Abstract

CD8hiCD57+ T cells have previously been described as effector memory T cells with minimal expansion capacity and high susceptibility to activation-induced cell death. In contrast, we demonstrate here that CD8hiCD57+ T cells are capable of rapid expansion using multiple techniques including [3H]thymidine uptake, flow cytometric bead-based enumeration and standard haemocytometer counting. Previous reports can be explained by marked inhibition of activation-induced expansion and increased 7-amino-actinomycin D uptake by CD8hiCD57+ T cells following treatment with CFSE, a dye previously used to measure their proliferation, combined with specific media requirements for the growth of this cell subset. The ability of CD8hiCD57+ T cells to further differentiate is highlighted by a distinct cytokine profile late after activation that includes the unexpected release of high levels of interleukin 5. These data indicate that CD8hiCD57+ T cells should not be considered as “end-stage” effector T cells incapable of proliferation, but represent a highly differentiated subset capable of rapid division and exhibiting novel functions separate from their previously described cytotoxic and IFN-γ responses.

Keywords: CD57, CD8+ T cells, IL-5

Introduction

CD8 and CD57 positivity identifies a subset of T cells, increased numbers of which are associated with a wide range of chronic diseases (summarised in [1]) including a proportion of phenotypically distinct large granular lymphocyte leukaemias [2]. Furthermore, infection by HIV [3], human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) [4-6] and Mycobacterium tuberculosis [7] drive stable expansions of these cells. Studies have shown that, in healthy HCMV-seropositive individuals, CD8+CD57+ T cells are oligoclonally derived [6], cytotoxic and produce IFN-γ and TNF-α in response to HCMV peptides [8, 9], and can represent up to 50% of the CD8+ T cell repertoire in aged subjects [10]. Studies of CD8+ T cell differentiation have labelled CD8+CD57+ T cells as effector memory T cells capable of immediate functional activity [11].

Recent reports have indicated that CD8+CD57+ cells express shortened telomeres [12], are replicatively senescent and suffer from activation-induced cell death [13, 14]. These data have implied that CD8+CD57+ Tcells are “end-stage” differentiated and are primarily cytotoxic. However, this has also created a paradox whereby a T cell population that reportedly cannot divide and dies following activation, forms the largest stable, antigen-specific in vivo expansions known to man, with the potential to develop into lymphocytic leukaemias. We have investigated this contradiction and uncovered an explanation for this paradox as well as a novel function for this memory T cell subset.

Results and discussion

Proliferation of CD8hiCD57+ T cells

To investigate the contradiction that CD8hiCD57+ T cells have been reported to be incapable of division and die following activation [13] yet are stably and oligoclonally expanded [1], we compared proliferation of CD8hiCD57+ cells using four separate readouts, including [3H]thymidine incorporation, flow cytometric bead-based enumeration, standard haemocytometer counting and flow cytometric CFSE assays. In contrast to previous reports [13], [3H]thymidine assays showed significantly higher proliferation by CD8hiCD57+ cells compared to their CD8hiCD57− counterparts. This response peaked at 8 days after stimulation (Fig. 1A) and was dependent on IL-2 (Fig. 1B) and OKT3, resulting in more than sevenfold higher mean stimulation indices (n = four subjects) at the highest concentration of OKT3 (Fig. 1C).

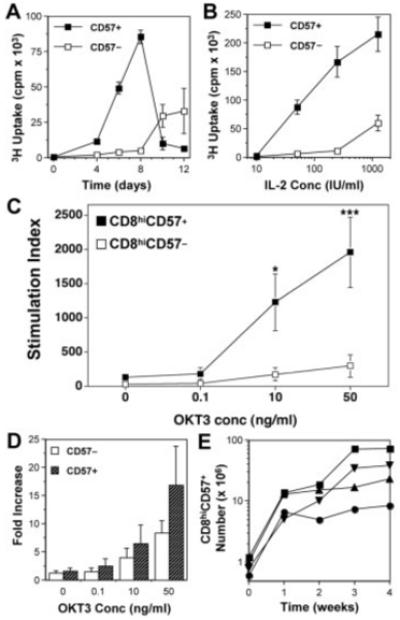

Figure 1.

Proliferation by CD8hiCD57+ cells. CD8hiCD57− and CD8hiCD57+ cells were purified by cell sorting (>95% purity) and stimulated for the indicated days with the indicated concentrations of either OKT3 and/or IL-2. (A) Time course of [3H]thymidine incorporation by CD8hiCD57+ (filled squares), compared to CD8hiCD57− cells (open squares). IL-2 concentration was 50 IU/mL. (B) Effect of various concentrations of IL-2 on the proliferation by CD8hiCD57+ (filled squares), compared to CD8hiCD57− cells (open squares) after 8 days of culture. Results are mean ± SEM from quadruplicate cultures. (C) Responses to OKT3 in the presence of 500 IU/mL IL-2 after 5 days of culture. Results are mean stimulation indices ± SEM from four separate subjects; *p=0.04, ***p=0.01 using t-test assuming unequal variance. (D) Expansion of CD8hiCD57+ cells (grey bars) compared to CD8hiCD57− cells (open bars) using bead-based enumeration. Results are mean fold increase + SEM from four separate subjects after 5 days of culture. (E) Time course showing live CD8hiCD57+ cell numbers over 4 wk from four separate subjects following stimulation with autologous HCMV-infected fibroblasts.

Because the time course indicated significant differences late (>4 days) after stimulation (Fig. 1A), further experiments were carried out following 5–8 days of culture. Using bead enumeration techniques to quantify cell number, we also recorded the expansion in numbers of live CD8hiCD57+ cells, either in short-term 5-day OKT3-stimulated cultures (Fig. 1D) or longer-term 4-wk cultures stimulated with HCMV-infected fibroblasts that equated to 13- to 60-fold expansions (Fig. 1E). In all of these cultures, CD8hiCD57+ cells maintained their phenotype (Supporting Information Fig. 1).

CFSE increases 7-amino-actinomycin D (7AAD) uptake and inhibits expansion of CD8hiCD57+ T cells

In our hands and in contrast to Brenchley and colleagues [13], CFSE assays also showed that CD8hiCD57+ cells were capable of division as measured by reduction in CFSE signal (Fig. 2A). However, CD8hiCD57+ cultures showed very high levels of 7AAD uptake (Fig. 2B), normally considered as a measure of cell death. These data suggested intrinsic problems with the combination of 7AAD and CFSE to determine cell death and proliferation, as the combined levels of apoptotic (7AADint) and dead (7AADhi) CD8hiCD57+ cells recorded in the presence of CFSE were too high (range 75–95%) to allow the expansion of cultures (Fig. 2C).

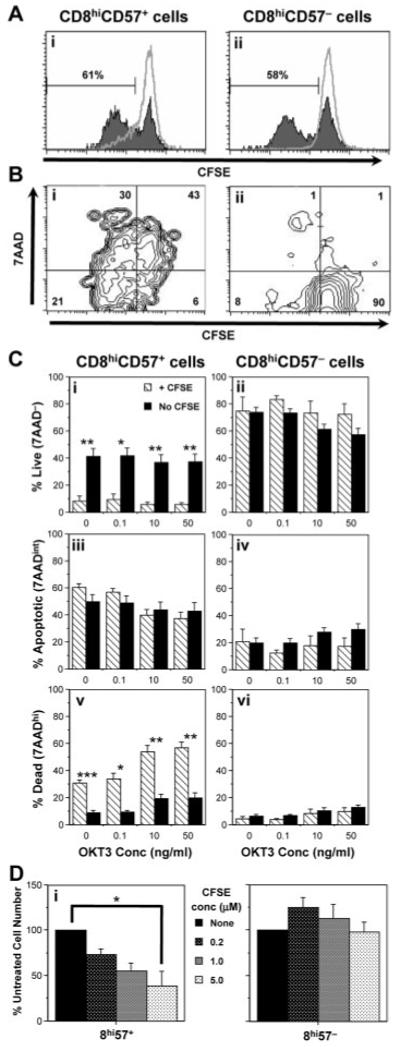

Figure 2.

Effect of CFSE on the proliferation and death of CD8hiCD57− and CD8hiCD57+ cells. (A) Cells were pre-labelled with CFSE and stimulated with 50 ng/mL OKT3. Proliferation was determined by reduction in CFSE signal after 8 days of culture. Proliferation of CD8hiCD57+ (Ai) and CD8hiCD57− (Aii) cells was recorded. Unstimulated peaks are shown as a grey line. (B) Proliferation in the presence of CFSE was accompanied by high levels of 7AAD uptake in CD8hiCD57+ (Bi), but not CD8hiCD57− cells (Bii). Representative plots from one of five experiments on five different subjects. Numbers represent the percentage in each quadrant, where live (no 7AAD uptake), undivided cells are found in the bottom right quadrant. (C) Labelling of sorted cells with CFSE (hatched bars) resulted in a fourfold decrease in 7AAD− (Ci) and threefold increase in 7AADhi (Cv) CD8hiCD57+ cells compared to data acquired in the absence of CFSE (filled bars). No significant effect was seen in CD8hiCD57− cells (Cii, Civ, Cvi). Results are mean % cells that were live (7AAD−), apoptotic (7AADint) or dead (7AADhi) + SEM from four (+ CFSE) or eight (no CFSE) separate subjects; *p<0.03, **p<0.001, ***p<0.00001 using t-test assuming unequal variance. (D) Increasing doses of CFSE inhibited the expansion of CD8hiCD57+ (Di), but not CD8hiCD57− cultures (Dii) stimulated with OKT3 and IL-2 for 7 days. Data are mean + SEM of three separate experiments. One-way ANOVA showed significance at *p<0.002.

To test this, we carried out assays in the presence or absence of CFSE. 7AAD uptake by CD8hiCD57+, but not CD8hiCD57− cells, was severely reduced in the absence of CFSE. Representative analysis from a single subject is detailed in Supporting Information Fig. 2. Overall, combined data from multiple (four to eight) subjects showed, in the absence of CFSE, a fourfold increase in the proportion of live 7AAD− (9 ± 3% vs. 42 ± 6%, p=0.004) and a threefold reduction in dead 7AADhi CD8hiCD57+ cells (31 ± 2% vs. 9 ± 2%, p=0.000008) (Fig. 2C; ranges shown in Supporting Information Fig. 3). A CFSE dose-dependent inhibition of numbers in OKT3- and IL-2-stimulated CD8hiCD57+, but not CD8hiCD57− cultures, was also observed (Fig. 2D). CFSE toxicity was primarily due to non-apoptotic mechanisms, as TUNEL staining of DNA strand breaks showed no significant changes in apoptotic CD8hiCD57+ cell number after CFSE treatment (Supporting Information Fig. 4).

Production of IL-5 by CD8hiCD57+ T cells

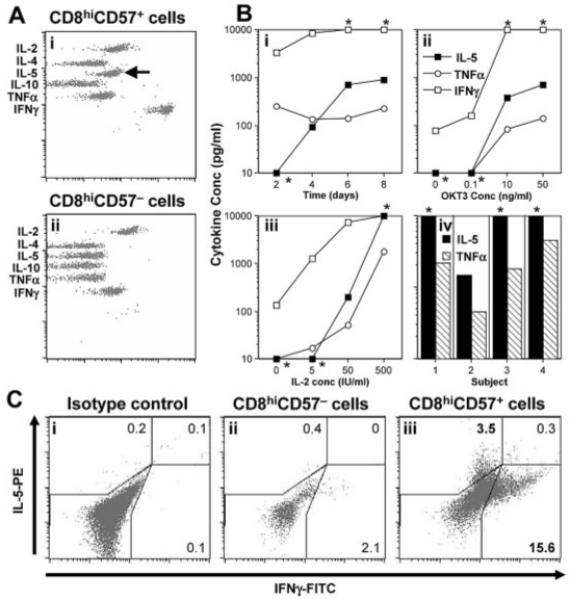

The ability of CD8hiCD57+ cells to proliferate to anti-CD3 stimulation suggested that this subset was not necessarily “end-stage” effector memory, but capable of further division and activity. We tested this hypothesis by investigating their cytokine release using a Th1/Th2 cytometric bead array. Exogenously added IL-2 was detected in all cultures and acted as a positive control. As previously reported [8], CD8hiCD57+, but not CD8hiCD57− cultures produced high levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α. Surprisingly, at later time points (>4 days), CD8hiCD57+ cultures also contained significant amounts of IL-5 (Fig. 3A). IL-5 levels proceeded to increase with time and were dependent on both the strength of the anti-CD3 signal and the amount of exogenous IL-2 added (Fig. 3B). By day 6, levels of IL-5 were second only to levels of IFN-γ in CD8hiCD57+ cultures. This was reproduced from four unrelated subjects (Fig. 3Biv). Intracellular cytokine staining and gating of cultures for CD8/CD57 subsets demonstrated that CD8hiCD57+ cells were the source of IL-5 and this population was distinct from the one that produced IFN-γ (Fig. 3C; Supporting Information Fig. 5).

Figure 3.

Cytokine production by CD8hiCD57− and CD8hiCD57+ cells. Following cell sorting, CD8hiCD57− and CD8hiCD57+ cells (>95% purity) were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of OKT3 and IL-2. (A) Representative flow cytometry plot of a cytometric bead array indicating the presence of IL-5 (arrow), TNF-α and higher levels of IFN-γ in CD8hiCD57+ cultures (Ai), but not CD8hiCD57− cultures (Aii), after 4 days. (B) Representative data showing IFN-γ (open squares), IL-5 (filled squares) and TNF-α concentrations (open circles) during a time course (Bi), dose responses to OKT3 (Bii) and IL-2 in the presence of 50 ng/mL OKT3 (Biii) at day 8. Results of IL-5 (filled bars) and TNF-α (hatched bars) from four separate subjects (Biv) at day 8; *values that fell outside the quantitation range of the cytometric bead array. (C) Representative flow cytometric plots of intracellular cytokine staining for IL-5 and IFN-γ, 4 days after stimulation. Only CD8hiCD57+ cells (Ciii) produced IL-5. The IL-5-producing cells were distinct from those producing IFN-γ (Ciii).

Current literature suggests that CD8+ T cell subsets defined by the expression of CD57 are effector memory T cells that have shortened telomeres and are therefore incapable of proliferation and highly susceptible to activation-induced cell death [13]. Here, we show that CD8hiCD57+ cells from healthy subjects are capable of rapid expansion of numbers, though they are generally (i.e. even without activation) more susceptible to cell death than their CD8hiCD57− counterparts.

The previously reported [13, 15] lack of proliferation by CD8hiCD57+ cells can be explained by a number of differences between our own studies and those of others. Brenchley et al. [13] activated their T cells either with peptides or bacterial super-antigens added to PBMC with low exogenous cytokines and derived some samples from HIV patients. Le Priol et al. [15] recorded reduced proliferation following stimulation with anti-CD3 and a range of different cytokines in both HIV patients and healthy controls. We used plate-bound OKT3 to stimulate, but added higher levels of exogenous IL-2 and studied only healthy subjects. Thus, a requirement for high levels of cytokines or specific differentiation pathways associated with HIV infection could explain some of the differences. However, we also studied proliferation over a longer period (5–8 days vs. 48 h) and most significantly, used human AB serum rather than FCS in our assays. We have found that proliferation of CD8hiCD57+ T cells is severely impaired in FCS (Supporting Information Fig. 6).

Our findings also demonstrate inhibition of expansion and high susceptibility of CD8hiCD57+ cells to 7AAD uptake in the presence of CFSE (Fig. 2C). Toxicity of CFSE to adipocytes [16] and dendritic cells [17] is documented, but lymphocytes normally tolerate CFSE well [18]. In this context, it is of note that, in our study, CD8hiCD57− cells did not suffer any significant toxicity at the same CFSE concentrations (Fig. 2). CFSE non-specifically binds cytoplasmic proteins [19] and may therefore interfere with intracellular pathways essential for the survival of CD8hiCD57+ cells. The underlying mechanisms of this specific toxicity remain an area of further research, but it is clear that CFSE should not be used to determine proliferation of this particular cell subset.

Further study of the function of CD8hiCD57+ cells is warranted as we also show that these cells produce IL-5, a cytokine that drives the differentiation of eosinophils in humans [20] and aids class switching of the antibody response in mice [21]. CD8+ T cells that produce IL-4 and IL-5 have been described previously. These Tc2 cells are capable of both cytotoxicity and provision of bystander help (reviewed in [22]). This is the first description of CD8hiCD57+ cells from healthy subjects being capable of producing IL-5 as previous reports have indicated a cytotoxic role with an IFN-γ and TNF-α cytokine profile [8, 9]. Interestingly, CD8hiCD57+ T cells are found at high numbers in the bronchoalveolar lavage of HIV patients [23] and have been shown to be suppressive of cytotoxic function [24]. An increase in CD8+ T cell clones with Tc0/Tc2 cytokine profile has been recorded following HIV infection, though these were not specifically phenotyped for CD57 expression [25]. IL-5 production may therefore represent a previously overlooked intrinsic function of this T cell subset associated with control of immune responses in the lung.

Concluding remarks

To summarise, our data clearly indicate that CD8hiCD57+ T cells are highly proliferative and have a unique cytokine profile. They should not be considered an “end-stage” IFN-γ- and TNF-α-producing T cell subset that dies following activation, but one capable of rapid division and multiple diverse functions. These data make CD57 a misleading marker for replicative senescent T cells as has been suggested in the literature.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

Prior consent was obtained from donors, who were all healthy and aged between 22 and 50 years. The study was approved by the local research ethics committee (Bro Taf LREC, Cardiff, UK).

Antibodies, flow cytometry and cell sorting

Monoclonal antibodies (mAb) [anti-CD8-allophycocyanin, anti-CD8-biotin, anti-IL-5-PE, anti-IFN-γ-FITC, anti-CD57 (HNK-1), anti-CD57-FITC] and secondary reagents (streptavidin-allophycocyanin and anti-mIgM-PerCP-Cy5.5) were acquired from Caltag Laboratories or BD Biosciences. Four-colour flow cytometry was carried out on FACSCalibur flow cytometers and analysed with CellQuest Pro software (BD Biosciences). Cell sorting using a MoFlo (Cytomation) was provided by the Central Biotechnology Service, Cardiff University. The hybridoma of the anti-CD3 mAb, OKT3, was acquired from the American Type Culture Collection. Intracellular cytokine staining was performed as described by BD Biosciences.

Proliferation and cell death assays

PBMC were isolated using standard density centrifugation techniques [6] and CD8hiCD57− or CD8hiCD57+ cells of >95% purity were obtained through cell sorting. For fluorescence-based proliferation assays, cells were treated with CFSE (1 μM) as described [26] before washing and re-suspension in DMEM (Invitrogen, Netherlands) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated AB serum (Welsh Blood Transfusion Service, UK) and 500 IU/mL recombinant IL-2 (Proleukin; Cetus) (DMEM-10) prior to culture on OKT3-coated tissue culture plates. Cultures were stained with mAb, followed by addition of 7AAD (BD Biosciences).

Live, apoptotic or dead cells were defined using forward scatter vs. 7AAD plots as described [27] or apoptotic cells using TUNEL staining of DNA strand breaks with the MEBSTAIN apoptosis kit (Beckman Coulter). For quantitative enumeration of cell numbers, Flow-Count™ Fluorospheres (Beckman Coulter) were used as per the manufacturer’s instructions. [3H]thymidine incorporation assays were performed as previously described [6]. For long-term expansion, CD57+ and CD57− cells were purified using HNK-1- and anti-IgM-coated Dynabeads (Dynal, UK) and stimulated with irradiated, autologous HCMV-infected fibroblasts [6]. Each week, cultures were stained for CD8 and CD57 and viable cell numbers calculated by cell counting.

Quantitative cytokine analysis

Supernatants (50 μL) were collected and stored at −20°C until analysis. Cytokine concentrations were determined using cytometric bead arrays (BD Biosciences) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Chris Pepper for performing cell sorting and the Central Biotechnology Service, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, for providing access to flow cytometers. This work was supported by grants awarded to E.W. from The Wellcome Trust (GR066749) and the Medical Research Council (G0500617). E.W. also holds an MRC Career Establishment Grant (G0300180).

Abbreviations

- 7AAD

7-amino-actinomycin D

- HCMV

human cytomegalovirus

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wang EC, Borysiewicz LK. The role of CD8+, CD57+ cells in human cytomegalovirus and other viral infections. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. Suppl. 1995;99:69–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan WC, Link S, Mawle A, Check I, Brynes RK, Winton EF. Heterogeneity of large granular lymphocyte proliferations: Delineation of two major subtypes. Blood. 1986;68:1142–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis DE, Puck JM, Babcock GF, Rich RR. Disproportionate expansion of a minor T cell subset in patients with lymphadenopathy syndrome and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J. Infect. Dis. 1985;151:555–559. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gratama JW, Langelaar RA, Oosterveer MA, van der Linden JA, den Ouden-Noordermeer A, Naipal AM, Visser JW, et al. Phenotypic study of CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocyte subsets in relation to cytomegalovirus carrier status and its correlate with pokeweed mitogen-induced B lymphocyte differentiation. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1989;77:245–251. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang EC, Taylor-Wiedeman J, Perera P, Fisher J, Borysiewicz LK. Subsets of CD8+, CD57+ cells in normal, healthy individuals: Correlations with human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) carrier status, phenotypic and functional analyses. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1993;94:297–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb03447.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang EC, Moss PA, Frodsham P, Lehner PJ, Bell JI, Borysiewicz LK. CD8highCD57+ T lymphocytes in normal, healthy individuals are oligoclonal and respond to human cytomegalovirus. J. Immunol. 1995;155:5046–5056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sada-Ovalle I, Torre-Bouscoulet L, Valdez-Vazquez R, Martinez-Cairo S, Zenteno E, Lascurain R. Characterization of a cytotoxic CD57+ T cell subset from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin. Immunol. 2006;121:314–323. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kern F, Khatamzas E, Surel I, Frommel C, Reinke P, Waldrop SL, Picker LJ, Volk HD. Distribution of human CMV-specific memory T cells among the CD8pos. subsets defined by CD57, CD27, and CD45 isoforms. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29:2908–2915. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199909)29:09<2908::AID-IMMU2908>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weekes MP, Wills MR, Mynard K, Hicks R, Sissons JG, Carmichael AJ. Large clonal expansions of human virus-specific memory cytotoxic T lymphocytes within the CD57+ CD28− CD8+ T-cell population. Immunology. 1999;98:443–449. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00901.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan N, Shariff N, Cobbold M, Bruton R, Ainsworth JA, Sinclair AJ, Nayak L, Moss PA. Cytomegalovirus seropositivity drives the CD8 T cell repertoire toward greater clonality in healthy elderly individuals. J. Immunol. 2002;169:1984–1992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.4.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appay V, Dunbar PR, Callan M, Klenerman P, Gillespie GM, Papagno L, Ogg GS, et al. Memory CD8+ T cells vary in differentiation phenotype in different persistent virus infections. Nat. Med. 2002;8:379–385. doi: 10.1038/nm0402-379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Monteiro J, Batliwalla F, Ostrer H, Gregersen PK. Shortened telomeres in clonally expanded CD28−CD8+ T cells imply a replicative history that is distinct from their CD28+CD8+ counterparts. J. Immunol. 1996;156:3587–3590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brenchley JM, Karandikar NJ, Betts MR, Ambrozak DR, Hill BJ, Crotty LE, Casazza JP, et al. Expression of CD57 defines replicative senescence and antigen-induced apoptotic death of CD8+ T cells. Blood. 2003;101:2711–2720. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shinomiya N, Koike Y, Koyama H, Takayama E, Habu Y, Fukasawa M, Tanuma S, Seki S. Analysis of the susceptibility of CD57 T cells to CD3-mediated apoptosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2005;139:268–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02687.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Le Priol Y, Puthier D, Lecureuil C, Combadiere C, Debre P, Nguyen C, Combadiere B. High cytotoxic and specific migratory potencies of senescent CD8+ CD57+ cells in HIV-infected and uninfected individuals. J. Immunol. 2006;177:5145–5154. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hemmrich K, Meersch M, von Heimburg D, Pallua N. Applicability of the dyes CFSE, CM-DiI and PKH26 for tracking of human preadipocytes to evaluate adipose tissue engineering. Cells Tissues Organs. 2006;184:117–127. doi: 10.1159/000099618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leon B, Martinez del Hoyo G, Parrillas V, Vargas HH, Sanchez-Mateos P, Longo N, Lopez-Bravo M, Ardavin C. Dendritic cell differentiation potential of mouse monocytes: Monocytes represent immediate precursors of CD8− and CD8+ splenic dendritic cells. Blood. 2004;103:2668–2676. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weston SA, Parish CR. New fluorescent dyes for lymphocyte migration studies. Analysis by flow cytometry and fluorescence microscopy. J. Immunol. Methods. 1990;133:87–97. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90322-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Banks PR, Paquette DM. Comparison of three common amine reactive fluorescent probes used for conjugation to biomolecules by capillary zone electrophoresis. Bioconjug. Chem. 1995;6:447–458. doi: 10.1021/bc00034a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karlen S, De Boer ML, Lipscombe RJ, Lutz W, Mordvinov VA, Sanderson CJ. Biological and molecular characteristics of interleukin-5 and its receptor. Int. Rev. Immunol. 1998;16:227–247. doi: 10.3109/08830189809042996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takatsu K. Interleukin 5 and B cell differentiation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1998;9:25–35. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(97)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosmann TR, Li L, Sad S. Functions of CD8 T-cell subsets secreting different cytokine patterns. Semin. Immunol. 1997;9:87–92. doi: 10.1006/smim.1997.0065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sadat-Sowti B, Parrot A, Quint L, Mayaud C, Debre P, Autran B. Alveolar CD8+CD57+ lymphocytes in human immunodeficiency virus infection produce an inhibitor of cytotoxic functions. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994;149:972–980. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.4.7511468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadat-Sowti B, Debre P, Mollet L, Quint L, Hadida F, Leblond V, Bismuth G, Autran B. An inhibitor of cytotoxic functions produced by CD8+CD57+ T lymphocytes from patients suffering from AIDS and immunosuppressed bone marrow recipients. Eur. J. Immunol. 1994;24:2882–2888. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maggi E, Manetti R, Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Giudizi MG, Biagiotti R, Galli G, et al. Functional characterization and modulation of cytokine production by CD8+ T cells from human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals. Blood. 1997;89:3672–3681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sathish JG, Dolton G, Leroy FG, Matthews RJ. Loss of Src homology region 2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-1 increases CD8+ T cell-APC conjugate formation and is associated with enhanced in vivo CTL function. J. Immunol. 2007;178:330–337. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams O. Flow cytometry-based methods for apoptosis detection in lymphoid cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2004;282:31–42. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-812-9:031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.