Abstract

The transient receptor potential channel melastatin member 8 (TRPM8) is expressed in sensory neurons, where it constitutes the main receptor of environmental innocuous cold (10–25 °C). Among several types of G protein-coupled receptors expressed in sensory neurons, Gi-coupled α2A-adrenoreceptor (α2A-AR), is known to be involved in thermoregulation; however, the underlying molecular mechanisms remain poorly understood. Here we demonstrated that stimulation of α2A-AR inhibited TRPM8 in sensory neurons from rat dorsal root ganglia (DRG). In addition, using specific pharmacological and molecular tools combined with patch-clamp current recordings, we found that in heterologously expressed HEK-293 (human embryonic kidney) cells, TRPM8 channel is inhibited by the Gi protein/adenylate cyclase (AC)/cAMP/protein kinase A (PKA) signaling cascade. We further identified the TRPM8 S9 and T17 as two key PKA phosphorylation sites regulating TRPM8 channel activity. We therefore propose that inhibition of TRPM8 through the α2A-AR signaling cascade could constitute a new mechanism of modulation of thermosensation in both physiological and pathological conditions.

Keywords: Cell/Neuron, Channels/Calcium, G Proteins/Coupled Receptors (GPCR), Phosphorylation/Kinases/Serine-Threonine, Receptors/Membrane, Signal Transduction/G-proteins

Introduction

The members of the transient receptor potential (TRP)5 superfamily of cationic channels display diverse activation mechanisms and participate in a plethora of physiological and pathological processes (1), which made them the focus of intense research over the last decades. A number of TRPs, dubbed thermo-TRPs, from TRPV (vanilloid), TRPM (melastatin), and TRPA (ankyrin) subfamilies can be activated by various ambient temperatures ranging from noxious cold to noxious heat. They also respond to chemical imitators of temperatures and to a number of chemical and environmental irritants (2). No wonder that with such activating stimuli, virtually all thermo-TRPs are implicated in nociception and pain transduction (3, 4).

So far, the best known and characterized temperature-gated TRP channels are TRPV1, activated by noxious heat (>42 °C) (2), and TRPM8, activated by innocuous cold (<25 °C) (5). Capsaicin, the active constituent of hot chili pepper, mimics the sensation of heat via TRPV1 activation, while the peppermint oil component, menthol, causes a cooling sensation, via TRPM8 gating (2). Except for the innocuous cold and menthol, TRPM8 can be also activated by some other cooling agents such as icilin and eucalyptol as well as by non-cooling compounds hydroxy-citronellal, geraniol, and linalool (6). It has been shown that the mechanism of TRPM8 activation by cold and menthol involves a negative shift in the channel voltage-dependent opening from very positive non-physiological membrane potentials toward physiological values (7, 8).

TRPM8 is expressed in the subset of dorsal root ganglion (DRG) and trigeminal sensory neurons in which it acts as a cold receptor (5, 9). Recently, using TRPM8 knock-out mice, three independent groups have established that TRPM8 is indeed the principal detector of environmental cold (10–12). TRPM8-deficient mice have severe deficits in avoiding cold temperatures and in paw withdrawal responses to acetone and icilin, suggesting that TRPM8 activation mediates generation of an unpleasant signal sent to the brain. Moreover, the expression of TRPM8 is increased in neuropathic pain models. However, the consequences of such increases may depend on the nature of the pain and pain condition. Indeed, enhanced TRPM8 expression in the rat model of chronic constriction injury of sensory nerves (CCI) induces hyperexcitability of menthol- and cold-sensitive neurons to innocuous cold, which underlies the mechanism of cold allodynia (13, 14). On the other hand, TRPM8 activation also mediates analgesic effects to the more noxious stimuli, as TRPM8 agonists are known to suppress mechanical and heat nociception in CCI animals (15). The analgesic effect of TRPM8 activation was suggested, though, to involve central metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) and glutamate release from TRPM8-containing afferents exerting an inhibitory gate control over nociceptive inputs (15).

Among several types of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) expressed in sensory neurons, Gi-coupled α2A-adrenoreceptor (α2A-AR) is known to be involved in analgesia response after nerve injury and in thermoregulation (16, 17). Moreover, α2A-AR is central to the antinociceptive action of the clinically used α2A-AR agonist, clonidine. Antinociceptive effect of α2A-AR activation becomes much more pronounced following peripheral nerve injury (18). Given that the molecular target of α2A-AR-mediated antinociception is not well understood and that CCI animal model is associated with 1) up-regulated TRPM8 expression, 2) gain in TRPM8-mediated cold allodynia, and 3) increased α2A-AR-mediated antinociception, we reasoned that there might be a mechanistic link between α2A-AR and TRPM8, through which α2A-AR can negatively control TRPM8 function under conditions of its overexpression.

Thus, the purpose of our work was to investigate whether α2A-AR can modulate TRPM8 activity, and if so, what signaling pathway is involved. Our results show that stimulation of α2A-AR inhibits TRPM8 in sensory neurons from rat DRG. Based on heterologous expression of various components of the α2A-AR-to-TRPM8 pathway in HEK-293 cells, employment of specific pharmacological and molecular tools combined with patch-clamp recording of the whole-cell TRPM8 currents, we show that this effect is mediated via Gi protein coupled to the inhibition of the AC/cAMP/PKA pathway. Resulting decreases in the PKA-dependent phosphorylation of TRPM8 reduce normal channel activity. Thus, in this work we propose a novel physiological mechanism regulating TRPM8 channel activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cells and Electrophysiology

HEK-293 cells stably transfected with human TRPM8 (HEK-293M8) were cultured as described previously (19), and TRPM8 expression was induced with tetracycline 24 h before the start of the experiments (20). The composition of the normal extracellular solution used for electrophysiological recordings was (in mm): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 0.3 Na2HPO4, 0.4 KH2PO4, 4 NaHCO3, 5 glucose, 10 HEPES (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH). Patch-clamp pipettes were filled with an intracellular solution containing (in mm): 140 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2.5 CaCl2, 4 EGTA, 10 HEPES (calculated free Ca2+ concentration: 150 nm, pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH).

Neurons were isolated from the lumbar DRG of adult Wistar rats (250–300 g) using an enzymatic digestion procedure described elsewhere (21). The cell suspension was plated onto Petri dishes filled with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 8 μg/ml gentamicine and incubated for up to 18–24 h at 37 °C in the 95% air 5% CO2 atmosphere prior to using them in electrophysiological experiments. During whole-cell patch-clamp recordings, DRG neurons were bathed in the standard extracellular solution (in mm): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, pH 7.4, while dialyzed with Cs-based intracellular patch-pipette solution to minimize background outward currents (in mm): 140 CsCl, 5 EGTA, 10 HEPES, 2 Mg-ATP, 0.5 Li-GTP, pH adjusted to 7.3 with Cs(OH).

Whole-cell patch-clamp experiments on DRG neurons and HEK-293M8 cells were performed using Axopatch 200B amplifier and pClamp 9.0 software (Molecular Devices, Union City, CA) for data acquisition and analysis. Patch pipettes for the whole-cell recordings were fabricated from borosilicate glass capillaries (World Precision Instr., Inc., Sarasota, FL) on horizontal puller (Sutter Instruments Co., Novato, CA) and had a resistance of 3–5 MΩ for HEK-293 cells or 2–3 MΩ for DRG neurons when filled with intracellular solutions.

In the course of patch-clamp recording, drugs, and solutions were applied to the cells using temperature-controlled microperfusion system (Cell MicroControls, Norfolk, VA) with common outflow of the multiple solution lines, which was placed in close proximity (∼200 μm) to the studied cell. Membrane currents through TRPM8 channels (ITRPM8) were activated by a temperature drop from 33 to 20 °C (cold), icilin (10 μm), or menthol (500 μm or 100 μm in the event of DRG neurons) and monitored by applying every 3 s, voltage-clamp pulses that consisted of an initial 200-ms depolarization to +100 mV, enabling full current activation followed by descending ramp (rate 0.4 mV/ms) to −100 mV (see Fig. 6A). The ramp portion of the current served to construct the I-V relationship.

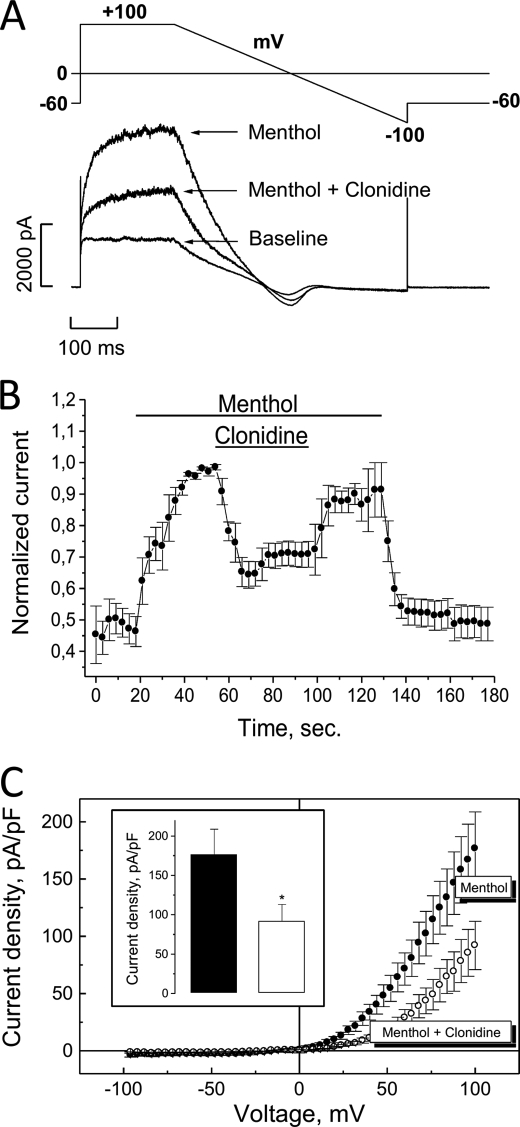

FIGURE 6.

Functional link between α2A-AR and TRPM8 in native rat DRG neurons. A, representative tracings of the baseline current in DRG neurons and currents in the presence of menthol (100 μm) before and after exposure to clonidine (30 μm) at room temperature. B, averaged time courses of menthol-activated ITRPM8 and effect on it of clonidine in 5 clonidine-responsive neurons; current was measured at +100 mV and normalized to the maximal value for each neuron (mean ± S.E., n = 5). C, averaged I-V relationships of menthol-activated ITRPM8 before (black circles) and after (open circles) exposure to clonidine (mean ± S.E., n = 5); inset shows quantification of the effects of clonidine on the density of menthol-activated ITRPM8 at +100 mV. (*) denotes statistically significant differences with p < 0.05.

Plasmids and Transfections

α2A-Adrenoreceptor subtype constructs are kind gifts from Prof. Lutz Hein (Institute of Pharmacology and Toxicology, University of Freiburg, Germany) and Prof. Stephen Lanier (Department of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA). Constructs of the wild type, constitutively activated (Q205L), and constitutively inactivated (G204A) forms of Gi are kind gifts from Dr. Sylvie Hermouet (Laboratoire d'Hématologie, Institut de Biologie, CHU de Nantes, France).

HEK-293M8 were co-transfected with 2 μg of each construct and 0.4 μg of pmax GFP using a NucleofectorTM (Amaxa, Gaithersburg, MD). Cells were used for patch-clamp experiments 24 h after nucleofection.

Drugs and Chemicals

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich except for icilin, which was from Tocris. The final concentration of ethanol and DMSO in the experimental solution did not exceed 0.1%.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed with Clampfit 9.0 and Origin 5.0 (Microcal Software Inc., Northampton, MA). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E. Overall statistical significance was determined by analysis of variance (ANOVA). In the case of significance, differences between the means of two groups were analyzed by unpaired Student's t test, while multiple comparisons between groups were performed by ANOVA tests followed by Dunnett tests unless otherwise indicated. p < 0.05 was considered significant. The statistical analyses were performed using the InStat v3.06 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). All results presented in this article are representative of two or three experiments.

Mutagenesis

The five putative PKA phosphorylation sites predicted for the human TRPM8 sequence by the prediction tool pkaPS described (22) were mutated into “inactive” alanines and constitutively “active” aspartic acids. Ten mutants were therefore generated by in vitro mutagenesis in the hTRPM8pcDNA4 plasmid (19) using the primers shown in Table 1 (QuikChange Site-directed Mutagenesis kit, Agilent Technologies-Stratagene products).

TABLE 1.

Primers used for the in vitro mutagenesis of TRPM8

| Mutant | Mutagenesis primer 5′–3′a |

|---|---|

| S9A | CGGGCAGCCAGGCTCGCCATGAGGAACAGAAGG |

| S9D | CGGGCAGCCAGGCTCGACATGAGGAACAGAAGG |

| T17A | GAAGGAATGACGCTCTGGACAG |

| T17D | GGAACAGAAGGAATGACGATCTGGACAGCACCCGG |

| T32A | CGCGTCTCGGAGCGCAGACTTGTCTTACAG |

| T32D | GCGCGTCTCGGAGCGACGACTTGTCTTACAGTG |

| S121A | AGTATATACGTCTGGCCTGCGACACGGACGCGG |

| S121D | GTATATACGTCTGGACTGCGACACGGACGCGG |

| S367A | CCCGCACGGTGGCCCGGCTGCCTGAGG |

| S367D | CCCGCACGGTGGACCGGCTGCCTGAGG |

a Characters in bold represent the nucleotides that were mutated.

RESULTS

Stimulation of α2A-Adrenoreceptor Inhibits TRPM8 Function

To test for functional coupling between α2A-adrenoreceptors and TRPM8 channel, both of which were implicated in antinociception and cold hypersensitivity, we used HEK-293 cell line stably expressing human TRPM8 (HEK-293M8), which was created in our laboratory (20), in addition transiently transfected with α2A α2-adrenoreceptor subtype (HEK-293M8-α2A-AR). α2A-AR was activated by the agonist clonidine, and TRPM8 functionality was assessed by the ability to generate membrane current (ITRPM8) in response to cold, menthol, or icilin.

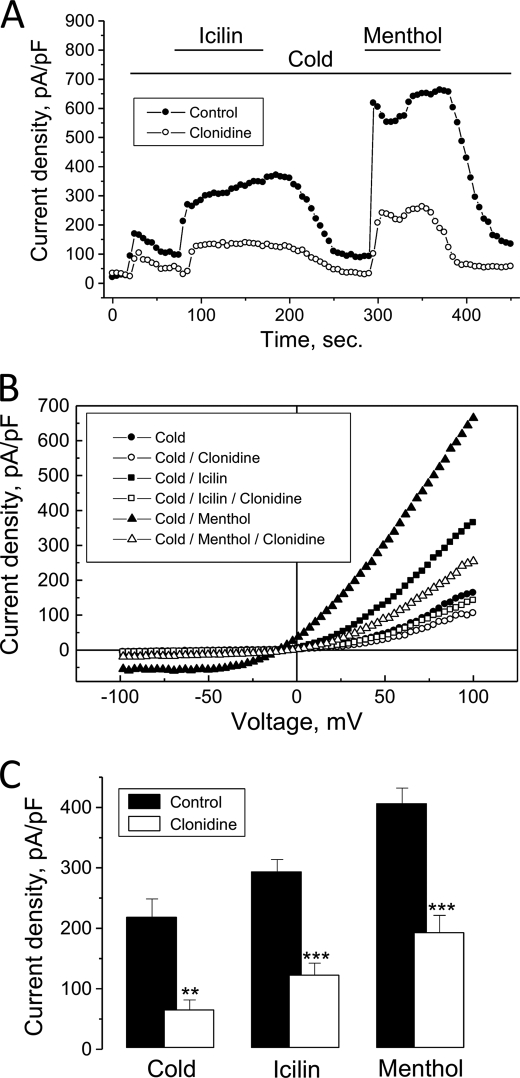

As documented in Fig. 1, A–C, incubation of HEK- 293M8-α2A-AR cells with clonidine (10 μm) for 10–20 min resulted in the decrease of ITRPM8 density in response to the three major TRPM8-activating stimuli, cold (temperature drop from 33 to 20 °C), icilin (10 μm), and menthol (500 μm), by 70 ± 7%, 58 ± 6% and 52 ± 7%, respectively, compared with the cells, which were not exposed to clonidine. Because the effect of clonidine appeared to be the same when TRPM8-activating stimuli were applied independently (Fig. 1C) or in a successive way (supplemental Fig. S2C), for practical reasons we chose to perfuse cold, icilin, and menthol consecutively for the next experiments.

FIGURE 1.

Co-expression of α2A-AR with TRPM8 channels in HEK-293 cells induces inhibition of TRPM8-carried current (ITRPM8) by the α2A-adrenergic agonist, clonidine. A, representative time courses of ITRPM8 (measured as current density at +100 mV) in response to TRPM8-activating stimuli (shown by horizontal bars): temperature drop from 33 to 20 °C (cold), icilin (10 μm), and menthol (500 μm) in HEK-293M8 cells transiently transfected with the α2A subtype of α2-adrenoreceptor (HEK-293M8-α2A-AR) under control conditions (black circles) or following treatment with clonidine (10 μm, open circles). B, I-V plot of A. C, quantification of the inhibitory effect of clonidine in cold-, icilin-, and menthol-activated ITRPM8 in HEK-293M8-α2A-AR cells (mean ± S.E., n = 5–10 for each cell type and condition). Each TRPM8-activating stimulus was applied independently of each other. (**) and (***) denote statistically significant differences with p < 0.02 and p < 0.01, respectively.

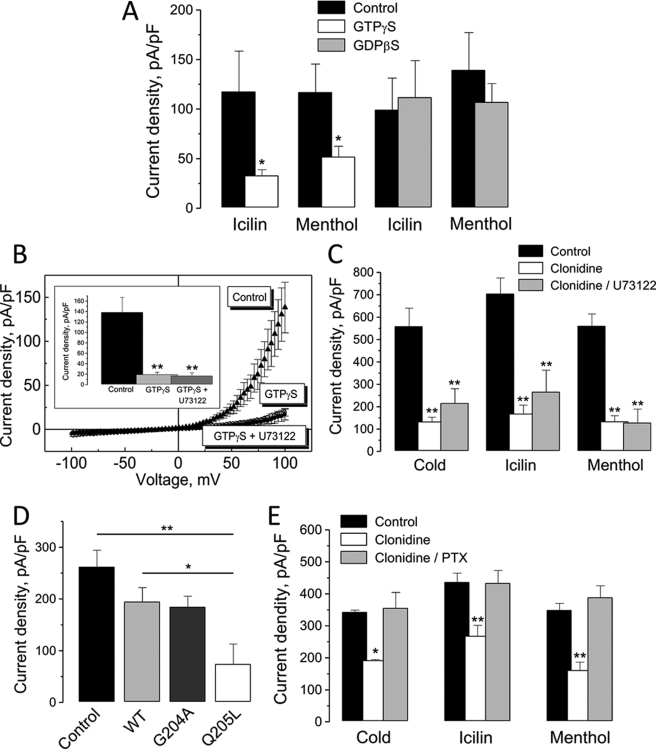

The Inhibitory Effect of α2A-AR Stimulation on TRPM8 Does Not Involve the Gq/PLC Pathway

Because α2-adrenoreceptors act through G proteins, we investigated possible regulation of TRPM8 activity by G proteins activators and inhibitors. To do so, we used non-hydrolyzable GTP analogues, GTPγ-S, which is a constitutive G protein activator, and GDPβ-S, which is G protein inhibitor. Predialysis of HEK-293M8 cells with the intracellular pipette solution supplemented with GTPγ-S (100 μm) attenuated their responsiveness to icilin and menthol, respectively, by 72 ± 5% and 55 ± 9% (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, inclusion in the pipette solution of GDPβ-S (100 μm) did not impair ITRPM8 activation by both icilin and menthol, strongly suggesting the involvement of G proteins in TRPM8 inhibition.

FIGURE 2.

Functional link between α2A-AR and TRPM8 involves Gi proteins, but not Gq proteins and PLC. A, quantification of the effects of HEK-293M8 cell dialysis with the constitutive G protein activator, GTPγ-S (100 μm, white columns) and inhibitor, GDP-β-S (100 μm, gray columns), on icilin- and menthol-activated ITRPM8 (mean ± S.E., n = 6–10 for each cell type and condition). B, average ramp-derived I-V relationships of menthol-activated ITRPM8 in HEK-293M8 cells dialyzed with GTPγ-S-free (black triangles) and GTPγ-S-containing pipette solution with (black circles) and without (open circles) cell pretreatment with PLC inhibitor, U73122 (1 μm). The inset shows quantification of ITRPM8 densities at + 100 mV under respective conditions (mean ± S.E., n = 6–10 for each condition). C, quantification of the inhibitory effect of clonidine on the density of cold-, icilin-, and menthol-activated ITRPM8 in HEK-293M8-α2A-AR cells pretreated (gray columns) and not pretreated (open columns) with U73122 (mean ± S.E., n = 6–10 for each condition). D, quantification of the effects of HEK-293M8 cell transient transfection with the wild-type (WT, light gray column), constitutively activated (Q205L, open column) or constitutively inactivated (G204A, gray column) forms of the Gi α-subunit on menthol-activated ITRPM8 densities; black column represents HEK-293M8 blank plasmid-transfected control (mean ± S.E., n = 6–10 for each cell type). E, quantification of the effects of clonidine on the density of cold-, icilin-, and menthol-activated ITRPM8 in HEK-293M8-α2A-AR cells pretreated (gray columns) and not pretreated (open columns) with Gi inhibitor, PTX (500 ng/ml, mean ± S.E., n = 6–10 for each condition). On all graphs (*) and (**) denote statistically significant differences to control or between connected values with p < 0.05 and p < 0.02, respectively.

α2A-ARs are generally known to be coupled to the inhibitory Gi proteins (23) through which they inhibit AC activity, although there is evidence of the possibility of α2A-AR coupling to the Gq proteins as well (24). In the latter case, one can expect stimulation of catalytic activity of PLC, which hydrolyzes phospholipids. Noteworthy, depletion of phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate (PIP2), which is an important TRPM8 regulator and PLC substrate, during PLC stimulation has been shown to induce ITRPM8 rundown (25, 26). In view of potential coupling of α2A-ARs to the Gq/PLC pathway, we next focused on assessing its involvement in the signal transduction from α2A-AR to TRPM8. For that we used the PLC inhibitor, U73122.

In the first set of experiments, we pretreated HEK-293M8 cells with U73122 (1 μm) and then dialyzed them with GTPγ-S-supplemented (100 μm) intracellular pipette solution during patch-clamp recording. Cell dialysis with GTPγ-S strongly blocked ITRPM8 activation by menthol, irrespective of whether or not they were pretreated with U73122 (Fig. 2B), indicating that PLC and consequently Gq most likely are not involved in ITRPM8 abolition by constitutive G proteins activation with GTPγ-S. Next, to validate no involvement of the Gq/PLC pathway in the clonidine effects, we pretreated HEK-293M8-α2A-AR cells with the drug (10 μm) alone or in combination with U73122 (1 μm). As quantified in Fig. 2C, suppression of PLC by U73122 did not impair the inhibitory action of clonidine on ITRPM8, activated by cold, icilin, or menthol, showing that stimulation of α2A-ARs does not recruit the Gq/PLC pathway in signal transduction to TRPM8.

The Inhibitory Effect of Clonidine Involves Gi Proteins and the Adenylate Cyclase Pathway

To determine whether clonidine- and GTPγ-S-induced inhibition of TRPM8 occurs via Gi proteins, we have transfected HEK-293M8 cells with one of three forms of Gi α-subunit: wild type (Gαi2wt), constitutively activated (Gαi2Q205L), or constitutively inactivated (Gαi2G204A). Comparison of menthol-evoked ITRPM8 densities in these cells at +100 mV has shown that only in the cells transfected with constitutively activated Gαi2Q205L the density of ITRPM8 dropped to the level comparable to that achieved during intracellular infusion of GTPγ-S via patch pipette (Fig. 2D). Other forms of Gαi2 (i.e. wild-type and inactivated), although produced some decrease of ITRPM8 density compared with the control (i.e. cells with no transfection of any of the Gαi2-s), this decrease was far less than the one caused by the transfection of constitutively activated Gαi2Q205L (Fig. 2D). The fact that the inhibitory effect of GTPγ-S can be mimicked by the constitutively activated form of Gαi2 strongly suggests the involvement of Gi proteins in signal transduction from α2A-ARs to the TRPM8 channel.

To further confirm this conclusion we also conducted experiments with the specific Gi inhibitor, pertussis toxin (PTX). As documented in Fig. 2E, overnight preincubation of HEK-293M8-α2A-AR cells with PTX (500 ng/ml) completely abolished the inhibitory effects of clonidine (10 μm) on ITRPM8 irrespective of whether it was activated by cold, icilin, or menthol. Taken together, both results, with Gαi2Q205L transfection and PTX treatment, unequivocally demonstrate that α2A-ARs exert inhibition of TRPM8 activity via Gi proteins.

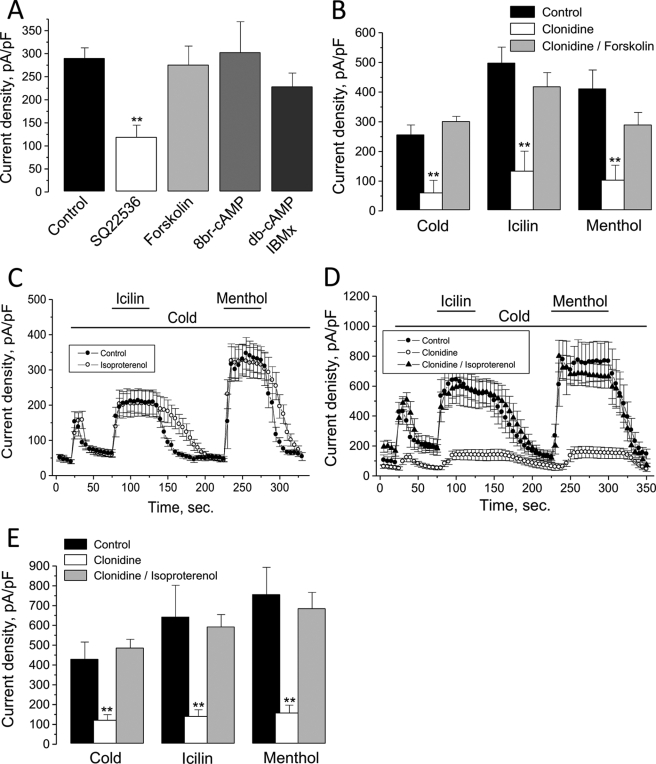

Because Gi proteins inhibit the catalytic activity of AC, which catalyzes cAMP production, the Gi-mediated suppression of TRPM8 can be the consequence of decreased levels of intracellular cAMP and a concomitant reduction in PKA-dependent phosphorylation of TRPM8 channels or accessory protein(s) impairing TRPM8 activity. To test this hypothesis, we used a number of pharmacological agents, which influence the AC-cAMP-PKA signaling pathway: AC activator, forskolin, AC inhibitor, 9-(tetrahydro-2-furanyl)-9H-purin-6-amine (SQ22536), cell membrane-permeable cAMP analogs, 8-bromo-cAMP (8Br-cAMP), and dibutyryl cAMP (db-cAMP) as well as the phosphodiesterase inhibitor 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine (IBMX). The results of the respective experiments are summarized in Fig. 3A. As one can see, 15-min long pretreatments of HEK-293M8 cells with forskolin (10 μm), 8Br-cAMP (1 mm), or a combination of db-cAMP (1 mm) and IBMX (100 μm) did not affect menthol-activated ITRPM8, whereas pretreatment with SQ22536 (200 μm) caused its decrease by 59 ± 9%. Moreover, despite the fact that the incubation with forskolin per se did not influence the baseline ITRPM8, it totally removed the inhibitory effect of clonidine (10 μm) on cold-, icilin-, and menthol-activated currents (Fig. 3B). Antagonistic influence on clonidine effects similar to that of forskolin could also be attained with the β-adrenoreceptor (β-AR) agonist, isoproterenol. Endogenous β-ARs, which are coupled via stimulatory Gs proteins to AC, are known to be present in HEK-293 cells (e.g. (27)). Thus, if forskolin stimulates AC directly, then isoproterenol does the same via Gs-coupled β-AR. Fig. 3, C–E show that preapplication of isoproterenol (1 μm) per se did not influence the baseline level of ITRPM8 in HEK-293M8-α2A-AR cells, but almost completely abrogated inhibitory effects of clonidine.

FIGURE 3.

α2A-AR and TRPM8 are linked via AC and cAMP pathway. A, quantification of the effects of HEK-293M8 cells pretreatment with AC inhibitor, SQ22536 (200 μm, open column), AC activator, forskolin (10 μm, light gray column), cell membrane-permeable cAMP analog, 8Br-cAMP (1 mm, gray column), or a combination of db-cAMP (1 mm) and phosphodiesterase inhibitor, IBMX (100 μm, dark gray column) on menthol-activated ITRPM8 (mean ± S.E., n = 6–22 for each condition). B, quantification of the inhibitory effect of clonidine on the density of cold-, icilin-, and menthol-activated ITRPM8 in HEK-293M8-α2A-AR cells pretreated (gray columns) and not pretreated (open columns) with forskolin (mean ± S.E., n = 6–10 for each condition). C, averaged time courses of ITRPM8 (measured as current density at +100 mV) in response to TRPM8-activating stimuli (shown by horizontal bars) in the control HEK-293M8 cells (black circles) and HEK-293M8 cells pretreated with β-adrenoreceptor agonist, isoproterenol (1 μm, open circles) (mean ± S.E., n = 6 for each condition). D, same as in C, but for HEK-293M8-α2A-AR cells under control conditions (black circles) and following treatment with clonidine (open circles) and clonidine plus isoproterenol (black triangles) (mean ± S.E., n = 6 for each condition). E, quantification of the effects of clonidine alone (open columns) and in combination with isoproterenol (gray columns) on the density of cold-, icilin-, and menthol-activated ITRPM8 (at + 100 mV) in HEK-293M8-α2A-AR (mean ± S.E., n = 6–10 for each condition). On all graphs (*) and (**) denote statistically significant differences to control with p < 0.05 and p < 0.02, respectively.

These results indicate that enhancement of intracellular cAMP levels either by stimulation of AC or by providing exogenous cAMP together with inhibition of its degradation has no consequence on TRPM8 function, whereas decrease of cAMP levels results in TRPM8 inhibition. They also show that enhancement of cAMP above the basal level due to direct or β-AR/Gs protein-mediated stimulation of AC prevents the effectiveness of clonidine. Altogether they are consistent with the general notion that stimulation of α2A-ARs by clonidine brings about Gi-mediated inhibition of AC and reduction of intracellular cAMP levels below the basal levels, which is the causative reason for TRPM8-reduced activity.

TRPM8 Ser-9 and Thr-17 PKA Phosphorylation Sites Are Critical in the Clonidine-induced Channel Inhibition

Because reduction of intracellular cAMP levels inhibits TRPM8 activity, the next logical step was to determine whether this molecular sequence of events involves PKA.

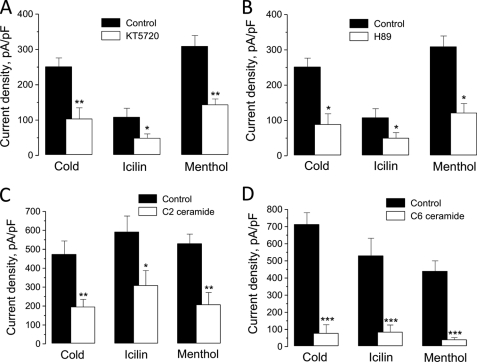

In the first set of experiments, we assessed this issue by using a pharmacological approach. Fig. 4, A and B shows that pretreatment of HEK-293M8 cells with each of the two membrane-permeable PKA inhibitors, KT5720 (1 μm) or H-89 (10 μm), reduced dramatically cold-, icilin-, and menthol-activated ITRPM8. Moreover, significant inhibition of cold-, icilin-, and menthol-activated ITRPM8 could be also attained by pretreatment of HEK-293M8 cells for 2 h with either C6 or C2 ceramide (each at 10 μm), which are activators of the serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), dephosphorylating the PKA phosphorylation sites (Fig. 4, C and D). TRPM8 inhibition following α2A-AR stimulation with clonidine is therefore due to a decrease in PKA activity.

FIGURE 4.

Functional link between α2A-AR and TRPM8 is mediated via PKA-dependent phosphorylation. A and B, quantification of the effects of HEK-293M8 cells pretreatment with PKA inhibitors, KT5720 (1 μm, A) or H-89 (10 μm, B), on the density of cold-, icilin-, and menthol-activated ITRPM8 in HEK-293M8 cells (mean ± S.E., n = 5–8 for each condition). C and D, same as in A and B, but for the activators of the serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2A, C2 (10 μm, C) and C6 (10 μm, D) ceramide (mean ± S.E., n = 8 for each condition). On all graphs (*), (**), and (***) denote statistically significant differences to control with p < 0.05, p < 0.02, and p < 0.01, respectively.

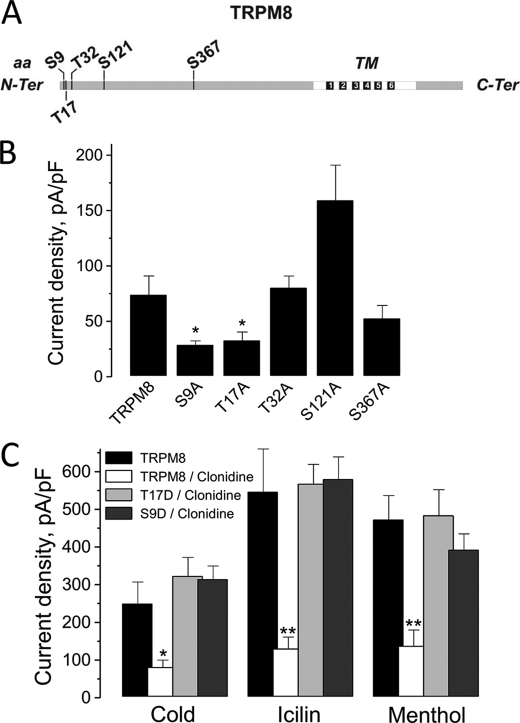

The latter suggests the presence of PKA phosphorylation sites in the TRPM8 sequence. Indeed five putative PKA phosphorylation sites were predicted in the channel N-terminal cytosolic tail: Ser-9, Thr-17, Thr-32, Ser-121, and Ser-367 (Fig. 5A). To test hypothetical sites, we proceeded to a substitution of these serines or threonines by alanines (inactive mutants), or by aspartic acids (constitutively active mutants). Subsequently, mutants were screened by an electrophysiological approach using icilin, because icilin is the most specific and potent agonist of TRPM8 (28). Alanine substitution of the Thr-32, Ser-121, and Ser-367 sites had no consequence on TRPM8 sensitivity to icilin, whereas mutation of the Ser-9 and Thr-17 sites inhibited the icilin-induced TRPM8 current by ∼40% (Fig. 5B). The constitutively active mutants did not present any statistical difference in their activity compared with the native TRPM8 (data not shown). In addition, we tested the sensibility of S9D and T17D to clonidine, because inactivation of these sites elicited less current than the native form of TRPM8. S9D and T17D mutations totally abolished the inhibitory effect of α2A-AR stimulation by clonidine on the three main TRPM8 activators (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these results demonstrated that the Ser-9 and Thr-17 PKA phosphorylation sites of TRPM8 are involved in the clonidine-induced inhibition of the channel.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of the mutation of TRPM8 PKA phosphorylation sites on the channel activity. A, schematic representation of TRPM8 protein sequence and its putative PKA phosphorylation sites. B, histogram summarizing icilin-activated ITRPM8 (measured as current density at +100 mV) in HEK-293 cells transfected with TRPM8 (TRPM8) or the mutants S9A, T17A, T32A, S121A, and S367A (mean ± S.E., n = 10–15 for each condition). C, histogram summarizing densities of cold-, icilin-, and menthol-activated ITRPM8 in HEK-293 cells transfected with TRPM8 (TRPM8) or mutants S9D and T17D in the presence or absence of clonidine (mean ± S.E., n = 5–8 for each condition). On all graphs (*) and (**) denote statistically significant differences to control with p < 0.05 and p < 0.02, respectively.

Inhibitory Effect of α2A-AR Stimulation on TRPM8 Activity in DRG Neurons

Following the establishment of the functional coupling between α2A-AR and TRPM8 in a heterologous system, we next tested whether α2A-AR agonist, clonidine, can modulate endogenous TRPM8-mediated membrane current (ITRPM8) in native DRG neurons. These neurons were enzymatically isolated from male rats and subjected to the whole-cell patch-clamp recording at room temperature. Almost all tested DRG neurons of small diameter developed significant membrane current in response to the application of menthol (100 μm). As this current showed pronounced outward rectification, close to 0 mV reversal potential and rapidly diminished upon menthol withdrawal, properties similar to those reported for the activation of endogenous and heterologously expressed TRPM8 (5, 9), it was identified as ITRPM8. In all experiments in DRG neurons, ITRPM8 was isolated by subtracting the baseline current before application of menthol from the net current in the presence of menthol (see Fig. 6A).

Exposure of the DRG neurons that showed menthol-activated ITRPM8 to clonidine (30 μm) caused decrease of the current amplitude (measured at +100 mV) only in about 20% of the neurons tested (in 5 of 23). In those neurons, the average reduction of ITRPM8 in response to clonidine reached 48 ± 12% (at + 100 mV, n = 5, Fig. 6, A–C). We have noted that neurons, which responded to clonidine by ITRPM8 inhibition, were characterized by significantly lower baseline density of ITRPM8 (176 ± 32 pA/pF, n = 5) compared with the unresponsive neurons (429 ± 83 pA/pF, n = 18), suggesting that apparently only the subpopulation of DRG neurons with low density ITRPM8 coexpress TRPM8 and α2A-AR. Overnight treatment of the neurons with PTX completely abolished the effect of clonidine (data not shown, n = 20). The result with PTX indicates that consistent with the findings in heterologous expression system (i.e. HEK-293M8-α2A-AR cells) in native DRG neurons, which show clonidine effect, functional coupling between α2A-ARs and TRPM8 is realized with the involvement of Gi proteins.

It is worthy to note that menthol is also an agonist of the TRPA1 channel expressed in small DRG neurons (29, 30). However, there are several characteristic features of the mode of menthol action on TRPA1 that could be used to discriminate between TRPM8- and TRPA1-mediated menthol responses in sensory neurons. After washout of menthol, TRPA1 currents decay slowly (τ > 20 s) in contrast to the virtually immediate reversal of the effect of menthol on TRPM8 (τ < 2 s) (29). In all menthol-responsive neurons demonstrating in this study menthol washout caused virtually immediate decreases in the current amplitude (Fig. 6B), suggesting that menthol sensitivity of these neurons was mediated by TRPM8 expression. Further, after washout of menthol (concentrations > 30 μm), TRPA1 currents exhibit a characteristic transient increase in amplitude. In our study, we have never observed such increases in the current amplitudes after washout of menthol.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified a novel signaling pathway for physiological regulation of the cold/menthol receptor, TRPM8. Our work demonstrates, for the first time, that the activity of the TRPM8 channel can be inhibited through the decreased phosphorylation of the channel itself by cAMP-dependent PKA. Because the extent of PKA-dependent phosphorylation of target proteins is controlled through a number of plasma membrane GPCRs coupled via inhibitory Gi protein to the AC inhibition, this discovery opens up the possibility for alleviating TRPM8-mediated cold hypersensitivity under conditions of its overexpression. In particular, we established a functional link between α2A-ARs and TRPM8 in sensory neurons utilizing the Gi/AC/cAMP/PKA pathway, which may underlie the known analgesic significance of these receptors in nerve injury and in thermoregulation.

Our experiments on freshly isolated sensory DRG neurons from male rats have shown pronounced inhibition of menthol-stimulated TRPM8 activity by α2A-AR agonist, clonidine. We have detected clonidine effects on TRPM8-mediated membrane current in ∼20% of menthol-sensitive neurons, which in view of generally small subpopulation of menthol-sensitive neurons (∼10%, (31)) and low reported expression of α2A-AR in DRGs (32) can be explained by even smaller proportions of DRG neurons coexpressing both TRPM8 and α2A-AR.

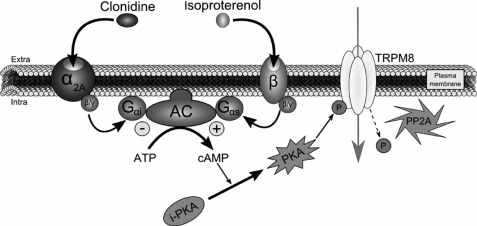

Although the α2A-ARs mostly signal via the Gi/AC cascade (23), there is also evidence that they may recruit the Gq/PLC pathway as well (24). In the event of α2A-AR-mediated TRPM8 inhibition, the involvement of the Gq/PLC pathway would be most anticipated, as the substrate of PLC activity, PIP2, is a well-known TRPM8-modulating agent whose depletion during PLC activation causes ITRPM8 rundown (25, 26). However, our experiments with the PLC inhibitor, U73122, did not support the hypothesis on Gq/PLC involvement, as this agent failed to impair in any essential way the inhibitory effects of clonidine on TRPM8 heterologously coexpressed with α2A subtype of α2-AR in HEK-293 cells. At the same time, using molecular and pharmacological tools and a mutagenesis strategy affecting different stages of Gi/AC/cAMP/PKA pathway (i.e. constitutively active and inactive forms of Gαi, Gi/Go proteins inhibitor, PTX, AC activator, forskolin, AC inhibitor, SQ22536, membrane-permeable cAMP analog, db-cAMP, phosphodiesterase inhibitor, IBMX, PKA inhibitors, KT5720 and H-89, phosphatase 2A activators, ceramide C6 and C2, phospho-null, and phospho-mimicked mutants) strongly interfered with the action of clonidine on TRPM8, consistent with the notion that α2A-AR regulates TRPM8 through the decrease of cAMP/PKA-dependent phosphorylation. This inhibitory pathway is summarized in the scheme in Fig. 7. Interestingly, either forskolin, isoproterenol, or a combination of db-cAMP/IBMX, the interventions that stimulate cAMP-dependent phosphorylation, did not affect the baseline menthol-activated ITRPM8, suggesting that the basal level of TRPM8 phosphorylation is sufficient to maintain the fully functional state of the channel. To the contrary, all interventions, which led to the decreased phosphorylation via the Gi/AC/cAMP/PKA cascade, mimicked the effects of clonidine through the receptor. This indicates that the physiological meaning of such regulation may consist in counteracting enhanced expression of TRPM8 that may be associated with some pathological states.

FIGURE 7.

Schematic depiction of TRPM8 regulation by α2A- and β-adrenoreceptors. α2A-AR stimulation by clonidine initiates a sequence of intracellular events as follows: Gαi protein activation following clonidine fixation on α2A-AR leads to AC inhibition and decrease of cAMP production. By consequence, PKA transition from an inactive (i-PKA) to an active (PKA) form is reduced. In parallel, the intracellular serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) dephosphorylates TRPM8 Ser-9 and Thr-17 inhibiting the channel activity. This inhibitory pathway can be abolished by stimulation of β-AR with isoproterenol, because it would lead to a stimulation of the Gαs protein coupled to this receptor and to an up-regulation of the adenylate cyclase activity. The subsequent increase in cAMP concentration would potentiate PKA phosphorylation, which will fully maintain the functional activity of TRPM8.

Indeed, our study suggests that TRPM8 current reduction through α2A-AR could have an impact in nociception, notably in cold allodynia during CCI, a condition characterized by the increased expression of TRPM8 in the subpopulation of nociceptive DRG neurons leading to the gain of a painful cold sensitivity (14). Interestingly, under the CCI condition, the expression of α2A-AR in DRG neurons increases as well (16). We therefore propose that overexpression and stimulation of α2A adrenergic receptors in sensory neurons may represent protective measures, leading to an attenuation of the painful symptoms of allodynia, such as hypersensitivity to cold temperatures, via the inhibition of TRPM8 channel activity.

TRPM8 regulation through the Gi/AC/cAMP/PKA pathway discovered herein may have significance far beyond the α2A-AR- and TRPM8-mediated sensory transduction and antinociception, as TRPM8 is known to be present in a number of tissues outside the peripheral nervous system including common types of human cancers (e.g. (6)), in which it can be coexpressed with other GPCRs coupled to the same signaling pathway. Moreover, if for any reason cAMP/PKA-dependent phosphorylation is compromised and TRPM8 function is reduced, one can expect that its functionality can be restored via Gs-coupled GPCRs or other influences that stimulate AC activity. Interestingly, just recently it has been shown that lowering of ER Ca2+ stores content, independently of the cytosolic Ca2+, leads to the recruitment of AC, accumulation of cAMP and PKA activation, the process dubbed store-operated cAMP signaling or SOcAMPS (33). This opens up additional Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 (iPLA2)/lysophospholipids (LPLs) (34) mechanisms for up-regulation of TRPM8 by store-mobilizing factors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. S. Hermouet for the Gi constructs and Prof. Lutz Hein and Prof. Stephen Lanier for the α2A-AR constructs.

This work was supported by grants from INSERM, la Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer, le Ministère de l'Éducation Nationale, la Région Nord/Pas-de-Calais, and INTAS 05-1000008-8223.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S2 and Figs. S1 and S2.

- TRP

- transient receptor potential

- α2A-AR

- α2A-adrenoreceptor(s)

- AC

- adenylate cyclase

- PKA

- cAMP-dependent kinase

- ISO

- isoproterenol

- TRPM8

- TRP melastatin 8

- DRG

- dorsal root ganglion

- ITRPM8

- current through TRPM8 channel

- HEK-293M8

- human embryonic kidney 293 cells stably transfected with human TRPM8

- HEK-293M8-α2A-AR

- HEK-293 cells transiently transfected with α2A-AR construct

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- PTX

- pertussis toxin

- GTPγ-S

- guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)triphosphate

- GDPγ-S

- guanosine 5′-3-O-(thio)diphosphate

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- CCI

- chronic constriction injury

- 8Br-cAMP

- 8-bromo-cAMP

- db-cAMP

- dibutyryl cAMP

- IBMX

- 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- PLC

- phospholipase C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Venkatachalam K., Montell C. (2007) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 387–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clapham D. E. (2003) Nature 426, 517–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cortright D. N., Krause J. E., Broom D. C. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1772, 978–988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang H., Woolf C. J. (2005) Neuron 46, 9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKemy D. D., Neuhausser W. M., Julius D. (2002) Nature 416, 52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Voets T., Owsianik G., Nilius B. (2007) Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 179, 329–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brauchi S., Orio P., Latorre R. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 15494–15499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Voets T., Droogmans G., Wissenbach U., Janssens A., Flockerzi V., Nilius B. (2004) Nature 430, 748–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peier A. M., Moqrich A., Hergarden A. C., Reeve A. J., Andersson D. A., Story G. M., Earley T. J., Dragoni I., McIntyre P., Bevan S., Patapoutian A. (2002) Cell 108, 705–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bautista D. M., Siemens J., Glazer J. M., Tsuruda P. R., Basbaum A. I., Stucky C. L., Jordt S. E., Julius D. (2007) Nature 448, 204–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colburn R. W., Lubin M. L., Stone D. J., Jr., Wang Y., Lawrence D., D'Andrea M. R., Brandt M. R., Liu Y., Flores C. M., Qin N. (2007) Neuron 54, 379–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dhaka A., Murray A. N., Mathur J., Earley T. J., Petrus M. J., Patapoutian A. (2007) Neuron 54, 371–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung M. K., Caterina M. J. (2007) Neuron 54, 345–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xing H., Chen M., Ling J., Tan W., Gu J. G. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 13680–13690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Proudfoot C. J., Garry E. M., Cottrell D. F., Rosie R., Anderson H., Robertson D. C., Fleetwood-Walker S. M., Mitchell R. (2006) Curr. Biol. 16, 1591–1605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Birder L. A., Perl E. R. (1999) J. Physiol. 515, 533–542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Höcker J., Paris A., Scholz J., Tonner P. H., Nielsen M., Bein B. (2008) Anesthesiology 109, 95–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duflo F., Li X., Bantel C., Pancaro C., Vincler M., Eisenach J. C. (2002) Anesthesiology 97, 636–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thebault S., Lemonnier L., Bidaux G., Flourakis M., Bavencoffe A., Gordienko D., Roudbaraki M., Delcourt P., Panchin Y., Shuba Y., Skryma R., Prevarskaya N. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 39423–39435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck B., Bidaux G., Bavencoffe A., Lemonnier L., Thebault S., Shuba Y., Barrit G., Skryma R., Prevarskaya N. (2007) Cell Calcium 41, 285–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinchenko V. O., Kostyuk P. G., Kostyuk E. P. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1724, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neuberger G., Schneider G., Eisenhaber F. (2007) Biol. Direct 2, 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramos B. P., Stark D., Verduzco L., van Dyck C. H., Arnsten A. F. (2006) Learn Mem. 13, 770–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conklin B. R., Chabre O., Wong Y. H., Federman A. D., Bourne H. R. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 31–34 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu B., Qin F. (2005) J. Neurosci. 25, 1674–1681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohács T., Lopes C. M., Michailidis I., Logothetis D. E. (2005) Nat. Neurosci. 8, 626–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takezawa R., Schmitz C., Demeuse P., Scharenberg A. M., Penner R., Fleig A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6009–6014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chuang H. H., Neuhausser W. M., Julius D. (2004) Neuron 43, 859–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karashima Y., Damann N., Prenen J., Talavera K., Segal A., Voets T., Nilius B. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 9874–9884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao B., Dubin A. E., Bursulaya B., Viswanath V., Jegla T. J., Patapoutian A. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 9640–9651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Madrid R., Donovan-Rodríguez T., Meseguer V., Acosta M. C., Belmonte C., Viana F. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 12512–12525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho H. J., Kim D. S., Lee N. H., Kim J. K., Lee K. M., Han K. S., Kang Y. N., Kim K. J. (1997) Neuroreport 8, 3119–3122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lefkimmiatis K., Srikanthan M., Maiellaro I., Moyer M. P., Curci S., Hofer A. M. (2009) Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 433–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanden Abeele F., Zholos A., Bidaux G., Shuba Y., Thebault S., Beck B., Flourakis M., Panchin Y., Skryma R., Prevarskaya N. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 40174–40182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.