Abstract

Tarka and Tarkadectes are Middle Eocene mammals known only from the Rocky Mountains region of North America. Previous work has suggested that they are members of the Plagiomenidae, an extinct family often included in the order Dermoptera. Here we describe a new primate, Tarkops mckennai gen. et sp. nov., from the early Middle Eocene Irdinmanha Formation of Inner Mongolia, China. The new taxon is particularly similar to Tarka and Tarkadectes, but it also displays many features observed in omomyids. A phylogenetic analysis based on a data matrix including 59 taxa and 444 dental characters suggests that Tarkops, Tarka and Tarkadectes form a monophyletic group—the Tarkadectinae—that is nested within the omomyid clade. Within Omomyidae, tarkadectines appear to be closely related to Macrotarsius. Dermoptera, including extant and extinct flying lemurs and plagiomenids, is recognized as a clade nesting within the polyphyletic group of plesiadapiforms, therefore supporting the previous suggestion that the relationship between dermopterans and primates is as close as that between plesiadapiforms and primates. The distribution of tarkadectine primates on both sides of the Pacific Ocean basin suggests that palaeoenvironmental conditions appropriate to sustain primates occurred across a vast expanse of Asia and North America during the Middle Eocene.

Keywords: Tarkops, Tarka, Tarkadectes, primates, Plagiomenidae, Dermoptera

1. Introduction

In terms of the group's diversity and geographical distribution, the Eocene was perhaps the heyday for primate evolution. From the very beginning of the Eocene, primates are documented in Europe, Asia and North America (Russell 1964; Szalay & Delson 1979; Gingerich 1986; Rose 1995; Ni et al. 2004, 2005; Beard 2008). Although non-human primates are currently restricted to relatively warm habitats at low latitude, their Eocene distribution was substantially broader. For example, the dry and barren Gobi desert of Inner and Outer Mongolia ranks among the least suitable modern terrestrial habitats for non-human primates. However, palaeontological expeditions and surveys in this region since the 1920s have discovered tremendously diverse mammalian fossils (Granger & Berkey 1922; Chow & Rozhdestvensky 1960; Zhou & Qi 1978; Qi 1980; Meng & McKenna 1998), including sporadic records of primates. The oldest undoubted primate from this region, Baataromomys ulaanus, was recently described from earliest Eocene strata of Inner Mongolia (Ni et al. 2007). Although it is currently documented by a single isolated tooth, B. ulaanus clearly pertains to a primitive member of the Omomyidae. More recently, Wang (2008) reported three additional primate teeth from younger Eocene strata in Inner Mongolia. These three teeth belong to three different primate taxa (Pseudoloris erenensis and two unnamed species of Eosimias), indicating at least moderate taxonomic diversity among the Eocene primates of this region. Altanius orlovi, from the Early Eocene of Outer Mongolia, is the best-known primate-like mammal from this region (Dashzeveg & McKenna 1977; Gingerich et al. 1991). However, its phylogenetic position with respect to undoubted primates remains unclear (Szalay & Delson 1979; Beard & Wang 1995; Gunnell & Rose 2002).

Here, we describe another new primate from the Middle Eocene of Inner Mongolia. The new taxon resembles Tarka stylifera and Tarkadectes montanensis, two enigmatic mammals from the Rocky Mountains region of North America.

Tarka stylifera is documented by several upper and lower jaw fragments from the Tepee Trail Formation of northwestern Wyoming (McKenna 1990). The associated fauna pertains to the Early Uintan (Ui1) North American Land Mammal Age (NALMA), and palaeomagnetic data from this locality place it within Chron C20R. The geomagnetic polarity time scale recently published by Ogg & Smith (2005) estimates the duration of Chron C20R as 45.3–42.7 Ma. Tarkadectes montanensis is documented by a lower jaw fragment and an upper molar from the upper part of the Coal Creek Member of the Kishenehn Formation of northwestern Montana (McKenna 1990). At the time that T. montanensis was originally described, it was thought to date to the Chadronian NALMA, which was then considered to be Early Oligocene (McKenna 1990). More recent palaeontological and geological work indicates that the type locality of T. montanensis is actually Uintan (Pierce & Constenius 2001), making it comparable in age to T. stylifera.

Tarka and Tarkadectes were originally assigned, along with Ekgmowechashala, to the Plagiomenidae (McKenna 1990). Earlier workers regarded Ekgmowechashala as a late-occurring and morphologically aberrant member of the Omomyidae (MacDonald 1963, 1970; Szalay 1976). Plagiomenids are widely considered to be the sister-group of extant dermopterans (Matthew & Granger 1918; Simpson 1945; Rose 1973, 1975, 1982, 2007; Rose & Simons 1977; Bown & Rose 1979; McKenna & Bell 1997; Bloch et al. 2007). Szalay & Lucas (1996) reaffirmed that Ekgmowechashala is an omomyid primate rather than a plagiomenid dermopteran. They also called into question any special affinity between either Ekgmowechashala and Tarka or Ekgmowechashala and Tarkadectes, and they proposed the new plagiomenid subfamily Tarkadectinae to encompass Tarka and Tarkadectes. Rose (2007) agreed that Tarka and Tarkadectes are closely related and noted that they are remarkably different from other plagiomenids. However, Rose accepted the plagiomenid status of Tarka and Tarkadectes.

In this paper, we describe a new tarkadectine taxon from Inner Mongolia as the first Asian record of this enigmatic group of mammals. By undertaking a phylogenetic analysis including a wide range of euarchontan mammals, our study suggests that tarkadectines are not closely related to plagiomenids. Instead, they are nested within omomyid primates. The new taxon expands the diversity of Eocene primates and provides yet another example of an Eocene primate clade that was able to disperse across the high-latitude Beringian region that connected northeastern Asia with northwestern North America during the Paleogene.

2. Geological background

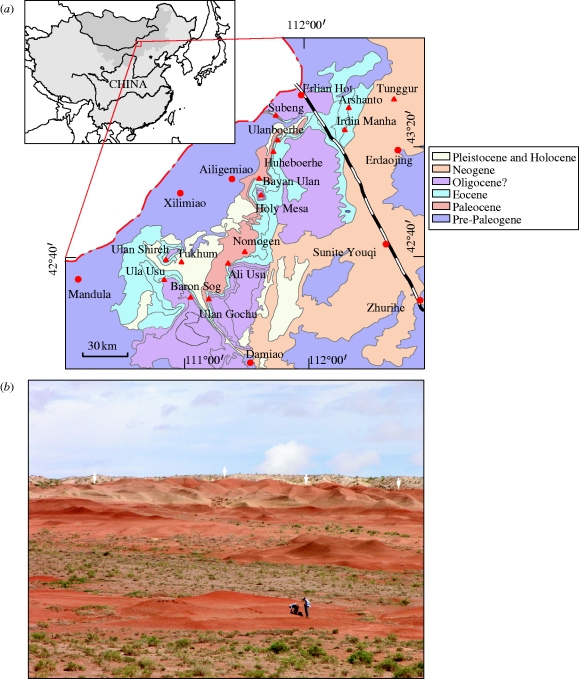

The new tarkadectine specimen was recovered from basal strata of the Irdinmanha Formation at the Huheboerhe locality in the Erlian Basin of Inner Mongolia (figure 1). The Irdinmanha Formation is composed of grey beds, dominated by fluvial sandy clay, sand and gravel, and characterized by numerous channel-cuts and fills (Berkey & Morris 1927; Qi 1980; Meng et al. 2007). At the Huheboerhe locality, the Irdinmanha Formation is approximately 10 m thick. It consists of two units. The upper unit is dominantly greyish white sandy conglomerates, with poorly sorted, poorly rounded, dark-coloured debris. The lower unit contains grey muddy sandstone and coarse sandstone, inter-bedded with lenses of conglomerate and reddish sandy mudstone, and thin-layered yellowish green sandy mudstone and sandstone. Locally, the base of the Irdinmanha Formation contains white nodules and reddish mudstone clasts from underlying beds. The contact between the Irdinmanha Formation and the underlying Arshanto Formation is marked by an erosional unconformity. Both units of the Irdinmanha Formation are fossiliferous. Fossils from the lower unit are particularly abundant, including rodents, lagomorphs, hyaenodontids, artiodactyls, perissodactyls and the new tarkadectine primate.

Figure 1.

(a) Map showing fossil mammal localities in the Erlian region and the outcrop pattern for Cenozoic rocks there. Triangles indicate fossil localities, circles indicate cities or towns. (b) Photo of the Huheboerhe fossil locality. White arrows indicate the contact between the Irdinmanha Formation (above) and the Arshanto Formation (below).

The age of the Irdinmanha Formation is conventionally regarded as Middle Eocene. The mammalian fauna from the Irdinmanha Formation is referred to the Irdinmanhan Asian Land Mammal Age (or ALMA), correlated to the early to middle Middle Eocene (Li & Ting 1983; Russell & Zhai 1987; Tong et al. 1995).

3. Systematic palaeontology

Order Primates Linnaeus 1758

Family Omomyidae Trouessart 1879

Subfamily Tarkadectinae Szalay & Lucas 1996

Type genus: Tarkadectes McKenna 1990.

Included genera: Tarka McKenna 1990; Tarkops gen. nov.

Diagnosis: i1 enlarged and procumbent. i2 very small. Lower canine small and premolariform. p1 absent. p2 absent or very small. p4 trigonid with large paraconid, trenchant paracristid and metaconid similar in height to protoconid. p4 talonid reduced to short distal heel. Buccal cingulid of p4 strong, variably with cingular cusp. Lower molars bunodont, with trigonid slightly higher than talonid. Distal slope of metaconid strongly tilted mesially, sometimes with a step-like metastylid. Buccal cingulid of lower molars very strong, variably with cingular cusps. m3 narrower than m1 and m2. Distal heel of m3 relatively long. P4 and upper molars with wide stylar shelf and large stylar cusps. Paraconule, metaconule and mesostyle of upper molars large. Pre- and postprotocristae fail to reach paraconule and metaconule, respectively.

Tarkops, gen. nov.

Type species: Tarkops mckennai, sp. nov.

Etymology: Allusion to Tarka. The Greek suffix ‘-ops’ means ‘having the appearance of.’

Distribution: Early Middle Eocene, Inner Mongolia, China.

Diagnosis: As for the type species.

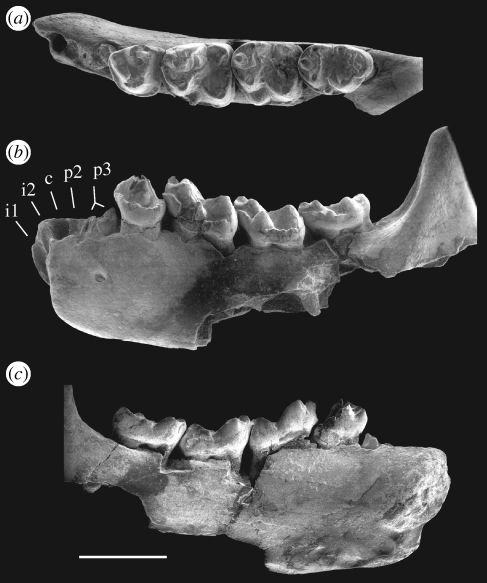

Tarkops mckennai, sp. nov. (figure 2; table 1)

Figure 2.

Holotype specimen of Tarkops mckennai gen. et sp. nov. (IVPP V16424). (a) occlusal view; (b) buccal view; (c) lingual view. Scale bar indicates 5 mm.

Table 1.

Measurements of the teeth of Tarkops mckennai gen. et sp. nov. (mm).

| length | width of trigonid | width of talonid | |

|---|---|---|---|

| p4 | 3.3 | 3.0 | — |

| m1 | 4.5 | 3.3 | 3.8 |

| m2 | 4.2 | 4.0 | 3.6 |

| m3 | 4.4 | 3.0 | 2.8 |

Holotype: IVPP V16424, an incomplete left lower jaw preserving p4–m3 and the roots or alveoli of the anterior teeth.

Etymology: In honour of Dr Malcolm C. McKenna, whose expeditions to the Tepee Trail Formation led to the recovery of T. stylifera and who first described the North American members of the Tarkadectinae.

Type locality and horizon: Huheboerhe, Inner Mongolia, China. Basal strata of the Irdinmanha Formation, early Middle Eocene.

Diagnosis: p4 differs from that of Tarkadectes in having much more reduced talonid. Lower molars differ from those of Tarkadectes in having large cingular cusps buccal to the hypoflexid, and in lacking the centroconid on the cristid obliqua. p4 differs from that of Tarka in having only an incipient cingular cusp. Lower molars differ from those of Tarka in having prominent paraconids near the midline of the trigonid of m2–3, in lacking step-like metasylids on m1–2, and in lacking a cingular cusp buccal to the hypoconid on m1. It further differs from Tarka in retaining a diminutive p2.

Description: T. mckennai is a relatively large omomyid. Its body size can be estimated at 2282 g using regressions of body mass as a function of m1 area (Gingerich 1981). The mandible of the only known specimen is deep relative to the crown height of the molars. The mandibular symphysis is unfused and its long axis is tilted anteriorly, forming an angle of roughly 75 degrees with respect to the tooth row.

The anteriormost alveolus is large and mesially inclined. It is interpreted as the alveolus for the enlarged and procumbent i1. Immediately posterior to the alveolus of i1 is a tiny procumbent alveolus, indicating the presence of a very small i2. Posterior to the alveolus for i2 is a relatively large and nearly vertical alveolus, which is interpreted as the alveolus for c1. The c1 alveolus is substantially larger than the alveoli on either side of it. As in many omomyids, the c1 root in T. mckennai appears to be mesiodistally compressed. As a result, the long axis of the canine alveolus is nearly perpendicular to the mandibular ramus. The alveolus posterior to that for the c1 is as tiny as that of i2. This diminutive alveolus almost certainly supported a vestigial, single-rooted p2. Posterior to the tiny alveolus for p2 and anterior to p4, there are two alveoli with two roots preserved in place. The two roots very closely approximate one another. The orientations of the root canals suggest that they belong to the same tooth, interpreted here as a double-rooted p3. Although the crown of p3 is not preserved, its roots indicate that p3 was about the same size as p4.

In occlusal outline, p4 approximates the shape of a quarter-circle, having a rounded mesiobuccal border and straight lingual and distal borders. The protoconid and metaconid show minor damage on their tips, but their general morphology is not obscured. The protoconid is stout, being only slightly higher than the protoconid of m1. The metaconid is very large, almost as high as the protoconid. In contrast to many omomyids, in which the metaconid is distolingual in position relative to the protoconid, the p4 metaconid of T. mckennai is lingual and slightly mesial to the protoconid. The paraconid of p4 is small and low, mesial to the metaconid. The valley between the paraconid and metaconid is lingually open. No crest is present between these two cusps. By contrast, a strong, trenchant paracristid connects the tips of the protoconid and paraconid. The mesiolingual part of the paracristid is elevated, forming a strong shearing crest. The talonid is reduced to little more than a distal cingulid. The strong buccal cingulid continuously envelops the mesiobuccual and buccal margins of p4. A tiny cingular cusp is present distobuccal to the protoconid.

As is typical for Eocene primates, the molars of T. mckennai are very bunodont. Lower m1 is the largest molar. Its trigonid is slightly higher than the talonid. The protoconid is low and stout. The metaconid is slightly larger than the protoconid and directly lingual to the latter cusp. The paraconid is much smaller than the protoconid and the metaconid. It is mesially positioned relative to the metaconid. The shallow valley between the paraconid and metaconid is lingually opened. The paracristid is long and prominent, but not very elevated. The post-metacristid is also long and prominent, forming the longest shearing crest along the lingual border of the tooth. The protocristid is very weakly developed, yielding a distally open valley between the protoconid and metaconid. The talonid of m1 is wider than the trigonid. The hypoconid is very stout, being the largest cusp of the tooth. The entoconid is as tall as the hypoconid, but much smaller volumetrically. The cristid obliqua is low, and it joins the postvallid below the protoconid. The hypoconulid is absent, allowing the postcristid to connect directly to the entoconid. The talonid basin is broad and shallow, with a crenulated surface. The mesiobuccal and buccal cingulids are very strong. A very characteristic, large cingular cusp occurs distobuccal to the protoconid, occupying much of the hypoflexid.

m2 is almost identical to m1, except that its paraconid is more buccally positioned. m3 is smaller than m1 and m2. Its trigonid is very similar to that of m2, possessing a paraconid that lies close to the midline of the trigonid, between the protoconid and the metaconid. Its talonid is more shallow and flat. The m3 hypoconulid is broad and flat, forming an enlarged distal heel. The length of this distal heel is as long as the talonid proper. The entoconid of m3 is very low and small, nearly being confluent with the distal heel. The mesiobuccal and buccal cingulids of m3 are very strong. The peculiar cingular cusp occupying the hypoflexid is quite prominent, but smaller than those of m1 and m2.

Comparison: T. mckennai is much smaller than T. stylifera, but these two taxa share large cingular cusps on their lower molars, reflecting their close relationship (figure 3). The lower dentition of T. stylifera is fully known, but the homologies of its anterior tooth loci are subject to dispute. Posterior to the enlarged i1 and anterior to p3 in T. stylifera, there are two small teeth, which are similar in size. McKenna (1990) tentatively interpreted these teeth as c1 and p1. Accordingly, McKenna (1990) regarded i2 and p2 as being absent in T. stylifera. In T. mckennai, the size, shape and orientation of the anterior alveoli strongly suggest the presence of i1, i2, c1 and p2 (see above). We therefore regard p1 to be absent in T. mckennai, as is the case in all but the most basal members of the Omomyidae. Bearing in mind this new information from T. mckennai, we believe that the two small teeth between i1 and p3 in T. stylifera should be reinterpreted as i2 and c1. If so, p1 and p2 must have been absent in T. stylifera, leaving a short diastema between c1 and p3. Both T. stylifera and T. mckennai have p4 with a fully developed trigonid coupled with a highly reduced talonid. The p4 of T. stylifera is more derived than that of T. mckennai in having a very large cingular cusp distobuccal to the protoconid. In T. mckennai, p4 bears only an incipient cusp in this location. The molars of both taxa are generally similar: they are all very bunodont; the trigonid is not much higher than the talonid; the metaconid is relatively large; the hypoconid is very stout; the entoconid is low and blunt; the hypoconulid is very small or absent; the talonid basin is broad and shallow with a crenulated surface; and the buccal cingulid is very strong, with enlarged cingular cusps. The obvious differences between these taxa lie in the relatively derived condition of T. stylifera with respect to T. mckennai. The p4–m2 of T. stylifera bear much larger cingular cusps than do their counterparts in T. mckennai. The m1 of T. stylifera not only has a large cingular cusp distobuccal to the protoconid, but it also bears a second cingular cusp buccal to the hypoconid. The paraconids on m2–3 in T. stylifera are much more reduced than those of T. mckennai, being more shelf-like than cuspidate in structure. Finally, m1 and m2 of T. stylifera each bears a large metastylid on the distal slope of the metaconid. No such cusp occurs on m1 and m2 in T. mckennai.

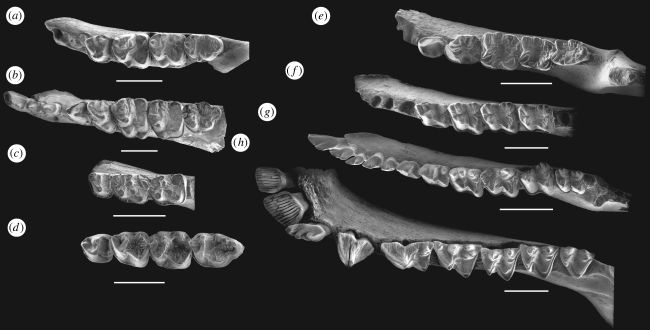

Figure 3.

Lower dentitions of tarkadectines, Macrotarsius, Ekgmowechashala, plagiomenids and flying lemur (all shown in occlusal view). (a) Tarkops mckennai gen. et sp. nov., IVPP V16424; (b) Tarka stylifera, reconstructed based on AMNH 113133, 99594, 95733 and 113871; (c) Tarkadectes montanensis, CM 40818; (d) Macrotarsius siegerti, CM 15122 (reversed), CM 16809, CM 1147 (reversed) and CM 19761 (reversed); (e) Ekgmowechashala philotau SDSM 62104; (f) Ellesmene eureka, NMC 30860 (reversed); (g) Plagiomene multicuspis, PU 14552; (h) Cynocephalus volans AMNH 203254. Rescaled to the same m1 length. Scale bars indicate 5 mm.

The known lower dentition of T. montanensis includes p4–m2 only (figure 3). In contrast to T. stylifera and T. mckennai, the teeth of T. montanensis are less bunodont, with relatively sharp crest and cusps. As is the case in T. mckennai, but in contrast to T. stylifera, p4 of T. montanensis has only an incipient cingular cusp distobuccal to the protoconid. The buccal cingulid of p4 in T. montanensis is much stronger than that of T. mckennai. The p4 talonid in T. montanensis is less reduced than that of T. mckennai, forming a slightly elevated heel-like structure. The distobuccal border of the p4 protoconid in T. montanensis bears a prominent crest. In T. mckennai and T. stylifera, the distobuccal border of p4 is rounded. The lower molars of T. montanensis lack the large cingular cusp that distinguishes these teeth in T. mckennai and T. stylifera. Instead, the lower molars of T. montanensis bear nothing more than an incipient cusp on the very strong buccal cingulid. The lower molar paraconids in T. montanensis are relatively large, thereby resembling the condition in T. mckennai, but differing from T. stylifera. The lower molar talonids of T. montanensis are relatively deeper and have narrower basins than is the case in T. stylifera and T. mckennai. The cristid obliqua on the lower molars of T. montanensis is very strong, and it bears two centroconids, which make the talonid basin appear crowded. In T. mckennai and T. stylifera, the cristid obliqua on the lower molars is low, short and more buccally oriented.

Tarkops mckennai is less derived than T. stylifera and T. montanensis in preserving more generalized characters of omomyid primates. The anterior dentition, including an enlarged and procumbent i1, a small i2, a slightly larger c1 and a very reduced p2, is a common condition among omomyid primates. The p4 and lower molars of T. mckennai share many striking similarities with those of Macrotarsius (figure 3). As in T. mckennai, the trigonid of p4 in Macrotarsius is fully molarized. Its paraconid is large and mesially positioned relative to the even larger metaconid. In contrast to many anaptomorphine omomyids, the metaconid of p4 in Macrotarsius is very high and more mesially positioned, therefore being located directly lingual to the protoconid. Its paracristid forms a high trenchant crest, with a significantly elevated mesiolingual end. In Macrotarsius, the talonid of p4 is also very short, although it is proportionally not as short as that in T. mckennai. The distal border of the p4 talonid in Macrotarsius forms a straight transverse crest that resembles the straight distal cingulid of p4 in T. mckennai. The molars of T. mckennai also share many similarities with those of Macrotarsius, including the presence of a relatively large metaconid, a small paraconid, a narrower trigonid compared with the talonid, and a relatively broad and shallow talonid basin. The peculiar cingular cusps on the lower molars of T. mckennai, Tarka and Tarkadectes are not found in other primates. However, in some omomyids, such as Macrotarsius, Hemiacodon, Ourayia, Ageitodendron and Wyomomys, the buccal cingulids of the lower molars are very strong.

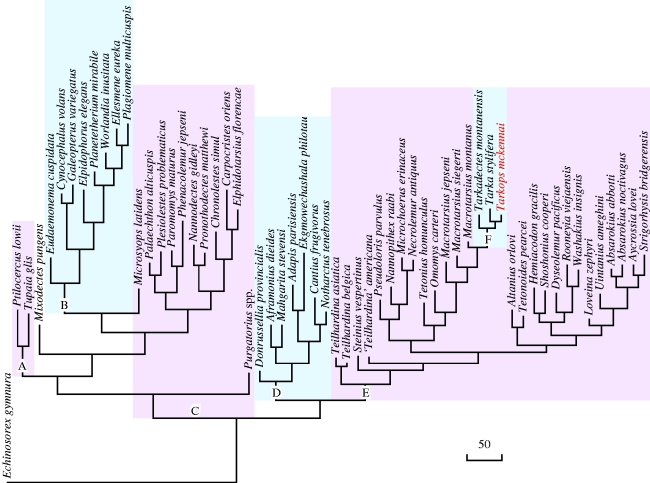

4. Phylogenetic analysis

Our phylogenetic analysis is based on a data matrix (see the electronic supplementary material) including 59 taxa and 444 dental characters. Of the 59 taxa, one insectivoran, Echinosorex gymnura, has been designated as the outgroup. The ingroup comprises two scandentians, one purgatoriid, two paromomyids, two palaechthonids, two plesiadapids, three carpolestids, two dermopterans, one microsyopid, one mixodectid, six plagiomenids and 36 primates. Eighty-eight of the 444 characters are ordered. Three hundred and eighty characters are parsimony-informative. All characters have equal weight. Gaps are treated as ‘missing’, and the multistate taxa interpretation is set to ‘variable’. Heuristic search with random Addition Sequence and Tree-Bisection-Reconnection branch-swapping was performed in PAUP v. 4.0* Beta (Swofford 2002). Ten thousand searches were replicated.

A single most parsimonious tree was found. This tree is 3181 steps long, with a Consistency Index of 0.2760 and a Retention Index of 0.5009.

Our phylogenetic analysis supports the monophyly of the three tarkadectines, T. mckennai, T. stylifera and T. montanensis (figure 4). This clade branches from other omomyids along a stem of 24 character changes. Within the tarkadectine group, T. mckennai and T. stylifera are sister taxa. They share 10 character changes from the common ancestor of the Tarkadectinae. T. mckennai shows eight character changes from the common ancestor of these two taxa, while T. stylifera shows 16 character changes. T. montanensis is the sister taxon of T. mckennai+T. stylifera. There are 18 character changes from the last common ancestor of the Tarkadectinae to T. montanensis.

Figure 4.

Phylogeny of some euarchontans. Background shading indicates the following groups: A, scandentians; B, dermopterans (including extant flying lemurs and plagiomenids); C, polyphyletic group of plesiadapiforms; D, adapiforms; E, omomyids; and F, tarkadectines within Omomyidae. Scale bar indicates 50 character changes.

The tarkadectines are nested well within the omomyid clade. They are particularly close to Macrotarsius. Three species of Macrotarius and tarkadectines form a monophyletic group. This group is well separated from other omomyids by a branch length of 39 character changes.

Tarkadectines were previously considered to be closely related to plagiomenids (McKenna 1990). Our phylogenetic analysis does not support this hypothesis. The six plagiomenids included in our analysis are widely segregated from the primates, and the two extant dermopterans appear to form a clade that is nested within the plagiomenid radiation. This plagiomenid/extant dermopteran clade forms the sister group of Microsyops. Dermopterans and Microsyops then comprise the sister group of a monophyletic group including carpolestids, plesiadapids, palaechthonids and paromomyids.

The assemblage of taxa that is traditionally included in Plesiadapiformes is a polyphyletic group. Purgatorius does not join the other plesiadapiforms, but branches from the base of a clade including scandentians, dermopterans, mixodectids and other plesiadapiforms. Microsyops is actually the sister taxon of dermopterans.

The enigmatic primate Ekgmowechashala joins the adapiforms, as the sister taxon of Adapis. Ekgmowechashala and six other adapiform primates form a monophyletic group.

5. Discussion

McKenna (1990) originally suggested that Tarka and Tarkadectes are closely related to Ekgmowechashala, and that the entire assemblage could be grouped in a subfamily (Ekgmowechashalinae) of Plagiomenidae. Ekgmowechashala was first described as an omomyid primate, although it was always acknowledged that no omomyid actually resembles Ekgmowechashala in detail (MacDonald 1963). Szalay (1976) suggested that the ancestry of Ekgmowechashala was very probably near the genus Rooneyia. Later on, Rose & Rensberger (1983) reported upper teeth assigned to Ekgmowechashala, the structure of which were interpreted to strengthen its possible relationship with Rooneyia. Szalay & Lucas (1996) reasserted the primate status of Ekgmowechashala, disagreeing with McKenna's allocation of this genus to the Plagiomenidae. Most recent researchers have accepted the omomyid affinities of Ekgmowechashala. It should be noted, however, that the double-rooted p2 of Ekgmowechashala has never been observed in omomyids, although this primitive condition does occur in some adapiforms.

Szalay & Lucas (1996) emphasized certain aspects of molar morphology in making their case that tarkadectines are only distantly related to Ekgmowechashala. Specifically, they argued that in Ekgmowechashala the lower molar hypoconulid is displaced buccally towards the hypoconid, while the hypoconulid and entoconid are twinned in plagiomenids. They also thought that in Ekgmowechashala the upper molar hypocone is well developed, resembling that in Washakius and Rooneyia, while Tarka and plagiomenids lack hypocones on their upper molars. Tarkops, Tarka and Tarkadectes actually lack the twinned lower molar hypoconulid and entoconid that characterizes extant dermopterans. Rather, their hypoconulids are very small or absent, and they are located between the hypoconid and entoconid, as in Ekgmowechashala and omomyids. Incidentally, plagiomenids also lack twinned lower molar hypoconulid and entoconid. The lower molar entoconids of plagiomenids bear a small, accessory cusp on their mesial crest. This small cusp and the entoconid may functionally resemble the twinned entoconid and hypoconulid of extant dermopterans, but the structures are obviously not homologous. The true hypoconulid in plagiomenids is quite prominent, being located between the entoconid and hypoconid. The so-called hypocone in Ekgmowechashala is more appropriately identified as a pseudohypocone, because it arises from the ‘Nannopithex’-fold of the protocone, not from the distal cingulum. In Washakius and Rooneyia, the hypocone is developed from the distal cingulum. Although Tarka lacks a hypocone, Tarkadectes bears a large, true hypocone.

The superficial similarity between Ekgmowechashala and tarkadectines lies primarily in the very crenulated enamel of their cheek teeth and the frequent occurrence of neomorphic cuspules in both taxa, but the differences between them are more profound. McKenna (1990) noted that the small lower incisors, relatively large canine and double-rooted p2 in Ekgmowechashala differ substantially from the lower anterior dentition of Tarka. In addition to these important differences, detailed comparisons between Ekgmowechashala and tarkadectines suggest that most, if not all, of the neomorphic cuspules occurring in these taxa are unlikely to be homologous. For example, a large neomorphic cusp lies buccal to the protoconid on p4 of Ekgmowechashala, which resembles the cingular cusp on p4 of Tarka. However, these neomorphic cusps are unlikely to be homologous in Tarka and Ekgmowechashala, because the neomorphic cusp on p4 of Ekgmowechashala arises from the buccal slope of the protoconid, while in Tarka this cusp is developed from the buccal cingulid (figure 3).

The discovery of Tarkops suggests that tarkadectines possess a typical omomyid lower dental formula of i2; c1; p2–3; m3, which is very different from that of plagiomenids (figure 3), which have a lower dental formula of i3; c1; p4; m3 (Rose 1973, 1975, 1982; Bown & Rose 1979; Dawson et al. 1993). The lower incisors of plagiomenids are bi-lobed (Rose 1973, 1975, 1982; Bown & Rose 1979), while the i1 of tarkadectines is enlarged and lanceolate, and the i2 is small and simple in construction. The lower premolars of plagiomenids tend to be progressively molarized distally, so that p3 and p4 typically possess a very well-developed talonid (figure 3). Following a very different evolutionary trend, the lower premolars of tarkadectines are mesiodistally compressed. As a result, p1 is absent and p2 is either greatly reduced (Tarkops) or absent (Tarka), as in many other omomyids (e.g. Szalay 1976; Bown & Rose 1987). The lower molars of plagiomenids have high crowns with trenchant cusps and crests, in contrast to the low-crowned and bunodont molars of tarkadectines and other omomyids (figure 3).

Limited information about the upper molars of Tarka and Tarkadectes has shown some similarities with those of plagiomenids. In both groups, the buccal side of the molars bears a wide stylar shelf and complex stylar cusps. The paraconules and metaconules are enlarged, and relatively isolated. The pre- and postprotocristae do not directly connect the protocone with the paraconule and metaconule, respectively. However, pronounced differences between the upper molars of tarkadectines and plagiomenids are also evident. For example, the stylar cusps in plagiomenids and tarkadectines probably are not entirely homologous. In plagiomenids, the parastyle and metastyle are enlarged and very buccally displaced, forming a distinctive wing-like structure. In Tarka and Tarkadectes, the parastyle and metastyle are much less buccally positioned, as in other omomyids, but in sharp contrast with the condition in plagiomenids. Two additional stylar cusps in Tarka and Tarkadectes, which are called the mesial stylar cusp and the distal stylar cusp here, are present in a different form in plagiomenids. The mesial stylar cusp, which is present in Plagiomene, Ellesmene, Planetetherium and Worlandia but not in Elpidophorus and Eudaemonema, is nearly fused with the relatively smaller and more buccally positioned parastyle, in contrast to the condition in Tarka and Tarkadectes, in which the mesial stylar cusp is more widely separated from the parastyle. The distal stylar cusp is either absent or very small in plagiomenids.

The upper molars of most omomyids lack any significant development of a stylar shelf. However, the upper molars of Macrotarsius (e.g. M. siegerti) are distinctive in having a well-developed stylar shelf, although this structure is not as broad as its counterpart in Tarka and Tarkadectes. Macrotarsius also has a mesiodistally long protocone, relatively large paraconule and metaconule, and lingually extended mesial and distal cingula. These features seem to have been peculiarly exaggerated in Tarka and Tarkadectes. We hypothesize that Macrotarsius approximates the ancestral morphology of tarkadectines.

McKenna's (1990) phylogenetic analysis indicated that Tarka, Tarkadectes and Ekgmowechashala fall within the plagiomenids. However, because his analysis included only Tarka, Tarkadectes, Ekgmowechashala, plagiomenids and mixodectids, it failed to test whether other taxa, such as omomyids, might be even more closely related to Tarka and Tarkadectes. Our phylogenetic analyses are based on a data matrix with much broader taxon sampling. The results fail to support the proposed phylogenetic link between tarkadectines and plagiomenids. Tarkops, Tarka and Tarkadectes form a stable monophyletic group, which nests within the omomyids with Macrotarsius as its sister group. Interestingly, Ekgmowechashala does not join the tarkadectines or other omomyids, but rather is grouped within the adapiform primates. These phylogenetic results strongly support our conclusions drawn from morphological comparisons.

Previous phylogenetic analyses have tended to support the classical hypothesis that plagiomenids are the sister group of extant dermopterans (Gunnell 1989; Bloch et al. 2007). However, the broader relationships among scandentians, modern dermopterans, mixodectids, plesiadapiforms and primates remain debatable. Beard (1990) and Kay et al. (1990) suggested that extant dermorpterans are closely related to certain plesiadapiforms, particularly paromomyids. Gunnell's (1989) analysis indicated that extant dermopterans and plagiomenids form the sister group of a clade containing plesiadapiforms and eurprimates. Bloch et al. (2007) gave a contradictory result by arguing that dermopterans are the sister group of scandentians. Recent molecular data add even more controversies. Some analyses suggest that dermopterans and scandentians are sister groups (Murphy et al. 2001b; Springer et al. 2003), while others propose that dermopterans are the sister group of primates (Janecka et al. 2007). Still others have gone so far as to suggest that dermopterans fall within the primate radiation (Murphy et al. 2001a; Arnason et al. 2002; Schmitz et al. 2002).

Our phylogenetic analyses based on dental characters suggest that extant dermopterans and plagiomenids are nested within a polyphyletic assemblage of plesiadapiforms. This result indicates that the relationship between dermopterans and primates is at least as close as that between plesiadapiforms and primates.

Aside from its phylogenetic significance, the discovery of the peculiar tarkadectine T. mckennai also illuminates biostratigraphic and biogeographic relationships between the Middle Eocene mammal faunas of Asia and North America.

The Irdinmanhan ALMA has been correlated with the Uintan NALMA (Li & Ting 1983; Russell & Zhai 1987; Tong et al. 1995), although considerable disagreement exists regarding the definition of the Uintan (Robinson et al. 2004). Previous intercontinental faunal correlations are not particularly compelling, however, because many of the mammals from the Irdinmanha Formation, especially the tapiroid perissodactyls (Radinsky 1965), seem to have been confined to Asia and probably experienced a long evolutionary history independent of their North American relatives. The discovery of Tarkops from the Irdinmanha Formation indicates that some mammals do show very close ties between Asia and North America during the Middle Eocene. The relatively primitive anatomy of Tarkops suggests that the Irdinmanhan ALMA is probably slightly older than the Ui1 subage (Shoshonian) of the Uintan NALMA, which produced Tarka.

The discovery of Tarkops, the first Asian member of the otherwise North American clade Tarkadectinae, provides further evidence indicating that a wide variety of mammals were able to disperse directly between Asia and North America during the Middle Eocene (Granger & Gregory 1943; Wall 1980; Woodburne & Swisher 1995). Tarkadectines have very specialized dentitions that probably reflect an adaptation to a very specific diet (McKenna 1990). Furthermore, as relatively small-bodied primates, we can infer that tarkadectines were arboreal, because the only living primates that are wholly or partly terrestrial are certain relatively large-bodied catarrhines and lemurs (e.g. Lemur catta), both of which are only distantly related to tarkadectines. At least two other clades of omomyid primates are known to have shown similarly broad distributions on both sides of the Pacific Ocean during the Middle Eocene. These two clades are Macrotarsius, which is known from Jiangsu Province, China, and multiple sites in western North America (Beard et al. 1994) and the Stockia+Asiomomys clade, which is known from Jilin Province, China, and southern California (Beard & Wang 1991). Intriguingly, Macrotarsius appears to be the sister group of Tarkadectinae, suggesting that both members of this larger clade were especially prone to dispersal between Asia and North America.

Modern primates are among the most thermophilic of all living mammals, and the group as a whole is currently restricted to warm and moist regions that occur at relatively low latitude. Primates inhabited a much broader geographical distribution during the Eocene (Szalay & Delson 1979). The discovery of Tarkops demonstrates that tarkadectine omomyids enjoyed a trans-Pacific distribution that encompassed, at least, parts of northeastern Asia and northwestern North America. We interpret the trans-Pacific distributions of Tarkadectinae, Macrotarsius and the Stockia+Asiomomys clade as evidence for the development of continuously forested and at least moderately warm habitats linking Asia and North America during the Middle Eocene. This geographically broad, forested biome presumably included the Beringian region, which was located at high latitude even then. At least three primate clades were able to use the Beringian dispersal corridor during the transient Middle Eocene warming event that occurred around 44 Ma (Zachos et al. 2001).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by research grants from the Chinese National Science Foundation (40532010 to Y.W.; 40672009 and 40872032 to X.N.), the Major Basic Research Projects of MST of China (2006CB806400 to Y.W.), the US National Science Foundation (BCS-0820602 to K.C.B.; BCS-0820485 to D.L.G.; BCS-0820603 and EF-0629811 to J.M.). We thank Mr Xie Shuhua for preparation of the type specimen, Mr Alan Tabrum for making casts, and Ms Li Qian and Messrs. Jin Xun, Sun Chenkai and Bai Bin for assistance with the fieldwork. Thanks to the editors and two anonymous reviewers, whose comments improved this manuscript.

Footnotes

One contribution to a Special Issue ‘Recent advances in Chinese palaeontology’.

References

- Arnason U., et al. 2002Mammalian mitogenomic relationships and the root of the eutherian tree. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 8151–8156doi:10.1073/pnas.102164299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard K. C.1990Gliding behaviour and palaeoecology of the alleged primate family Paromomyidae (Mammalia, Dermoptera). Nature 345, 340–341doi:10.1038/345340a0 [Google Scholar]

- Beard K. C.2008The oldest North American primate and mammalian biogeography during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 3815–3818doi:10.1073/pnas.0710180105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beard K. C., Wang B.-Y.1991Phylogenetic and biogeographic significance of the tarsiiform primate Asiomomys changbaicus from the Eocene of Jilin Province, People's Republic of China. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol 85, 159–166doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330850205 [Google Scholar]

- Beard K. C., Wang J.-W.1995The first Asian plesiadapoids (Mammalia: Primatomorpha). Ann. Carnegie Mus 64, 1–33 [Google Scholar]

- Beard K. C., Qi T., Dawson M. R., Wang B.-Y., Li C.-K.1994A diverse new primate fauna from middle Eocene fissure-fillings in southeastern China. Nature 368, 604–609doi:10.1038/368604a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkey C. P., Morris F. K.Geology of Mongolia: a reconnaissance report based on the investigations of the years 1922–1923. In Natural History of Central Asia 1927New York, NY:American Museum of Natural History [Google Scholar]

- Bloch J. I., Silcox M. T., Boyer D. M., Sargis E. J.2007New Paleocene skeletons and the relationship of plesiadapiforms to crown-clade primates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 1159–1164doi:10.1073/pnas.0610579104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bown T. M., Rose K. D.1979Mimoperadectes, a new marsupial, and Worlandia, a new dermopteran, from the lower part of the Willwood Formation (Early Eocene), Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. Contrib. Mus. Paleontol. Univ. Mich 25, 89–104 [Google Scholar]

- Bown T. M., Rose K. D.1987Patterns of dental evolution in Early Eocene anaptomorphine primates (Omomyidae) from the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. J. Paleontol 61, 1–162 [Google Scholar]

- Chow M., Rozhdestvensky A. K.1960Exploration in Inner Mongolia—a preliminary account of the 1959 field work of the Sino-Soviet paleontological expedition (SSPE). Vertebrata PalAsiatica 4, 1–10 [Google Scholar]

- Dashzeveg D., McKenna M. C.1977Tarsioid primate from the early Tertiary of the Mongolian People's Republic. Acta Palaeont. Pol 22, 119–137 [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M. R., McKenna M. C., Beard K. C., Hutchison J. H.1993An Early Eocene plagiomenid mammal from Ellesmere and Axel Heiberg Islands, Arctic Canada. Kaupia Darmstaedter Beitraege zur Naturgeschichte 3, 179–192 [Google Scholar]

- Gingerich P. D.1981Early Cenozoic Omomyidae and the evolutionary history of Tarsiiform primates. J. Hum. Evol 10, 345–374doi:10.1016/S0047-2484(81)80057-7 [Google Scholar]

- Gingerich P. D.1986Early Eocene Cantius torresi—oldest primate of modern aspect from North America. Nature 319, 319–321doi:10.1038/319319a0 [Google Scholar]

- Gingerich P. D., Dashzeveg D., Russell D. E.1991Dentition and systematic relationships of Altanius orlovi (Mammalia, Primates) from the early Eocene of Mongolia. Geobios 24, 637–646doi:10.1016/0016-6995(91)80029-Y [Google Scholar]

- Granger W., Berkey C. P.1922Discovery of Cretaceous and older Tertiary strata in Mongolia. Am. Mus. Novit 42, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granger W., Gregory W. K.1943A revision of the Mongolian Titanotheres. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist 80, 349–389 [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell G. F.Evolutionary history of Microsyopoidea (Mammalia, Primates) and the relationship between plesiadapiformes and primates. In Papers on Paleontology 1989Ann Arbor, MI:University of Michigan, Museum of Paleontology [Google Scholar]

- Gunnell G. F., Rose K. D.Tarsiiformes: evolutionary history and adaptation. In The primate fossil record Eds Hartwig W. C.2002. pp. 45–82Cambridge, UK:Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Janecka J. E., Miller W., Pringle T. H., Wiens F., Zitzmann A., Helgen K. M., Springer M. S., Murphy W. J.2007Molecular and genomic data identify the closest living relative of primates. Science 318, 792–794doi:10.1126/science.1147555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay R. F., Thorington R. W., Jr, Houde P. W.1990Eocene plesiadapiform shows affinities with flying lemurs not primates. Nat. (London) 345, 342–344doi:10.1038/345342a0 [Google Scholar]

- Li C.-K., Ting S.-Y.1983The Paleogene mammals of China. Bull. Carnegie Mus. Nat. Hist 21, 9–97 [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald J. R.1963The Miocene faunas from the Wounded Knee area of western South Dakota. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist 125, 139–238 [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald J. R.1970Review of the Miocene Wounded Knee faunas of southwestern South Dakota. Bull. Nat. Hist. Mus. Los Angel. Cty Sci 8, 1–82 [Google Scholar]

- Matthew W. D., Granger W.1918A revision of the Lower Eocene Wasatch and Wind River faunas. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist 38, 565–657 [Google Scholar]

- McKenna M. C.1990Plagiomenids (Mammalia: ?Dermoptera) from the Oligocene of Oregon, Montana, and South Dakota, and Middle Eocene of northwestern Wyoming. In Dawn of the age of mammals in the northern part of the Rocky Mountain interior, North America 243 eds Bown T. M., Rose K. D.211–234Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America [Google Scholar]

- McKenna M. C., Bell S. K.Classification of mammals, above the species level 1997New York, NY:Columbia University Press [Google Scholar]

- Meng J., McKenna M. C.1998Faunal turnovers of Palaeogene mammals from the Mongolian Plateau. Nature 394, 364–367doi:10.1038/28603 [Google Scholar]

- Meng J., Wang Y., Ni X., Beard K. C., Sun C., Li Q., Jin X., Bai B.2007New stratigraphic data from the Erlian Basin: implications for the division, correlation, and definition of Paleogene lithological units in Nei Mongol (Inner Mongolia). Am. Mus. Novit 3570, 1–31doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2007)526[1:NSDFTE]2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Murphy W. J., Eizirik E., Johnson W. E., Zhang Y. P., Ryderk O. A., O'Brien S. J.Molecular phylogenetics and the origins of placental mammals. Nature 409, 2001a614–618doi:10.1038/35054550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy W. J., et al. Resolution of the early placental mammal radiation using Bayesian phylogenetics. Science 294, 2001b2348–2351doi:10.1126/science.1067179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni X., Wang Y., Hu Y., Li C.2004A euprimate skull from the early Eocene of China. Nature 427, 65–68doi:10.1038/nature02126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni X., Hu Y., Wang Y., Li C.2005A clue to the Asian origin of euprimates. Anthropol. Sci 113, 3–9doi:10.1537/ase.04S001 [Google Scholar]

- Ni X., Beard K. C., Meng J., Wang Y., Gebo D. L.2007Discovery of the First Early Cenozoic Euprimate (Mammalia) from Inner Monogolia. Am. Mus. Novit 3571, 1–11doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2007)528[1:DOTFEC]2.0.CO;2 [Google Scholar]

- Ogg J. G., Smith A. G.The geomagnetic polarity time scale. In A geologic time scale 2004 EdsGradstein F. M., Ogg J. G., Smith A. G.2005. pp. 63–86Cambridge, UK:Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Pierce H. G., Constenius K. N.2001Late Eocene-Oligocene nonmarine mollusks of the northern Kishenehn Basin, Montana and British Columbia. Ann. Carnegie Mus 70, 1–112 [Google Scholar]

- Qi T.1980Irdin Manha upper Eocene and its mammalian fauna at Huhubolhe cliff in central Inner Mongolia. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 18, 28–32 [Google Scholar]

- Radinsky L. B.1965Early Tertiary Tapiroidea of Asia. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist 129, 181–264 [Google Scholar]

- Robinson P., Gunnell G. F., Walsh S. L., Clyde W. C., Storer J. E., Stucky R. K., Froehlich D. J., Ferrusquia-Villafranca I., McKenna M. C.Wasatchian through Duchesnean biochronology. In Late Cretaceous and Cenozoic mammals of North America. Biostratigraphy and geochronology EdsWoodburne M. O.2004. pp. 106–155New York, NY:Columbia University Press [Google Scholar]

- Rose K. D.1973The mandibular dentition of Plagiomene (Dermoptera, Plagiomenidae). Breviora Mus. Comp. Zool 411, 1–17 [Google Scholar]

- Rose K. D.1975Elpidophorus, the earliest dermopteran (Dermoptera, Plagiomenidae). J. Mammal 56, 676–679doi:10.2307/1379482 [Google Scholar]

- Rose K. D.1982Anterior dentition of the Early Eocene plagiomenid dermopteran Worlandia. J. Mammal 63, 179–183doi:10.2307/1380694 [Google Scholar]

- Rose K. D.1995The earliest primates. Evol. Anthropol 3, 159–173doi:10.1002/evan.1360030505 [Google Scholar]

- Rose K. D.2007Plagiomenidae and Mixodectidae In Evolution of Tertiary mammals of North America: volume 2, small mammals, xenarthrans, and marine mammals eds Janis C. M., Gunnell G. F.198–238Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press [Google Scholar]

- Rose K. D., Rensberger J. M.1983Upper dentition of Ekgmowechashala (Omomyid Pirmate) from the John Day Formation, Oligo-Miocene of Oregon. Folia Primatol 41, 102–111doi:10.1159/000156120 [Google Scholar]

- Rose K. D., Simons E. L.1977Dental function in the Plagiomenidae: origin and relationships of the mammalian order Dermoptera. Contrib. Mus. Paleontol. Univ. Mich 24, 221–236 [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. E.1964Les mammifères Paléocènes d'Europe Mémoires du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle Nouvelle Série C131–324Paris, France: Mémoires du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle [Google Scholar]

- Russell D. E., Zhai R.1987The Paleogene of Asia: mammals and stratigraph. Mémoires du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Série C: Sciences de la Terre521–488Paris, France: Éditions du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz J., Ohme M., Suryobroto B., Zischler H.2002The colugo (Cynocephalus variegatus, Dermoptera): the primates' gliding sister?. Mol. Biol. Evol 19, 2308–2312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson G. G.1945The principles of classification and a classification of mammals. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist 85, 1–350 [Google Scholar]

- Springer M. S., Murphy W. J., Eizirik E., O'Brien S. J.2003Placental mammal diversification and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1056–1061doi:10.1073/pnas.0334222100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swofford D. L.PAUP* Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods) 2002Sunderland, MA:Sinauer Associates [Google Scholar]

- Szalay F. S.1976Systematics of the Omomyidae (Tarsiiformes, Primates): taxonomy, phylogeny, and adaptations. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist 156, 157–450 [Google Scholar]

- Szalay F. S., Delson E.Evolutionary history of the primates 1979London, UK:Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- Szalay F. S., Lucas S. G.1996The postcranial morphology of Paleocene Chriacus and Mixodectes and the phylogenetic relationships of archontan mammals. Bull. NM Mus. Nat. Hist. Sci 7, 1–47 [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y., Zheng S., Qiu Z.1995Cenozoic mammal ages of China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 33, 290–314 [Google Scholar]

- Wall W. P.1980Cranial evidence for a proboscis in Cadurcodon and a review of snout structure in the family-Amynodontidae (Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotoidea). J. Paleontol 54, 968–977 [Google Scholar]

- Wang B.-Y.2008First record of primate fossils from Late Eocene in Eren region, Nei Mongol, China. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 46, 81–89 [Google Scholar]

- Woodburne M. O., Swisher C. C.Land mammal high-resolution geochronology, intercontinental overland dispersals, sea level, climate, and vicariance. In Geochronology, time scales and global stratigraphic correlation Eds Berggren W. A., Kent D. V., Aubry M.-P., Hardenbol J.1995. pp. 335–364Tulsa, OK:SEPM (Society for Sedimentary Geology)Special publication no. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Zachos J., Pagani M., Sloan L., Thomas E., Billups K.2001Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science 292, 686–693doi:10.1126/science.1059412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M., Qi T.1978Late Paleocene mammalian fossils from Siziwang Banner, Inner Mongolia. Vertebrata PalAsiatica 16, 77–85 [Google Scholar]