Abstract

Extremely low-frequency magnetic fields (from DC to 300 Hz) have been shown to affect pain sensitivity in snails, rodents and humans. Here, a functional magnetic resonance imaging study demonstrates how the neuromodulation effect of these magnetic fields influences the processing of acute thermal pain in normal volunteers. Significant interactions were found between pre- and post-exposure activation between the sham and exposed groups for the ipsilateral (right) insula, anterior cingulate and bilateral hippocampus/caudate areas. These results show, for the first time, that the neuromodulation induced by exposure to low-intensity low-frequency magnetic fields can be observed in humans using functional brain imaging and that the detection mechanism for these effects may be different from those used by animals for orientation and navigation. Magnetoreception may be more common than presently thought.

Keywords: fMRI, nociception, magnetic fields, induced currents, bioelectromagnetics

1. Introduction

Current research demonstrates that magnetic fields affect various aspects of animal behaviour. The influence that magnetoreception can have on the orientation and migration of various species has been widely reported (Johnsen & Lohmann 2008; Stapput et al. 2008), and there is also considerable evidence that magnetic fields, in particular low-frequency magnetic fields, influence nociception in animals and humans (Del Seppia et al. 2007). The initial biophysical detection mechanism of magnetoreception remains controversial, but three candidate general mechanisms exist: (i) detection by magnetic dipoles within cells and tissue; (ii) detection of an induced current; and (iii) detection via the different chemical reaction rates when the electron spins of free radicals are affected by a magnetic field. Evidence to date suggests that the effect on animal orientation is mediated by tissue dipoles and/or the free radical mechanism (Johnsen & Lohmann 2008), while the evidence for anti-nociceptive effects may depend on several mechanisms (Thomas et al. 1997; Prato et al. 2000, 2009; Del Seppia et al. 2007). Within the strong static field of a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, 1.5 T) instrument, mechanisms (i) and (iii) are not likely candidates for the explanation of pulsed electromagnetic field effects (see electronic supplementary material for further discussion on interaction mechanisms). Here, we test for the induced current mechanism for magnetoreception in humans using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), wherein we assume that the application of low-frequency time-varying magnetic fields induces currents affecting neural firing in the central nervous system. Though the induced currents are very weak, networks of neurons are more sensitive to weak fields than isolated neurons (Francis et al. 2003).

It has been shown that analgesia can be induced by repeated exposures to a simple sinusoidal magnetic field repeated daily (Kavaliers & Ossenkopp 1993) and by exposure to a pulsed extremely low-frequency magnetic field (PELFMF; from DC to 300 Hz; Thomas et al. 1997). It has been further reported that this pulsed magnetic field can induce analgesia in humans (Shupak et al. 2004; Thomas et al. 2007). Moreover, in humans, the effect is specific to nociception and does not affect thermal sensory thresholds (Shupak et al. 2004), and is effective on both acute and chronic pain (Thomas et al. 2007). The analgesic effect appears to operate via the central nervous system, as suggested by the effectiveness of localized head-only exposures, and reports of pulsed magnetic field exposures affecting electroencephalographic (EEG) measurements (Cook et al. 2005).

Aside from nociception, research into how magnetic fields can affect biological systems is increasingly showing that pulsed magnetic fields can have subtle neuromodulatory effects. Capone et al. (2009) found that a 75 Hz pulsed electromagnetic field altered a transcranial magnetic stimulation measure in human volunteers. Rohan et al. (2004) describes the temporary beneficial effects of exposure to a pulsed MRI gradient MF sequence while patients with bipolar disorder were undergoing an MR spectroscopy examination. The exposure was caused by the switching magnetic field gradients needed to generate the MRI images. This report was seminal as it suggested that the MRI gradients could be used to induce electric currents with neuromodulatory effects, and that magnetoreception in humans was not confounded by exposure to the strong static field from MRI. Hence, we programmed the gradient system of a 1.5 T clinical MRI system to deliver an analgesia-inducing PELFMF and to monitor, using blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD)-fMRI, the effect of that exposure on the neural processing related to pain perception in healthy volunteers.

Functional MRI can determine the localized relative changes in neural activation of regions of the brain based on changes in blood oxygenation and blood flow that occur in response to the altered metabolic demand of activated neurons. Processing of pain involves coordinated activation across many sites in the brain, including the cingulate cortex, the somatosensory areas, the insula and other parts of the limbic system (Apkarian et al. 2005). Neuromodulation is potentially a very important factor in the fMRI signal according to a recent review by Logothetis (2008), and BOLD-fMRI has been used to determine subtle changes in the experience of pain in previous studies (Wager et al. 2004).

2. Methods

Right-handed healthy adult subjects aged 18–60 years were recruited to participate in an fMRI study. Exclusion criteria included claustrophobia, nerve damage to the hand, analgesic use on the day of the study, alcohol use on the day of the study and the inability to lie still for an hour, as well as any other MRI exclusion criteria (e.g. cardiac pacemakers). Subjects were blinded to their condition of sham versus pulsed magnetic field exposure.

Subjects were given acute thermal pain with a Medoc TSA-II (Medoc, Israel). A 1.6 × 1.6 cm Peltier thermode probe was attached to the hypothenar region of the right-hand and heated under computer control (heat stayed on for 21 s, off for 24 s, with 3 s ramps in between). Each subject underwent a test prior to the fMRI to determine their individual pain tolerance. The target temperature was adjusted individually to attain a subjective pain rating of at least 7/10 on a verbal analogue scale (1–10). Subjects were asked to confirm that they could tolerate that level of pain without moving when in the scanner. Actual temperatures varied between 48°C and 51°C, depending on the subject.

After informed consent and thermal pain pre-testing, subjects were placed in the MRI system, told to hold still and keep their eyes closed during the functional imaging, and that they would have a 50–50 chance of receiving a pulsed magnetic field exposure that may have analgesic effects. Single-shot echo-planar BOLD images were acquired (16, 5 mm-thick oblique slices, 64 × 64 resolution, 192 mm field of view, 3 s repetition time, 50 ms echo time). Slices were primarily transversal, inclined when viewed sagittally so that the frontal sinuses were not included in the imaging volume.

Functional MRI images were acquired on a Siemens Avanto 1.5 T MRI while the thermal pain cycled on and off, 10 times for each round of functional imaging. Immediately after each round, the subjects were asked to rate their subjective pain verbally over the intercom. The subjects then had a 15 min ‘rest’ period within the MRI system during which time they were not allowed to move and were exposed to the PELFMF, or a sham condition. Subjects' heads were gently restrained using the adjustable foam pads included with the Siemens Avanto head coil. The functional imaging and pain protocol was then repeated to obtain ‘post-exposure’ data, following which T1-weighted anatomical images were obtained (3D MPRAGE sequence, 1 mm isovoxel resolution, 192 slices, 256 × 256 mm field of view).

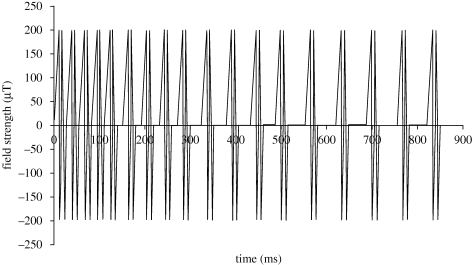

The pulsed magnetic field exposure was done within the MRI system by programming the Z-gradient coils (the gradient along the bore of the magnet). The peak gradient strength was 2 mT m−1, and the patient table was offset 10 cm cranially from the isocentre so that the field at the brow level was set to be 200 µT, the same field strength used in whole-body exposures (non-MRI) within our laboratory in the past with Helmholtz coils (Shupak et al. 2004); see figure 1 for the waveform of the complex pulsed electromagnetic field, and the electronic supplementary information for more detail on the table offset. The peak rate of change of the applied pulsed electromagnetic field (PEMF) was 0.4 T s−1 (with a gradient slew rate of 4 mT m−1 ms−1). The functional imaging portion of the scan used a pulsed gradient waveform with a peak rate of change of magnetic field within the imaging volume of 8 T s−1 (a gradient slew rate of 160 mT m−1 ms−1); see the electronic supplementary material for more details on the waveform of the fMRI sequence.

Figure 1.

PEMF waveform. The PEMF used in this and previous studies. This 853 ms long base pattern was repeated four times with varying delays between each repetition (110, 220, 330, with 1200 ms at the end) for an overall period of 5272 ms. The field strength refers to the field strength at the brow; due to the gradient it would be stronger at the top of the head, weaker towards the bottom.

The PEMF exposure did produce some acoustic noise within the MRI; however, the scanner is a noisy environment, and we were unable to detect the difference in noise levels above background with either a RadioShack sound level meter (model 332055, using an acrylic tube to help direct the sound from the centre of the bore to the meter held safely outside the main field at the foot of the bed) or with a piezoelectric microphone (Bruel & Kjaer type 2801, Denmark); for comparison, the sound of the functional imaging sequence was measured as having 5 times the background sound pressure on the piezoelectric microphone, and an increase of 13 dB on the RadioShack sound level meter. That subjects were not able to determine which condition they were in was confirmed by a χ2-test on their believed condition (p > 0.05).

Functional image processing was performed with Brain Voyager (Brain Innovation BV, The Netherlands) v. 1.9.9. Individual datasets were pre-processed with temporal filtering (with a high-pass filter that had a cut-off frequency of three cycles per scan), three-dimensional motion correction, spatial smoothing (Gaussian 8 mm full-width half maximum), and then spatially normalized to Talairach space to be combined for a general linear model (GLM) group analysis. For the sake of analysis, the ‘pain’ condition was defined to be when the heat was on at target temperature; all other images (baseline and the ramps) were taken to be part of the ‘rest’ condition. Default haemodynamic response curves were used. An average of all Talairach anatomicals was created to display the results of the GLM analysis. The default false discovery rate (FDR) method was used to balance images to q < 0.05. The FDR is an algorithm that accounts for multiple comparisons within fMRI analysis that is less stringent than a Bonferroni correction. All images are presented in the radiological convention (left-is-right).

Based on the initial results seen from the separate group analysis within Brain Voyager and on the a priori knowledge of brain regions associated with pain processing, 1 cm3 cubic regions of interest (ROIs) were chosen and the beta weights exported for analysis in SPSS to explore potential interactions. An α level of p < 0.05 was selected for statistical significance, with no corrections made for testing multiple ROIs (8 total: anterior, dorsal-medial, posterior cingulate; ipsilateral/right and contralateral/left insula and hippocampus/caudate; thalamus).

All the procedures were approved by the University of Western Ontario Human Ethics Review Board (protocol no. 10059).

3. Results

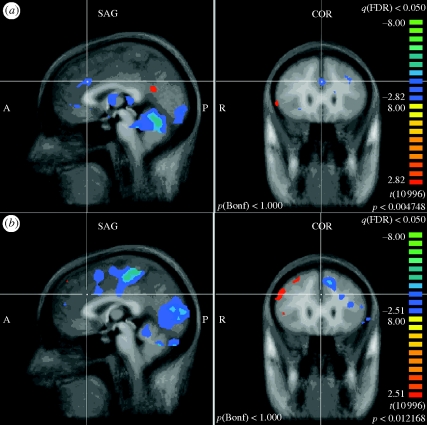

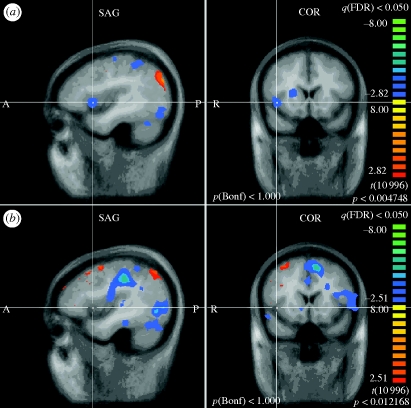

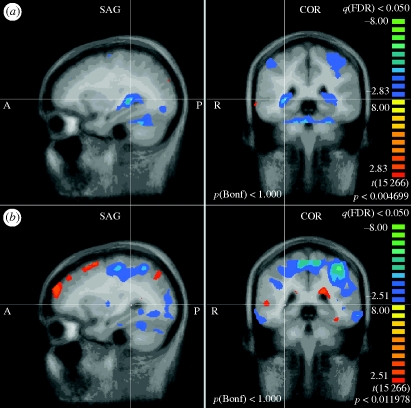

Thirty-one subjects have been included in the analysis (17 sham, 14 PELFMF; see table 1 for summary subject information). Differences were observed within groups over time, as well as between groups in functionally relevant areas: the anterior cingulate, the insula and the hippocampus/caudate (figures 2–4). For each figure, the blue/green false colours indicate that there was less activation in the post-exposure (PELFMF or sham) compared with the pre-exposure fMRI, and the yellow/red colours indicate more activation during the painful stimulus after exposure compared with pre-exposure.

Table 1.

Summary of subject vitals for each group ± s.e.m. The differences in both pre- and post-exposure pain ratings were significant between groups (pre: F(1,29) = 5.2, p < 0.05; post: F(1,29) = 4.9, p < 0.05), but the interaction was not.

| average age | gender | temperature set-point | guessed in sham condition (%) | pre-pain rating | post-pain rating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PELFMF | 32.2 ± 2.7 | 6 F/8 M | 49.6 ± 0.2 | 57 | 8.14 ± 0.2 | 7.57 ± 0.4 |

| sham | 27.6 ± 1.5 | 9 F/8 M | 49.6 ± 0.2 | 71 | 8.79 ± 0.2 | 8.54 ± 0.3 |

Figure 2.

Anterior cingulate. (a) PELFMF post- to pre-condition. This is the statistical difference between the activation seen with pain after exposure minus that seen before. There was a significant decrease in activity after PELFMF exposure compared with before exposure in the anterior cingulate. (b) Sham post- to pre-condition. This image indicates that there was no change in activity within this region in the sham group over time.

Figure 3.

Ipsilateral insula. (a) PELFMF post- to pre-condition. This image shows a significant decrease in activity within the right insula following PELFMF exposure when compared with pre-exposure. (b) Sham post- to pre-condition. No difference is seen due to time alone in the sham condition.

Figure 4.

Hippocampus/caudate. (a) PELFMF post- to pre-condition. This image shows a significant decrease in activity within the hippocampus/caudate area following PELFMF exposure when compared with pre-exposure. Due to the relatively poor spatial resolution, it is difficult to say exactly from which structure(s) this activity is originating. (b) Sham post- to pre-condition. No difference is seen due to time alone in the sham condition.

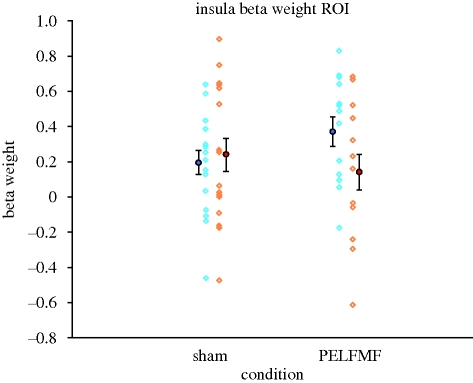

Guided by these visual results, the data from 1 cm3 volumes were extracted and analysed within SPSS to obtain a full model. Significant interactions were found for the anterior cingulate, ipsilateral (right) insula, and the bilateral hippocampus/caudate region (see table 2 for details). The analysed beta weights (a measure of the strength of the correlation between the BOLD signal measured and the pain on/off predictor) are plotted in figure 5 to demonstrate that the interaction is due to a decrease in activity following the 200 µT pulsed magnetic field exposure. See the electronic supplementary material for additional information about the main effects of time as well as event-related average BOLD signal time courses.

Table 2.

Summary of significant interactions found.

| region | interaction F | interaction p | partial η2 | observed power |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| anterior cingulate | F(1,29) = 6.834 | <0.05 | 0.19 | 0.72 |

| insula (ipsilateral) | F(1,29) = 5.204 | <0.05 | 0.15 | 0.60 |

| hippocampus/caudate (ipsilateral) | F(1,29) = 13.803 | <0.01 | 0.32 | 0.94 |

| hippocampus/caudate (contralateral) | F(1,29) = 6.055 | <0.05 | 0.17 | 0.66 |

Figure 5.

Beta weights from ipsilateral insula. The means before (large blue circle) and after (large red circle) sham or pulsed magnetic field exposure (PELFMF) are plotted, with error bars as ±s.e.m. There is a relative decrease following PELFMF exposure, giving rise to a significant interaction. Individual beta scores are plotted as faint open symbols for pre- (blue) and post-exposure (orange) to demonstrate the range of individual variability. The other interactions found likewise appear to be driven largely by a decrease in the activity following PELFMF exposure.

4. Discussion

The anterior cingulate, insula and hippocampus/caudate are classically associated with the integration of the affective components of pain, and a decrease in activation here corresponds well with our hypothesis that this PELFMF influences pain processing in central structures. Functional changes were largely detected only in central structures, which could have been anticipated by the previous work indicating that pain, but not sensory thresholds were affected (Shupak et al. 2004). Some changes in the somatosensory areas were observed over time, but there was no significant interaction with magnetic field exposure.

These fMRI effects were seen after a 15-min exposure, consistent with effects seen in humans on EEG from similar length exposures (Cook et al. 2005) and anti-nociception seen in snails and rodents also after 15-min exposures (Thomas et al. 1997). However, in previous human studies investigating subjective relief from both acute and chronic pain, longer periods of exposure were used (Shupak et al. 2004; Thomas et al. 2007). Here, the short 15-min exposure did not lead to subjective effectiveness, yet the pulsed magnetic field exposure did induce significant changes in functional activity. It is possible that the effect of the PELFMF on nociception is altered by the interactions of the strong static field (1.5 T; Laszlo & Gyires 2009) and the time-varying fields associated with the imaging procedures (Prato et al. 1992).

It is interesting to note that neuromodulation occurred in the environment of the MRI. The effects of the 1.5 T static magnetic field should have interfered with any free radical mechanism. The torque on iron particles such as magnetite produced by the ELFMF would have been very small compared with the torque produced by the 1.5 T static field of the MRI main magnet. There were no subjective changes in pain ratings, but the ELFMF produced during the fMRI procedure could have induced an increase in pain sensitivity countering the analgesic effect as has been previously reported (Prato et al. 1987, 1992). Hence the hypothesis that the effect is produced by induced currents is supported and suggests that the induction of analgesia, at least in humans, may depend on a different mechanism from that for animal orientation and homing. This is not surprising given current evidence that magnetoreception even in birds may be achieved by more than one mechanism with one dependent on light exposure (free radical mechanism) and one independent of light exposure (magnetite; Johnsen & Lohmann 2008; Stapput et al. 2008). Even within the induced current paradigm, different pulse designs may differentially influence behaviour (Thomas et al. 1997). Using the gradient fields to produce a biological effect may become an important technique in the future, particularly if a ‘magnetic contrast’ can be developed, such as a pulsed magnetic field that differentially affects fMRI processing between healthy and patient populations for a certain disease/disorder.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Derek Mitchell, Dr Dwight Moulin, Dr Alexandre Legros, Dr Keith St Lawrence and Mr Lynn Keenliside for their assistance with this project. This project was funded by a grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

References

- Apkarian A. V., Bushnell M. C., Treede R. D., Zubieta J. K. 2005. Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur. J. Pain 9, 463–484. ( 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.11.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capone F., et al. 2009. Does exposure to extremely low frequency magnetic fields produce functional changes in human brain? J. Neural Transm. 116, 257–265. ( 10.1007/s00702-009-0184-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook C. M., Thomas A. W., Keenliside L. D., Prato F. S. 2005. Resting EEG effects during exposure to a pulsed ELF magnetic field. Bioelectromagnetics 26, 367–376. ( 10.1002/bem.20113) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Seppia C., Ghione S., Luschi P., Ossenkopp K. P., Choleris E., Kavaliers M. 2007. Pain perception and electromagnetic fields. Neurosci. Biol. Rev. 31, 619–642. ( 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.01.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis J. T., Gluckman B. J., Schiff S. J. 2003. Sensitivity of neurons to weak electric fields. J. Neurosci. 23, 7255–7261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen S., Lohmann K. J. 2008. Magnetoreception in animals. Phys. Today 61, 29–35. ( 10.1063/1.2897947) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kavaliers M., Ossenkopp K. P. 1993. Repeated naloxone treatments and exposures to weak 60 Hz magnetic fields have ‘analgesic’ effects in snails. Brain Res. 620, 159–162. ( 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90285-U) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo J., Gyires K. 2009. 3 T homogeneous static magnetic field of a clinical MR significantly inhibits pain in mice. Life Sci. 84, 12–17. ( 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.10.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis N. K. 2008. What we can do and what we cannot do with fMRI. Nature 453, 869–878. ( 10.1038/nature06976) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prato F. S., Ossenkopp K. P., Kavaliers M., Sestini E., Teskey G. C. 1987. Attenuation of morphine-induced analgesia in mice by exposure to magnetic resonance imaging: separate effects of the static, radiofrequency and time-varying magnetic fields. Magn. Reson. Imaging 5, 9–14. ( 10.1016/0730-725X(87)90478-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prato F. S., Kavaliers M., Ossenkopp K. P., Carson J. J., Drost D. J., Frappier J. R. 1992. Extremely low frequency magnetic field exposure from MRI/MRS procedures. Implications for patients (acute exposures) and operational personnel (chronic exposures). Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 649, 44–58. ( 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb49595.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prato F. S., Kavaliers M., Thomas A. W. 2000. Extremely low frequency magnetic fields can either increase or decrease analgaesia in the land snail depending on field and light conditions. Bioelectromagnetics 21, 287–301. ( 10.1002/(SICI)1521-186X(200005)21:4%3C287::AID-BEM5%3E3.0.CO;2-N) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prato F. S., Desjardins-Holmes D., Keenliside L. D., McKay J. C., Robertson J. A., Thomas A. W. 2009. Light alters nociceptive effects of magnetic field shielding in mice: intensity and wavelength considerations. J. R. Soc. Interface 6, 17–28. ( 10.1098/rsif.2008.0156) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohan M., Parow A., Stoll A. L., Demopulos C., Friedman S., Dager S., Hennen J., Cohen B. M., Renshaw P. F. 2004. Low-field magnetic stimulation in bipolar depression using an MRI-based stimulator. Am. J. Psych. 161, 93–98. ( 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.93) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shupak N. M., Prato F. S., Thomas A. W. 2004. Human exposure to a specific pulsed magnetic field: effects on thermal sensory and pain thresholds. Neurosci. Lett. 363, 157–162. ( 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.03.069) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stapput K., Thalau P., Wiltschko R., Wiltschko W. 2008. Orientation of birds in total darkness. Curr. Biol. 18, 602–606. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.046) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A. W., Kavaliers M., Prato F. S., Ossenkopp K. P. 1997. Antinociceptive effects of a pulsed magnetic field in the land snail, Cepaea nemoralis. Neurosci. Lett. 222, 107–110. ( 10.1016/S0304-3940(97)13359-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A. W., Graham K., Prato F. S., McKay J., Forster P. M., Moulin D. E., Chari S. 2007. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial using a low-frequency magnetic field in the treatment of musculoskeletal chronic pain. Pain Res. Manage. 12, 249–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager T. D., Rilling J. K., Smith E. E., Sokolik A., Casey K. L., Davidson R. J., Kosslyn S. M., Rose R. M., Cohen J. D. 2004. Placebo-induced changes in fMRI in the anticipation and experience of pain. Science 303, 1162–1167. ( 10.1126/science.1093065) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]