Abstract

There has been a steady improvement in cure rates for children with advanced-stage lymphoblastic non-Hodgkin lymphoma. To further improve cure rates while minimizing long-term toxicity, we designed a protocol (NHL13) based on a regimen for childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, which features intensive intrathecal chemotherapy for central-nervous-system-directed therapy and excludes prophylactic cranial irradiation. From 1992 to 2002, 41 patients with advanced-stage lymphoblastic lymphoma were enrolled on the protocol. Thirty patients had stage III and 11 had stage IV disease. Thirty-three cases had a precursor T-cell immunophenotype, 5 were precursor B-cell and in 3 immunophenotype was not determined. Thirty-nine of the 41 (95%) patients achieved a complete remission. The 5-year event-free rate was 82.9% ± 6.3% (SE) and 5-year overall survival rates was 90.2% ± 4.8% (median follow-up 9.3 years [range 4.62 to 13.49 years]). Adverse events included 2 induction failures, 1 death from typhlitis during remission, 3 relapses, and 1 secondary acute myeloid leukemia. The treatment described here produces high cure rates in children with lymphoblastic lymphoma without the use of prophylactic cranial irradiation.

Keywords: advanced-stage, pediatric, lymphoblastic lymphoma

INTRODUCTION

The non-Hodgkin lymphomas of childhood are primarily high-grade tumors as defined by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Working Formulation.(1, 2) They comprise the Burkitt, large-cell, and lymphoblastic subtypes as classified according to the World Health Organization (WHO) system.(2) Lymphoblastic lymphoma represents approximately 30% of all pediatric NHL. The vast majority are advanced stage with a precursor T-cell immunophenotype.

The outcome of treatment for children with NHL has improved over the past 30 years, largely through sequential protocols that used increasingly intensive chemotherapy regimens guided by stage and histology or immunophenotype. (3–10) With modern therapy, at least 75% of children with advanced-stage lymphoblastic lymphoma are long-term, event-free survivors. Most successful treatment strategies for advanced-stage pediatric lymphoblastic lymphoma are derived from regimens designed for children with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). (3, 4, 6, 11) This approach was initially validated by a prospective Children’s Cancer Group trial that compared two of the first successful pediatric NHL regimens, the cyclophosphamide-based COMP regimen and the 10-drug LSA2L2 regimen - the latter designed for the treatment of ALL.(6) Both regimens had an excellent outcome in children with limited-stage disease, regardless of histologic subtype; however, among children with advanced-stage disease, those with Burkitt lymphoma had a better result with the COMP regimen, whereas the LSA2L2 regimen was superior for those with lymphoblastic lymphoma. Subsequent trials for children with lymphoblastic lymphoma attempted to build on these observations with strategies that include intensification of therapy, introduction of new agents(5), and optimization of central nervous system prophylaxis and treatment(3, 11, 12).

Here, we report an analysis of the treatment outcome of 41 children with advanced-stage lymphoblastic lymphoma treated with our institutional ALL-derived regimen, NHL13.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients and treatment

From 1992 to 2002, 41 children were referred to our institution with advanced-stage lymphoblastic lymphoma. By immunophenotyping, the tumor cells were classified as T-lineage in 33 patients and B lineage in 5 patients. In the remaining 3 patients, immunophenotype was not determined. Upon completion of an initial work-up, which included CT imaging of the chest abdomen and pelvis, nuclear imaging with gallium, and examination of the cerebrospinal fluid and bone marrow, patients were classified according to the St. Jude staging system as described by Murphy. (13, 14)

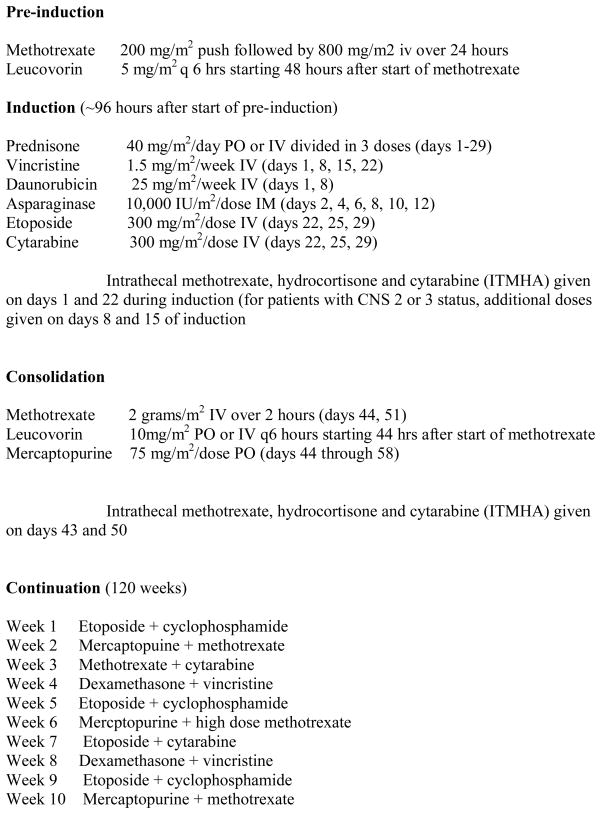

Patients with advanced-stage disease (stage III, n=31 and stage IV, n=10) were eligible for NHL13, an institutional review board approved protocol for children with advanced stage lymphoblastic lymphoma. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents or their legal guardians prior to enrollment. The NHL13 protocol featured remission induction (vincristine, daunomycin, L-asparaginase, prednisone, etoposide, and cytarabine), consolidation (methotrexate at 2 g/m2 and 6-mercaptopurine) and maintenance with weekly rotation of drug pairs (vincristine, dexamethasone, etoposide, cytarabine, cyclophosphamide, low-dose methotrexate, and 6-mercaptopurine), as well as a re-induction (during weeks 16 to 21) and high-dose methotrexate every 8 weeks (for 8 doses) during the first year (Fig. 1). This protocol was based on the Total 13 regimen previously used to treat patients with T-ALL at our institution (15, 16) CNS prophylaxis for patients with CNS-1 status (no blast cells in the CSF) comprised 15 doses of intrathecal methotrexate, hydrocortisone, and cytarabine (IT-MHA)—2 during induction, 2 during consolidation with high-dose methotrexate, and 11 during the first year of continuation therapy (~ every 8 weeks). Patients with CNS-2 status (< 5 WBC/hpf with blast cells in the CSF) or CNS-3 status (≥ 5 WBC/hpf with blast cells in the CSF, or cranial nerve palsy) received 22 doses of IT-MHA, 2 additional doses during induction and 5 additional doses (~ every 4 weeks) during the first year of continuation.

Figure 1.

NHL 13 Treatment Schema which reviews chemotherapeutic agents and dosages for the pre-induction, induction, consolidation and continuation phases. CNS directed therapy is also outlined.

Statistical analysis

The principal end point of the study was event-free survival (EFS), measured from the start of therapy to the date of first treatment failure of any kind (relapse, death or second malignancy) or to the last date of follow-up. Failure to enter remission was considered an event at time zero. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time interval from the start of therapy to death from any cause or to last follow-up. Distributions of EFS and OS were estimated by the method of Kaplan and Meier. The median follow-up is 9.3 years (range, 4.6 to 13.5 years).

RESULTS

The presenting features of patients enrolled in the study are demonstrated in Table 1. The majority of patients were males over 10 years of age with stage III, precursor T-cell disease. Four patients presented with CNS involvement (CNS 3, n=3; CNS 2, n=1).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics at Diagnosis

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at Diagnosis (years) | 2 | 4.9 |

| <3.0 | ||

| >=3.0 | 39 | 95.1 |

| Age at Diagnosis (years) | 17 | 41.5 |

| <10.0 | ||

| >=10.0 | 24 | 58.5 |

| Gender | 27 | 65.9 |

| Male | ||

| Female | 14 | 34.1 |

| Immunophenotype | 5 | 12.2 |

| B | ||

| T | 33 | 80.5 |

| Unknown | 3 | 7.3 |

| Mediastinal Mass | 33 | 80.5 |

| Yes | ||

| No | 8 | 19.5 |

| Bone Involvement | 5 | 12.2 |

| Yes | ||

| No | 36 | 87.8 |

| Marrow Involvement | 7 | 17.1 |

| Yes | ||

| No | 34 | 82.9 |

| Skin Involvement | 2 | 4.9 |

| Yes | ||

| No | 39 | 95.1 |

| Pleura or Pleural effusion | 19 | 46.3 |

| Yes | ||

| No | 22 | 53.7 |

| CNS Involvement | 4 | 9.8 |

| Yes | ||

| No | 37 | 90.2 |

| Murphy Stage | 31 | 75.6 |

| III | ||

| IV | 10 | 24.4 |

| LDH | 30 | 73.2 |

| < 500 U/L | ||

| >=500 U/L | 11 | 26.8 |

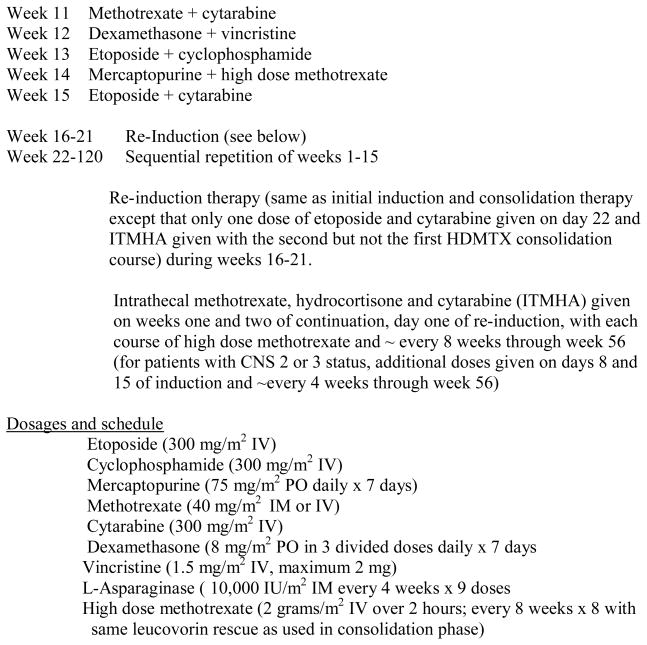

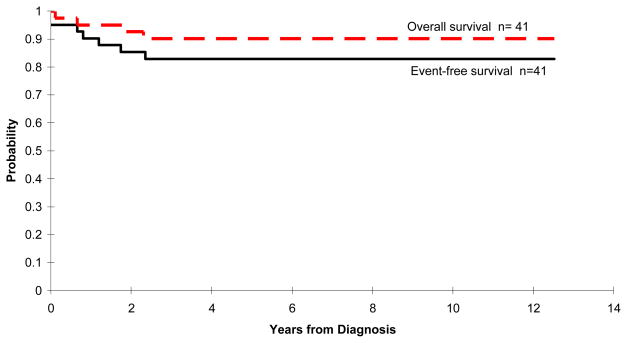

Of the 41 patients enrolled, 39 (95%) achieved a complete remission after the scheduled course of remission induction therapy (39 of 41). Among the two patients who did not achieve a complete remission, one had a residual mediastinal mass at the end of scheduled induction therapy and one died during induction therapy with acute respiratory failure thought to be secondary to an acute thromboembolic event. The 5-year EFS and OS estimates were 82.9% ± 6.3% and 90.2% + 4.8%, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves demonstrating both the event-free and overall survival estimates for the 41 patients enrolled on the trial. The 5-year event-free rate was 82.9% ± 6.3% (SE) and 5-year overall survival rates was 90.2% ± 4.8% (median follow-up 9.3 years [range 4.62 to 13.49 years]).

Adverse events included 3 relapses (2 local and one combined hematological and CNS), 2 induction failures, and death from typhlitis during remission and secondary acute myeloid leukemia (AML) in 1 case each. Two of the 3 children who experienced relapse were successfully salvaged with multi-agent chemotherapy followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). One of the two patients who did not have a complete response entered remission after involved-field irradiation, autologous HSCT, and post-HSCT continuation multi-agent chemotherapy.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study indicate that high cure rates for children with advanced-stage lymphoblastic lymphoma can be achieved with an ALL-based treatment that eliminates prophylactic cranial irradiation. NHL13 resulted in an EFS rate of 83% and a survival rate of 90% with only one non-local relapse among the 39 patients who achieved remission.

The multi-agent nature of the NHL13 protocol makes it difficult to identify the most important determinants of success but the value of high-dose methotrexate is supported by several clinical and laboratory observations. Incorporation of high-dose methotrexate courses in the LMT-81 regimen used by the French Society of Pediatric Oncology reportedly improved cure rates.(4) Likewise, the Berlin-Frankfurt-Munster (BFM) group reported excellent results with its BFM90 regimen, which features a consolidation phase consisting of four courses of high-dose methotrexate (5 g/m2) given every 2 weeks, plus a re-induction phase. (3) The observation that T-cell blasts accumulate methotrexate less avidly than B-lineage blasts and that higher-dose of methotrexate can achieve adequate concentrations of methotrexate polyglutamates in T-cell blasts further supports the value of this approach. (15) Notably, both the POG 9404 (17) study and the recently completed COG A5971 study are randomized to examine the contribution of high-dose methotrexate to treatment outcome.

Additional agents used in NHL13 that are thought to be important in the treatment of advanced-stage lymphoblastic lymphoma include L-asparaginase, anthracyclines, and epipodophyllotoxins. A randomized POG study demonstrated a survival advantage for patients receiving additional L-asparaginase.(5) While anthracyclines are commonly used in successful NHL treatment regimens, (11, 17) the use of epipodophyllotoxins is more controversial. Their use in the POG T3 protocol improved overall outcome but was associated with an increased rate of secondary AML (5). One of 41 patients treated on the NHL13 regimen developed secondary AML, although the 11q23 abnormality typically seen in epipodophyllotoxin-induced secondary AML was not present. Nevertheless, considering the increased rate of secondary AML observed in the T13 regimen from which NHL13 was derived, we recommend that further refinement in therapy for lymphoblastic lymphoma should avoid the use of epipodophyllotoxin compounds for most patients. Another component of the NHL13 regimen that is likely to be important is the re-induction phase, which has been shown to improve outcome in children with ALL. This approach has also been incorporated into other regimens for advanced-stage lymphoblastic lymphoma, including BFM90 (3) and COG A5971.

The need for cranial irradiation in children with lymphoblastic lymphoma has remained controversial. We found that prophylactic cranial irradiation is not required to achieve an excellent treatment outcome. In NHL13, CNS prophylaxis included triple intrathecal therapy with methotrexate, hydrocortisone and cytarabine (15 courses for CNS 1, 22 courses for CNS2) and systemic high-dose methotrexate. Systemic etoposide penetrates the CSF and therefore may be another important component of CNS prophylaxis in this regimen (18). In our study, only one of three patients with recurrent disease had CNS involvement at the time of relapse (combined bone marrow and CNS relapse in a patient who had presented with overt CNS disease). These results are in line with those of the BFM95 study, which did not include prophylactic cranial irradiation and resulted in excellent disease control (12). Together, these results strongly indicate that prophylactic cranial irradiation can be avoided.

Further improvements in treatment outcome for children with lymphoblastic lymphoma may be achieved by identifying those children with a poor early response to therapy. Early response to therapy is the strongest independent predictor of treatment outcome in children with ALL. (19–23) Efforts are currently under way to determine whether this observation holds true for lymphoblastic lymphoma.(24) If so, patients with a very poor early response may be eligible for either novel or intensive salvage therapy with hematopoietic stem cell support.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA 21765), and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

We thank the patients and their families. We thank Sharon Naron for scientific editing.

References

- 1.National Cancer Institute sponsored study of classifications of non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: summary and description of a working formulation for clinical usage. The Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Pathologic Classification Project. Cancer. 1982 May 15;49(10):2112–2135. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820515)49:10<2112::aid-cncr2820491024>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jaffe ES, Harris NL, Stein H, Vardiman JW. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. IARC Press; Lyon: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiter A, Schrappe M, Ludwig WD, Tiemann M, Parwaresch R, Zimmermann M, et al. Intensive ALL-type therapy without local radiotherapy provides a 90% event-free survival for children with T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma: a BFM group report. Blood. 2000;95(2):416–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patte C, Kalifa C, Flamant F, Hartmann O, Brugieres L, Valteau-Couanet D, et al. Results of the LMT81 protocol, a modified LSA2L2 protocol with high dose methotrexate, on 84 children with non-B-cell (lymphoblastic) lymphoma. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1992;20(2):105–113. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950200204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amylon MD, Shuster J, Pullen J, Berard C, Link MP, Wharam M, et al. Intensive high-dose asparaginase consolidation improves survival for pediatric patients with T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and advanced stage lymphoblastic lymphoma: a Pediatric Oncology Group study. Leukemia. 1999 Mar;13(3):335–342. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson JR, Jenkin RD, Wilson JF, Kjeldsberg CR, Sposto R, Chilcote RR, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients treated with COMP or LSA2L2 therapy for childhood non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a report of CCG-551 from the Childrens Cancer Group. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(6):1024–1032. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.6.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tubergen DG, Krailo MD, Meadows AT, Rosenstock J, Kadin M, Morse M, et al. Comparison of treatment regimens for pediatric lymphoblastic non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a Childrens Cancer Group study. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13(6):1368–1376. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.6.1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein HJ, Cassady JR, Levey R. Long-term results of the APO protocol (vincristine, doxorubicin [adriamycin], and prednisone) for treatment of mediastinal lymphoblastic lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 1983;1(9):537–541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1983.1.9.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahl GV, Rivera G, Pui CH, Mirro J, Jr, Ochs J, Kalwinsky DK, et al. A novel treatment of childhood lymphoblastic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: early and intermittent use of teniposide plus cytarabine. Blood. 1985;66(5):1110–1114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandlund JT, Downing JR, Crist WM. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in childhood. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(19):1238–1248. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605093341906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg JM, Silverman LB, Levy DE, Dalton VK, Gelber RD, Lehmann L, et al. Childhood T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute acute lymphoblastic leukemia consortium experience. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Oct 1;21(19):3616–3622. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burkhardt B, Woessmann W, Zimmermann M, Kontny U, Vormoor J, Doerffel W, et al. Impact of cranial radiotherapy on central nervous system prophylaxis in children and adolescents with central nervous system-negative stage III or IV lymphoblastic lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Jan 20;24(3):491–499. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murphy SB. Classification, staging and end results of treatment of childhood non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: dissimilarities from lymphomas in adults. Semin Oncol. 1980;7(3):332–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy SB, Hustu HO. A randomized trial of combined modality therapy of childhood non- Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer. 1980;45(4):630–637. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800215)45:4<630::aid-cncr2820450403>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pui CH, Relling MV, Campana D, Evans WE. Childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Rev Clin Exp Hematol. 2002 Jun;6(2):161–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-0734.2002.00067.x. discussion 200–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pui CH, Boyett JM, Rivera GK, Hancock ML, Sandlund JT, Ribeiro RC, et al. Long-term results of Total Therapy studies 11, 12 and 13A for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia at St Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Leukemia. 2000 Dec;14(12):2286–2294. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Asselin BL, Shuster J, Amylon M, Halperin E, Hutchison R, Lipshultz S, Camitta B. Improved Event-Free Survival (EFS) with High Dose Methotrexate (HDM) in T-Cell Lymphoblastic Leukemia (T-ALL) and Advanced Lymphoblastic Lymphoma (T-NHL): a Pediatric Oncology Group (POG) Study. Proc of ASCO. 2001;20:367. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edick MJ, Gajjar A, Mahmoud HH, van de Poll ME, Harrison PL, Panetta JC, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oral etoposide in children with relapsed or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Apr 1;21(7):1340–1346. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coustan-Smith E, Behm FG, Sanchez J, Boyett JM, Hancock ML, Raimondi SC, et al. Immunological detection of minimal residual disease in children with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 1998 Feb 21;351(9102):550–554. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gaynon PS, Bleyer WA, Steinherz PG, Finklestein JZ, Littman P, Miller DR, et al. Day 7 marrow response and outcome for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia and unfavorable presenting features. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1990;18(4):273–279. doi: 10.1002/mpo.2950180403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gaynon PS, Desai AA, Bostrom BC, Hutchinson RJ, Lange BJ, Nachman JB, et al. Early response to therapy and outcome in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a review. Cancer. 1997 Nov 1;80(9):1717–1726. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971101)80:9<1717::aid-cncr4>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandlund JT, Harrison PL, Rivera G, Behm FG, Head D, Boyett J, et al. Persistence of lymphoblasts in bone marrow on day 15 and days 22 to 25 of remission induction predicts a dismal treatment outcome in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2002 Jul 1;100(1):43–47. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coustan-Smith E, Sancho J, Behm FG, Hancock ML, Razzouk BI, Ribeiro RC, et al. Prognostic importance of measuring early clearance of leukemic cells by flow cytometry in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2002 Jul 1;100(1):52–58. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coustan-Smith EAM, Sandlund JT, Campana D. A Novel Approach for Minimal Residual Disease Detection in Childhood T-Cell Lymphoblastic Lymphoma (T-LL): A Children’s Oncology Group Report. Blood. 2007 November 16;110(11):1042–1043A. [Google Scholar]