Abstract

Primary cell cultures from renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and normal renal cortex tissue of 60 patients have been established, with high efficiency (more than 70%) and reproducibility, and extensively characterized. These cultures composed of more than 90% of normal or tumor tubular cells have been instrumental for molecular characterization of Annexin A3 (AnxA3), never extensively studied before in RCC cells although AnxA3 has a prognostic relevance in some cancer and it has been suggested to be involved in the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 pathway. Western blot analysis of 20 matched cortex/RCC culture lysates showed two AnxA3 protein bands of 36 and 33 kDa, and two-dimensional Western blot evidenced several specific protein spots. In RCC cultures the 36-kDa isoform was significantly down-regulated and the 33-kDa isoform up-regulated. Furthermore, the inversion of the quantitative expression pattern of two AnxA3 isoforms in tumor cultures correlate with hypoxia-inducible factor-1α expression. The total AnxA3 protein is down-regulated in RCC cultures as confirmed also in tissues by tissue microarray. Two AnxA3 transcripts that differ for alternative splicing of exon III have been also detected. Real-time PCR quantification in 19 matched cortex/RCC cultures confirms the down-regulation of longer isoform in RCC cells. The characteristic expression pattern of AnxA3 in normal and tumor renal cells, documented in our primary cultures, may open new insight in RCC management.

Renal-cell carcinomas (RCC) arise from the renal epithelium, account for about 85% of renal cancers, and are characterized by different subtypes having different incidences. The clear-cell (RCCcc) and papillary (RCCpap) subtypes of sporadic RCC account for about 75% and 12% of cases, respectively, and have distinct genetic abnormalities.1 About 80% of RCCcc sporadic cases have a biallelic inactivation of von-Hippel Lindau (VHL) gene (VHL−/−)2 and a consequent hypoxia-independent increase of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) protein level.3 The molecular analysis of these tumors may be complicated because of the mixture of neoplastic and normal cells.4 Primary cell cultures of RCC and normal renal tissue have proven to be valuable in solving this problem and provide a good quality and quantity of homogeneous cellular material that can also be well characterized. Moreover, this in vitro model retains the same phenotype of the corresponding original tissue during the first passages.5 The reliability of data obtained with primary cultures is linked to the detailed characterization of their cellular composition, particularly regarding cellular contamination that can influence data interpretation. In the attempt to identify the differences between normal and renal tumor cells for the study of the molecular changes associated with the neoplastic status, we currently establish and characterize primary cell cultures. Our well characterized in vitro model has been instrumental for the molecular characterization of the Annexin A3 (AnxA3) gene product. AnxA3 is a member of a calcium-binding protein family, involved in membrane trafficking, leukocyte migration, and inflammatory response.6 AnxA3 was recently described as a candidate biomarker in different tumors like lung adenocarcinoma7 and prostate cancer,8 and it is over-expressed in colorectal tumor tissue9 and in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.10 In addition AnxA3 has been described to be involved in the enhancement of the transactivating activity of HIF-1 and in consequent angiogenesis.11 Interestingly, different isoforms of AnxA3, differentially expressed in different cell types, have been also described. In the HL-60 myeloid cell line, isoforms of 36 and 33 kDa have been detected, and when these cells were differentiated along the neutrophilic or the monocytic pathway they mainly expressed the 33-kDa form as in blood neutrophils or the 36-kDa form as in monocytes, respectively.12 The 36-kDa and 33-kDa isoforms are present in rat brain, and the 33-kDa form increases after stroke.13 However, in the neoplastic setting only the presence of the 36-kDa isoform of AnxA3 has been described until now. Thus, considering that there are very limited data concerning AnxA3 in kidney and RCC14 and that deregulation of HIF pathways plays a key role in the pathogenesis of RCCcc,3 we initiated the study of AnxA3 in primary cell cultures of RCC and normal cortex. With the combination of different technical approaches we demonstrated a differential expression pattern, correlated with HIF-1α expression, of two AnxA3 isoforms originating by an alternative splicing of exon III in RCC and normal renal tubular cells.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Sixty consecutive nonselected RCC patients treated by surgery were enrolled in this study after written consent. All procedures were approved by the Local Ethics Committee. The clinical-pathological characteristics of patients are reported in Table 1A. Histological types, grade, and tumor stage were defined according to World Health Organization classification and included 50 RCCcc, 8 RCCpap, and 2 mixed types (RCCcc and RCCpap).

Table 1.

Clinical-Pathological Characteristics of Study Population and Primary Cultures Obtained

| A: Study Population | Surgical samples

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortex | RCC | Matched samples (RCC-cortex) | ||

| Patients | 60 | 54 | 60 | 54 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 39 | |||

| Female | 21 | |||

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 61.9 ± 10.4 | |||

| Median (range)

|

61.5 (33–85)

|

|

|

|

| B: Primary Cultures | Primary cell cultures

|

|||

|

|

|

Cortex

|

RCC

|

Matched cultures (RCC-cortex)

|

| Cultures/surgical samples (efficiency %) | 50/54 (93%) | 44/60 (73%) | 38/54 (72%) | |

| Histological type | ||||

| RCCcc | 50 | 34 | 31 | |

| RCCpap | 8 | 8 | 5 | |

| RCCmix | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| G1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| G2 | 39 | 28 | 25 | |

| G3 | 9 | 7 | 5 | |

| Tumor stage | ||||

| pT1 | 40 | 29 | 24 | |

| pT2 | 8 | 7 | 7 | |

| pT3 | 12 | 8 | 7 | |

| Tumor size, cm | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 5.6 ± 3.1 | 5.5 ± 3.2 | 5.7 ± 3.4 | |

| Median (range) | 5 (0.8–18) | 4.8 (0.8–18) | 5 (0.8–18) | |

Primary Cell Cultures

Autologous tumor and cortex renal tissue specimens were collected, after surgery, in cold DMEM LG medium containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% amphotericin, 1% glutamine, and 10% fetal calf serum (Culture Medium) and kept at 4°C until processing (within 24 hours). Tissues, normal or neoplastic, were washed two times in PBS pH 7.2 at 4°C and minced in 1 mm3 fragments in a Petri dish. The small fragments were then incubated for 2 hours at 37°C with DMEM-F12 and 1.25 mg/ml Collagenase type IV (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and vigorously vortexed every 15 minutes to obtain enzymatic disaggregation. The samples were then washed three times in PBS at 4°C, plated in 10-cm Petri dishes in Culture Medium, and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2. After 24 hours the cells were washed with PBS at 37°C to remove erythrocytes, granulocytes, and apoptotic and necrotic cells, and the medium was then replaced. Cells were trypsinized when 90% confluent and split 1:3. All experiments were conducted on cells at first passages. The culture doubling times were calculated as described.15 Cell morphology was observed in contrast phase using an Inverted Olympus CK40 microscope at ×40 magnification.

Flow-Cytometric Analysis

Cells detached from plates with trypsin, washed with PBS and incubated for 15 minutes with PBS supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated calf serum to block non-pecific sites, were incubated for 15 minutes at RT with the specific antibody appropriately diluted. Staining of cytoplasmic antigens was performed using DAKO IntraStain solution (Dako, Glostrup, DK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. When a secondary antibody was needed, cells were stained by addition of Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (dilution 1:100; Molecular Probes Invitrogen, Carlsberg, CA) and were incubated for an additional 30 minutes at 4°C. A FACSCanto instrument and FACS Diva software (Becton Dickinson, San Josè, CA) were used. The acquisition process was stopped when 30,000 events were collected in the population gate. The mouse monoclonal anti-human antibodies (mAb) used were against: vimentin (clone V9, Dako), carbonic anhydrase IX (CA9; clone M75, a kind gift from Silvia Pastorekova, Slovak Acad Sci, Bratislava), CD31 (Clone WM-59, Sigma Aldrich), α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA; clone 1A4, Abcam, Cambridge, MA); the PE-conjugated antibodies were against CD11b (clone Bear1, Coulter, Fullerton, CA), pancytokeratin (clone C-11, EXBIO, Praha, Czech Republic), and CD13 (clone 22A5, IQProducts, Groninger, The Netherlands), and the FITC-conjugated was against CD14 (clone RMO52, Coulter).

Immunocytofluorescence Microscopy

Cells grown on glass coverslips were fixed for 30 minutes in 4% paraformaldehyde and pre-incubated for 15 minutes in G dilution buffer (PBS containing 0.45 mol/L NaCl, 1% BSA) containing 0.3% Triton X-100. The cells were then incubated for two hours at room temperature with G dilution buffer plus mAb respectively against pancytokeratin (dilution 1:200; clone MNF 116, Dako), vimentin (dilution 1:200), CA9 (dilution 1:50), calbindin-D28K (dilution 1:200, clone CB-955, Sigma-Aldrich), CD31 (dilution 1:50), α-SMA (dilution 1:75), the FITC-conjugated mAb against CD13 (dilution 1:25, clone CBL 169F, Chemicon, Billerica, MA), and rabbit polyclonal anti-Wilm Tumor 1 (WT1) protein (dilution 1:50; Santa Cruz, Heidelberg, Germany). After washing thoroughly with PBS, coverslips were incubated for one hour with Alexa Fluor 488 or 555 conjugated anti-mouse or 594 conjugated anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (dilution 1:100; Molecular Probes Invitrogen). Nuclear counterstaining was obtained with DAPI (Sigma Aldrich). Coverslips were mounted on glass slides, and immunofluorescence micrographs were obtained at ×400 magnification using a Zeiss Axiovert 200A immunofluorescence microscope coupled to a Cool SNAP HQ camera and a Nikon ECLIPSE E600 confocal microscope, coupled to a Laser Scan System Radiance 2100 camera (Biorad, Hercules, CA).

One- and Two-Dimensional Electrophoresis and Western Blotting

For one-dimensional electrophoresis (1-DE) Western blotting, 30 μg of protein lysates, obtained from primary cell cultures and from renal tissue homogenate as described,5,16 quantified with a Bio-Rad microassay (Hercules, CA), were separated on 10% SDS-PAGE and on NuPage 4 to 12% Bis-Tris pre-cast gels using MOPS SDS running buffer (Invitrogen), with described conditions.5

For two-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE) Western blotting, 50 μg of proteins were loaded onto 7-cm 3–10 NL IPG-strips (GE Health care, Uppsala, Sweden) and then separated on NuPage 4% to 12% pre-cast gels. 1-DE and 2-DE gels were blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes that were stained with Ponceau S (Sigma-Aldrich) to check transferred proteins. Membranes were incubated for two hours with rabbit polyclonal antibodies against-AnxA3 (1.25 μg/ml; ab33068, Abcam) and against β-actin (dilution 1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich) and mAb against HIF-1α (dilution 1:500, clone 54, BD Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, KY). The detection was performed by one-hour incubation at room temperature with secondary antibodies coupled with horseradish peroxidase and SuperSignal West Dura Detection System (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Densitometric analysis was performed using a GS-710 imaging densitometer equipped with Quantity One Software (Bio-Rad). For Mass Spectrometry analysis, 200 μg of cortex culture lysate was separated on 2-DE and blotted on membrane as described above. The gel and membrane were stained with SYPRO® Ruby Protein Gel Stain (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen). The immunoreactivity of AnxA3 was found on the membrane with the specific antibody, and the image was matched with corresponding images of gel and membrane stained by SYPRO using Image Scanner and Image Master 2D Platinum (GeneBio, Geneve, CH). The protein spot corresponding to the most intense signal evidenced by anti-AnxA3 antibody on 2-DE Western blot was excised from the 2-DE gel, and MALDI-TOF analysis was performed as previously described.17

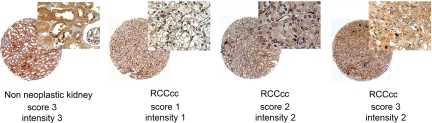

Tissue Microarrays

In 51 of our 60 patients immunohistochemistry analysis of tumor surgical samples on tissue microarray (TMA), prepared as described18 and using rabbit polyclonal antibody against AnxA3 (dilution 1:500), was performed. In 33 of these 51 patients the normal cortex surgical samples were available for immunohistochemistry analysis. Antigen-antibody detection was performed with an anti-rabbit peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and revealed using the DAKO ChemMate EnVision Detection kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Immunostained slides were evaluated independently using light microscopy by two observers in a blind study. To grade the results of staining in each single case, the percentage of positive cells was scored as: 0 = no positive cells, 1 = < 10%, 2 = 10% to 50%, 3 = 50% to 75%, 4 = > 75%. The intensity of AnxA3 immunoreactivity was scored as: 1 = weak, 2 = moderate, 3 = intense. By multiplying the score with the intensity19 we obtained the final score of normal and tumor tissue for each case (range, 1 to 9).

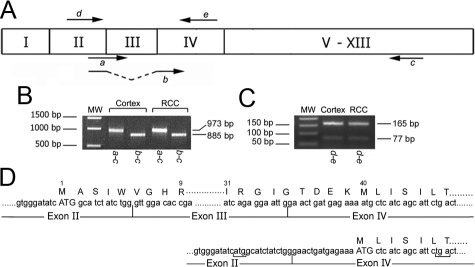

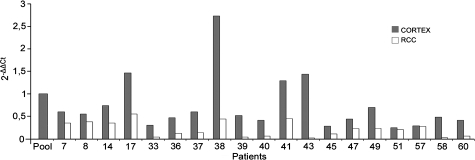

RT-PCR and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was obtained from primary cultures by TRIZOL extraction (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), treated by DNase, spectrophotometrically quantified, and analyzed on 1% agarose gel. 8 μg of RNA were reverse transcribed in a 40 μl reaction in presence of 0.5 μg of random hexamers.20 2.5 μl of cDNA were amplified in the presence of 0.4 μmol/L primers and 2× AmpliTaq Gold PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in a 50 μl reaction, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The amplification program with primers a–c was 95°C/5 minutes, (95°C/35 s, 58°C/35 s, 72°C/1 minute 30 s) × 40 cycles, 72°C/7 minutes (expected amplicon of 973 bp); with primers b–c was 95°C/5 minutes, (95°C/35 s, 60°C/35 s, 72°C/1 minute 30 s) × 10 cycles, (95°C/35 s, 58°C/35 s, 72°C/1 minute 30 s) × 30 cycles, 72°C/7 minutes (expected amplicon of 885 bp); with primers d–e was 95°C/5 minutes, (95°C/35 s, 58°C/35 s, 72°C/35 s) × 43 cycles, 72°C/7 minutes (expected amplicons of 165 bp and 77 bp). 20 μl of these amplification reaction products were run on 1.2% or 2.5% agarose gel. All PCR products obtained in different amplification reactions were sequenced. The primers used, tested for specificity, had the following sequences and localizations: a) 5′-ATGGCA TCTATCTGGgttgg-3′ forward (exon II–III); b) 5′-ATGGCATCTATCTGGgaactga-3′ forward (exon II–IV); c) 5′-ttcagtcatctccaccacaga-3′ reverse (exon XII); d) 5′-TCAAGGCAAAGGTGGGATATCATG-3′ forward (exon II); e) 5′-CCTCTCAGTCAGAATGCTGATGAG3′ reverse (exon IV). Primers a, b, and d encompass the START codon, and primer c encompasses the STOP codon. The capital and lower case letters of primers a and b show the fusion point of the sequences belonging to different exons. TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was carried out, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with commercial kit Hs00192983_m1, which, containing forward and reverse primers located respectively on exon III and IV and a probe spanning exon III-IV, is specific for quantification of AnxA3 transcript containing exon III. GAPDH transcript quantification, as endogenous control of RNA quality, was performed with Hs99998805_m1 kit. The amplifications were carried out in 20 μl reactions containing 100 ng of cDNA, 1X Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and corresponding primers and probes in an ABI PRISM® 7900HT Sequence Detector System (Applied Byosystems), in duplicate for each sample. The relative levels of AnxA3 transcript were expressed as 2−ΔΔCt, representing the expression fold respect to a calibrator5 considered to be equal to 1. A pool of all normal cortex primary culture cDNA was chosen as the calibrator.

Statistical Analysis

Comparison among different experimental groups was performed using Student t test, paired t test, or Kruskal–Wallis test. A value P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. If not otherwise indicated, data were expressed as mean ± SE.

Results

Primary Culture Characterization

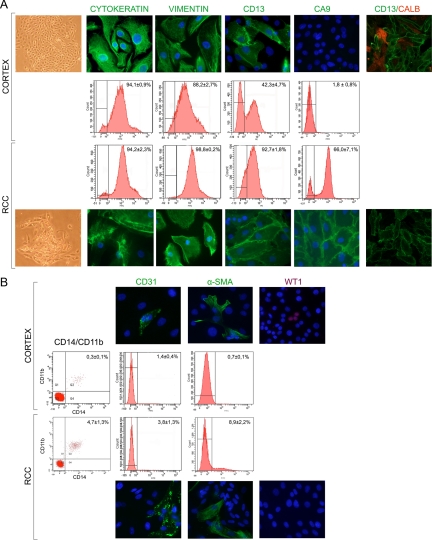

Primary cultures were established from surgical specimens of 60 RCC patients whose clinical characteristics are reported in Table 1B. Primary cultures from RCC tissues and from normal cortex tissues were obtained with an efficiency, respectively, of 73% and 93%. The efficiency in establishing primary cultures from RCC-cortex matched samples was 72% (38 matched cultures of 54 matched samples). The mean doubling time within the second through fourth passage for RCC cultures was 75 hours (range, 48 to 99 hours) with a higher rate of dying cells, evaluated by FACS (data not shown), respect to the normal cultures in which the doubling time was 27 hours (range, 21 to 35 hours). The RCC and normal cortex primary cultures easily reach 3 to 4 passages, then the growth rate slows down until the seventh passage beyond which they continue their growth with difficulty. The cultured normal cells show a characteristic homogeneous epithelial morphology and a more heterogeneous epithelioid morphology with neoplastic foci in the case of tumor cells (Figure 1A). The cellular composition of our primary cultures was routinely analyzed. Cytokeratin, an epithelial marker, was expressed in about 94% of cells both in cortex and RCC cultures. About 88% of the cells in cortex and 99% in RCC cultures were positive for vimentin (Figure 1A), a mesenchymal marker known to be expressed by tubular cells during in vitro growth21 and by RCC cells both in vivo and in vitro.5 One third of our cultures have been also characterized with other markers. CD13, an antigen specific of the proximal brush border,22 was positive in about 43% of cells in cortex cultures. The calcium binding protein calbindin, which is localized in the kidney exclusively in the distal tubule and in the proximal part of the collecting ducts,23 did not coexpress with CD13 in normal cortex cultures; in fact, CD13-negative cells were calbindin-positive and vice versa (Figure 1A). Thus, our cortex cultures are composed of epithelial cells of both proximal and distal tubule origin. In RCC cultures, instead, about 93% of cells were CD13-positive and did not evidence any detectable signal for calbindin (Figure 1A), in accord with the proximal tubular origin of RCCcc and RCCpap.24 Moreover, primary cultures were analyzed for the expression of CA9, a powerful marker for RCC, which is known to be expressed in most, although not all, of the malignant clear cells, in a smaller number of papillary cells and is almost undetectable in normal renal cells.25,26 Our tested RCC cultures were positive for CA9, and the FACS analysis showed that in RCC cultures an average of about 66% of cells were CA9-positive, whereas less than 2% of cells were positive in normal cortex cultures (Figure 1A). These data proved the normal and neoplastic phenotype of our primary cultures that has been confirmed also by the genomic analysis of some of these cultures (Cifola et al, manuscript in preparation). In our cultures the endothelial contamination, assessed by CD31 expression, was about 1% and 4% in cortex and RCC cultures, respectively (Figure 1B). Similarly, the podocyte contamination, evaluated by immunofluorescence analysis of the podocyte lineage marker WT-1,27 was very low (about 1%) in normal cortex cultures and undetectable in RCC cultures (Figure 1B). The monocytic/macrophagic contamination evaluated by CD14 and CD11b expression was negligible (about 0.3%) in normal cortex cultures and around 4% in RCC cultures. Fibroblastic contamination was evaluated analyzing the expression of α-SMA, a mesenchymal cytoskeletric marker that in human kidney may also be expressed by activated fibroblast and tubular cells undergoing the process of epithelial-mesenchymal transition.28,29,30 α-SMA–positive cells in cortex cultures were less than 1%, and this value increased to about 9% in RCC cultures. The coexpression of α-SMA and cytokeratin in our cultures (data not shown) suggests an epithelial origin of most of cells. No significant differences were found between clear cell and papillary RCC cultures. Thus, all these data show that the nonepithelial cell contamination of our cultures is indeed very low.

Figure 1.

Phenotypic characterization of normal cortex and RCC primary cultures. A: Representative micrographs of contrast phase morphology (×40 magnification) and of immunofluorescence staining (×400 magnification) of indicated markers in normal cortex (top panels) and RCC primary cultures (bottom panels). The coexpression of CD13 (in green) and calbindin (in red) have also been evaluated. Representative FACS analysis (middle panels) for tested markers is also reported. B: Evaluation of nonepithelial cells in normal cortex and RCC primary cultures by immunofluorescence (top and bottom panels) and FACS analysis (middle panels). DAPI counterstains the nuclei in blue. Percentage of positivity, evaluated by FACS analysis, is reported as mean ± SE of several experiments. In the case of CD14/CD11b the mean percentage of coexpression is reported.

Western Blot Analysis of AnxA3 and HIF-1α Protein in Cortex and RCC Primary Cultures

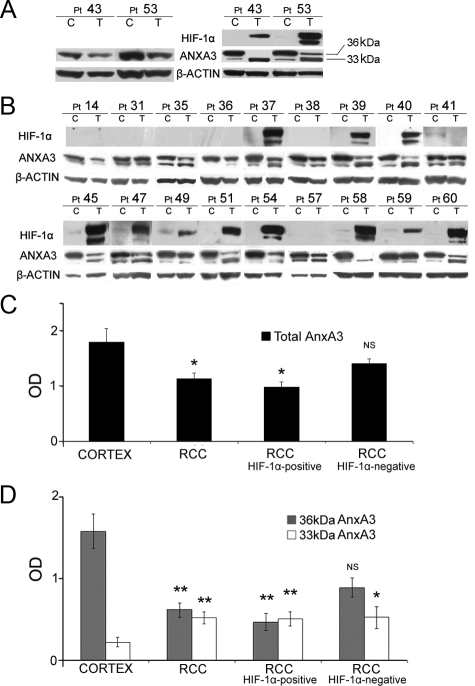

These well characterized cortex and RCC primary cultures have been used to study the expression pattern of AnxA3 gene. When Western blot analysis of matched normal cortex and RCC primary cultures was performed on 10% SDS-PAGE, as often described by others,7,31 the anti-AnxA3 antibodies detected a single protein band (as shown in Figure 2A for samples n. 43 and n. 53). Two reports,12,13 using a one-dimensional 12% SDS-PAGE and Western blot evidenced, respectively, in ischemic rat brain and in HL-60 cells, two AnxA3 bands of 36 and 33 kDa. Based on these data we submitted the available protein lysates of our primary cultures to separation on NuPage 4% to 12% gradient gel. Western blot by anti-AnxA3 antibodies revealed two quite closely migrated bands between the 30- and 40-kDa markers, a slower migrating band, likely the 36-kDa form and a faster migrating one, likely the 33-kDa form, in both normal cortex and RCC lysates of 16 of 20 matched primary cultures (Figure 2, A and B). Two of four remaining matched lysates (n. 43, n. 58) showed only the 33-kDa band in RCCcc cultures and the other two (n. 36, n. 45) only the 36-kDa band in cortex cultures. The total expression of AnxA3 was significantly down-regulated (P = 0.01, Student t test) in RCC cultures respect to cortex cultures (Figure 2C). In the RCC primary culture lysates of the 20 samples analyzed, the 33-kDa protein band was found up-regulated (P < 0.01) and the 36-kDa protein band down-regulated (P < 0.01) compared with matched cortex cultures (Figure 2D). In the 20 matched culture lysates studied also the expression of HIF-1α protein was evaluated (Figure 2, A and B). In normal cortex and in 4 nonclear cell RCC (pt 14, 36, 41, 57) HIF-1α was absent or negligible, as expected, and it was also absent in 3 of 16 (19%) RCCcc primary cultures (pt 31, 35, 38), which represents the expected percentage of RCCcc without the biallelic inactivation of VHL gene.2 A good correlation between HIF-1α expression and defective VHL has been reported in literature.32 The expression pattern of AnxA3 in the 7 RCC lysates of the cultures not expressing HIF-1α (HIF-1α–negative) and in the matched normal cortex lysates was similar, with the 36-kDa band more abundant than the 33-kDa band. In particular, the decrease of total AnxA3 and of 36-kDa band was not significant respect to the normal cortex cultures, instead the increase of the 33-kDa band was significant (P = 0.01; Figure 2, C and D). In the remaining 13 RCCcc expressing HIF-1α (HIF-1α–positive) a further decrement of the total AnxA3 protein and of the 36-kDa band was determined to be significant (P = 0.01 and P < 0.01), whereas the 33-kDa band remained significantly increased (P < 0.01) with respect to the matched cortex cultures (Figure 2, C and D). Thus in these 13 RCC cultures there was an inversion respect to cortex cultures between the quantitative level of 36- and 33-kDa bands, that in nine of these lysates was pronounced and significant (Figure 2D).

Figure 2.

Western blot analysis of AnxA3 and HIF-1α protein pattern in cortex and RCC primary cultures. A: Cell lysates from matched primary cultures established from patients n. 43 and n. 53 run on 10% SDS-PAGE probed with anti-AnxA3 antibodies (left) and run on 4 to 12% gradient gel probed with anti-AnxA3 and anti-HIF-1α antibodies (right). B: AnxA3 and HIF-1α protein pattern in cell lysates of 18 matched primary cultures established from corresponding patients and analyzed by 4% to 12% gradient gel. Anti–β actin immunoblotting assessed loading. C: Densitometric analysis of total AnxA3 bands, normalized for the corresponding β-actin band of 20 cortex, 20 RCC, 13 RCC HIF-1α–positive, 7 RCC HIF-1α negative primary culture lysates. D: Densitometric analysis of the 36-kDa and 33-kDa AnxA3 bands, normalized for the corresponding β-actin band, in the same lysates evaluated in C. Means ± SE. All cultures are from RCCcc patients (Pt) except n. 36, n. 41 RCCpap, and n. 14, n. 57 RCCmixed. C indicates cortex culture; T, RCC culture. *P = 0.01; **P < 0.01; NS indicates not significant respect to the matched normal cortex samples (Student t test).

2-DE Western Blot Analysis of AnxA3 Protein Expression in Cortex and RCC Primary Cultures

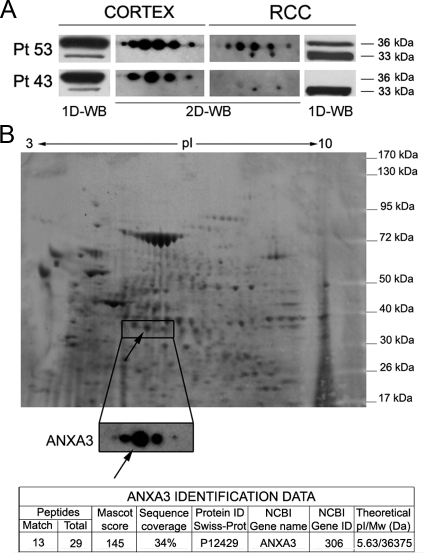

To increase the resolution of the AnxA3 protein pattern and to check whether additional isoforms were detectable and differentially expressed, 2-DE Western blot was performed in two matched pairs of normal cortex and RCC primary cultures (n. 43 and 53). Multiple spots were indeed observed in both normal cortex and RCC. In particular, anti-AnxA3 antibodies detected four to six spots corresponding to 36-kDa isoform in normal cortex and RCC primary culture lysates n. 53 and in cortex but not in RCC primary culture lysate n. 43 in which the 36-kDa band was undetectable by 1-DE Western blot (Figure 3A). Two additional spots likely corresponding to the 33-kDa isoform were detected in RCC primary culture lysates of both cases n. 53 and n.43, whose 33-kDa band in 1-DE Western blot was up-regulated. The largest 36-kDa spot of AnxA3 detected by 2-DE Western blot was identified by MALDI-TOF in a pool of cortex primary cultures established from different patients (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

A: Immunodetection of the AnxA3 isoforms on the 2-DE Western blot (2D-WB) of matched primary cell culture lysates of patients n. 53 and n. 43 and corresponding pattern of isoforms obtained by 1-DE Western blot (1D-WB), after separation on 4% to 12% gradient gel. B: Sypro-stained membrane obtained after 2-DE separation on 4% to 12% gel of a pool of protein lysates from different normal cortex primary cultures. In the enlargement the immunoreactivity of the AnxA3 isoforms on the same membrane is shown. The isoelectric point (pI) and molecular weight markers are reported; the arrows show the specific spot that after gel-excision and MS analysis has been identified as AnxA3 protein.

AnxA3 Protein Expression in Cortex and RCC Tissues

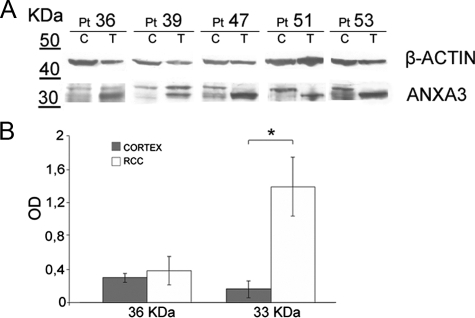

To prove that the expression of the two forms of AnxA3 was not related to the in vitro growth, we analyzed by NuPage 4% to 12% gradient gel and Western blot, on the basis of sample availability, the lysates of five different matched normal cortex and RCC tissues. The two bands were detectable also in tissue samples and in particular the 33-kDa protein band in RCC tissue samples was more intense than the 36-kDa band, which in two cases was undetectable (Figure 4A). In the RCC tissue samples analyzed, the 33-kDa band was found significantly up-regulated (P = 0.01) respect to cortex tissue samples (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis of AnxA3 in cortex and RCC tissues. A: AnxA3 protein pattern in cell lysates of matched normal and tumor tissues obtained from five patients, after separation on 4% to 12% gradient gel. Anti–β actin immunoblotting assessed loading. B: Densitometric analysis of 36-kDa and 33-kDa AnxA3 bands, normalized for corresponding β-actin band. Means ± SE of the five matched tissues analyzed. All patients (Pt) are RCCcc except n. 36 RCCpap. C indicates cortex tissue; T, RCC tissue. *P = 0.01, Student t test.

The individual variability in AnxA3 expression level determined in RCC was confirmed by TMA analysis in 51 of our 60 RCC surgical samples, and AnxA3 staining detected both in the nucleus and cytoplasm of RCC cells (Figure 5) varied among the different patients, but the final score was low (<4) in 80% of RCC samples (Table 2). In 33 of 51 RCC cases the matched normal cortex tissue was available for immunohistochemistry analysis and showed a diffuse and high intensity staining for AnxA3 both in tubules and glomeruli (Figure 5). In 29 (88%) of these matched cases the AnxA3 staining final score in normal cortex tissue was significantly higher (P < 0.01, paired t test) than in corresponding RCC tissues and in the remaining four cases the final score of normal and tumor tissue was the same (Table 2). In RCC tissues no significant correlations between final score distribution and clinical-pathological data were observed.

Figure 5.

Selected images of tissue microarray analysis performed on histopathological samples of 51 RCC and 33 matched non-neoplastic kidney tissues. AnxA3 immunoreactivity with corresponding score and intensity values. Original magnifications: ×40 and ×400 (insets).

Table 2.

AnxA3 Immunoreactivity Evaluated by TMA in Tumor and Normal Cortex and Analysis of Clinical-Pathological Correlation

| Variables | TMA tumor

|

TMA normal cortex

|

Final score TMA ratio† | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 1

|

2

|

3

|

P* | n | 2

|

3

|

||||||||||

| Score Intensity final score | 1 1 n (%) | 2 2 n (%) | 1 2 n (%) | 2 4 n (%) | 1 3 n (%) | 2 6 n (%) | Score Intensity final score | 2 4 n (%) | 3 6 n (%) | 2 6 n (%) | 3 9 n (%) | <1‡ n (%) | =1 n (%) | ||||

| Sex | |||||||||||||||||

| Male | 34 | 13 (38) | 3 (9) | 9 (26) | 3 (9) | 3 (9) | 3 (9) | NS | 21 | 1 (5) | 7 (33) | 2 (9) | 11 (53) | 19 (90) | 2 (10) | ||

| Female | 17 | 4 (24) | 3 (17) | 4 (24) | 1 (6) | 2 (12) | 3 (17) | 12 | 1 (8) | 4 (33) | 0 (0) | 7 (59) | 10 (83) | 2 (17) | |||

| Age, y | |||||||||||||||||

| <40 | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | NS | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | ||

| 41 to 50 | 6 | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 2 (33) | 3 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | 0 (0) | 3 (75) | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| 51 to 60 | 19 | 6 (32) | 4 (21) | 6 (32) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 1 (5) | 15 | 0 (0) | 4 (27) | 2 (13) | 9 (60) | 15 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| 61 to 70 | 16 | 7 (44) | 1 (6) | 3 (19) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 4 (25) | 8 | 0 (0) | 6 (75) | 0 (0) | 2 (25) | 4 (50) | 4 (50) | |||

| >71 | 9 | 3 (34) | 1 (11) | 2 (22) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | 1 (11) | 5 | 2 (40) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (60) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | |||

| Histological type | |||||||||||||||||

| RCCcc | 48 | 16 (33) | 5 (11) | 13 (27) | 3 (6) | 5 (11) | 6 (12) | NS | 27 (87) | 4 (13) | |||||||

| RCCpap | 2 | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | ||||||||

| RCCmixccpap | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | ||||||||

| Tumor grade | |||||||||||||||||

| G1 | 3 | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (33) | 1 (34) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NS | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | |||||||

| G2 | 39 | 12 (31) | 6 (15) | 10 (25) | 3 (8) | 3 (8) | 5 (13) | 25 (89) | 3 (11) | ||||||||

| G3 | 9 | 4 (44) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | 0 (0) | 2 (22) | 1 (12) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | ||||||||

| Tumor stage | |||||||||||||||||

| pT1 | 34 | 13 (38) | 3 (9) | 8 (23) | 2 (6) | 5 (15) | 3 (9) | NS | 21 (91) | 2 (9) | |||||||

| pT2 | 7 | 2 (28) | 0 (0) | 2 (29) | 1 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 (29) | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | ||||||||

| pT3 | 10 | 2 (20) | 3 (30) | 3 (30) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 5 (83) | 1 (17) | ||||||||

Kruskal-Wallis test. NS indicates not significant.

Ratio between matched tumor and normal cortex final score (score × intensity) of each single case.

The “paired t test” between matched tumor and normal cortex final score demonstrated a significant decrement (P < 0.01) of AnxA3 in tumor tissue.

Analysis of AnxA3 Transcripts in Cortex and RCC Primary Cultures

To investigate whether the two AnxA3 isoforms may originate from alternative splicing events we studied the specific mRNA obtained from different cortex and RCC primary cultures by RT-PCR, using different set of primer (Figure 6A). The different cDNA amplified in presence of primers a–c provide a single full-length coding sequence band of expected 973 bp. The primers b–c were able to amplify in the same cDNA a single shorter band of 885 bp that lacks only exon III (Figure 6B). The amplification of cDNA with primer d–e provides two bands of 165 and 77 bp (Figure 6C). All amplicons obtained were sequenced and the sequence of the larger amplicons contained the coding sequence for a protein of 323 amino acids corresponding to the 36-kDa isoform, whereas the shorter bands arise by alternative splicing of exon III. The lack of this exon breaks the open reading frame and the translation of the spliced transcript is possible only if a downstream ATG codon corresponding to the first methionine in exon IV is used (Figure 6D); consequently the first 39 amino acids are lost, and the resulting protein of 284 amino acids accounts for the 33-kDa protein isoform. The expression level of the longer AnxA3 mRNA has also been quantified by real-time PCR in 19 matched normal cortex and RCC cultures (Figure 7). The longer AnxA3 transcript was less abundant in RCC than in corresponding cortex primary cultures in all samples analyzed. This expression difference, analyzed comparing ΔΔCT values by “paired t test,” was statistically significant (P = 0.01), and the decrement was more significant in HIF-1α–positive cultures. The heterogeneity in AnxA3 longer transcript expression levels among different patients reflects an interindividual variability and do not correlate with the patient’s clinical data. No commercial kits are available for the quantification of shorter AnxA3 transcript, and our attempts to produce a functional quantification test were unsuccessful.

Figure 6.

Detection of two AnxA3 transcripts in cortex and RCC primary cultures by RT-PCR analysis. A: Schematic representation of the exon structure of the AnxA3 gene. The localizations of the specific forward and reverse primers used in the PCR assays are indicated by arrows. Primer b spans noncontiguous sequences belonging to different exons. B: The a–c primer pair amplified a band of 973 bp of AnxA3 encompassing the full-length coding sequence containing exon III in both cortex and RCC cDNA samples. The b–c primer pair amplified in the same cDNA samples a band of 885 bp corresponding to the full-length coding sequence of AnxA3 lacking exon III. C: The d--e primer pair amplified in cortex and RCC cDNA samples, two bands of 165 and 77 bp corresponding to the AnxA3 transcripts respectively encompassing and lacking exon III. D (top): Partial nucleotide sequence of the AnxA3 transcript isoform containing exon III, the corresponding amino acid sequence that starts with ATG in exon II is enumerated; bottom: Partial sequence of the AnxA3 isoform lacking exon III. The translation of this spliced transcript starts from the “ATG” coding for the first methionine in exon IV (M40 of the unspliced isoform). The tga stop codon (underlined) raised in exon IV by the frame shift attributable to the spliced event, when the atg start codon (underlined) in exon II is used, is shown.

Figure 7.

Relative quantification by real-time PCR of AnxA3 transcript containing exon III in 19 matched normal cortex and RCC cultures obtained from corresponding patients. The value expressed as 2−ΔΔCt represent the fold of transcript expression respect to a pool of all normal cortex cDNA samples, used as calibrator with a value of 1. Each sample has been analyzed in duplicate. All patients are RCCcc except n. 36, n. 41 RCCpap and n. 14, n. 57 RCCmixed.

Discussion

We established primary cell cultures from normal cortex and RCC tissue samples with high efficiency and reproducibility. The rate of success in establishing primary cultures was not correlated with clinical-pathological characteristics of neoplastic patients. The growth rate and survival data of our cultures were in agreement with those described by others33,34 and indicated that RCC cultures have a longer doubling time attributable to differences in cell loss, and probably in growth fraction and in length of cell cycle time as we can hypothesize from literature data.35,36,37 FACS and immunofluorescence demonstrated that our cortex cultures were essentially composed of epithelial tubular cells of proximal and distal origin, whereas RCC cultures were composed of neoplastic cells derived from proximal tubule cells. In both normal cortex and RCC cultures the fibroblastic, podocytic, endothelial, and monocytic/macrophagic contaminations were quite low and granulocytes, that remain in suspension, were absent in our adherent cultures. The expression of vimentin and α-SMA in cytokeratin-positive normal tubular epithelial cells and tumor cells may have been induced by culture on plastic21 and the further increment of α-SMA in RCC cultures may have been attributable to phenotypic changes characteristic of epithelial-mesenchymal transition occurring in the neoplastic tubular cells.30 This well characterized in vitro model proved to be useful for studying the molecular differences between normal tubular cells and their neoplastic counterpart. In particular, these primary cultures have been instrumental for the molecular characterization of AnxA3 expression, performed for the first time in cortex and RCC cells. Recently, studies dealing with the prognostic relevance of AnxA3 gene product in lung cancer,7 and in prostate cancer8 in which it is down-expressed, and in colorectal human cancer9 in which it is over-expressed without prognostic relevance, raised our interest. Furthermore, unlike other members of the annexin family,38,39 for AnxA3 there are no extensive studies in kidney and RCC. Our Western blot analysis shows that AnxA3 proteins are, on the whole, more abundant in cells of cortex cultures than RCC cultures. The Western blot data on tissues of a few cases seem to be discordant but it must be underlined that the cellular composition of normal and tumor renal tissue is much more heterogeneous than primary cultures, in particular there may be a variable presence of inflammatory phagocytes in RCC tissue. Moreover, the TMA analysis shows that in the normal tissue AnxA3 is consistently well expressed, whereas in RCC sections its expression is variable but significantly lower than in corresponding matched normal cortex sections, without any correlation to clinical-pathological data. Otherwise, AnxA3 has been found to be down-regulated also in prostate cancer, in which a heterogeneous expression has been described by TMA analysis.40 The down-regulation of AnxA3 in prostate cancer has been suggested to occur in a context of autoimmunity that, however, cannot be invoked in our in vitro model. In our study, two protein bands of AnxA3 were detected in primary cell culture lysates of both normal cortex and RCC. One of 36 kDa was more abundant in cortex cells as confirmed also by real-time PCR at transcript level, and one of 33 kDa was more abundant in tumor cells. Even the 2-DE Western blot analysis of primary culture lysates evidenced several spots, like those described in rat brain after cerebral ischemia,13 corresponding to 36-kDa and 33-kDa bands of AnxA3. Until now the expression of two isoforms of AnxA3 of 36 and 33 kDa has been documented only in human monocytes and neutrophils12 and in rat brain, where the up-regulation of the 33-kDa AnxA3 isoform after stroke has been correlated to the inflammatory phagocytic infiltration in the damaged area.13 The extensive phenotypic characterization of our cell cultures has documented only a negligible contamination by monocytic/macrophagic cells. Neutrophils were absent in our adherent cultures. Therefore, this study demonstrates, for the first time, that the presence of two AnxA3 isoforms is characteristic also of normal and tumor renal cells. The two band pattern of AnxA3 has been also observed in normal cortex and RCC tissues and our in vitro model, retaining the same phenotype of the original tissue, proves again to be reliable.

Le Cabec et al have already shown that the 36-kDa isoform detected in monocytes did not account for post-translational modifications, like phosphorylation or glycosylation, of the 33-kDa isoform.12 Moreover, the origin of different isoforms has been explained for other members of annexin family by transcript alternative splicing events, as described also in kidney cells.41 Our data document an alternative splicing of exon III that, causing the loss of 39 amino acids, accounts for the molecular weight difference of the two AnxA3 protein isoforms. In fact, the translation of the 33-kDa protein is possible only if a downstream start codon corresponding to the first methionine in exon IV is used; such a mechanism has been reported also for other proteins involved in the HIF pathway.42 Some years ago a report suggested for AnxA3 a role in the enhancement of the transactivating activity of HIF-1.11 Our data also suggest a complex relationship between AnxA3 and HIF-1. In addition, our data might indicate a molecular interpretation of the different prognosis of RCCcc patients with VHL−/− and VHL wild type (wt). The N-terminal domain of AnxA3 with its tryptophan 5 (W5) residue is known to be involved in the modulation of membrane binding and nonspecific cationic permeability.43 If W5 is mutated or lost, as in the 33-kDa isoform, the interaction of the protein with membrane is modified and cellular calcium-influx is increased. We could postulate that in RCC the increased level of 33-kDa AnxA3 isoform but also the reciprocal ratio of the two isoforms might be important in the regulation of cellular calcium-influx. Interestingly, it has been recently shown44 that among the direct targets of the transactivating activity of HIF-1α protein there is also the S100A4 protein, known to interact with proteins involved in cytoskeleton rearrangement and cell motility in a calcium-dependent manner.45 These aspects might be related with the more severe prognosis of VHL−/− RCCcc (HIF-1α positive) patients.3 In the HIF-1α negative RCC cells (likely VHL wt), in which the 36-kDa form is more abundant, a limited calcium-influx in absence of a HIF-1α–dependent increase of S100A4 level might contribute to a less aggressive RCC phenotype. Otherwise, the increment in HIF-1α–positive RCCcc cells of 33 kDa protein respect to normal cortex but also respect to the 36-kDa isoform mimics the behavior of inflammatory phagocytes in brain after stroke,13 although in these leukocytes HIF protein level is likely to be low because VHL gene is not inactivated and also the intracellular oxygen level is high because of “respiratory burst.” Even in this case, the 33-kDa isoform increment and the consequent increase of intracellular calcium level might have a role in the control of leukocyte motility. One must also consider that the AnxA3-dependent modulation of membrane cationic permeability might have a role, through Ras/Raf pathways, in regulating HIF-1α protein stability46 and thus in enhancing the transactivating activity of HIF-1 evidenced by others.11 Besides, this additional pathway of HIF stability might also be involved in maintaining the same morphological phenotype in VHL−/− RCCcc and VHL wt RCCcc. Furthermore, our data show that the global reduction of AnxA3 level in RCC is related to the sole decrease of 36-kDa form. We cannot explain why this decrement takes place, but it must be remembered that another member of Annexin family, the AnxA1 protein, is able to increase its own expression47 with its characteristic N-terminus. The unique N-terminus of 36-kDa AnxA3 form6,43 is lost in the 33-kDa form, and this may have a role on the regulation of the whole AnxA3 expression. Only an improvement in the molecular and functional knowledge of AnxA3 isoforms might give insight in their potential clinical utility, even if there already are promising perspectives to investigate a possible use of AnxA3 as a biomarker. In fact, recently it has been demonstrated that AnxA3 can be quantified in urine of prostate cancer patients,48 that it is present in urinary exosomes deriving from different renal cell types,49 and exosomes may be separated from serum as well.50 These data increase the likelihood of detecting a specific AnxA3 protein pattern in urine and/or blood samples and make its evaluation for clinical management of RCC patients more feasible.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Matteo Corizzato for computational and statistical analysis, Dr. Roberta Rigolio for help in the FACS analysis, Dr. Ester Fasoli for immunohistochemistry analysis, and Dr. Rosanna Falbo for revision of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Prof. Roberto A. Perego, Department of Experimental Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Milano-Bicocca, Via Cadore 48, 20052 Monza, Italy. E-mail: roberto.perego@unimib.it.

Supported by grants from Italian Ministry for Research: COFIN 2001 (n. 58539), FIRB 2001 (n. RBNE01HCKF), PRIN 2004 (n. 61903_004), PRIN 2006 (n. 69373_004), FIRB 2007 (n. RBRN07BMCT). Work in the laboratories of S.B., V.A., L.I., and V.D.S. was supported by MIUR grants for Ph.D. program.

C.B. and S.B. contributed equally to this work.

References

- Cohen HT, McGovern FJ. Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2477–2490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beroukhim R, Brunet JP, Di Napoli A, Mertz KD, Seeley A, Pires MM, Linhart D, Worrell RA, Moch H, Rubin MA, Sellers WR, Meyerson M, Linehan WM, Kaelin JG, Signoretti S. Patterns of gene expression and copy-number alterations in von-Hippel Lindau disease-associated and sporadic clear cell carcinoma of the kidney. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4674–4681. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaelin WG., Jr The von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor protein: O2 sensing and cancer. Nat Rev Canc. 2008;8:865–873. doi: 10.1038/nrc2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglard P, Trahan E, Liu S, Latif F, Merino MJ, Lerman MI, Zbar B, Linehan WM. Molecular and cellular characterization of human renal cell carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 1992;52:348–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perego RA, Bianchi C, Corizzato M, Eroini B, Torsello B, Valsecchi C, Di Fonzio A, Cordani N, Favini P, Ferrero S, Pitto M, Sarto C, Magni F, Rocco F, Mocarelli P. Primary cell cultures arising from normal kidney and renal cell carcinoma retain the proteomic profile of corresponding tissues. J Prot Res. 2005;4:1503–1510. doi: 10.1021/pr050002o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerke V, Creutz CE, Moss SE. Annexins: linking Ca2+ signaling to membrane dynamics. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:449–461. doi: 10.1038/nrm1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YF, Xiao ZQ, Li MX, Li MY, Zhang PF, Li C, Li F, Chen YH, Yi H, Yao HX, Chen Z-C. Quantitative proteome analysis reveals annexin A3 ad a novel biomarker in lung adenocarcinoma. J Pathol. 2008;217:54–64. doi: 10.1002/path.2429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollermann J, Schlomm T, Bang H, Schwall GP, von Eichel-Streiber C, Simon R, Schostak, Huland H, Berg W, Sauter G, Klocker H, Schrattenholz Expression and prognostic relevance of Annexin A3 in prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2008;54:1314–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madoz-Gúrpide J, López-Serra P, Martínez-Torrecuadrada JL, Sánchez L, Lombardía L, Casal JI. Proteomics-based validation of genomic data. Molec Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:1471–1483. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600048-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shekouh AR, Thompson CC, Prime W, Campbell F, Hamlett J, Herrington CS, Lemoine NR, Crnogorac-Jurcevic T, Buechler MW, Friess H, Neoptolemos JP, Pennington SR, Costello Application of laser capture microdissection combined with two-dimensional electrophoresis for the discovery of differentially regulated proteins in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Proteomics. 2003;3:1988–2001. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park JE, Lee DH, Lee JA, Park SG, Kim NS, Park BC, Cho S. Annexin A3 is a potential angiogenic mediator. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;337:1283–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Cabec V, Russo-Marie F, Maridonneau-Parini I. Differential expression of two forms of Annexin A3 in human neutrophils and monocytes and along their differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;189:1471–1476. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90240-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junker H, Suofu Y, Venz S, Sascau M, Herndon JG, Kessler C, Walther R, Popa-Wagner A. Proteomic identification of an upregulated isoform of Annexin A3 in the rat brain following reversible cerebral ischemia. Glia. 2007;55:1630–1637. doi: 10.1002/glia.20581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seliger B, Dressler SP, Wang E, Kellner R, Recktenwald CV, Lottspeich F, Marincola FM, Baumgärtner M, Atkins D, Lichtenfels R. Combined analysis of transcriptome and proteome data as a tool for the identification of candidate biomarkers in renal cell carcinoma. Proteomics. 2009;6:1567–1581. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trojaneck B, Niemitz S, Micka B, Lefterova P, Blasczyk R, Scheffold C, Huhn D, Schmidt-Wolf IGH. Establishment and characterization of colon carcinoma and renal cell carcinoma primary culture. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2000;15:169–174. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2000.15.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raimondo F, Ticozzi-Valerio D, Magni F, Perego R, Bianchi C, Sarto C, Casellato S, Fasoli E, Ferrero S, Cifola I, Rocco F, Kienle MG, Mocarelli P, Brambilla P, Pitto M. Caveolin-1 and Flotillin-1 differential expression in clinical samples of renal cell carcinoma. The Open Proteomic Journal. 2008;1:87–98. [Google Scholar]

- Magni F, Sarto C, Valsecchi C, Casellato S, Ferrero Bogetto S, Bosari S, Di Fonzo A, Perego RA, Corizzato M, Doro G, Galbusera C, Rocco F, Mocarelli P, Galli Kienle M. Expanding the proteome two-dimensional gel electrophoresis reference map of human renal cortex by peptide mass fingerprinting. Proteomics. 2005;5:816–825. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberis M, Pellegrini C, Cannone M, Arizzi C, Coggi G, Bosari S. Quantitative PCR and HER2 testing in breast cancer: a technical and cost-effectiveness analysis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:563–570. doi: 10.1309/1AKQDQ057PQT9AKX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero S, Falleni M, Cattaneo M, Malferrari G, Canton C, Biagiotti L, Maggioni M, Nosotti M, Coggi G, Bosari S, Biunno I. SEL1L expression in non-small cell lung cancer. Hum Path. 2006;37:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perego RA, Bianchi C, Brando B, Urbano M, Del Monte U. Increment of nonreceptor tyrosine kinase Arg RNA as evaluated by semiquantitative RT-PCR in granulocyte and macrophage-like differentiation of HL-60 cells. Exp Cell Res. 1998;245:146–154. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forino M, Torregrossa R, Ceol M, Murer L, Della Vella M, Del Prete D, D'Angelo A, Anglani F. TGFβ1 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition, but not myofibroblast transdifferentiation of human kidney tubular epithelial cells in primary culture. Int J Exp Path. 2006;87:197–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2006.00479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer PC, Nockher WA, Haase W, Scherberich JE. Isolation of proximal and distal tubule cells from human kidney by immunomagnetic separation. Kidney Int. 1997;52:1321–1331. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmingsen C. Regulation of renal calbindin-D28K. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;87:5–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen SS, Krishna B, Chirala R, Amato RJ, Truong LD. Kidney-specific cadherin, a specific marker for the distal portion of the nephron and related renal neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:933–940. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Cuilleron M, Cottier M, Gentil-Perret A, Lambert C, Genin C, Tostain J. the use of MN/CA9 gene expression in identifying malignant solid renal tumors. Eur Urol. 2006;49:401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Passebosc-Faure K, Lambert C, Gentil-Perret A, Blanc F, Oosterwijk E, Mosnier JF, Genin C, Tostain J. The expression of G250/MN/CA9 antigen by flow cytometry: its possible implication for detection of micrometastatic renal cancer cells. Clin Canc Res. 2001;7:89–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud JLR, Kennedy CRJ. The podocyte in health and disease: insights from the mouse. Clinical Science. 2007;112:325–335. doi: 10.1042/CS20060143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strutz F, Zeisberg M. Renal fibloblasts and myofibroblasts in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2992–2998. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thedieck C, Kalbacher H, Kuczyk M, Muller GA, Muller CA, Klein G. Cadherin-9 is a novel cell surface marker for the heterogeneous pool of renal fibroblasts. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e657. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiery JP, Sleeman JP. Complex networks orchestrate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:131–141. doi: 10.1038/nrm1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harashima M, Harada K, Ito Y, Hyuga M, Seki T, Ariga T, Yamaguchi T, Niimi S. Annexin A3 expression increases in hepatocytes and is regulated by hepatocyte growth factor in rat liver regeneration. J Biochem. 2008;143:537–545. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner KJ, Moore JW, Jones A, Taylor CF, Cuthbert-Heavens D, Han C, Leek RD, Gatter KC, Maxwell PH, Ratcliffe PJ, Cranston D, Harris AL. Expression of hypoxia-inducible factors in human renal cancer: ralationship to angiogenesis and to the von Hippel–Lindau gene mutation. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2957–2961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detrisac CJ, Sens MA, Garvin J, Spicer SS, Sense DA. Tissue culture of human kidney epithelial cells of proximal tubule origin. Kidney Int. 1984;25:383–390. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Zhai Y, Chang W, Hou J, He S, Lin L, Yu Y, Xu D, Xiao J, Ma L, Wang G, Cao T, Cao G. Global analysis of metastasis-associated gene expression in primary cultures from clinical specimens of clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:1080–1088. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baserga R. The cell cycle. N Engl J Med. 1981;304:453–459. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198102193040803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JV. Tumor growth dynamics. Br Med Bull. 1991;47:47–63. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a072461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli L, Torricelli A, Ubezio P, Basse B. Modelling the balance quiescence and cell death in normal and tumor cell populations. Math Biosci. 2006;202:349–370. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unwin RD, Craven RA, Harnden P, Hanrahan S, Totty N, Knowles M, Eardley I, Selby PJ, Banks RE. Proteomic changes in renal cancer and co-ordinate demonstration of both the glycolytic and mitochondrial aspects of the Warburg effect. Proteomics. 2003;3:1620–1632. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven RA, Stanley AJ, Hanrahan S, Dods J, Unwin R, Totty N, Harden P, Eardley I, Selby PJ, Banks RE. Proteomic analysis of primary cell lines identifies protein changes present in renal cell carcinoma. Proteomics. 2006;6:2853–2864. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200500549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozny W, Schroer K, Schwall GP, Poznanovic S, Stegmann W, Dietz K, Rogatsch H, Schaefer G, Huebl H, Klocker H, Schrattenholz A, Cahill MA. Differential radioactive quantification of protein abundance ratios between benign and malignant prostate tissue: cancer association of annexin A3. Proteomics. 2007;7:313–322. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200600646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markoff A, Gerke V. Expression and functions of annexins in the kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;289:F949–F956. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00089.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minchenko OH, Ogura T, Opentanova IL, Minchenko DO, Esumi H. Slice isoform of 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase-4: expression and hypoxic regulation. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005;280:227–234. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-8009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann A, Raguenes-Nicol C, Favier-Perron B, Mesonero J, Huber R, Russo-Marie F, Lewit-Bentley A. The annexin A3 membrane interaction is modulated by an N-terminal tryptophan. Biochem. 2000;39:7712–7721. doi: 10.1021/bi992359+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao SH, Zhao XY, Han YH, Zhang J, Wang LS, Xia L, Zhao KW, Zheng Y, Guo M, Chen GQ. Proteomics-based identification of two novel direct targets of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and their potential roles in migration/invasion of cancer cells. Proteomics. 2009;9:3901–3912. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett SC, Varney KM, Weber DJ, Bresnick AR. S100A4, a mediator of metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:677–680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denko NC. Hypoxia. HIF1 and glucose metabolism in the solid tumor. Nature Rev Cancer. 2008;8:705–713. doi: 10.1038/nrc2468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescher U, Danielczyk A, Markoff A, Gerke V. Functional activation of the formil peptide receptor by a new endogenous ligand in human lung A549 cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:1500–1504. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schostak M, Schwall GP, Poznanovic S, Groebe K, Muller M, Messinger D, Miller K, Krause H, Pelzer A, Horninger W, Klocker H, Hennenlotter J, Feyerabend S, Stenzl A, Schrattenholz A. Annexin A3 in urine: a highly specific noninvasive marker for prastate cancer early detection. J Urol. 2009;181:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.08.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisitkun T, Shen R, Knepper MA. Identification and proteomic profiling of exosomes in human urine. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:13368–13373. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawari F, Rohuani FN, Cui X, Yu ZX, Buckley C, Kaler M, Levin SJ. Release of full-lenght 55kDa TNF receptor 1 in exosome-like vesicles: a mechanism for generation of soluble cytokine receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:1297–1302. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307981100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]