Abstract

Background

Comanagement of surgical patients by medicine physicians has been shown to improve efficiency and reduce adverse outcomes. We examined the extent to which comanagement is employed during hospitalizations for common surgical procedures in the United States.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries hospitalized for one of 15 inpatient surgical procedures in 1996 through 2006 (n=694,806). Proportion of Medicare beneficiaries comanaged by medicine physicians (generalist physicians or internal medicine subspecialists) during hospitalization.

Results

Between 1996 and 2006, 35.2% of patients hospitalized for a common surgical procedure were comanaged by a medicine physician: 23.7% by a generalist physician and 14% by an internal medicine subspecialist (2.5% were comanaged by both). The percentage of patients experiencing comanagement was relatively unchanged from 1996–2000, then increased sharply. The increase was entirely due to an increase in comanagement by generalist physicians. In a multivariable multilevel analysis, comanagement by generalist physicians increased 11.5% per year during 2001 to 2006. Patients with advanced age, more comorbidities, or receiving care in non-teaching, mid-size (200–499 beds) or for profit hospitals were more likely to receive comanagement. All of the growth in comanagement was attributed to increased comanagement by hospitalist physicians.

Conclusions

Medical comanagement of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for a surgical procedure is increasing because of the increasing role of hospitalists. To meet this growing need for comanagement, training in internal medicine should include medical management of surgical patients.

Introduction

Comanagement of surgical patients refers to patient care in which the medicine physician daily assesses acute issues, addresses medical comorbidities, communicates with surgeons, and facilitates patient care transition from the acute care hospital setting1.

Benefits of comanagement include: increased prescribing of evidence-based treatments2; reduced time to surgery3; fewer transfers to an ICU for acute medical deterioration4; lower post-operative complications4–6; increased likelihood of discharge to home4; reduced length of stay7; improved nurse and surgeon satisfaction5; and a lower 6-month readmission rate2.

Using a 5% national Medicare sample, we examined the rate of comanagement of surgical patients by generalist physicians or internal medicine subspecialists in US hospitals from 1996 through 2006. We also examined how comanagement by medicine physicians varied by type of surgery, and by patient and hospital characteristics.

Methods

The study cohort consisted of 694,806 hospital admissions in the 5% Medicare sample who had inpatient surgery between 1996 and 2006 and were discharged with a surgical Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) associated with at least one of the following procedures: cholecystectomy (DRG 493, 195, 196, 197, 198); resection for colorectal cancer (DRG 148, 149); abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (DRG 110); lower extremity revascularization (DRG 553, 554, 478); major leg amputation (DRG 113, 213, 285); coronary artery bypass grafting surgery (DRG 105, 547, 548, 549, 550); aortic/mitral valve replacement (DRG 104, 105); lung resection for cancer (DRG 75); radical prostatectomy (DRG 334); transurethral resection of the prostate for BPH (DRG 476, 306); radical nephrectomy for renal cancer (DRG 303); back surgery (DRG 496, 497, 498, 499); knee replacement (DRG 544); hip replacement (DRG 544); and repair of hip fracture (DRG 210, 211, 544). Surgical DRGs selected were those used by the Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare7 for benchmarking US hospitals and associated with a mean length of stay >3 days.

We identified two types of comanagement: that by a generalist physician (i.e., general internist, geriatrician, family practitioner or general practitioner) and that by an internal medicine subspecialist.

Comanagement was defined by the relevant physician (generalist or internal medicine subspecialist) submitting a claim for evaluation and management services on ≥70% of the days the patient was hospitalized, including partial days (i.e., admission and discharge days).

Inpatient physician claims were identified using AMA-CPT E&M codes 99221–99223 (initial hospital visit), 99251–99255 (inpatient consultation) and 99231–99233 (subsequent hospital visit). We also analyzed the effect of various cutpoints for minimum percent of total hospital days for which a medicine physician provided care.

In some analyses we examined comanagement of surgical patients by hospitalist physicians, as previously defined.8

Statistical Analyses

The proportion of admissions comanaged by any medicine physician was calculated, then stratified by patient and hospital characteristics. Linear trend in percentage of patients comanaged from 1996 to 2006 was tested using likelihood ratio test. Two trends were identified: during 1996–2000 and during 2001–2006. Hierarchical generalized linear models with a logistic link, adjusting for clustering of admissions (level 1) within hospitals (level 2), were constructed to evaluate comanagement during 2001–2006 with any medicine physician or generalist physician.

Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.1 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC). GLIMMIX was used to conduct multilevel analyses.

Results

Between 1996 and 2006, 35.2% of patients hospitalized for a common surgical procedure were comanaged by medicine physicians: 23.7% by a generalist physician and 14% by an internal medicine subspecialist (2.5% were comanaged by both).

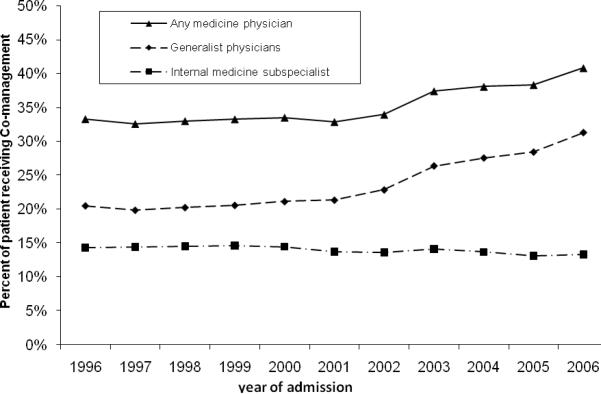

Comanagement by any medicine physician for patients hospitalized for a surgical procedure increased from 33.3% in 1996 to 40.8% in 2006 (p<0.001). A likelihood ratio test showed two distinct time trends (p<0.001). The percentage of surgical patients receiving comanagement changed little during the late 1990s, then increased in 2001(Figure1). The increase in comanagement was limited to comanagement by generalist physicians. Comanagement by generalist physicians increased from 20.5% in 1996 to 31.3% in 2006 (p<0.001). This increase was entirely due to an increase in comanagement by generalist physicians who were hospitalists. Comanagement by hospitalists increased from 1.7% of patients in 1996 to 12.5% in 2006.

Figure 1. Trends in comanagementa of patients hospitalized for a surgical procedure between 1996 and 2006 by a generalist physicianb, internal medicine sub-specialistc or any medicine physiciand.

aA patient is defined as “having comanagement” if any medicine physician submitted evaluation and management (E&M) claims for at least 70% of the days during the patients hospital stay for a surgical procedure.

bAny medicine physician: either a generalist physician or an internal medicine subspecialist

cGeneralist physician includes: internal medicine physician, geriatrician, family practitioner or a general practitioner

dInternal medicine subspecialist includes: pulmonary, cardiology, gastroenterology, endocrinology, rheumatology, nephrology, infectious disease and hematology/oncology.

For all point estimates the 95% confidence interval are less than 0.5% and are not shown.

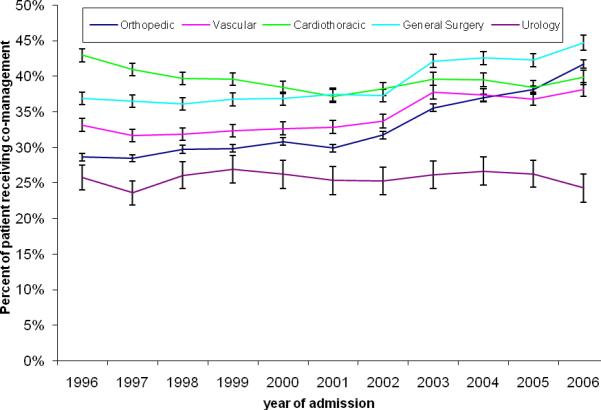

The percent of patients comanaged by a medicine physician varied by type of surgery (Figure 2). For example, comanagement by a medicine physician increased from 28.6% in 1996 to 41.7% in 2006 (p<0.001) for patients hospitalized for orthopedic surgery but actually decreased for patients hospitalized for cardiothoracic surgery, from 43.0% in 1996 to 39.9% in 2006 (p<0.001).

Figure 2. Trends in medical comanagement by type of surgery for patients hospitalized for a surgical procedure between 1996 and 2006.

General surgery includes cholecystectomy (DRG 493, 195, 196, 197, 198) and resection for colorectal cancer (DRG 148, 149),

Vascular surgery includes abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (DRG 110), lower extremity revascularization (DRG 553, 554, 478) and major leg amputation (DRG 113, 213, 285)

Cardiothoracic surgery includes coronary artery bypass grafting (DRG 105, 547, 548, 549, 550), aortic/mitral valve replacement (DRG 104, 105) and lung resection for cancer (DRG 75)

Urology includes radical prostatectomy (DRG 334), transurethral resection of the prostrate for BPH (476, 306) and radical nephrectomy for renal cancer (DRG 303)

Orthopedic surgery includes back surgery (DRG 496, 497, 498, 499), knee replacement (DRG 544), hip replacement (DRG 544) and repair for hip fracture (DRG 210, 211, 544)

Table 1 shows how comanagement varied by patient and hospital characteristics. Older adults, females, those with low socioeconomic status and those with more comorbidities were more likely to receive comanagement. Most comanaged patients were seen by a generalist physician, except for those undergoing cardiothoracic surgery, who were more likely to be comanaged by internal medicine subspecialists (almost entirely cardiologists or pulmonologists). Surgical patients cared for in non-teaching, mid-size and for-profit hospitals were more likely to receive medical comanagement.

Table 1.

Percent of surgical patients comanaged by any medicine physiciana or a generalist physicianb stratified by selected patient and hospital characteristicsc, 1996–2006 (n=694,806).

| Comanagement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | N | % with generalist physician | % with any medicine physician |

| All admissions | 694806 | 23.7% | 35.2% |

| Age | |||

| < 65 | 63232 | 16.5% | 27.2% |

| 65 – 74 | 255558 | 18.3% | 30.7% |

| 75 – 84 | 269365 | 24.9% | 37.0% |

| 85 + | 106651 | 37.5% | 46.2% |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 305573 | 20.1% | 34.0% |

| Female | 389233 | 26.4% | 36.1% |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 613990 | 23.7% | 35.3% |

| Black | 54090 | 23.4% | 33.7% |

| Others | 26726 | 22.5% | 35.4% |

| Low Socioeconomic status | |||

| No | 582807 | 23.0% | 34.8% |

| Yes | 111999 | 26.8% | 37.4% |

| Emergency admission | |||

| No | 497618 | 18.0% | 29.5% |

| Yes | 197188 | 37.9% | 49.7% |

| Type of surgery | |||

| Orthopedic | 321502 | 27.9% | 33.2% |

| Vascular | 113029 | 20.6% | 34.4% |

| Cardiothoracic | 118661 | 10.6% | 39.5% |

| General Surgery | 119392 | 29.3% | 38.9% |

| Urology | 22222 | 17.5% | 25.7% |

| Comorbidity Score | |||

| 0 | 147483 | 19.7% | 28.6% |

| 1 | 166208 | 21.6% | 31.8% |

| 2 | 131771 | 23.8% | 35.8% |

| >=3 | 249344 | 27.2% | 41.1% |

| Census Regions | |||

| Middle Atlantic | 93539 | 25.5% | 41.3% |

| New England | 35228 | 10.2% | 16.3% |

| East North Central | 126090 | 25.8% | 34.8% |

| West North Central | 61938 | 29.1% | 36.9% |

| South Atlantic | 145081 | 21.2% | 32.7% |

| East South Central | 54762 | 26.7% | 38.9% |

| West South Central | 75671 | 28.3% | 43.7% |

| Mountain | 35021 | 20.9% | 30.4% |

| Pacific | 62860 | 18.2% | 31.9% |

| Teaching affiliation | |||

| Non | 350442 | 26.6% | 37.4% |

| Minor | 170911 | 24.2% | 36.6% |

| Major | 173453 | 17.2% | 29.4% |

| Hospital size | |||

| < 200 beds | 154895 | 27.7% | 33.6% |

| 200 – 349 | 184456 | 26.0% | 37.4% |

| 350 – 499 | 147312 | 23.1% | 37.4% |

| >=500 | 208143 | 19.0% | 32.9% |

| Type of hospital | |||

| Non-profit | 539144 | 23.5% | 35.3% |

| For profit | 75076 | 27.1% | 40.2% |

| Public | 80586 | 21.6% | 29.7% |

| Received hospitalist care | |||

| No | 624259 | 20.5% | 32.5% |

| Yes | 70547 | 51.8% | 58.9% |

Any medicine physician: either a generalist physician or an internal medicine subspecialist

Generalist physician includes: general internal medicine physician, geriatrician, family practitioner or a general practitioner

All percents across either patient or hospital characteristics were statistically significantly different at p<0.001 level.

After adjusting for other variables, comanagement by a generalist physician increased at 11.4% per year and overall comanagement by any medicine physician increased 7.8% per year during 2001–2006 (Table 2). Advanced age, emergency admissions and increasing comorbidities were all strong predictors of comanagement. Patients cared for in major teaching hospitals were substantially less likely to receive comanagement. Comanagement varied widely by region, with patients in New England much less likely than others to be comanaged.

Table 2.

Multilevel analyses of odds of comanagement with a generalist physiciana and with any medicine physicianb for a patient hospitalized for a surgical procedure between 2001 and 2006.

| Variable | With generalist physicianc Odds Ratio (95% CI) | With any medicine physicianc Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Year of admission | 1.114 (1.109–1.119) | 1.078 (1.073–1.082) |

|

| ||

| Age | ||

| <65 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 65–74 | 1.281 (1.241–1.323) | 1.264 (1.228–1.300) |

| 75–84 | 1.621 (1.570–1.673) | 1.573 (1.529–1.618) |

| 85+ | 2.135 (2.063–2.211) | 2.033 (1.969–2.099) |

|

| ||

| Sex | ||

| Female | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Male | 0.946 (0.930–0.962) | 1.007 (0.992–1.023) |

|

| ||

| Race | ||

| White | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Black | 1.117 (1.081–1.153) | 0.955 (0.927–0.984) |

| Others | 0.990 (0.948–1.033) | 0.938 (0.902–0.976) |

|

| ||

| Low Socioeconomic status | 1.148 (1.121–1.174) | 1.098 (1.074–1.122) |

|

| ||

| Emergency admission | 2.714 (2.666–2.762) | 2.625 (2.581–2.670) |

|

| ||

| Type of surgery | ||

| General Surgery | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Orthopedic | 1.090 (1.067–1.113) | 0.890 (0.871–0.908) |

| Vascular | 0.680 (0.661–0.699) | 0.848 (0.826–0.871) |

| Cardiothoracic | 0.390 (0.377–0.403) | 1.341 (1.306–1.377) |

| Urology | 0.672 (0.637–0.710) | 0.682 (0.649–0.716) |

|

| ||

| Co-morbidity score | ||

| 0 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 1 | 1.131 (1.103–1.160) | 1.161 (1.135–1.189) |

| 2 | 1.288 (1.255–1.322) | 1.352 (1.320–1.385) |

| >=3 | 1.607 (1.569–1.645) | 1.753 (1.715–1.792) |

|

| ||

| Census Regions | ||

| New England | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Middle Atlantic | 2.539 (2.193–2.939) | 3.112 (2.687–3.605) |

| East North Central | 2.935 (2.551–3.376) | 2.854 (2.479–3.286) |

| West North Central | 3.332 (2.856–3.889) | 3.108 (2.660–3.630) |

| South Atlantic | 2.134 (1.851–2.459) | 2.386 (2.068–2.752) |

| East South Central | 2.842 (2.417–3.343) | 2.831 (2.404–3.332) |

| West South Central | 2.914 (2.511–3.381) | 3.266 (2.813–3.792) |

| Mountain | 1.926 (1.627–2.280) | 1.971 (1.664–2.335) |

| Pacific | 1.593 (1.373–1.849) | 2.084 (1.796–2.420) |

|

| ||

| Teaching Hospital | ||

| Non | 1.642 (1.484–1.818) | 1.725 (1.557–1.910) |

| Minor | 1.572 (1.411–1.751) | 1.627 (1.459–1.813) |

| Major | 1.000 | 1.000 |

|

| ||

| Hospital Size | ||

| <200 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| 200–349 | 1.126 (1.047–1.212) | 1.321 (1.227–1.422) |

| 350–499 | 0.994 (0.904–1.093) | 1.298 (1.180–1.428) |

| >=500 | 0.796 (0.713–0.887) | 1.027 (0.921–1.147) |

|

| ||

| Type of Hospital | ||

| Non-Profit | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| For Profit | 1.038 (0.954–1.129) | 1.176 (1.080–1.279) |

| Public | 0.820 (0.756–0.889) | 0.758 (0.699–0.823) |

Generalist physician includes: general internal medicine physician, geriatrician, family practitioner or general practitioner

Any medicine physician: includes a generalist physician or an internal medicine subspecialist

Adjusted for patient characteristics (including age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, emergency admission, type of surgery, and comorbidity) and hospital characteristics (including region, medical school affiliation, type of hospital, and hospital size).

In these analyses, we defined comanagement as participation of a medical physician on ≥70% of total hospital days. Using different cutpoints (e.g ≥50%, or ≥80% of hospital days) changed the estimates of percentage of patients receiving comanagement. However, the pattern of increase in comanagement over time, and the association of comanagement with patient and hospital characteristics did not change appreciably by cutpoint.

Conclusion

We found a rapid rise in the percentage of hospitalized surgical patients comanaged by a medicine physician. The increase, begun in 2001, was caused by more comanagement by generalist hospitalist physicians. The percentage of patients comanaged by internal medicine subspecialists or non-hospitalist generalist physicians was essentially unchanged from 1996 through 2006.

Orthopedic surgery patients experienced the fastest growth in medical comanagement, and the greatest overall use of comanagement by generalist physicians. Almost all studies of comanagement are in orthopedic patients2–6, 9. Indeed, the rapid growth in medical comanagement coincided with the first randomized controlled trials published in 2001, showing benefits of comanagement in orthopedic patients9. Clearly, prospective trials of medical comanagement are needed in other surgical disciplines.

The growth in care of surgical patients by medical physicians raises the issue of appropriate training. A cross sectional survey of generalist physicians who devoted ≥25% time to inpatient care revealed perioperative management was underemphasized during their training10. The American Council of Graduate Medical Education currently does not list competencies in perioperative management as a core requirement for internal medicine training11

The growth in comanagement by medicine physicians in our study was attributed to increased care by hospitalist physicians. Hospitalists are well suited to respond quickly to changes in postoperative patients. A recent survey found that 91% of hospitalists have cared for surgical patients12. The Society of Hospital Medicine recognizes perioperative management as a key skill for hospitalists and lists competencies in perioperative medicine as core requirements13

Older adults and those with comorbidities are more likely to receive comanagement. These patients are at higher risk for complications of surgery, and will more likely benefit from comanagement. In a recent study of Medicare beneficiaries, among patients re-hospitalized within 30 days of a surgical discharge, 70.5% were re-hospitalized for a medical condition14. Closer attention to medical comorbidities during initial hospitalization might be expected to reduce this rate.

The increase in comanagement of surgical patients by hospitalists has implications for number of hospitalists needed. If we assume that 100% of Medicare patients hospitalized for surgical procedures are to be followed by hospitalists that would require an additional of 2500 to 3000 full time equivalent hospitalists given the current workload of hospitalist15.

Our study has several limitations. First, we examined comanagement only in a fee-for-service Medicare population and findings may not be generalizable to non-Medicare patients. We studied fifteen common inpatient surgeries performed in this population, and results may not apply to other surgeries. These represent 39.1% of all surgical procedures in this population.

Our definition of comanagement — evaluation and management claims submitted on at least 70% of all hospital days by a medicine physician — is arbitrary. Using different cutpoints changed the proportion of patients comanaged but not the increasing trend. A further limitation is that we did not assess processes or outcomes of care and therefore cannot comment on any benefits of comanagement.

In summary, comanagement of surgical patients by medicine physicians is increasing. To meet this need, training in internal medicine should include medical management of surgical patients. Further prospective trials of comanagement in surgical patients in specialties other than orthopedic surgery are clearly needed.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants R01 AG 033134, K05 CA 134923, K08 AG 031583, and P30 AG 024832 from the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Sarah Toombs Smith, Ph.D., for help in preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the content of this manuscript.

Reference List

- (1).Whinney C, Michota F. Surgical comanagement: a natural evolution of hospitalist practice. J Hosp Med. 2008 September;3(5):394–7. doi: 10.1002/jhm.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Fisher AA, Davis MW, Rubenach SE, Sivakumaran S, Smith PN, Budge MM. Outcomes for older patients with hip fractures: the impact of orthopedic and geriatric medicine cocare. J Orthop Trauma. 2006 March;20(3):172–8. doi: 10.1097/01.bot.0000202220.88855.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Phy MP, Vanness DJ, Melton LJ, III, et al. Effects of a hospitalist model on elderly patients with hip fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2005 April 11;165(7):796–801. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.7.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zuckerman JD, Sakales SR, Fabian DR, Frankel VH. Hip fractures in geriatric patients. Results of an interdisciplinary hospital care program. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992 January;(274):213–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Huddleston JM, Long KH, Naessens JM, et al. Medical and surgical comanagement after elective hip and knee arthroplasty: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004 July 6;141(1):28–38. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-1-200407060-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Friedman SM, Mendelson DA, Bingham KW, Kates SL. Impact of a comanaged Geriatric Fracture Center on short-term hip fracture outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2009 October 12;169(18):1712–7. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).The Dartmouth Atlas of healthcare. [Accessed March 1, 2009];ICD-9 Procedure codes for Inpaient surgery. 2009 www dartmouthatlas org/faq/SxICD9codes pdf.

- (8).Kuo YF, Sharma G, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009 March 12;360(11):1102–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0802381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, Resnick NM. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 May;49(5):516–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Plauth WH, III, Pantilat SZ, Wachter RM, Fenton CL. Hospitalists' perceptions of their residency training needs: results of a national survey. Am J Med. 2001 August 15;111(3):247–54. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00837-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11). [Acccessed July10, 2009];ACGME Program requirement for Residents Education in Internal medicine. 2009 http://www acgme org/acWebsite/downloads/RRC_progReq/140_internal_medicine_07012009 pdf.

- (12).Vasilevskis E, Knebel J, Wachter R, Auerbach A. The rise of the hospitalists in California. California Healthcare Foundation; Oakland: 2007. Ref Type: Internet Communication. [Google Scholar]

- (13).The core competencies in hospital medicine: a framework for curriculum development by the society of hospital medicine. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(Suppl 1):2–95. doi: 10.1002/jhm.72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- (14).Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009 April 2;360(14):1418–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Society of Hospital Medicine-Biannaul Survey 2007-2008. 2009 http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Survey&Template=/CM/HTMLDisplay.cfm&ContentID=18412. Ref Type: Generic.