Abstract

The purpose of this double-blind, randomized, outpatient study was to evaluate the reinforcing and subjective effects of modafinil (200, 400, or 600 mg) in cocaine-abusers. Twelve participants (2 Female, 10 Male) completed this study, consisting of 3 blocks of 7 sessions; each block tested a difference dose of modafinil. During the first 2 sessions of each block, participants “sampled” 1 of the doses of modafinil, and placebo. This dose of modafinil and placebo were available for the subsequent five choice sessions of the block. In each choice session, participants had an opportunity to administer active or placebo capsules. Modafinil administration did not differ from placebo administration, and subjective-effects ratings were not systematically altered as a function of modafinil dose. Results suggest that modafinil does not have abuse liability in cocaine abusers.

Keywords: modafinil, human, cocaine

1. Introduction

Modafinil, a drug with many sites of action (Dackis and O’Brien, 2003; Karilla et al., 2008; Myrick et al., 2004), has been approved for the treatment of sleep disorders, including narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, and shift work. Modafinil has also been considered for off-label indications involving fatigue, for example, depression (Lam et al., 2007), multiple sclerosis (Lange et al., 2009), and cancer (Blackhall et al., 2009). It has also been used for the treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (Biederman et al., 2006; Pataki et al., 2004). The efficacy of modafinil as a medication for cocaine abuse is under investigation.

Modafinil (200–800 mg) has been safely co-administered with cocaine and decreased (Hart et al., 2008) or had no effect on cardiovascular effects (Dackis et al., 2003; Malcolm et al., 2002; 2006). Modafinil treatment (400 mg) increased cocaine-negative urines and periods of cocaine abstinence (Dackis et al., 2005), and decreased ratings of amphetamine-like qualities and high (200–800 mg: Dackis et al., 2003; Malcolm et al., 2006). Finally, in the laboratory, daily doses of modafinil (200, 400 mg) reduced self-administration of smoked cocaine (25 mg and 50 mg) in cocaine-dependent individuals (Hart et al., 2007).

It has been suggested that modafinil does not have abuse potential in humans using cocaine because it was not identified as cocaine-like (Rush et al., 2002a; 2002b) or asamphetamine-like (Jasinki, 2000) using a drug discrimination procedure. However, in females, it was identified as amphetamine-like, and, at 800 mg, produced a euphoric effect (Jasinski and Kovačević-Ristanović, 2000, data referred to but not shown). Modafinil was not reinforcing in a group of naïve rats (Deroche-Gamonet et al., 2002), but produced reinforcing effects in monkeys and some cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects in rats (Gold and Balster, 1996). Although the complete mechanisms of action of modafinil are unknown, evidence that modafinil interacts with the dopamine transporters has been accumulating (Madras et al., 2006; Zolkowska et al., 2009). A recent study hypothesized that because modafinil increased levels of striatal dopamine, it may have potential for abuse (Volkow et al., 2009a), possibly limiting its use for the treatment of cocaine abuse. Therefore, in this study we directly evaluated whether cocaine-abusing individuals, under controlled laboratory conditions, would self-administer modafinil or placebo.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Twelve non-treatment seeking cocaine-abusing participants (2F, 10M; 11 Black, 1 White) with an average age of 39 (SD=6) years completed this 7-week outpatient study. Participants were included if their average use of smoked cocaine was at least two times per week for the 6 months prior to study entry, and if they had given a cocaine-positive urine specimen during the screening process. Participants reported spending an average of $298 per week (/week) on cocaine (SD=$110) and using cocaine an average of 4.3 times/week (SD=1.5). Smoking was the primary route of cocaine administration. Other regular drug use included alcohol (M= 2 drinks/week, SD= 2 drinks/week) and tobacco cigarettes (M=9 cigarettes/day, SD=6 cigarettes/day). One participant reported spending approximately $25/week on marijuana, and one participant reported occasional marijuana, MDMA and Vicodin® use.

Prior to study onset, participants were told that the objective of the study was to assess the effects of potential medications to treat cocaine dependence. Detailed drug and medical histories were obtained, participants subsequently received complete medical and psychiatric evaluations, and signed consent forms. Outside drug use was monitored at each visit by urine toxicologies. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

2.2. Design

Three doses of modafinil (200, 400, 600 mg) and placebo were tested in separate blocks of 7 laboratory visits or sessions each, for a total of 21 sessions. Each block tested one dose of modafinil. Blocks consisted of two “sample” sessions, where participants received one active and one placebo modafinil dose (distinguished by capsule color), and 5 choice sessions, where participants selected between the two options. Both dose order, and order of sample presentation within dose, were randomized. Subjective effects were measured at baseline, one hour after (+1), and 4 hours after (+4) capsules were taken. Visual Analogue Scales (VAS) and the Drug Effect Questionnaire (DEQ) were completed at Sample and Choice visits.

2.3. Procedure

Laboratory sessions were conducted Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Upon arrival to the laboratory, breath alcohol levels were analyzed, blood pressure and heart rate were recorded, and urine toxicology analyses were performed. If a urine sample was positive for any substance other than cocaine or marijuana (permissible due to the long half-life), participation was not allowed for that day in order to avoid residual effects. A urine pregnancy test was conducted every other week in women. Participants then completed the baseline subjective-effects ratings, and were given a small standardized breakfast (juice, cereal or bagel or egg sandwich) immediately before taking the study medication. After taking the study medication, participants were monitored in the laboratory for an hour. They subsequently completed a second subjective-effects battery and a field sobriety test before leaving the laboratory. Participants were given a third subjective-effects battery (paper version) to complete 4 hours after taking the study medication and asked to return this battery at the next visit; they were also asked to call the laboratory 4 hours after taking the study medication to report on the degree of subjective effects they were feeling at that time. They were instructed to refrain from driving or operating heavy machinery for the remainder of the day, and were paid for their participation.

2.4. Drug

Two-hundred mg modafinil tablets were obtained from Cephalon Pharmaceuticals and were repackaged by the Pharmacy of the New York State Psychiatric Institute. Tablets were placed into different colored #00 capsules and lactose filler was added if necessary. Placebo capsules consisted of white lactose powder. Three capsules were taken at each visit to ensure the double-blind, e.g., one 200 mg capsule, two placebo capsules; two 200 mg capsules, one placebo capsule; three 200 mg capsules, or three placebo capsules.

2.5. Data analysis

The number of choices for modafinil or placebo made during the Choice Sessions was analyzed by a paired t-test within each modafinil dose. Subjective-effects data from Sample Sessions were examined and described with Cochran’s Q (DEQ) and Repeated Measures ANOVA (VAS). Repeated measures ANOVA models included Drug (2) Dose (3) and Time (3). Type I and Type II errors were of concern, thus, planned contrasts comparing +1 hr and +4 hr ratings to baseline (BL), and active to placebo ratings were examined, yet were only considered significant at p ≤ 0.01.

One percent of the data points were missing from the VAS due to computer error and +4 hour forms not being returned. Data were imputed using either last observation carried forward if the +4 hr point were missing, or averaging between BL and the +4 hr measurement if the +1 hr point were missing. One data point was missing at BL and a 0 value was imputed because the +1 hr value was also 0. Four percent of data were missing from the DEQ. Data were not imputed because the items of the DEQ are discrete variables, and proportional models were used for analysis. Data were analyzed using SPSS v. 16.0.2 for Windows and SuperANOVA v.1.11 for Macintosh.

3. Results

There were no differences between the number of choices for modafinil or placebo, as depicted in Figure 1. When considering these data as a function of number of participants who chose modafinil more than 3 times at any of the 3 doses, there were also no differences. In keeping with this finding, there were no systematic effects of modafinil on the VAS. Main effects of time revealed increases (“Bad Drug,” “Confused,” “Good Drug,” “High Quality,” “Liked Choice,” “Potent,” “Want Heroin,” “Would Pay,” “High”), or decreases (“Hunger,” “Confident”) over the course of the four-hour data collection period regardless of drug or dose.

Figure 1.

Average number of choices for placebo and modafinil as a function of modafinil dose. There were no differences between placebo and modafinil.

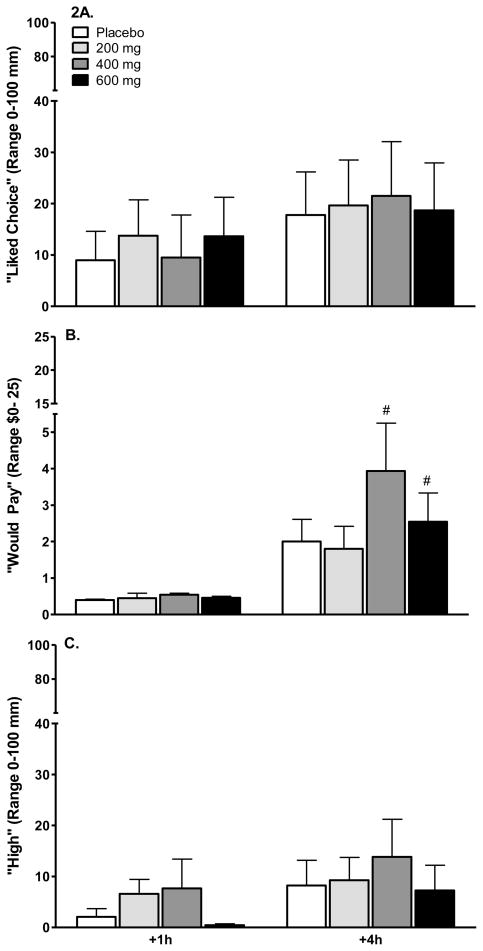

Although VAS scales ranged from 0–100 mm (other than “Would Pay,” which ranged from $0–$25), the largest difference over the 4 hour period spanned approximately 19 mm (“Liked Choice”), followed by 15 mm (“Good Drug Effect”), and 10 mm (“Potent”). All other time main effects were < 10 mm. Participants indicated they would pay less than $5 for modafinil. Figure 2, depicting “Liked Choice,” “Would pay,” and “High,” illustrates these modest effects.

Figure 2.

Figure 2A. VAS “Liked Choice” as a function of drug, modafinil dose, and time. There were no differences between placebo and modafinil.

Figure 2B. VAS “Would Pay” as a function of drug, modafinil dose, and time. There were no differences between placebo and modafinil. # indicates a +1 hr vs. +4 hr difference in mm, p ≤ 0.01.

Figure 2C. Ratings (mm) of VAS “High” as a function of drug, modafinil dose, and time. There were no differences between placebo and modafinil.

DEQ ratings indicated that the majority of participants would be “Not at all” or “A little” willing to take the drug again. In fact, combined ratings of these two items were equal to or greater than 70% of participants’ total ratings at all time points except +1 hour after participants took the 600 mg dose of modafinil (66%). When participants were asked to select which drug modafinil was most like, the majority indicated placebo. Cochran’s Q analyses revealed there were no differences between active and placebo ratings. When taken together, these data indicate that, although some participants rated modafinil favorably, the positive effects were not robust enough to engender drug administration.

4. Discussion

Data from the present investigation show that modafinil did not produce reinforcing effects as measured using self-administration procedures in this sample of cocaine abusers: modafinil was chosen at the same frequency as placebo. Consistent with the choice data, modafinil, in a dose range that extends up to 3 times the standard prescribed dose for narcolepsy, did not engender any “positive” subjective effects.

These data are consistent with studies that have approached this question employing different methodologies. Patients did not abuse modafinil during a carefully conducted clinical trial (Dackis et al., 2005). Modafinil was described by participants as being devoid of any psychoactive effects after acute administration (Rush et al., 2002a). Other reviews have also supported limited abuse potential of this drug (Malcolm et al., 2002; Myrick et al., 2004).

This is not to say that modafinil is without stimulant effects. When considered in the context of drug discrimination, 600 mg modafinil fully substituted for cocaine in half of the participants tested, yet overall, there was only 55% cocaine-appropriate responding (Rush et al., 2002b). Both 200 mg and 800 mg modafinil were identified as amphetamine-like, and 800 mg produced a significant response on the Morphine-Benzedrine Group scale from the Addiction Research Center Inventory in women (Jasinski and Kovačević-Ristanović, 2000, data referred to, but not shown). Similarly, high doses of modafinil substituted for cocaine in 67% of rats, and maintained responding in rhesus monkeys (Gold and Balster, 1996).

However, the magnitude of the subjective effects ratings elicited by modafinil compared to those for other drugs of abuse, such as cocaine or heroin, support the notion of limited abuse potential. Small doses of cocaine typically elicit ratings of “High” in the 30–40 mm range, while larger doses often elicit ratings in the 50–70 mm range (Foltin and Fischman, 1992; Foltin et al., 2003). Similarly, ratings of “High” for heroin range from 20–60 mm (Comer et al., 2008). The highest average rating “High” for modafinil was substantially lower at 13.8 mm.

Volkow et al. (2009) concluded that modafinil may have the potential for abuse because administration in healthy male volunteers led to increased dopaminergic activity in the nucleus accumbens. However, despite these neuroimaging findings, our behavioral data do not support this conclusion. Reinforcing effects of a drug are determined by both mechanism of action and rate of onset (Balster and Schuster, 1973; Abreu et al., 2001; Samaha et al., 2004, Volkow et al., 2009b). Our data reveal a gradual onset of effect over 4 hours, which does not coincide with a profile of substantial abuse liability. Neither 200 mg nor 400 mg oral modafinil were administered by the oral route any differently than placebo in this paradigm. Thus, even if these doses increased dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens, this effect is not associated with a preference for modafinil over placebo. Whether this would be the case if modafinil were abused by intranasal routes is a clinically important question to be investigated.

There were limitations to this study. Higher doses of modafinil could have been tested, although the current doses were chosen based on the observation that 3 times the single therapeutic dose is often tested in order to assess abuse liability (Balster and Bigelow, 2003). These are also the doses that are being considered for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Requesting that participants remain at the laboratory for the entire day would have led to more post-dose ratings, which may have resulted in a more sensitive time course. Lastly, a question asking participants specifically why particular choices were made would have been a reasonable addition to the design. Nevertheless, these data indicate that modafinil is unlikely to be abused in the population for which it may be an effective treatment, and support the notion that further consideration of modafinil as a pharmacotherapy for cocaine abuse and dependence is warranted.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abreu ME, Bigelow GE, Fleisher L, Walsh SL. Effect of intravenous injection speed on responses to cocaine and hydromorphone in humans. Psychopharmacology. 2001;154:76–84. doi: 10.1007/s002130000624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balster RL, Bigelow GE. Guidelines and methodological reviews concerning drug abuse liability assessment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70:S13–S40. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balster RL, Schuster CR. Fixed-interval schedule of cocaine reinforcement: Effect of dose and infusion duration. J Exp Anal Behav. 1973;20:119–129. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1973.20-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Swanson JM, Wigal SB, Boellner SW, Earl CQ, Lopex FA Modafinil ADHD Study Group. A comparison of once-daily and divided doses of modafinil in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:727–735. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackhall L, Petroni G, Shu J, Baum L, Farace E. A pilot study evaluating the safety and efficacy of modafinil for cancer-related fatigue. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:433–439. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Sullivan MA, Whittington RA, Vosburg SK, Kowalczyk WJ. Abuse liability of prescription opioids compared to heroin in morphine-maintained heroin abusers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1179–1191. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis C, O’Brien C. Glutamatergic agents for cocaine dependence. Annals N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:328–345. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis CA, Lynch KG, Yu E, Samaha FF, Kampman KM, Cornish JW, Rowan A, Poole S, White L, O’Brien CP. Modafinil and cocaine: A double-blind, placebo-controlled drug interaction study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70:29–37. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00335-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis CA, Kampman KM, Lynch KG, Pettinati HM, O’Brien CP. A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of modafinil for cocaine dependence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:205–211. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deroche-Gamonet V, Darnaudéry M, Bruins-Slot L, Piat F, Le Moal M, Piazza PV. Study of the addictive potential of modafinil in naive and cocaine-experienced rats. Psychopharmacology. 2002;161:387–395. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Self-administration of cocaine by humans: Choice between smoked and intravenous cocaine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;261:841–849. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin RW, Ward AS, Haney MH, Hart CL, Collins ED. The effects of escalating doses of smoked cocaine in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;70:149–157. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold LH, Balster RL. Evaluation of the cocaine-like discriminative stimulus effects and reinforcing effects of modafinil. Psychopharmacology. 1996;126:286–292. doi: 10.1007/BF02247379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Haney M, Vosburg SK, Rubin E, Foltin RW. Smoked cocaine self-administration is decreased by modafinil. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:761–768. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski DR. An evaluation of the abuse potential of modafinil using methylphenidate as a reference. J Psychopharmacol. 2000;14:53–60. doi: 10.1177/026988110001400107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasinski DR, Kovačević-Ristanović R. Evaluation of the abuse liability of modafinil and other drugs for excessive daytime sleepiness associated with narcolepsy. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2000;23:149–156. doi: 10.1097/00002826-200005000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karila L, Gorelick D, Weinstein A, Noble F, Benyamina A, Coscas S, Blecha L, Lowenstein W, Martinot JL, Reynaud M, Lépine JP. New treatments for cocaine dependence: A focused review. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:425–438. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707008097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam JY, Freeman MK, Cates ME. Modafinil augmentation for residual symptoms of fatigue in patients with a partial response to antidepressants. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:1005–1012. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange R, Volkmer M, Heesen C, Liepert J. Modafinil effects in multiple sclerosis patients with fatigue. J Neurol. 2009;256:645–650. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madras BK, Xie Z, Lin Z, Jassen A, Panas H, Lynch L, Johnson R, Livni E, Spencer TJ, Bonab AA, Miller GM, Fischman AJ. Modafinil occupies dopamine and norepinephrine transporteds in vivo and modulates the transporters and trace amine activity in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:561–569. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.106583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm R, Book SW, Moak D, DeVane L, Czepowicz V. Clinical applications of modafinil in stimulant abusers: low abuse potential. Am J Addict. 2002;11:247–249. doi: 10.1080/10550490290088027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcolm R, Swayngim K, Donovon JK, DeVane CL, Elkashefl A, Chiang N, Khan R, Mojsiak J, Myrick DL, Hedden S, Cochran K, Woolson RF. Modafinil and cocaine interactions. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:577–587. doi: 10.1080/00952990600920425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrick H, Malcolm R, Taylor B, LaRowe S. Modafinil: preclinical, clinical, and post-marketing surveillance - a review of abuse liability issues. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004;16:101–109. doi: 10.1080/10401230490453743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pataki CS, Feinberg DT, McGough JJ. New drugs for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 9:293–302. doi: 10.1517/14728214.9.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CR, Kelly TH, Hays LR, Baker RW, Wooten AF. Acute behavioral and physiological effects of modafinil in drug abusers. Behav Pharmacol. 2002a;13:105–115. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200203000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CR, Kelly TH, Hays LR, Wooten AF. Discriminative-stimulus effects of modafinil in cocaine-trained humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2002b;67:311–322. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(02)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaha AN, Mallet N, Ferguson SM, Gonon F, Robinson TE. The rate of cocaine administration alters gene regulation and behavioral plasticity: Implications for addiction. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6362–6370. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1205-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Logan J, Alexoff D, Zhu W, Telang F, Wang GJ, Jayne M, Hooker JM, Wong C, Hubbard B, Carter P, Warner D, King P, Shea C, Xu Y, Miench L. Effects of modafinil on dopamine and dopamine transporters in the male human brain: Clinical implications. JAMA. 2009a;301:1148–1154. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Baler R, Telang F. Imaging dopamine’s role in drug abuse and addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009b;56:3–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolkowska D, Jain R, Rothman RB, Partilla JS, Roth BL, Setola V, Prisinzano TE, Baumann MH. Evidence for the involvement of dopamine transporters in behavioral stimulant effects of modafinil. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;329:738–746. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.146142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]