Abstract

Cytochrome P450 enzymes are versatile catalysts involved in a wide variety of biological processes from hormonal regulation and antibiotic synthesis to drug metabolism. A hallmark of their versatility is their promiscuous nature, allowing them to recognize a wide variety of chemically diverse substrates. However, the molecular details of this promiscuity have remained elusive. Here, we have utilized two-dimensional heteronuclear single quantum coherence NMR spectroscopy to examine a series of mutants site-specific labeled with the unnatural amino acid, [13C]p-methoxyphenylalanine, in conjunction with all-atom molecular dynamics simulations to examine substrate and inhibitor binding to CYP119, a P450 from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. The results suggest that tight binding hydrophobic ligands tend to lock the enzyme into a single conformational substate, whereas weak binding low affinity ligands bind loosely in the active site, resulting in a distribution of localized conformers. Furthermore, the molecular dynamics simulations suggest that the ligand-free enzyme samples ligand-bound conformations of the enzyme and, therefore, that ligand binding may proceed largely through a process of conformational selection rather than induced fit.

Keywords: Computer Modeling, Cytochrome P450, NMR, Protein Conformation, Protein Structure, UV Spectroscopy, Xenobiotics

Introduction

Recently, the dynamic nature of enzymes has drawn much attention (1–3). Protein dynamics are not only important for ligand recognition and binding, but also for bringing catalytic residues in close proximity to the bound substrate so that a reaction can occur (4, 5). It has long been known that conformational flexibility is critical for the recognition of a wide variety of substrates and inhibitors by the human liver drug-metabolizing cytochrome P450 enzymes (6–9). These enzymes are members of a superfamily of hemoproteins that catalyze oxidative transformations of xenobiotic compounds (10). These “promiscuous” enzymes utilize a conserved mechanism of oxygen activation to oxidize a host of structurally diverse molecules (10). The crystal structures of several human P450 isoforms have recently been obtained, in many cases co-crystallized with known ligands (9, 11–13). In some cases, ligands have been found bound at some distance from the heme iron or even outside the active site (11, 14). These particular structures imply that concerted conformational changes have to take place in the enzyme to position the ligand favorably for oxidation. However, it is not clear how this type of conformational change manifests itself in this important enzyme family. Two competing, albeit not mutually exclusive, theories have emerged to explain how P450s are able to adapt themselves to accommodate such a large number of chemically diverse compounds. The first, a derivative of Koshland's classic induced fit model, relies on substrate binding to induce conformational changes in the enzyme in a stepwise fashion that ultimately advance the ligand into the active site and place it in a productive orientation for oxidation (9, 15–17). The second model, derived from Monod-Wyman-Changeux allostery theory, relies on the idea of conformational selection that presupposes the enzyme exists as a heterogeneous equilibrium population of conformational substates, each with a varying affinity for the external ligand (6, 18, 19). In this view, binding of ligand perturbs the conformational equilibrium, shifting it in favor of the active conformer and thus facilitating further substrate binding events (19, 20). Many lines of evidence support both the induced fit (9, 21, 22) and the conformational equilibrium models (6, 7, 18, 23, 24) for ligand binding to cytochrome P450 enzymes. The challenge, of course, is to design experiments that distinguish between the two models and to determine under what conditions one mechanism is more consistent with the data than the other (24, 25). In the realm of molecular interactions on the picosecond to second timescale, NMR is unrivaled as a technique for the acquisition of both information about the timeframe of conformational transitions and structural resolution at the atomic level (26, 27). NMR is therefore highly appropriate for such studies. Ultimately, a detailed description of the conformational events that occur during ligand binding will prove useful in understanding some of the complex phenomena exhibited by P450 enzymes, such as homo- and heterotropic cooperativity.

Previously, we demonstrated the utility of CYP119, a cytochrome P450 isolated from the thermophilic bacterium Sulfolobus acidocaldarius, as a model for examination of the detailed molecular events involved in binding of the inhibitor 4-phenylimidazole, employing two-dimensional 1H,13C-HSQC2 NMR of the protein tagged with the unnatural amino acid, 13C-labeled p-methoxyphenylalanine ([13C]MeOF) (28). This enzyme undergoes similar conformational transitions to those of its mesophilic mammalian drug-metabolizing counterparts, but it has physical and chemical properties that make it particularly amenable to high resolution two-dimensional NMR investigation (28, 29). In this study, we expand our previous results by investigating the conformational dynamics of CYP119 when binding a weak inhibitory ligand (imidazole) or a tight binding substrate (lauric acid), again using two-dimensional 1H,13C-HSQC NMR spectroscopy with a series of [13C]MeOF-labeled mutants. In conjunction with the two-dimensional NMR experiments, we performed novel long range, all-atom molecular dynamics simulations to interrogate the conformational subspace accessible to the enzyme. The results suggest that tight binding hydrophobic ligands tend to lock the enzyme into a single conformational substate, whereas weak binding low affinity ligands bind loosely in the active site, resulting in a distribution of localized conformers. Furthermore, the molecular dynamics simulations demonstrate the ability of the ligand-free enzyme to sample the ligand-bound conformation, suggesting that ligand binding proceeds predominantly through a process of conformational selection. Ultimately, these studies lay the groundwork for the subsequent application of these techniques to the less tractable human drug-metabolizing P450 isoforms.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Chemicals

Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals and solvents used were of analytical grade and were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Solvents were high performance liquid chromatography grade, and all water used was deionized and distilled in a Milli-Q apparatus.

Synthesis of [13C]MeOF

Moisture-sensitive reactions were performed in flame-dried glassware under a positive pressure of nitrogen or argon. Air- and moisture-sensitive materials were transferred by syringe under an argon atmosphere. N,N-Dimethylformamide was dried over 4-Å molecular sieves for at least 1 week prior to use. K2CO3 was dried in an oven at 150 °C overnight and was then cooled to room temperature under argon. All reactions were magnetically stirred and monitored by TLC using 0.25-mm Alltech precoated silica gel plates. 1H NMR spectra were recorded at 400 MHz on a Varian Gemini spectrometer using tetramethylsilane as the internal reference. Chemical shifts are reported in parts per million (δ), and coupling constants (J values) are given in Hertz (Hz). The following abbreviations are used to explain the multiplicities: s = singlet; d = doublet. LC-MS was performed on a Waters system equipped with an XTerra MS C18 reverse phase column (3.5 μm, 2.1 × 50 mm).

Boc-Tyr(O-13CH3)-OCH3

To a solution of Boc-Tyr-OCH3 (4 g, 13.6 mmol) in anhydrous N,N-dimethylformamide (15 ml) was added anhydrous K2CO3 (4 g, 29 mmol) and [13C]iodomethane (0.944 ml, 14.9 mmol, 1.1 eq). The reaction mixture was stirred under argon at room temperature overnight (16 h), and the completeness of the reaction was monitored by TLC (hexane/EtOAc, 4:1 v/v). The reaction mixture was poured into CH2Cl2 (100 ml) and water (300 ml). The aqueous fraction was further extracted with CH2Cl2 (100 ml × 3). The extracts were combined, washed with water (100 ml), and dried over Na2SO4. After evaporation of the solvent in vacuo, the resulting yellow oil was purified by silica gel flash chromatography (hexane/EtOAc, 4:1 v/v) to give a white solid (3.9 g, 93%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) and LC-MS (ESI+) values matched literature reference values (28).

Boc-Tyr(O-13CH3)-OH

To a solution of Boc-Tyr(O-13CH3)-OCH3 (3.9 g, 12.6 mmol) in methanol (30 ml) was added LiOH (1 n, 20 ml). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 h, and the completeness of the reaction was monitored by TLC (hexane/EtOAc, 2:1 v/v). HCl (1 n) was added to adjust the solution to pH ∼ 5, followed by removal of methanol in vacuo. The residue was taken up in EtOAc (300 ml), washed with saturated NaCl (aqueous), and dried over Na2SO4. Evaporation of the solvent gave the product as a white foamy solid (3.6 g, 97%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) and LC-MS (ESI+) values matched literature reference values (28).

HClδH-Tyr(O-13CH3)-OH

Boc-O13CH3-Tyr-OH (3.6 g, 12.1 mmol) was treated with 25% (v/v) trifluoroacetic acid in CH2Cl2 (45 ml) for 1 h at room temperature. After evaporation of the solvents, the residue was dissolved in 40% methanol/water (100 ml) containing 0.5 n HCl, and the methanol was then removed in vacuo. The aqueous solution was subjected to lyophilization to give a white solid (2.8 g, 100%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.17 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 6.89 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 4.12 (dd, J = 8, 5.2 Hz, 1H), 3.75 (d, J = 144 Hz, 3H), 3.19 (dd, J = 14.4, 5.2 Hz, 1H), 3.04 (dd, J = 14.4, 8 Hz, 1H); LC-MS (ESI+): 197.08 (MH+, 100%) and 180.10 (MH+-NH3, 48%).

Construction of CYP119 Mutants

The CYP119 mutants were constructed using the QuikChange mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Briefly, the forward and reverse oligonucleotides containing the desired TAG stop codon mutation were used to amplify the CYP119-pCWori vector DNA using PCR. DpnI was then used to digest the parental DNA. Transformation of the remaining DNA resulted in colonies that were screened for the particular mutation by DNA sequencing.

Expression and Purification of 13C-labeled CYP119-[13C]MeOF Mutants

Initially, transformed DH10B Escherichia coli containing the unnatural tRNA plasmid pSup-OTyrRS (30) and the CYP119 cDNA plasmid pCWOri+-CYP119-[13C]MeOF (28) were grown overnight in a 50-ml LB starter culture containing 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 50 μg/ml ampicillin. A 5-ml aliquot of this starter culture was then used to inoculate 0.5 liter of Terrific Broth expression medium containing 25 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 100 μg/ml ampicillin. The expression culture was incubated at 37 °C with shaking at 225 rpm until it reached log phase (0.6 A600, 2–4 h). Protein expression was induced by simultaneous addition of 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside and 1 mm [13C]MeOF. The incubation temperature was reduced to 30 °C, and the cultures were allowed to continue to incubate with shaking at 160 rpm for 36 h. The mutant CYP119-[13C]MeOF was purified according to the standard protocol used for CYP119-wt. Briefly, cells were harvested by centrifugation in a Sorvall RC-5B centrifuge at 5,000 rpm and 5 °C for 20 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in 4 volumes (4 ml/g cell paste) of 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 4 mg/ml lysozyme, 16 units/ml DNase, 4 units/ml RNase, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The cells were allowed to stir on ice for 1 h to ensure complete resuspension and promote lysis. Next, the entire resuspension was lysed using a Branson sonicator (3 × 1-min bursts at 50% power, with 1-min cooling in an ice bath between each burst). Cellular debris was separated from recombinant protein by centrifugation in a Sorvall Ultracentrifuge at 100,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The protein-containing supernatant was collected, pooled, and loaded directly onto a pre-equilibrated Q-Sepharose column. The column was washed with ∼10 column volumes of 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, containing 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The protein was eluted with a salt gradient of 0–250 mm NaCl in 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, buffer. All of the reddish fractions were combined and dialyzed overnight against 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, buffer. The protein was then loaded onto a PBE94 column pre-equilibrated with 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, buffer, washed, and eluted with Polybuffer 74 at pH 5.0. CYP119 eluted at ∼pH 6.6. The Polybuffer was removed by precipitation with 80% ammonium sulfate, and the protein was concentrated and stored in 100 mm potassium Pi, pH 7.4, 1 mm EDTA at −80 °C until utilized. The protein was judged to be >90% pure by SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and Gelcode Blue staining. The final protein concentration was determined using the method of Omura and Sato, with an extinction coefficient of E450 = 100 mm−1cm−1. In the absence of [13C]MeOF, no protein was produced.

Ligand Kd Determination Using Optical Difference Spectroscopy

To determine whether or not the CYP119-[13C]MeOF mutant proteins were able to bind ligands in a fashion similar to the wild-type protein, UV-visible difference spectra were acquired for a variety of ligands using a dual beam OLIS/Aminco DW2a spectrophotometer (OLIS, Bogart, GA). Both sample and reference chamber contained 1 ml of 0.5 μm CYP119-[13C]MeOF in 100 mm potassium Pi, pH 7.4. Prior to initiating the titration, a baseline was recorded between 350 and 500 nm. Subsequently, 1-μl aliquots of a concentrated stock solution of ligand were added to the sample cuvette while an equal volume of vehicle solvent was added to the reference cuvette. Care was taken that the final concentration of added solvent in each cuvette did not exceed 1.5%. Difference spectra were acquired after a 1-min equilibration time. All spectra were recorded at 22 °C (room temperature). Data were imported into the Origin v.7.5 software package (OriginLab Corp., Northampton, MA) for analysis. The absolute change in absorbance between the peak versus the trough was plotted as a function of ligand concentration. To obtain an accurate binding affinity constant, the data were fit to a single site binding model using the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten equation.

1H,13C-HSQC NMR Measurements

1H,13C-HSQC spectra were acquired on a Varian Inova 600-MHz spectrometer equipped with a 1H/13C/15N triple resonance ColdprobeTM with actively shielded pulse-field gradients at 298 K. Spectra were acquired with 40 scans using spectral widths of 8385 Hz (1H) and 1600 Hz (13C), 128 complex points in one dimension, and a 1-s recycle time. Each NMR sample consisted of 250 μl of a 0.35 mm concentrated solution of labeled CYP119-[13C]MeOF protein in a 100 mm potassium Pi, pH 7.4, buffer with 10% D2O added as a lock solvent placed in a Shigemi tube. For the ligand titration experiments, aliquots of a concentrated stock solution were added sequentially to reach the desired final concentrations for each experiment, and then data were recorded using the above conditions. Data processing and analysis were performed in the program NMRPipe (31) using a two-dimensional Rance-Kay acquisition mode.

Molecular Dynamics

The starting structure for the molecular dynamics simulation was the 2.05-Å CYP119 structure from the archeon Sulfolobus acidocaldarius (PDB ID 1IO9) (32). The missing residues at the C terminus were added using PyMOL.3 Molecular dynamics was performed using the Gromacs software package (33) and the OPLS force field (34) in explicit TIP3P water (35). The water box was 15 Å from the protein on all sides (i.e. the starting structure had 30 Å between periodic images). The simulations were periodic boundary simulations run at 300 K with 4-fs timestep increments. The NVT ensemble was maintained with Berendsen temperature coupling (36) with a relaxation time of 1 ps. Hydrogen bonds were constrained using the LINCS algorithm (37). Seven Na+ ions were added to maintain a neutral charge. Long range electrostatic interactions were treated by using the particle-mesh Ewald method (38). Previously published heme atom parameters such as partial charges were used (39), with the heme Fe3+ coordinated to O2. In its entirety, the simulation contained 77,588 atoms, including: 6,664 atoms in the protein, 23,639 waters, and 7 Na+ ions. Energy minimization was followed by a 200-ps equilibration with Berendsen pressure coupling (36). Data are based on one 200-ns trajectory, which ran on 8 nodes on a Simprota Corp. Linux cluster.

Coarse-grained Modeling

Anisotropic Network Models were built by approximating each residue as a sphere centered at the Cα position. The heme was approximated with five spheres at the following locations: Fe3+ and four carbons at the four outer corners of the planar heme structure (CMA, CMB, CMC, and CMD). Anisotropic Network Models modes were calculated using the Anisotropic Network Models server (40).

RESULTS

Location of Residues in CYP119 Chosen for Mutation

Crystal structures of the ligand-free versus ligand-bound forms of CYP119 clearly demonstrate the importance of conformational flexibility in the F/G loop hinge region to accommodate ligand binding (Fig. 1). Therefore, to examine the impact of conformational dynamics on particular residues within this region, we chose three phenylalanine residues, Phe-144, Phe-153, and Phe-162 (Fig. 1), that undergo dramatically different types of motion upon ligand binding. Additionally, phenylalanine residues were specifically chosen to minimize any distortion in the protein backbone that might be caused by the introduction of the unnatural amino acid residue.

FIGURE 1.

Comparison of crystal structures for the ligand-free (A), imidazole-bound (B), and 4-phenylimidazole-bound (C) CYP119 enzyme.

Expression and Characterization of the CYP119-[13C]MeOF Unnatural Amino Acid Mutants

Unnatural amino acid mutants were expressed and purified to homogeneity as described previously (28). To examine the extent and efficiency of [13C]MeOF incorporation into the protein, whole protein ESI-MS was performed (supplemental Figs. S1 and S2). The deconvoluted spectra corresponded to a mass of 42,897 ± 5 Da, an increase from the wild-type protein of +36 ± 5 Da, demonstrating the incorporation of a single [13C]MeOF residue. To assess the integrity of each mutant protein, UV-visible optical difference spectroscopy was used to monitor the mutant protein's ability to bind the ligands used in this study and hence to induce an optical spin-state shift in the heme Soret bands (supplemental Fig. S3). Optical binding data were plotted and fit to the Michaelis-Menten hyperbolic binding equation to obtain Kd parameters for each ligand (supplemental Table S1). For all ligands examined, the Kd parameters were similar to those obtained for the wild-type enzyme. Finally, to determine the relative thermostability of the [13C]MeOF mutant enzyme compared with the CYP119 wild-type enzyme, the decay of the reduced, CO-bound P450 spectrum was monitored as a function of temperature (29). The measured Tm for the CYP119 wild-type enzyme was 89.6 °C and that for the CYP119-F162[13C]MeOF mutant was 89.9 °C, which indicates that the mutation has essentially no effect on the protein thermostability (supplemental Fig. S4).

1H,13C-HSQC Spectra of Ligand-free CYP119-[13C]MeOF

Surprisingly, initial examination of the 1H,13C-HSQC spectra of all three mutants in the absence of any ligand revealed the presence of two symmetrical resonances of approximately equal intensity, separated by between 0.012 and 0.8 ppm in the 1H dimension (Fig. 2A). This has not been observed in previous studies on other unrelated proteins with the [13C]MeOF unnatural amino acid residue incorporated (41, 42), which suggests that the unique environment of the [13C]MeOF residue(s) in CYP119 leads to splitting of the resonance signal in the 1H dimension. Similar splitting effects have been observed with putidaredoxin in the P450cam system with 15N amide backbone resonances (43). These effects can generally be attributed to the close proximity of the paramagnetic heme iron. Indeed, upon reduction with sodium dithionite and CO binding, the doublet is reduced to a single species (Fig. 2B). The resonances from the [13C]MeOF residues in all three mutants were well separated and confined to a relatively narrow spectral window, from 3.2 to 3.95 ppm in the 1H dimension and from 63 to 65.5 ppm in the 13C dimension (Fig. 2A).

FIGURE 2.

A, 1H,13C-HSQC spectra of the ligand-free CYP119 [13C]MeOF mutants. B, 1H,13C-HSQC spectra of the ligand-free CYP119-F162[13C]MeOF mutant after reduction with dithionite and binding to CO.

Titration of [13C]MeOF Mutants with the Low Affinity Inhibitor Imidazole

Imidazole, a low affinity CYP P450 inhibitor, forms a coordination complex with the heme iron through the lone pair electrons of the nitrogen, generating a low spin Type II spectral complex (10). As can be seen in the crystal structure of CYP119 with imidazole bound, a major conformational rearrangement takes place upon binding of this ligand, with the flexible F/G loop region reorganizing within the active site to accommodate the imidazole ligand (Fig. 1B) (44). Upon titration with imidazole and subsequent 1H,13C-HSQC analysis, new resonance(s) corresponding to the ligand bound form of the enzyme appeared in the spectra of all three mutants (Fig. 3, A–C). Additionally, the split proton resonance seen in the ligand-free form of the enzyme collapsed to a single resonance upon ligand binding. Unexpectedly, even at saturating concentrations of ligand, resonances from the “ligand-free” species are still present in the spectra for the three mutants. Furthermore, the resonance(s) for the imidazole-bound species demonstrates much broader linewidths than that of the ligand-free species, suggesting a greater degree of conformational heterogeneity with the [13C]MeOF residue in the ligand-bound form of the enzyme than in the ligand-free form (Fig. 3, A–C). Imidazole binding to the F144[13C]MeOF mutant induces a more subtle chemical shift than that seen with either the F153[13C]MeOF or the F162[13C]MeOF mutants, with the resonance from the ligand-bound form being located only 0.15 ppm (in the 1H dimension) and 0.5 ppm (in the 13C dimension) from the nearest ligand-free resonance, at 1H = 3.6 ppm and 13C = 63 ppm (Fig. 3A). This is perhaps not surprising given that the major structural rearrangement that takes place upon imidazole binding has only a marginal effect on the Phe-144 residue, resulting in a slight shift of the phenyl side chain from being parallel to the active site heme to being perpendicular (Fig. 1B). The chemical shift of the ligand-bound species in the 13C dimension is also located slightly downfield from the ligand-free resonances, suggesting a more deshielded chemical environment (Fig. 1B). In the case of the F153[13C]MeOF mutant, at low (sub-stoichiometric) concentrations of imidazole, a new, broad resonance corresponding to the ligand-bound species appears at 1H = 2.9 ppm, 13C = 59.2 ppm (Fig. 3B). However, at higher concentrations of imidazole, approaching stoichiometry, a new resonance appears in the spectrum at 1H = 3.7 ppm and 13C = 61.1 ppm (Fig. 3B). As the enzyme is further titrated with imidazole, the initial ligand-bound resonance seen at lower concentrations begins to decrease in favor of the new resonance at 1H = 3.7 ppm, 13C = 61.1 ppm. In contrast, the F162[13C]MeOF mutant only exhibits the appearance of a single new resonance in the presence of the inhibitor imidazole (Fig. 3B) that increases in intensity as a function of the ligand concentration.

FIGURE 3.

1H,13C-HSQC spectra of the ligand-bound CYP119 [13C]MeOF mutants F144[13C]MeOF, F153[13C]MeOF, and F162[13C]MeOF, respectively. For the sake of brevity, only the 1:1 (protein:ligand) stoichiometric concentration is shown. Ligands used are as follows: F144[13C]MeOF with imidazole (A), 4-phenylimidazole (D), and lauric acid (G); F153[13C]MeOF with imidazole (B), 4-phenylimidazole (E), and lauric acid (H); and F162[13C]MeOF with imidazole (C), 4-phenylimidazole (F), and lauric acid (I). Arrows point to ligand-bound resonances.

Titration of [13C]MeOF Mutants with the High Affinity Inhibitor 4-Phenylimidazole

Very different effects were observed on the 1H,13C-HSQC spectrum when each mutant was titrated with the tight binding inhibitor 4-phenylimidazole. In the case of the F144[13C]MeOF mutant, a smaller downfield chemical shift was seen than with either the Phe-153 or the Phe-162 mutants, consistent with the results obtained from the imidazole titration (Fig. 3D). Although the ligand-bound species was again represented by a single resonance, it did not experience the substantial line broadening associated with the binding of imidazole (Fig. 3D). In the case of the F162[13C]MeOF mutant, again the ligand-bound species was represented by the appearance of a single new resonance, at 1H = 3.7 ppm, 13C = 57.3 ppm (Fig. 3F). However, titration of the F153[13C]MeOF mutant with 4-phenylimidazole led initially to the production of a single resonance for the ligand-bound species, at 1H = 3.7 ppm, 13C = 58.2 ppm, then the appearance of a second resonance at higher ligand concentrations (1H = 3.65 ppm, 13C = 62.3 ppm), as also seen with imidazole (Fig. 3E).

Titration of [13C]MeOF Mutants with the High Affinity Substrate Lauric Acid

To understand and compare the conformational changes that take place upon substrate binding, 1H,13C-HSQC titrations were conducted with the substrate lauric acid. In all cases, the resonances split in the 1H dimension were converted into a single resonance in the ligand-bound form (Fig. 3, G–I). Additionally, in all cases, the resonance for the ligand-bound species was shifted downfield from the ligand-free resonances. Surprisingly, the addition of saturating amounts of lauric acid led to complete conversion to the ligand-bound conformer, unlike the titrations with the inhibitors imidazole and 4-phenylimidazole.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Ligand-free CYP119

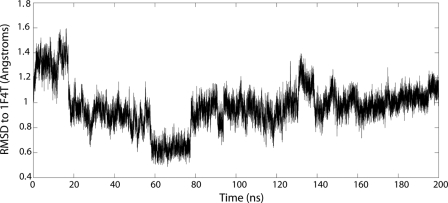

To obtain a more thorough understanding of the conformational subspace available to CYP119, a molecular dynamics simulation was conducted. The simulation began with the ligand-free crystal structure (PDB 1IO9) as the starting point and was allowed to run for 200 ns with 4-fs timestep increments. To the authors' knowledge, this is the longest all-atom molecular dynamics simulation ever conducted for a cytochrome P450 enzyme. In comparison, the molecular timescale for the 1H,13C-HSQC experiments conducted in this study varied on the order of microseconds to milliseconds, therefore some of the motion captured in the simulation may not be reflected in the NMR data. However, it is instructive to be able to understand the dynamic range of conformational subspace available to CYP119. To validate the simulation results, we compared our dynamics data to previously established structural and biochemical models for CYP119 (29, 44). As can be seen in Fig. 4, the greatest degree of motion (as defined by the relative r.m.s.d. from the starting structure), occurs in the F/G loop region, spanning residues Val-151 to Leu-164. However, even within this region there appear to be varying degrees of motion, as can be seen between residues Lys-157 and Glu-160 (Figs. 4, 5B, and 6B). These observations are consistent with crystallographic (32, 45), mutagenesis (29), and previous molecular dynamics (46, 47) studies that confirm the flexible nature of the F/G loop and its role in ligand recognition and catalysis. Because the largest conformational changes both between crystal structures and within our molecular dynamics trajectory occurred in the F/G loop region, we defined individual conformational states by the relative G loop location to avoid diluting out changes in r.m.s.d. by averaging over many residues that do not undergo conformational changes. Surprisingly, at ∼66 ns into the simulation, the ligand-free enzyme adopts a conformation remarkably similar to the 4-phenylimidazole ligand-bound form of the enzyme (Figs. 5 and 7). Thereafter, the structure begins to diverge again and drift away from the ligand-bound form of the enzyme, finally resulting in the structure represented in Fig. 6. Of the three mutated residues in the F/G loop region, the Phe-153 residue is clearly the most mobile, and it spends a significant portion of time sampling a variety of conformations within the active site.

FIGURE 4.

Crystal structure of the ligand-free CYP119 enzyme color-coded to regions of dynamic motion as identified by the 200-ns all-atom molecular dynamics simulation. Blue regions indicate areas with the least amount of fluctuation from the ligand-free starting structure (<1 Å r.m.s.d.), whereas red regions indicate areas with the greatest degree of fluctuation from the ligand-free structure (>5 Å r.m.s.d.).

FIGURE 5.

A, the 66-ns time point from the all-atom molecular dynamics simulation (copper) superimposed upon the 4-phenylimidazole-bound CYP119 crystal structure (blue). B, close-up view of the F/G loop region (residues 151–159) showing the adoption of the ligand-bound conformation at ∼66 ns into the simulation.

FIGURE 6.

A, the 200-ns endpoint of the all-atom molecular dynamics simulation (yellow) superimposed upon the 4-phenylimidazole-bound CYP119 structure (blue). B, close-up view of the F/G loop region (residues 151–159) showing deviation from the ligand-bound conformation.

FIGURE 7.

Plot of the average r.m.s.d. of the F/G loop region (residues 151–159) of the ligand-free form of CYP119 versus the time course of the 200-ns molecular dynamics simulation. Each point corresponds to 2 ns of the 200-ns trajectory.

DISCUSSION

Cytochrome P450 enzymes are remarkable for their ability to recognize a wide variety of chemically diverse substrates (10, 48). This is even more astonishing given that the enzyme superfamily has an extremely conserved fold (10, 49). Ligand binding and recognition form the first, and arguably most important, step in the cytochrome P450 catalytic cycle. Although many studies over the years have focused on this crucial step in the cycle, the question still remains: how does just one enzyme recognize, and effect catalysis, over such a wide variety of chemically diverse substrate species (17, 50, 51)? An increasing amount of evidence from both NMR and molecular dynamics simulations suggests that intrinsic protein dynamics play an important role in ligand binding and catalysis for many enzymes, including P450s (1, 3, 7, 18, 52, 53). In addition to the global conformational changes that take place upon ligand binding, local motions within domains may help reposition the substrate for catalytic oxidation, or may aid in the catalytic process itself (4, 54). Therefore, it is important to examine conformational changes that occur on the sub-domain level, or even on the scale of individual residues, to have a comprehensive understanding of how molecular motion contributes to enzyme functionality (55). In particular, inspection of specific residues that interact directly with the ligand during the course of binding may give us insight as to whether induced fit or conformational selection mechanisms predominate. Here, we have examined both inhibitor and substrate binding in the F/G loop region of the thermophilic cytochrome P450 CYP119 by using a high resolution, site-specific two-dimensional NMR technique in conjunction with all-atom molecular dynamics simulations. Ligand binding titrations were carried out for each mutant using a low affinity inhibitor (imidazole), a high affinity inhibitor (4-phenylimidazole), and a high affinity substrate (lauric acid). Ligand-induced conformational changes were analyzed by conducting 1H,13C-HSQC two-dimensional NMR experiments for each condition examined. Both inhibitor and substrate binding events were readily observable as unique, distinct resonances in the 1H,13C-HSQC spectrum, confirming the utility of this technique as a method for independently monitoring ligand binding to cytochrome P450s. Additionally, a 200-ns molecular dynamics simulation provided independent evidence of inherent structural flexibility in the F/G loop ligand recognition region and demonstrated conformational changes consistent with those seen in the ligand-bound (Fig. 1C) crystal structure. The results further indicate that conformational selection may play an important role in ligand binding.

1H,13C-HSQC Spectra of Ligand-free CYP119-[13C]MeOF Unnatural Amino Acid Mutants

The cross-peaks representing the ligand-free species for all three mutants examined in this study are clustered in a relatively narrow spectral window (Fig. 2A). This has been observed previously with other unrelated proteins containing the [13C]MeOF residue and may be indicative of the intrinsic properties of the 13C-[13C]MeOF spin system (28, 41). More surprisingly, the resonance signal from the labeled [13C]MeOF residue in each mutant is split into a doublet in the 1H dimension (Fig. 2A). However, upon reduction with dithionite and binding to CO, the doublet coalesces into a single resonance (Fig. 2B), suggesting that the doublet seen with the ferric form of the enzyme is primarily due to the close proximity of the paramagnetic heme iron. Finally, the resonance signals from the individual mutants are clearly distinguishable and non-overlapping, suggesting a well folded and homogenous protein, as confirmed by optical ligand binding studies (supplemental Fig. S3).

Titration of CYP119-[13C]MeOF Mutants with the Inhibitors Imidazole and 4-Phenylimidazole

Titration with the low affinity inhibitor imidazole resulted in a new, ligand-bound resonance (Fig. 3, A–C) that exhibited significant line broadening compared with either the ligand-free resonances or the ligand-bound resonances for 4-phenylimidazole and lauric acid (Fig. 3, D–F and G–I, respectively). This suggests greater conformational exchange in the imidazole-bound species than when 4-phenylimidazole or lauric acid is bound. The Kd for imidazole binding to CYP119 was ∼1000-fold weaker than that for 4-phenylimidazole (∼140 μm versus <200 nm, supplemental Table S1). In addition, imidazole is much more water-soluble than 4-phenylimidazole. Its small size and hydrophilic nature give it easy access to the CYP119 active site. However, once there, it may not compete as effectively as the bulkier, more hydrophobic ligands 4-phenylimidazole and lauric acid for displacement of the axial H2O ligand. As a result, imidazole binding led to a less rigidly structured active site, with a lower degree of hydrophobic packing between residues and ligand, as can be seen from the crystal structure of the ligand-bound form (Fig. 1B). Local motion of the ligand that occurs within the active site, e.g. upon binding and dissociation of the imidazole nitrogen from the heme iron, promotes a higher degree of conformational mobility of the F/G loop Phe residues. This higher degree of conformational mobility is reflected in the substantial line broadening seen in the resonance signals from the imidazole-bound form of the enzyme (Fig. 3, A–C). Interestingly, during titrations with both the imidazole and 4-phenylimidazole inhibitors, the F153[13C]MeOF mutant exhibited a single new resonance at low (sub-stoichiometric) ligand concentrations. However, at higher ligand concentrations, this resonance begins to decrease in intensity in favor of a new resonance that appears in the spectrum. This suggests the presence of a stable conformational intermediate that appears only at low ligand occupancy of the enzyme. In comparison, the F162[13C]MeOF and F144[13C]MeOF residues appear to be insensitive to this conformational intermediate. The fact that only the F153[13C]MeOF residue seems to be sensitive to this intermediate underscores the importance of the placement of the [13C]MeOF probe to obtain complete information on the conformational dynamics of a particular protein. This is a critical factor to be noted in the design of future experiments. In a recent crystallographic and pre-steady-state kinetic analysis of ligand binding to cytochrome P450 EryK, it was demonstrated that, after an initial conformational selection step takes place, an additional reorientation of active site residues occurs, effectively “locking” the enzyme into one conformation (18). Additionally, biphasic ligand binding kinetics have been observed in mammalian P450s, suggesting the formation of an initial “encounter” complex that then leads to secondary conformational changes that transition the ligand into a productive binding orientation within the active site (15). This phenomenon appears to be represented in the F153[13C]MeOF mutant by the appearance of a transient resonance peak corresponding to an intermediate species between the ligand-free form of the enzyme (Fig. 1A) and the 4-phenylimidazole- or imidazole-bound form (Fig. 1, B and C). Furthermore, studies of ligand binding to P450cam have shown that ligands can undergo reorientation within the active site after initial binding, leading to production of a conformationally distinct species (56, 57). A recent two-dimensional NMR study examining camphor binding to P450cam identified a peripheral binding site for the ligand, suggesting that an initial binding event occurs at this site before ligand migration into the active site (58). An alternative, albeit less likely, interpretation of the data is that, at low ligand concentrations, the initial ligand-bound resonance that appears represents a singly occupied species, whereas the second resonance that appears later in the titration represents a doubly occupied species. Although allosteric cooperativity is a common phenomenon in cytochrome P450 enzymes, there is no evidence that this occurs in CYP119. Additionally, UV-visible optical difference binding isotherms are best fit to the hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten binding equation, indicative of a single ligand binding event (supplemental Fig. S3).

Compared with the line broadening seen with the imidazole ligand, binding of 4-phenylimidazole leads to the production of a single sharp resonance representing the ligand-bound species in the case of the Phe-144 and Phe-162 mutants, or again two resonances in the case of the Phe-153 mutant, indicating the presence of specific ligand-bound conformers in solution (Fig. 3, D–F). In the titration of the F144[13C]MeOF mutant, a relatively small chemical shift for the ligand-bound species (∼0.9 ppm in the 13C dimension) was observed. The Phe-144 residue undergoes a similarly small conformational adjustment, i.e. a slight shift of the phenyl side chain from being parallel to the active site heme to being perpendicular, upon both imidazole and 4-phenylimidazole binding (Fig. 1, B and C). A much more dramatic chemical shift is seen with the F162[13C]MeOF mutant, wherein the ligand-bound species is shifted ∼7.7 ppm in the 13C dimension and ∼0.1 ppm in the 1H dimension. This is consistent with the >6-Å r.m.s.d. shift of the Phe-162 residue seen in the crystal structure from the ligand-free form to the ligand-bound form (Fig. 1, A and C).

Unexpectedly, even at saturating ligand concentrations, resonances from the ligand-free species are still present in the spectra of the three mutants with both the imidazole and 4-phenylimidazole ligands. One intriguing explanation for this is the possibility that the ligand-free state of the enzyme, represented by the crystal structure, may still be accessible in the “ligand-bound” state of the enzyme (28).

Titration of CYP119-[13C]MeOF Mutants with the Substrate Lauric Acid

In contrast, when the mutants were titrated with the substrate lauric acid, a direct conversion from the ligand-free form to the ligand-bound form occurred for all three mutants, represented by a single resonance peak in the 1H,13C-HSQC spectrum (Fig. 3, G–I). This suggests that lauric acid binds rather rigidly in the active site, inducing conversion into a single active conformer with no conformational intermediate appearing on the pathway to the ligand-bound ground state. High affinity hydrophobic substrates, such as lauric acid, efficiently displace water from the sixth axial ligand position, thereby converting the heme iron from low to high spin and increasing its reduction potential (10). This, in turn, results in more efficient oxidation of the substrate, compared with weak binding substrates, such as styrene, which have more difficulty in displacing the water and dehydrating the active site (29).

Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Ligand-free CYP119

Molecular dynamics simulations have proven useful for elucidating substrate access and egress channels in cytochrome P450 enzymes (59, 60), predicting ligand binding and recognition (51, 61, 62), and examining the details of the P450 catalytic cycle (63, 64). Here, we were interested in accessing the conformational subspace available to the enzyme to address the question of whether the predominant mode of ligand binding proceeds through conformational selection or induced fit. To accomplish this, the simulation had to be sufficiently long enough to encompass the normal modes of enzyme flexibility as represented by the various crystal structures. Therefore, we extended our simulation to 200 ns. Initial course-grain simulations demonstrated hinge motion in the F/G loop domain, consistent with previous reports (data not shown (7, 47)). Our 200-ns molecular dynamics trajectory provided computational evidence that the ligand-free enzyme samples multiple conformations on the nanosecond timescale, including conformations representative of a ligand-bound state (Fig. 5). At 66 ns, or about one-third of the way into the simulation, the enzyme adopts a conformation remarkably similar to the 4-phenylimidazole ligand-bound form of the enzyme (as defined by r.m.s.d. to the F/G loop conformation in the ligand-bound state 1F4T (Fig. 5)). The enzyme remains in this state for ∼20 ns, and thereafter diverges (Figs. 6 and 7). Thus, the ligand-bound state is short-lived relative to other conformations but, nonetheless, accessible on the timescale sampled. The data suggest that conformational selection may play a major role in ligand binding in cytochrome P450 enzymes, as has been suggested recently (18). In regards to the specific residues examined by the two-dimensional 1H,13C-HSQC NMR studies, qualitatively the Phe-153 residue exhibited a wider range of motion than either the Phe-144 or Phe-162 residues, consistent with its proximity to the active site heme.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated the utility of a novel system for site-specifically introducing a 13C-labeled unnatural amino acid to probe ligand binding dynamics in cytochrome P450 enzymes. In conjunction with all-atom molecular dynamics simulations, it can be a powerful tool for elucidating the types of conformational changes that take place in cytochrome P450 enzymes upon ligand binding and, furthermore, may be especially useful for explaining the role that conformational dynamics plays in the complex enzymatic phenomena exhibited by mammalian P450s.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM25515.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4 and Table S1.

W. L. DeLano (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA.

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- MeOF

- p-methoxyphenylalanine

- s

- singlet

- d

- doublet

- wt

- wild type

- LC

- liquid chromatography

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation

- ESI

- electrospray ionization.

REFERENCES

- 1.Henzler-Wildman K. A., Lei M., Thai V., Kerns S. J., Karplus M., Kern D. (2007) Nature 450, 913–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenmesser E. Z., Millet O., Labeikovsky W., Korzhnev D. M., Wolf-Watz M., Bosco D. A., Skalicky J. J., Kay L. E., Kern D. (2005) Nature 438, 117–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tokuriki N., Tawfik D. S. (2009) Science 324, 203–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benkovic S. J., Hammes-Schiffer S. (2003) Science 301, 1196–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fersht A. (1999) Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science: A Guide to Enzyme Catalysis and Protein Folding, 2nd. Ed., pp. 54–84, W.H. Freeman and Co., New York [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koley A. P., Buters J. T., Robinson R. C., Markowitz A., Friedman F. K. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 5014–5018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hays A. M., Dunn A. R., Chiu R., Gray H. B., Stout C. D., Goodin D. B. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 344, 455–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Muralidhara B. K., Negi S., Chin C. C., Braun W., Halpert J. R. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8051–8061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekroos M., Sjögren T. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 13682–13687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ortiz de Montellano P. R. (2005) Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry, 3rd Ed., pp. 1–34, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams P. A., Cosme J., Ward A., Angove H. C., Matak Vinkoviæ D., Jhoti H. (2003) Nature 424, 464–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yano J. K., Wester M. R., Schoch G. A., Griffin K. J., Stout C. D., Johnson E. F. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38091–38094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yano J. K., Hsu M. H., Griffin K. J., Stout C. D., Johnson E. F. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 822–823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams P. A., Cosme J., Vinkovic D. M., Ward A., Angove H. C., Day P. J., Vonrhein C., Tickle I. J., Jhoti H. (2004) Science 305, 683–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Isin E. M., Guengerich F. P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9127–9136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isin E. M., Guengerich F. P. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 6863–6874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davydov D. R., Halpert J. R. (2008) Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 4, 1523–1535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Savino C., Montemiglio L. C., Sciara G., Miele A. E., Kendrew S. G., Jemth P., Gianni S., Vallone B. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 29170–29179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkins W. M., Wang R. W., Lu A. Y. (2001) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 14, 338–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.James L. C., Tawfik D. S. (2003) Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wester M. R., Johnson E. F., Marques-Soares C., Dijols S., Dansette P. M., Mansuy D., Stout C. D. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 9335–9345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cupp-Vickery J., Anderson R., Hatziris Z. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 3050–3055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ravindranathan K. P., Gallicchio E., Friesner R. A., McDermott A. E., Levy R. M. (2006) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 5786–5791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosshard H. R. (2001) News Physiol. Sci. 16, 171–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma B., Shatsky M., Wolfson H. J., Nussinov R. (2002) Protein Sci. 11, 184–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mittermaier A., Kay L. E. (2006) Science 312, 224–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hansen D. F., Vallurupalli P., Kay L. E. (2008) J. Biomol. NMR 41, 113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lampe J. N., Floor S. N., Gross J. D., Nishida C. R., Jiang Y., Trnka M. J., Ortiz de Montellano P. R. (2008) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 16168–16169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koo L. S., Tschirret-Guth R. A., Straub W. E., Moënne-Loccoz P., Loehr T. M., Ortiz de Montellano P. R. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 14112–14123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu C. C., Schultz P. G. (2006) Nat. Biotechnol. 24, 1436–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park S. Y., Yamane K., Adachi S., Shiro Y., Weiss K. E., Maves S. A., Sligar S. G. (2002) J. Inorg. Biochem. 91, 491–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Der Spoel D., Lindahl E., Hess B., Groenhof G., Mark A. E., Berendsen H. J. (2005) J. Comput. Chem. 26, 1701–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jorgensen W. L., Tirado-Rives J. (1988) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 110, 1657–1666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jorgensen W. L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J. D., Impey R. W., Klein M. L. (1983) J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berendsen H. J., Postma J. P., van Gunsteren W. F., DiNola A., Haak J. R. (1984) J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3684–3690 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hess B., Bekker H., Berendsen H., Fraaije J. (1997) J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1463–1472 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. (1993) J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gogonea V., Shy J. M., 2nd, Biswas P. K. (2006) J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 22861–22871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eyal E., Yang L. W., Bahar I. (2006) Bioinformatics 22, 2619–2627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cellitti S. E., Jones D. H., Lagpacan L., Hao X., Zhang Q., Hu H., Brittain S. M., Brinker A., Caldwell J., Bursulaya B., Spraggon G., Brock A., Ryu Y., Uno T., Schultz P. G., Geierstanger B. H. (2008) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 9268–9281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones D. H., Cellitti S. E., Hao X., Zhang Q., Jahnz M., Summerer D., Schultz P. G., Uno T., Geierstanger B. H. (2010) J. Biomol. NMR 46, 89–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pochapsky T. C., Kostic M., Jain N., Pejchal R. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 5602–5614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nishida C. R., Ortiz de Montellano P. R. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338, 437–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yano J. K., Blasco F., Li H., Schmid R. D., Henne A., Poulos T. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 608–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fishelovitch D., Hazan C., Shaik S., Wolfson H. J., Nussinov R. (2007) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 1602–1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arnold G. E., Ornstein R. L. (1997) Biophys. J. 73, 1147–1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamb D. C., Waterman M. R., Kelly S. L., Guengerich F. P. (2007) Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 18, 504–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mestres J. (2005) Proteins 58, 596–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Isin E. M., Guengerich F. P. (2008) Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 392, 1019–1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wade R. C., Motiejunas D., Schleinkofer K., Sudarko Winn P. J., Banerjee A., Kariakin A., Jung C. (2005) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1754, 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bakan A., Bahar I. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 14349–14354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pochapsky S. S., Dang M., OuYang B., Simorellis A. K., Pochapsky T. C. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 4254–4261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ringe D., Petsko G. A. (2008) Science 320, 1428–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boehr D. D., Nussinov R., Wright P. E. (2009) Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 789–796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Strickler M., Goldstein B. M., Maxfield K., Shireman L., Kim G., Matteson D. S., Jones J. P. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 11943–11950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Asciutto E. K., Madura J. D., Pochapsky S. S., OuYang B., Pochapsky T. C. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 388, 801–814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yao H., McCullough C. R., Costache A. D., Pullela P. K., Sem D. S. (2007) Proteins 69, 125–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cojocaru V., Winn P. J., Wade R. C. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1770, 390–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schleinkofer K., Sudarko Winn P. J., Lüdemann S. K., Wade R. C. (2005) EMBO Rep. 6, 584–589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang H., Kenaan C., Hamdane D., Hoa G. H., Hollenberg P. F. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 25678–25686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Karkola S., Wähälä K. (2009) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 301, 235–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Altarsha M., Wang D., Benighaus T., Kumar D., Thiel W. (2009) J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 9577–9588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun H., Moore C., Dansette P. M., Kumar S., Halpert J. R., Yost G. S. (2009) Drug Metab. Dispos. 37, 672–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.