Abstract

Changes in the hemodynamic environment (e.g., hypertension, disturbed-flow conditions) are known to promote atherogenesis by inducing proinflammatory phenotypic alterations in endothelial and smooth muscle cells; however, the mechanisms underlying mechanosensitive induction of inflammatory gene expression are not completely understood. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 and -4 (BMP-2/4) are TGF-β superfamily cytokines that are expressed by both endothelial and smooth muscle cells and regulate a number of cellular processes involved in atherogenesis, including vascular calcification and endothelial activation. This review considers how hemodynamic forces regulate BMP-2/4 expression and explores the role of mechanosensitive generation of reactive oxygen species by NAD(P)H oxidases in the control of BMP signaling. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 1683–1697.

Introduction

In the past decades, it has been established that vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis develop in hemodynamically well-defined regions. The facilitating role of pressure/wall tension in this context is undeniable: despite uniform levels of circulating proatherogenic factors (LDL, homocysteine, cigarette smoke constituents, etc.), atherosclerosis is limited to arteries characterized by high pressure/wall tension, whereas it never develops in low-pressure vascular beds (pulmonary circulation, arterioles, or veins). Moreover, hypertension has been recognized as an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis. In the late 1960s, Caro et al. (11) also called attention to the association of low-shear-stress areas with early atherosclerotic lesion localization in human arteries. This led to the hypothesis that low time-averaged wall shear stresses, such as found at atherosclerosis-prone vascular curvatures and branch points, might promote the localized attachment and infiltration of platelets and monocytes as well as atherogenic lipoproteins into the arterial wall. This original working concept invoked rheologic factors per se as the critical determinant of vulnerability of the vessel wall.

During the last two decades, major refinements have emerged in our understanding of how hemodynamic forces regulate vascular homeostasis. It has become established that changes in hemodynamic forces acting on both endothelial and smooth muscle cells activate cellular signaling pathways, translating biomechanical stimuli into biologic responses. During normal vascular homeostasis, laminar shear stress maintains an antiinflammatory, antiatherogenic phenotype of endothelial cells. In contrast, adverse changes in the hemodynamic environment, in particular a combination of low shear stress and high pressure, elicit proinflammatory phenotypic changes favoring atherogenesis (including endothelial activation, proinflammatory cytokine expression, smooth muscle hypertrophy, hyperplasia, migration and differentiation, and extracellular matrix reorganization).

The mechanisms by which disturbed flow conditions and high pressure act as potent proatherogenic forces have been the subject of intense studies in this field (74, 75). This review focuses on the emerging evidence that reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a central role in vascular mechanotransduction and discusses the potential link between alterations in hemodynamic environment, expression of bone morphogenetic proteins, and vascular inflammation.

Activation of NAD(P)H Oxidases in Endothelial and Smooth Muscle Cells by Hemodynamic Forces

Potential vascular sources of ROS include NAD(P)H oxidase, nitric oxide synthase (NOS), xanthine oxidase, cytochrome P450, cyclooxygenase, and mitochondria. In recent years, increasing evidence has accumulated that production of ROS, particularly O2•− and H2O2, through activation of vascular NAD(P)H oxidases, plays a central role in vascular mechanotransduction. The activities of other oxidases in the vessel wall appear less likely to influence signaling systems under baseline physiologic conditions, although some of them may be also upregulated by adverse hemodynamic conditions (84). Endothelial and smooth muscle cells express different NAD(P)H oxidases that consist of multiple oxidase and regulatory subunits. In phagocytic cells, the gp91phox (Nox-2) oxidase subunit has been reported to be activated by stimulation of the assembly of p47phox, p67phox, and p40phox regulatory subunits and activation of the small G protein rac, which bind to the cell membrane–bound NOX-2-p22phox complex. Many of the NAD(P)H oxidase subunits expressed in neutrophils (p22phox, p47phox, p67phox, NOX-2, and Rac) are expressed in the vascular tissue. However, the vascular and neutrophil NAD(P)H oxidases differ: whereas the neutrophil oxidase releases large amounts of O2•− outside the cell in bursts, the vascular counterparts continuously produce low levels of O2•− in the intracellular compartment. In vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells, both Nox-2 and its homologues Nox-1 and Nox-4 subunits are expressed (37, 40, 127). Furthermore, vascular NAD(P)H oxidase activity is supported by both NADH and NADPH (37, 40, 89).

Several lines of evidence suggest that hemodynamic forces can either directly or indirectly activate vascular NAD(P)H oxidase-derived ROS production (74, 75). Ample indications suggest that hypertension is associated with an increased activity of vascular NAD(P)H oxidases [reviewed in references (9, 68, 130)]. Although earlier studies attributed this largely to circulating neurohumoral factors, such as angiotensin II (35, 91, 103), by now it has become evident that oxidative stress is present in virtually all forms of hypertension (4, 103), including low-renin hypertension (69, 112), despite differences in plasma levels of circulating vasoactive factors [for a detailed discussion of the topic, please see references (68, 127, 128)].

A primary role for high intraluminal pressure itself in the promotion of vascular NAD(P)H oxidase–dependent O2•− generation is supported by the observations that in rats with aortic banding, increases in vascular O2•− production are observed exclusively in blood vessels proximal to the coarctation that are exposed to high pressure, but not in distal normotensive vascular beds, despite the presence of the same circulating factors throughout the vascular tree (128). Direct evidence for high pressure–induced, NAD(P)H oxidase–dependent oxidative stress has come from studies showing that exposure of isolated arteries to high pressure in an organoid culture system elicited significant O2•− and H2O2 (Fig. 1) production (76, 127) and endothelial dysfunction (55). Short-term increases in pressure in vivo also impair endothelial function (23, 36, 67, 139) by activating ROS-dependent mechanisms (67). It is likely that cellular stretch due to increased wall tension is the primary mechanical stimulus for NAD(P)H oxidase activation, because exposure of isolated arterial rings to in vitro stretching also activates vascular NAD(P)H oxidase–dependent O2•− generation (97), mimicking the effects of high pressure. Moreover, increased production of ROS has been detected in cultured endothelial and smooth muscle cells subjected to in vitro stretching (39, 50, 51). Importantly, aging appears to potentiate high pressure–induced Nox activation and O2•− production in peripheral arteries (61). In whole vessels, mechanically induced ROS comprise not only O2•− but also H2O2 (21, 96), indicating that a significant portion of NAD(P)H oxidase–derived O2•− is likely dismutated by superoxide dismutase (SOD) isoforms, which vascular cells express abundantly.

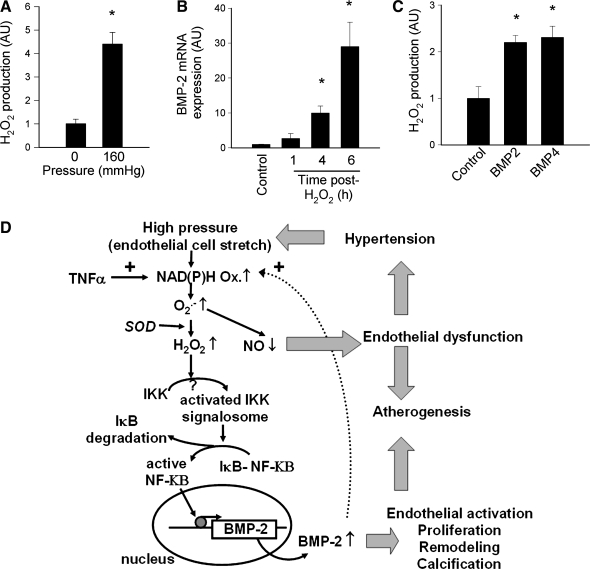

FIG. 1.

Mapping the relation between pressure, ROS production, and BMPs in the context of hypertensive vascular remodeling. (A) Exposure of isolated rat femoral arteries to high pressure (160 mm Hg) in vitro significantly increases vascular H2O2 generation (measured with the homovanillic acid/horseradish peroxidase method). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. n = 4–5 for each group; *p < 0.05 vs. control, #p < 0.05 vs. high-pressure treated). (B) Time course of H2O2 (10−4 M)-induced BMP-2 mRNA expression in CAECs (real-time QRT-PCR). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4 for each time point). Figures were redrawn based on data presented in reference (21). (C) Treatment of CAECs (24 h) with BMP-2 (10 ng/ml) and BMP-4 (10 ng/ml) significantly increases H2O2 production [measured with the DCF fluorescence method (129)]. (D) Proposed scheme for a common redox-sensitive pathway leading to activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB in endothelial cells induced by an increased H2O2 production due to the activation of the NAD(P)H oxidase by inflammatory cytokines and high pressure. Binding of NF-κB to its target sequences promotes the expression of BMP-2, which induces proatherogenic phenotypic changes in endothelial cells.

The underlying mechanisms by which high pressure/wall tension–related cell stretch elicits NAD(P)H oxidase activation probably involve increases in [Ca2+]i and phosphorylation and activation of PKCα (127). PKC-dependent serine phosphorylation of the regulatory p47phox subunit (126) results in its translocation from the cytosol to the membrane oxidase subunits (97), activating NAD(P)H oxidase function. The long-term presence of high pressure may also affect PKC expression in some vascular beds (98). It is of note that the activation of Nox-1 and Nox-4 in response to hemodynamic forces may differ. Nox-4 does not seem to be regulated by PKC phosphorylation of p47phox, and Nox-1 and Nox-4 are likely to be expressed in different cellular compartments (41, 49) [reviewed recently in reference (130)].

In addition to their role in pressure-induced signal transduction, ROS are likely to participate in the mechanotransduction of other modalities of blood flow, such as pulsatility and oscillatory shear stress. Previous studies have shown that pulsatile stretch increases O2•− production in human coronary artery smooth muscle cells (50) and in cultured rabbit aortas (115). Moreover, in porcine coronary arterioles exposed to pulsatile flow, the bioavailability of NO seems to be decreased as a result of increased O2•− generation (115). Disturbed flow conditions also were shown to increase endothelial ROS production (53, 72, 120), likely via stimulation of NAD(P)H oxidases (13, 58). Oscillatory shear stress is a particularly potent stimulus of O2•− production in cultured endothelial cells (24, 44, 58, 84).

Many existing hypotheses seek to explain how increased production of ROS affects vascular function and phenotype. According to the free radical theory of aging (43), chronic oxidative stress leads to the accumulation of oxidative damage to cellular constituents, resulting in a progressive decline in cellular function and ultimately to cellular senescence. Other laboratories emphasize the potential vasoactive effects of ROS, including degradation of vasodilator NO by O2•− (10) or vasomotor effects elicited by H2O2 or both (17, 81, 88, 142). In addition to eliciting macromolecular damage and exerting direct vasoactive effects, ROS can activate signaling pathways involved in vascular inflammation and atherogenesis. Importantly, accumulating evidence from experimental and clinical studies indicates that NAD(P)H oxidase activation plays a central role in atherogenesis and other pathophysiologic conditions, in part by regulating cell proliferation and inflammatory gene expression. This review discusses available data on the link between hemodynamic forces, NAD(P)H oxidase activation, and regulation of a novel class of proinflammatory cytokines that may play an important pathophysiologic role in atherogenesis.

Role of Bone Morphogenic Proteins in Vascular Physiology and Pathophysiology

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are members of the TGF-β superfamily. The first hint of the existence of BMPs came from the early clinical observations that bone formed in transplanted tissues. Subsequently it was discovered that a number of tissues possess various “osteogenic proteins,” or BMPs, that could induce new bone formation (132). After the purification and sequencing of the first BMPs in the late 1980s (82, 143), identification of the BMP family grew rapidly, and today it is known to comprise >30 cytokines, based on sequence homology. Although the name BMP is descriptive of one particular function, inducing ectopic bone or cartilage formation, it is quite misleading; BMPs play important roles in diverse cell types. Vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells both express BMP receptors and secrete BMPs (28, 110, 113, 114, 140). Among them, BMP-2 and BMP-4 (which are closely related by their amino acid sequence and act on the same receptor) have been shown to regulate a host of cellular functions (110, 114, 140, 153), including cardiovascular development (153), angiogenesis (1, 31, 47), neovascularization in tumors (71), vascular calcification (56, 108–110, 125, 137, 151, 152), and smooth muscle cell chemotaxis in response to vascular injury (140).

Role of BMPs in vascular inflammation and atherogenesis: role of Nox oxidases

Recent studies reported a striking upregulation of BMP-2/4 in atheroprone regions and atherosclerotic lesions (28, 113, 114, 118, 140). With in vitro and ex vivo approaches, BMP-2/4 also were shown to exert proinflammatory effects by inducing expression of adhesion molecules and enhancing monocyte adhesion (18, 113, 114). Prolonged BMP-4 infusion in C57Bl6 and apolipoprotein-null mice impairs endothelium-dependent vasodilation and induces arterial hypertension in an NAD(P)H oxidase–dependent manner (87). Activation of BMP signaling either by overexpression of the BMP-2/4 in vascular cells or by administration of recombinant BMPs results in endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress (by activating NAD(P)H oxidases), and an enhanced monocyte adhesiveness to the endothelium (18, 21, 113, 114). Vascular BMP signaling also has been linked to vascular calcification during atherogenesis (28, 52, 108, 110) and calciphylaxis (38), as well as to calcific stenosis of the aortic valves (90, 117, 145).

Aging is known to increase the risk for atherosclerosis by promoting vascular inflammation and upregulating Nox-oxidase–derived ROS production (22). It has been proposed that alterations in the vascular expression/activity of BMP antagonists may lead to unopposed BMP-2 activity in aging (118), which may contribute to age-related oxidative stress and promote arterial calcification. BMP-2/4 is thought to signal primarily by activating the mothers against decapentaplegic (Smad) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, although evidence suggests that BMP-2/4 may also activate NF-κB (18, 114). In that regard, it is important that aging is known to increase basal NF-κB activity in the vasculature, which may sensitize endothelial cells to the proinflammatory effects of BMPs (22). Future studies should elucidate the role of BMP-receptor subtypes and the interaction between downstream signaling mechanisms induced by BMPs, which mediate their proinflammatory effects.

Many lines of evidence thus suggest that BMPs may function as proinflammatory, prohypertensive, and proatherogenic mediators in the vessel wall. So far, our understanding of the factors that regulate vascular BMP-2/4 expression supports this premise. For example, we have shown that in coronary arterial endothelial cells, expression of BMP-2 is upregulated by proinflammatory stimuli, such as TNF-α and H2O2, by activation of NF-κB (18, 21). Accordingly, in hyperhomocysteinemia, coronary artery inflammation and upregulation of TNF-α is associated with an increased BMP-2 expression (126). Type 2 diabetes also is associated with induction of BMP-2 expression and activation of BMP-2–dependent Msx2-Wnt programs in the aorta that contribute to aortic calcium accumulation (2). Importantly, aortic BMP-2 expression could be attenuated by treatment with the TNF-α–neutralizing antibody infliximab (2). Because of the central role of hemodynamic forces in atherogenesis, our review focuses on the role of shear stress and pressure/wall tension in regulation of vascular BMP-2/4 expression.

Role of BMPs in vascular development, angiogenesis, and stem cell commitment

Convincing data show that BMPs are involved in embryonic and adult blood vessel formation in health and disease (25, 47, 71, 93, 94, 105, 154). In particular, the involvement of the BMP-regulated Id family of helix–loop–helix transcription factors in angiogenesis has been investigated extensively. Nevertheless, some controversy exists regarding differences between BMP-2 and BMP-4 on vascular cell proliferation and the different roles that these BMPs my play in endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cell physiology. Endothelial progenitor cells express BMP-2/4 and BMP receptors (111). However, published data suggest that BMP-2 enhances commitment of mesodermal cells to a cardiomyogenic fate (65, 80), whereas BMP-4 favors endothelial commitment of embryonic stem cells (138). Such BMP-dependent signaling pathways involved in embryonic development can be reactivated in adults and may thus contribute to the reparative effects of progenitor cell therapy after myocardial infarction and critical leg ischemia.

Conversely, the role of BMPs in NAD(P)H oxidase activation during angiogenesis and inflammatory gene expression in endothelial progenitor cells is poorly understood. Endothelial progenitor cells exhibit notable antioxidant defenses (27, 46), yet under conditions of increased oxidative stress, their function seems to be compromised (12, 59). In particular, increased NAD(P)H oxidase activation has been linked to loss of endothelial progenitor cell function and impaired postischemic neovascularization in diabetes (29) and in hypertension (150). It is thought that reduction of stem cell number or activity can contribute to cardiovascular aging and impaired angiogenesis in aged mammals, and considerable evidence indicates that increased production of ROS, in part due to the upregulation of NAD(P)H oxidases, underlies cellular dysfunction in the aged cardiovascular system [reviewed recently elsewhere (22)]. Further studies are evidently needed the better to elucidate the link between BMPs and NAD(P)H oxidase activation in endothelial progenitor cells under these pathophysiologic conditions.

Differential prooxidant and prohypertensive effects of BMPs in the pulmonary and systemic circulation

Genetic analysis of patients with primary pulmonary hypertension indicates that BMP signaling plays an important protective role in the pulmonary circulation. Studies in the last decade have shown that multiple loss-of-function mutations affecting BMP receptors (in both bmpr2 and alk1 genes) (26, 57, 70, 83, 123, 124) lead to monoclonal endothelial cell growth in plexiform lesions in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (73, 134). Although it is now clear that mutations in the BMP receptors can predispose to pulmonary hypertension, why such mutations in the germline (i.e., passed along to all somatic cells from the germinative cells) predispose only the pulmonary arteries but not systemic arteries to hypertensive disease has yet to be resolved.

It is believed that in pulmonary arteries, BMP signaling exerts important vasoprotective effects controlling the balance between proliferation and activation of apoptosis in endothelial and smooth muscle cells (31, 32, 42, 101, 102, 122). Importantly, recent experimental studies demonstrated that the expression and function of the BMP/Smad signaling axis is perturbed in secondary pulmonary hypertension as well (92). Thus, altered BMP signaling may contribute to the pathogenesis of both primary and secondary forms of pulmonary hypertension. In contrast, BMP-2 and BMP-4 function as prooxidant and prohypertensive mediators in systemic arteries (18, 64, 87, 113, 131), suggesting that BMP signaling plays different roles in the pulmonary and systemic circulations. Indeed, recent findings demonstrate that whereas BMP-4 elicits significant endothelial dysfunction and NAD(P)H oxidase activation in the systemic arteries, activating NF-κB and increasing monocyte adhesiveness, the pulmonary arteries are completely protected from such adverse functional effects (19). We attribute the lack of BMP-4–induced endothelial activation in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells to the superior resistance of these cells to the prooxidant effects of BMP-4 rather than to a lower expression of NAD(P)H oxidase in the pulmonary vasculature (19). Importantly, pulmonary arteries are known to be resistant to atherogenesis. Moreover, it is likely that differential effects of BMP-4 on NAD(P)H oxidase activity are responsible for the selective systemic (but not pulmonary) hypertension induced by high circulating levels of BMP-4 (87). Previous findings showed that in endothelial cells from the systemic circulation, BMPs activate NAD(P)H oxidase via a pathway that involves PKC (18), and evidence exists of association of the BMP-receptor complex with PKC (45). Hence, the lack of BMP-4–induced NAD(P)H oxidase activation in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells could be due to the differential role of PKC in BMP signaling in pulmonary and systemic arteries. It is also possible that subsets of BMP receptors and modulators of BMP signaling (BMP antagonists, co-receptors, etc.) are expressed differentially in systemic and pulmonary endothelial cells, which would activate discrete signaling pathways (19). Further studies are needed to determine which receptor is responsible for NAD(P)H oxidase activation in endothelial cells from systemic arteries and whether the divergence in BMP-induced ROS generation between systemic and pulmonary cells can be explained by the differential expression of BMP receptors and/or their downstream targets.

Regulation of BMP-2/4 Expression by Pressure/Wall Tension

Regulation of vascular BMP expression by oxidative stress and inflammatory stimuli prompted the speculation that proatherogenic hemodynamic forces that increase endothelial ROS production may also regulate BMP-2/4 expression. We demonstrated that increased wall tension/high intraluminal pressure is sufficient to induce BMP-2 expression in vitro, in the absence of vasoactive circulating factors (21). This finding has been confirmed by the observations that BMP-2 is upregulated in forelimb arteries of aortic banded rats, which are exposed to high pressure and exhibit an increased ROS production (128), whereas normotensive arteries located downstream from the coarctation (but exposed to the same circulating factors) exhibit a normal phenotype (21).

Strong evidence indicates that NF-κB plays a central role in the regulation of endothelial BMP-2 expression. Increased DNA-binding activity of NF-κB was shown to increase in in vivo models of hypertension (3) and in cultured endothelial and smooth muscle cells exposed to cyclic stretch (15, 51). Furthermore, NF-κB binding site(s) are present in the promoter region of the rat BMP-2 gene and in the 5' flanking region of the BMP-2 gene in mouse chondrocytes (34). The NF-κB binding site is localized in an evolutionary highly conserved region of the BMP-2 promoter (21), which explains the similar NF-κB–dependent regulation of BMP-2 expression in human and rat endothelial cells (18, 21). However, the promoter regions of the human and mouse BMP-4 genes differ from their BMP-2 counterparts because they lack an NF-κB binding site (48). This could account for the preferential regulation BMP-2 by TNF-α and H2O2 (18, 21). Hence, TNF-α is known to induce BMP-2 in endothelial cells through NAD(P)H oxidase–derived H2O2 production (18). Previous studies by our laboratories and others also demonstrated that high pressure similarly activates NAD(P)H oxidase, increasing vascular O2•− and H2O2 production that leads to NF-κB activation (21, 78, 79) and BMP-2 overexpression (21). It seems that high pressure/cell stretch elicits rapid degradation of the redox-sensitive NF-κB inhibitor IκBα (21, 78), which unmasks the nuclear localization sequence on NF-κB, allowing its nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity. A consequence of pressure-dependent upregulation of BMPs in the vascular wall, downstream of NAD(P)H oxidase and NF-κB activation, was shown to be endothelial activation (113, 114).

Correspondingly, a recent study demonstrated that prolonged exposure of cultured arteries to high pressure results in enhanced monocyte adhesion to the endothelium (104). Thus, it is likely that pressure-induced upregulation of BMP-2 and other related cytokines (79) will contribute to/enhance endothelial activation in hypertension and atherosclerosis.

Interestingly, pressure- or stretch-induced increased expression of the BMP-related cytokine TGF-β has been documented in blood vessels (119), and mechanosensitive expression of BMPs has been shown previously in bone (86, 95) and chondrocytes (144). Nevertheless, we recently found that TNF-α did not increase BMP-2 expression in vascular smooth muscle cells (18). Because TNF-α elicits comparable NF-κB activation in endothelial and smooth muscle cells (18), we speculate that differences in factors that lie downstream from NF-κB (e.g., differential expression of cell-specific coactivators) may be responsible for this phenomenon. It is of note that VEGF was likewise shown to upregulate BMP-2 in cultured human dermal microvascular endothelial cells, but not in lymphatic endothelial cells (133). Although this finding raised the possibility that regulation of BMP-2 expression may differ between endothelial cells from different organs, we found that basal BMP-2 expression was comparable in vessels from various systemic vascular beds (18), and that TNF-α elicited similar BMP-2 induction in human umbilical vein endothelial cells and coronary arterial endothelial cells (18, 21). Hence, BMP-2 induction by mechanical or inflammatory factors may be more complex than initially anticipated.

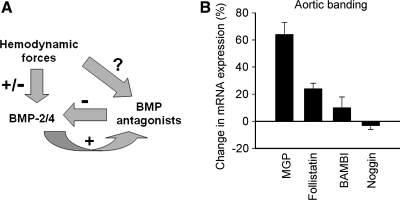

In various tissues, the actions of BMPs can be antagonized by proteins that block BMP signal transduction at multiple levels, such as pseudoreceptors, inhibitory intracellular binding proteins, and factors that induce BMP ubiquitination. A large number of extracellular proteins that bind BMPs and prevent their association with signaling receptors have emerged, including noggin, chordin, BAMBI (BMP and activin membrane-bound inhibitor), matrix Gla protein (MGP), and follistatin. Many of these BMP-binding proteins can be expressed in vascular tissues (6, 14, 16, 54, 60, 106, 107, 116, 146–149), although their roles in the regulation of vascular BMP signaling is not yet completely understood (131). For example, BMPER (bone morphogenetic protein–binding endothelial cell precursor–derived regulator) is a secreted protein that directly interacts with BMP-2 and BMP-4 and modulates BMP-2/4–induced signaling pathways in endothelial cells (47, 93, 154). MGP is thought to prevent vascular calcification by binding BMP4 (146) and BMP2 (135, 136). Conversely, the expression of BMP antagonists is regulated by BMPs (14, 121, 147, 148), pointing to a local feedback mechanism to modulate the cellular activities of BMPs. It is likely, though, that increased expression of BMP-2/4 coupled with decreased BMP antagonist expression has additive effects. Atherogenic stimuli such as TNF-α and oxLDL appear to regulate the expression of BMP antagonists in endothelial cells (16), and altered expression of BMP antagonists has been demonstrated in atherosclerotic lesions (107). Importantly, some studies suggest that BMP antagonists such as MGP (Fig. 2) and noggin (54) may be also regulated by hemodynamic forces.

FIG. 2.

Interactions between BMPs and their antagonists in hypertension. (A) Proposed scheme showing that hemodynamic forces may regulate the expression of both BMP-2/4 and BMP antagonists in vascular cells, which together will determine BMP activity in the vasculature. (B) High pressure may alter the expression of BMP-binding proteins in coronary arteries of aortic banded rats (n = 3). Data are expressed as relative changes in mRNA expression, as compared with vessels of sham-operated rats (n = 5).

The mechanisms underlying the transcriptional regulation of BMP antagonists in vascular cells have not yet been explored. Studies suggesting that the cAMP/PKA pathway may be involved in the regulation of BMP antagonists MGP (33) and follistatin (141) in nonvascular cells raise the interesting possibility that BMPs and BMP antagonists may be regulated by similar cellular signals.

Regulation of BMP-2/4 Expression by Shear Stress

Expression of BMP-4 in the vasculature is primarily localized to the endothelial cells, which are the primary sensors of changes in shear stress due to altered hemodynamics. At present, it is not well understood whether alterations in shear stress (either via direct transmission of the mechanical force by cellular connections and the extracellular matrix or indirectly via endothelium-derived paracrine mediators) induce transcriptional changes of BMPs, BMP receptors or modulators of BMP signaling pathways in the smooth muscle cells underlying the vascular endothelium. Nevertheless, the first indication that shear stress may control BMP-4 expression in endothelial cells came from microarray studies conducted to identify proatherogenic genes whose expression may be regulated by laminar flow (7, 113, 114). Solid evidence indicates that atheroprotective laminar flow/shear stress transcriptionally downregulates BMP-4 expression in multiple endothelial cell types from different species, whereas it does not affect BMP-2 transcript levels (20, 113).

Differential regulation of BMP-4 and BMP-2 was also substantiated in ex vivo intact artery and in vivo animal models of high flow (20), showing that shear stress is an important regulator of BMP-4 expression both in conduit arteries and in microvessels. Shear-dependent regulation of BMP-4 was further emphasized by a recent study showing low transcript levels of BMP-4 in protected, high-shear regions of the aortic valve, in contrast with abundant endothelial expression of BMP-4 in low-flow, calcification-susceptible valvular regions (8). It is known that laminar shear stress activates multiple redox-sensitive signaling pathways in endothelial cells [reviewed in references (74, 75, 77)], but the role of these pathways in shear-dependent regulation of BMP-2/4 expression is not well understood. Instead, in this review, we focus on the recently discovered roles of the shear stress–activated cAMP/PKA and ERK signaling pathways in regulating BMP-4 expression in endothelial cells.

Role of the cAMP/PKA pathway

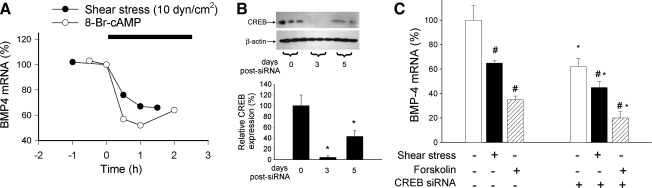

Recently, we found that inhibition of the cAMP/PKA pathway prevents the downregulation of the BMP-4 gene in endothelial cells exposed to shear stress (20). The inhibitory effect of shear stress on BMP-4 expression also was mimicked by the exogenous administration of an adenylate cyclase activator, a cAMP analogue, or a PKA activator (Fig. 3) (20). Although shear stress–induced production of cAMP is generally considered to derive from the autocrine effect of prostaglandins, and prostaglandins can downregulate BMP-4 (Ungvari, unpublished observation, 2006), this is likely not to be the case in sheared endothelium because downregulation of BMP-4 is maintained even in indomethacin-treated cells (20). Previous studies using magnetic RGD peptide–coated microbeads demonstrated that shear-induced mechanical activation of integrin-β leads to significant increases in intracellular cAMP (85), probably as a result of direct activation of adenylate cyclase. Moreover, cAMP is known to bind to the regulatory subunit of PKA, activating the enzyme, and recent data suggest that PKA is activated by shear stress (5, 20). A central role of PKA signaling is supported by the findings that pharmacologic or molecular inhibition of PKA prevents shear stress– and forskolin-induced downregulation of BMP-4 (20). It is also important to note that the mammalian BMP-4 gene structure is very similar to the Drosophila homologous gene decapentaplegic (dpp). During limb development, dpp expression is inhibited by the PKA pathway (62), whereas cells lacking PKA exhibit upregulation of dpp (99). Thus, PKA-dependent regulatory mechanisms controlling expression of BMP-4 appear to be conserved. Our recent data suggest that the cAMP/PKA pathway primarily decreases the transcription rate of the BMP-4 gene (rather than controlling the mRNA stability) (20).

FIG. 3.

Downregulation of BMPs by shear stress is independent of CREB. (A) Time course of BMP-4 expression downregulation in HCAECs in response to shear stress (10 dyn/cm2) or a cell-permeable cAMP analogue (0.3 mM 8-Br-cAMP). Analysis of mRNA expression was performed with real-time QRT-PCR. Figure is redrawn based on data from reference (129). (B) Representative Western blot and densitometric data showing the downregulation of CREB in HCAECs [achieved with RNA interference by using proprietary siRNA sequences and the Amaxa Nucleofector Technology; Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD, as we previously reported (18, 21)] as a function of time after transfection. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 3 for each data point). *p < 0.05. (C) Knockdown of CREB did not prevent shear stress–induced (10 dyn/cm2, for 2 h) and forskolin-induced (2 h) changes in BMP-4 expression in HCAECs (on day 3 after transfection). Analysis of mRNA expression was performed with real-time QRT-PCR. β-actin was used for normalization. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4 for each group). *p < 0.05 vs. no siRNA, #p < 0.05 vs. no shear stress/no forskolin.

Finally, despite the similar biologic roles of BMP-4 and BMP-2, the transcriptional regulation of these two cytokines by shear stress is again markedly different; activation of the cAMP/PKA pathway did not affect endothelial BMP-2 expression (20).

We recently reported that in human coronary arterial endothelial cells, both shear stress and cAMP analogues resulted in phosphorylation and activation of CREB, which were prevented by inhibition of PKA (20). The binding of phosphorylated CREB to the cAMP-responsive element (CRE) controls gene transcription (activation or suppression of transcription, depending on the target gene). It is significant that CRE sites have been found in the promoter region of many genes that respond to mechanical stimuli and may also exist in the BMP-4 promoter. On the basis of these considerations, we hypothesized that CREB would participate in BMP-4 regulation (20). Contrary to our prediction, however, we recently found that knockdown of CREB decreased basal BMP-4 expression in endothelial cells but it did not prevent shear stress– or forskolin-induced downregulation of BMP-4 (Fig. 3). These data suggest that CREB is a positive regulator of BMP-4 expression and that the downregulation of BMP-4 by shear stress is mediated via a cAMP/PKA-dependent but phosho-CREB–independent signal-transduction pathway.

Role of MAP kinase activation

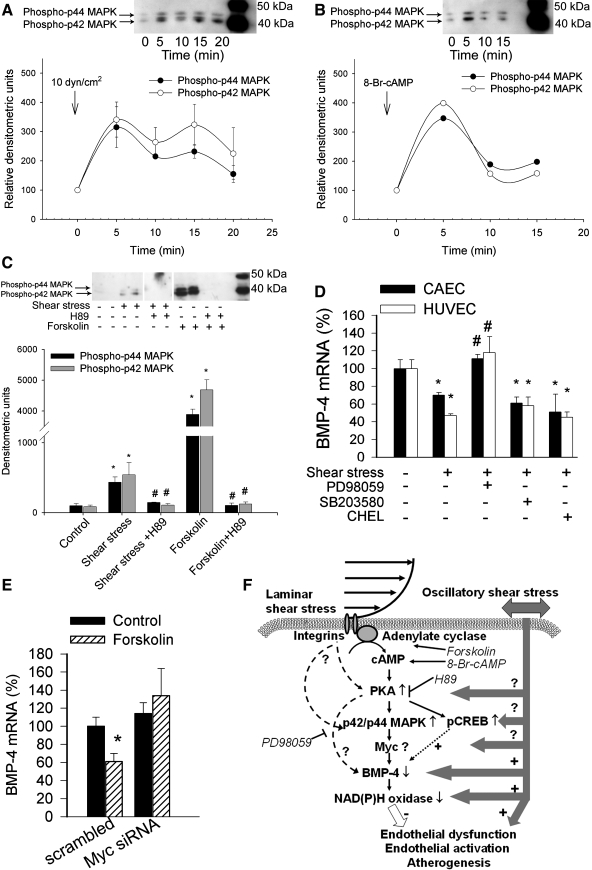

Previous studies provided ample evidence that exposure of endothelial cells to laminar shear stress activates p42/44 MAPK in a time-dependent manner (63, 100), we recently confirmed (Fig. 4A and C). Growing evidence suggests crosstalk between cAMP/PKA and ERK signaling in various cell types; in coronary arterial endothelial cells, cAMP and forskolin can activate p42/44 MAPK, and inhibition of PKA prevents both shear stress– and forskolin-induced activation of p42/44 MAPK (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that p42/44 MAPK is a critical downstream effector in the shear stress–activated cAMP/PKA pathway in endothelial cells, in line with the finding that inhibition of p42/44 MAPK (but not the p38 MAPK or PKC) prevented shear stress–induced downregulation of BMP-4 (Fig. 4D). Once activated, p42/44 MAPK is known to translocate to the nucleus and phosphorylate a number of different transcription factors (30), many of which have putative binding sites in the promoter region of the BMP-4 gene. At present, the MAPK-dependent transcription factor(s) lying downstream target of the cAMP/PKA pathway that downregulates the expression of BMP-4 in response to shear stress is unknown. Because knockdown of Myc (but not Sp-1 or p53) apparently attenuates the effect of forskolin on endothelial BMP-4 expression (Fig. 4E) and Myc-binding sites are conserved among the promoter region of human, baboon, cow, bat, mouse, and rat BMP-4 orthologues (66), future studies should characterize the role of Myc in detail in the regulation of BMP-4 expression in endothelial cells.

FIG. 4.

Downregulation of BMPs by shear stress implicates ERK1/2 and Myc. (A, B) Representative Western blots and densitometric data (below) showing the time course of p42/44 MAP kinase phosphorylation in shear stress–exposed (10 dyn/cm2; A) and 8-Br-cAMP–treated (B) human coronary arterial endothelial cells (HCAECs). (C) Representative Western blot and densitometric data (below) showing the effect of pretreatment with the PKA inhibitor H89 (10 μM) on shear stress–induced (10 dyn/cm2, 10 min) and forskolin-induced (10 μM, for 10 min) phosphorylation of p42/p44 MAP kinase in HCAECs. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. static control; #p < 0.05 vs. shear stress exposed. (D) Effect of pretreatment with inhibitors of the p42/p44 MAP kinase (PD98059, 10 μM), p38 MAP kinase (SB203580, 10 μM), or PKC (chelerythrine, 10 μM) on shear stress–induced (10 dyn/cm2, for 2 h) downregulation of BMP-4 expression in HCAECs and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs. static control; #p < 0.05 vs. shear stress exposed. (E) Effect of pretreatment with anti-Myc siRNA on forskolin-induced changes in BMP-4 expression in HCAECs (on day 3 after transfection). Analysis of mRNA expression was performed with real-time QRT-PCR. β-actin was used for normalization. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4 for each group). *p < 0.05. (F) Proposed scheme for the mechanism by which shear stress activates the cAMP/PKA pathway and regulates the expression of BMP-4 in the vascular endothelium. Because BMP-4 elicits endothelial activation and vascular calcification, the model predicts that cAMP/PKA-mediated inhibition of BMP-4 expression contributes to the antiatherogenic and vasculoprotective effects of laminar shear stress.

Role of oscillatory flow and NAD(P)H oxidase activation

In contrast with the effects of laminar shear stress, disturbed flow conditions, such as oscillatory shear stress, upregulate BMP-4 expression in endothelial cells (113, 114). Some evidence suggests that enhanced ROS production by NAD(P)H oxidase contributes to this response (113, 114). Further studies are clearly needed to elucidate the role of the cAMP/PKA pathway, CREB activation, ERK-dependent signaling mechanisms, or a combination of these effects on oscillatory shear stress. The significance of the upregulation of BMP-4 expression by disturbed hemodynamic conditions is also supported by the finding that BMP-4 protein is expressed in the endothelial cells overlying early atherosclerotic lesions but not in those that line uninjured human coronary arteries (113, 114). Based on the findings that ICAM-1 expression is increased in human coronary arteries in endothelial regions that express BMP-4 (113, 114) and that BMP-4 elicits monocyte adhesiveness in vitro (18, 113, 114), one can consider BMP-4 a master regulator of mechanosensitive endothelial activation. Many data presented in the present review uphold this hypothesis, which is further supported by a recent report that exposure of the aortic surface to pulsatile shear stress increased expression of the inflammatory markers VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in a BMP-4–dependent manner (117). Dr. Hanjoong Jo's laboratory (14) recently showed that healthy endothelial cells can co-express BMP antagonists along with BMP-4 in response to disturbed flow conditions, suggesting that these antagonists can play a negative-feedback role against the inflammatory response of BMP-4. It has yet to be elucidated how endothelial expression of BMP antagonists is altered in pathophysiologic conditions (e.g., diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hyperhomocysteinemia), which are known to promote atherogenesis.

Perspectives

Taken together, we propose that hemodynamic forces (pressure/wall tension and shear stress) regulate expression of vascular BMP-2/4 in endothelial and smooth muscle cells. As shown in Fig. 1D, high pressure/increased wall tension elicits increases in [Ca2+]I and PKC activation, stimulating Nox-dependent O2•− and H2O2 production. Increased cytosolic ROS levels lead to NF-κB activation, which upregulates BMP-2 expression. Conversely, atheroprotective laminar shear stress activates the cAMP/PKA and p42/44 MAP kinase pathway, which reduces BMP-4 expression in endothelial cells (Fig. 4F). Laminar shear stress also stimulates eNOS-dependent production of NO, which exerts vasodilatory, antiproliferative, and antiinflammatory effects on the smooth muscle cells. Because BMP-4 activates NAD(P)H oxidases and elicits endothelial dysfunction, monocyte adhesiveness to the endothelium, and vascular calcification, the model predicts that cAMP/PKA-mediated inhibition of BMP-4 expression contributes to the multifaceted antiatherogenic and vasculoprotective effects of laminar shear stress. In contrast, oscillatory/pulsatile shear stress increases Nox-derived ROS generation, decreasing the bioavailability of NO and upregulating BMP-4. Persistently disturbed hemodynamic conditions may also lead to the upregulation of paracrine signaling systems (including the local renin–angiotensin system and TNF-α production) that may also regulate BMP expression. Further studies are needed the better to elucidate (a) the downstream signaling pathways and target genes induced by BMPs in endothelial cells; (b) the role of BMPs in vascular remodeling induced by changes in the hemodynamic environment; (c) the differential redox-sensitive regulation of BMPs in endothelial and smooth muscle cells, characterizing the factors involved in their transcriptional regulation; and (d) the differences in BMP expression and regulation between systemic arteries (high pressure and atheroprone) and pulmonary arteries (low pressure, resistant to atherosclerosis, affected by BP-receptor mutations in primary pulmonary hypertension).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the American Heart Association (0430108N; 0435140N), the National Institutes of Health (HL077256; HL-43023), the American Diabetes Association, and by Philip Morris U.S.A. and Philip Morris International, Inc.

Abbreviations

BAMBI, BMP and activin membrane-bound inhibitor; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MGP, matrix Gla protein; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; NOX, NAD(P)H oxidase; PKC, protein kinase C; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SOD, superoxide dismutase; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

References

- 1.Abe J. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) family, SMAD signaling and Id helix-loop-helix proteins in the vasculature: the continuous mystery of BMPs pleotropic effects. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2006;41:4–7. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Aly Z. Shao JS. Lai CF. Huang E. Cai J. Behrmann A. Cheng SL. Towler DA. Aortic Msx2-Wnt calcification cascade is regulated by TNF-alpha-dependent signals in diabetic Ldlr-/- mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2589–2596. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.153668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ammarguellat FZ. Gannon PO. Amiri F. Schiffrin EL. Fibrosis, matrix metalloproteinases, and inflammation in the heart of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats: role of ET(A) receptors. Hypertension. 2002;39:679–684. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.103481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beswick RA. Dorrance AM. Leite R. Webb RC. NADH/NADPH oxidase and enhanced superoxide production in the mineralocorticoid hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 2001;38:1107–1111. doi: 10.1161/hy1101.093423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boo YC. Sorescu G. Boyd N. Shiojima I. Walsh K. Du J. Jo H. Shear stress stimulates phosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase at Ser1179 by Akt-independent mechanisms: role of protein kinase A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3388–3396. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108789200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bostrom K. Zebboudj AF. Yao Y. Lin TS. Torres A. Matrix GLA protein stimulates VEGF expression through increased transforming growth factor-beta1 activity in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:52904–52913. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406868200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks AR. Lelkes PI. Rubanyi GM. Gene expression profiling of human aortic endothelial cells exposed to disturbed flow and steady laminar flow. Physiol Genomics. 2002;9:27–41. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00075.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butcher JT. Tressel S. Johnson T. Turner D. Sorescu G. Jo H. Nerem RM. Transcriptional profiles of valvular and vascular endothelial cells reveal phenotypic differences: influence of shear stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:69–77. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000196624.70507.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cai H. Griendling KK. Harrison DG. The vascular NAD(P)H oxidases as therapeutic targets in cardiovascular diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2003;24:471–478. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cai H. Harrison DG. Endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases: the role of oxidant stress. Circ Res. 2000;87:840–844. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.10.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caro CG. Fitz-Gerald JM. Schroter RC. Arterial wall shear and distribution of early atheroma in man. Nature. 1969;223:1159–1160. doi: 10.1038/2231159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Case J. Ingram DA. Haneline LS. Oxidative stress impairs endothelial progenitor cell function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1895–1907. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castier Y. Brandes RP. Leseche G. Tedgui A. Lehoux S. p47phox-Dependent NADPH oxidase regulates flow-induced vascular remodeling. Circ Res. 2005;97:533–540. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000181759.63239.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang K. Weiss D. Suo J. Vega JD. Giddens D. Taylor WR. Jo H. Bone morphogenic protein antagonists are coexpressed with bone morphogenic protein 4 in endothelial cells exposed to unstable flow in vitro in mouse aortas and in human coronary arteries: role of bone morphogenic protein antagonists in inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2007;116:1258–1266. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaqour B. Howard PS. Richards CF. Macarak EJ. Mechanical stretch induces platelet-activating factor receptor gene expression through the NF-kappaB transcription factor. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:1345–1355. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1999.0967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cola C. Almeida M. Li D. Romeo F. Mehta JL. Regulatory role of endothelium in the expression of genes affecting arterial calcification. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:424–427. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cseko C. Bagi Z. Koller A. Biphasic effect of hydrogen peroxide on skeletal muscle arteriolar tone via activation of endothelial and smooth muscle signaling pathways. J Appl Physiol (Bethesda, Md) 2004;97:1130–1137. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00106.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Csiszar A. Ahmad M. Smith KE. Labinskyy N. Gao Q. Kaley G. Edwards JG. Wolin MS. Ungvari Z. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 induces proinflammatory endothelial phenotype. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:629–638. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Csiszar A. Labinskyy N. Jo H. Ballabh P. Ungvari Z. Differential proinflammatory and prooxidant effects of bone morphogenetic protein-4 in coronary and pulmonary arterial endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H569–H577. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00180.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Csiszar A. Labinskyy N. Smith KE. Rivera A. Bakker ETP. Jo H. Gardner J. Orosz Z. Ungvari Z. Downregulation of BMP-4 expression in coronary arterial endothelial cells: role of shear stress and the cAMP/PKA pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:776–782. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000259355.77388.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Csiszar A. Smith KE. Koller A. Kaley G. Edwards JG. Ungvari Z. Regulation of bone morphogenetic protein-2 expression in endothelial cells: role of nuclear factor-kappaB activation by tumor necrosis factor-alpha, H2O2, and high intravascular pressure. Circulation. 2005;111:2364–2372. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000164201.40634.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Csiszar A. Wang M. Lakatta EG. Ungvari ZI. Inflammation and endothelial dysfunction during aging: role of NF-{kappa}B. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:1333–1341. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90470.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Bruyn VH. Nuno DW. Cappelli-Bigazzi M. Dole WP. Lamping KG. Effect of acute hypertension in the coronary circulation: role of mechanical factors and oxygen radicals. J Hypertens. 1994;12:163–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Keulenaer GW. Chappell DC. Ishizaka N. Nerem RM. Alexander RW. Griendling KK. Oscillatory and steady laminar shear stress differentially affect human endothelial redox state: role of a superoxide-producing NADH oxidase. Circ Res. 1998;82:1094–1101. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.10.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deckers MM. van Bezooijen RL. van der Horst G. Hoogendam J. van Der Bent C. Papapoulos SE. Lowik CW. Bone morphogenetic proteins stimulate angiogenesis through osteoblast-derived vascular endothelial growth factor A. Endocrinology. 2002;143:1545–1553. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.4.8719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deng Z. Morse JH. Slager SL. Cuervo N. Moore KJ. Venetos G. Kalachikov S. Cayanis E. Fischer SG. Barst RJ. Hodge SE. Knowles JA. Familial primary pulmonary hypertension (gene PPH1) is caused by mutations in the bone morphogenetic protein receptor-II gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:737–744. doi: 10.1086/303059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dernbach E. Urbich C. Brandes RP. Hofmann WK. Zeiher AM. Dimmeler S. Antioxidative stress-associated genes in circulating progenitor cells: evidence for enhanced resistance against oxidative stress. Blood. 2004;104:3591–3597. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dhore CR. Cleutjens JP. Lutgens E. Cleutjens KB. Geusens PP. Kitslaar PJ. Tordoir JH. Spronk HM. Vermeer C. Daemen MJ. Differential expression of bone matrix regulatory proteins in human atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1998–2003. doi: 10.1161/hq1201.100229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ebrahimian TG. Heymes C. You D. Blanc-Brude O. Mees B. Waeckel L. Duriez M. Vilar J. Brandes RP. Levy BI. Shah AM. Silvestre JS. NADPH oxidase-derived overproduction of reactive oxygen species impairs postischemic neovascularization in mice with type 1 diabetes. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:719–728. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edmunds JW. Mahadevan LC. MAP kinases as structural adaptors and enzymatic activators in transcription complexes. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3715–3723. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Bizri N. Guignabert C. Wang L. Cheng A. Stankunas K. Chang CP. Mishina Y. Rabinovitch M. SM22alpha-targeted deletion of bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A in mice impairs cardiac and vascular development, and influences organogenesis. Development. 2008;135:2981–2991. doi: 10.1242/dev.017863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Bizri N. Wang L. Merklinger SL. Guignabert C. Desai T. Urashima T. Sheikh AY. Knutsen RH. Mecham RP. Mishina Y. Rabinovitch M. Smooth muscle protein 22alpha-mediated patchy deletion of Bmpr1a impairs cardiac contractility but protects against pulmonary vascular remodeling. Circ Res. 2008;102:380–388. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Farzaneh-Far A. Weissberg PL. Proudfoot D. Shanahan CM. Transcriptional regulation of matrix gla protein. Z Kardiol. 2001;90(suppl 3):38–42. doi: 10.1007/s003920170040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng JQ. Xing L. Zhang JH. Zhao M. Horn D. Chan J. Boyce BF. Harris SE. Mundy GR. Chen D. NF-kappaB specifically activates BMP-2 gene expression in growth plate chondrocytes in vivo and in a chondrocyte cell line in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:29130–29135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212296200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukui T. Ishizaka N. Rajagopalan S. Laursen JB. Capers Q. Taylor WR. Harrison DG. de Leon H. Wilcox JN. Griendling KK. p22phox mRNA expression and NADPH oxidase activity are increased in aortas from hypertensive rats. Circ Res. 1997;80:45–51. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghaleh B. Hittinger L. Kim SJ. Kudej RK. Iwase M. Uechi M. Berdeaux A. Bishop SP. Vatner SF. Selective large coronary endothelial dysfunction in conscious dogs with chronic coronary pressure overload. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:H539–H551. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.274.2.H539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griendling KK. Sorescu D. Ushio-Fukai M. NAD(P)H oxidase: role in cardiovascular biology and disease. Circ Res. 2000;86:494–501. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.5.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griethe W. Schmitt R. Jurgensen JS. Bachmann S. Eckardt KU. Schindler R. Bone morphogenic protein-4 expression in vascular lesions of calciphylaxis. J Nephrol. 2003;16:728–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grote K. Flach I. Luchtefeld M. Akin E. Holland SM. Drexler H. Schieffer B. Mechanical stretch enhances mRNA expression and proenzyme release of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) via NAD(P)H oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species. Circ Res. 2003;92:e80–e86. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000077044.60138.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gupte SA. Kaminski PM. Floyd B. Agarwal R. Ali N. Ahmad M. Edwards J. Wolin MS. Cytosolic NADPH may regulate differences in basal Nox oxidase-derived superoxide generation in bovine coronary and pulmonary arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H13–H21. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00629.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanna IR. Hilenski LL. Dikalova A. Taniyama Y. Dikalov S. Lyle A. Quinn MT. Lassegue B. Griendling KK. Functional association of nox1 with p22phox in vascular smooth muscle cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1542–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hansmann G. de Jesus Perez VA. Alastalo TP. Alvira CM. Guignabert C. Bekker JM. Schellong S. Urashima T. Wang L. Morrell NW. Rabinovitch M. An antiproliferative BMP-2/PPARgamma/apoE axis in human and murine SMCs and its role in pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1846–1857. doi: 10.1172/JCI32503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J Gerontol. 1956:298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harrison D. Griendling KK. Landmesser U. Hornig B. Drexler H. Role of oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:7A–11A. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03144-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hassel S. Eichner A. Yakymovych M. Hellman U. Knaus P. Souchelnytskyi S. Proteins associated with type II bone morphogenetic protein receptor (BMPR-II) and identified by two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2004;4:1346–1358. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He T. Peterson TE. Holmuhamedov EL. Terzic A. Caplice NM. Oberley LW. Katusic ZS. Human endothelial progenitor cells tolerate oxidative stress due to intrinsically high expression of manganese superoxide dismutase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:2021–2027. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000142810.27849.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Heinke J. Wehofsits L. Zhou Q. Zoeller C. Baar KM. Helbing T. Laib A. Augustin H. Bode C. Patterson C. Moser M. BMPER is an endothelial cell regulator and controls bone morphogenetic protein-4-dependent angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2008;103:804–812. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helvering LM. Sharp RL. Ou X. Geiser AG. Regulation of the promoters for the human bone morphogenetic protein 2 and 4 genes. Gene. 2000;256:123–138. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hilenski LL. Clempus RE. Quinn MT. Lambeth JD. Griendling KK. Distinct subcellular localizations of Nox1 and Nox4 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:677–683. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000112024.13727.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hishikawa K. Luscher TF. Pulsatile stretch stimulates superoxide production in human aortic endothelial cells. Circulation. 1997;96:3610–3616. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hishikawa K. Oemar BS. Yang Z. Luscher TF. Pulsatile stretch stimulates superoxide production and activates nuclear factor-kappa B in human coronary smooth muscle. Circ Res. 1997;81:797–803. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hruska KA. Mathew S. Saab G. Bone morphogenetic proteins in vascular calcification. Circ Res. 2005;97:105–114. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.00000175571.53833.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hsieh HJ. Cheng CC. Wu ST. Chiu JJ. Wung BS. Wang DL. Increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in endothelial cells by shear flow and involvement of ROS in shear-induced c-fos expression. J Cell Physiol. 1998;175:156–162. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199805)175:2<156::AID-JCP5>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hsieh PC. Kenagy RD. Mulvihill ER. Jeanette JP. Wang X. Chang CM. Yao Z. Ruzzo WL. Justice S. Hudkins KL. Alpers CE. Berceli S. Clowes AW. Bone morphogenetic protein 4: potential regulator of shear stress-induced graft neointimal atrophy. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang A. Sun D. Kaley G. Koller A. Superoxide released to high intra-arteriolar pressure reduces nitric oxide-mediated shear stress- and agonist-induced dilations. Circ Res. 1998;83:960–965. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.9.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang MS. Morony S. Lu J. Zhang Z. Bezouglaia O. Tseng W. Tetradis S. Demer LL. Tintut Y. Atherogenic phospholipids attenuate osteogenic signaling by BMP-2 and parathyroid hormone in osteoblasts. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21237–21243. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701341200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Humbert M. Deng Z. Simonneau G. Barst RJ. Sitbon O. Wolf M. Cuervo N. Moore KJ. Hodge SE. Knowles JA. Morse JH. BMPR2 germline mutations in pulmonary hypertension associated with fenfluramine derivatives. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:518–523. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.01762002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hwang J. Saha A. Boo YC. Sorescu GP. McNally JS. Holland SM. Dikalov S. Giddens DP. Griendling KK. Harrison DG. Jo H. Oscillatory shear stress stimulates endothelial production of O2 from p47phox-based NAD(P)H oxidase leading to monocyte adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:47291–47298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ingram DA. Lien IZ. Mead LE. Estes M. Prater DN. Derr-Yellin E. DiMeglio LA. Haneline LS. In vitro hyperglycemia or a diabetic intrauterine environment reduces neonatal endothelial colony-forming cell numbers and function. Diabetes. 2008;57:724–731. doi: 10.2337/db07-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Inoue S. Orimo A. Hosoi T. Matsuse T. Hashimoto M. Yamada R. Ouchi Y. Orimo H. Muramatsu M. Expression of follistatin, an activin-binding protein, in vascular smooth muscle cells and arteriosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13:1859–1864. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.13.12.1859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jacobson A. Yan C. Gao Q. Rincon-Skinner T. Rivera A. Edwards J. Huang A. Kaley G. Sun D. Aging enhances pressure-induced arterial superoxide formation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H1344–H1350. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00413.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jiang J. Struhl G. Protein kinase A and hedgehog signaling in Drosophila limb development. Cell. 1995;80:563–572. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90510-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jo H. Sipos K. Go YM. Law R. Rong J. McDonald JM. Differential effect of shear stress on extracellular signal-regulated kinase and N-terminal Jun kinase in endothelial cells. Gi2- and Gbeta/gamma-dependent signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1395–1401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jo H. Song H. Mowbray A. Role of NADPH oxidases in disturbed flow- and BMP4- induced inflammation and atherosclerosis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1609–1619. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kami D. Shiojima I. Makino H. Matsumoto K. Takahashi Y. Ishii R. Naito AT. Toyoda M. Saito H. Watanabe M. Komuro I. Umezawa A. Gremlin enhances the determined path to cardiomyogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2407. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Katoh Y. Katoh M. Comparative genomics on BMP4 orthologs. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:581–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kinugawa S. Post H. Kaminski PM. Zhang X. Xu X. Huang H. Recchia FA. Ochoa M. Wolin MS. Kaley G. Hintze TH. Coronary microvascular endothelial stunning after acute pressure overload in the conscious dog is caused by oxidant processes: the role of angiotensin II type 1 receptor and NAD(P)H oxidase. Circulation. 2003;108:2934–2940. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000096488.78151.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Koller A. Signaling pathways of mechanotransduction in arteriolar endothelium and smooth muscle cells in hypertension. Microcirculation. 2002;9:277–294. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Landmesser U. Dikalov S. Price SR. McCann L. Fukai T. Holland SM. Mitch WE. Harrison DG. Oxidation of tetrahydrobiopterin leads to uncoupling of endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase in hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1201–1209. doi: 10.1172/JCI14172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lane KB. Machado RD. Pauciulo MW. Thomson JR. Phillips JA., 3rd Loyd JE. Nichols WC. Trembath RC. Heterozygous germline mutations in BMPR2, encoding a TGF-beta receptor, cause familial primary pulmonary hypertension: the International PPH Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;26:81–84. doi: 10.1038/79226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Langenfeld EM. Langenfeld J. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 stimulates angiogenesis in developing tumors. Mol Cancer Res. 2004;2:141–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Laurindo FR. Pedro Mde A. Barbeiro HV. Pileggi F. Carvalho MH. Augusto O. da Luz PL. Vascular free radical release: ex vivo and in vivo evidence for a flow-dependent endothelial mechanism. Circ Res. 1994;74:700–709. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.4.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lee SD. Shroyer KR. Markham NE. Cool CD. Voelkel NF. Tuder RM. Monoclonal endothelial cell proliferation is present in primary but not secondary pulmonary hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:927–934. doi: 10.1172/JCI1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lehoux S. Redox signalling in vascular responses to shear and stretch. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:269–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lehoux S. Castier Y. Tedgui A. Molecular mechanisms of the vascular responses to haemodynamic forces. J Intern Med. 2006;259:381–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lehoux S. Esposito B. Merval R. Loufrani L. Tedgui A. Pulsatile stretch-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 activation in organ culture of rabbit aorta involves reactive oxygen species. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2366–2372. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.11.2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lehoux S. Tedgui A. Signal transduction of mechanical stresses in the vascular wall. Hypertension. 1998;32:338–345. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.2.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lemarie CA. Esposito B. Tedgui A. Lehoux S. Pressure-induced vascular activation of nuclear factor-kappaB: role in cell survival. Circ Res. 2003;93:207–212. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000086942.13523.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lemarie CA. Tharaux PL. Esposito B. Tedgui A. Lehoux S. Transforming growth factor-alpha mediates nuclear factor kappaB activation in strained arteries. Circ Res. 2006;99:434–441. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237388.89261.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Leschik J. Stefanovic S. Brinon B. Puceat M. Cardiac commitment of primate embryonic stem cells. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1381–1387. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liu Y. Zhao H. Li H. Kalyanaraman B. Nicolosi AC. Gutterman DD. Mitochondrial sources of H2O2 generation play a key role in flow-mediated dilation in human coronary resistance arteries. Circ Res. 2003;93:573–580. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000091261.19387.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Luyten FP. Cunningham NS. Ma S. Muthukumaran N. Hammonds RG. Nevins WB. Woods WI. Reddi AH. Purification and partial amino acid sequence of osteogenin, a protein initiating bone differentiation. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:13377–13380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Machado RD. Pauciulo MW. Thomson JR. Lane KB. Morgan NV. Wheeler L. Phillips JA., 3rd Newman J. Williams D. Galie N. Manes A. McNeil K. Yacoub M. Mikhail G. Rogers P. Corris P. Humbert M. Donnai D. Martensson G. Tranebjaerg L. Loyd JE. Trembath RC. Nichols WC. BMPR2 haploinsufficiency as the inherited molecular mechanism for primary pulmonary hypertension. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:92–102. doi: 10.1086/316947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.McNally JS. Davis ME. Giddens DP. Saha A. Hwang J. Dikalov S. Jo H. Harrison DG. Role of xanthine oxidoreductase and NAD(P)H oxidase in endothelial superoxide production in response to oscillatory shear stress. Am J Physiol. 2003;285:H2290–H2297. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00515.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Meyer CJ. Alenghat FJ. Rim P. Fong JH. Fabry B. Ingber DE. Mechanical control of cyclic AMP signalling and gene transcription through integrins. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:666–668. doi: 10.1038/35023621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mikic B. Van der Meulen MC. Kingsley DM. Carter DR. Mechanical and geometric changes in the growing femora of BMP-5 deficient mice. Bone. 1996;18:601–607. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(96)00073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Miriyala S. Gongora Nieto MC. Mingone C. Smith D. Dikalov S. Harrison DG. Jo H. Bone morphogenic protein-4 induces hypertension in mice: role of noggin, vascular NADPH oxidases, and impaired vasorelaxation. Circulation. 2006;113:2818–2825. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.611822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Miura H. Bosnjak JJ. Ning G. Saito T. Miura M. Gutterman DD. Role for hydrogen peroxide in flow-induced dilation of human coronary arterioles. Circ Res. 2003;92:e31–e40. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000054200.44505.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mohazzab HK. Kaminski PM. Wolin MS. NADH oxidoreductase is a major source of superoxide anion in bovine coronary artery endothelium. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H2568–H2572. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.6.H2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mohler ER., 3rd Gannon F. Reynolds C. Zimmerman R. Keane MG. Kaplan FS. Bone formation and inflammation in cardiac valves. Circulation. 2001;103:1522–1528. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.11.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mollnau H. Wendt M. Szocs K. Lassegue B. Schulz E. Oelze M. Li H. Bodenschatz M. August M. Kleschyov AL. Tsilimingas N. Walter U. Forstermann U. Meinertz T. Griendling K. Munzel T. Effects of angiotensin II infusion on the expression and function of NAD(P)H oxidase and components of nitric oxide/cGMP signaling. Circ Res. 2002;90:58e–e65. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000012569.55432.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Morty RE. Nejman B. Kwapiszewska G. Hecker M. Zakrzewicz A. Kouri FM. Peters DM. Dumitrascu R. Seeger W. Knaus P. Schermuly RT. Eickelberg O. Dysregulated bone morphogenetic protein signaling in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1072–1078. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.141200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Moser M. Binder O. Wu Y. Aitsebaomo J. Ren R. Bode C. Bautch VL. Conlon FL. Patterson C. BMPER, a novel endothelial cell precursor-derived protein, antagonizes bone morphogenetic protein signaling and endothelial cell differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:5664–5679. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.16.5664-5679.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Moser M. Patterson C. Bone morphogenetic proteins and vascular differentiation: BMPing up vasculogenesis. Thromb Haemost. 2005;94:713–718. doi: 10.1160/TH05-05-0312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nomura S. Takano-Yamamoto T. Molecular events caused by mechanical stress in bone. Matrix Biol. 2000;19:91–96. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(00)00050-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nowicki PT. Flavahan S. Hassanain H. Mitra S. Holland S. Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ. Flavahan NA. Redox signaling of the arteriolar myogenic response. Circ Res. 2001;89:114–116. doi: 10.1161/hh1401.094367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Oeckler RA. Kaminski PM. Wolin MS. Stretch enhances contraction of bovine coronary arteries via an NAD(P)H oxidase-mediated activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Circ Res. 2003;92:23–31. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000051860.84509.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Osicka TM. Russo LM. Qiu ML. Brammar GC. Thallas V. Forbes JM. Comper WD. Jerums G. Additive effects of hypertension and diabetes on renal cortical expression of PKC-alpha and -epsilon and alpha-tubulin but not PKC-beta 1 and -beta 2. J Hypertens. 2003;21:2399–2407. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200312000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pan D. Rubin GM. cAMP-dependent protein kinase and hedgehog act antagonistically in regulating decapentaplegic transcription in Drosophila imaginal discs. Cell. 1995;80:543–552. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90508-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Park H. Go YM. Darji R. Choi JW. Lisanti MP. Maland MC. Jo H. Caveolin-1 regulates shear stress-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1285–H1293. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Rabinovitch M. Molecular pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2372–2379. doi: 10.1172/JCI33452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rabinovitch M. Pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension. Annu Rev Pathol. 2007;2:369–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.2.010506.092033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rajagopalan S. Kurz S. Munzel T. Tarpey M. Freeman BA. Griendling KK. Harrison DG. Angiotensin II-mediated hypertension in the rat increases vascular superoxide production via membrane NADH/NADPH oxidase activation: contribution to alterations of vasomotor tone. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1916–1923. doi: 10.1172/JCI118623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Riou S. Mees B. Esposito B. Merval R. Vilar J. Stengel D. Ninio E. van Haperen R. de Crom R. Tedgui A. Lehoux S. High pressure promotes monocyte adhesion to the vascular wall. Circ Res. 2007;100:1226–1233. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000265231.59354.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Rothhammer T. Bataille F. Spruss T. Eissner G. Bosserhoff AK. Functional implication of BMP4 expression on angiogenesis in malignant melanoma. Oncogene. 2007;26:4158–4170. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schneider O. Nau R. Michel U. Comparative analysis of follistatin-, activin beta A- and activin beta B-mRNA steady-state levels in diverse porcine tissues by multiplex S1 nuclease analysis. Eur J Endocrinol/Eur Fed Endocrine Soc. 2000;142:537–544. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1420537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shanahan CM. Cary NR. Metcalfe JC. Weissberg PL. High expression of genes for calcification-regulating proteins in human atherosclerotic plaques. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2393–2402. doi: 10.1172/JCI117246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shao JS. Aly ZA. Lai CF. Cheng SL. Cai J. Huang E. Behrmann A. Towler DA. Vascular Bmp Msx2 Wnt signaling and oxidative stress in arterial calcification. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1117:40–50. doi: 10.1196/annals.1402.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shao JS. Cai J. Towler DA. Molecular mechanisms of vascular calcification: lessons learned from the aorta. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1423–1430. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000220441.42041.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Shin V. Zebboudj AF. Bostrom K. Endothelial cells modulate osteogenesis in calcifying vascular cells. J Vasc Res. 2004;41:193–201. doi: 10.1159/000077394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Smadja DM. Bieche I. Silvestre JS. Germain S. Cornet A. Laurendeau I. Duong-Van-Huyen JP. Emmerich J. Vidaud M. Aiach M. Gaussem P. Bone morphogenetic proteins 2 and 4 are selectively expressed by late outgrowth endothelial progenitor cells and promote neoangiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:2137–2143. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.168815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Somers MJ. Mavromatis K. Galis ZS. Harrison DG. Vascular superoxide production and vasomotor function in hypertension induced by deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt. Circulation. 2000;101:1722–1728. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.14.1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sorescu GP. Song H. Tressel SL. Hwang J. Dikalov S. Smith DA. Boyd NL. Platt MO. Lassegue B. Griendling KK. Jo H. Bone morphogenic protein 4 produced in endothelial cells by oscillatory shear stress induces monocyte adhesion by stimulating reactive oxygen species production from a nox1-based NADPH oxidase. Circ Res. 2004;95:773–779. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000145728.22878.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sorescu GP. Sykes M. Weiss D. Platt MO. Saha A. Hwang J. Boyd N. Boo YC. Vega JD. Taylor WR. Jo H. Bone morphogenic protein 4 produced in endothelial cells by oscillatory shear stress stimulates an inflammatory response. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31128–31135. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sorop O. Spaan JA. Sweeney TE. VanBavel E. Effect of steady versus oscillating flow on porcine coronary arterioles: involvement of NO and superoxide anion. Circ Res. 2003;92:1344–1351. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000078604.47063.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sosnoski DM. Gay CV. Evaluation of bone-derived and marrow-derived vascular endothelial cells by microarray analysis. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:463–472. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sucosky P. Balachandran K. Elhammali A. Jo H. Yoganathan AP. Altered shear stress stimulates upregulation of endothelial VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 in a BMP-4- and TGF-{beta}1-dependent pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;29:254–260. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.176347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sweatt A. Sane DC. Hutson SM. Wallin R. Matrix Gla protein (MGP) and bone morphogenetic protein-2 in aortic calcified lesions of aging rats. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:178–185. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tahira Y. Fukuda N. Endo M. Suzuki R. Ikeda Y. Takagi H. Matsumoto K. Kanmatsuse K. Transforming growth factor-beta expression in cardiovascular organs in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats with the development of hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2002;25:911–918. doi: 10.1291/hypres.25.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tai LK. Okuda M. Abe J. Yan C. Berk BC. Fluid shear stress activates proline-rich tyrosine kinase via reactive oxygen species-dependent pathway. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1790–1796. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000034475.40227.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tardif G. Hum D. Pelletier JP. Boileau C. Ranger P. Martel-Pelletier J. Differential gene expression and regulation of the bone morphogenetic protein antagonists follistatin and gremlin in normal and osteoarthritic human chondrocytes and synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2521–2530. doi: 10.1002/art.20441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ten Dijke P. Goumans MJ. Itoh F. Itoh S. Regulation of cell proliferation by Smad proteins. J Cell Physiol. 2002;191:1–16. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Thomson J. Machado R. Pauciulo M. Morgan N. Yacoub M. Corris P. McNeil K. Loyd J. Nichols W. Trembath R. Familial and sporadic primary pulmonary hypertension is caused by BMPR2 gene mutations resulting in haploinsufficiency of the bone morphogenetic protein type II receptor. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:149. doi: 10.1016/s1053-2498(01)00259-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Thomson JR. Machado RD. Pauciulo MW. Morgan NV. Humbert M. Elliott GC. Ward K. Yacoub M. Mikhail G. Rogers P. Newman J. Wheeler L. Higenbottam T. Gibbs JS. Egan J. Crozier A. Peacock A. Allcock R. Corris P. Loyd JE. Trembath RC. Nichols WC. Sporadic primary pulmonary hypertension is associated with germline mutations of the gene encoding BMPR-II, a receptor member of the TGF-beta family. J Med Genet. 2000;37:741–745. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.10.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Tintut Y. Demer L. Role of osteoprotegerin and its ligands and competing receptors in atherosclerotic calcification. J Invest Med. 2006;54:395–401. doi: 10.2310/6650.2006.06019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ungvari Z. Csiszar A. Edwards JG. Kaminski PM. Wolin MS. Kaley G. Koller A. Increased superoxide production in coronary arteries in hyperhomocysteinemia: role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, NAD(P)H oxidase, and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:418–424. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000061735.85377.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]