Abstract

Integrins mediate cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix and transmit signals within the cell that stimulate cell spreading, retraction, migration, and proliferation. The mechanism of integrin outside-in signaling has been unclear. We found that the heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein), Gα13, directly bound to the integrin β3 cytoplasmic domain, and that Gα13-integrin interaction was promoted by ligand binding to the integrin αIIbβ3 and by guanosine triphosphate (GTP)-loading of Gα13. Interference of Gα13 expression or a myristoylated fragment of Gα13 that inhibited interaction of αIIbβ3 with Gα13 diminished activation of protein kinase c-Src and stimulated the small GTPase RhoA, consequently inhibiting cell spreading and accelerating cell retraction. We conclude that integrins are non-canonical Gα13-coupled receptors that provide a mechanism for dynamic regulation of RhoA.

Integrins mediate cell adhesion and transmit signals within the cell that lead to cell spreading, retraction, migration, and proliferation (1). Thus, integrins have pivotal roles in biological processes such as development, immunity, cancer, wound healing, hemostasis and thrombosis. The platelet integrin, αIIbβ3, typically displays bidirectional signaling function (2, 3). Signals from within the cell activate binding of αIIbβ3 to extracellular ligands, which in turn triggers signaling within the cell initiated by the occupied receptor (so-called “outside-in” signaling). A major early consequence of integrin “outside-in” signaling is cell spreading, which requires activation of the protein kinase c-Src and c-Src-mediated inhibition of the small guanosine triphosphatase (GTPase) RhoA (4-7). Subsequent cleavage of the c-Src binding site in β3 by calpain allows activation of RhoA, which stimulates cell retraction (7, 8). The molecular mechanism coupling ligand-bound αIIbβ3 to these signaling events has been unclear.

Heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding proteins (G proteins) consist of Gα, Gβ and Gγ subunits (9). G proteins bind to the intracellular side of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) and transmit signals that are important in many intracellular events (9-11). Gα13, when activated by GPCRs, interacts with Rho guanine-nucleotide exchange factors (RhoGEF) and thus activates RhoA (11-14), facilitating contractility and rounding of discoid platelets (shape change). To determine whether Gα13 functions in signaling from ligand-occupied integrin, we investigated whether inhibition of Gα13 expression with small interfering RNA (siRNA) affected αIIbβ3-dependent spreading of platelets on fibrinogen, which is an integrin ligand. We isolated mouse bone marrow stem cells and transfected them with lentivirus encoding Gα13 siRNA. The transfected stem cells were transplanted into irradiated C57/BL6 mice (15). Four to six weeks after transplantation, nearly all platelets isolated from recipient mice were derived from transplanted stem cells as indicated by the enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) encoded in lentivirus vector (Fig. S1, Fig. 1A). Platelets from Gα13 siRNA-transfected stem cell recipient mice showed >80% decrease in Gα13 expression (Fig. 1B). When platelets were allowed to adhere to immobilized fibrinogen [αIIbβ3 binding to immobilized fibrinogen does not require prior “inside-out” signaling activation (16)], platelets depleted of Gα13 spread poorly as compared with control platelets (Fig. 1A, Fig. S2). The inhibitory effect of Gα13 deficiency is unlikely to be caused by its effect on GPCR-stimulated Gα13 signaling because (i) washed resting platelets were used and no GPCR agonists were added, and (ii) prior treatment with 1 mM aspirin [which abolishes thromboxane A2 (TXA2) generation (17)] did not affect platelet spreading on fibrinogen (Fig. S2), making it unlikely the endogenous TXA2-mediated stimulation of Gα13. Furthermore, Gα13 siRNA inhibited spreading of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells expressing human αIIbβ3 (123 cells) (18), which was rescued by an siRNA-resistant Gα13 (Fig. S3). Thus, Gα13 appears to be important in integrin “outside-in” signaling leading to cell spreading.

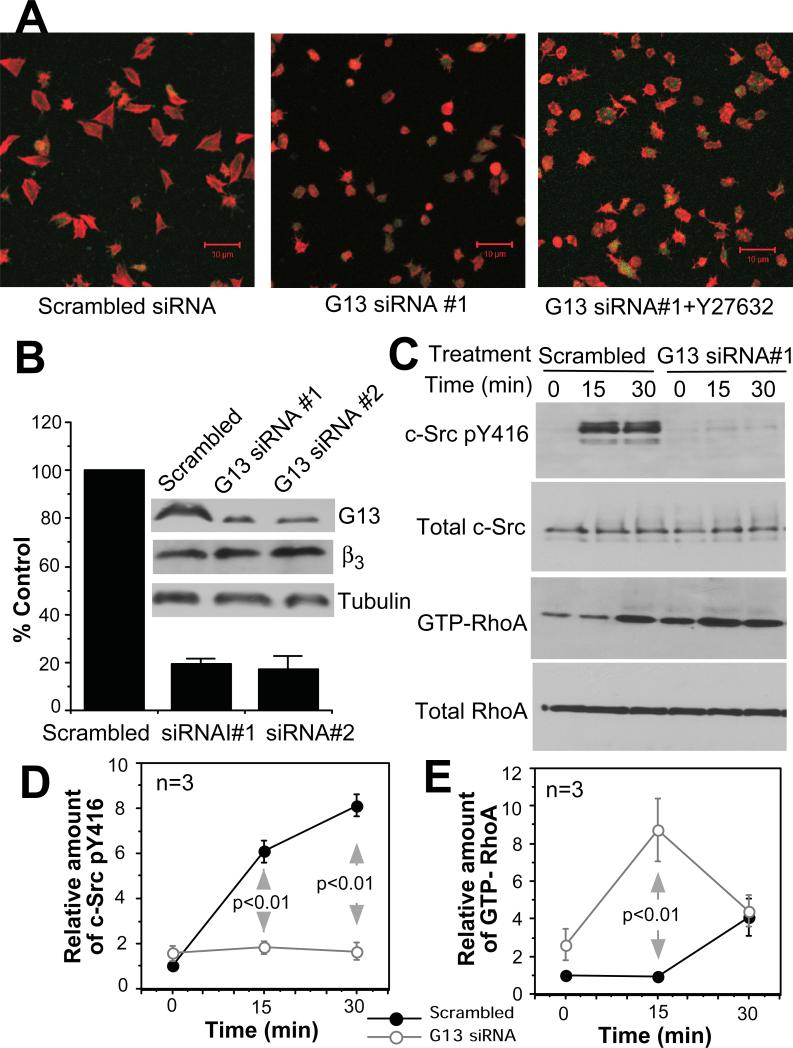

Fig. 1. The role of Gα13 in integrin outside-in signaling.

(A) Confocal microscopy images of spreading scrambled siRNA control platelets or Gα13-depleted platelets (Gα13-siRNA) on fibrinogen, without or with Y27632. Merged EGFP (green) fluorescence and Alex Fluor 546-conjugated phalloidin (Red) fluorescence. (B) Western blot comparison of Gα13 abundance in platelets from mice innoculated with control siRNA- or Gα13-siRNA-transfected bone marrow stem cells. (C, D, E) Mouse platelets from scrambled siRNA- or Gα13 siRNA-transfected stem cells were allowed to adhere to immobilized fibrinogen, solubilized and analyzed for c-Src Tyr416 phosphorylation and RhoA activation.

To determine whether Gα13 serves as an early signaling mechanism that mediates integrin-induced activation of c-Src, we measured phosphorylation of c-Src at Tyr416 (which indicates activation of c-Src) in control and fibrinogen-bound cells. Depletion of Gα13 in mouse platelets or 123 cells abolished phosphorylation of c-Src Tyr416 (Fig. 1C, Fig. S3), indicating that Gα13 may link integrin αIIbβ3 and c-Src activation. Because c-Src inhibits RhoA (7, 19), we also tested the role of Gα13 in regulating activation of RhoA. RhoA activity was suppressed to baseline 15 minutes after platelet adhesion, and became activated at 30 minutes (Fig. 1C), which is consistent with transient inhibition of RhoA by c-Src (7). The integrin-dependent delayed activation of RhoA was not inhibited by depletion of Gα13, indicating its independence of the GPCR-Gα13-RhoGEF pathway (Fig. 1C). In contrast, depletion of Gα13 accelerated RhoA activation (Fig. 1C). Thus, Gα13 appears to mediate inhibition of RhoA. The inhibitory effect of Gα13 depletion on platelet spreading was reversed by Rho-kinase inhibitor Y27632 (Fig. 1A), suggesting that Gα13-mediated inhibition of RhoA is important in stimulating platelet spreading. These data are consistent with Gα13 mediating integrin “outside-in signaling” inducing c-Src activation, RhoA inhibition, and cell spreading.

The integrin αIIbβ3 was co-immunoprecipitated by anti-Gα13 antibody, but not control IgG, from platelet lysates (Fig. 2A). Conversely, an antibody to β3 immunoprecipitated Gα13 with β3 (Fig. 2B). Co-immunoprecipitation of β3 with Gα13 was enhanced by GTP-γS or AlF4- (Fig. 2A, Fig. S4). Thus, β3 is present in a complex with Gα13, preferably the active GTP-bound Gα13. To determine whether Gα13 directly binds to the integrin cytoplasmic domain, we incubated purified recombinant Gα13 (20) with agarose beads conjugated with glutathione S-transferase (GST), or a GST-β3 cytoplasmic domain fusion protein (GST-β3CD). Purified Gα13 bound to GST-β3CD, but not to GST (Fig. 2C). Purified Gα13 also bound to the β1 integrin cytoplasmic domain fused with GST (GST-β1CD) (Fig. 2D). The binding of Gα13 to GST-β3CD and GST-β1CD was detected with GDP-loaded Gα13, but enhanced by GTP-γS and AlF4- (Fig. 2C, 2D), indicating that the cytoplasmic domains of β3 and β1 can directly interact with Gα13, and GTP enhances the interaction. The Gα13-β3 interaction was enhanced in platelets adherent to fibrinogen, and by thrombin, which stimulates GTP binding to Gα13 via GPCR (Fig. 2E). Hence, the interaction is regulated by both integrin occupancy and GPCR signaling.

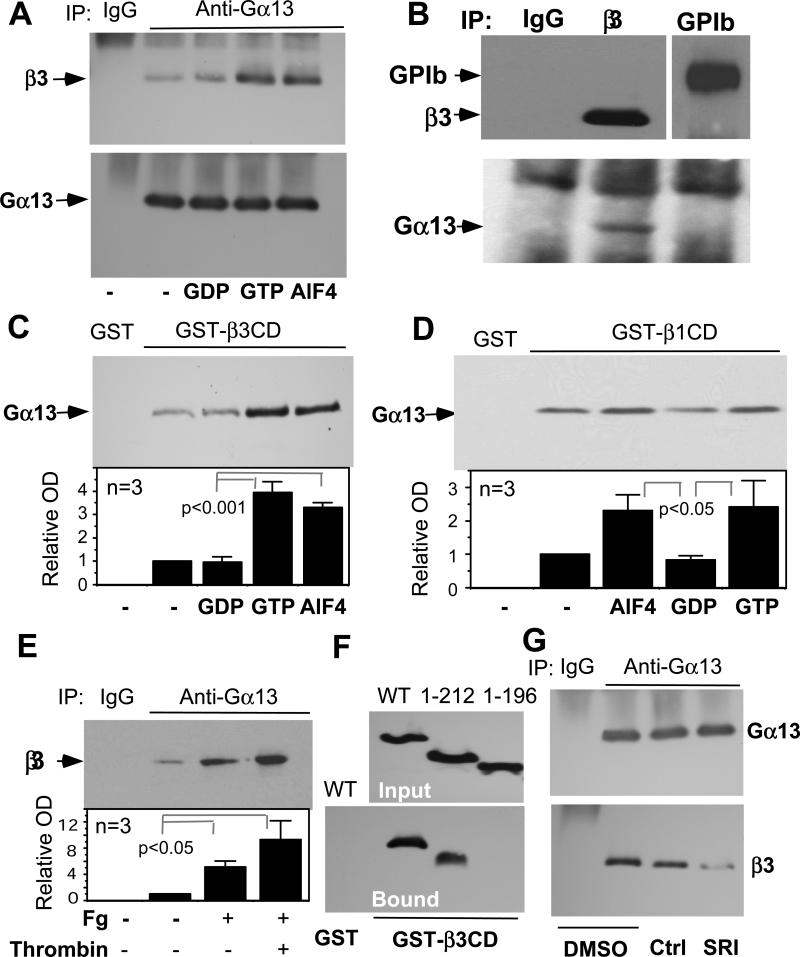

Fig. 2. Binding of Gα13 to β3 and the inhibitory effect of mSRI peptide.

(A) Proteins from platelet lysates were immunoprecipitated with control IgG or antibody to Gα13 with or without 1 μM GDP, 1 μM GTP or 30 μM AlF4-. Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Gα13 or anti-β3 (MAb15). See Fig. S4 for quantitation. (B) Proteins from platelet lysates were immunoprecipitated with control mouse IgG, anti-αIIbβ3 (D57 (24)) or an antibody to the glycoprotein Ibα (GPIb). Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Gα13, anti-β3, or anti-GPIb antibodies. (C, D) Purified GST-β3CD (C) or GST-β1CD (D) bound to glutathione beads was mixed with purified Gα13 with or without 1 μM GDP, 1 μM GTPγS or 30 μM AlF4-. Bound proteins were immunoblotted with anti-Gα13. Quantitative data are shown as mean±SD and p value (t-test). (E) Lysates of control platelets or platelets adherent to fibrinogen in the absence or presence of 0.025 U/ml thrombin were immunoprecipitated with anti-Gα13, and then immunoblotted with MAb15. Quantitative data are shown as mean±SD and p value (t-test). (F) Lysates from 293FT cells transfected with Flag-tagged wild type Gα13 or indicated truncation mutants (see Fig. S5) were precipitated with GST-β3CD- or GST-bound glutathione beads. Bead-bound proteins were immunoblotted with anti-Flag (Bound). Flag-tagged protein amounts in lysates are shown by anti-Flag immunoblot (Input). (G) Protein from platelet lysates treated with 0.1% DMSO, 250 μM scrambled control peptide (Ctrl) or mSRI were immunoprecipitated with anti-Gα13. Immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with anti-Gα13 or anti-β3. See Fig. S4 for quantitation.

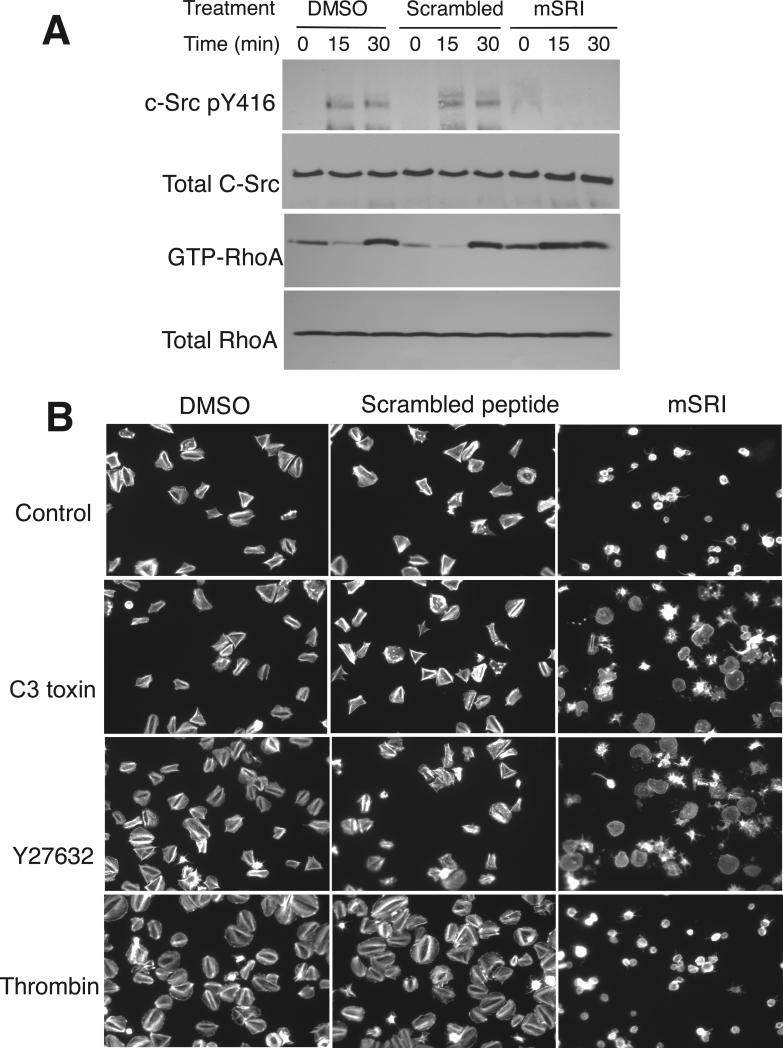

To map the β3 binding site in Gα13, we incubated cell lysates containing Flag-tagged wild type or truncation mutants of Gα13 (Fig. S5) with GST-β3CD beads. GST-β3CD associated with wild type Gα13 and the Gα13 1-212 fragment containing α helical region and switch region I (SRI), but not with the Gα13 fragment containing residues 1-196 lacking SRI (Fig. 2F). Thus, SRI appears to be critical for β3 binding. To further determine the importance of SRI, Gα13-β3 binding was assessed in the presence of a myristoylated synthetic peptide, Myr-LLARRPTKGIHEY (mSRI), corresponding to the SRI sequence of Gα13 (197-209) (21). The mSRI peptide, but not a myristoylated scrambled peptide, inhibited Gα13 binding to β3 (Fig. 2G), indicating that mSRI is an effective inhibitor of β3-Gα13 interaction. Therefore, we further examined whether mSRI might inhibit integrin signaling. Treatment of platelets with mSRI inhibited integrin-dependent phosphorylation of c-Src Tyr416 and accelerated RhoA activation (Fig. 3A). The effect of mSRI is unlikely to result from its inhibitory effect on the binding of RhoGEFs to Gα13 SRI because Gα13 binding to RhoGEFs stimulates RhoA activation, which should be inhibited rather than promoted by mSRI (21). Thus, these data suggest that β3-Gα13 interaction mediates activation of c-Src and inhibition of RhoA. Furthermore, mSRI inhibited integrin-mediated platelet spreading (Fig. 3B), and this inhibitory effect was reversed by C3 toxin (which catalyzes the ADP ribosylation of RhoA) or Y27632, confirming the importance of Gα13-dependent inhibition of RhoA in platelet spreading. Thrombin promotes platelet spreading, which requires cdc42/Rac pathways (22). However, thrombin-promoted platelet spreading was also abolished by mSRI (Fig. 3B), indicating the importance of Gα13-β3 interaction. Thus, Gα13-integrin interaction appears to be a mechanism that mediates integrin signaling to c-Src and RhoA, thus regulating cell spreading.

Fig. 3. Effects of mSRI on integrin-induced c-Src phosphorylation, RhoA activity and platelet spreading.

(A) Washed human platelets pre-treated with DMSO, mSRI, or scrambled control peptide were allowed to adhere to fibrinogen and then solubilized at indicated time points. Proteins from lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to c-Src phosphorylated at Tyr416, c-Src, or RhoA. GTP-bound RhoA was measured by association with GST-RBD beads (25). See Fig. S4 for quantitative data. (B) Spreading of platelets treated with 0.1% DMSO, scrambled control peptide, or mSRI, in the absence or presence of C3 toxin, Y27632, or 0.01 U/ml thrombin. Platelets were stained with Alexa Fluor 546–conjugated phalloidin.

To further determine whether Gα13 mediates inhibition of integrin-induced RhoA-dependent contractile signaling, we investigated the effects of mSRI and depletion of Gα13 on platelet-dependent clot retraction (shrinking and consolidation of a blood clot requires integrin-dependent retraction of platelets from within) (7, 8). Clot retraction was accelerated by mSRI and depletion of Gα13 (Fig. 4, A and B, Fig. S6), indicating that Gα13 negatively regulates RhoA-dependent platelet retraction and coordinates cell spreading and retraction. The coordinated cell spreading-retraction process is also important in wound healing, cell migration and proliferation (23).

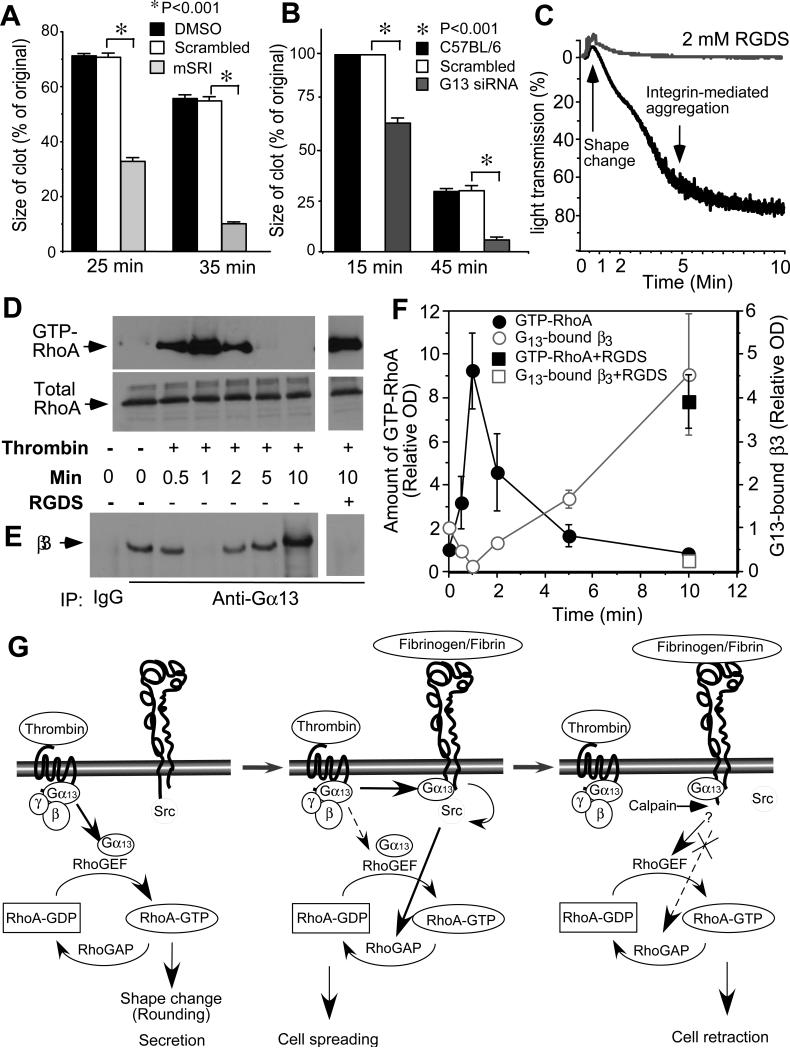

Fig. 4. The role of Gα13 in clot retraction and dynamic RhoA regulation.

(A) Effect of 250 μM mSRI peptide on clot retraction of human platelet-rich plasma compared with DMSO and scrambled peptide. Clot sizes were quantified using Image J (mean±SD, n=3, t-test). (B) Comparison of clot retraction (mean±SD, n=3, t-test) mediated by control siRNA platelets and Gα13-depleted platelets. (C, D, E, F) Platelets were stimulated with thrombin with or without 2 mM RGDS, and monitored for turbidity changes of platelet suspension caused by shape change and aggregation (C). The platelets were then solubilized at indicated time points and analyzed for amount of β3 coimmunoprecipitated with Gα13 (D) and amount of GTP-RhoA bound to GSTRBD beads (E) by immunoblot. (F) quantitative data (mean±SD) from 3 experiments. (G) A schematic illustrating Gα13-dependent dynamic regulation of RhoA and crosstalk between GPCR and integrin signaling.

The function of Gα13 in mediating the integrin-dependent inhibition of RhoA contrasts with the traditional role of Gα13, which is to mediate GPCR-induced activation of RhoA. However, GPCR-mediated activation of RhoA is transient, peaking at 1 minute after exposure of platelets to thrombin, indicating the presence of a negative regulatory signal (Fig. 4, D and F). Furthermore, thrombin-stimulated activation of RhoA occurs during platelet shape change before substantial ligand binding to integrins (Fig. 4, C, D and F). In contrast, following thrombin stimulation, β3 binding to Gα13 was diminished at 1 minute when Gα13-dependent activation of RhoA occurs, but increased after the occurrence of integrin-dependent platelet aggregation (Fig. 4, E and F). Thrombin-stimulated binding of Gα13 to αIIbβ3 and simultaneous RhoA inhibition both require ligand occupancy of αIIbβ3, and are inhibited by the integrin inhibitor RGDS (Fig. 4, D-F). Thus, our study demonstrates not only a function of integrin αIIbβ3 as a non-canonical Gα13-coupled receptor but also a new concept of Gα13-dependent dynamic regulation of RhoA, in which Gα13 mediates initial GPCR-induced RhoA activation and subsequent integrin-dependent RhoA inhibition (Fig. 4G). These findings are important for our understanding on how cells spread, retract, migrate, and proliferate, which is fundamental to development, cancer, immunity, wound healing, hemostasis and thrombosis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by grants from NHLBI, HL080264, HL062350, HL068819 (X.D.) and GM061454 and GM074001 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (T.K.). We thank Dr. Giuseppina Nucifora for help with bone marrow transplantation, Kelly O'Brien and M Keegan Delaney for proof reading.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This manuscript has been accepted for publication in Science. This version has not undergone final editing. Please refer to the complete version of record at http://www.sciencemag.org/. The manuscript may not be reproduced or used in any manner that does not fall within the fair use provisions of the Copyright Act without the prior, written permission of AAAS.

References

- 1.Hynes RO. Cell. 2002;110:673. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ginsberg MH, Partridge A, Shattil SJ. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:509. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ma Y, Qin J, Plow E. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shattil SJ. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:399. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obergfell A, et al. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:265. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arias-Salgado EG, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336149100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flevaris P, et al. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:553. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200703185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flevaris P, et al. Blood. 2009;113:893. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-155978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riobo NA, Manning DR. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:146. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brass LF, Manning DR, Shattil SJ. Prog Hemost Thromb. 1991;10:127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moers A, et al. Nat Med. 2003;9:1418. doi: 10.1038/nm943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kozasa T, et al. Science. 1998;280:2109. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hart MJ, et al. Science. 1998;280:2112. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5372.2112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klages B, Brandt U, Simon MI, Schultz G, Offermanns S. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:745. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.4.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senyuk V, et al. Cancer Res. 2009;69:262. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coller BS. Blood. 1980;55:169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Z, Zhang G, Feil R, Han J, Du X. Blood. 2006;107:965. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gu M, Xi X, Englund GD, Berndt MC, Du X. J. Cell. Biol. 1999;147:1085. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arthur WT, Petch LA, Burridge K. Curr Biol. 2000;10:719. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00537-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanabe S, Kreutz B, Suzuki N, Kozasa T. Methods Enzymol. 2004;390:285. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang JS, Dong L, Kozasa T, Le Breton GC. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:10210. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605678200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vidal C, Geny B, Melle J, Jandrot-Perrus M, Fontenay-Roupie M. Blood. 2002;100:4462. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.13.4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moissoglu K, Schwartz MA. Biol Cell. 2006;98:547. doi: 10.1042/BC20060025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du XP, et al. Cell. 1991;65:409. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90458-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ren XD, Schwartz MA. Methods Enzymol. 2000;325:264. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)25448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.