Current strategies for creating enzyme-like catalysts range from rational[1] and computational design[2] to evolutionary searches of large molecular libraries.[3] Sequence-specific polymers are particularly attractive starting points for these efforts because of their ability to adopt three-dimensional structures that preorganize functional groups for catalysis. Although natural enzymes are constructed from α-amino acids, many other backbone structures can give rise to well-defined secondary and tertiary structures. Such non-natural oligomers, often referred to as “foldamers”, have the potential to display properties akin to those of proteins.[4–8]

β-Peptides are interesting in this context because they adopt a variety of stable secondary structures, including helices, sheets and turns,[4, 9] and quarternary helix-bundle assemblies have been generated.[10, 11] Their predictable structures have been exploited to inhibit microbial growth,[12] disrupt protein-protein interactions,[13] and for other applications.[4,5] Here we show that β-peptides presenting arrays of discrete side chain functional groups can also act as effective catalysts.

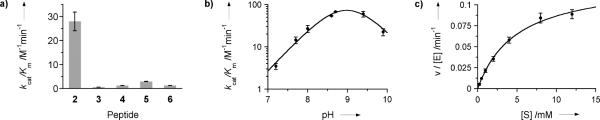

As a model reaction, we examined the retro-aldol cleavage of β-hydroxyketone 1 to give benzaldehyde and pyruvate. This reaction is subject to amine catalysis (Figure 1). The catalytic cycle is initiated by nucleophilic attack of an unprotonated amine on the carbonyl group of the substrate. The resulting iminium ion activates the substrate for C-C bond scission, which occurs with concomitant deprotonation of the hydroxyl group to release benzaldehyde. Tautomerization of the enamine and subsequent hydrolysis produces pyruvate and regenerates the catalyst. This mechanism is exploited by natural type I aldolases,[14] and has been mimicked by lysine-rich amphiphilic α-helical peptides,[15] catalytic antibodies,[16] and most recently by a computationally designed enzyme.[2a]

Figure 1.

Retro-aldol reaction of sodium 4-phenyl-4-hydroxy-2-oxobutyrate (1) and the mechanism of amine catalysis.

Since imine formation is partially limiting in an aqueous environment,[17] the challenge in the design of catalysts for such retro-aldol reactions is to provide a nucleophilic amine under physiological conditions. Studies of enzymes that exploit imine/enamine formation have shown that amine nucleophilicity can be significantly enhanced through Coulombic interactions with nearby cations, which increase the population of the deprotonated state.[18] This strategy, which has been successfully utilized in the design of helical α-peptide catalysts,[15, 17, 19] can be extended to the construction of helical β-peptide catalysts.

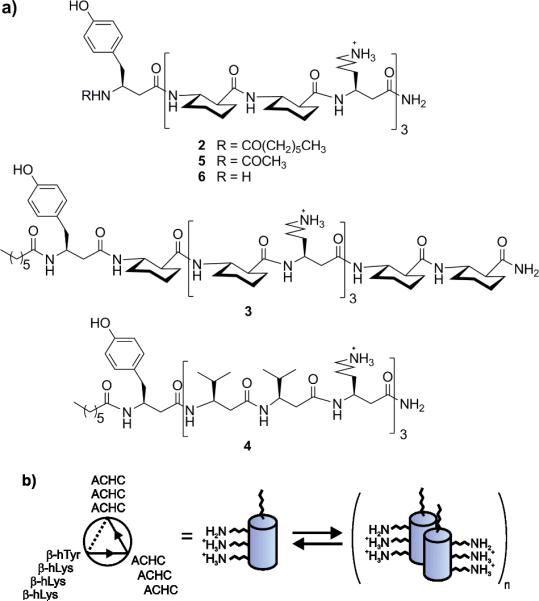

One of the best-understood β-peptide secondary structures is the 14-helix, characterized by 14-membered hydrogen bonds between N-H of residue i and C=O of i+2.[4, 9] This helix is favored by β3-amino acid residues, which bear a side chain on the backbone carbon adjacent to nitrogen. To stabilize such structures in aqueous solution, electrostatic interactions between the side chains[20] or conformationally restricted building blocks[21] can be employed. For example, the cyclically constrained trans-2-aminocyclohexanecarboxylic acid (ACHC), which has a very high helical propensity, has been used to construct short β-peptides that reliably adopt the 14-helical conformation in water, regardless of temperature, pH, or concentration.[21, 22] A β-peptide sequence containing multiple ACHC residues along with β3-homolysine (β3-hLys) residues in an i, i+3, i+6 array should lead to alignment of the amine-containing side chains along one side of a 14-helix (Figure 2). We anticipated that this clustering of β3-hLys residues would cause a decrease in side chain ammonium pKa values and thus facilitate amine catalysis of the retro-aldol reaction of 1.

Figure 2.

a) Sequences of β-peptides 2-6. b) Helical wheel diagram of β-peptide 2 (left) and cartoon showing β-peptide self-assembly (right; the partial protonation state shown is purely hypothetical).

Our design hypothesis was tested with β-peptides 2–4 (Figure 2). β-Peptide 2 has three ACHC-ACHC-β3-hLys triad repeats, a β3-hTyr residue to facilitate concentration determination, and an N-terminus that is capped with a heptanoyl moiety to promote self-assembly.[23] Isomeric β-peptide 3 has a scrambled sequence that does not match the three-residue repeat of the 14-helix; the three β3-hLys residues of 3 should therefore be dispersed around the 14-helix periphery rather than held in close alignment, as in 2. Comparing the activities of 2 and 3 allows us to determine whether the spatial arrangement of the β3-hLys residues is important for catalysis. β-Peptide 4 is an analogue of 2 in which all of the preorganized ACHC residues are replaced by flexible β3-hVal residues. Comparing the activities of 4 and 2 allows us to assess the importance of helical folding for catalysis.

Circular dichroism (CD) measurements provided preliminary insight on the folding and self-assembly of β-peptides 2–4; although CD is an intrinsically low-resolution method, previous correlations with 2D NMR spectroscopy and analytical ultracentrifugation (AU) data provide a basis for interpretation.[22] CD data indicate that 2 is highly 14-helical and self-assembled in aqueous buffer, that 3 is comparably folded but not self-assembled,[22] and that 4 is largely unfolded (Figure S1). The dramatic conformational difference between 2 and 3, which contain ACHC residues, and 4, which lacks ACHC, highlights the strong 14-helix stabilization provided by preorganization at the residue level. Further characterization by NMR (2–4) and AU (2) supports the conclusion that 2 forms large assemblies, while 3 and 4 undergo relatively little self-association (Figure S2). The observation that 2 avidly self-associates while 3 and 4 do not indicates that the heptanoyl unit, alone, is insufficient to induce self-association. Instead, there appears to be a cooperative effect from pairing this terminal unit with a β-peptide segment that forms a stable helical conformation and displays a large, uninterrupted hydrophobic surface. Comparable cooperative effects have been observed among terminally modified α-peptides.[23]

The β-peptides were tested for their ability to promote the retroaldol cleavage of 1, an anionic substrate that is expected to bind well to the cationic catalysts. The reaction was monitored by a standard coupled assay in which lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was used to catalyze the reduction of pyruvate (a retro-aldol product) by NADH. β-Peptide 2 promotes the retro-aldol cleavage of 1 with multiple turnovers (Figure S3) and significant rate accelerations over the uncatalyzed reaction. In contrast, β-peptides 3 and 4 are relatively poor catalysts under identical conditions (Figure 3a). The 20- to 50-fold lower activity for these control β-peptides shows that the activity of 2 requires both a well-folded helix and a properly arrayed set of β3-hLys side chains.

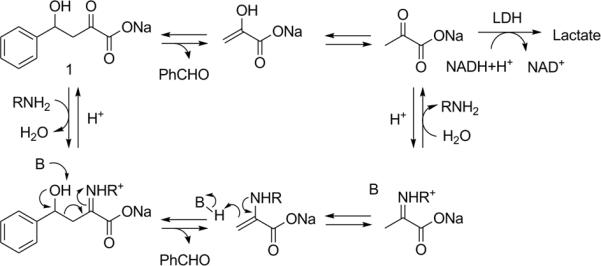

Figure 3.

Kinetic characterization of β-peptide aldolases. Retro-aldol reactions were performed in quartz cuvettes with 50 μM β-peptide, 0.5 mM substrate 1, 0.1 mM NADH and 1 U/mL LDH in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8 containing 150 mM NaCl, at 30 °C. Product formation was coupled to the oxidation of NADH through the LDH-catalyzed reduction of pyruvate and monitored spectroscopically at 340 nm (εNADH = 6220 M−1 cm−1). Rates were corrected for background retro-aldol cleavage and elimination reactions. a) Specific activities of β-peptides 2-6. b) pH-rate profile for β-peptide 2. 10 U/mL LDH were added to compensate for the reduced dehydrogenase activity at high pH. The rate profile was fit to the equation kcat/Km = kHA/(1 + 10 pKa1-pH + 10pH-pKa2). c) Michaelis-Menten plot for 2. The dependence of rate on substrate concentration was determined both in continuous and discontinuous assay formats. Reactions were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8 containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 μM β-peptide 2 and 0.2–12 mM substrate at 30 °C. 0.5 mM NADH and 2 U/mL LDH were added for continuous monitoring.

The impact of N-terminal acyl group modification indicates that β-peptide self-assembly is important for generation of the catalytic species. Replacing the heptanoyl group with an acetyl group, to generate β-peptide 5, reduces the characteristic CD signature for self-assembly but not the CD signature for 14-helical secondary structure (Figure S1); the catalytic activity of 5 is lower than that of 2 by an order of magnitude. β-Peptide 6, which lacks the acyl group altogether, is monomeric up to a concentration of approximately 1 mM,[10] and 6 is >20-fold less active than 2. Some α-peptides designed for amine-mediated catalysis benefit from self-assembly,[17] and in these systems the inter-peptide interactions lead to a significant enhancement of α-helical folding. In contrast, the benefit of self-assembly for β-peptide catalysis is unlikely to be caused by an increase in 14-helicity, because ACHC-rich sequences such as those of 2, 3, 5 and 6 afford very high populations of the helical conformation in aqueous solution even when the β-peptides remain monomeric.[21, 22] The favorable effects that arise from the clustering of β-peptide molecules may reflect a reduction in β3-hLys side chain ammonium pKa, as a result of high local positive charge density or an increase in the hydrophobicity of the environment of catalytic amines. Alternatively, an interface between helical β-peptides could act as a primitive substrate-binding pocket. These postulated effects could operate in tandem.

As suggested by the mechanism proposed in Figure 1, the reaction catalyzed by 2 is pH-dependent. A bell shaped pH-rate profile is observed, with a maximum rate at pH 9 and pK1 = 8.8 ± 0.2 and pK2 = 9.2 ± 0.2 (Figure 3b). Although the available data do not allow assignment of the inflections to specific ionizing groups, the lower value is consistent with the participation of a β3-hLys side chain amino group that has an unusually low pKa. The decrease in activity at high pH could indicate bifunctional acid-base catalysis, or reflect a change in the aggregation state of the β-peptide. Additional evidence for the postulated mechanism was obtained by trapping imine intermediates by reduction with NaCNBH3. Masses corresponding to peptides modified with pyruvate product, one or two aldol substrates, and one aldol and one pyruvate group simultaneously were detected by LC-MS (Figure S4).

The efficiency of β-peptide catalysis was evaluated by steadystate kinetic measurements. The retro-aldolase reaction catalyzed by 2 follows Michaelis-Menten behavior (Figure 3c). At pH 8.0 and 30 °C, the steady state parameters kcat and Km are 0.13 ± 0.01 min−1 and 5.0 ± 0.6 mM, respectively. Comparison of the turnover number with the rate constant for the uncatalyzed retro-aldol reaction under identical conditions (Figure S5) gives a rate acceleration of kcat/kuncat = 3,000. Although substantially lower than the rate accelerations achieved by natural enzymes, this value compares favorably with the activity of catalysts designed for the cleavage of 4-hydroxy-4-(6-methoxy-2-naphthyl)-2-butanone, a process related to the retro-aldol reaction of 1. Thus, the simple β-peptide 2 is roughly twice as efficient as evolutionarily optimized α-peptide aldolases (kcat = 5.6 × 10−4 min−1, Km = 1.8 mM, kcat/kuncat = 1,400),[15] and only eightfold less efficient than the best computationally designed aldolases (kcat = 9.6 × 10−3 min−1, Km = 0.5 mM, kcat/kuncat = 24,000).[2a] The small difference in rate enhancement between a 10-residue β-peptide and a 200-residue protein underscores the catalytic potential in β-peptide scaffolds. Furthermore, unlike helices formed by α-peptides, the β-peptide 14-helix is very stable when preorganized ACHC residues are incorporated. In fact, β-peptide 2 retains high aldolase activity even at 80 °C (kcat = 3.5 ± 0.2 min−1, Km = 5.5 ± 1.0 mM, kcat/kuncat = 1,300 (Figures S6 & S7)), dramatically illustrating the robustness of this scaffold.

Although only 10 residues long and designed according to very simple principles, β-peptide 2 displays excellent catalytic properties. Our results suggest that β-peptidic structures may be versatile scaffolds for engineering catalytic activities. Nevertheless, the prototypic β-peptide catalyst presented here is not optimal. The high Km value likely reflects the lack of a defined substrate-binding pocket. Moving from secondary to tertiary structure should allow creation of true active sites in which functional groups can be effectively oriented for highly efficient catalysis. Recent approaches toward higher-order foldamer structures,[8, 11, 24] and the diversity of backbone chemistries available to folding oligomers in general,[5, 6] present exciting opportunities for developing more sophisticated catalysts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Schweizerischer Nationalfonds, NIH grant GM056414 (to S.H.G.), and the Nanoscale Science and Engineering Center at UW-Madison (NSF DMR-042588). We thank Dennis Gillingham for help with substrate preparation.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://www.angewandte.org or from the author.

References

- [1].Breslow R. Artificial Enzymes. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Jiang L, et al. Science. 2008;319:1387–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.1152692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rothlisberger D, et al. Nature. 2008;453:190–195. doi: 10.1038/nature06879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Jäckel C, Kast P, Hilvert D. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2008;37:153–173. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.125832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Miller SJ. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:601–610. doi: 10.1021/ar030061c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Seebach D, Beck AK, Bierbaum DJ. Chem. Biodiv. 2004;1:1111–1239. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200490087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Goodman CM, Choi S, Shandler S, DeGrado WF. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:252–262. doi: 10.1038/nchembio876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hecht S, Huc I. Foldamers: Structure, Properties, and Applications. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [7].See for example: Smaldone RA, Moore JS. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:2650–2657. doi: 10.1002/chem.200701503.; Yi HP, Wu J, Ding KL, Jiang XK, Li ZT. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:870–877. doi: 10.1021/jo0619940.

- [8].Lee B-C, Chu TK, Dill KA, Zuckermann RN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8847–8855. doi: 10.1021/ja802125x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Cheng RP, Gellman SH, DeGrado WF. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:3219–3232. doi: 10.1021/cr000045i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Raguse TL, Lai JR, LePlae PR, Gellman SH. Org. Lett. 2001;3:3963–3966. doi: 10.1021/ol016868r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Daniels DS, Petersson EJ, Qiu JX, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:1532–1533. doi: 10.1021/ja068678n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].a) Porter EA, Wang X, Lee H-S, Weisblum B, Gellman SH. Nature. 2000;404:565–565. doi: 10.1038/35007145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liu D, DeGrado WF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7553–7559. doi: 10.1021/ja0107475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Arvidsson PI, Ryder NS, Weiss HM, Gross G, Kretz O, Woessner R, Seebach D. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:1345–1347. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Werder M, Hauser H, Abele S, Seebach D. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1999;82:1774–1783. [Google Scholar]; b) Kritzer JA, Luedtke NW, Harker EA, Schepartz A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:14584–14585. doi: 10.1021/ja055050o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) English EP, Chumanov RS, Gellman SH, Compton T. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:2661–2667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Heine A, DeSantis G, Luz JG, Mitchell M, Wong C-H, Wilson IA. Science. 2001;294:369–374. doi: 10.1126/science.1063601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tanaka F, Fuller R, Barbas CF., III Biochemistry. 2005;44:7583–7592. doi: 10.1021/bi050216j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wagner J, Lerner RA, Barbas CF., III Science. 1995;270:1797–1800. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Johnsson K, Allemann RK, Widmer H, Benner SA. Nature. 1993;365:530–532. doi: 10.1038/365530a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Westheimer FH. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Weston CJ, Cureton CH, Calvert MJ, Smart OS, Allemann RK. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:1075–1080. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].a) Cheng RP, DeGrado WF. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5162–5163. doi: 10.1021/ja010438e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Arvidsson PI, Rueping M, Seebach D. Chem. Comm. 2001:649–650. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Raguse TL, Lai JR, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:5592–5593. doi: 10.1021/ja0341485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Pomerantz WC, Grygiel TLR, Lai JR, Gellman SH. Org. Lett. 2008;10:1799–1802. doi: 10.1021/ol800622e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].a) Yu YC, Tirrell M, Fields GB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9979–9987. [Google Scholar]; b) Daugherty DL, Gellman SH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:4325–4333. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Horne WS, Price JL, Gellman SH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:9151–9156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.