Abstract

Objective:

The purpose of this analysis was to examine secular trends in school performance indicators in relationship to the implementation of a program targeting the school food and physical activity environment.

Design:

Data on available school performance indicators were obtained; retrospective analyses were conducted to assess trends in indicators in association with program implementation; each outcome was regressed on year, beginning with the year prior to program implementation.

Setting:

The Healthy Kids, Smart Kids program was a grass-roots effort to enhance the school food and physical activity environment in the Browns Mill Elementary School in Georgia.

Subjects:

Data included publicly available school records from the years 1995 to 2006.

Results:

The number of nurse, counseling, and disciplinary referrals per 100 students demonstrated a downward trend, while standardized test scores demonstrated an upward trend beginning the year of program implementation. School year was a significant predictor of all indicators.

Conclusions:

Promoting nutrition and physical activity within the school environment may be a promising approach for enhancing both student health and educational outcomes.

Keywords: school, nutrition, physical activity, environment

Introduction

Poor dietary intake among U.S. children is well-established (1-3), contributing to a dramatic increase in the prevalence of overweight (4). Childhood overweight contributes to depressed affect, low self-esteem, and social marginalization (5); increases risk for obesity in adulthood (6), and increases risk for adult chronic disease (e.g., 7). Even for non-overweight children, poor diet increases risk for chronic disease (e.g., 8;9). Poor diet and physical inactivity account for an estimated 365,000 deaths per year, second only to tobacco in preventable deaths (10), and result in an estimated $110 to $129 billion annually in direct and indirect health care costs (11).

Because U.S. children consume from 19 to 50% of their daily caloric intake at school (12), the school environment is an important target for improving dietary intake. A body of research clearly indicates that the school food environment impacts children's diet. Vending machines, snack bars, and a la carte programs in schools have been associated with lower consumption of fruits and vegetables, and higher consumption of total fat, saturated fat, and sweetened beverages (13-15).

Multi-component school-based intervention studies involving educational, environmental, and parent components have shown increases in fruit consumption ranging from 0.2-0.6 servings/day and increases in vegetable consumption ranging from 0-0.3 servings/day (16). While the educational components of these studies were generally the primary focus, several have documented positive changes in the nutritional content of school meals (17-19). Only a few studies have specifically examined the effect of modifying the school food environment on children's dietary intake; findings suggest the potential effectiveness of such changes (20-22). Additionally, school policy and procedure changes have resulted in measurable improvements in children's diets and health (23-25).

Despite evidence indicating the importance of the school food environment, findings from the 2007 School Nutrition Dietary Assessment Study indicate that the nutritional composition of school meals is not optimal (26). Less than one-third of public schools served lunches meeting the US Department of Agriculture standards for total or saturated fat. Essentially all meals exceeded the sodium recommendations, and only about 5% of lunch menus contained foods made from whole grains or dried beans. Moreover, less healthy foods that competed with the school lunch foods remained prevalent. Approximately one-third of elementary schools and almost two-thirds of middle and high schools had foods or beverages for sale a la carte during lunch, with candy, desserts, snack foods, soda, and juice drinks the most commonly purchased of these competitive foods.

While data indicate a need for improvement in the school food environment, significant barriers to such change exist. Qualitative research indicates that school personnel perceive that competitive foods are an important source of revenue, that food offerings should include both healthy and unhealthy foods to help students learn to make choices, and that academic achievement is the top priority among many competing demands, such as the healthfulness of foods served (27).

There is an urgent need to determine ways in which the school food environment can be improved in a manner acceptable to school personnel and children and sustainable in terms of cost and effort. Further, evidence is needed to show the effects of changes in the school environment on health and school performance-related outcomes. The purpose of this paper is to describe the development and implementation of the Healthy Kids, Smart Kids program and the trajectory of school performance indicators observed over time prior to and after the implementation of this program. These retrospective analyses do not constitute a formal evaluation of the program; rather, they examine secular trends of publicly available school indicators before and after program implementation.

Methods

Development of the Healthy Kids, Smart Kids program was initiated in the Browns Mill Elementary School in Decatur, Georgia (a suburb of Atlanta) in 1999 in response to the school principal concerns regarding an increase in obesity, high numbers of visits to the school nurse for general complaints, perceived lethargy in many students, and lack of focus and attention in the classroom. Using a community-based, grass-roots approach; the principal formed a nutrition team consisting of the cafeteria manager, three teachers, three parents, the head custodian, a bus driver, two members of student government, two members of the 4H Club, and several neighborhood grocery store managers. The team reviewed the school menus and made recommendations for improvements; changes were made within the existing budgetary constraints of the school's food service program. Additionally, changes were made to the physical education curriculum, and health-oriented topics were integrated into the regular school curriculum across subjects. Parental support for the initiative was facilitated through a series of parent-teacher-student association meetings, workshops, staff developments, and in-services to discuss health and nutrition issues, including education regarding guidelines for food brought to school from home. A key emphasis of the approach was to integrate the program into existing school structures and curricula via an interdisciplinary approach. A summary of the school environment changes implemented is provided as Table 1, and sample menus prior to and after program implementation are provided as Table 2. A program steering committee including representatives from the school council, parent-teacher-student association, student government, and community was formed to guide program development and implementation, and the subsequent school environment changes occurred over approximately one year.

Table 1.

School environment improvements in the Healthy Kids, Smart Kids program

| Food environment |

|

| Physical activity |

|

| Curriculum changes |

|

Based on the 1995 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (32) and Food Guide Pyramid (now replaced by MyPyramid).

Table 2.

Sample school menus prior to and after the implementation of Healthy Kids, Smart Kids program

| Prior to Healthy Kids, Smart Kids |

After Healthy Kids, Smart Kids | |

|---|---|---|

| Monday | Cheese Pizza | Tuna Salad |

| Chicken Nuggets | Veggie Pizza on Whole Grain Crust | |

| Corn | Green Salad | |

| Garden Salad | Carrot & Celery Sticks (Low Fat Ranch Dressing) | |

| Peaches | Fresh Fruit Cup | |

| Cookies | Yogurt | |

| Tuesday | Hamburger | Baked Roasted Chicken |

| Corn Dog | Turkey Sub Sandwich on Whole Grain Bread | |

| Green Beans | Turnip Greens | |

| French Fries | Baked Sweet Potato | |

| Fruit Cocktail | Spinach Salad | |

| graham crackers | Fresh Fruit (Seasonal) | |

| Wednesday | Beef/Cheese Taco | Spaghetti with Turkey Meat Sauce |

| Burrito/Cheese | Grilled Chicken Breast | |

| Tomato/Lettuce | Wheat Rolls | |

| Mixed Vegetables | Mixed Vegetables | |

| Fruit | Green Beans | |

| Banana Pudding | Stewed Pears | |

| Fresh Fruit | ||

| Thursday | Chicken Rings | Turkey Pot Pie |

| Breaded Steak | Meat Loaf | |

| Buttered Rice | Baked White Potato | |

| Garden Salad | Broccoli | |

| Cookie Bar | Garden Salad | |

| Fruit | Fresh Fruit (Seasonal) | |

| Apple Sauce | ||

| Friday | Hot Dog | Chef Salad (Salad Mix with Spinach, Tomatoes, Bell Peppers, Cucumbers, Garbanzo Beans, Turkey and Turkey Ham, Low Fat Cheddar Cheese) |

| Burritos | Loaded Baked Potato (Turkey Chili, Broccoli, Low Fat Cheddar Cheese, Low Fat Sour Cream) | |

| Coleslaw | Whole Grain Roll | |

| French Fries | Fresh Fruit | |

| Cherry Crisp | Italian Organic Ice | |

| Items available all days |

Whole Milk | Low Fat Milk (1% and 2%) |

| Chocolate Milk | Skim Milk | |

| sweetened juice drink | Soy Milk | |

| Ice Cream (cups, bars) | Bottled water | |

| Popsicles | 100% Juice (apple/fruit blend) |

While the Healthy Kids, Smart Kids program was not implemented as part of a research study, publicly available school records were used to examine trends in school indicators relative to the timing of the program implementation, which began in 1999. School indicator data available prior to program development included the Iowa Test of Basic Skills (ITBS) and data on the number of disciplinary referrals. The ITBS is a nationally standardized, norm-referenced test for students from first through eighth grade, designed to assess performance in relation to the national population. Beginning the year prior to program implementation (1998), data on the number of nurse and counseling referrals were also kept. Trends in these indicators in association with implementation of the Healthy Kids, Smart Kids program were examined using regression analyses. Each outcome was regressed on year, beginning the year prior to program implementation through 2006. (ITBS data were only used through 2005, as the standardized testing format was changed in 2006, precluding comparison with previous years.) Data analyses were conducted using SPSS version 13.0.

Results

A summary of the school demographic characteristics across the years analyzed is provided in Table 3. The school primarily served African-American students. Approximately one-third to one-half of the students were eligible for free or reduced lunches through the National School Lunch Program.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of students in Browns Mills Elementary School

| Year | Number of Students Enrolled in School |

% Eligible for the National School Lunch Program |

% African-American |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 1005 | 34.9 | 87.8 |

| 1996 | 1026 | 37.9 | 87.6 |

| 1997 | 834 | 36.9 | 92.0 |

| 1998 | 779 | 50.0 | 93.3 |

| 1999 | 875 | 41.4 | 95.1 |

| 2000 | 945 | 43.7 | 95.4 |

| 2001 | 950 | 43.2 | 95.6 |

| 2002 | 1049 | 51.2 | 96.0 |

| 2003 | 945 | 49.0 | 97.0 |

| 2004 | 1002 | 53.0 | 96.0 |

| 2005 | 1002 | 54.0 | 96.0 |

| 2006 | 1050 | 55.0 | 96.0 |

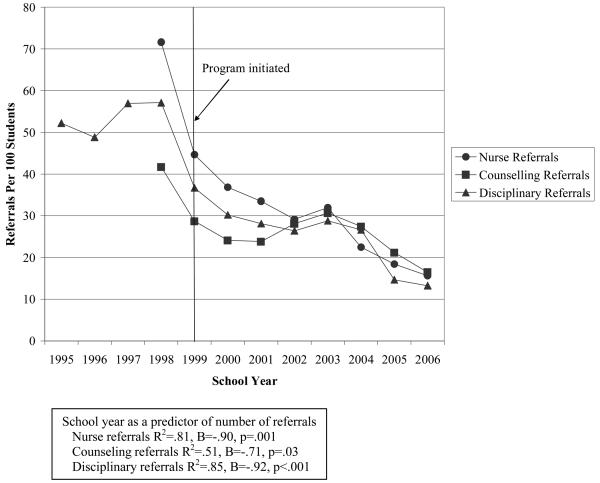

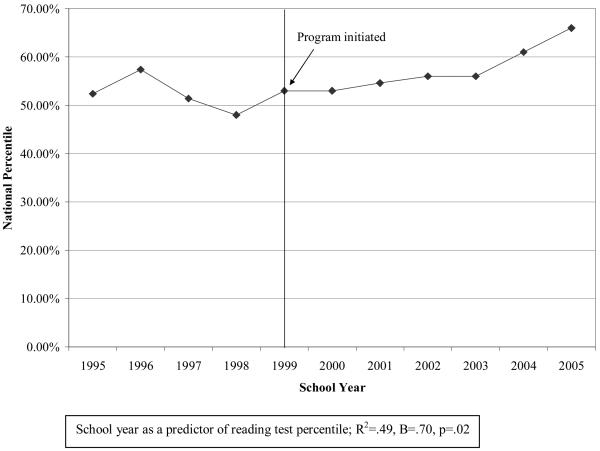

The number of nurse, counseling, and disciplinary referrals per 100 students demonstrated a downward trend beginning the year of program implementation (Figure 1). A slight increase was then observed in all indicators in 2003, followed by a continued decrease. School year was a significant predictor of number of referrals (nurse referrals r2=.81, p=.001; counseling referrals r2=.51, p=.03; disciplinary referrals r2=.85, p<.001). Conversely, standardized test scores demonstrated an upward trend beginning the year of program implementation (Figure 2), and school year significantly predicted test scores (r2=.49, p=.02).

Figure 1.

Number of nurse, counseling, and disciplinary referrals by school year

Figure 2.

Standardized reading test scores by school year

Discussion

Findings from this retrospective analysis suggest that promoting nutrition and physical activity within the school environment may be complimentary to educational needs. Previous research has demonstrated the relationship of undernourishment to cognition and behavior (e.g., 28;29); however, little research has addressed the relationship of dietary quality with these factors. A notable exception is a recent epidemiological study in Nova Scotia, which found that greater overall dietary quality was associated with better performance on a standardized reading assessment after adjusting for weight status, parent/family characteristics, and neighborhood demographic factors (30).

While this analysis was not designed to formally evaluate the program, and improvements in school indicators cannot be causally attributed, secular trends in school indicators associated with program implementation suggest it may be a promising approach for promoting both health and educational outcomes. The success of the program in achieving food and physical activity changes in the school environment suggests the potential effectiveness of a grass-roots approach. Such change must overcome a number of barriers, including changes in the way food is purchased, prepared, and served; acceptability of the new menus by students; competing priorities of school personnel; prioritizing time for physical activity during the school day; and social attitudes normalizing unhealthy foods. As a result, achieving successful environmental change requires a strong champion and achieving buy-in from diverse stakeholders. In this case, the success of the project was facilitated by a highly motivated principal with strong leadership skills who was willing to share her own personal story of wellness as an initial step toward gaining trust and interest from staff, students, and parents. Members of the transdisciplinary team, who demonstrated substantial commitment to the recommended changes, were empowered to make the decisions needed to ensure the success of the program. For example, the cafeteria manager communicated with vendors to obtain healthful foods, developed cafeteria promotions of new food items, and arranged for local sports mascots to visit the school to educate students about the importance of eating healthy. While formal data on the acceptability of the program among students and parents were not obtained, feedback was solicited through anonymous “How Are We Doing Healthy Watch” boxes placed in high traffic areas throughout the school and during registration; school staff report that about 90% of the feedback received was positive. The successful implementation of the Healthy Kids, Smart Kids program highlights the utility of a community-based participatory approach and the importance of developing and sustaining effective relationships between the principal, other school administrators and staff, teachers, parents, and children.

In 2004, the Child Nutrition and WIC Reauthorization Act required that local school districts develop a wellness policy by 2006, setting goals for nutrition education, physical activity and food provisions to address the epidemic of childhood obesity. Due to inconsistent responses by school districts, Congress directed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to undertake a study with the Institute of Medicine to review and make recommendations about appropriate nutritional standards for the availability, sale, and content of foods at school. Their report, Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools: Leading the Way toward Healthier Youth (31), concluded that 1) federally-reimbursable school nutrition programs should be the main source of nutrition at school, 2) opportunities for competitive foods should be limited, and 3) if competitive foods are available, they should consist of nutrient-dense foods including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and nonfat or low-fat milk and dairy products, consistent with the 2005 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. The Healthy Kids, Smart Kids program is consistent with these recommendations, and could serve as a feasible and sustainable model for the development of other schools' wellness policies.

To our knowledge, no study on nutrition and fitness related programs in schools has addressed the impact on school factors such as disciplinary referrals, nurse referrals, counseling referrals, or test scores. Findings from this analysis suggest the relevance of examining these outcomes in future school-based nutrition interventions. If prospective research indicates that healthful dietary change in the school facilitates achievement and social development outcomes, such findings would provide compelling support for further development and dissemination of such programs.

As the Healthy Kids, Smart Kids program was not implemented as part of a research study, there was no attempt to assess individual-level data or control for possible historical factors, and formal comparison data are not available. As such, it is not possible to determine the extent to which the observed positive trends were associated with the program. However, retrospective inquiry as to possible historical factors that may account for the findings yielded no major changes in educational approaches or other school-related factors. Importantly, there was an increase in the percent of students eligible for free or reduced price school lunches, indicating a decrease in socio-economic status across the years studied. As such, the observed improvements in school performance indicators are especially remarkable. In 2002, all schools were mandated to implement a mentoring program for students in single-parent homes and foster care. The increase in counseling referrals from 2001 to 2002 is believed to be attributable to this mandate. Additional limitations, due to the retrospective nature of the analyses, include the lack of data on actual dietary intake, students' BMI, and costs of program implementation (though no external funding was provided for this program), as well as specific data on acceptability of the program among students, parents, and staff.

As one of the first schools to eliminate highly processed foods and substitute more nutritious options, Browns Mill Elementary School serves as an example of a successful grass-roots effort to improve the healthfulness of the school environment with regard to food choices and physical activity. While other local grassroots efforts are occasionally reported in the media and other sources, little or no evaluation of such efforts have occurred. Findings from this retrospective analysis suggest that such an approach is promising. While the primary motivator for implementing programs such as the one described here is to impact student physical health, these efforts may improve school performance indicators as well.

Acknowledgments

This project received no external funding. Data analysis and manuscript preparation were supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The contents of this publication do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the National Institutes of Health. None of the authors possesses any conflicts of interest. Y.S.-B. led the development and implementation of the Health Kids, Smart Kids program and obtained the school data reported. T.R.N., A.J.R. and T.T.K.H. conceptualized the retrospective data analysis. T.R.N. conducted analyses and drafted the manuscript; all author contributed to critical revisions. Y.S.-B. wishes to acknowledge the contribution of the following individuals to the success of the Healthy Kids, Smart Kids program. Marilyn Hughes, PhD, RD, LD (nutrition research scientist) assisted with the development of the Healthy Kids, Smart Kids Program. Lorine Phillips Bizzell (public health nutritionist) analyzed recipes and provided technical assistance and resources for the Healthy Kids, Smart Kids Program. James L. Lawrence (fitness specialist) supported the physical activity format that promoted health and exercise throughout the school day.

References

- 1.Guenther PM, Dodd KW, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Most Americans eat much less than recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106(9):1371–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Munoz KA, Krebs-Smith SM, Ballard-Barbash R, Cleveland LE. Food intakes of US children and adolescents compared with recommendations. Pediatrics. 1997;100(3 Pt 1):323–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.100.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Subar AF, Krebs-Smith SM, Cook A, Kahle LL. Dietary sources of nutrients among US children, 1989-1991. Pediatrics. 1998;102(4):913–923. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.4.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden CL, Carrol MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puhl RM, Latner JD. Stigma, obesity, and the health of the nation's children. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:557–580. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.4.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh AS, Mulder C, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Chinapaw MJ. Tracking of childhood overweight into adulthood: a systematic review of the literature. Obesity Reviews. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00475.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li S, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, Bond MG, Tang R, Urbina EM, et al. Childhood cardiovascular risk factors and carotid vascular changes in adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;290(17):2271–2276. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frankel S, Gunnell DJ, Peters TJ, Maynard M, Smith GD. Childhood energy intake and adult mortality from cancer: the boyd orr cohort study. British Medical Journal. 1998;316(7130):499–504. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7130.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maynard M, Gunnell D, Emmett P, Frankel S, Davey SG. Fruit, vegetables, and antioxidants in childhood and risk of adult cancer: the boyd orr cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(3):218–25. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.3.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Correction: actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293(3):293–294. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.3.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S.Department of Health and Human Services . The surgeon general's call to action to prevent and decrease overweight and obesity. Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General; Rockville, MD: 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gleason P, Suitor C, US Food and Nutrition Service . Children's diets in the mid-a990s: dietary intake and its relationship with school meal participation. US Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; Alexandria, Virginia: 2001. CN-01-CD1. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cullen KW, Zakeri I. Fruits, vegetables, milk, and sweetened beverages consumption and access to a la carte / snack bar meals at school. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(3):463–467. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubik MY, Lytle LA, Hannan PJ, Perry CL, Story M. The association of the school food environment with dietary behaviors of young adolescents. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(7):1168–1173. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neumark-Sztainer D, French SA, Hannan PJ, Story M, Fulkerson JA. School lunch and snacking patterns among high school students: associations with school food environment and policies. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2005;2(14) doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-2-14. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.French SA, Wechsler H. School-based research and initiatives: fruit and vegetable environment, policy, and pricing workshop. Preventive Medicine. 2004;39:S101–S107. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cunningham-Sabo L, Snyder MP, Anliker J, Thompson J, Weber JL, Thomas O, et al. Impact of the Pathways food service intervention on breakfast served in American-Indian schools. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37:S46–S54. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Osganian SK, Ebzery MK, Montgomery DH, Nicklas TA, Evans MA, Mitchell PD, et al. Changes in the nutrition content of school lunches: results from the CATCH Eat Smart food service intervention. Preventive Medicine. 1996;25:400–412. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Story M, Snyder MP, Anliker J, Weber JL, Cunningham-Sabo L, Stone EJ, et al. Changes in the nutrient content of school lunches: results from the Pathways study. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37:S35–S45. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eriksen K, Haraldsdottir J, Pederson R, Flyger H. Effect of a fruit and vegetable subscription in Danish schools. Public Health Nutrition. 2003;6(1):57–63. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.French SA, Story M, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P. An environmental intervention to promote lower-fat food choices in secondary schools: outcomes of the TACOS study. Americal Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(9):1507–1512. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwartz MB. The influence of a verbal prompt on school lunch fruit consumption: a pilot study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2007;4(6) doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-6. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cullen KW, Watson K, Zakeri I. Improvements in middle school student dietary intake after implementation of the Texas public school nutrition policy. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(1):111–117. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.111765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ellison RC, Capper AL, Goldberg RJ, Witschi JC, Stare FJ. The environmental component: changing school food service to promote cardiovascular health. Health Education Quarterly. 1989;16(2):285–297. doi: 10.1177/109019818901600211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foster GD, Sherman S, Borradalle KE, Grundy KM, Vander Veur SS, Nachmani J, et al. A policy-based school intervention to prevent overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):e794–e802. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1365. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gordon A, Fox MK. Summary of findings. United States Department of AgricultureFood and Nutrition Service, Office of Research, Nutrition, and Analysis; Alexandria, VA: 2007. School nutrition dietary assessment study III. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nollen NL, Befort CA, Snow P, Daley CM, Ellerbeck EF, Ahluwalia JS. The school food environment and adolescent obesity: qualitative insights from high school principals and food service personnel. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2007;4(18) doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-18. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-4-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kretchmer N, Beard JL, Carlson S. The role of nutrition in the development of normal cognition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63(suppl 1):997–1001. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.6.997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taras H. Nutrition and student performance at school. Journal of School Health. 2003;75:199–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2005.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Florence MD, Asbridge M, Veugelers PJ. Diet quality and academic performance. Journal of School Health. 2008;78(4):209–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Institute of Medicine . Nutrition standards for foods in schools: leading the way toward healthier youth. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; Washington DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.US Department of Health and Human Services & US Department of Agriculture . Dietary Guidelines for Americans 1995. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1995. [Google Scholar]