Abstract

Chronic infection with Toxoplasma gondii is one of the most common parasitic infections in humans. Formation of tissue cysts is the basis of persistence of the parasite in infected hosts, and this cyst stage has generally been regarded as untouchable. Here we provide the first evidence that the immune system can eliminate T. gondii cysts from the brains of infected hosts when immune T cells are transferred into infected immunodeficient animals that have already developed large numbers of cysts. This T cell-mediated immune process was associated with accumulation of microglia and macrophages around tissue cysts. CD8+ immune T cells possess a potent activity to remove the cysts. The initiation of this process by CD8+ T cells does not require their production of interferon-γ, the major mediator to prevent proliferation of tachyzoites during acute infection, but does require perforin. These results suggest that CD8+ T cells induce elimination of T. gondii cysts through their perforin-mediated cytotoxic activity. Our findings provide a new mechanism of the immune system to fight against chronic infection with T. gondii and suggest a possibility of developing a novel vaccine to eliminate cysts from patients with chronic infection and to prevent the establishment of chronic infection after a newly acquired infection.

Toxoplasma gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite capable of infecting many warm-blooded mammals including humans. Acute infection is characterized by proliferation of tachyzoites and is known to cause various diseases including lymphadenitis and congenital infection of fetuses.1 Interferon (IFN)-γ-mediated immune responses limit proliferation of tachyzoites, but the parasite establishes a chronic infection by forming cysts, which can contain hundreds to thousands of bradyzoites, primarily in the brain. Chronic infection with T. gondii is one of the most common parasitic infections in humans. It is estimated that 5 × 108 people worldwide are chronically infected with this parasite.2 The tissue cysts remain largely quiescent for the life of the host, but can reactivate and cause life-threatening toxoplasmic encephalitis in immunocompromised patients, such as those with AIDS, neoplastic diseases and organ transplants.3,4 In immunocompetent individuals, recent studies suggested that T. gondii is an important cause of cryptogenic epilepsy,5,6 and is likely involved in the etiology of schizophrenia.7,8 The tissue cyst is not affected by any of the current drug treatments and it has been generally regarded as untouchable. However, the immune responses against T. gondii cysts remain largely unexplored.

Resistance to T. gondii is under genetic control in humans9,10 and mice.11,12 BALB/c mice are genetically resistant and have only small numbers of cysts in their brains at 2 to 3 months after infection.11,12 These mice may be able to prevent formation of cysts by efficiently controlling proliferation of tachyzoites during the acute stage of infection. However, it is also possible that the immune system of these animals has the capability to recognize T. gondii cysts and eliminate them from their brains. To examine whether immune cells have an activity to remove cysts that have already been formed in the brain, we adoptively transferred immune cells obtained from chronically infected BALB/c mice into infected, sulfadiazine-treated athymic nude or severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice, both of which lack T cells and developed large numbers of cysts in their brains. We present evidence for a potent capability of CD8+ immune T cells to eliminate T. gondii cysts from the brains through their perforin-mediated activity.

Materials and Methods

Mice

BALB/c-background IFN-γ-deficient (IFN-γ−/−), athymic nude, SCID, and wild-type BALB/c mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Swiss-Webster mice were from Taconic (Germantown, NY). BALB/c-background perforin-deficient (PO) mice13 were kindly provided by John T. Harty (University of Iowa) and bred in our animal facility. Mouse care and experimental procedures were performed under pathogen-free conditions in accordance with established institutional guidance and approved protocols from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Female mice were used for all studies. There were three to seven mice in each experimental group.

Infection with T. gondii

Cysts of the ME49 strain were obtained from brains of chronically infected Swiss-Webster mice.14 All animals were infected with 10 (for cell donors) or 20 (for cell recipients) cysts perorally by gavage. Mice were treated with sulfadiazine in the drinking water (400 mg/L) beginning at 4 days (for IFN-γ−/− mice), 7 to 9 days (for nude and SCID mice), or 26 days (PO mice) after infection for the entire period of experiment to control proliferation of tachyzoites and establish a chronic infection. IFN-γ−/− mice also received pyrimethamine (1 mg/0.2 ml) perorally by gavage once daily for 3 days before sacrifice to help ensure that their spleen cell preparations would not contain tachyzoites.

Purification and Transfer of Immune T Cells

Spleen cells were obtained from chronically infected (infected for more than 6 weeks) IFN-γ−/−, PO and wild-type mice, suspended in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) with 2% fetal bovine serum (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations were purified by treating the spleen cells with magnetic bead-conjugated anti-mouse CD4 (GK1.5) or anti-mouse CD8 (53–6.7) monoclonal antibodies (Mitenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA).15 Total T cell population was purified by treating the spleen cells with both monoclonal antibodies.16 The purity of the T cell population in each of the preparations was >95%. A total of 0.7 to 1 × 107 total T cells, or 2.1 to 3.5 × 106 CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were injected intravenously into recipient nude or SCID mice at 3 and/or 4 weeks after infection in most experiments.

Quantifying Numbers of T. gondii Cysts in the Brains of Recipient Mice

Seven days or 1 month (36 to 39 days) after the transfer of T cells, a half brain of each of the recipient nude or SCID mice was triturated in 0.5 or 1 ml of PBS. Numbers of cysts in two or three aliquots (20 μl each) of the brain suspensions were counted microscopically.

Semiquantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR for Detection of mRNA for Bradyzoite-Specific BAG1

Seven days or 1 month after the transfer of T cells, RNA was isolated from a half brain of each of the infected nude or SCID mice and cDNA was synthesized using the RNA as described previously.11,17 In the experiments with a transfer of CD8+ immune T cells from IFN-γ−/−, PO and wild-type BALB/c mice, the RNA were pretreated with DNase I (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) to remove genomic DNA contaminating the RNA preparations, and then applied for cDNA synthesis. PCR for β-actin and BAG1 were performed with 1 to 5 μl of diluted cDNA with GeneAmp PCR System 9700 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using 30 cycles of 94°C for 45 seconds, 60°C for 45 seconds, and 72°C for 1 minute and 20 seconds to produce an amount of DNA within a linear range.11,17 The dilutions of cDNA were determined in preliminary studies using different amounts of cDNA of the sample. The primers were 5′-GGGGTGGAGTCGGTCTTAAT-3′ (sense) and 5′-ATAACGATGGCTCCGTTGTC-3′ (antisense) for BAG1, and 5′-AGCCATGTACGTAGCCATCC-3′ (sense) and 5′- CTCTCAGCTGTGGTGGTGAA-3′ (antisense) for β-actin. In one experiment, another set of primers for β-actin11,17 was also used. Ten-microliter aliquots of the final PCR mixtures were electrophoresed at 100 V for 1 hour on a 1.5% agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide. The quantification of the PCR products was performed by densitometry analysis with Gel Logic 100 (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) and normalized to the β-actin level.

Histopathology

Two days after transfer of 0.7 × 107 normal or immune T cells, the infected recipient nude mice were euthanized and their brains were removed and immediately fixed in a solution containing 10% formalin, 70% ethanol, and 5% acetic acid. Five-micron-thick sagittal sections were stained with H&E. Immunoperoxidase staining using rabbit polyclonal anti-BAG 1 serum (kindly provided by Anthony Sinai of the University of Kentucky) was used for the detection of bradyzoites.18

Statistical Analysis

Levels of significance for numbers of cysts and the amount of BAG1 mRNA in the brains were determined by Student’s t, Alternate Welch t-test, or Mann-Whitney test. Alternative Welch t or Mann-Whitney test was applied when standard deviations were significantly different between groups tested. Differences which provided P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

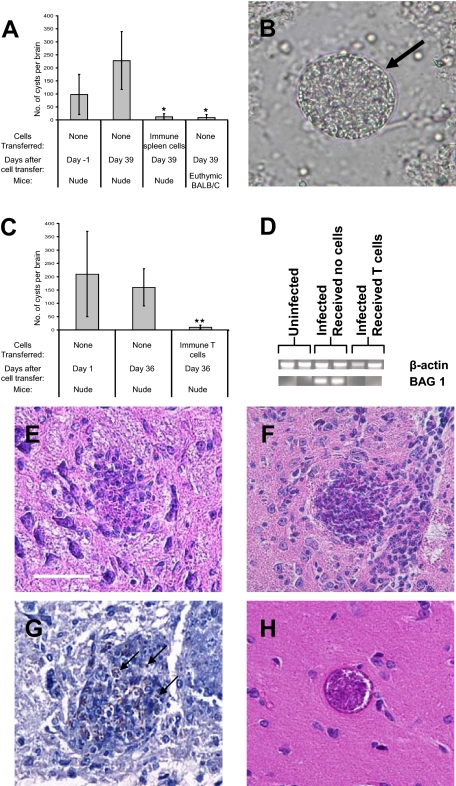

Adoptive Transfer of Immune Spleen Cells Reduces Numbers of T. gondii Cysts in the Brains of Chronically Infected Nude Mice

BALB/c-background nude mice were infected and treated with sulfadiazine to establish a chronic infection.15 Animals received 2 × 107 immune spleen cells obtained from chronically infected BALB/c mice at 3 and 4 weeks after infection. At 1 day before the first cell transfer (Day −1), large numbers of T. gondii cysts were detected in their brains (Figure 1, A and B). Each cyst had a typical cyst wall (Figure 1B, arrow), indicating they are the cyst stage of the parasite, rather than bradyzoite-infected cells. At 1 month after the second cell transfer (Day 39), the numbers of cysts in the brain were compared between the mice that had received the immune spleen cells and the control animals that had not received the cells. The numbers of T. gondii cysts in the brains of control mice (Day 39) tended to be greater than those at Day −1 (Figure 1A). In contrast, the brain cyst numbers in the animals that had received the immune spleen cells were markedly fewer than those in the control mice at Day −1 and Day 39 (P < 0.05; Figure 1A). These results suggest that the immune cells have the capability to remove T. gondii cysts that have already formed in the brain of infected mice.

Figure 1.

Immune spleen cells and T cells have the ability to reduce the numbers of cysts in the brains of recipient nude mice and the anti-cyst activity of immune T cells is associated with an accumulation of mononuclear cells on T. gondii cysts. Athymic nude mice were infected with 20 cysts of the ME49 strain perorally and treated with sulfadiazine15 beginning at 7 days after infection for the entire period of the observation. The animals received 2 × 107 of immune spleen cells (A) or 0.7 to 1 × 107 of immune T cells (C−G) obtained from chronically infected BALB/c mice at 3 and 4 weeks after infection. A: Numbers of cysts in the brains of infected nude mice at 1 day before the first cell transfer (Day −1) and 1 month after the second cell transfer (Day 39). As an additional control, euthymic BALB/c mice were infected, and numbers of cysts in their brains were examined at Day 39 without cell transfer. A half brain of each mouse was suspended in 0.5 ml of PBS and numbers of cysts in 60 μl (3 samples of 20 μl each) of the brain suspensions were counted microscopically. The data represent means ± SD. *P < 0.05 compared with control nude mice without cell transfer, Day −1 and Day 39. B: Representative cyst detected at Day −1. Each cyst detected had a typical cyst wall (arrow). C: Numbers of cysts in the brains of infected nude mice at one day after the first cell transfer (Day 1) and 1 month after the second cell transfer (Day 36). The data represent means ± SD. The data shown are representative of four independent experiments. **P < 0.01 compared with control nude mice without cell transfer, Day 1 and Day 36. D: Reverse transcription-PCR detecting mRNA for bradyzoite-specific BAG1 at Day 39. E−G: Accumulation of mononuclear cells on and within T. gondii cysts in the brains of infected nude mice at 2 days after a transfer of immune T cells (0.7 × 107 cells) (n = 3). E and F: H&E stain. Scale bar = 50 μm. G: Immunostaining for BAG1 to detect bradyzoites (some are highlighted with arrows). H: A representative of T. gondii cysts observed in the brains of nude mice that had received normal T cells (n = 2) or those that had not received any T cells (n = 2) (H&E stain). At least five sections (25 μm or more distance between sections) were examined on each brain sample.

Immune T Cells Remove T. gondii Cysts from the Brains of Chronically Infected Mice

To determine the cell population that has an activity to remove T. gondii cysts, we examined whether T cells have the protective activity against cysts. Immune T cells purified from spleens of chronically infected BALB/c mice were transferred into infected, sulfadiazine-treated nude mice as described above. At 1 month after the second cell transfer (Day 36), numbers of cysts in the brains of the animals that had received immune T cells were significantly fewer than those observed in the brains of control mice without the cell transfer at the time of one day after the first cell transfer (Day 1) and Day 36 (P < 0.01; Figure 1C). In contrast, numbers of cysts in brains did not differ between Days 1 and 36 in the control mice that had not received any immune cells (Figure 1C). Consistent with the marked reduction of cyst numbers in the brains of animals that had received immune T cells, amounts of mRNA for bradyzoite (the stage of the parasite located within tissue cysts)-specific BAG1 were markedly less in the brains of mice that had received the T cells than those that had not received any cells (Figure 1D). The reduction of cyst number did not require 1 month after transferring T cells. Even 7 days after the cell transfer, numbers of cysts in the brains were significantly fewer in mice that had received immune T cells than those in animals that had not received any T cells or those in animals that had received normal T cells (P < 0.05; Table 1). These results indicate that immune T cells have a potent activity to remove T. gondii cysts from the brains of mice within a short period of time, 7 days.

Table 1.

Immune T Cells Can Reduce Numbers of T. gondii Cysts within 7 Days in the Brains of the Recipient Nude Mice

| Mice | Number of mice | Cells transferred | Number of cysts* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nude | 4 | None | 9, 8, 77, 12 |

| Nude | 4 | Normal T cells† | 10, 2, 8, 2 |

| Nude | 5 | Immune T cells‡ | 0, 0, 1, 2, 0 (P < 0.05)§ |

A half brain of each mouse was suspended in 1 ml of PBS and 40 μl of the suspension was examined microscopically.

Purified from uninfected BALB/c mice.

Purified from chronically infected BALB/c mice.

When compared with the other two groups.

Immune T Cells Induce Accumulation of Microglia and Macrophages Around T. gondii Cysts in the Brain

Histological studies were performed on the brains of infected, sulfadiazine-treated nude mice at 2 days after receiving normal or immune T cells. An accumulation of mononuclear cells, primarily microglia and macrophages morphologically, around T. gondii cysts was observed in the brains of the recipients of immune T cells. We detected cysts partially covered (Figure 1E) or totally covered (Figure 1F) by microglia and macrophages. Immunostaining for bradyzoite-specific BAG1 showed that microglia and macrophages accumulated around the parasite positive for BAG1, indicating that the cyst stage of the parasite is the target of these phagocytes (Figure 1G). The immunostaining also showed that the accumulated phagocytes penetrated within the cyst (Figure 1G). Infiltration of T cells and microglia/macrophages was confirmed by immunohistochemistry detecting both CD3+ cells and F4/80+ cells adjacent to a T. gondii cyst (data not shown). We did not observe such cysts associated with accumulation of inflammatory cells in the brains of control mice that had received normal T cells or no T cells (Figure 1H). These results indicate that immune T cells have the activity to induce an accumulation of microglia and macrophages on T. gondii cysts in the brain. Accumulated microglia and macrophages appear to be the main effector cells that destroy T. gondii cysts and eliminate them from the brain after initiation of this process by immune T cells.

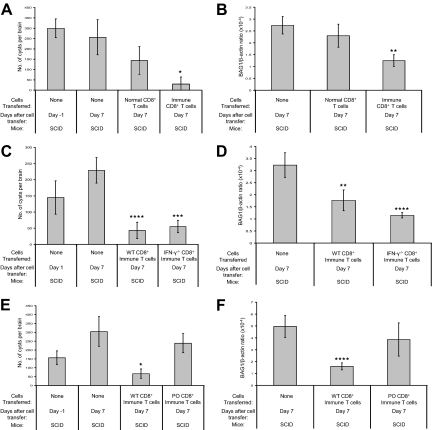

CD8+ Immune T Cells Possess a Potent Activity to Remove T. gondii Cysts from the Brain

We next examined whether CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, or both, have the activity against T. gondii cysts. For this purpose, we used SCID mice, which lack both T and B cells, as recipients of cell transfer. In this way, we can exclude a possible T cell-assisted involvement of B cells in the cyst elimination. Infected and sulfadiazine-treated SCID mice received CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from either uninfected or infected BALB/c mice at 4 weeks after infection. Numbers of brain cysts in the control animals that had not received any T cells did not differ between one day before and 7 days after the cell transfer (Figure 2A). The brain cyst numbers in mice that had received normal CD8+ T cells tended to be a little fewer than those in the control animals without cell transfer but the difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 2A). In contrast, the cyst numbers in the animals that had received the immune CD8+ T cells were markedly fewer (Figure 2A) when compared with the control animals without the cell transfer (P < 0.005) and those that had received normal CD8+ T cells (P < 0.05). Mice that had received either normal or immune CD4+ T cells from infected animals had fewer cysts than the control mice (P < 0.05), but cyst numbers in mice that had received CD4+ immune T cell were three times greater than those of recipients of CD8+ immune T cells (data not shown). In addition, there were no differences in the cyst numbers between the recipients of normal and immune CD4+ cells. These results indicate that immune CD8+ T cells have a potent activity to induce elimination of T. gondii cysts, and CD4+ T cells seem to possess a similar activity to a lesser extent. Reverse transcription-PCR semiquantifying amounts of mRNA for bradyzoite-specific BAG1 confirmed a significant reduction of T. gondii cysts in the brains of mice that had received immune CD8+ T cells (Figure 2B; P < 0.0005).

Figure 2.

CD8+ T cells remove T. gondii cysts from the brains of recipient nude mice and their protective activity does not require IFN-γ but requires perforin. A: Numbers of T. gondii cysts and (B) the amounts of BAG1 mRNA in the brains of infected, sulfadiazine-treated SCID mice at 1 day before and 7 days after a transfer of normal or immune CD8+ T cells (3.5 × 106 cells) from uninfected or chronically infected BALB/c mice. The cell transfer was performed at 3 weeks after infection. C: Numbers of T. gondii cysts and (D) the amounts of BAG1 mRNA in the brains of infected, sulfadiazine-treated SCID mice at 1 and 7 days after a transfer of CD8+ immune T cells (2.1 × 106 cells) from infected IFN-γ−/− or wild-type BALB/c mice. E: Numbers of T. gondii cysts and (F) the amounts of BAG1 mRNA in the brains of infected, sulfadiazine-treated SCID mice at 1 day before and 7 days after a transfer of CD8+ immune T cells (2.1 × 106 cells) from infected perforin-deficient (PO) or wild-type BALB/c mice. All data represent mean ± SD. The data shown in (E) are representative of two independent experiments. *P < 0.005, **P < 0.0005, ***P = 0.0001, ****P < 0.0001 compared with control nude mice without cell transfer, Day 7.

IFN-γ Production by CD8+ T Cells Is Not Required for Their Protective Activity to Induce Removal of T. gondii Cysts from the Brain

For understanding the mechanism of CD8+ T cell-mediated elimination of the cyst stage of T. gondii, it is important to determine the function(s) of T cells required for this anti-cyst protective activity. IFN-γ has been shown to play the central role for controlling proliferation of tachyzoites during the acute stage of infection,19,20,21 and for preventing the development of toxoplasmic encephalitis caused by proliferation of tachyzoites in the brain during the later stage of infection.22,23,24 Therefore, this cytokine may also play an important role in the activity of immune CD8+ T cells against the cyst stage of the parasite. On the other hand, in vitro studies have shown that long-term culturing of T. gondii cysts can be accomplished within infected astrocytes in the presence of IFN-γ.25 To examine whether IFN-γ plays an important role in the protective activity of immune CD8+ T cells against the cysts, infected, sulfadiazine-treated SCID mice received immune CD8+ T cells from either infected IFN-γ−/− or wild-type BALB/c mice at 3 weeks after infection. At 1 week after the cell transfer, cyst numbers were markedly fewer in the mice that had received immune CD8+ T cells from either wild-type or IFN-γ−/− donors than in the control animals that had not received any T cells (Figure 2C; P < 0.0001 and P = 0.0001, respectively). There were no differences in numbers of brain cysts in the mice that had received wild-type or IFN-γ−/− CD8+ T cells (Figure 2C). The marked reduction of brain cysts in the recipients of these CD8+ T cell populations was confirmed by reverse transcription-PCR detecting BAG1 mRNA (Figure 2D; P < 0.0005). These results indicate that IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells is not required for their protective activity to induce elimination of T. gondii cysts from the brain.

Perforin Is Required for the Protective Activity of CD8+ T Cells to Remove T. gondii Cysts from the Brain

Human and mouse CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are capable of lysing tachyzoite-infected target cells in vitro in a major histocompatibility complex-restricted manner.26,27,28,29 Although two studies have shown that perforin-deficient mice survive acute infection,24,30 perforin-mediated cytotoxic activity of CD8+ T cells may play a previously unappreciated but important role against tissue cysts during the later stage of infection. To address this possibility, we transferred immune CD8+ T cells from infected PO or wild-type mice into infected, sulfadiazine-treated SCID mice. At 1 week after the cell transfer, numbers of cysts were significantly less in the brains of animals that had received immune CD8+ T cells from wild-type donors than in control mice that had not received any T cells (Figure 2E, P < 0.005). In contrast, brain cyst numbers of animals that had received immune CD8+ T cells from PO mice were equivalent to those of the control animals without cell transfer (Figure 2E). Reverse transcription-PCR detecting mRNA for BAG1 confirmed a significant reduction of brain cysts only in the recipients of wild-type CD8+ T cells (Figure 2F; P < 0.0001). These results indicate that perforin is required for the protective activity of CD8+ T cells to induce elimination of T. gondii cysts from the brain of infected mice. Thus, perforin-mediated cytotoxic activity of CD8+ T cells appears to be crucial to remove T. gondii cysts from the brains.

Discussion

The present study provides the first evidence for the capability of the immune system and CD8+ T cells to eliminate T. gondii cysts from the brains of infected hosts. Of importance, the anti-cyst activity of CD8+ T cells is mediated by perforin, not IFN-γ. Perforin is the major molecule that mediates cytolysis of target cells by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells. Since T. gondii cysts reside within infected cells,31,32 cytolysis of the cyst-containing cells by perforin-mediated cytotoxic activity of CD8+ T cells appears to induce removal of the cysts. Kim and Boothroyd33 previously reported that when mice were infected intraperitoneally with tachyzoites engineered to constitutively express SRS9, a bradyzoite-specific antigen, in both tachyzoite and bradyzoite stages, spleen cells of the infected animals produced IFN-γ in response to SRS9 and that cyst numbers in their brains decreased in later stage of infection. However, in their studies, it was not clear whether the decrease in cyst numbers was due to the immune responses or a shorter life span of cysts of the genetically engineered parasite. Blackwell et al34 also reported that numbers of cysts in the brains of BALB/c mice gradually increased until 35 days after infection and thereafter decreased at 77 days after infection. These decreases in cyst numbers in the previous studies could be, at least in part, due to the perforin-mediated anti-cyst activity of CD8+ T cells observed in the present study. Ferguson et al35 previously noted that brain cysts occasionally rupture in immunocompetent mice during the chronic stage of infection. The observed cyst ruptures may have been mediated by the anti-cyst activity of CD8+ T cells.

In resistance against T. gondii, the absolute requirement of IFN-γ to control tachyzoite proliferation during the acute stage of infection has been well documented.19,20,21 In contrast, perforin-mediated cytolytic activity of T cells was less appreciated before. Perforin-knockout mice survive acute infection as mentioned earlier.24,30 In vitro studies demonstrated that the lysis of tachyzoite-infected cells by cytotoxic CD8+ T cells results in release of viable parasites.36 However, the situation of the parasite in the cyst stage seems different. Whereas the cyst resides within an infected cell31,32 as do tachyzoites, bradyzoites within the cyst are surrounded by a thick cyst wall, which is unique to the cyst. Therefore, cytolysis of cyst-containing cells by perforin-mediated activity of CD8+ T cells followed by quick accumulation of large numbers of microglia and macrophages would probably provide the parasite little time to escape from the coordinated attack by the T cells and phagocytes. Denkers et al30 previously reported a three- to fourfold increase in brain cyst numbers in perforin-knockout mice in the later stage of infection. Although the mechanisms underlying the increased cyst numbers were unclear at that time, the absence of perforin-dependent anti-cyst activity of CD8+ T cells in these animals may have contributed to their observation.

By infecting C57BL/6 mice with ovalbumin-expressing T. gondii, Schaeffer et al37 recently reported that ovalbumin-specific CD8+ T cells accumulated in regions containing isolated parasites (tachyzoites) but not around cysts in the brain. C57BL/6 mice are genetically susceptible to chronic infection with the parasite and develop large numbers of cysts in their brains. Therefore, it is possible that CD8+ T cells of these animals do not have a potent anti-cyst activity, in contrast to the T cells of genetically resistant BALB/c mice as observed in the present study.

During the T cell-mediated anti-cyst activity, microglia and macrophages accumulated on the cysts, and these phagocytes appear to be the main effector cells that destroy T. gondii cysts. IFN-γ has been shown to be the major activator of microglia and macrophages to prevent proliferation of T. gondii tachyzoites.19,38 Although the present study demonstrated that IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells is not required to induce removal of T. gondii cysts from the brain, it is possible that IFN-γ produced by cells other than T cells contributes to activating microglia and macrophages for their anti-cyst activity. We previously reported that microglia and blood-derived macrophages produce IFN-γ in the brains of nude and SCID mice following T. gondii infection.39,40 NK cells are also known to produce this cytokine following infection.41,42 One cyst can contain hundreds to thousands of bradyzoites. During destruction of tissue cysts by perforin-mediated activity of CD8+ T cells and the phagocytes, a leak of bradyzoites could result in their conversion to tachyzoites. Although IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells is not required for destruction of cysts as shown in the present study, IFN-γ production by CD8+ T cells might play a role in preventing subsequent proliferation of tachyzoites in surrounding cells (eg, astrocytes).43 In this regard, we measured amounts of mRNA for tachyzoite-specific SAG1 in the brains of SCID mice that had received CD8+ T cells from IFN-γ−/− or wild-type mice at 7 days after cell transfer. We detected slightly higher amounts of SAG1 mRNA in the recipients of IFN-γ−/− CD8+ T cells than in those of wild-type CD8+ T cells but the difference was not statistically significant (data not shown). This point may need to be further analyzed.

The results in the present study indicate that perforin-mediated activity of CD8+ T cells can induce elimination of the cyst stage of T. gondii when the T cells are activated appropriately. This information opens a door for possible development of a novel vaccine to eliminate cysts from chronically infected individuals. This vaccine would also be able to prevent formation of tissue cyst and establishment of chronic infection with T. gondii following newly acquired infection. With combination of these two effects, we may be able to eradicate T. gondii infection, which is one of the most common parasitic infections of humans worldwide. The vaccine against the cyst stage of T. gondii appears to be a powerful strategy to fight against this parasite.

Acknowledgments

We thank Glenn Telling and Guangxiang Luo for reading the manuscript and providing helpful suggestions and Jerry Baber for his assistance for preparing figures.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Yasuhiro Suzuki, Ph.D., Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Molecular Genetics, University of Kentucky College of Medicine, 800 Rose Street, Lexington, KY 40536. E-mail: yasu.suzuki@uky.edu.

Supported by grants from National Institutes of Health (AI073576, AI078756, and AI077877) (to Y.S.).

Current address of X.W.: Center for Pulmonary and Infectious Disease Control, University of Texas Health Science Center at Tyler.

References

- McCabe RE, Remington JS. Toxoplasma gondii. Mandell GL, Douglas RG, Bennett JE, editors. New York,: Churchill Livingstone Inc.,; 1990:p. 2090–2103. [Google Scholar]

- Denkers EY, Gazzinelli RT. Regulation and function of T-cell-mediated immunity during Toxoplasma gondii infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:569–588. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israelski DM, Remington JS. Toxoplasmosis in the non-AIDS immunocompromised host. Remington JS, Swrltz M, editors. London,: Blackwell Scientific Publications,; 1993:pp. 322–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong SY, Remington JS. Toxoplasmosis in the setting of AIDS. Broder S, Merga TC Jr, Bolognesi D, editors. Baltimore,: Williams & Wilkins,; 1994:pp. 223–257. [Google Scholar]

- Yazar S, Arman F, Yalcin S, Demirtas F, Yaman O, Sahin I. Investigation of probable relationship between Toxoplasma gondii and cryptogenic epilepsy. Seizure. 2003;12:107–109. doi: 10.1016/s1059-1311(02)00256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stommel EW, Seguin R, Thadani VM, Schwartzman JD, Gilbert K, Ryan KA, Tosteson TD, Kasper LH. Cryptogenic epilepsy: an infectious etiology? Epilepsia. 2001;42:436–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.25500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrey EF, Bartko JJ, Lun ZR, Yolken RH. Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33:729–736. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HL, Wang GH, Li QY, Shu C, Jiang MS, Guo Y. Prevalence of Toxoplasma infection in first-episode schizophrenia and comparison between Toxoplasma-seropositive and Toxoplasma-seronegative schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114:40–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Wong SY, Grumet FC, Fessel J, Montoya JG, Zolopa AR, Portmore A, Schumacher-Perdreau F, Schrappe M, Koppen S, Ruf B, Brown BW, Remington JS. Evidence for genetic regulation of susceptibility to toxoplasmic encephalitis in AIDS patients. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:265–268. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack DG, Johnson JJ, Roberts F, Roberts CW, Estes RG, David C, Grumet FC, McLeod R. HLA-class II genes modify outcome of Toxoplasma gondii infection. Int J Parasitol. 1999;29:1351–1358. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(99)00152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Joh K, Kwon OC, Yang Q, Conley FK, Remington JS. MHC class I gene(s) in the D/L region but not the TNF-alpha gene determines development of toxoplasmic encephalitis in mice. J Immunol. 1994;153:4649–4654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CR, Hunter CA, Estes RG, Beckmann E, Forman J, David C, Remington JS, McLeod R. Definitive identification of a gene that confers resistance against Toxoplasma cyst burden and encephalitis. Immunology. 1995;85:419–428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DW, MacNeil A, Busch DH, Pilip IM, Pamer EG, Harty JT. Perforin-deficient CD8+ T cells: in vivo priming and antigen-specific immunity against Listeria monocytogenes. J Immunol. 1999;162:980–988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Orellana MA, Wong SY, Conley FK, Remington JS. Susceptibility to chronic infection with Toxoplasma gondii does not correlate with susceptibility to acute infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2284–2288. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2284-2288.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H, Suzuki Y. Requirement of non-T cells that produce gamma interferon for prevention of reactivation of Toxoplasma gondii infection in the brain. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2920–2927. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.2920-2927.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Claflin J, Kang H, Suzuki Y. Importance of CD8(+)Vbeta8(+) T Cells in IFN-gamma-mediated prevention of toxoplasmic encephalitis in genetically resistant BALB/c mice. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2005;25:338–344. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Yang Q, Yang S, Nguyen N, Lim S, Liesenfeld O, Kojima T, Remington JS. IL-4 is protective against development of toxoplasmic encephalitis. J Immunol. 1996;157:2564–2569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conley FK, Jenkins KA, Remington JS. Toxoplasma gondii infection of the central nervous system. Use of the peroxidase-antiperoxidase method to demonstrate toxoplasma in formalin fixed, paraffin embedded tissue sections. Hum Pathol. 1981;12:690–698. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(81)80170-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Orellana MA, Schreiber RD, Remington JS. Interferon-gamma: the major mediator of resistance against Toxoplasma gondii. Science. 1988;240:516–518. doi: 10.1126/science.3128869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Remington JS. Dual regulation of resistance against Toxoplasma gondii infection by Lyt-2+ and Lyt-1+ L3T4+ T cells in mice. J Immunol. 1988;140:3943–3946. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzinelli RT, Hakim FT, Hieny S, Shearer GM, Sher A. Synergistic role of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in IFN-gamma production and protective immunity induced by an attenuated Toxoplasma gondii vaccine. J Immunol. 1991;146:286–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzinelli R, Xu Y, Hieny S, Cheever A, Sher A. Simultaneous depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes is required to reactivate chronic infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1992;149:175–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Conley FK, Remington JS. Importance of endogenous IFN-gamma for prevention of toxoplasmic encephalitis in mice. J Immunol. 1989;143:2045–2050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Kang H, Kikuchi T, Suzuki Y. Gamma interferon production, but not perforin-mediated cytolytic activity, of T cells is required for prevention of toxoplasmic encephalitis in BALB/c mice genetically resistant to the disease. Infect Immun. 2004;72:4432–4438. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.8.4432-4438.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TC, Bienz KA, Erb P. In vitro cultivation of Toxoplasma gondii cysts in astrocytes in the presence of gamma interferon. Infect Immun. 1986;51:147–156. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.1.147-156.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curiel TJ, Krug EC, Purner MB, Poignard P, Berens RL. Cloned human CD4+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes specific for Toxoplasma gondii lyse tachyzoite-infected target cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:2024–2031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakim FT, Gazzinelli RT, Denkers E, Hieny S, Shearer GM, Sher A. CD8+ T cells from mice vaccinated against Toxoplasma gondii are cytotoxic for parasite-infected or antigen-pulsed host cells. J Immunol. 1991;147:2310–2316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan IA, Smith KA, Kasper LH. Induction of antigen-specific parasiticidal cytotoxic T cell splenocytes by a major membrane protein (P30) of Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1988;141:3600–3605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya JG, Lowe KE, Clayberger C, Moody D, Do D, Remington JS, Talib S, Subauste CS. Human CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes are both cytotoxic to Toxoplasma gondii-infected cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:176–181. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.176-181.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denkers EY, Yap G, Scharton-Kersten T, Charest H, Butcher BA, Caspar P, Heiny S, Sher A. Perforin-mediated cytolysis plays a limited role in host resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1997;159:1903–1908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson DJ, Hutchison WM. An ultrastructural study of the early development and tissue cyst formation of Toxoplasma gondii in the brains of mice. Parasitol Res. 1987;73:483–491. doi: 10.1007/BF00535321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatak NR, Zimmerman HM. Fine structure of Toxoplasma in the human brain. Arch Pathol. 1973;95:276–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Boothroyd JC. Stage-specific expression of surface antigens by Toxoplasma gondii as a mechanism to facilitate parasite persistence. J Immunol. 2005;174:8038–8048. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.8038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell JM, Roberts CW, Alexander J. Influence of genes within the MHC on mortality and brain cyst development in mice infected with Toxoplasma gondii: kinetics of immune regulation in BALB H-2 congenic mice. Parasite Immunol. 1993;15:317–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1993.tb00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson DJ, Hutchison WM, Pettersen E. Tissue cyst rupture in mice chronically infected with Toxoplasma gondii. An immunocytochemical and ultrastructural study. Parasitol Res. 1989;75:599–603. doi: 10.1007/BF00930955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita K, Yui K, Ueda M, Yano A. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-mediated lysis of Toxoplasma gondii-infected target cells does not lead to death of intracellular parasites. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4651–4655. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4651-4655.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeffer M, Han SJ, Chtanova T, van Dooren GG, Herzmark P, Chen Y, Roysam B, Striepen B, Robey EA. Dynamic imaging of T cell-parasite interactions in the brains of mice chronically infected with Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 2009;182:6379–6393. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao CC, Anderson WR, Hu S, Gekker G, Martella A, Peterson PK. Activated microglia inhibit multiplication of Toxoplasma gondii via a nitric oxide mechanism. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1993;67:178–183. doi: 10.1006/clin.1993.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Claflin J, Wang X, Lengi A, Kikuchi T. Microglia and macrophages as innate producers of interferon-gamma in the brain following infection with Toxoplasma gondii. Int J Parasitol. 2005;35:83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Suzuki Y. Microglia produce IFN-gamma independently from T cells during acute toxoplasmosis in the brain. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2007;27:599–605. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzinelli RT, Hieny S, Wynn TA, Wolf S, Sher A. Interleukin 12 is required for the T-lymphocyte-independent induction of interferon gamma by an intracellular parasite and induces resistance in T-cell-deficient hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6115–6119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter CA, Subauste CS, Van Cleave VH, Remington JS. Production of gamma interferon by natural killer cells from Toxoplasma gondii-infected SCID mice: regulation by interleukin-10, interleukin-12, and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2818–2824. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2818-2824.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halonen SK, Chiu F, Weiss LM. Effect of cytokines on growth of Toxoplasma gondii in murine astrocytes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4989–4993. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4989-4993.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]