Abstract

Isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) were once linked uniformly with hospital-associated infections; however, community-acquired methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) now represents an emerging threat worldwide. To examine the association of differential virulence gene expression with outcomes of human infection, we measured transcript abundance of target staphylococcal genes directly in clinical samples from children with active known or suspected CA-MRSA infections. Virulence genes encoding secreted toxins, including Panton-Valentine leukocidin, were highly expressed during superficial and invasive CA-MRSA infections. In contrast, increased expression of surface-associated Protein A was linked only with invasive disease. Comparisons to laboratory growth of corresponding clinical isolates revealed that tissue-specific expression profiles reflect activity of the staphylococcal regulator Agr during human infection. These results represent the first demonstration of staphylococcal gene expression and regulation directly in human tissue. Such analysis will help to unravel the complex interactions between CA-MRSA and its host environmental niches during disease development.

Keywords: MRSA, PVL, gene regulation, Staphylococcus

Staphylococcus aureus is a persistent human pathogen that is responsible for a range of diseases that vary widely in clinical presentation and severity. The capacity of S. aureus to cause a spectrum of human diseases reflects an ability to adapt to distinct microenvironments in the human body and suggests that the pathogenesis of S. aureus infections is a complex process involving a diverse array of secreted and surface-associated virulence determinants that are coordinately expressed at different stages of infection [1]. Distinct networks of virulence genes are likely activated in response to host signals, including those found in target tissues and those related to innate defenses activated during the infectious process. This expectation manifests in vitro as a growth phase-dependent pattern of virulence determinant expression that is established by global regulatory elements (reviewed in [2]). During exponential growth, the organism synthesizes cell-wall proteins with adhesive functions, including protein A, fibrinogen-binding, fibronectin-binding, and collagen-binding proteins; such expression might augment the initial establishment of colonization in the host. In the transition from exponential to stationary phase, the expression of cell-wall proteins is repressed, while the synthesis of extracellular toxins and enzymes predominates. Through their proteolytic activities and toxic effects on host cells, these exotoxins might facilitate local invasion and dissemination during infection.

The transition from exponential to stationary-phase protein expression is coordinately controlled by global regulators and the Agr quorum-sensing system [3]. During this transition, secretion of a modified peptide pheromone signals cell density-dependent gene expression via RNAIII, the regulatory effector molecule of the Agr system [4–6], resulting in up-regulation of exoprotein gene expression (e.g., hla, hlb) and down-regulation of cell surface adhesins such as protein A (spa) [7]. While this mechanism establishes temporal regulation in vitro, it also likely contributes to spatial regulation by limiting the expression of target genes to compartments where the signal molecule reaches a high concentration. Evidence of an in vivo role for this regulatory pathway is restricted to animal models of S. aureus infection. For example, agr inactivation resulted in reduced virulence in experimental staphylococcal musculoskeletal infection models [8, 9]. Recently, Agr-mediated expression of cytolytic peptides by CA-MRSA was shown to be important for human neutrophil lysis and pathogenesis in a murine model of soft-tissue infection [10]. Animal studies have yielded conflicting conclusions regarding the pathogenic importance of PVL [11, 12] but indicate that PVL expression may alter agr expression patterns [12]. Though animal models of staphylococcal infection are valuable tools for relating the contribution of putative virulence factors identified in vitro to pathogenesis, their relevance to clinical disease is inherently limited and may not reflect human-specific adaptive behavior. To address this, we identified patients with active community-acquired S. aureus infections and defined bacterial gene expression profiles directly in tissue from multiple forms of human infection.

METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture

S. aureus was grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB; BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD). Overnight cultures were inoculated from a frozen stock of the original S. aureus strain isolated on 5% sheep blood agar plates (BD Biosciences) by the Clinical Bacteriology Laboratory at St. Louis Children’s Hospital (SLCH). Fresh broth was inoculated with the overnight culture (1:100 dilution) and incubated at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm). There were no observable differences in the growth rates of the various S. aureus strains in TSB. Therefore, for gene expression analyses, strains were cultured to the transition from the exponential to the stationary phase (OD600=1.0) of growth and harvested immediately for RNA isolation. For comparison to mid-exponential phase gene expression, a subset of strains were grown to an OD600=0.30 in TSB.

Isolation of RNA from infected human tissue

Patients presenting to the SLCH Emergency Department with cutaneous infections suspected to represent CA-MRSA and requiring abscess drainage were identified by Emergency Department staff. No patient had a clinical history suggestive of immune deficiency. Written informed consent was obtained from the parent or guardian, and assent was obtained from the child when appropriate; guidelines of the US Department of Health and Human Services and of the Washington University Human Research Protection Office (HRPO) were followed for all human studies. Upon abscess drainage, a routine sample of abscess contents was collected and transported to the SLCH Clinical Bacteriology Laboratory for aerobic culture as part of routine diagnostics (see Supplementary Table 2). In addition, a second aliquot of purulent material was collected using a sterile syringe or a second sterile swab. Samples were immediately submerged and retained in 2 ml of bacterial RNA stabilization reagent (RNeasy Protect Bacteria; Qiagen, Valencia, CA) in glass vials that had previously been heated to 240°C for at least 4 h to prevent RNase contamination. Samples were incubated at room temperature for approximately 5 minutes and stored at 4°C for 1–96 hours. It was determined experimentally that this range of storage times did not significantly affect RNA stability (data not shown). Samples were centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000×g and the supernatant was carefully removed. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (RLT, Qiagen) and lysates were further homogenized with a FastPrep FP120 reciprocal shaking device and a commercially available extraction reagent, lysing matrix B (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH). Total RNA was isolated by silica membrane binding (RNeasy, Qiagen), and contaminating chromosomal DNA was removed by DNase treatment (Qiagen). Absence of DNA was confirmed by PCR, and the quality and quantity of RNA were determined by spectrophotometry and agarose gel electrophoresis. Criteria for inclusion in downstream applications were OD260/280 > 2.0 and the absence of visible degradation. The yield of total RNA varied but was typically 1–3 μg per sample. A similar procedure was used to isolate total RNA from material collected during operative drainage of subperiosteal abscesses. In all, 78 patients were enrolled; 15 were excluded because their abscess cultures did not grow S. aureus, and 20 were excluded because the isolated RNA was insufficient for analysis.

Interaction of S. aureus with human PMNs in vitro

In accordance with a protocol approved by the HRPO, polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs, or neutrophils) were isolated from the venous blood of healthy volunteers as described previously [13]. Briefly, dextran sedimentation of erythrocytes was followed by Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque Plus; GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) and hypotonic lysis of contaminating erythrocytes. PMN viability was > 99% as assessed by trypan blue exclusion, and purity was > 99% as determined by visualization of nuclear morphology after staining (Hema3; Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Cells were resuspended in pre-warmed RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) buffered with 10 mM HEPES (RPMI/H, pH 7.2) at a concentration of 107 cells/ml and used immediately. To measure S. aureus gene expression during in vitro PMN encounters, bacteria were grown to the exponential-stationary phase transition (OD600=1.0) in TSB, washed once in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in RPMI/H to a concentration of approximately 109 cfu/ml. The S. aureus (~108 cfu) were combined with either PMNs (107 cells) or media only in wells of a 24-well tissue culture plate and centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C. Plates were transferred to a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2 for 60 minutes. The cells from each well were collected in RLT lysis buffer (Qiagen). The lysates were homogenized and total RNA was isolated as described above.

Analysis of S. aureus gene expression

For analysis of transcript levels in infected human tissue, cDNA was prepared from isolated RNA with random primers and SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. In most cases, 50–100 ng of cDNA was used as template for TaqMan real-time PCR performed with an ABI 7500Fast thermocycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). To compare transcript levels in vitro, the S. aureus strain isolated from each patient was cultured as described above and total RNA was isolated from approximately 109 cells in RLT buffer (Qiagen) as described for the in vivo samples. Approximately 100 ng of cDNA from in vitro samples was used as template for TaqMan real-time PCR. For all samples, transcript abundance was normalized to the abundance of the endogenous control gene rrsA. This gene was selected from several candidates because of the documented stability of rrsA expression and mRNA in a variety of conditions [14] as well as the comparable efficiency of the rrsA PCR reaction with the reagents and conditions used in these studies. Relative target expression was calculated according to the Δ(ΔCt) method as described [15], where the fold-change in expression is equal to 2−Δ(ΔCt). Data are presented as the fold-change in transcript abundance in infected human tissue relative to the broth-cultured S. aureus clinical isolate in the indicated calibrator condition and represent the mean and standard deviation of replicate assays. The in vivo samples were analyzed in triplicate; for in vitro samples, triplicate assays were performed with RNA prepared from each of at least two independent cultures. Primers and probes were purchased from a commercial vendor (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA). Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 3 and were designed using available genomic sequence and Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems).

Assays for molecular typing of S. aureus clinical isolates

The results of molecular typing assays are summarized in Table 1; detailed results for each strain are reported in Supplementary Table 1. Total DNA was extracted from staphylococci grown on agar plates by silica membrane binding (QIAamp DNA, Qiagen) and used as an amplification template for PCR based assays with primers described in Supplementary Table 3. The accessory gene regulator (agr) allele group was determined as previously described [16] with primers designed to amplify specific agr alleles. The presence of bsaB, lukS-PV, lukF-PV, and arcA of the arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME) originally identified in a USA300 isolate of S. aureus [17] was detected with allele-specific primers. In addition to Taq DNA polymerase and reaction buffer (Invitrogen), the reaction contained the following: deoxyribonucleotides (200 μM final, each), MgCl2 (2 mM final), and oligonucliotide primers (500 nM final, each). Amplification was carried out under the following conditions: an initial 5 minute denaturation step at 95°C followed by 25 cycles (30 seconds of denaturation at 95°C, 30 seconds of annealing at 55°C, and 1 minute of extension at 72°C) and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 minutes. For methicillin-resistant isolates, the SCCmec allotype was determined by PCR as described elsewhere [18].

Table 1.

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDY PATIENTS AND CUTANEOUS ISOLATES

| Number (Percentage) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 21 (53%) |

| Female | 19 (47%) | |

| Race | African-American | 24 (60%) |

| Caucasian | 14 (35%) | |

| Other | 2 (5%) | |

| Age (years) | Mean | 5.52 |

| Median | 2.53 | |

| Interquartile range | 1.43 – 11.76 | |

| Site of infection | Buttocks/groin | 16 (40%) |

| Lower extremity | 10 (25%) | |

| Head/neck | 5 (13%) | |

| Trunk | 5 (13%) | |

| Upper extremity | 4 (10%) | |

| Methicillin resistance | MRSA | 33 (83%) |

| MSSA | 7 (17%) | |

| Clindamycin resistancea | Susceptible | 33 (83%) |

| Inducible resistance | 4 (10%) | |

| Resistant | 3 (7%) | |

| Agr typeb | I | 38 (95%) |

| II | 2 (5%) | |

| Virulence factorsc | PVL positive | 40 (100%) |

| Bacteriocin positive | 33 (83%) | |

| ACME positive | 31 (78%) |

D-tests for inducible clindamycin resistance were performed on 30 isolates that were erythromycin resistant and clindamycin sensitive by simple disk diffusion.

Molecular typing of the agr locus was determined as described in Methods.

The presence of genes encoding indicated virulence factors was determined as described in Methods.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 4.03 for Windows (San Diego, CA). The Wilcoxon Signed Rank test was used to determine statistical significance for expression differences of target genes in the experimental condition relative to the calibrator condition. The Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison of target gene expression in different experimental conditions. For comparison of in vitro and in vivo gene expression profiles, the log-transformed values for fold change in expression of individual genes in each data set were plotted in the x (in vitro) and y (in vivo) dimensions, and the best-fit straight line was determined by the least-squares method as described previously [19]. The Pearson correlation coefficient, R, is reported for selected experiments.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The prevalence of community-acquired S. aureus infections, coupled with accessibility of infected tissue in typical cutaneous disease, provided a unique opportunity to develop methods for direct analysis of gene expression during human infection. Table 1 summarizes the patients and corresponding cutaneous S. aureus isolates used in this study (see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 for additional details). While the patient population was diverse, the staphylococcal isolates were comparatively homogeneous and representative of circulating CA strains. Phenotypic and genotypic analysis of these strains showed that all 40 cutaneous isolates encoded PVL. Furthermore, 33 (83%) of the strains were methicillin resistant and contained the type IV SCCmec cassette, and 32 (80%) were similar to USA300, the clone causing the majority of CA-MRSA infections in the United States [17, 20].

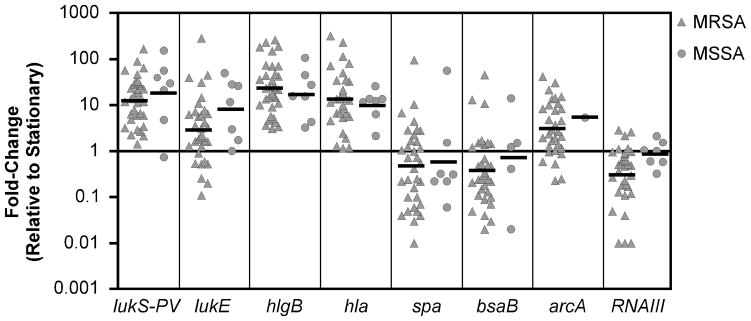

To profile the transcriptional pattern of virulence gene expression of S. aureus during human infection, we used real-time RT-PCR to quantify selected virulence gene transcripts directly in material evacuated from cutaneous abscesses of enrolled patients. Target genes chosen for analysis included several characterized S. aureus virulence factors as well as putative CA-MRSA virulence factors, namely lukS-PV (a component of PVL), arcA (a component of a putative arginine deiminase pathway horizontally acquired from commensal staphylococci [17]), bsaB (an enzyme in a bacteriocin biosynthesis pathway [21]), hlgB (γ-toxin), hla (α-toxin), lukE (leukocidin), spa, and RNAIII. We first compared the abundance of target gene transcripts in each cutaneous abscess sample to that in the corresponding S. aureus strain in stationary-phase broth culture, a condition where many virulence genes are maximally expressed in vitro [3]. The cutaneous abscess profile was characterized by relative up-regulation of genes encoding components of several cytolytic toxins, including PVL (i.e., lukS-PV, lukE, hlgB, hla), and a relative decrease in RNAIII, bacteriocin (bsaB), and protein A (spa) gene expression (Fig. 1). When analyzed separately, there was no significant difference between MRSA and MSSA expression patterns (Fig. 1). The individual cutaneous abscess samples displayed similar trends in differential gene expression, although there was variation in magnitude of the changes among samples. In addition to possible strain-specific differences, inherent variability in human samples (e.g., abscess size, time post infection, host factors) likely contributed to the range of transcript abundance measured in different samples.

Figure 1. Expression of virulence genes in human cutaneous infection.

Expression of putative virulence genes during growth in human tissue and in laboratory broth culture was determined by TaqMan real-time PCR. Data represent the fold-change in normalized transcript abundance for each gene in material collected from a cutaneous abscess relative to the corresponding S. aureus strain grown aerobically to early stationary phase in tryptic soy broth. Data for each of the 40 strains described in Table 1 are represented, and the target gene is specified below the panel; MRSA ( ) and MSSA (

) and MSSA ( ) strains are shown, and the geometric mean for each gene is indicated with a bar. Error bars were generally obscured by the symbol and were omitted for clarity. Differences in transcript abundance between these two groups were not statistically significant. The difference between the cutaneous samples and the stationary samples were statistically significant (P<0.01) for all genes except spa.

) strains are shown, and the geometric mean for each gene is indicated with a bar. Error bars were generally obscured by the symbol and were omitted for clarity. Differences in transcript abundance between these two groups were not statistically significant. The difference between the cutaneous samples and the stationary samples were statistically significant (P<0.01) for all genes except spa.

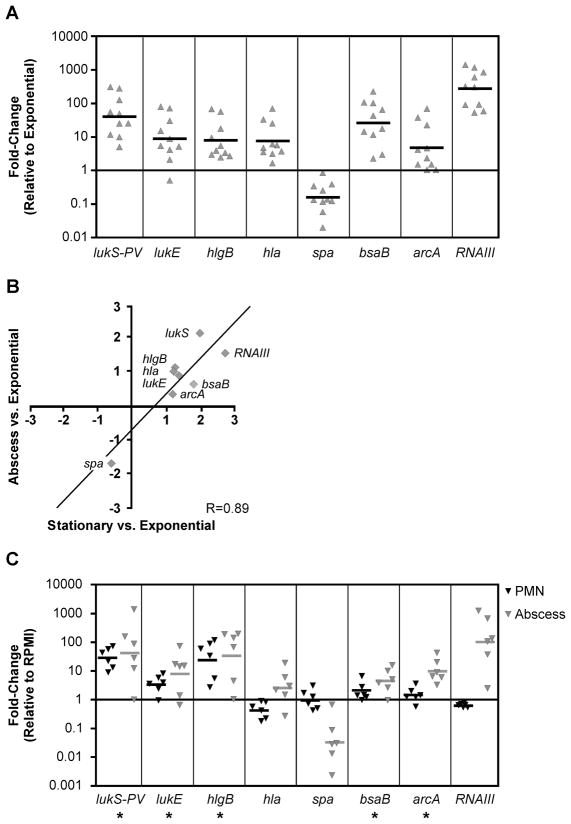

To elucidate the underlying regulatory mechanisms that established transcript patterns in our human samples, we grew representative S. aureus clinical isolates under a variety of in vitro conditions and identified those conditions promoting gene expression most similar to that in infected tissue. Each of the clinical isolates produced a stationary-phase expression profile consistent with the archetypal growth phase-dependent pattern [3] described above (Fig. 2A; all genes, P<0.002). Furthermore, there was a significant correlation (R=0.89, P<0.003) between relative expression levels observed in cutaneous abscess samples and those in stationary-phase culture, including high expression of RNAIII, when compared to expression in exponential phase (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these data indicate that Agr/RNAIII-mediated virulence gene expression during typical cutaneous infection is recapitulated during stationary-phase growth, but that additional host-specific cues apparently augment this transcriptional program in vivo.

Figure 2. Comparison of gene expression profiles between bacteria taken from human cutaneous infection, stationary phase in vitro culture, and in vitro PMN encounter.

Expression of putative virulence genes during growth in human tissue and in vitro was determined by TaqMan real-time PCR. (A) Data represent the fold-change in transcript abundance for each gene in a subset of the S. aureus clinical isolates shown in Figure 1 grown aerobically to early stationary phase in tryptic soy broth ( ) relative to abundance in bacteria grown aerobically to mid-exponential phase in tryptic soy broth. Ten representative strains were chosen for this analysis, and target genes are specified below each panel. The geometric mean for each gene is indicated with a bar. The difference between the stationary sample and the exponential sample was statistically significant (P<0.002) for all genes. (B) The log-transformed average fold-change of target gene expression for the strains shown in panel A grown to stationary phase (x-axis) or in a human cutaneous abscess (y-axis) relative to mid-exponential phase expression is shown. There is a significant correlation (R=0.89; P<0.003) between the tissue and stationary-phase expression profiles. (C) The cutaneous abscess expression [

) relative to abundance in bacteria grown aerobically to mid-exponential phase in tryptic soy broth. Ten representative strains were chosen for this analysis, and target genes are specified below each panel. The geometric mean for each gene is indicated with a bar. The difference between the stationary sample and the exponential sample was statistically significant (P<0.002) for all genes. (B) The log-transformed average fold-change of target gene expression for the strains shown in panel A grown to stationary phase (x-axis) or in a human cutaneous abscess (y-axis) relative to mid-exponential phase expression is shown. There is a significant correlation (R=0.89; P<0.003) between the tissue and stationary-phase expression profiles. (C) The cutaneous abscess expression [ ; Abscess] or expression in the corresponding strain during in vitro encounter with human PMN (▼; PMN) is shown relative to expression of each gene in a media-only control condition (RPMI; see Materials and Methods for details). Five representative strains were chosen for this analysis, and the geometric mean for each gene is indicated with a bar. The majority of the genes showed a similar direction of differential regulation (denoted by asterisks), but there was a poor correlation (R=0.44) between the tissue and PMN expression profiles.

; Abscess] or expression in the corresponding strain during in vitro encounter with human PMN (▼; PMN) is shown relative to expression of each gene in a media-only control condition (RPMI; see Materials and Methods for details). Five representative strains were chosen for this analysis, and the geometric mean for each gene is indicated with a bar. The majority of the genes showed a similar direction of differential regulation (denoted by asterisks), but there was a poor correlation (R=0.44) between the tissue and PMN expression profiles.

A common feature of cutaneous infections caused by S. aureus is the presence of neutrophil-rich purulent fluid [1]. We hypothesized that exposure to polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN, or neutrophils) might contribute to the expression profile of S. aureus at this site of infection. To evaluate the influence of PMN-specific signals, we compared the abundance of selected transcripts during in vitro encounters with purified human PMN versus that within human cutaneous abscesses. Previous analysis of the global expression profile of S. aureus during in vitro phagocytic interaction with human PMN revealed a pathogen survival transcriptional pattern characterized by the up-regulation of genes involved in capsule synthesis, oxidative stress, and virulence [22]. Consistent with these findings [11, 22], expression of toxins known to target leukocytes, including PVL, was increased in vitro in the presence of PMN relative to a time-matched control in media alone (Fig. 2C; PMN: lukS-PV, lukE, hlgB), and the relative abundance of the RNAIII transcript was decreased (Fig. 2C; PMN: RNAIII). Compared with expression in human cutaneous infection, PMN-derived expression was similar in direction for 5 of the 8 genes analyzed (Fig. 2C; Abscess), and there was a strong correlation of the two profiles for only one of the strains (R= 0.83, 0.65, 0.37, 0.27, 0.11, −0.24). These data suggest that this in vitro model of host-pathogen interaction is insufficient to represent the influence of host-specific cues for S. aureus virulence gene expression in human cutaneous infection.

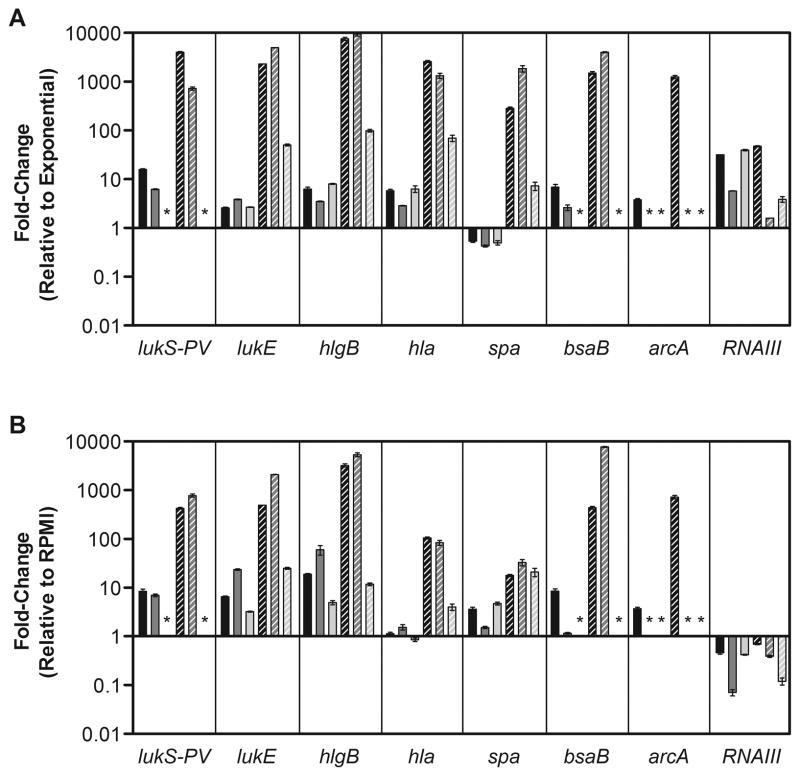

Community-acquired S. aureus is associated with a broad range of observed disease severity in otherwise healthy patients, yet the host and bacterial factors promoting superficial versus invasive staphylococcal disease are not understood. It has been hypothesized that changes in bacterial virulence gene expression in response to tissue-specific or temporal cues in vivo play an important role in determining the outcome of infection. The in vivo production of virulence factors in inferred by specific humoral and cell-mediated immune responses to infection in humans [23], and the localization and kinetics of pathogen gene expression have been investigated in animal models of bacterial infection [2], but direct measurement of expression in human infections has not been previously reported. We therefore determined the abundance of target transcripts in material collected from patients with community-acquired invasive (subperiosteal) abscesses caused by S. aureus for comparison to the cutaneous abscess samples. As in cutaneous abscesses, expression of exotoxin genes in invasive abscess samples was significantly higher than that in stationary phase (Fig. 3A; compare invasive abscess to stationary, P<0.05). RNAIII was present in the invasive abscess samples at a level comparable to the corresponding strain grown to stationary phase (Fig. 3A; RNAIII), but, in comparison to the cutaneous samples (Fig. 2A; RNAIII), was not as highly expressed. Another difference in the invasive profile was the sharp elevation of spa expression compared to stationary phase (Fig. 3A; spa). An increase in spa expression in conditions with reduced RNAIII abundance is consistent with in vitro transcriptional regulation [3], and the high level of spa transcription in these samples suggests that protein A might play an important role in dissemination or survival during invasive infections in general, as has been suggested in staphylococcal pneumonia [24]. The invasive-disease expression profiles were strongly correlated with those of S. aureus in PMN encounters (R=0.86, 0.79, 0.90; P<0.01), suggesting that decline of RNAIII abundance and increased spa expression could reflect the influence of PMN interaction (Fig. 3B; compare invasive abscess to PMN).

Figure 3. Expression of virulence genes during invasive human infection.

Expression of putative virulence genes during growth in human tissue and in vitro was determined by TaqMan real-time PCR. (A) Data represent the fold-change in transcript abundance for each gene in material collected from an invasive human subperiosteal abscess (striped bars) or the corresponding S. aureus strain grown aerobically to early stationary phase in tryptic soy broth (solid bars) relative to the strain grown aerobically to mid-exponential phase in tryptic soy broth. For each target gene indicated below the panel, each of three strains is represented by a different shaded bar, and an asterisk indicates that the gene is not present in that strain. The difference between the invasive abscess samples and the stationary phase samples was statistically significant (P<0.05) for all genes except RNAIII. (B) The invasive abscess expression (striped bars) or expression of the corresponding strain during an in vitro encounter with human PMN (solid bars) is shown relative to expression of each gene in a media-only control condition (RPMI; see Materials and Methods for details). Axis and symbols are as described for panel A. As indicated in the text there was a significant correlation between the invasive abscess profile and the PMN profile for all three strains (R=0.86, 0.79, 0.90; P<0.01).

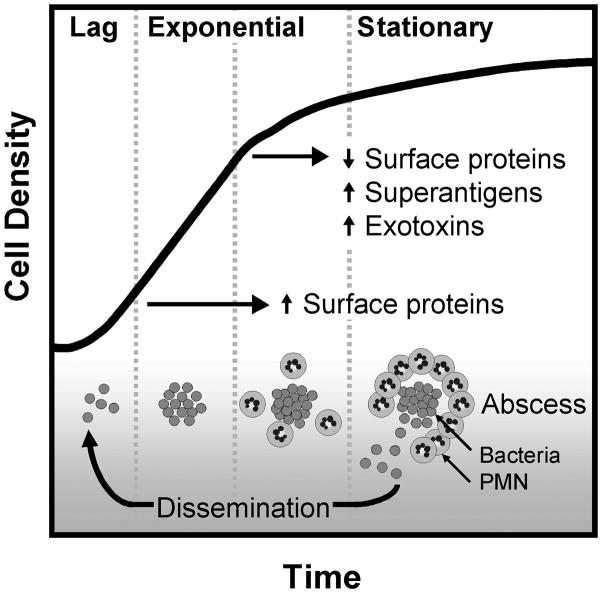

Our data are therefore consistent with a model of CA-MRSA infection in which the organism interprets host site-specific signals, including cues related to the influx of PMN, to modulate Agr-regulated expression of virulence determinants in vivo (Fig. 4). Extension of this approach will optimize the establishment of in vitro correlates for in vivo conditions, previously advanced in animal models of Gram-positive infection [25]. The methodology described herein will also represent a worthwhile approach for interrogation of newly identified CA-MRSA virulence determinants in human infections. Our findings highlight the importance of understanding gene expression and regulation in the endeavor to determine the mechanisms of CA-MRSA virulence and in the development of anti-infective strategies to combat this emerging pathogen.

Figure 4.

A schematic representation of the relationship between growth phase and disease progression with regard to virulence gene expression is shown. The paradigm of regulation in broth culture is well established; our data provide in vivo support for a proposed correspondence [2] between this in vitro paradigm and the regulation of virulence factor expression within the human host.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Clinical Bacteriology Laboratory at Saint Louis Children’s Hospital for providing the S. aureus clinical isolates and for assistance with molecular typing of the strains; E. Epplin for assistance with patient enrollment and molecular typing of the strains; and the students of the Washington University Pediatric Emergency Medicine Research Associate Program for assistance with patient enrollment.

FUNDING

This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health grant K08-DK067894, an NRSA Institutional Research Training Grant (T32-HD007507), the Washington University (WU) Child Health Research Center (K12-HD01487), the WU Infectious Diseases Scholars Program, and the W. M. Keck Postdoctoral Program in Molecular Medicine.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

PRESENTATION OF DATA

This information was presented, in part, at the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory meeting on Microbial Pathogenesis and Host Response, Cold Spring Harbor, NY, September 2007.

References

- 1.Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199808203390806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheung AL, Bayer AS, Zhang G, Gresham H, Xiong YQ. Regulation of virulence determinants in vitro and in vivo in Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2004;40:1–9. doi: 10.1016/S0928-8244(03)00309-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Novick RP. Autoinduction and signal transduction in the regulation of staphylococcal virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2003;48:1429–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novick RP, Ross HF, Projan SJ, Kornblum J, Kreiswirth B, Moghazeh S. Synthesis of staphylococcal virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory RNA molecule. EMBO J. 1993;12:3967–75. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lyon GJ, Mayville P, Muir TW, Novick RP. Rational design of a global inhibitor of the virulence response in Staphylococcus aureus, based in part on localization of the site of inhibition to the receptor-histidine kinase, AgrC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13330–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lina G, Jarraud S, Ji G, et al. Transmembrane topology and histidine protein kinase activity of AgrC, the agr signal receptor in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:655–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Novick RP, Jiang D. The staphylococcal saeRS system coordinates environmental signals with agr quorum sensing. Microbiology. 2003;149:2709–17. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26575-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung AL, Eberhardt KJ, Chung E, et al. Diminished virulence of a sar-/agr- mutant of Staphylococcus aureus in the rabbit model of endocarditis. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:1815–22. doi: 10.1172/JCI117530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdelnour A, Arvidson S, Bremell T, Ryden C, Tarkowski A. The accessory gene regulator (agr) controls Staphylococcus aureus virulence in a murine arthritis model. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3879–85. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3879-3885.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang R, Braughton KR, Kretschmer D, et al. Identification of novel cytolytic peptides as key virulence determinants for community-associated MRSA. Nat Med. 2007;13:1510–4. doi: 10.1038/nm1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Voyich JM, Otto M, Mathema B, et al. Is Panton-Valentine leukocidin the major virulence determinant in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus disease? J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1761–70. doi: 10.1086/509506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Labandeira-Rey M, Couzon F, Boisset S, et al. Staphylococcus aureus Panton-Valentine leukocidin causes necrotizing pneumonia. Science. 2007;315:1130–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1137165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parkos CA, Delp C, Arnaout MA, Madara JL. Neutrophil migration across a cultured intestinal epithelium. Dependence on a CD11b/CD18-mediated event and enhanced efficiency in physiological direction. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1605–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI115473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anderson KL, Roberts C, Disz T, et al. Characterization of the Staphylococcus aureus heat shock, cold shock, stringent, and SOS responses and their effects on log-phase mRNA turnover. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6739–56. doi: 10.1128/JB.00609-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−Δ ΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lina G, Boutite F, Tristan A, Bes M, Etienne J, Vandenesch F. Bacterial competition for human nasal cavity colonization: role of Staphylococcal agr alleles. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:18–23. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.1.18-23.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diep BA, Gill SR, Chang RF, et al. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2006;367:731–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68231-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elizur A, Orscheln RC, Ferkol TW, et al. Panton-Valentine Leukocidin-positive methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus lung infection in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest. 2007;131:1718–25. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho KH, Caparon MG. Patterns of virulence gene expression differ between biofilm and tissue communities of Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol Microbiol. 2005;57:1545–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, et al. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:666–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahl HG, Bierbaum G. Lantibiotics: biosynthesis and biological activities of uniquely modified peptides from Gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:41–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Voyich JM, Braughton KR, Sturdevant DE, et al. Insights into mechanisms used by Staphylococcus aureus to avoid destruction by human neutrophils. J Immunol. 2005;175:3907–19. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.6.3907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferry T, Thomas D, Perpoint T, et al. Analysis of superantigenic toxin Vbeta T-cell signatures produced during cases of staphylococcal toxic shock syndrome and septic shock. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:546–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.01975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomez MI, Lee A, Reddy B, et al. Staphylococcus aureus protein A induces airway epithelial inflammatory responses by activating TNFR1. Nat Med. 2004;10:842–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loughman JA, Caparon M. Regulation of SpeB in Streptococcus pyogenes by pH and NaCl: a model for in vivo gene expression. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:399–408. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.2.399-408.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.