Abstract

We previously used human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV3) as a vector to express the Ebola virus (EBOV) GP glycoprotein. The resulting HPIV3/EboGP vaccine was immunogenic and protective against EBOV challenge in a non-human primate model. However it remained unclear whether the vaccine would be effective in adults due to pre-existing immunity to HPIV3. Here, the immunogenicity of HPIV3/EboGP was compared in HPIV3-naïve and HPIV3-immune Rhesus monkeys. After a single dose of HPIV3/EboGP, the titers of EBOV-specific serum ELISA or neutralization antibodies were substantially less in HPIV3-immune animals compared to HPIV3-naïve animals. However, after two doses, which were previously determined to be required for complete protection against EBOV challenge, the antibody titers were indistinguishable between the two groups. The vaccine virus appeared to replicate, at a reduced level, in the respiratory tract despite the pre-existing immunity. This may reflect the known ability of HPIV3 to re-infect, and may also reflect the presence of EBOV GP in the vector virion, which confers resistance to neutralization in vitro by HPIV3-specific antibodies. These data suggest that HPIV3/EboGP will be immunogenic in adults as well as children.

Keywords: Virus, Ebola, Vaccine, Mucosal vaccination, Intranasal vaccination, Antibody, Immunity, Vaccine vector, Monkey, Immunogenicity

INTRODUCTION

Ebola virus (EBOV), along with Marburg virus, belongs to the family Filoviridae and causes periodic outbreaks of a severe hemorrhagic fever with a high mortality in Central Africa. The virus is transmitted by direct contact with an infected person, their biological fluids, or cadavers. The virus is highly contagious, and transmission occurs through mucosal surfaces and/or breaks in the skin (reviewed in Sanchez, Geisbert, and Feldmann, 2007). Aerosolized EBOV was demonstrated to cause lethal infections in monkeys (Johnson et al., 1995), and, therefore, the virus is considered a potential agent for biological warfare and bioterrorism. Early attempts to develop a vaccine against EBOV based on inactivated viral particles, purified antigens, and other approaches sometimes were protective in rodents, but were not protective or poorly protective in non-human primates (reviewed in Kuhn, 2008). More recently, vectored vaccines and virus-like particles proved to be protective in non-human primate models (Jones et al., 2005; Sullivan et al., 2000, reviewed in Bukreyev and Collins, 2010).

Human parainfluenza virus type 3 (HPIV3) is a common pediatric respiratory virus. HPIV3 is a member of family Paramyxoviridae, and is an enveloped virus with a single negative-sense strand of genomic RNA of 15,462 nucleotides. Live-attenuated pediatric vaccines against HPIV3 are actively being developed that include the use of HPIV3 as a vector to express protective antigens of other pediatric viruses (Durbin et al., 2000; Karron et al., 2003). Thus, there is substantial experience with the natural history of HPIV3 in humans and with the administration of HPIV3 derivatives in clinical trials. We were interested in evaluating HPIV3 as a potential vector against EBOV and other emerging pathogens because it induces strong mucosal responses in addition to strong systemic responses, and thus should be particularly effective in protecting mucosal surfaces.

We modified HPIV3 to express the EBOV glycoprotein (GP), the only EBOV envelope surface protein, from an additional gene inserted between the HPIV3 P and M genes (Bukreyev et al., 2006).Respiratory tract immunization of guinea pigs with HPIV3/EboGP did not cause any disease or significant lung pathology, and there was no evidence of viral spread beyond the respiratory tract and no evidence of pathologic changes in internal organs (Bukreyev et al., 2009; Bukreyev et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2008). Similarly, HPIV3/EboGP (as well as its wild type HPIV3 parent) was asymptomatic in non-human primates (Bukreyev et al., 2007). The lack of virulence of HPIV3 and its HPIV3/EboGP derivative in non-human experimental animals presumably reflects a host range restriction on this human virus. Thus, evaluation of vectors based on wild type HPIV3 in non-human experimental animals provides a model for attenuated derivatives in humans. There was no evidence that expression of the EBOV GP increased vector replication or tropism in vivo. Indeed, the titers of HPIV3/EboGP in the respiratory tract of guinea pigs and monkeys were similar to or lower than that of the empty HPIV3 vector (Bukreyev et al., 2009; Bukreyev et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2008). More importantly, the vaccine was found to be protective against intraperitoneal challenge with a highly lethal dose of EBOV both in guinea pig and non-human primate models of infection (Bukreyev et al., 2007; Bukreyev et al., 2006). However, essentially all adult humans have pre-existing immunity to HPIV3 from natural exposure. This immunity would be expected to restrict replication of the HPIV3 vector and might drastically reduce the immunogenicity of the foreign insert antigen. Therefore, it was unclear whether this vector would be effective in HPIV3-immune humans. Indeed, pre-existing immunity to other viral vectors such as ones based on vaccinia virus or adenovirus type 5 greatly reduced the immune responses to expressed foreign antigens (see Discussion). Surprisingly, in guinea pigs that had previously been infected with HPIV3, immunization with a single dose of HPIV3/EboGP induced titers of EBOV-specific serum antibodies that nearly equaled those detected in HPIV3-naïve animals (Yang et al., 2008). However, since evaluation of vaccines in rodent models can produce overly optimistic results, testing in non-human primates is an important step in evaluating immunogenicity and efficacy. This is particularly true for filovirus vaccines (Geisbert et al., 2002).

In this study, we evaluated the immunogenicity of HPIV3/EboGP in HPIV3-immune monkeys. We found that pre-existing HPIV3-specific immunity reduced but did not prevent replication of the vaccine in the respiratory tract and that the level of EBOV-specific antibodies was equal to that in HPIV3-naïve primates following two doses of the vaccine.

RESULTS

Two doses of HPIV3/EboGP are equally immunogenic in HPIV3-naïve and HPIV3-immune monkeys

To compare the immunogenicity of HPIV3/EboGP in HPIV3-immune and non-immune animals, we infected fourHPIV3-seronegative monkeys with two doses of HPIV3, four weeks apart, by the combined intranasal (IN) and intratracheal (IT) route. Each dose contained 10650% tissue culture infectious doses (TCID50) per site (Fig. 1). The first dose induced HPIV3-specific hemagglutination inhibition (HAI) serum antibodies with a geometric mean titer of 1:3,400, which was not increased after the second dose (Fig. 2A). Essentially all humans are infected with HPIV3 during infancy and early childhood and may be re-infected thereafter. Thus, the typical adult will have been infected once or more with HPIV3 (hence the animals received two doses), but in most cases will not have been infected recently. A substantial component of the protective cellular immunity induced by HPIV3 infection is lost within a few months (Tao et al., 2000) and, thus, will have been lost in the typical adult. In order to model this situation, the animals were rested for 11 months after the second dose of HPIV3. We detected no reduction in the level of HPIV3-specific serum antibodies over that time (Fig. 2A). Thereafter, two additionalHPIV3-seronegative monkeys were added to the study as HPIV3-naïve controls, and all six animals were immunized with two doses of HPIV3/EboGP, 4 weeks apart, by the combined IN and IT route with 107plaque-forming units (PFU) per site (Fig. 1). We used a 10-fold higher dose of HPIV3/EboGP than HPIV3 because HPIV3/EboGP appeared to be attenuated in vivo compared to HPIV3. For example, HPIV3/EboGP replicated up to 100-fold less efficiently in the lungs of guinea pigs in previous studies (Yang et al, 2008, Bukreyev et al, 2009). This difference was not apparent in an earlier study that monitored shedding from rhesus monkeys (Bukreyev et al, 2007). However, in rhesus monkeys, a dose of 106 TCID50per site of HPIV3 induced a serum antibody response that was not augmented by a second dose and thus appeared to be maximal (as noted above), whereas in a previous study in rhesus monkeys a dose of 107 TCID50per site of HPIV3/EboGP induced a higher serum antibody response to the vector and the insert than did a dose of 2×106 TCID50per site (Bukreyev, 2007), suggesting that the higher dose would be necessary to approach a maximal response.

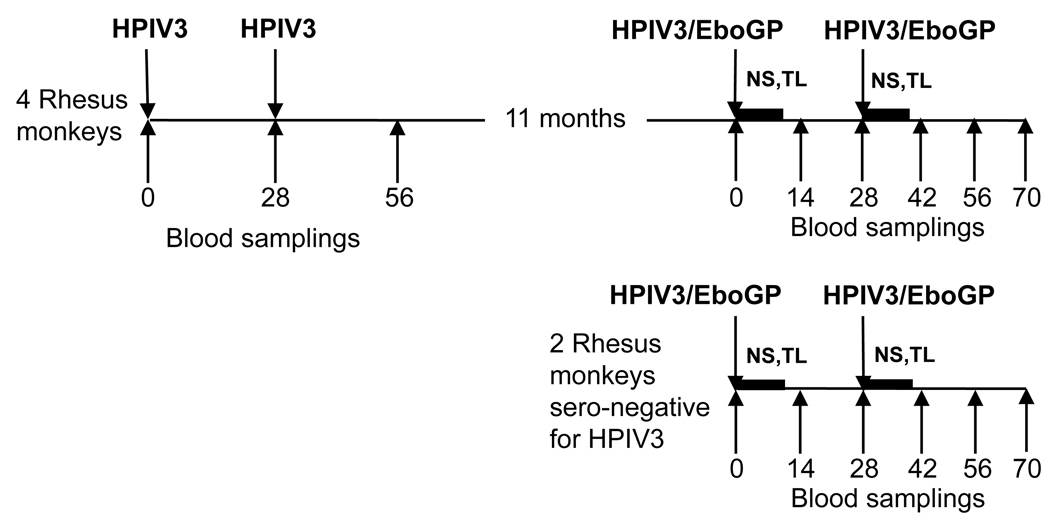

Fig. 1.

Design of the study. The arrows above the horizontal lines indicate virus inoculations, and those below indicate days of blood sample collection. Days of virus inoculations and blood samplings are counted after the first dose of HPIV3 (left side) or the first dose of HPIV3/EboGP (right side). The horizontal bars indicate collections of NS and TL on days 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10.

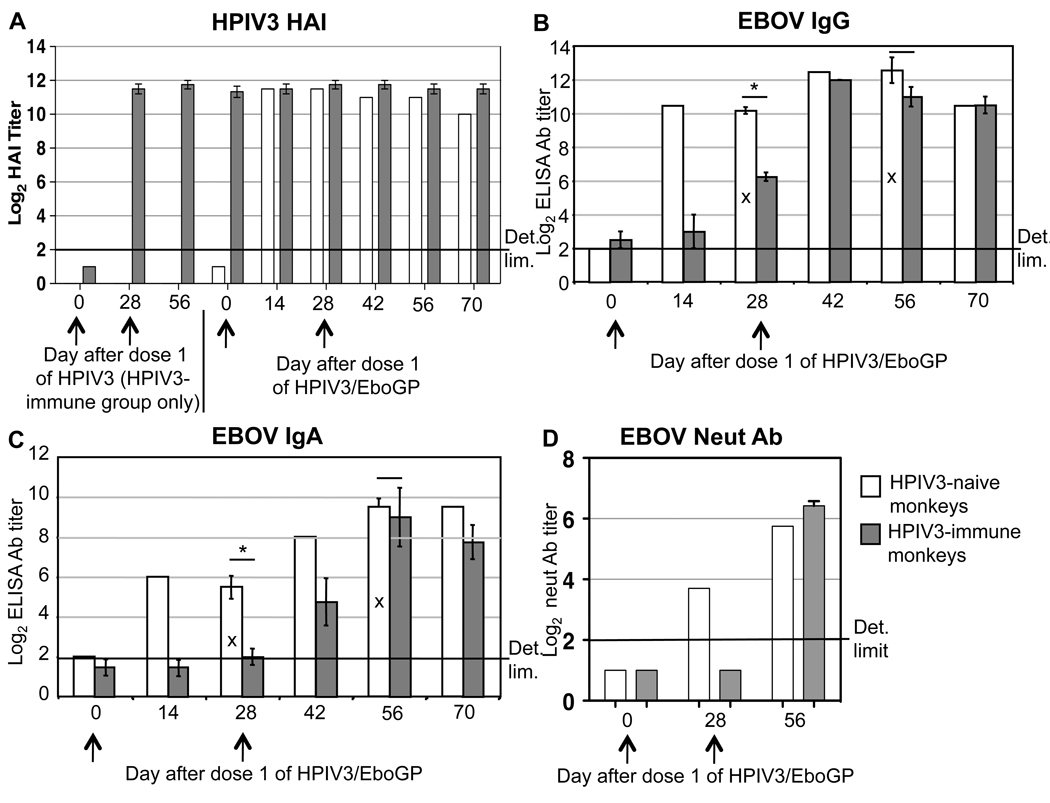

Fig. 2.

Immunogenicity of HPIV3/EboGP in HPIV3-immune (grey bars) and HPIV3-naïve (white bars) monkeys. The days on which HPIV3 (A, left side) or HPIV3/EboGP (A, right side, B, C, D) were administered are indicated with arrows. The days after dose 1 of HPIV3 (A, left side) or HPIV3/EboGP (A, right side, B, C, D) are indicated. All titers are expressed as reciprocal mean log2 values. A. HPIV3-specific serum antibody (Ab) levels determined by HAI. Left side, antibody titers (HPIV3-immune group only) after infection with HPIV3, mean values ± SE for the four animals in the group; right side, antibody titers after infection with HPIV3/EboGP of the two HPIV3-naïve animals, mean values, and the four HPIV3-immune animals, mean values ± SE. B, C, EBOV-specific serum IgG (B) and IgA (C) quantitated by ELISA using inactivated purified EBOV as antigen. Mean titers of the two HPIV3-naïve and mean titers ± SE of the four HPIV3-immune animals are shown. However, for days 28 and 56 (bars indicated with X), the data for the two HPIV3-naïve animals were augmented by analysis, in parallel, of samples from three additional animals from a previous study in which the monkeys were immunized exactly as in the present study (Bukreyev et al., 2007): thus, for these time points, the HPIV3-naïve group is represented by mean values ± SE of a total of five samples. D. EBOV-neutralizing (neut) serum antibodies analyzed using VSVΔG/ZEBOVGP, which is a recombinant VSV bearing an envelope in which EBOV GP is the sole viral surface antigen. Mean titers of the two HPIV3-naïve and mean titers ± SE of the four HPIV3-immune animals are shown. Comparisons of IgG and IgA responses (panels B and C, respectively) between the HPIV3-naïve and the HPIV3-immune monkeys on days 28 and 56 are indicated by horizontal lines; statistically significant differences (p<0.05) are indicated by asterisks. For the samples in which antibodies were not detected, the value 1 log2 was assigned for calculation of the mean (panels A, C, D).

We previously demonstrated that two doses of HPIV3/EboGP are required for a uniform protection against EBOV challenge in a non-human primate model (Bukreyev et al., 2007). Consistent with that study, administration of the first dose of HPIV3/EboGP to HPIV3-naïve animals in the present study induced substantial titers of serum EBOV-specific IgG and IgA, as quantified by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Fig. 2B, C). The second dose of HPIV3/EboGP was followed by a modest increase in the antibody titers, although by day 42 after the second dose the titer of serum IgG, but not IgA, diminished to that induced by the first dose (Fig. 2B, C). Titers of EBOV-neutralizing antibodies were assayed by the ability to neutralizethe virus VSVΔG/ZEBOVGP(Garbutt et al., 2004), which is a recombinant version of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) in which the VSV envelope glycoprotein G was deleted and replaced by EBOV GP as the sole viral surface protein. This chimeric virus depends on EBOV GP for cell attachment and entry, and therefore is a suitable alternative in neutralization assays tothe authentic EBOV Zaire virus, which requires a biosafety level (BSL)-4 facility. In the HPIV3-naïve animals immunized with HPIV3/EboGP, we detected a 1:13 geometric mean titer of EBOV-neutralizing antibodies after the first dose, which increased after the second dose to 1:54 (Fig. 2D).

In the HPIV3-immune monkeys, the first dose of HIPV3/EboGP induced titers of EBOV-specific serum IgG and IgA antibodies that were significantly reduced compared to the HPIV3-naïve monkeys (Fig. 2B, C). However, following the second dose, the titers of serum IgG and IgA in HPIV3-immune animals were essentially equal to those in the HIPV3-naïve animals. The EBOV-neutralizing antibodies were not detectable after the first dose; however, after the second dose, the geometric mean titer 1:85 was detected that exceeded the titer in the HPIV3-naïve group (Fig. 2D). These data indicate that two doses of HPIV3/EboGP were as immunogenic in HPIV3-immune monkeys as in HPIV3-naïve monkeys. We also performed the neutralization assay of sera from the two HPIV3-naïve and two HPIV3-immune animals in the absence of guinea pig complement. Interestingly, little or no EBOV-neutralizing activity was detectable in most of the samples. In particular, low titers, 1:9 and 1:6, were detected in sera from one HPIV3-naïve and one HPIV3-immune monkey, respectively, after the second but not the first dose (data not shown). These data suggest that at least in the case of vaccination with HPIV3/EboGP, the complement system is an important component of EBOV neutralization by antibodies.

Pre-existing vector-specific immunity does not prevent replication of the vaccine in the respiratory tract

In the experiment shown in Fig. 1, nasal swabs (NS) and tracheal lavages (TL) were collected after immunization of HPIV3-naïve and -immune animals with HPIV3/EboGP (Fig. 1) in order to measure vaccine virus shedding. The samples were assayed by plaque titration and the titers were expressed as PFU/ml of NS or TL fluids. Relatively high titers of viable vaccine viruswere detected in NS and TL specimens collected from HPIV3-naïve monkeys on days 2, 4, 6, but not days 8 and 10, after the first dose of the vaccine (Fig. 3A). In contrast, infectious virus was not detected in NS and TL specimens collected from the HPIV3-immune monkeys. Furthermore, infectious virus was not detected in NS and TL specimens from either group collected after the second dose of the vaccine. These data suggested that the immunity induced by HPIV3 or HPIV3/EboGP strongly restricted replication of a subsequent dose of HPIV3/EboGP. However, we previously showed that UV-inactivated HPIV3/EboGP induced only a low level of EBOV-specific serum antibody in guinea pig model, indicating that a significant immune response to HPIV3/EboGP depends on its replication (Yang et al., 2008). As noted later in this report, UV-inactivated HPIV3/EboGP also did not induce detectable IgG or IgA ELISA serum antibodies in HPIV3-naïve Rhesus monkeys, showing that replication is necessary for significant immunogenicity in non-human primates. Thus, the increase in the immune response to each doses of HPIV3/EboGP in HPIV3-immune monkeys in the present study raised the possibility that replication of HPIV3/EboGP was occurring following each dose even though infectious virus was not detectable in any of the NS and TL specimens by plaque assay.

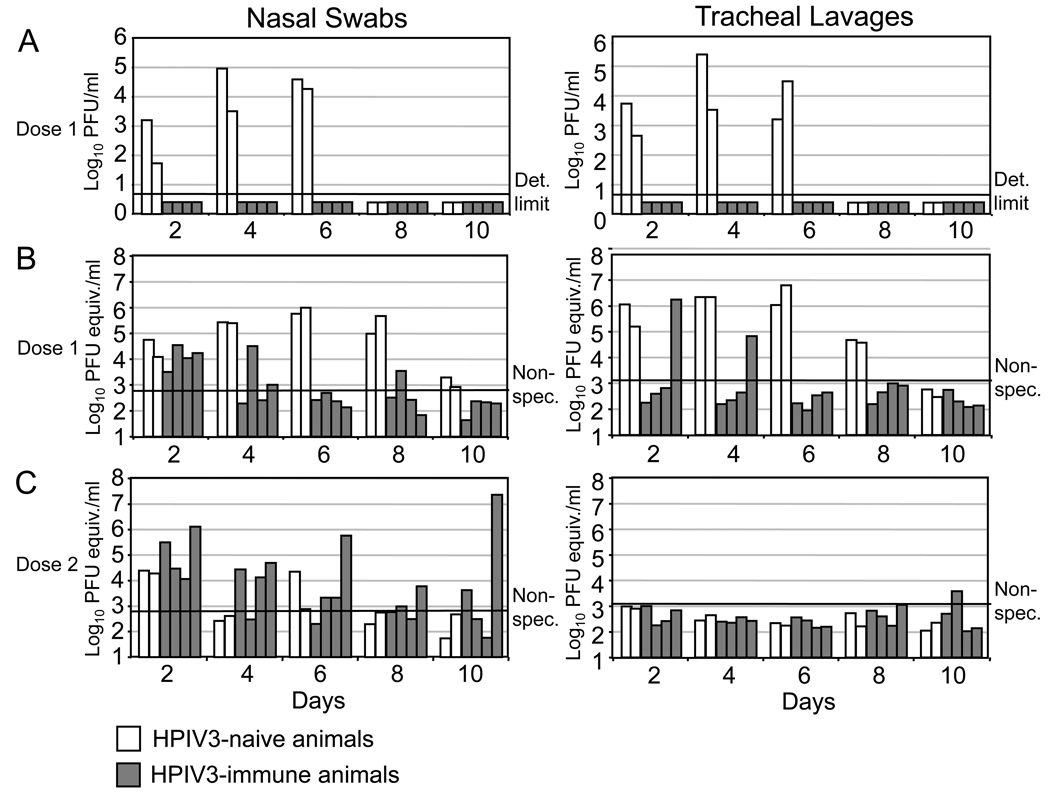

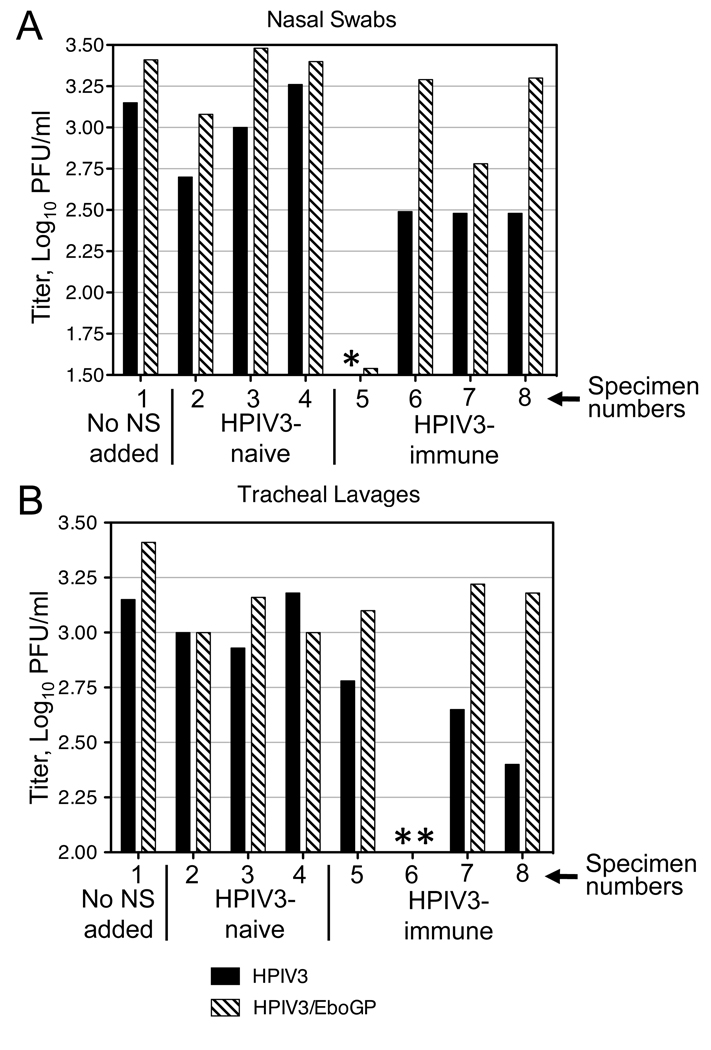

Fig. 3.

Shedding of the HPIV3/EboGP vaccine virus in HPIV3-naïve and HPIV3-immune monkeys. NS and TL samples were collected on the indicated days and analyzed later in parallel by plaque titration or quantitative RT-PCR. Each bar represents an individual monkey.A. Plaque titration of NS and TL specimens after dose 1. The limit of detection was 5 PFU/ml; for the samples in which virus was not detected, values two-fold below the limit of detection were assigned. Virus was not detected in any animal after dose 2 (see Results).B, C. Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of NS and TL specimens after dose 1 (B) and dose 2 (C). The quantitative RT-PCR results are expressed as PFU/ml based on comparison with a standard curve constructed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis of RNA samples from serial dilutions of a preparation of HPIV3/EboGP with a known PFU/ml concentration. The non-specific background signal, determined using NS and TL from monkeys from an unpublished study that were inoculated with a Newcastle disease virus vector, was 2.8–2.9 and 3.0–3.1 log10 PFU equivalents/ml in NS and TL, respectively. The assay was repeated four times.

We therefore used quantitative reverse transcription – polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) to quantify HPIV3 RNA present in NS and TL specimens from HPIV3-naïve and HPIV3-immune monkeys. As a control, analysis of specimens from two monkeys infected with an unrelated viral vector (i.e., samples collected on day 4 after IN and IT inoculation of Rhesus monkeys with 107 PFU of a recombinant Newcastle disease virus expressing EBOV GP [J.M.D., P.L.C., A.B., unpublished data]) indicated that the non-specific background was 2.8–2.9 and 3.0–3.1 log10 PFU equivalents/ml in NS and TL, respectively. After the first dose of HPIV3/EboGP in HPIV3-naïve animals, the level of viral RNA significantly exceeded this non-specific control in both the NS and TL for most of the time points. Importantly, substantial concentrations of the viral RNA also were detected in many of the NS and TL specimens from HPIV3-immune monkeys, mostly on days 2 and 4 (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, after the second dose of HPIV3/EboGP, high concentrations of HPIV3 RNA were detected in NS specimens of both HPIV3-naïve and HPIV3-immune animals, whereas little or no HPIV3 RNA was detected in TL specimens (Fig. 3C). These data indicate that RNA from the HPIV3 vector is present in the respiratory tract of both HPIV3-naïve and HPIV3-immune monkeys not only after the first dose of HPIV3/EboGP, but also after the second dose.

Replication of HPIV3/EboGP is necessary for RNA detection in NS and TL speciments and for immunogenicity

We next asked whether the vector RNA detected in the respiratory tract secretions represents progeny virus produced by viral replication in vivo or represents the initial viral inoculum. To distinguish between these two possibilities, we performed a separate experiment with four seronegative Rhesus monkeys in which two monkeys were inoculated with live HPIV3/EboGP and two with UV-inactivated HPIV3/EboGP. The animals received either virus by the combined IN and IT route at 107 PFU (or its equivalent) per site. On days 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10, NS and TL were collected and analyzed for the presence of viable virus by plaque titration (Fig. 4A) or for the presence of HPIV3 RNA by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 4B). As expected, plaque assay of the NS and TL specimens collected from the two monkeys that received live HPIV3/EboGP virus revealed viral titers comparable to those observed in the first monkey experiment (as was shown in Fig. 3A), whereas no infectious virus was detected in specimens from the two animals that received UV-inactivated HPIV3/EboGP (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, quantitative RT-PCR demonstrated the presence of HPIV3 RNA in the NS and TL samples of the monkeys inoculated with live HPIV3/EboGP, at concentrations comparable to those observed in the first monkey experiment (as was shown in Fig. 3B), but not in the samples collected from the monkeys inoculated with UV-inactivated HPIV3/EboGP (Fig. 4B).

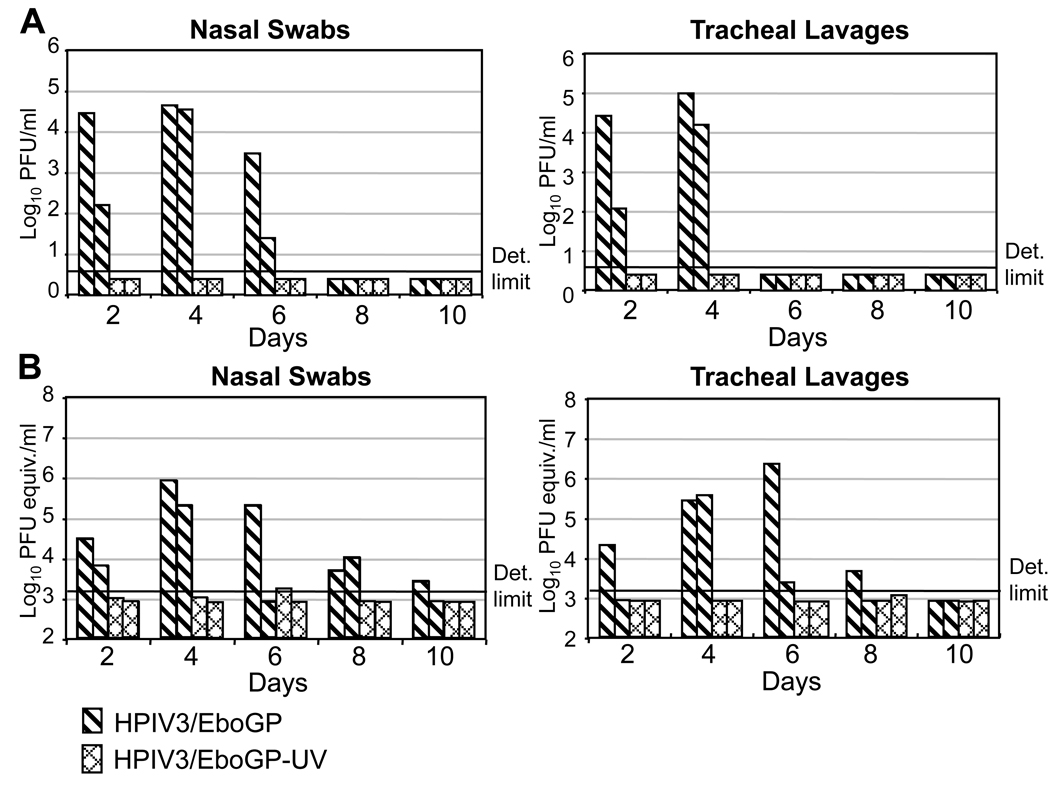

Fig. 4.

Analysis of NS and TL specimens collected after inoculation of HPIV3-naïve monkeys with HPIV3/EboGP or UV-inactivated HPIV3/EboGP for the presence of infectious virus by plaque titration (A) or the presence of HPIV3/EboGP RNA by quantitative RT-PCR (B) calculated as in the assay shown in Fig. 3 (B, C). Each bar represents an individual monkey. In part A, the limit of detection was 5 PFU/ml; for the samples in which no virus was detected, values two-fold below the limit of detection were assigned. In part B, the value 2.9 log10, which is 2-fold below the limit of detection and represents the titer detected in the last (least concentrated) dilution of the HPIV3/EboGP standard curve, was assigned to the samples in which RNA was not detected. The assay was repeated two times.

As a control, we compared the sensitivity of quantitative RT-PCR for live versus UV-inactivated HPIV3/EboGP. We found that UV inactivation reduced the sensitivity of the assay by 1.7 log10 (not shown). This loss in sensitivity presumably is due to damage to most of the RNA template by the introduction of uracil dimers, since even with the UV dose minimally required for a complete inactivation of the virus used here, a large fraction of the RNA molecules received multiple hits. In any event, this value is well below the difference between the levels of RNA in some of the NS and TL samples positive for the viral RNA and the limit of detection. For example, the difference between the levels of RNA detected in some monkeys on days 4 and 6 and the limit of detection (3.2 log10) was 2.7 and 3.1 log10 for NS and TL, respectively (Fig. 4B).This indicates that the HPIV3 vector RNA that was detected in NS and TL specimens following the first and second inoculation with HPIV3/EboGP was due to replicated virus rather than residual inoculum.

Finally, we collected serum samples 28 and 56 days following immunization with UV-inactivated versus infectious HPIV3/EboGP. The UV-inactivated virus did not induce detectable EBOV-specific ELISA IgG or IgA serum antibodies, whereas strong responses were observed in animals that received infectious HPIV3/EboGP, similar to results described above and in previous work (not shown). This confirmed that replication of HPIV3/EboGP was necessary for significant EBOV-specific antibody responses in primates, as had previously been observed in guinea pigs (Yang et al., 2008).

NS and TL specimens from HPIV3-immune animals neutralize the infectivity of HPIV3 and HPIV3/EboGP in vitro

We next attempted to determine why the HPIV3/EboGP vaccine virus was detectable in respiratory secretions by quantitative RT-PCR, but not by plaque titration. One possibility was that HPIV3/EboGP indeed was secreted from the respiratory tract epithelial cells, but was neutralized by HPIV3-specific antibodies present in the respiratory tract either immediately upon its release, or in vitro during analysis of the specimens by plaque assay. To investigate this possibility, we performed spiking experiments in vitro in which replicate aliquots of 150 µl containing 300 PFU of either HPIV3 or HPIV3/EboGP were mixed with 150 µl of NS or TL specimen from the HPIV3-naïve or -immune animals indicated in Fig. 3. As a control, we tested one set of specimens (number 2 in Fig. 5) collected on day 4 after infection with Newcastle disease virus (from an unpublished study), in which no HPIV3-specific neutralizing antibodies would be expected to be present. We also assayed two sets of specimens (number 3 and 4) collected from HPIV3-naïve monkeys on day 2 after infection with the first dose of HPIV3/EboGP. Day 2 is an early time point when any HPIV3-specific neutralizing activity present in the serum or in the respiratory tract secretions would be due to antibodies present before infection with HPIV3/EboGP (i.e., present from the original HPIV3 infections 11 months earlier). Other samples included four sets of specimens (numbers 5–8) collected from HPIV3-immune animals on day 2 after the first dose of HPIV3/EboGP. All of the NS and TL specimens were UV-irradiated to destroy any infectious HPIV3/EboGP, which was confirmed by plaque assay. The mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37°C, and the residual titers of spiked virus were quantified by plaque titration (Fig. 5). We found no consistent reduction in viral titers by NS specimens collected from the HPIV3-naïve monkeys. In contrast, the number of PFU of HPIV3 was reduced by all four NS samples from the HPIV3-immune monkeys by 4.5-fold to at least 560-fold (below the limit of detection for NS number 5) and that of HPIV3/EboGP was reduced by two out of four NS samplesby 74- and 4.3-fold. TL specimens collected from the HPIV3-naïve monkeys only marginally reduced titers of both viruses; however, the reduction was much greater in the case of TL specimens collected from the HPIV3-immune animals. In particular, the titers of HPIV3 were reduced by 2.3- to at least 560-fold (below the limit of detection for TL number 6), and those of HPIV3/EboGP were slightly reduced (by 1.6 to 2.1-fold), or reduced to undetectable level (i.e. by at least 1,040-fold) by TL number 6. The seemingly greater resistance to HPIV3/EboGP to neutralization by HPIV3-immune NS and TL specimens would be consistent with our previous finding that HPIV3/EboGP is less susceptible than the HPIV3 empty vector to neutralization by HPIV3-specific antibodies due to the presence of functional EBOV GP incorporated into the vector particle (Bukreyev et al., 2006), although the number of monkeys examined here was insufficient to unequivocally demonstrate this effect. We also tested the respiratory tract secretions for the ability to neutralize added human respiratory syncytial virus, a serologically unrelated paramyxovirus, and found a lack of any significant neutralizing activity (not shown). This supports the idea that the neutralizing activity against HPIV3 and HPIV3/EboGP was specific. These data indicate that HPIV3-specific antibodies present in NS and TL specimens can neutralize HPIV3 and HPIV3/EboGP, and thus virus that is shed and present in respiratory secretions from HPIV3-immune (and HPIV3/EboGP-immune) monkeys might be missed by plaque titration.

Fig. 5.

Evaluation of the ability of NS (A) and TL (B) fluids collected from HPIV3-naïve and HPIV3-immune monkeys to neutralize HPIV3 wild type virus (black bars) or the HPIV3/EboGP vaccine virus (striped bars) added in vitro at 103 PFU/ml. The following NS and TL specimens or control were combined with HPIV3 or HPIV3/EboGP in the neutralization test: 1, Control in which phosphate buffered saline was added to the HPIV3 or HPIV3/EboGP preparations; 2, NS and TL specimens collected on day 4 after infection of a rhesus monkey with 2×107 PFU of Newcastle disease virus in a previous unpublished study;3 and 4, NS and TL specimens collected from two different HPIV3-naïve monkeys collected on day 2 after the first dose of HPIV3/EboGP; 5 – 8, NS or TL samples collected from four different HPIV3-immune monkeys collected on day 2 after the first dose of HPIV3/EboGP. All specimens were UV-irradiated before use in order to inactivate shed virus. The added test virus was completely neutralized in the case of HPIV3, NS number 5 (indicated with a single asterisk) and for both HPIV3 and HPIV3/EboGP in the case of TL number 6 (two asterisks). The limit of detection was 5 PFU/ml.

DISCUSSION

This report demonstrated that an HPIV3-vectored vaccine against EBOV replicates and is immunogenic in HPIV3-immune non-human primates. Indeed, the levels of EBOV-specific serum antibodies detected by ELISA, an important correlate of protection for EBOV (reviewed in Sullivan et al., 2009) or by a neutralization assay following two doses of the vaccine were indistinguishable from those of HPIV3-naïve animals. These results contrast with similar studies involving vaccinations with two or even three doses of other vectors based on common human viral pathogens such as vaccinia virus and adenovirus type 5 administered by intramuscular route. For example, following immunization of Rhesus monkeys with a vaccinia virus-vectored vaccine expressing the simian immunodeficiency virus group antigen (gag) protein, gag-specific cytotoxic T cell (CTL) responses were severely attenuated by pre-existing immunity to the vaccinia virus vector (Sharpe et al., 2001). In clinical trials, a vaccinia virus-vectored vaccine against Japanese encephalitis virus induced neutralizing serum antibody responses only in vaccinees that did not have prior immunity to vaccinia virus (Kanesa-Thasan et al., 2000). Similarly, pre-exposure of mice and Rhesus monkeys to human adenovirus type 5, the serotype most common in the human population, severely attenuated the immune response to the gag protein of human immunodeficiency virus type I or simian immunodeficiency virus expressed by a vaccine based on this vector (Barouch et al., 2004; Casimiro et al., 2003; Lemckert et al., 2005; McCoy et al., 2007). Similarly, pre-exposure of mice to human adenovirus type 5 greatly reduced the EBOV-specific antibody and cell-mediated responses to an adenovirus 5-based vector expressing the EBOV GP (Yang et al., 2003).

UV-inactivation of the HPIV3/EboGP vaccine abrogated its immunogenicity in guinea pigs (Yang et al., 2008) and non-human primates (present study), indicating that its immunogenicity depends on replication. Therefore, the observation that HPIV3/EboGP was immunogenic in HPIV3-immune animals following each of the two doses suggested that at least some replication of HPIV3/EboGP occurred following each dose despite pre-existing immunity. Indeed, quantitative RT-PCR demonstrated the presence of HPIV3-specific RNA in NS and TL specimens from both HPIV3-naïve and HPIV3-immune animals following each dose of HPIV3/EboGP. These data are consistent with a recently published study (Boukhvalova, Prince, and Blanco, 2007) in cotton rats with respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), which, like HPIV3, is a respiratory paramyxovirus with the ability to cause re-infections (reviewed in Collins and Crowe, 2007). That study demonstrated that, in cotton rats previously infected with RSV, a second RSV infection does not result in any detectable PFU in the lungs, as evaluated by plaque assay of homogenates of the harvested lungs. However, quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the lung tissues demonstrated substantial titers of viral RNA, which at early time points were comparable to those during the primary infection. The authors interpreted this data to suggest that pre-existing RSV immunity led to "abortive replication" in the respiratory tract tissues of infected animals. However, they did not address the alternative possibility that the second infection might lead to the production of progeny virus that was subsequently neutralized by endogenous antibodies, either in vivo or in the context of their in vitro plaque assay. Our study, which analyzed respiratory secretions rather than lung tissue, showed that the NS and TL specimens from HPIV3-immune animals, but not from HPIV3-naïve animals, neutralized added HPIV3 or HPIV3/EboGP in vitro, indicating the presence of neutralizing antibodies. The presence of virus-specific antibodies in mucosal secretions after infection with respiratory viruses is well known (Brown et al., 1985; Burlington et al., 1983). This suggests that progeny HPIV3/EboGP was produced and shed into the respiratory tract, but was neutralized by antibodies present in the respiratory secretions. This is offered with the caveat that we did not demonstrate that the viral RNA present in the NS and TL samples was in the form of virus particles.

How was HPIV3/EboGP able to replicate in the respiratory tract in the presence of pre-existing HPIV3-specific immunity? One explanation may lie in the ability of respiratory paramyxoviruses, including HPIV3 and RSV, to re-infect throughout life despite the presence of immunity due to prior infection. This appears to be due to several factors. For example, the rises in virus-specific secretory IgA titer in the respiratory tract that occur following infection can diminish within months. Virus-specific serum antibody responses are longer-lived, but these antibodies gain access to the respiratory lumen inefficiently, limiting their ability to restrict virus replication in luminal epithelial cells. Virus-specific CTL induced by infection diminish within a few months, and secondary responses may not be fast enough to prevent extensive virus replication. Furthermore, a number of laboratories have presented evidence that virus-specific CTL are functionally down-regulated in the respiratory tract, presumably as a means of limiting their ability to damage tissue (Claassen et al., 2005; DiNapoli et al., 2008; Fulton, Olson, and Varga, 2008; Gray et al., 2005; Vallbracht, Unsold, and Ehl, 2006). Taken together, these factors limit the ability of pre-existing immunity to restrict re-infection by respiratory viruses (reviewed in Collins and Crowe, 2007; Karron and Collins, 2007). In agreement with this, the above-noted suppressive effect of the pre-existing antibodies on human adenovirus-5-vectored vaccine against EBOV delivered intramuscularly was bypassed by intranasal delivery of the vaccine, at least in mice (Croyle et al., 2008); no such results have been reported for non-human primates so far. Another explanation may be related to a relatively high, 2×107 PFU, dose of the vaccine virus, which might not be fully neutralized by the amount of HPIV3-specific antibodies available locally in the respiratory tract. The third explanation may lie in the presence of functional EBOV GP in the HPIV3/EboGP envelope. As already noted, EBOV GP is incorporated into the HPIV3/EboGP viral particles, conferring the ability to evade efficient neutralization by HPIV3-specific antibodies in vitro (Bukreyev et al., 2006). Thus, EBOV GP may be mediating virus attachment and entry in the respiratory tract of both naïve and HPIV3-immune non-human primates, thereby further circumventing the neutralizing antibody response against HPIV3.

How can this limited level of replication induce an immune response in HPIV3-immune animals that attains the level observed in HPIV3-naïve animals? Several studies in which mice were inoculated with respiratory viruses by the IN route demonstrated that migration of activated dendritic cells from the lungs into the draining lymph nodes occurs within hours post infection. In particular, after infection of mice with Sendai virus, a murine paramyxovirus closely related to HPIV1 and HPIV3, lung dendritic cells were detected in peribronchial lymph nodes at 6–12 h post infection (Grayson et al., 2007). Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection of mice resulted in the accumulation of lung dendritic cells in mediastinal lymph nodes at 12 h, the earliest time point tested, and reached a peak 18 h post infection (Lukens et al., 2009). After infection of mice with influenza A virus, accumulation of lung dendritic cells in peribronchial lymph nodes was detected as early as 6 h and reached a maximum 18 h post infection. Moreover, at 48 h following infection in mice, pulmonary dendritic cells became refractory to activation by a secondary infection with an unrelated strain of the virus (Legge and Braciale, 2003). These data suggest that the activation of respiratory dendritic cells resulting in migration to secondary lymphoid tissue is primarily an early event during virus infection. It appears to be mediated mostly by early viral progeny produced after a limited number of infection cycles rather than by virus produced later at the peak of viral replication. In this regard, it is noteworthy that the detection of HPIV3 RNA following inoculation of HPIV3-immune animals with HPIV3/EboGP was greatest on day 2 post-immunization, with detection subsequently declining with increasing time. At this early time, the amount of vector RNA was similar between HPIV3-immune and -naïve animals in the NS specimens and was somewhat reduced in the TL specimens from HPIV3-immune animals. Thus, three features of the HPIV3/EboGP vaccine may contribute to its immunogenicity in vector-immune animals: first, the inefficiency of pre-existing immunity in restricting HPIV3 replication; second, the presence of a functional EBOV GP; and third, the disproportionate role of early activation of respiratory antigen-presenting cells in the adaptive response.

It should be noted that we did not measure EBOV-specific cell-mediated responses in this particular study. Cell-mediated responses have been described to be required for protection of monkeys against EBOV challenge after vaccination with adenovirus type 5-vectored vaccine (Sullivan et al., 2009), although the details of this study have not yet been published. However, we previously showed that administration of HPIV3/EboGP to the respiratory tract of non-human primates results in only a low, sporadic cellular response detected in the peripheral blood, which might be a consequence of the cellular response accumulating at the respiratory tract site of infection (reviewed in Bukreyev and Collins, 2010). Thus, we did not monitor cell-mediated responses in the present study. In contrast, the serum antibody response is robust, whether measured by ELISA or neutralizing assays, and likely plays an important role in protection (reviewed in Bukreyev and Collins, 2010). Furthermore, we did not test the protective efficacy of the vaccine in the HPIV3-immune animals in the present study due to a current unavailability of a BSL-4 facility. This important experiment will be performed in follow-up studies, although we note that the levels of serum ELISA and neutralizing antibodies observed in the present study would be consistent with a high level of protection. It should also be noted that the combined IN and IT route of inoculation was used in our non-human primate studies in an effort to achieve uniform infection of the animals, which is essential in studies involving a small number of animals. While IT delivery would not be feasible in humans, delivery by the IN route alone should be sufficient since humans are the natural host for the HPIV3 vector and are more permissive than non-human primates. Alternatively, the vaccine can be delivered in form of aerosol using a nebulizer. This mode of delivery was previously used to successfully deliver measles virus vaccine to four million children (Fernandez Bracho and Roldan Fernandez, 1990: Fernandez-de Castro et al., 1997), and a similar apparatus was recently used for evaluating a vectored respiratory tract vaccine against H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in monkeys (Dinapoli et al., 2009).

The present data suggest that the effectiveness of an HPIV3-based vector may not be strongly suppressed by pre-existing immunity to the vector. We also have developed an alternative strategy to circumvent the moderate suppression of immunogenicity by pre-existing immunity to the HPIV3 vector. Specifically, we developed an HPIV3-based construct, HPIV3/ΔF-HN/EboGP, in which the HPIV3 F and HN genes, which encode the neutralization and major protective antigens of HPIV3, were replaced by EBOV GP (Bukreyev et al., 2009).TheHPIV3/ΔF-HN/EboGPvirus was insensitive to HPIV3-neutralizing antibodies in vitro, was highly attenuated in guinea pigs, was strongly immunogenic in HPV3-immune and -naïve animals, and was completely protective against EBOV challenge. Either type of vaccine virus is a candidate for clinical trials in adults. Boththe HPIV3/EboGP and theHPIV3/ΔF-HN/EboGP vaccines have several important advantages. First, they do not replicate beyond the respiratory tract and therefore are very safe. Second, they induce not only systemic, but also local immune responses in the respiratory tract, a possible port of entry of EBOV. Third, they are needle-free, increasing the safety and ease of administration by IN route, which is likely to be as effective as the combined IN and IT route tested in the present study due to the full permissiveness of human to the HPIV3 vector. Fourth, their production would be relatively straight-forward, since both of the vaccines represent replication-competent viruses capable of effective replication in cell lines approved for vaccine production, such as Vero, and do not require enhanced safety under BSL-3 or BSL-4 containment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Immunization of rhesus monkeys

Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) were from morgan Island, SC, and weighed from 3.6 to 4.8 kg. Prior to use, all animals were determined to HPIV3-seronegative by an HPIV3-specific HAI assay, with reciprocal HAI titers < 4. Two studies were performed. In the first study (Fig. 1–Fig 3), we infected four HPIV3-seronegative monkeys with two dosed, four weeks apart, of HPIV3 by the combined IN and IT route with 106 TCUD50 per site, as previously described (Bukreyev et al., 2004). Eleven months after the second dose of HPIV3, two additional HPIV3-seronegative monkeys were introduced into the study, and all six animals were inoculated with the HPIV3/EboGP vaccine by the combined IN and IT routed with 107 PFU per site as above. Four weeks later, a second dose of the vaccine was administered identically to the first dose. NS and TL were collected on days 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 after the first and the second doses of the vaccine as previously described (Bukreyev et al., 2004), In the second study (Fig. 4), we immunized two HPIV3-seronegative monkeys with a single dose of HPIV3/EboGP and two additional HPIV3-seronegative monkeys with a single dose of UV-inactivated HPIV3/EboGP.Immunizations wereperformed by the combined IN and IT routewith a dose 107 PFU or its inactivated equivalent per site. NS and TL samples were collected as above. The first experiment was performed at Bioqual, Inc. (Rockville, MD), and the second at an NIAID facility (Poolesville, MD); both sitesare approved by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Care International. All procedures were performed in accordance with protocols and guidelines approved by the NIAID Animal Care and Use Committee.

Viruses and virological assays

HPIV3 and HPIV3/EboGP (Bukreyev et al., 2006) were propagated in LLC-MK2 monkey kidney cells. The chimeric VSV-based virus VSVΔG/ZEBOVGP(Garbutt et al., 2004), in which the VSV envelope protein G had been replaced with the GP of EBOV, was kindly provided by Dr. Heinz Feldmann (Laboratory of Virology, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIAID, NIH) and was propagated and titrated in Vero cells. UV-inactivation of HPIV3/EboGP was performed with a UV Stratalinker 1800 (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using a UV dose of 128 mJoules, which was determined to be the minimal dose required forcomplete inactivation of infectivity of the preparation. Titers of HPIV3/EboGP were determined by plaque titration in LLC-MK2 cells visualized by immunostaining, as previously described (Bukreyev et al., 2006). Titers of HPIV3 were determined by limiting dilution in LLC-MK2 cells and expressed as TCID50/ml. For analysis of HPIV3/EboGP by quantitative RT-PCR, total RNA was isolated from the cell culture medium or from NS and TL specimens using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) according manufacturer's recommendations. The RNA was subjected to reverse transcription with random hexamer DNA primers, and analyzed by quantitative PCR using primers specific for the nucleoprotein gene of HPIV3 and the TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), as previously described (Yang et al., 2008).

Serological assays

HPIV3-specific serum antibody responses were determined by HAI assay in which serum dilutions were tested for the ability to block agglutination of guinea pig erythrocytes by HPIV3, as previously described (van Wyke Coelingh, Winter, and Murphy, 1985). EBOV-specific antibody responses were determined by ELISA, in which purified gamma-irradiated EBOV was used as an antigen, as previously described (Yang et al., 2008). To quantify EBOV-neutralizing titers, we tested the ability of the sera to neutralize VSVΔG/ZEBOVGP (Garbutt et al., 2004). Serial dilutions of heat-inactivated monkey sera prepared in Opti-Pro medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were mixed with an equal volume of the virus. The virus dilutionswere prepared in tissue culture medium in the absence or presence of guinea pig complement (Lonza Inc., Allendale, NJ) such that the final concentration in the neutralization mixtures was 1 TCID50 /µl and 5% (v/v) of complement. The serum/virus mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 1 h,and 50 µl of each sample (equivalent to 50 TCID50 of input virus) were added to confluent monolayers of Vero cells in replicate of 4. Wells were scored for virus replication by visual determination of cytopathic effects (CPE) at 48 and 72 h post-infection. The serum neutralizing titer is reported as the highest serum dilution that results in complete virus neutralization in 50% of the wells, as calculated using the method of Reed and Muench (Reed and Muench, 1938).

Statistics calculations

Statistical significances were calculated by Student's T test.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Anthony Sanchez (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA) for providing gamma-irradiated purified EBOV antigen for ELISA, and Dr. Heinz Feldmann (Laboratory of Virology, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIAID, NIH) for providing VSVΔG/ZEBOVGP. We also thank Fatemeh Davoodi (Laboratory of Infectious Diseases, NIAID, NIH) for performing HAI assays, as well as Brad Finneyfrock and Dr. Anthony Cook (Bioqual, Inc.), and Stacey Miller (Comparative Medicine Branch, NIAID) for their assistance with primate studies. This research was supported by the NIAID Intramural Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Barouch DH, Pau MG, Custers JH, Koudstaal W, Kostense S, Havenga MJ, Truitt DM, Sumida SM, Kishko MG, Arthur JC, Korioth-Schmitz B, Newberg MH, Gorgone DA, Lifton MA, Panicali DL, Nabel GJ, Letvin NL, Goudsmit J. Immunogenicity of recombinant adenovirus serotype 35 vaccine in the presence of pre-existing anti-Ad5 immunity. J Immunol. 2004;172(10):6290–6297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boukhvalova MS, Prince GA, Blanco JC. Respiratory syncytial virus infects and abortively replicates in the lungs in spite of preexisting immunity. J Virol. 2007;81(17):9443–9450. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00102-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Murphy BR, Radl J, Haaijman JJ, Mestecky J. Subclass distribution and molecular form of immunoglobulin A hemagglutinin antibodies in sera and nasal secretions after experimental secondary infection with influenza A virus in humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;22(2):259–264. doi: 10.1128/jcm.22.2.259-264.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukreyev A, Collins PL. Filovirus vaccines: what challenges are left? Expert Rev Vaccines. 2010;9(1):5–8. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukreyev A, Lamirande EW, Buchholz UJ, Vogel LN, Elkins WR, St Claire M, Murphy BR, Subbarao K, Collins PL. Mucosal immunisation of African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) with an attenuated parainfluenza virus expressing the SARS coronavirus spike protein for the prevention of SARS. Lancet. 2004;363(9427):2122–2127. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16501-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukreyev A, Marzi A, Feldmann F, Zhang L, Yang L, Ward JM, Dorward DW, Pickles RJ, Murphy BR, Feldmann H, Collins PL. Chimeric human parainfluenza virus bearing the Ebola virus glycoprotein as the sole surface protein is immunogenic and highly protective against Ebola virus challenge. Virology. 2009;383(2):348–361. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukreyev A, Rollin PE, Tate MK, Yang L, Zaki SR, Shieh WJ, Murphy BR, Collins PL, Sanchez A. Successful topical respiratory tract immunization of primates against Ebola virus. J Virol. 2007;81(12):6379–6388. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00105-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukreyev A, Yang L, Zaki SR, Shieh WJ, Rollin PE, Murphy BR, Collins PL, Sanchez A. A single intranasal inoculation with a paramyxovirus-vectored vaccine protects guinea pigs against a lethal-dose Ebola virus challenge. J Virol. 2006;80(5):2267–2279. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.5.2267-2279.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burlington DB, Clements ML, Meiklejohn G, Phelan M, Murphy BR. Hemagglutinin-specific antibody responses in immunoglobulin G, A, and M isotypes as measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay after primary or secondary infection of humans with influenza A virus. Infect Immun. 1983;41(2):540–545. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.2.540-545.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casimiro DR, Chen L, Fu TM, Evans RK, Caulfield MJ, Davies ME, Tang A, Chen M, Huang L, Harris V, Freed DC, Wilson KA, Dubey S, Zhu DM, Nawrocki D, Mach H, Troutman R, Isopi L, Williams D, Hurni W, Xu Z, Smith JG, Wang S, Liu X, Guan L, Long R, Trigona W, Heidecker GJ, Perry HC, Persaud N, Toner TJ, Su Q, Liang X, Youil R, Chastain M, Bett AJ, Volkin DB, Emini EA, Shiver JW. Comparative immunogenicity in rhesus monkeys of DNA plasmid, recombinant vaccinia virus, and replication-defective adenovirus vectors expressing a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gag gene. J Virol. 2003;77(11):6305–6313. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6305-6313.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claassen EA, van der Kant PA, Rychnavska ZS, van Bleek GM, Easton AJ, van der Most RG. Activation and inactivation of antiviral CD8 T cell responses during murine pneumovirus infection. J Immunol. 2005;175(10):6597–6604. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PL, Crowe JEJ. Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Metapneumovirus. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Fields Virology. 5 ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 2007. pp. 1601–1646. 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Croyle MA, Patel A, Tran KN, Gray M, Zhang Y, Strong JE, Feldmann H, Kobinger GP. Nasal delivery of an adenovirus-based vaccine bypasses pre-existing immunity to the vaccine carrier and improves the immune response in mice. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(10):e3548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNapoli JM, Murphy BR, Collins PL, Bukreyev A. Impairment of the CD8+ T cell response in lungs following infection with human respiratory syncytial virus is specific to the anatomical site rather than the virus, antigen, or route of infection. Virol J. 2008;5:105. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinapoli JM, Nayak B, Yang L, Finneyfrock BW, Cook A, Andersen H, Torres-Velez F, Murphy BR, Samal SK, Collins PL, Bukreyev A. Newcastle disease virus-vectored vaccines expressing the hemagglutinin or neuraminidase protein of H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza virus protect against virus challenge in monkeys. J Virol. 2009 doi: 10.1128/JVI.01946-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbin AP, Skiadopoulos MH, McAuliffe JM, Riggs JM, Surman SR, Collins PL, Murphy BR. Human parainfluenza virus type 3 (PIV3)expressing the hemagglutinin protein of measles virus provides a potential method for immunization against measles virus and PIV3 in early infancy. J Virol. 2000;74(15):6821–6831. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.15.6821-6831.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez Bracho JG, Roldan Fernandez SG. Early reactions in pupils vaccinated with an aerosol measles vaccine. Salud Publica Mex. 1990;32(6):653–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-de Castro J, Kumate-Rodriguez J, Sepulveda J, Ramirez-Isunza JM, Valdespino-Gomez JL. Measles vaccination by the aerosol method in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. 1997;39(1):53–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton RB, Olson MR, Varga SM. Regulation of Cytokine Production by Virus-specific CD8 T Cells in the Lung. J Virol. 2008 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00840-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbutt M, Liebscher R, Wahl-Jensen V, Jones S, Moller P, Wagner R, Volchkov V, Klenk HD, Feldmann H, Stroher U. Properties of replication-competent vesicular stomatitis virus vectors expressing-glycoproteins of filoviruses and arenaviruses. J Virol. 2004;78(10):5458–5465. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.10.5458-5465.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisbert TW, Pushko P, Anderson K, Smith J, Davis KJ, Jahrling PB. Evaluation in nonhuman primates of vaccines against Ebola virus. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(5):503–507. doi: 10.3201/eid0805.010284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray PM, Arimilli S, Palmer EM, Parks GD, Alexander-Miller MA. Altered function in CD8+ T cells following paramyxovirus infection of the respiratory tract. J Virol. 2005;79(6):3339–3349. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3339-3349.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayson MH, Ramos MS, Rohlfing MM, Kitchens R, Wang HD, Gould A, Agapov E, Holtzman MJ. Controls for lung dendritic cell maturation and migration during respiratory viral infection. J Immunol. 2007;179(3):1438–1448. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson E, Jaax N, White J, Jahrling P. Lethal experimental infections of rhesus monkeys by aerosolized Ebola virus. Int J Exp Pathol. 1995;76(4):227–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SM, Feldmann H, Stroher U, Geisbert JB, Fernando L, Grolla A, Klenk HD, Sullivan NJ, Volchkov VE, Fritz EA, Daddario KM, Hensley LE, Jahrling PB, Geisbert TW. Live attenuated recombinant vaccine protects nonhuman primates against Ebola and Marburg viruses. Nat Med. 2005;11(7):786–790. doi: 10.1038/nm1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanesa-Thasan N, Smucny JJ, Hoke CH, Marks DH, Konishi E, Kurane I, Tang DB, Vaughn DW, Mason PW, Shope RE. Safety and immunogenicity of NYVAC-JEV and ALVAC-JEV attenuated recombinant Japanese encephalitis virus-poxvirus vaccines in vaccinia-nonimmune and vaccinia-immune humans. Vaccine. 2000;19(4–5):483–491. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00191-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karron RA, Belshe RB, Wright PF, Thumar B, Burns B, Newman F, Cannon JC, Thompson J, Tsai T, Paschalis M, Wu SL, Mitcho Y, Hackell J, Murphy BR, Tatem JM. A live human parainfluenza type 3 virus vaccine is attenuated and immunogenic in young infants. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(5):394–405. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000066244.31769.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karron RA, Collins PL. Parainfluenza Viruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Fields Virology. 5 ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 2007. p. 1. 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn JH. In: Filoviruses. 1 ed. Calisher CH, editor. Wien New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Legge KL, Braciale TJ. Accelerated migration of respiratory dendritic cells to the regional lymph nodes is limited to the early phase of pulmonary infection. Immunity. 2003;18(2):265–277. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemckert AA, Sumida SM, Holterman L, Vogels R, Truitt DM, Lynch DM, Nanda A, Ewald BA, Gorgone DA, Lifton MA, Goudsmit J, Havenga MJ, Barouch DH. Immunogenicity of heterologous prime-boost regimens involving recombinant adenovirus serotype 11 (Ad11) and Ad35 vaccine vectors in the presence of anti-ad5 immunity. J Virol. 2005;79(15):9694–9701. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.15.9694-9701.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukens MV, Kruijsen D, Coenjaerts FE, Kimpen JL, van Bleek GM. Respiratory syncytial virus-induced activation and migration of respiratory dendritic cells and subsequent antigen presentation in the lung-draining lymph node. J Virol. 2009;83(14):7235–7243. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00452-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy K, Tatsis N, Korioth-Schmitz B, Lasaro MO, Hensley SE, Lin SW, Li Y, Giles-Davis W, Cun A, Zhou D, Xiang Z, Letvin NL, Ertl HC. Effect of preexisting immunity to adenovirus human serotype 5 antigens on the immune responses of nonhuman primates to vaccine regimens based on human-or chimpanzee-derived adenovirus vectors. J Virol. 2007;81(12):6594–6604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02497-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LJ, Muench H. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez A, Geisbert TW, Feldmann H. Filoviridae: Marburg and Ebola Viruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Roizman B, Straus SE, editors. Fields Virology. 5 ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 2007. p. 1. 2 vols. [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe S, Polyanskaya N, Dennis M, Sutter G, Hanke T, Erfle V, Hirsch V, Cranage M. Induction of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-specific CTL in rhesus macaques by vaccination with modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing SIV transgenes: influence of pre-existing anti-vector immunity. J Gen Virol. 2001;82(Pt 9):2215–2223. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-9-2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan NJ, Martin JE, Graham BS, Nabel GJ. Correlates of protective immunity for Ebola vaccines: implications for regulatory approvalby the animal rule. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(5):393–400. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan NJ, Sanchez A, Rollin PE, Yang ZY, Nabel GJ. Development of a preventive vaccine for Ebola virus infection in primates. Nature. 2000;408(6812):605–609. doi: 10.1038/35046108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao T, Davoodi F, Cho CJ, Skiadopoulos MH, Durbin AP, Collins PL, Murphy BR. A live attenuated recombinant chimeric parainfluenza virus (PIV) candidate vaccine containing the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase and fusion glycoproteins of PIV1 and the remaining proteins from PIV3 induces resistance to PIV1 even in animals immune to PIV3. Vaccine. 2000;18(14):1359–1366. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallbracht S, Unsold H, Ehl S. Functional impairment of cytotoxic T cells in the lung airways following respiratory virus infections. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36(6):1434–1442. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wyke Coelingh KL, Winter C, Murphy BR. Antigenic variation in the hemagglutinin-neuraminidase protein of human parainfluenza type 3 virus. Virology. 1985;143(2):569–582. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90395-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Sanchez A, Ward JM, Murphy BR, Collins PL, Bukreyev A. A paramyxovirus-vectored intranasal vaccine against Ebola virus is immunogenic in vector-immune animals. Virology. 2008;377(2):255–264. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang ZY, Wyatt LS, Kong WP, Moodie Z, Moss B, Nabel GJ. Overcoming immunity to a viral vaccine by DNA priming before vector boosting. J Virol. 2003;77(1):799–803. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.799-803.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]