (for details see ref. 24).

RESULTS

We tested whether InsP3-evoked calcium release mimics PF activation in the induction of LTD by flash photo-releasing InsP3 from intracellular caged InsP3 (27). The amplitude of inward currents evoked by stimulation of PFs was measured in voltage-clamped Purkinje cells, and a baseline was obtained. Forty micromolars InsP3 photo-released in the cytosol with a 1-ms ultraviolet light pulse caused [Ca2+]i elevation in the soma as well as in the extensive dendritic tree (Fig. 1A). InsP3-evoked calcium release is quite fast, and [Ca2+]i reaches its peak in under 50 ms with 40 μM of InsP3 (16, 17). Concurrent with the rise in [Ca2+]i, the membrane resistance decreased, presumably because of opening of calcium-activated K+ and Cl− channels present in Purkinje neurons (16, 17). Resistance returned to its resting value, within a few seconds, following the same time course as the calcium transient (data not shown, but see ref. 17). To mimic activation of the CF, the Purkinje cell was depolarized to 0 mV for 50 ms, 50 ms after photo-release of InsP3 (procedure InsP3+ΔV). After the return of [Ca2+]i and resistance to their resting levels, the PF response showed 20–50% (31.4 ± 8.4% mean ± SE) depression in 7 of 11 cells (Fig. 1 B and C). The reduction in PF response lasted for the duration of the experiment (up to 90 min) and was not because of a change in the electrical access resistance, which was monitored throughout. The kinetics of the PF response was not altered after induction of LTD (Fig. 1B). These experiments demonstrate that InsP3-evoked calcium release can substitute for activation of PFs in the induction of LTD. In the four cells where InsP3+ΔV did not produce marked depression of the PF responses, 30-s trains of the PF+ΔV procedure also failed to elicit LTD. Flash photolytic release of InsP3 without depolarization occasionally resulted in LTD, but was not as effective (5–25% depression) or reproducible as that combined with depolarization (data not shown).

Figure 1.

(A) The fluorescence emitted by the calcium indicator furaptra was integrated every 300 ms and calibrated to yield estimates of [Ca2+]i. Shown is [Ca2+]i (color calibration bar in μM) in a Purkinje neuron 50 ms after photo-release of 40 μM InsP3. Calcium is mobilized in the soma as well as in the extensive dendritic tree. (Bi) Representative PF-evoked excitatory synaptic current record in a voltage-clamped Purkinje neuron. (Bii) After a stable baseline, 40 μM InsP3 was photo-released in the cytosol with a 1-ms pulse of UV light. Fifty milliseconds after the flash the cell was depolarized to 0 mV for 50 ms. Stimulation of PFs after coincident InsP3+ΔV resulted in smaller inward currents. (Biii) Scaling of the PF-evoked synaptic currents after LTD to the same amplitude as that of control responses reveals that the kinetics of synaptic currents were not altered after LTD. Experiment JL245A. (C) Relative amplitudes of peak PF-evoked inward synaptic currents are plotted against time. Concurrent InsP3+ΔV, delivered at the time indicated by the arrow, reduced the amplitude of subsequent PF-evoked synaptic currents. Additional pulses of InsP3+ΔV resulted in much smaller reduction in the amplitude of the synaptic currents, although the InsP3-evoked calcium release was the same (data not shown). Experiment JN096A.

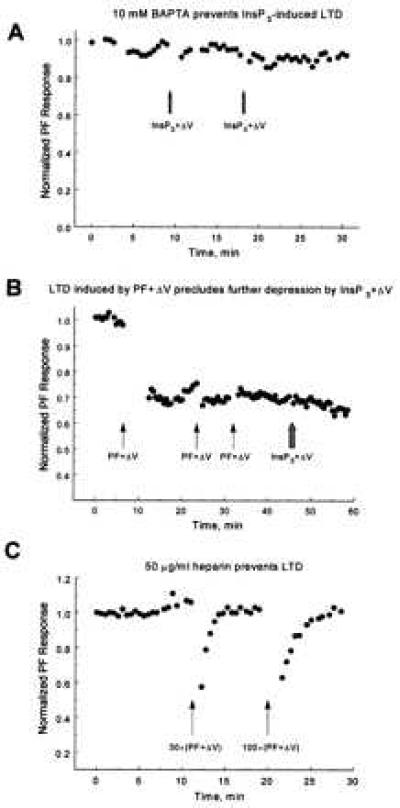

Inclusion of 10 mM 1,2-bis(2-amino phenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid in the patch pipette to buffer changes in [Ca2+]i prevented induction of LTD by InsP3+ΔV (Fig. 2A) in all three cells tested. This finding suggests that the ability of photo-released InsP3 to substitute for activation of PFs arises from its potency as a calcium-mobilizing agent rather than a nonspecific action.

Figure 2.

(A) Intracellular calcium buffering prevents LTD. A Purkinje neuron was voltage-clamped with a patch pipette filled with solution containing 10 mM 1,2-bis(2-amino phenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid. Two pulses of InsP3+ΔV (arrows) failed to induce LTD. Experiment JL255A. (B) Evidence of saturation. A 30-s train of PF+ΔV (arrow) was used to induce LTD. Two subsequent 30-s trains of PF+ΔV (second and third arrows) failed to induce additional depression as maximal depression was achieved with the first train. Photo-release of InsP3+ΔV (hashed arrow) also failed to induce additional depression, which suggests a common pathway for both protocols. (C) The InsP3 receptor antagonist heparin (50 μg/ml in the patch pipette) prevented induction of LTD by 30-s (first arrow) and 100-s (second arrow) trains of PF+ΔV, indicating that InsP3-evoked calcium release is required for induction of LTD under physiological conditions. The transient decreases in responses after the trains are because of increases in membrane conductance presumably caused by calcium-activated K+ and Cl− channels. In all other figures amplitude of synaptic currents are shown after return of the membrane conductance to its resting level. Experiment JL166A.

It has been shown that LTD induced by concurrent stimulation of PFs and CF saturates: repeated application of stimulation causes, maximally, 50% depression of the PF responses (see Fig. 2B). We tested whether LTD induced by repeated InsP3+ΔV also saturates near 50%. We find that succeeding InsP3+ΔV pulses resulted in relatively modest additional depression of the PF synaptic response† (Fig. 1C). The maximum depression achieved with repeated InsP3+ΔV pulses saturated and was always less than 60% (46.8 ± 8.1% mean ± SE; see for example Fig. 3B). Clearly substitution of InsP3-evoked calcium release for PF activation preserves the characteristic “saturation” of LTD.

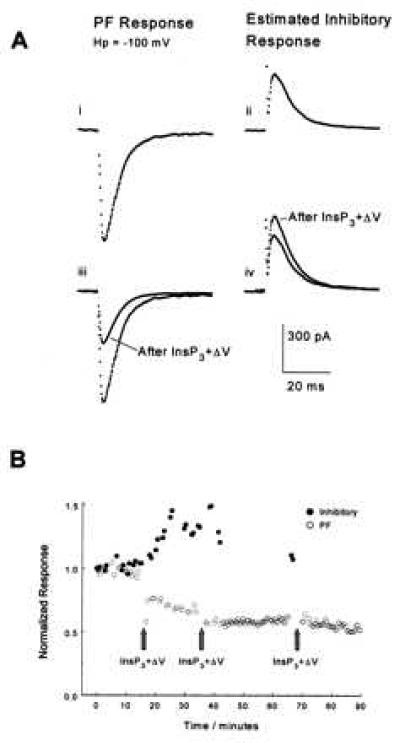

Figure 3.

(Ai) PF-evoked excitatory synaptic currents were recorded by clamping a Purkinje cell at the chloride reversal potential, −100 mV. (Aii) The “pure” contribution of inhibitory synaptic currents were estimated from currents recorded at −50 mV as described in the text. (Aiii) Concurrent photo-release of 40 μM InsP3 together with depolarization of the Purkinje cell to 0 mV for 50 ms decreased the amplitude of the PF-evoked synaptic current, and (Aiv) facilitated the amplitude of the inhibitory synaptic current. Qualitatively similar results were observed in three other cells. Experiment JL265A, cell no. 2. (B) Time course of normalized amplitudes of the PF-evoked excitatory (○) and inhibitory (•) synaptic currents of the experiment in A. InsP3+ΔV depressed the PF responses while increasing the inhibitory synaptic current. Subsequent pulses of InsP3+ΔV did not induce more than 50% depression of the excitatory synaptic currents.

An important question is whether LTD induced by InsP3-evoked calcium release uses the same molecular mechanism as LTD induced by PF+ΔV. We addressed this question by testing whether saturation of LTD by one protocol precludes induction of further depression by the other. Fig. 2B shows one of four experiments where, after PF responses were maximally reduced by 30-s trains of concurrent PF+ΔV, photo-release of InsP3+ΔV failed to cause additional depression of the PF synaptic responses, even though each flash photo-release of [Ca2+]i caused prominent calcium elevation. The reverse procedure was used in three other cells: after maximal LTD was induced by InsP3+ΔV, subsequent PF+ΔV activation failed to induce additional depression (data not shown). Thus maximal induction of LTD by either PF+ΔV or InsP3+ΔV precludes additional depression by the alternative protocol, suggesting that both procedures use a common pathway to induce depression of PF synaptic currents.

Whether LTD induction requires InsP3-evoked calcium release, disruption of the process should abolish it. To test this theory, we prevented calcium release by blocking InsP3 receptors with the competitive antagonist heparin (28–30). In all four cells tested 50 μg/ml of heparin in the intracellular patch pipette prevented induction of LTD by trains of PF+ΔV (Fig. 2C). Although this observation needs confirmation with a more specific InsP3 receptor antagonist or a functional antibody when these become available, it suggests that calcium release via InsP3 receptors plays a crucial role in the induction of LTD.

In addition to excitatory inputs, Purkinje neurons receive inhibitory inputs from interneurons. In his pioneering theory of cerebellar function, Albus argued that a stable learning process requires not only that excitatory parallel fiber inputs to Purkinje neurons be weakened, but also that inhibitory synaptic inputs be facilitated (3). Indeed, facilitation of inhibitory synapses has been demonstrated after induction of LTD (31, 32). It would be interesting to establish if this phenomenon, termed rebound potentiation (32), also occurs when LTD is induced by InsP3+ΔV. We tested this by monitoring the amplitude of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic currents in the same cell. A stimulation electrode was positioned just above a stellate cell in the molecular layer, and its current adjusted so that both the stellate cell and a few PFs were activated with each stimulus. The chloride concentration in the patch pipette was 8 mM to yield a reversal potential for γ-aminobutyric acid channels near −100 mV, and the Purkinje neuron was clamped at this potential. The inward synaptic current amplitude so recorded under these conditions is almost purely excitatory, carried by Na+ ions through glutamate-activated channels (Fig. 3A). To examine the inhibitory Cl− current, the cell was clamped at −50 mV where chloride ions through γ-aminobutyric acid channels produce an outward current, which sums with the (now reduced) excitatory current, yielding a small net outward current. The amplitude of the inhibitory current was determined (Fig. 3A) by subtracting the easily calculated excitatory current contribution‡. This procedure allowed us to monitor the amplitude of both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic currents in the same cell. As expected for rebound potentiation, the amplitude of the inhibitory synaptic current increased after induction of LTD by InsP3+ΔV (Fig. 3). The potentiation of inhibitory currents by InsP3+ΔV in the same cell that undergoes LTD of PFs argues against a nonspecific effect of photo-releasing InsP3 (e.g., phototoxicity) on synaptic function.

DISCUSSION

The experiments reported here show that photo-release of InsP3, when combined with depolarization of the Purkinje cell, is effective and sufficient in producing a long-lasting depression in the amplitude of the PF-evoked excitatory synaptic currents, as well as rebound potentiation of inhibitory currents. LTD caused by InsP3 is calcium dependent and shares, at least in part, the same molecular machinery used by conventional procedures for LTD induction.

LTD of inotophoretically applied glutamate currents after photolytic release of InsP3 has been reported in cultured Purkinje neurons (33), although in this study activation of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors also was found to be necessary for induction of depression. We find photo-release of InsP3 together with depolarization of the cell to be sufficient for induction of LTD in Purkinje cells studied in acutely prepared cerebellar slices. It is not clear why activation of AMPA receptors is required for induction of depression of glutamate-evoked excitatory currents in cultured Purkinje cells, but not for induction of LTD in cells studied in acutely prepared slices. One explanation may be that properties of Purkinje cells alter in culture and that the requirement for activation of AMPA receptors may be a consequence of these changes in culture. Alternatively, however, we note that we have not been successful in obtaining reliable InsP3-evoked calcium responses in Purkinje cells with caged InsP3 supplied by Calbiochem (lots B08608 and 310292) (the caged InsP3 used for experiments reported in this paper was the generous gift of Jeffrey Walker). The caged InsP3 used for the experiments in cultured Purkinje cells was supplied by Calbiochem, and from the published work it is not clear whether its efficacy in mobilizing calcium in cultured Purkinje cells was rigorously evaluated.

In our experiments the pulse of UV light photolyzed InsP3 uniformly in the cell and resulted in large calcium transients in the soma and dendritic tree of Purkinje neurons. Of concern is that induction of LTD after photo-release of InsP3+ΔV is because of activation of a calcium-dependent process by the large InsP3-evoked rise in [Ca2+]i, and that under physiological conditions InsP3 is not used as the second messenger. However, the ability of the InsP3 receptor antagonist, heparin, to block induction of LTD by conventional methods (repeated activation of PFs+ΔV) suggests that InsP3-evoked calcium release plays an important role under physiological conditions and that calcium release from intracellular calcium stores via InsP3 receptors is essential for the induction of LTD in the cerebellum.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yale Goldman for allowing the use and modification of his flash lamp, Dr. Jeffrey Walker for a generous gift of caged InsP3, and Drs. Brian Salzberg and Paul De Weer for comments. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant NS 12547.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CF

climbing fiber

- PF

parallel fiber

- LTD

long-term depression

- InsP3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- [Ca2+]i

intracellular calcium concentration

Footnotes

In these experiments we were careful to allow re-equilibration time of caged InsP3 in the pipette with the cytosol after each pulse of UV light, so that successive InsP3-evoked calcium responses were similar to the first.

These experiments were carried out in the absence of bicuculline. At the end of each study 10 μM bicuculline was added to the extracellular solution to block inhibitory transmission, and the amplitude of the PF-evoked synaptic currents at various holding potentials was recorded. The amplitude of the PF-evoked currents reversed at a holding potential of 0 mV, and the current was a linear function of holding potential (−100 to +50 mV). The inward synaptic currents recorded at −100 mV were scaled by 0.5 to account for the change of driving force and subtracted from the net outward currents recorded at a holding potential of −50 mV to determine the amplitude of inhibitory synaptic currents.

References

- 1.Ito M. The Cerebellum and Neural Control. New York: Raven; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marr D J. Physiology. 1969;202:437–470. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1969.sp008820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albus J S. Math Biosci. 1971;10:25–61. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito M, Masaki S, Tongroach P. J Physiol. 1982;324:113–134. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakurai M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3383–3385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crepel F, Krupa M. Brain Res. 1988;458:397–401. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(88)90486-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vranesic I, Batchelor A, Gahwiler B H, Garthwaite J, Staub C, Knopfel T. NeuroReport. 1991;2:759–762. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199112000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuzaki M, Mikoshiba K J. Neuroscience. 1992;12:4253–4263. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04253.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kano M, Kato M. Nature (London) 1987;325:276–279. doi: 10.1038/325276a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Linden D J, Dickinson M H, Smeyne M, Conner J A. Neuron. 1991;7:81–89. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90076-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang P M, Bredt D S, Snyder S H. Science. 1990;249:802–804. doi: 10.1126/science.1975122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackstone C D, Supattapone S, Snyder S H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:4316–4320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Llano I, Dreessen J, Kano M, Konnerth A. Neuron. 1991;7:577–583. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90370-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abia A, Kano, Chen M C, Stanton M E, Fox G D, Herrup K, Zwingman T A, Tonegawa S. Cell. 1994;79:377–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conquet F, Bashir Z I, Davies C H, Daniel H, Ferraguti F, Bordi F, Franz-Bacon K, Reggiani A, Conde F, Collingridge G L, Crepel F. Nature (London) 1994;372:237–243. doi: 10.1038/372237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khodakhah K, Ogden D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4976–4980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.4976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khodakhah K, Ogden D. J Physiol. 1995;487:343–358. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang S S, Augustine G J. Neuron. 1995;15:755–760. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsumoto N, Nakagawa T, Inoune T, Nagata T, Tanako K, Takano H, Minowa O, Kuno J, Sakakibara S, Yamada M, Yoneshima H, Miyawaki A, Fukuuchi Y, Furuchi T, Okano H, Mikoshiba K, Noda T. Nature (London) 1996;379:168–171. doi: 10.1038/379168a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berridge M J. Nature (London) 1993;365:388–389. doi: 10.1038/365388a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edwards F A, Konnerth A, Sakmann B, Takahashi T. Pflügers Arch. 1989;414:600–612. doi: 10.1007/BF00580998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamill O P, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth F J. Pflügers Arch. 1981;391:85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konishi M, Hollingworth S, Harkins A B, Baylor S M. J Gen Physiol. 1991;97:271–301. doi: 10.1085/jgp.97.2.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khodakhah K, Armstrong C M. Biophys J. 1997;73:3349–3357. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78359-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Walker J W, Reid G, McCray J, Trentham D R. J Am Chem Soc. 1988;110:7170–7177. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker J W, Feeney J, Trentham D R. Biochemistry. 1989;18:3272–3280. doi: 10.1021/bi00434a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker J W, Somlyo A V, Goldman Y E, Somlyo A P, Trentham D R. Nature (London) 1987;327:249–252. doi: 10.1038/327249a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghosh T K, Eis P S, Mullaney J M, Ebert C L, Gill D L. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:11075–11079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi S, Somlyo A V, Somlyo A P. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;153:625–631. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81141-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Supattapone P F, Worley J M, Baraban S H, Snyder S. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:1530–1534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vincent P, Armstrong C M, Marty A. J Physiol. 1992;456:453–471. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kano M, Rexhausen U, Dreessen J, Konnerth A. Nature (London) 1992;356:601–604. doi: 10.1038/356601a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kasono K, Hirano T. NeuroReport. 1995;6:569–572. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199502000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khodakhah K. Biophys J. 1996;70:A196. [Google Scholar]