Abstract

The novel pandemic influenza H1N1 (H1N1pdm) virus of swine origin causes mild disease but occasionally leads to acute respiratory distress syndrome and death. It is important to understand the pathogenesis of this new disease in humans. We compared the virus tropism and host-responses elicited by pandemic H1N1pdm and seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses in ex vivo cultures of human conjunctiva, nasopharynx, bronchus, and lung, as well as in vitro cultures of human nasopharyngeal, bronchial, and alveolar epithelial cells. We found comparable replication and host-responses in seasonal and pandemic H1N1 viruses. However, pandemic H1N1pdm virus differs from seasonal H1N1 influenza virus in its ability to replicate in human conjunctiva, suggesting subtle differences in its receptor-binding profile and highlighting the potential role of the conjunctiva as an additional route of infection with H1N1pdm. A greater viral replication competence in bronchial epithelium at 33°C may also contribute to the slight increase in virulence of the pandemic influenza virus. In contrast with highly pathogenic influenza H5N1 virus, pandemic H1N1pdm does not differ from seasonal influenza virus in its intrinsic capacity for cytokine dysregulation. Collectively, these results suggest that pandemic H1N1pdm virus differs in modest but subtle ways from seasonal H1N1 virus in its intrinsic virulence for humans, which is in accord with the epidemiology of the pandemic to date. These findings are therefore relevant for understanding transmission and therapy.

The recent pandemic caused by a novel H1N1 virus (H1N1pdm) arose from the reassortment of three or more viruses of swine origin, including the North American triple reassortant H3N2 and H1N2 viruses, classical swine H1N1, and European swine H1N1/H3N2 viruses.1,2 Most patients with pandemic H1N1pdm have mild influenza-like illness, but a minority of patients develop a primary viral pneumonia, sometimes leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome and death.3,4 Many, but not all, patients with severe disease have pregnancy, obesity, or underlying disease states such as asthma, obstructive airways disease, diabetes, and chronic cardiovascular or renal disease. The disease associated with H1N1pdm so far appears to be comparable with that of seasonal influenza and less severe than that seen in the 1918 pandemic or in zoonotic disease caused by highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1. However, unlike seasonal influenza where morbidity and mortality are mainly seen in the elderly, pandemic H1N1pdm appears to spare this age-group, possibly because of the presence of cross-neutralizing antibody generated by prior repeated seasonal H1N1 infection.5 In California, the median age of all cases was 17 years, of hospitalized cases 26 years, and for fatal cases was 45 years.

It is therefore important to understand how the pathogenesis and tissue tropism of H1N1pdm virus in humans differs from seasonal influenza viruses. However, there is so far limited information in this regard. The H1N1pdm virus does not possess the genetic motifs of virulence associated with either the HPAI H5N1 or 1918 H1N1 viruses.2 In experimentally infected ferrets, macaques, and mice, H1N1pdm causes moderately more severe illness compared with seasonal influenza although being much less virulent than HPAI H5N1 or the 1918 pandemic Spanish flu virus.6,7,8 In these animal models, H1N1pdm virus was able to infect the alveolar epithelium more readily than seasonal H1N1 virus, but whether this holds true for humans is not known.7 Though H1N1pdm was initially reported to have a predominantly α2-6 sialic acid (Sia) receptor binding preference8 similar to human seasonal influenza viruses, recent glycan array data indicates that there is binding to both “human” Sia α2-6 and “avian” Sia α2-3.9 H1N1pdm virus differs from seasonal influenza viruses in their ability to infect and cause illness in mice without prior adaptation. As the mouse respiratory tract has a predominance of Sia α2-3, rather than Sia α2-6 receptors, these findings support the contention that H1N1pdm viruses have a broader Sia receptor binding profile.8 Taken together, these observations suggest that H1N1pdm virus differs in subtle but important ways from seasonal influenza viruses in receptor usage and tissue tropism, and this may be important in its pathogenesis and transmission.

Cytokine dysregulation is believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of human disease caused by HPAI H5N1 as well as the 1918 pandemic H1N1 viruses.10,11,12,13,14 It is not known whether the H1N1pdm virus differs from seasonal influenza in the induction of proinflammatory host responses in human tissues. The lungs of H1N1pdm-infected mice had a markedly different cytokine profile when compared with seasonal influenza infected animals with elevated levels of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10, and interferon (IFN)-γ. The lungs of H1N1pdm-infected macaques also had higher levels of chemokines MCP-1, MIP-1α, IL-6, and IL-18.6 However, it is not known whether these host responses simply reflect the greater or more extensive replication of the H1N1pdm virus in the lung when compared with seasonal influenza viruses or are attributable to intrinsic differences in the virus itself being able to induce a more potent innate host response as occurs with the highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus. When primary human cells (macrophages and type I-like pneumocytes) are infected with seasonal and HPAI H5N1 influenza viruses of comparable infectious titers, the HPAI H5N1 viruses differentially hyperinduce a range of proinflammatory responses over a single virus replication cycle.10,11,14 Thus it is clear that the H5N1 virus has inherent properties that lead to an exaggerated innate immune response. It is relevant to use a similar approach to investigate the host innate immune responses induced by pandemic H1N1pdm compared with that of seasonal influenza H1N1 virus in primary human respiratory epithelium.

We have previously used ex vivo cultures of nasopharynx, tonsillar tissue, and lung for investigating virus tropism.15 We have also established in vitro cultures of polarized primary human respiratory epithelial cells, including type I–like alveolar epithelial cells, nasopharyngeal epithelial cells, and differentiated bronchial epithelial cells for investigating tissue tropism and innate immune host responses elicited by influenza viruses.10,14,15 These in vitro cultures of bronchial epithelium differentiated at an air–liquid interface (ALI) provide a good representation of the human bronchial epithelium and have a ciliated epithelium as well as mucus producing goblet cells. We have also recently established ex vivo tissue culture models of human conjunctival epithelium. We now use these ex vivo human tissue cultures as well as the primary human respiratory epithelial cell cultures to compare the virus replication competence, cell tropism, and host innate immune responses of the pandemic H1N1pdm virus with that of seasonal influenza H1N1 viruses and, where relevant, avian HPAI H5N1 and H7N7 viruses.

We demonstrate that whereas seasonal H1N1 and pandemic H1N1pdm viruses replicate comparably in ex vivo cultures of human nasopharynx and lung tissues, the human conjunctiva is preferentially infected by H1N1pdm rather than seasonal influenza H1N1 or H3N2 viruses. Pandemic H1N1pdm replicates more efficiently than seasonal H1N1 virus in differentiated bronchial epithelial cells in vitro at 33°C, but the two viruses replicate comparably at 37°C. We also demonstrate that the pandemic H1N1pdm virus does not differ from the human seasonal influenza viruses in their ability to induce proinflammatory cytokines and therefore does not appear to have the same potential to induce cytokine dysregulation as that manifested by HPAI H5N1 or the 1918 H1N1 virus.

Materials and Methods

Viruses

The viruses used in these studies were the pandemic virus A/HongKong/415742/09 (H1N1pdm), seasonal viruses A/HongKong/54/98 (H1N1), A/HongKong/403721/2009 (H1N1) and A/Oklahoma/1992/05 (H3N2), and two avian influenza viruses isolated from humans, A/Vietnam/3046/04 (H5N1) and A/Netherland/33/03 (H7N7). A/Oklahoma/1992/05 (H3N2) was chosen because of the availability of glycan array data demonstrating a restricted Sia α2-6Gal–binding profile.16 The viruses were initially isolated and passaged in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells. The virus stock was aliquoted and then titrated to determine tissue culture infection dose 50% (TCID50) in MDCK cells. The experiments were performed in a Bio-safety level 3 (BSL-3) facility at the Department of Microbiology, The University of Hong Kong. Table 1 summarizes all of the influenza A viruses used in this study and their abbreviations.

Table 1.

List of Influenza A Viruses Used in this Study

| Subtype | Name | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| H1N1 | A/Hong Kong/54/1998 | HK98/H1N1 |

| H1N1 | A/Hong Kong/463721/2009 | HK09/H1N1 |

| H1N1 | A/Hong Kong/415742/2009 | HK09/H1N1pdm |

| H3N2 | A/Oklahoma/1992/2005 | OK05/H3N2 |

| H7N7 | A/Netherland/33/2003 | NL03/H7N7 |

| H5N1 | A/Vietnam/3046/2004 | VN04/H5N1 |

In Vitro and ex Vivo Cell Cultures

Primary human alveolar type I–like pneumocytes, well-differentiated bronchial epithelial cells and nasopharyngeal epithelial cells were derived and cultured as previously described10,14,15,17,18,19,20 with modifications.

Alveolar Type I–Like Pneumocytes Isolation

Primary type I–like pneumocytes were isolated using human nonmalignant lung tissue obtained from patients undergoing lung resection in the Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong SAR, under a study approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong and Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster, and written informed consent was provided by each patient. Briefly, after removing visible bronchi, the lung tissue was minced into pieces of >0.5 mm thickness using a tissue chopper and washed with BSS containing Hanks balanced salt solution (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) with 0.7 mmol/L sodium bicarbonate (Gibco) at pH 7.4 for 3 times to partially remove macrophages and blood cells. The tissue was digested using a combination of 0.5% trypsin (GIBCO BRL, Gaithersburg, MD) and 4 U/ml elastase (Worthington Biochemical Corporation, Lakewood, NJ) for 40 minutes at 37°C in a shaking water-bath. The digestion was stopped by adding DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco) with 40% FBS in and DNase I (350 U/ml) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Cell clumps were dispersed by repeatedly pipetting the cell suspension for 10 minutes. A disposable cell strainer (gauze size of 50 μm; BD Science, Palto-Alto, CA) was used to separate large undigested tissue fragments. The single cell suspension in the flow-through was centrifuged and resuspended in a 1:1 mixture of DMEM/F12 medium and small airway basal medium (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) supplemented with 0.5 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (hEGF), 500 ng/ml epinephrine, 10 μg/ml transferrin, 5 μg/ml insulin, 0.1 ng/ml retinoic acid, 6.5 ng/ml triiodothyronine, 0.5 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 30 μg/ml bovine pituitary extract, and 0.5 mg/ml BSA together with 5% FBS and 350 U/ml DNase I. The cell suspension was plated on tissue culture–grade plastic flask (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) and incubated in a 37°C water-jacketed incubator with 5% CO2 supply for 90 minutes. The nonadherent cells were layered on a discontinuous cold Percoll density gradient (densities 1.089 and 1.040 g/ml) and centrifuged at 25g for 20 minutes without brake. The cell layer at the interface of the two gradients was collected and washed four times with BSS to remove the Percoll. The cell suspension was incubated with magnetic beads coated with anti-CD14 antibodies at room temperature for 20 minutes under constant mixing. After the removal of the beads using a magnet (MACS CD14 MicroBeads, Miltenyi Biotech GmbH, Gladbach, Germany), cell viability was assessed by trypan-blue exclusion. The purified pneumocyte suspension was resuspended in small airway growth medium (Lonza) supplemented with 1% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and plated at a cell density of 3 × 105 cells/cm2. The cells were maintained in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2, 37°C) under liquid-covered conditions, and growth medium was changed daily starting from 60 hours after plating the cells. When the cell layer approached 75% confluence, the pneumocytes were detached Hanks buffered saline solution trypsin/EDTA and subcultured for the experiments.

Culture of Well-Differentiated Normal Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells

Human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells were purchased as cryopreserved vials (Lonza). NHBE cells were plated into a T175 tissue culture grade culture flask in a density of 500 cells/cm2 for cell proliferation. Bronchial epithelial basal medium (Lonza Walkersville, Inc.) was supplemented with growth factor and hormones as stated in the suppliers instructions. After subculture, they were plated to a cell density of 2.5 × 105 cells/cm2 on human collagen IV (BD Science)–coated transwell inserts (Corning). Bronchial epithelial growth medium (Lonza Walkersville, Inc.) medium was supplemented with the retinoic acid concentration adjusted to 10−7 mol/L. Medium was changed every 48 hours until the cell layer reached confluence. An ALI was then established by removing the culture medium from the apical compartment. Thereafter, medium was changed in the basolateral compartment every 48 hours until day 21 of ALI culture. The apical compartment was gently washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) once a week to remove accumulated mucus and debris. The transepithelial resistance was measured by epithelial voltohmeter (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, Fla.). At day 21 of ALI culture, the NHBE cells became well differentiated and ready for use. The transwell cultures were collected and fixed with 10% formalin, paraffin embedded, and then cross-sectioned for histological examination. Slides were stained using hematoxylin-eosin. Ciliated cells were further identified by FITC-conjugated β-tubulin antibody (Sigma, Saint Louis, MO) and goblet cells were identified by biotinylated MUC5AC antibody (Invitrogen, San Francisco, CA).

Culture of Nasopharyngeal Epithelial (NPE) Cells

The nasopharyngeal biopsy was cut into 2- to 3-mm fragments and placed onto a 6-cm-sized Falcon culture dish (BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA) containing 2 ml of RPMI 1640 culture medium (Gibco) supplemented with 1% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (FBS), 0.25 μmol/L transferrin, 3.32 nmol/L hEGF, 0.7 μmol/L insulin, 0.5 μmol/L phosphoethanolamine, 0.5 μmol/L ethanolamine, 10 nmol/L tiodo-L-thyronine, 2 μmol/L hydrocortisone, 2.7 μmol/L L-epinephrine, 2 mmol/L l-glutamine, 0.03 μmol/L sodium selenium, 1 nmol/L molybdic acid, 0.5 nmol/L stannous chloride, and 0.75 nmol/L nickel sulfate. The medium had 0.4 mmol/L calcium, which facilitated the attachment of explants to the culture surfaces. After 7 to 10 days of culture, the proliferative epithelial outgrowth from the explants were trypsinized and propagated at a splitting-ratio of 3 in a 1:1 mixture of Defined Keratinocyte-SFM (Gibco) and EpiLife medium with full supplements (Sigma-Aldrich). The cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a water-jacketed incubator. The calcium concentration in this mixed medium formulation was below 0.08 mmol/L to stimulate the proliferation of the primary nasopharyngeal epithelial cells and suppress the growth of contaminating fibroblasts.

Ex Vivo Culture of Conjunctiva, Nasopharynx, Bronchi, and Lung

Fresh conjunctiva tissues were obtained from 20 individuals who were undergoing excision for pterygium during surgical management. Biopsies of nasopharyngeal tissue (n = 6) were obtained from patients undergoing elective nasopharyngoscopy as detailed earlier.15 Bronchi (n = 18) and lung tissues (n = 18) were obtained from lung carcinoma patients having surgical resection of lung tissue. The biopsies or tissue fragments of normal nonmalignant tissue that was excess to the requirements of clinical diagnosis were used. All of the studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong and Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster, and a written informed consent was provided by each patients. The lung tissue fragments were placed into culture medium (F-12K nutrient mixture with l-glutamine, and antibiotics) in 24-well tissue culture plates incubated at 37°C for viral infection experiments. The conjunctival, nasopharyngeal, and bronchial biopsies or tissue fragments were placed into culture medium (F-12K nutrient mixture with l-glutamine, and antibiotics) incubated at 33°C (except the bronchial biopsy, which was incubated at 37°C) with a sterile surgical pathology sponge to establish an ALI condition in 24-well culture plates for both conjunctiva, nasopharynx and bronchi ex vivo culture (Corning, New York, NY) for viral infection experiments.

Experimental Infection with Influenza Viruses

The experimental conditions and multiplicity of infection (MOI) used in the ex vivo and in vitro experiments is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary Table Showing the Experimental Conditions, MOIs, and Virus Titer Used in the ex Vivo and in Vitro Experiments

| Experiment model | Region | Incubation temperature | MOI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ex vivo | Conjunctiva* | 33°C | UD |

| Nasopharynx | 33°C | UD | |

| Bronchi | 37°C | UD | |

| Lung | 37°C | UD | |

| In vitro | Nasopharyngeal epithelial cells | 33°C and 37°C | 0.01† and 2‡ |

| Bronchial epithelial cells | 33°C and 37°C | 0.01† and 2‡ | |

| Type I-like pneumocytes | 37°C | 0.01† and 2‡ |

Conjunctiva tissues were infected with all the viruses listed in Table 1, while the other respiratory tissue and epithelial cells were infected with HK98/H1N1 and HK09/H1N1pdm.

MOI† used for replication kinetics study and

Infection of Respiratory Epithelial Cell in Vitro

Respiratory epithelial cell cultures were infected with influenza A viruses at a MOI of 0.01 for the analysis of virus replication and MOI of 2 for the analysis of cytokine and chemokine expression. MEM medium (Gibco) with 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin was used as inoculum in the mock infected cells. The cell culture was incubated with the virus inoculum for 1 hour in a water-jacketed 37°C or 33°C incubator with 5% CO2 (Table 2). After the incubation period the cells were rinsed 3 times with warm PBS and replenished with the appropriate growth medium. The infected cells were harvested for mRNA collection at 6 hours and 24 hours postinfection and viral M gene was quantified using qPCR as described.10,14 Productive viral replication was assayed by titrating the cell-free supernatant collected at 1, 24, 48, 72 hours by titration in quadruplicate in MDCK cells and expressed as 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50).

Influenza Virus Infection of ex Vivo Culture

Ex vivo conjunctival cultures were infected with influenza A viruses of subtypes H7N7, H5N1, H3N2, H1N1, and H1N1pdm within 2 hours of collection. Five biopsies served as uninfected controls, and two were infected with UV light inactivated VN04/H5N1 virus as controls. The viruses were used at a titer of 1 × 106 TCID50/ml (a similar titer to that used by Shinya et al21) for infecting the ex vivo cultures. The biopsy or tissue fragments were incubated at 33°C on the culture sponge to establish an ALI for time periods ranging from 0 to 24 hours at which time the tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and processed for paraffin embedding and immunohistochemistry using a mouse anti-influenza nucleoprotein antibody (HB65, EVL Laboratories, The Netherlands). To determine productive viral replication, conjunctival and biopsies were cultured in 1 ml of F12K with 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 33°C, and infected with influenza A viruses at a titer of 1 × 106 TCID50/ml. After 2 hours infection the unattached virus was removed by washing. At 0 and 24 hours after washing, 130 μl of medium was removed and stored at −80°C for virus titration in MDCK cells. Increasing virus titers in the cell supernatants provided evidence of productive virus replication. At the end of 24 hours the tissues were then fixed in formalin, and immunohistochemistry for influenza antigen was performed.

Fragments of normal nasopharynx, bronchi, and lung tissues were cut into multiple 2- to 3-mm fragments and infected in parallel with influenza A viruses at a titer of 1 × 106 TCID50/ml. Human influenza viruses HK98/H1N1 and HK09/H1N1pdm were tested in parallel. These tissues fragments were infected as above and incubated for 1, 24, and 48 hours at 37°C. They were then fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and processed for paraffin embedding and immunohistochemistry (see below). Additional tissue fragments were infected with influenza A virus at 37°C and after 2 hours, unbound virus was removed, and viral yield in the cell-free supernatant was assessed at 1 and 24 hours (for nasopharynx) and 1, 24, and 48 hours (for lung and bronchi) by titration in quadruplicate in MDCK cells.

Viral Titration by TCID50 Assay

A confluent 96-well tissue culture plate of MDCK cells was prepared one day before the virus titration (TCID50) assay. Cells were washed once with PBS and replenished with serum-free MEM medium supplemented with 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 2 μg/ml of tosylsulfonyl phenylalanylchloromethyl ketone (TPCK)–treated trypsin. Serial dilutions of virus supernatant, from 0.5 log to 7 log, were performed before adding the virus dilutions onto the plates in quadruplicate. The plates were observed for cytopathic effect daily. The end point of viral dilution leading to CPE in 50% of inoculated wells was estimated using the Karber method.22

Immunohistochemical Staining for Influenza A Virus Antigen

Immunohistochemical staining of the conjunctiva and respiratory tract tissue was performed for the influenza nucleoprotein as follows. The tissue sections with incubated with 0.05% Pronase (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) in 0.1% CaCl2 pH 7.8 at 37°C for 2 minutes, blocked with 3% H2O2 in TBS for 10 minutes, followed by treatment with an avidin/biotin blocking kit (Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA). After blocking with 10% normal rabbit serum for 10 minutes at room temperature, the sections were incubated with 1/100 (15 μg/ml) HB65 (EVL anti-influenza NP, subtype A) antibody for 1 hour at room temperature followed by biotinylated rabbit anti-mouse (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark) diluted 1/100 for 30 minutes at room temperature. After incubation with strep-ABC complex (Dako Cytomation) diluted 1/100 for 30 minutes at room temperature, the sections were developed with 0.5 mg/ml DAB (Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.02% H2O2 for 20 minutes and then microwaved in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer pH 6.0 for 20 minutes to expose the second antigen.

Lectin Histochemistry

Sections of ex vivo conjunctival biopsies used for the virus infections experiments were processed similar to the procedure for immunohistochemistry. The detection of Sia on ex vivo tissue sections was performed using lectin cytochemistry. Tissue fragments were washed and fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin followed by staining with the Roche Dig Glycan Detection Kit as per manufacturer’s instructions. Lectins recognizing different penultimate structures as well as the Sia linkages (α2-6 or α2-3 to either Galβ1-4GlcNAc or Galβ1-3GalNAc) were used: Peanut agglutinin (PNA; binding to Galβ1-3GalNAc), Maackia amurensis agglutinin (MAA; which binds to a number of glycans including α2-3-linked Sia), and HRP-conjugated Sambucus nigra agglutinin (SNA; which binds α2-6-linked Sia).

Desialylation of Conjunctival ex Vivo Tissues

The detection of surface Sia on ex vivo tissue sections was performed using lectin cytochemistry. Tissue fragments were exposed to 100 U/ml of DAS181, a sialidase fusion protein provided by NexBio Inc (CA) for 2 hours followed by washing and fixation in 10% neutral buffered formalin followed by staining with the lectins SNA, MAA, and PNA as indicated above. Infectious viral yield in the cell-free supernatant was assessed at 1 and 24 hours in the cell culture experiments with and without the treatment of DAS181 before influenza virus infection by viral titration described above. Lectin binding was also performed to detect total Sia in the ex vivo tissues before and after DAS181 treatment.

Quantification of Cytokine and Chemokine Profile by RT-qPCR and ELISA

mRNA from infected cells was extracted at 6, 8, and 24 hours postinfection using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and treated with DNase. cDNA was synthesized with Oligo-dT primers and Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) and quantified by real-time quantitative PCR analysis with a LightCycler (Roche). The gene expression profile for cytokines, tumor necrosis factor-α and IFN-β and chemokines (IP-10, RANTES) and viral matrix gene were quantified and normalized using the housekeeping gene product β-actin mRNA. The primers and methods used for these assays have been reported previously.10,11 The concentrations of IFN-β, RANTES, and IP-10 proteins in culture supernatants collected at 8 hours or 24 hours postinfection of the influenza viruses, and infected cells were measured by ELISA assay as recommended by the manufacturer (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

Statistical Analysis

The differences of log10-transformed viral titers among different viruses at different time points of postinfection and the quantitative cytokine and chemokine mRNA and protein expression profile of influenza virus–infected cells was compared using one-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni multiple-comparison test. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. The statistical analysis was performed using Graph-pad Prism 5.

Results

HK09/H1N1pdm Infection in Conjunctiva Biopsy ex Vivo

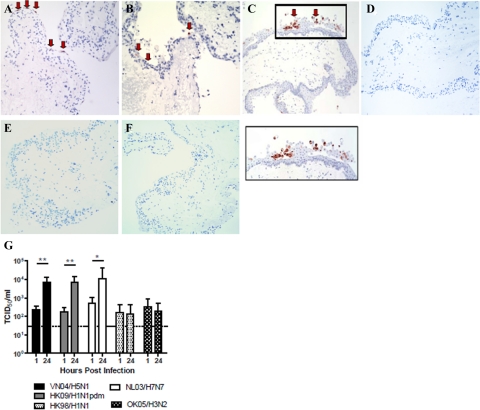

We infected cultures of ex vivo tissues within 2 hours of collection with human seasonal influenza viruses HK98/H1N1 and HK09/H1N1, OK05/H3N2, pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm, and avian influenza viruses VN04/H5N1 and NL03/H7N7. Immunohistochemistry (Figure 1, A–C) revealed that pandemic influenza HK09/H1N1pdm as well as avian VN04/H5N1 and NL03/H7N7 viruses readily infected conjunctival epithelial cells resulting in >10-fold increase in viral titers at 24 hours after infection (Figure 1G) indicating productive viral replication. There was no evidence of infection when UV-inactivated HK09/H1N1pdm, NL03/H7N7, or VN04/H5N1 viruses were used to infect the conjunctival cultures (data not shown). H7 and H5 subtype avian influenza viruses are known to replicate in human ocular epithelium,23,24 but there are no previous data on the replication of pandemic H1N1pdm at this site. On the other hand, there was no expression of viral antigen (Figure 1D to F) or increase in virus titers (Figure 1G) in conjunctival ex vivo cultures infected with seasonal HK98/H1N1 (Figure 1D), HK09/H1N1 (Figure 1E), or OK05/H3N2 (Figure 1F) virus–infected tissues or in mock-infected tissues.

Figure 1.

Ex vivo organ cultures of conjunctiva infected with (A) VN04/H5N1, (B) NL03/H7N7, and (C) HK09/H1N1pdm at 24 hours postinfection showing positive staining for influenza A nucleoprotein (reddish brown with arrow). Negative staining for influenza A nucleoprotein in (D) HK98/H1N1, (E) OK05/H3N2, and (F) HK09/H1N1 infected conjunctival tissues (G). Conjunctival biopsies infected with 106 TCID50/ml of influenza VN04/H5N1, HK09/H1N1pdm, and NL03/H7N7 viruses demonstrate an increase in viral yield, whereas HK98/98 and OK05/H3N2 demonstrate no productive replication. The chart shows the mean and the SE of the virus titer pooled from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Horizontal dotted line denotes detection limit of TCID50 assay.

Sia Receptor Distribution on Human Conjunctival Epithelium

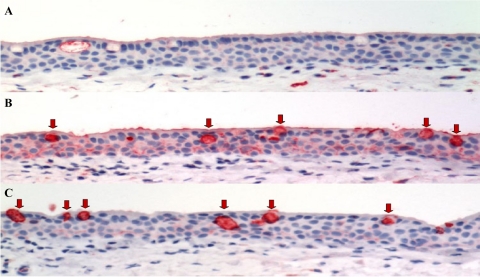

Lectin histochemistry on the ex vivo conjunctival biopsies using SNA (which recognizes the human influenza receptor Sia α2-6) and MAA (which recognizes the avian influenza receptor Sia α2-3 but also binds non-sialyated glycans25) showed that SNA binding was similar to that reported previously in normal human conjunctival epithelium26,27 with weak binding to the basal epithelium and the mucins present in the secretory goblet cells of the conjunctiva (Figure 2A). The MAA bound strongly to the basal and surface epithelium, and there was strong binding to the mucins present within the goblet cells (Figure 2B). Minimal PNA binding was seen in the epithelium, but it bound strongly to the mucins in the goblets cells (Figure 2C). After the removal of Sia from the adjacent glycan structures present on the surface of cells28 by sialidase DAS181 treatment, we showed that SNA binding was totally abolished, MAA binding was significantly reduced, but still with some binding to the mucins present within the cytoplasm of the goblet cells (Figure 3, A and B). DAS181 treatment led to increased exposure of the subterminal polysaccharide structures (such as Galβ1-3GalNAc) and thus an increased binding with PNA (Figure 3C). There was inhibition of replication of HK09/H1N1pdm in human conjunctiva ex vivo after sialidase treatment (Figure 3D) as determined by viral yield in culture supernatants, which is in keeping with the glycan array data that HK09/H1N1pdm may use Sia α2-3Gal in addition to Sia α2-6Gal receptors for infection.9

Figure 2.

Distribution of Sia on conjunctival tissue ex vivo. Sia in α2-6 linkages were stained using SNA, Sia in α2-3 linkages were stained using MAA, and the Galβ1-3GalNAc were stained using PNA. The conjunctival tissues show negative/weak positive binding of SNA on the conjunctival epithelium (A), whereas there is a strong positive binding of the conjunctival epithelium for MAA (B) and a weak PNA staining (C). The goblet cells of the conjunctival epithelium (B and C) show a strongly positive intracytoplasmic binding for both MAA and PNA (arrow). AEC stain with hematoxylin counterstain.

Figure 3.

Human conjunctival tissues were incubated with sialidase, DAS181 (100 U/ml) for 2 hours at 37°C and fixed. Sia in α2-6 linkages (A) was stained in red using SNA, Sia in α2-3 linkages (B) was stained using MAA, and Galβ1-3GalNAc (C), which is exposed after the desialyation, was stained using PNA. D: Viral replication in conjunctival biopsies infected with 106 TCID50/ml of influenza viruses (VN04/H5N1 and HK09/H1N1pdm) with and without DAS181 treatment by TCID50 assay. The chart shows the mean and the SE of the virus titer pooled from three independent experiments. **P < 0.01.

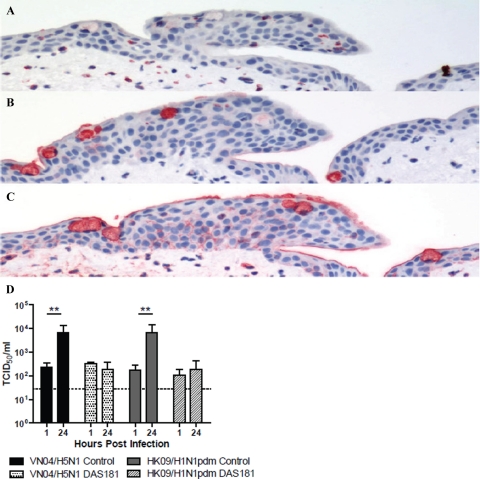

HK09/H1N1pdm Infection in Nasopharynx, Bronchi, and Lung Biopsies ex Vivo

By immunohistochemistry, we found evidence that pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm (Figure 4, A, D, and G) and seasonal HK98/H1N1 (Figure 4, B, E, and H) readily infected the epithelium of the nasopharynx, bronchi, and lung. In parallel, there was evidence of productive virus replication with increasing virus titers in pandemic H1N1pdm and seasonal H1N1-infected nasopharygeal, bronchial, and lung ex vivo cultures (Figure 4, C, F, and I, respectively). Pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm titers in the bronchus had peaked by 24 hours, whereas seasonal H1N1 virus titers continued to further increase until 48 hours postinfection (Figure 4F). Mock infected control tissues revealed no evidence of infection by immunohistochemistry or virus yield (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Cellular localization of ex vivo infection of the upper and lower respiratory tract by influenza A viruses (A and B) nasopharynx, (D and E) bronchi, and (G and H) lung infected with influenza HK09/H1N1pdm and HK98/H1N1 viruses, showing positive staining for influenza A nucleoprotein (reddish brown). Viral replication kinetics in ex vivo cultures of (C) nasopharynx, (F) bronchi, and (I) lung biopsies infected with 106 TCID50/ml of influenza viruses by virus titration. The chart showed the mean and the SE of mean of the virus titer pooled from three independent experiments.

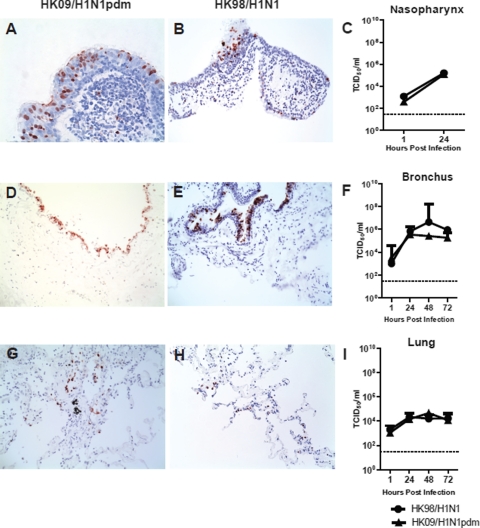

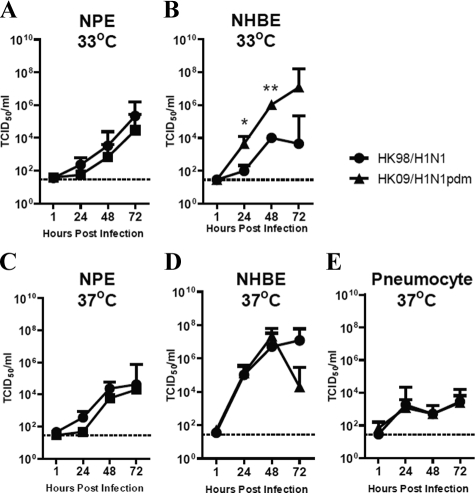

Replication Kinetics of HK09/H1N1pdm and Seasonal Influenza HK98/H1N1 Virus in NPE Cells, NHBE cells, and Alveolar Type I-Like Pneumocytes in Vitro

To extend the data we had obtained from ex vivo cultured human respiratory tissues, we performed experiments on primary nasopharyngeal epithelial (NPE) cells, well differentiated NHBE cells, and type I–like pneumocytes in vitro. HK09/H1N1pdm and HK98/H1N1 viruses replicated comparably in NPE cells at both 33°C and 37°C (Figure 5, A and C). Virus yields were tested on the apical surface of the differentiated bronchial epithelium, and both pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm and seasonal HK98/H1N1 viruses replicated well in NHBE cells at 37°C (Figure 5D). However, in NHBE cells infected at 33°C (Figure 5B), the titers of virus were significantly higher in pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm than the seasonal influenza HK98/H1N1 virus from 24 to 72 hours postinfection. Although titers of pandemic H1N1pdm virus continued to increase between 48 to 72 hours in H1N1pdm-infected cells, they plateaued with seasonal HK98/H1N1 further enhancing the difference between these two viruses. There was low-level replication of the two viruses on type I-like pneumocytes at 37°C (Figure 5E), although achieving much lower titers when compared with NPE or NHBE cells. Replication at 33°C was not tested in type I-like pneumocytes as this was not considered physiologically relevant in the alveolar spaces.

Figure 5.

Replication kinetics of influenza A viruses in respiratory epithelial cells in vitro by virus titration expressed in TCID50/ml, (A) NPE cells cultured at 33°C, and (C) NPE cells cultured at 37°C; (B) NHBE cells cultured at 33°C and (D) NHBE cultured at 37°C; (E) Type-I like pneumocytes cultured at 37°C. The chart showed the mean and the SE of mean of the virus titer pooled from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

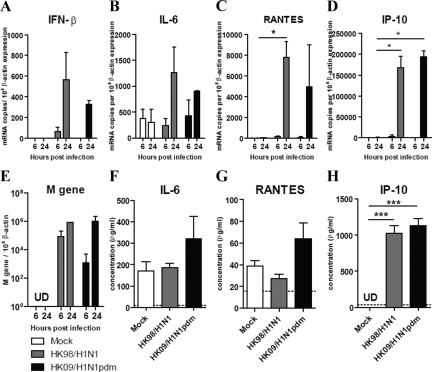

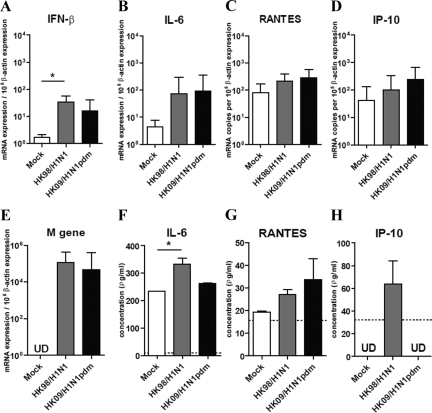

Cytokine and Chemokine Expression Profile in NHBE and Alveolar Type I–Like Pneumocytes Infected with Pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm and Seasonal Influenza HK98/H1N1 Virus

We next investigated the expression of cytokine and chemokine induction by pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm and seasonal influenza HK98/H1N1 virus–infected NHBE cells and alveolar type I–like pneumocytes (Figures 6 and 7, respectively). The efficiency of influenza replication in these cells was assayed using quantitative real-time PCR for the influenza matrix gene (Figures 6E and 7E).

Figure 6.

Cytokine and chemokine gene and protein expression in NHBE after influenza virus infection. The cytokine (A) IFN-β, (B) IL-6, and chemokine (C) RANTES, (D) IP-10, and (E) influenza matrix (M) gene expression from NHBE infected with influenza A viruses at 6 and 24 hours postinfection. Cytokine and chemokine protein secretion (F) IL-6, (G) RANTES, and (H) IP-10 at 24 hours post influenza A virus infection. The graph shows the mean and the SE of mean from three representative experiments. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Horizontal dotted line denotes detection limit of ELISA assay.

Figure 7.

Cytokine and chemokine gene and protein expression in alveolar type I–like pneumocytes after influenza A virus infection. The cytokine (A) IFN-β, (B) IL-6, and chemokine (C) RANTES, (D) IP-10, and (E) influenza matrix (M) gene expression from alveolar type I–like pneumocytes infected with influenza A viruses at 8 hours postinfection. Cytokine and chemokine protein secretion, (F) IL-6, (G) RANTES, and (H) IP-10 at 8 hours postinfection of the pandemic influenza H1N1pdm and seasonal influenza H1N1 viruses. For comparison, the cytokine proteins secretion inducted by the infection of highly pathogenic influenza H5N1 virus in alveolar type I–like pneumocytes are: IL-6 (602 ± 21 pg/ml), RANTES (526 ± 75 pg/ml), and IP-10 (1313 ± 161 pg/ml). The graph shows the mean and the SE of mean from three representative experiments. *P < 0.05.

The cytokine (IFN-β and IL-6) chemokine (RANTES and IP-10) mRNA expression profiles at 6 and 24 hours postinfection were similar in pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm and seasonal HK98/H1N1 virus–infected NHBE cells (Figure 6, A–D). IL-6, RANTES, and IP-10 protein levels in the culture supernatant measured by ELISA on the apical aspect of the polarized NHBE cells at 24 hours postinfection were also comparable (Figure 6, F–H). We failed to detect any IFN β proteins in the supernatant of NHBE cells after influenza virus infection (data not shown), but this is likely because of poor sensitivity of the IFN β ELISA (limit of detection was 250 pg/ml).

In alveolar type I–like pneumocytes, the cytokine (IFN-β and IL-6) chemokine (RANTES and IP-10) mRNA expression profiles at 8 hours postinfection were similar in pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm and seasonal HK98/H1N1 virus–infected type I–like pneumocytes (Figure 7, A–D). IL-6, RANTES, and IP-10 protein levels in the culture supernatant measured by ELISA at 8 hours postinfection were also comparable between the two viruses (Figure 7, F–H). Again, we failed to detect any IFN β proteins in the supernatant of type I–like pneumocytes after influenza virus infection (data not shown). In contrast with highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 virus (see data in legend to Figure 7), pandemic H1N1pdm did not differ from seasonal influenza H1N1 virus in its intrinsic capacity for cytokine dysregulation.

Inactivation of the virus by UV irradiation and high temperature (70°C; 15 minutes) before infection of the NHBE cells and alveolar type I–like pneumocytes abolished cytokine induction (data not shown). This suggests that virus replication was required for cytokine induction and rules out the possibility that endotoxin contamination in virus stocks contributed to the observed cytokine responses. An increase in the MOI of influenza virus up to five did not result in changes in the cytokine mRNA expression profile of the two influenza viruses (data not shown).

Discussion

Using ex vivo and in vitro cultures representing the upper and lower respiratory epithelium, we have compared the pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm virus with seasonal influenza virus HK98/H1N1 in regard to their tropism, replication competence, and innate host responses. The most striking difference between these two viruses was the ability of the pandemic H1N1pdm virus to efficiently infect and replicate in ex vivo cultures of the human conjunctival epithelium. Two seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses (HK98/H1N1 and HK09/H1N1) and H3N2 virus (OK05/H3N2) failed to infect the conjunctiva, whereas the avian VN04/H5N1 and NL03/H7N7 viruses did. The human conjunctiva has been reported to lack Sia α2-6 that human influenza viruses bind to but expresses the Sia α2-3 that allows binding of avian influenza viruses. Our own studies using the lectins SNA and MAA (Figure 2) essentially confirm that these receptor distributions remain true in our ex vivo cultures when compared with human conjunctival epithelium.26,27,29 The lack of infection with the seasonal influenza and the ability of avian influenza viruses VN05/H5N1 and NL03/H7N7 that preferentially bind Sia α2-3 are in line with these expectations. The marked differences in conjunctival tissue tropism of pandemic H1N1pdm and seasonal H1N1 viruses suggest differences in receptor preference or virus replication competence in these cells. Significant differences in receptor binding profiles between seasonal and pandemic H1N1 viruses has been recently confirmed by glycan array data.9 Two different pandemic H1N1pdm virus strains had an affinity for both Sia α2-3 as well as Sia α2-6 glycans, whereas seasonal H1N1 had a more restricted binding profile to a narrower range of Sia α2-6 glycans. These findings may also explain the ability of pandemic H1N1pdm virus to cause disease in mice without prior adaptation.6 The receptors that mediate pandemic H1N1pdm infection of the conjunctiva remain to be defined, but the finding that the sialidase DAS181 efficiently blocks virus infection in the conjunctiva (Figure 3D) suggests that it is likely to be Sia in nature. Because SNA lectin staining does not recognize all of the Sia α2-6Gal glycans that may present in human conjunctiva, it is still possible that other conformations of Sia α2-6Gal may yet be used by the virus to gain entry to the conjunctival epithelium. In any event, our observation may have the practical implication that the pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm virus may have a greater potential than seasonal influenza viruses to transmit via the conjunctival route. The role of the viral hemagglutinin, neuraminidase, or other genes in the ability of the novel pandemic influenza virus to infect human conjunctival tissue can be systematically investigated using reverse genetics approaches and these studies are currently ongoing.

We furthermore demonstrate that both pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm and seasonal HK98/H1N1 viruses can efficiently and comparably infect ex vivo cultures of human nasopharynx, bronchi, and lung tissues (Figure 4). They also have comparable growth curves when infecting in vitro cultures of primary human nasopharyngeal epithelium at both 33°C and 37°C (Figure 5, A and C). Immunohistochemistry and virus growth curves show that the alveolar epithelium of ex vivo lung cultures is comparably infected by both pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm and seasonal HK98/H1N1 viruses (Figure 4, D, E, and I). This is also reflected in the in vitro cultures of type I–like pneumocytes (Figure 5E). Interestingly, HK09/H1N1pdm virus appears to replicate significantly better than seasonal H1N1 in differentiated bronchial epithelium at 33°C (Figure 5B), whereas there is no difference in growth curves of these two viruses in these cells at 37°C in the first 48 hours postinfection (Figure 5D). As the physiological temperature in the upper respiratory tract and conducting airways may be lower than the core-body temperature of 37°C, the differences in replication competence at 33°C in differentiated human bronchial epithelial cells may be relevant in contributing to the modestly increased virulence of HK09/H1N1pdm virus in humans and in animal models.

In contrast to HPAI H5N1 viruses,10,11,14 the pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm virus did not induce higher levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines from NHBE cells or type I–like pneumocytes when compared with seasonal influenza viruses (Figures 6 and 7). Therefore, the pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm virus is unlikely to have an intrinsic capacity for cytokine hyperinduction and enhanced pathogenesis by the route of immunopathogenesis. In any event, these findings would suggest that there is little biological rationale for immunomodulatory treatment in pandemic H1N1pdm disease on the basis of intrinsic properties of this virus. It is to be noted, however, that extensive replication of a virus in the alveolar epithelium is by itself likely to induce alveolar damage and subsequent host responses that may lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome, and these complications may have to be managed on their own merits.

In conclusion, our finding that the pandemic HK09/H1N1pdm virus (but not seasonal HK98/H1N1 virus) infects conjunctival epithelium suggests that the eye may be an important route for acquiring infection with HK09/H1N1pdm as compared with seasonal influenza viruses. Furthermore, this observation implies important differences in receptor preference and tissue tropism between the pandemic H1N1 and seasonal influenza viruses, which may have relevance in pathogenesis. The increased replication competence of the HK09/H1N1pdm virus in the bronchial epithelium at 33°C together with differences in tissue tropism in human may be relevant to the modest increase in virulence of this virus compared with seasonal influenza viruses in the current influenza pandemic. On the other hand, the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus is comparable with seasonal influenza in inducing host innate responses and does not have the intrinsic properties of cytokine dysregulation possessed by HPAI H5N1 virus or the 1918 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus.11,12,13 The virus receptor expression in the ex vivo lung cultures mimics what is seen in human tissue,17,25 highlighting the value of ex vivo cultures in providing physiologically relevant insights into pathogenesis in humans. However, no ex vivo culture or animal model can completely reproduce the state of the human respiratory tract, and our results therefore need to be interpreted in the context of these limitations. Overall the experimental findings are compatible with the clinical and epidemiological observations on pandemic influenza H1N1pdm virus, which suggests that its severity is not markedly different from that of seasonal influenza H1N1 viruses. The increased burden in hospitalization and need for intensive care management may well be more likely attributable to the much larger number of people infected with an antigenically novel virus toward which a substantial segment of the population remains immunologically naïve together with subtle differences in virus tropism and replication competence.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the help of Kevin Fung and Yi Jun Chu for the immunohistochemistry and lectin staining. We thank Elaine Y.L. Yip and Deng Wen for the technical assistance in the primary culture of nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. We thank Gillian M. Air (Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Oklahoma Health Science Center) for providing the influenza H3N2 virus strain and Mang Yu (NexBio Inc.) for providing the sialidase fusion protein, DAS181, used in this study.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Joseph Malik Sriyal Peiris, M.D. D.Phil. or Dr. Michael Chi Wai Chan, Ph.D., Department of Microbiology, University Pathology Building, Queen Mary Hospital, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR, China. E-mail: malik@hkucc.hku.hk or mchan@hkucc.hku.hk.

Supported by Research Fund for Control of Infectious Disease grant (Ref: LAB-15, RFCID commissioned study on human swine influenza virus and RFCID grant, reference no: 06060552, 08070842) from the Research Fund for Control of Infectious Disease, Health, Welfare, and Food Bureau, Hong Kong SAR Government, and the General Research Fund (HKU 7612/08M and 7610/09M to M.C.W.C., HKU 7530/06M to L.L.M.P and HKU 7735/07M to J.M.N), Research Grants Council, Hong Kong SAR Government; Small project funding (reference no: 200907176007 to R.W.Y.C), The University of Hong Kong; National Institutes of Health (NIAID contract HHSN266200700005C) and AoE Funding (AoE/M-12/06) from the Area of Excellence Scheme of the University Grants Committee, Hong Kong SAR Government.

M.C.W.C. and R.W.Y.C. contributed equally to this study.

References

- Smith GJ, Vijaykrishna D, Bahl J, Lycett SJ, Worobey M, Pybus OG, Ma SK, Cheung CL, Raghwani J, Bhatt S, Peiris JS, Guan Y, Rambaut A. Origins and evolutionary genomics of the 2009 swine-origin H1N1 influenza A epidemic. Nature. 2009;459:1122–1125. doi: 10.1038/nature08182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann G, Noda T, Kawaoka Y. Emergence and pandemic potential of swine-origin H1N1 influenza virus. Nature. 2009;459:931–939. doi: 10.1038/nature08157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawood FS, Jain S, Finelli L, Shaw MW, Lindstrom S, Garten RJ, Gubareva LV, Xu X, Bridges CB, Uyeki TM. Emergence of a novel swine-origin influenza A (H1N1) virus in humans. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2605–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Zarychanski R, Pinto R, Cook DJ, Marshall J, Lacroix J, Stelfox T, Bagshaw S, Choong K, Lamontagne F, Turgeon AF, Lapinsky S, Ahern SP, Smith O, Siddiqui F, Jouvet P, Khwaja K, McIntyre L, Menon K, Hutchison J, Hornstein D, Joffe A, Lauzier F, Singh J, Karachi T, Wiebe K, Olafson K, Ramsey C, Sharma S, Dodek P, Meade M, Hall R, Fowler R. Critically ill patients with 2009 influenza A(H1N1) infection in Canada. JAMA. 2009;302:1872–1879. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hancock K, Veguilla V, Lu X, Zhong W, Butler EN, Sun H, Liu F, Dong L, Devos JR, Gargiullo PM, Brammer TL, Cox NJ, Tumpey TM, Katz JM. Cross-reactive antibody responses to the 2009 pandemic H1N1 influenza virus. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1945–1952. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Shinya K, Kiso M, Watanabe T, Sakoda Y, Hatta M, Muramoto Y, Tamura D, Sakai-Tagawa Y, Noda T, Sakabe S, Imai M, Hatta Y, Watanabe S, Li C, Yamada S, Fujii K, Murakami S, Imai H, Kakugawa S, Ito M, Takano R, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Shimojima M, Horimoto T, Goto H, Takahashi K, Makino A, Ishigaki H, Nakayama M, Okamatsu M, Warshauer D, Shult PA, Saito R, Suzuki H, Furuta Y, Yamashita M, Mitamura K, Nakano K, Nakamura M, Brockman-Schneider R, Mitamura H, Yamazaki M, Sugaya N, Suresh M, Ozawa M, Neumann G, Gern J, Kida H, Ogasawara K, Kawaoka Y. In vitro and in vivo characterization of new swine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses. Nature. 2009;460:1021–1025. doi: 10.1038/nature08260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munster VJ, de Wit E, van den Brand JM, Herfst S, Schrauwen EJ, Bestebroer TM, van de Vijver D, Boucher CA, Koopmans M, Rimmelzwaan GF, Kuiken T, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Pathogenesis and transmission of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza virus in ferrets. Science. 2009;325:481–483. doi: 10.1126/science.1177127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maines TR, Jayaraman A, Belser JA, Wadford DA, Pappas C, Zeng H, Gustin KM, Pearce MB, Viswanathan K, Shriver ZH, Raman R, Cox NJ, Sasisekharan R, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. Transmission and Pathogenesis of Swine-Origin 2009 A(H1N1) Influenza Viruses in Ferrets and Mice. Science. 2009;325:484–487. doi: 10.1126/science.1177238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs RA, Palma AS, Wharton S, Matrosovich T, Liu Y, Chai W, Campanero-Rhodes MA, Zhang Y, Eickmann M, Kiso M, Hay A, Matrosovich M, Feizi T. Receptor-binding specificity of pandemic influenza A (H1N1) 2009 virus determined by carbohydrate microarray. Nature Biotechnol. 2009;27:797–799. doi: 10.1038/nbt0909-797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MC, Cheung CY, Chui WH, Tsao SW, Nicholls JM, Chan YO, Chan RW, Long HT, Poon LL, Guan Y, Peiris JS. Proinflammatory cytokine responses induced by influenza A (H5N1) viruses in primary human alveolar and bronchial epithelial cells. Respir Res. 2005;6:135. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-6-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung CY, Poon LL, Lau AS, Luk W, Lau YL, Shortridge KF, Gordon S, Guan Y, Peiris JS. Induction of proinflammatory cytokines in human macrophages by influenza A (H5N1) viruses: a mechanism for the unusual severity of human disease? Lancet. 2002;360:1831–1837. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11772-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kash JC, Tumpey TM, Proll SC, Carter V, Perwitasari O, Thomas MJ, Basler CF, Palese P, Taubenberger JK, Garcia-Sastre A, Swayne DE, Katze MG. Genomic analysis of increased host immune and cell death responses induced by 1918 influenza virus. Nature. 2006;443:578–581. doi: 10.1038/nature05181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrone LA, Plowden JK, Garcia-Sastre A, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. H5N1 and 1918 pandemic influenza virus infection results in early and excessive infiltration of macrophages and neutrophils in the lungs of mice. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000115. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan MC, Chan RW, Yu WC, Ho CC, Chui WH, Lo CK, Yuen KM, Guan Y, Nicholls JM, Peiris JM. Influenza H5N1 virus infection of polarized human alveolar epithelial cells and lung microvascular endothelial cells. Respir Res. 2009;10:102. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-10-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls JM, Chan MC, Chan WY, Wong HK, Cheung CY, Kwong DL, Wong MP, Chui WH, Poon LL, Tsao SW, Guan Y, Peiris JS. Tropism of avian influenza A (H5N1) in the upper and lower respiratory tract. Nat Med. 2007;13:147–149. doi: 10.1038/nm1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumari K, Gulati S, Smith DF, Gulati U, Cummings RD, Air GM. Receptor binding specificity of recent human H3N2 influenza viruses, Virol J. 2007;4:42. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan RW, Chan MC, Wong AC, Karamanska R, Dell A, Haslam SM, Sihoe AD, Chui WH, Triana-Baltzer G, Li Q, Peiris JS, Fang F, Nicholls JM. DAS181 inhibits H5N1 influenza virus infection of human lung tissues. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:3935–3941. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00389-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray TE, Guzman K, Davis CW, Abdullah LH, Nettesheim P. Mucociliary differentiation of serially passaged normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;14:104–112. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.14.1.8534481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen G, Park SW, Nguyenvu LT, Rodriguez MW, Barbeau R, Paquet AC, Erle DJ. IL-13 and epidermal growth factor receptor have critical but distinct roles in epithelial cell mucin production. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:244–253. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0180OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao SW, Wang X, Liu Y, Cheung YC, Feng H, Zheng Z, Wong N, Yuen PW, Lo AK, Wong YC, Huang DP. Establishment of two immortalized nasopharyngeal epithelial cell lines using SV40 large T and HPV16E6/E7 viral oncogenes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1590:150–158. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00208-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinya K, Ebina M, Yamada S, Ono M, Kasai N, Kawaoka Y. Avian flu: influenza virus receptors in the human airway. Nature. 2006;440:435–436. doi: 10.1038/440435a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karber G. 50% end-point calculation. Arch Exp Pathol Pharmak. 1931;162:480–483. [Google Scholar]

- Belser JA, Wadford DA, Xu J, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. Ocular infection of mice with influenza A (H7) viruses: a site of primary replication and spread to the respiratory tract. J Virol. 2009;83:7075–7084. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00535-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis M, Geiler J, Klassert D, Doerr HW, Cinatl J. Infection of human retinal pigment epithelial cells with influenza A viruses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:5419–5425. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls JM, Bourne AJ, Chen H, Guan Y, Peiris JS. Sialic acid receptor detection in the human respiratory tract: evidence for widespread distribution of potential binding sites for human and avian influenza viruses. Respir Res. 2007;8:73. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-8-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terraciano AJ, Wang N, Schuman JS, Haffner G, Panjwani N, Zhao Z, Yang Z. Sialyl Lewis X. Lewis X, and N-acetyllactosamine expression on normal and glaucomatous eyes. Curr Eye Res. 1999;18:73–78. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.18.2.73.5377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry M, Ellingham RB, Corfield AP. Polydispersity of normal human conjunctival mucins. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:2559–2571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malakhov MP, Aschenbrenner LM, Smee DF, Wandersee MK, Sidwell RW, Gubareva LV, Mishin VP, Hayden FG, Kim DH, Ing A, Campbell ER, Yu M, Fang F. Sialidase fusion protein as a novel broad-spectrum inhibitor of influenza virus infection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1470–1479. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1470-1479.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen F, Thale A, Kohla G, Schauer R, Rochels R, Parwaresch R, Tillmann B. Functional anatomy of human lacrimal duct epithelium. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1998;198:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s004290050160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]