Abstract

As epitope mimics, mimotopes have been widely utilized in the study of epitope prediction and the development of new diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines. Screening the random peptide libraries constructed with phage display or any other surface display technologies provides an efficient and convenient approach to acquire mimotopes. However, target-unrelated peptides creep into mimotopes from time to time through binding to contaminants or other components of the screening system. In this study, we present SAROTUP, a free web tool for scanning, reporting and excluding possible target-unrelated peptides from real mimotopes. Preliminary tests show that SAROTUP is efficient and capable of improving the accuracy of mimotope-based epitope mapping. It is also helpful for the development of mimotope-based diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines.

1. Introduction

In 1985, Smith pioneered phage display technology, an in vitro methodology and system for presenting, selecting and evolving proteins and peptides displayed on the surface of phage virion [1]. Since then, phage display has developed rapidly and become an increasingly popular tool for both basic research such as the exploration of protein-protein interaction networks and sites [2–4], and applied research such as the development of new diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines [5–10]. Usually, the protein used to screen the phage display library is termed as target and the genuine partner binding to the target is called template. Peptide mimicking the binding site on the template and binding to the target is defined as mimotope, which was first introduced by Geysen et al. [11]. One type of the most frequently used targets is monoclonal antibody. In this situation, the template is the corresponding antigen inducing the antibody, and the mimotope is a mimic of the genuine epitope. In fact, the original definition of mimotope given by Geysen et al. goes “A mimotope is defined as a molecule able to bind to the antigen combining site of an antibody molecule, not necessarily identical with the epitope inducing the antibody, but an acceptable mimic of the essential features of the epitope [11].” Mimotopes and the corresponding epitope are considered to have similar physicochemical properties and spatial organization. The mimicry between mimotopes and genuine epitope makes mimotopes reasonable solutions to epitope mapping, network inferring, and new diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines developing.

Powered by phage display technology, mimotopes can be acquired in a relatively cheap, efficient and convenient way, that is, screening phage-displayed random peptides libraries with a given target. However, not all phages selected out are target-specific, because the target itself is only one component of the screening system [12]. From time to time, phages reacting with contaminants in the target sample or other components of the screening system such as the solid phase (e.g., plastic plates) and the capturing molecule (e.g., streptavidin, secondary antibody) rather than binding to the actual target are recovered with those target-specific binders (displaying mimotopes) during the rounds of panning. Peptides displayed on these phages are called target-unrelated peptides (TUP), a term coined recently by Menendez and Scott in a review [12].

The results from phage display technology might be a mixture of target-unrelated peptides and mimotopes, and it can be difficult to discriminate TUP from mimotopes since the binding assays used to confirm the affinity of peptides for the target often employ the same components as the initial panning experiment [12]. Therefore, target-unrelated peptides might be taken into study as mimotopes if the researchers are not careful enough. Undoubtedly, this will make the conclusion of the study dubious. Several such examples have been discussed in references [12, 13]. Obviously, target-unrelated peptides are not appropriate candidates for the development of new diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines. For mimotope-based epitope mapping, target-unrelated peptides are main noise. If TUP is included in the mapping, the input data is improper and the result might be misleading [14]. There are now quite a few programs for mimotope based epitope mapping, none of them, however, has a procedure to scan, report and exclude target-unrelated peptides [15–23].

In this study, we describe a web server named SAROTUP, which is an acronym for “Scanner And Reporter Of Target-Unrelated Peptides”. SAROTUP was coded with Perl as a CGI program and can be freely accessed and used to scan peptides acquired from phage display technology. It is capable of finding, reporting, and precluding possible target-unrelated peptides, which is very helpful for the development of mimotope-based diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines. The power and efficiency of SAROTUP was also demonstrated by preliminary tests in the present study.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Compilation of TUP Motifs

Recently, Menendez and Scott reviewed a collection of target-unrelated peptides recovered in the screening of phage-displayed random peptide libraries with antibodies [12]. They divided their collection into several categories according to the component of the screening system to which target-unrelated peptides bind. They also derived one or more TUP motifs for each category. Very recently, Brammer et al. reported a completely new type of target-unrelated peptides [13]. In the review of Menendez and Scott, target-unrelated selection is due to the binding to contaminants or components other than target; however, in the report of Brammer et al., target-unrelated selection is due to a coincident point mutation in the phage library [12, 13]. We compiled a set of 23 TUP motifs from the above two references [12, 13], including 12 motifs specific for the capturing agents, 5 motifs specific for the constant region of antibody, 3 motifs specific for the screening solid phase, 2 motifs specific for the contaminants in the target sample, and 1 motif for a mutation in phage library (Table 1). All motifs are presented in patterns according to Prosite format [24].

Table 1.

Known patterns of target-unrelated peptides.

| TUP Category | TUP Pattern | Mechanism in brief |

|---|---|---|

| Capturing agents | H-P-[QM], G-D-[WF]-x-F, W-x-W-L, E-P- | Binding to streptavidin |

| D-W-[FY], D-V-E-x-W-[LIV] | ||

| W-x-P-P-F-[RK] | Binding to biotin | |

| W-[TS]-[LI]-x(2)-H-[RK] | Binding to Protein A | |

| R-T-[LI]-[TS]-K-P, [LFW]-x-F-Q, W-I-S- | Binding to secondary antibody | |

| x(2)-D-W, Q-[LV]-[LV]-Q, RTYK | ||

| Constant region of antibody (the target) | S-S-[IL], GELVW, G-[LI]-T-D-[WY], | Binding to the Fc fragment |

| [RHK]-P-S-P, P-S-P-[RK] | ||

| Screening solid phase | W-x(2)-W, WHWRLPS, F-H-x(2)-W | Binding to plastic |

| Contaminants in the target sample | F-H-E-x-W-P-[ST] | Binding to contaminant bovine serum albumin |

| QSYP | Binding to contaminant bovine IgG | |

| Phage mutation | HAIYPRH | Growing faster than other phages |

2.2. Implementation of SAROTUP

The SAROTUP was implemented as a free online service, powered by Apache and Perl. Three pages are designed and integrated into a tabbed web interface with cascading style sheets codes. The core program of SAROTUP was sar.pl, a CGI script coded with Perl. In this script, the 23 TUP motifs were converted to regular expressions, which were then used to match each input peptide sequence.

2.3. Construction of Test Data Sets

We constructed two-test data sets from [12, 13, 15–23, 25, 26]. The first data set contains 8 cases; 6 of them are sourced from test cases used in extant programs for mimotope-based epitope mapping [15–23]; the left 2 are cases studies published recently [25, 26]. As shown in Table 2, the target of each case in the first data set is monoclonal antibody and the structure of corresponding antigen-antibody complex has been resolved, which is used to derive its structural epitope as the golden standard for evaluation. For each case, there is one or more sets of peptides recovered from phage display technology. These peptides have been used in mimotope-based epitope mapping by other researchers. We scanned each set of peptides with SAROTUP. If target-unrelated peptides were found, a new panel of peptides excluding TUP was produced. The old and the new panel of peptides were then used to predict epitope using Mapitope or PepSurf [15, 21, 22]. Finally, the results were compared to show if SAROTUP could improve the performance of mimotope-based epitope mapping.

Table 2.

A summary of the first test data set for SAROTUP.

| Target | Template | Complex | Peptides | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17b | HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein (gp120) | 1GC1 | 11 | [15] |

| trastuzumab | human receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2 (HER2) | 1N8Z | 5 | [20] |

| 82D6A3 | human von Willebrand factor (vWF) | 2ADF | 5 | [19] |

| 13b5 | HIV-1 capsid protein p24 | 1E6J | 14 | [15] |

| BO2C11 | human coagulation factor VIII | 1IQD | 27 | [19] |

| cetuximab | human epidermal growth factor receptor | 1YY9 | 4 | [20] |

| 80R | SARS-coronavirus spike protein S1 | 2GHW | 42 + 18 | [26] |

| b12 | HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein (gp120) | 2NY7 | 2 + 32 + 19 | [25] |

The second data set is composed of 100 peptides in raw sequence format. It has two groups. The first group has 77 sequences compiled from the first data set without any known TUP motifs; the second group has 23 sequences sourced from [12, 13] with various TUP motifs. The mixture of the two groups of sequences made the second data set, which was then used as the sample input and can be used to evaluate the efficiency of SAROTUP.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Web Interface of SAROTUP

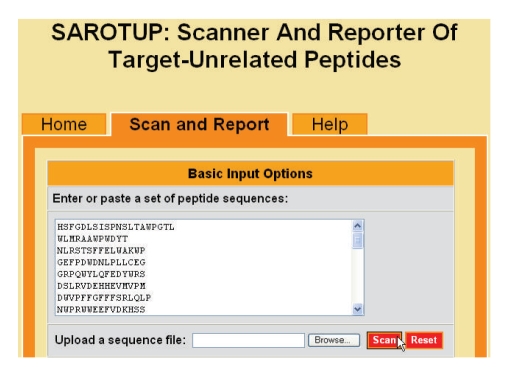

As a free online service, the web interface of SAROTUP has successfully been implemented as a tabbed web page. The left tab is the default page, providing a brief introduction to this web service. The right tab is a more detailed help page. Click the middle tab will display a web form. The upper section of the form is for basic input (Figure 1). The users can either paste a set of peptide sequences in the text box or upload a sequence file to the SAROTUP server for scanning. As shown in Figure 1, a panel of peptides in raw sequence format taken from the b12 test case was pasted in the text box. Besides the raw sequences, SAROTUP also supports peptides in FASTA format. However, only the standard IUPAC one-letter amino acid codes are accepted at present.

Figure 1.

Snapshot of the upper section of SAROTUP.

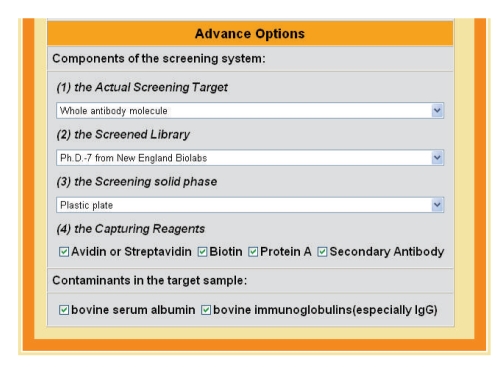

The lower section of the form has a series of options (Figure 2). It includes three drop lists for the screening target, screened library, and screening solid phase, respectively. It also has two groups of check boxes for the capturing reagents and contaminants in the target sample or screening system. By default, SAROTUP will scan each peptide against all the known 23 TUP motifs. However, the users can customize their scan according to their experiment at this section.

Figure 2.

Snapshot of the lower section of SAROTUP.

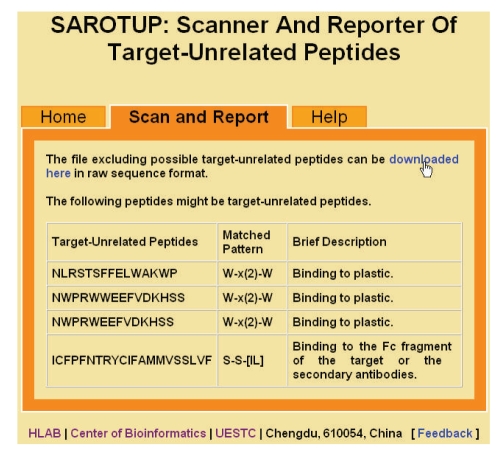

After the users submit their request, the scanning results of SAROTUP will be displayed on the middle tabbed page. If any target-unrelated peptides are found, they will be reported in a table. At the same time, a new panel of peptides excluding target-unrelated peptides is produced and can be downloaded from the hyperlink created by the SAROTUP server (Figure 3). The file of the new panel of peptides will be stored on the server for a month and then automatically deleted.

Figure 3.

Snapshot of SAROTUP result page. Target-unrelated peptides in the b12 test case are reported in the table. The new panel of peptides excluding the target-unrelated peptides can be downloaded from the hyperlink.

We have tested SAROTUP on the Internet Explorer (version 6.0), Mozilla Firefox (version 3.5.2), and Google Chrome (version 3.0). Although SAROTUP looks a little bit different among different browsers, it works normally on all browsers tested.

3.2. Power of SAROTUP

As shown in Table 2, the first test data set has 11 panels of peptides acquired from phage display libraries screened with 8 targets. In the 11 panels of peptides SAROTUP scanned, there were target-unrelated peptides in 3 panels from cetuximab, 80R, and b12 test case, respectively (Table 3). This result suggested it was not rare that target-unrelated peptides sneaked into biopanning results and then were taken as mimotopes in study. In all, 7 target-unrelated peptides were found; 4 of them were due to binding to plastic; the left 3 were due to binding to the Fc fragment (Table 3).

Table 3.

Target-unrelated peptides in the first test data set.

| Target | Target-unrelated peptides | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| cetuximab | VWQRWQKSYV | Binding to plastic |

| 80R | CESSLCLMYSLGPPA, | Binding to the Fc fragment |

| YSTPSSILDTHPLYK | Binding to the Fc fragment | |

| b12 | NLRSTSFFELWAKWP | Binding to plastic |

| NWPRWWEEFVDKHSS | Binding to plastic | |

| NWPRWEEFVDKHSS | Binding to plastic | |

| ICFPFNTRYCIFAMMVSSLVF | Binding to the Fc fragment | |

For the above 3 cases, the genuine epitopes recognized by cetuximab, 80R, and b12 monoclonal antibodies are compiled according to the CED records [27] and PDBsum entries[28]. Mapitope or PepSurf [15, 21, 22] were used to perform mimotope-based epitope prediction with or without SAROTUP procedure. For Mapitope and PepSurf algorithm, the library type was set to “random”; the stop codon modification was set to “none”; and all other options were in default. The cluster with best score was taken as the predicted epitope. In the cetuximab case, PepSurf was used because there are only four or three peptides in the panel, statistically too few for Mapitope. In the case of 80R and b12, Mapitope was used because many peptides in the two cases exceeding the length limit of PepSurf, that is, 14 amino acids. If a predicted residue is identical with a residue in the true epitope, it is underlined (Table 4).

Table 4.

Mimotope-based epitope prediction with or without SAROTUP procedure.

| Target | Prediction without SAROTUP procedure | Genuine epitope | Prediction with SAROTUP procedure |

|---|---|---|---|

| cetuximab | N134, E136, S137, I138, Q139, W140, R141, Q164, K185, L186, T187, K188 | P349, R353, L382, Q384, Q408, H409, Q411, F412, V417, S418, I438, S440, G441, K443, K465, I467, S468, N469, G471, N473 | K375, I401, R403, R405, T406, K407, Q408, H409, G410, Q411, F412, D436 |

| 80R | H445, V458, P459, F460, S461, P462, D463, G464, K465, P466, C467, T468, P469, P470, A471, L472, N473, C474, Y475 | R426, S432, Y436, K439, Y440, Y442, P469, P470, A471, L472, C474, Y475, W476, L478, N479, D480, G482, Y484, T485, T486, T487, G488,Y491, Q492 | L443, R444, H445, I455, S456, N457, V458, P459, F460, S461, P462, D463, G464, K465, P466, C467, T468, P469, P470, A471, L472, N473, C474, Y475 |

| b12 | I108, C109, S110, L111, D113, Q114, S115, L116, K117, P118, C119, V120, P206, K207, V208, S209, F210, E211, P212, I213, P214, I251, R252, P253, I424, N425, M426, W427, C428, K429, V430 | N280, A281, S365, G366, G367, D368, P369, I371, V372, T373, Y384, N386, P417, R419, V430, G431, K432, T455, R456, G472, G473, D474, M475 | W95, T232, F233, N234, T236, S257, L260, N262, G263, S264, L265, A266, E267, E268, E269, V270, V271, T290, S291, S364, S365, G366, G367, D368, P369, E370, I371, V372, T373, T450, S481 |

As shown in Table 4, the number of true positives improved from zero to four in the cetuximab case with SAROTUP procedure. When it came to the b12 case, the number of true positives increased from one to eight. SAROTUP did not improve the number of true positives in the 80R case when the parameters are same to the cetuximab and b12 cases. However, when the distance parameter was adjusted from default (i.e., 9 Å) to 10 Å, SAROTUP did increase the number of true positive residues from eight to eleven. These results indicate: (1) epitope prediction based on mimotope will be interfered if target-unrelated peptides are taken as mimotopes; (2) SAROTUP can improve the performance of mimotope based epitope mapping through cleaning the input data.

We also scanned the second data set to evaluate the efficiency of SAROTUP. The second data set has 100 peptides, varying from 6 to 22 residues long. Suppose that matching each pattern to each peptide manually costs 10 seconds, then it would take a researcher more than 6 hours (23,000 seconds) to look through the second data set for target-unrelated peptides, even if he is as prompt during the whole period. However, it took only one second for SAROTUP to complete this work. Besides, a table of target-unrelated peptides and a new panel of peptides excluding TUP was produced at the same time by SAROTUP. It is true that some target-unrelated peptides can be identified through control and binding competition experiments. However, using SAROTUP first will certainly save a lot of labor, money, and time for researchers in this area.

3.3. Extending of SAROTUP

Although the target of all tests described previously were monoclonal antibodies, SAROTUP can be customized and used in scanning the results from phage display technology using other targets such as enzymes and receptors. This is because their screening systems are similar. For the same reason, we can also expect that SAROTUP will extend its use to other similar in vitro evolution techniques, such as ribosome display [29–31], yeast display [32], and bacterial display [33–35].

Furthermore, SAROTUP will not only benefit the mimotope-based epitope mapping, but also the development of new diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines. Target-unrelated peptides are not appropriate candidates for mimotope based diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines, since they are mimics to components or contaminants of the screening system rather than target. Therefore, it is reasonable to find and exclude possible target-unrelated peptides from the candidate list of new diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines. Take the cetuximab as an example. Riemer et al. screened a phage-displayed random peptides library with the cetuximab and got four different peptides, that is, QFDLSTRRLK, QYNLSSRALK, VWQRWQKSYV, and MWDRFSRWYK [36]. As described previously, we scanned the four “mimotopes” with SAROTUP and the result suggested that the peptide VWQRWQKSYV might be a TUP. Indeed, the dot blot analysis of Riemer et al. showed that QYNLSSRALK bound the cetuximab with high affinity but VWQRWQKSYV was less reactive with the cetuximab [36]. Trying to develop a mimotope vaccine, Riemer et al. synthesized two-vaccine constructs with the peptide QYNLSSRALK and VWQRWQKSYV, respectively. After immunization mice with these constructs, they found that either the cetuximab or the antibodies induced by the QYNLSSRALK vaccine construct inhibited the growth of A431 cancer cells significantly. The inhibition of the antibodies induced by the VWQRWQKSYV vaccine construct however, was not statistically significant when compared with the inhibition caused by the isotype control antibody [36].

3.4. Cautions in Using SAROTUP

SAROTUP must be used with caution since it is a tool only based on pattern matching at present. There are a lot of target-unrelated peptides bearing no known motifs [12]. As these TUPs are not embedded in SAROTUP at present, it is possible that a true TUP cannot be detected by SAROTUP. To reduce this kind of false negatives, we are constructing a database for target-unrelated peptides and mimotopes. Besides the motif-based search, the database-based search can find out the known TUP without known motifs.

It is also possible that a SAROTUP predicted target unrelated peptide is actually target-specific. To decrease this kind of false positives, the users should customize the scan according to their experiment at the section of advance options. For example, the user should select “antibody without Fc fragment” as the target if Fab was used in biopanning; this will prevent SAROTUP from reporting peptides bearing the Fc-binding motifs as TUP. As described above, SAROTUP in future will also provide an exact match tool based on database search. In this way, a match might mean that different research groups have isolated the same peptide with a variety of targets. It is obvious that this peptide can hardly be a true target binder. Thus, the false positive rate of SAROTUP can be decreased further when its new feature become available.

At last, we must point out that the controlled experiment is still the gold standard to distinguish TUPs from the specific mimotopes. The report of SAROTUP should be verified with experiment.

4. Conclusions

SAROTUP, a web application for scanning, reporting and excluding target-unrelated peptides has been coded with Perl. It helps researchers to predict epitope more accurately based on mimotopes. It is also useful in the development of diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccines. To our knowledge, SAROTUP is the first web tool for TUP detecting and data cleaning. It is very convenient for the community to access SAROTUP through http://immunet.cn/sarotup/.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions and comments, which have led to the improvement of this paper. This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under the Grant 30600138 and the Scientific Research Foundation of UESTC for Youth under the Grant JX0769.

References

- 1.Smith GP. Filamentous fusion phage: novel expression vectors that display cloned antigens on the virion surface. Science. 1985;228(4705):1315–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.4001944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scott JK, Smith GP. Searching for peptide ligands with an epitope library. Science. 1990;249(4967):386–390. doi: 10.1126/science.1696028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong AHY, Drees B, Nardelli G, et al. A combined experimental and computational strategy to define protein interaction networks for peptide recognition modules. Science. 2002;295(5553):321–324. doi: 10.1126/science.1064987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thom G, Cockroft AC, Buchanan AG, et al. Probing a protein-protein interaction by in vitro evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103(20):7619–7624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602341103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang LF, Yu M. Epitope identification and discovery using phage display libraries: applications in vaccine development and diagnostics. Current Drug Targets. 2004;5(1):1–15. doi: 10.2174/1389450043490668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Riemer AB, Jensen-Jarolim E. Mimotope vaccines: epitope mimics induce anti-cancer antibodies. Immunology Letters. 2007;113(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petrenko VA. Evolution of phage display: from bioactive peptides to bioselective nanomaterials. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. 2008;5(8):825–836. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.8.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao L, Liu Z, Fan D. Overview of mimotopes and related strategies in tumor vaccine development. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2008;7(10):1547–1555. doi: 10.1586/14760584.7.10.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thie H, Meyer T, Schirrmann T, Hust M, Dubel S. Phage display derived therapeutic antibodies. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 2008;9(6):439–446. doi: 10.2174/138920108786786349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Knittelfelder R, Riemer AB, Jensen-Jarolim E. Mimotope vaccination—from allergy to cancer. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2009;9(4):493–506. doi: 10.1517/14712590902870386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geysen HM, Rodda SJ, Mason TJ. A priori delineation of a peptide which mimics a discontinuous antigenic determinant. Molecular Immunology. 1986;23(7):709–715. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(86)90081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Menendez A, Scott JK. The nature of target-unrelated peptides recovered in the screening of phage-displayed random peptide libraries with antibodies. Analytical Biochemistry. 2005;336(2):145–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brammer LA, Bolduc B, Kass JL, Felice KM, Noren CJ, Hall MF. A target-unrelated peptide in an M13 phage display library traced to an advantageous mutation in the gene II ribosome-binding site. Analytical Biochemistry. 2007;373(1):88–98. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J, Xia M, Lin H, Guo F. Information loss and noise inclusion risk in mimotope based epitope mapping. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Engineering (iCBBE ’09); 2009; Beijing, China. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enshell-Seijffers D, Denisov D, Groisman B, et al. The mapping and reconstitution of a conformational discontinuous B-cell epitope of HIV-1. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2003;334(1):87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mumey BM, Bailey BW, Kirkpatrick B, Jesaitis AJ, Angel T, Dratz EA. A new method for mapping discontinuous antibody epitopes to reveal structural features of proteins. Journal of Computational Biology. 2003;10(3-4):555–567. doi: 10.1089/10665270360688183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halperin I, Wolfson H, Nussinov R. SiteLight: binding-site prediction using phage display libraries. Protein Science. 2003;12(7):1344–1359. doi: 10.1110/ps.0237103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schreiber A, Humbert M, Benz A, Dietrich U. 3D-Epitope-Explorer (3DEX): localization of conformational epitopes within three-dimensional structures of proteins. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2005;26(9):879–887. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreau V, Granier C, Villard S, Laune D, Molina F. Discontinuous epitope prediction based on mimotope analysis. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(9):1088–1095. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang J, Gutteridge A, Honda W, Kanehisa M. MIMOX: a web tool for phage display based epitope mapping. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7, article 451 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayrose I, Shlomi T, Rubinstein ND, et al. Epitope mapping using combinatorial phage-display libraries: a graph-based algorithm. Nucleic Acids Research. 2007;35(1):69–78. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayrose I, Penn O, Erez E, et al. Pepitope: epitope mapping from affinity-selected peptides. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(23):3244–3246. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang YX, Bao YL, Guo SY, Wang Y, Zhou CG, Li YX. Pep-3D-search: a method for B-cell epitope prediction based on mimotope analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9, article 538 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hulo N, Bairoch A, Bulliard V, Cerutti L, et al. The 20 years of PROSITE. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36, database issue:D245–D249. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bublil EM, Yeger-Azuz S, Gershoni JM. Computational prediction of the cross-reactive neutralizing epitope corresponding to the monoclonal antibody b12 specific for HIV-1 gp120. FASEB Journal. 2006;20(11):1762–1774. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5509rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarnovitski N, Matthews LJ, Sui J, Gershoni JM, Marasco WA. Mapping a neutralizing epitope on the SARS coronavirus spike protein: computational prediction based on affinity-selected peptides. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2006;359(1):190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang J, Honda W. CED: a conformational epitope database. BMC Immunology. 2006;7, article 7 doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laskowski RA. PDBsum new things. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37, database issue:D355–D359. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts RW, Szostak JW. RNA-peptide fusions for the in vitro selection of peptides and proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(23):12297–12302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gold L. mRNA display: diversity matters during in vitro selection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(9):4825–4826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091101698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipovsek D, Pluckthun A. In-vitro protein evolution by ribosome display and mRNA display. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2004;290(1-2):51–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boder ET, Wittrup KD. Yeast surface display for screening combinatorial polypeptide libraries. Nature Biotechnology. 1997;15(6):553–557. doi: 10.1038/nbt0697-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stahl S, Uhlen M. Bacterial surface display: trends and progress. Trends in Biotechnology. 1997;15(5):185–192. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(97)01034-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Georgiern G, Stathopoulos C, Daugherty PS, Nayak AR, Iverson BL, Curtiss R., III Display of heterologous proteins on the surface of microorganisms: from the screening of combinatorial libraries to live recombinant vaccines. Nature Biotechnology. 1997;15(1):29–34. doi: 10.1038/nbt0197-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samuelson P, Gunneriusson E, Nygren PA, Stahl S. Display of proteins on bacteria. Journal of Biotechnology. 2002;96(2):129–154. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(02)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riemer AB, Kurz H, Klinger M, Scheiner O, Zielinski CC, Jensen-Jarolim E. Vaccination with cetuximab mimotopes and biological properties of induced anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibodies. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97(22):1663–1670. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]