Abstract

Objectives

to (1) identify and quantify the types of treatment that dentists in general dental practice use to manage defective dental restorations; and (2) identify characteristics that are associated with these dentists’ decisions to replace existing restorations. The Dental Practice-Based Research Network (DPBRN) comprises dentists in outpatient practices from five regions: AL/MS: Alabama/Mississippi, FL/GA: Florida/Georgia, MN: dentists employed by HealthPartners and private practitioners in Minnesota, PDA: Permanente Dental Associates in cooperation with Kaiser Permanente’s Center for Health Research, and SK: Denmark, Norway, and Sweden.

Methods

A questionnaire was sent to all DPBRN practitioner-investigators who reported doing at least some restorative dentistry (n=901). Questions included clinical case scenarios that used text and clinical photographs of defective restorations. Dentists were asked what type of treatment, if any, they would do in each scenario. Treatment options ranged from no treatment to full replacement of the restoration, with or without different preventive treatment options. We used logistic regression to analyze associations between the decision to intervene surgically (repair or replace) and specific dentist, practice, and patient characteristics.

Results

512 (57%) DPBRN practitioner-investigators completed the survey. A total of 65% of dentists would replace a composite restoration when the defective margin is located on dentin; 49% would repair it when the defective margin is located on enamel. Most (52%) would not intervene surgically when the restoration in the scenario was amalgam. Dentists participating in solo or small private practice (SPP) chose surgical intervention more often than dentists who participate in large group practices (LGP) or in public health practices (PHP) (p<.0001). Dentists who do not routinely assess caries risk during treatment planning were more likely to intervene surgically and less likely to choose prevention treatment (p<.05). Dentists from the SK region chose the “no treatment” option more often than dentists in the other regions.

Conclusions

Dentists were more likely to intervene surgically when the restoration was an existing composite, compared to an amalgam restoration. Treatment options chosen by dentists varied significantly by specific clinical case scenario, whether the dentist routinely does caries risk assessment, type of practice, and DPBRN region.

INTRODUCTION

About half of all restorations placed in adults in general dental practice are replacements (Mjör et al., 2002; Bernardo et al., 2007). The clinical diagnosis of secondary caries or caries adjacent to a restoration is the main reason for replacing these restorations (Mjör, 1989; Qvist et al., 1990a, b; Ericson et al., 2003; Braga et al., 2007). However, the diagnosis of secondary caries as contrasted from other defects, such as marginal discolorations (Kidd, 1989; Tyas, 1991), does not have specific diagnostic criteria that are based on a single profession-wide consensus or “gold standard”. Although secondary caries is histologically similar to primary caries, its physical features can create diagnostic challenges because lesions may not always be seen at the interface between the restorative material and the tooth (Kidd, 1990). Consequently, restorations may be replaced prematurely because dentists do not have a consistent method to diagnose these lesions and therefore may treat them when treatment is not necessary.

As the population ages and life expectancy increases (CDC, 2003; Ismail, 1997), the time at which the first dental restoration is placed becomes very salient because replacement will most likely be necessary years later as predicted by the “cycle of rerestorations” (Brantley et al., 1995). Another equally important point is the development of reliable diagnostic criteria for evaluating existing restorations, because each time a restoration is replaced, more tooth structure is lost (Gordan, 2000; Gordan, 2001, Gordan et al., 2002). Therefore, the clinical evaluation of existing restorations is essential because: (1) replacement of existing restorations contributes to a major part of the dental treatment that is provided to patients in general dental practice; and (2) uncertainty exists with regard to the need to replace or repair existing restorations (Elderton and Nuttall, 1983). Improving the accuracy of caries diagnoses may reduce unnecessary treatment and dental care costs

A comprehensive review of the literature (Bader and Shugars, 1992) concluded that “the extent to which variation in dentists’ evaluation of existing restorations is associated with characteristics of the dentist and the practice is completely unknown”. To address this issue, this study sought to determine how dentists in general dental practice evaluate and treat existing restorations. Data were obtained from questionnaire responses provided by dentist practitioner-investigators in The Dental Practice-Based Research Network (DPBRN). DPBRN has a wide representation of practice types, treatment philosophies, and patient populations, including diversity with regard to the race, ethnicity, socio-economic status, geography and rural/urban area of residence of both its practitioner-investigators and their patients (Makhija et al., accepted; Makhija et al., under review). The specific aims of this study were to: (1) identify and profile the types of treatment that dentists in general dental practice use to manage defective dental restorations; and (2) identify characteristics that are associated with variation in these dentists’ decisions to replace existing restorations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The cross-sectional study design employed a single administration of a questionnaire to all DPBRN dentist practitioner-investigators who indicated on their DPBRN Enrollment Questionnaire that they do at least some restorative dentistry in their practices (n=901). The study was approved by the respective Institutional Review Board (IRB) of all participating regions. As part of enrollment in DPBRN, all practitioner-investigators complete an Enrollment Questionnaire about their practice characteristics and themselves. This questionnaire and other details about DPBRN are publicly available at http://www.DentalPBRN.org. and www.dentalpbrn.org/users/related_links/default.asp.

This report provides results from certain questions (clinical case scenarios including photographs of existing restorations) from the DPBRN “Assessment of Caries Diagnosis and Treatment” questionnaire. The full questionnaire, which comprised DPBRN’s first study to involve all five DPBRN regions (“Study 1”), is publicly available at http://www.dentalpbrn.org/users/publications/Supplement.aspx. Methodologic particulars, such as sample selection, the recruitment process, the length of the field phase, the data collection process, and the procedures used during the pilot study and pre-testing of the questionnaire have been previously reported (Gordan et al., manuscript submitted).

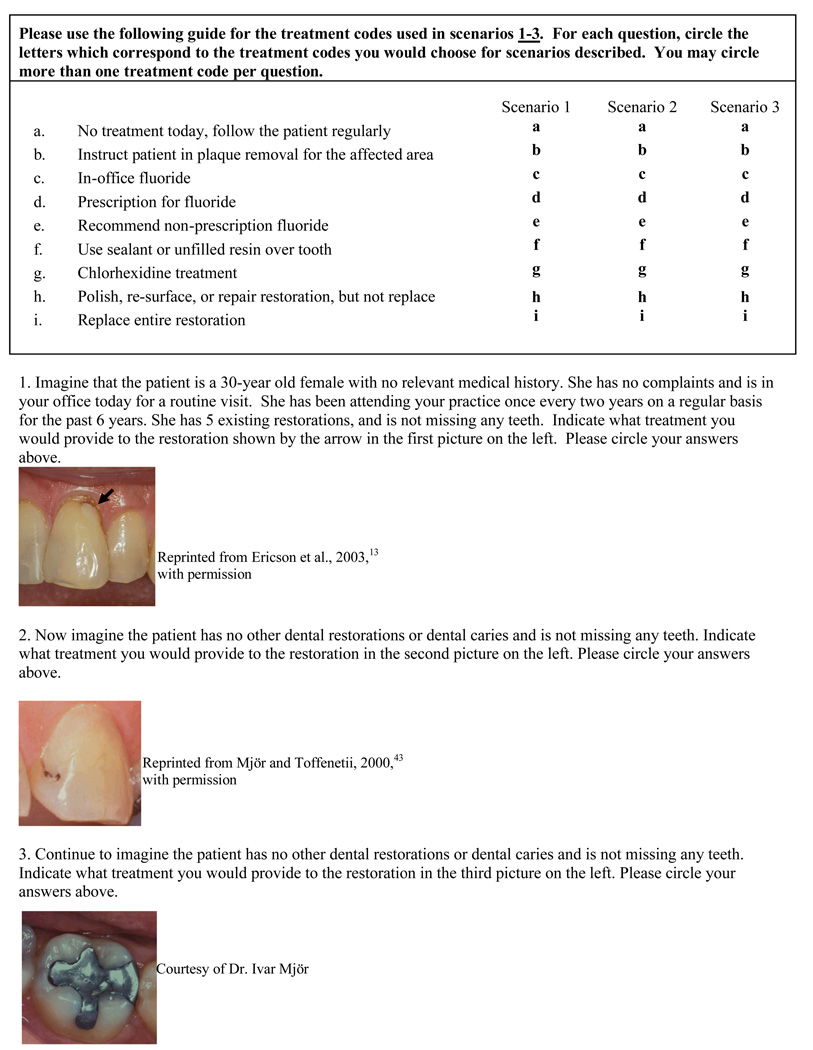

Questions referred to dentists’ assessments of observations of high-resolution photographs of various defective restorations accompanied by case descriptions (Figure 1). The first case had a defective composite restoration with cementum-dentinal margins and a description of a patient who had been a regular dental patient and had existing dental restorations (Figure 1). A second case had a defective composite restoration with enamel margins and a description of a patient at low caries risk (Figure 1). A third case had a defective amalgam restoration and a description of the same patient at low caries risk. Dentists were asked what type of treatments they deemed appropriate. The nine treatment options provided (Figure 1, treatment options “a through i”) varied from no treatment to replacement of the entire restoration. Options “a through i” also included different preventive options. In a different part of the questionnaire, dentists were also asked about assessment of caries risk (“Do you assess caries risk for individual patients in any way?”).

Figure 1.

Scenarios asked of participating dentists:

We categorized these nine treatment options into three categories: (1) no treatment; (2) preventive treatment only; and (3) any sort of surgical intervention (Table 1). We divided the “surgical intervention” category into four sub-categories: (1) minimally-invasive intervention only; (2) minimally-invasive intervention and preventive treatment; (2) replacement of the entire restoration only; and (4) replacement of the entire restoration and preventive treatment (Table 1).

Table 1.

The treatment options provided in Scenarios 1 through 3

| Treatment Option | Treatment Description |

|---|---|

| No treatment | No treatment should be delivered |

| Preventive treatment only | Patient instruction on plaque removal, in-office fluoride, prescription of fluoride, non-prescription fluoride, chlorhexidine treatment |

| Surgical intervention | Minimally-invasive intervention only, done by either 1) polishing the restoration; 2) re-surfacing the restoration with a sealant; or 3) repairing the restoration but not replacing it entirely. |

| Minimally-invasive intervention treatment and preventive treatment | |

| Replace the entire restoration only, done with either 1) amalgam; 2) composite; or 3) indirect restoration | |

| Replace the entire restoration and preventive treatment |

Study Population

This study queried dentists participating in DPBRN, which comprises outpatient dental practices that have affiliated to investigate research questions and to share experiences and expertise. DPBRN comprises five regions: AL/MS: Alabama/Mississippi, FL/GA: Florida/Georgia, MN: dentists employed by HealthPartners and private practitioners in Minnesota, PDA: Permanente Dental Associates in cooperation with Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research, and SK: Denmark, Norway, and Sweden (Gilbert et al., JADA 2008). DPBRN dentist practitioner-investigators were recruited through continuing education courses and mass mailings to licensed dentists within the participating regions.

DPBRN dentists can also be characterized by “type of practice”, for which we categorized each dentist as being in either: (1) a solo or small group private practice (SPP); (2) a large group practice (LGP); or (3) a public health practice (PHP). “Small” practices were defined as those that had 3 or fewer dentists. Public health practices were defined as those that receive the majority of their funding from public sources.

Analyses of the characteristics of DPBRN dentists and their practice characteristics suggest that DPBRN dentists have much in common with dentists at large (Makhija et al 2008; accepted for publication), while at the same time offering substantial diversity in terms of the characteristics (Makhija et al; manuscript under review).

Variable Selection

Potential explanatory variables for dentists’ decisions to treat defective restorations were identified based on extant literature related to theoretical models of factors associated with dentists’ treatment decisions (Bader and Shugars, 1997) and dental practice characteristics (Gilbert et al, 2006; Gilbert et al., 2008). The explanatory variables included during bivariate analyses are listed in Table 2 and included measures of: (1) dentist’s individual characteristics (namely, year of graduation from dental school, race/ethnicity, and gender); (2) practice setting (namely, practice busyness, waiting time for a restorative dentistry appointment, DPBRN region and type of practice); (3) patient population (namely, dental insurance coverage, number of patients who self-pay (pay out of their own resources), age distribution, and racial/ethnic distribution); and (4) dental procedure characteristics (namely, percent of patient contact spent each day doing restorative work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing extractions, and whether or not caries risk is done as a routine part of treatment planning).

Table 2.

Dental practice characteristics tested for their association with the treatment options chosen by DPBRN practitioner-investigators

| Dentist’s Individual Characteristics |

Practice Setting | Patient Population | Dental Procedure Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year since graduation from dental school |

Practice busynessa | Dental insurance coverage |

Percent of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative workc |

| Race/ ethnicity | Waiting time for restorative dentistry |

Number of patients who self-pay (pay out of their own resources) |

Percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic workc |

| Gender | DPBRN region of practice |

Age distribution | Percent of patient contact time spent each day doing extractionsd |

| Type of practiceb | Racial/ethnic distribution |

Whether or not caries risk is done as a routine part of treatment planning |

a= 1=too busy to treat all people requesting appointments, 2=provided care to all who requested appointments, but the practice was overburdened; 3= provided care to all who requested appointments, and the practice was not overburdened; 4= not busy enough-the practice could have treated more patients

b= 1=solo or small group private practice; 2=large group practice; 3=public health practice

c=0=none; 1=1–30% of the time; 2=31 to 50% of the time; 3=more than 50% of the time.

d= 0=none; 1=1–20% of the time; 2=21 to 30% of the time; 3=more than 30% of the time.

Additionally a logistic regression model was tested which included: practice busyness, type of practice, number of patients who self-pay, age distribution of patients, percent of patient contact spent each day doing restorative work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing extractions, and whether or not caries risk is done as a routine part of treatment planning. The race/ethnicity of dentist was not used in analysis because of small cell sizes.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS software version 9.1 (Cary, N.C.). A p-value of .05 or less was considered statistically significant. Bivariate analyses examined associations between the explanatory variables and treatment decisions. Chi-square tests were used for bivariate analysis when explanatory variables were categorical. ANOVA and multiple comparison tests were used when explanatory variables were continuous.

RESULTS

Questionnaires were mailed to 901 dentists and 512 (57%) were completed and returned. Not all dentists responded to all questions, therefore, the sample size in each response differs in some instances.

Table 3 through Table 5 report the clinical treatment options chosen, by dentists’ and practice characteristics. For all 3 scenarios, dentists participating in solo or small group private practice (SPP) chose the replacement of the entire restoration more often than dentists who participate in large group practices (LGP) or public health practices (PHP) (p<.0001). For all three case scenarios, dentists in PHP chose the “no treatment” option more often than dentists in SPP or LGP, and dentists in LGP were the most likely to recommend prevention alone or in combination with other treatments (p<.0001). Also common to all three case scenarios, dentists who did not assess caries risk as part of treatment planning were most likely to choose one of the surgical treatment options and less likely to choose the prevention treatment (p<.05).

Table 3.

Treatment options chosen by DPBRN practitioner-investigators when evaluating an existing composite restoration that interfaces with a dentin surface (scenario 1), by dentist and practice characteristics

| N=512 | No treatment |

Preventive treatment only |

Minimally- invasive intervention only |

Replace the entire restoration only |

Minimally- invasive intervention and preventive |

Replace the entire restoration and preventive |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years since graduation from dental school Mean (SD) |

23.3 (10.3) | 20.7 (8.2) | 21.4 (10.3) | 19.7 (11.2) | 19.0 (11.3) | 19.3 (9.4) | .2280 |

| Gender of dentist | .016 * | ||||||

| Male (422) | 9% | 4% | 9% | 36% | 10% | 32% | |

| Female (90) | 11% | 3% | 10% | 19% | 20% | 37% | |

| Region | <.0001 * | ||||||

| AL/MS (296) | 6% | 2% | 8% | 43% | 9% | 32% | |

| FL/GA (99) | 7% | 2% | 17% | 27% | 7% | 40% | |

| MN (30) | 3% | 7% | 10% | 23% | 20% | 37% | |

| PDA (50) | 10% | 6% | 8% | 8% | 32% | 36% | |

| SK (37) | 43% | 16% | 8% | 8% | 22% | 3% | |

| Type of practice | <.0001 * | ||||||

| SPP (415) | 9% | 3% | 11% | 37% | 7% | 33% | |

| LGP (77) | 8% | 6% | 8% | 13% | 29% | 36% | |

| PHP (20) | 20% | 20% | 5% | 10% | 35% | 10% | |

| Number of patients who self-pay (pay out of their own resources) |

.0003 * | ||||||

| 14% | 21% | 0% | 0% | 22% | 43% | ||

| 0 % (14) | 7% | 3% | 11% | 35% | 14% | 30% | |

| 1–30% (239) | 6% | 3% | 9% | 37% | 7% | 38% | |

| 31–50% (126) | 18% | 4% | 12% | 27% | 9% | 30% | |

| >51% (108) | |||||||

| Whether or not caries risk is done as a routine part of treatment planning |

.02 * | ||||||

| Yes (357) | 10% | 4% | 10% | 30% | 14% | 32% | |

| No (133) | 8% | 4% | 10% | 43% | 5% | 30% |

statistical significance

Bivariate analyses were conducted on the following explanatory variables: practice busyness, waiting time for restorative treatment, patients dental insurance coverage, age and racial/ethnic distribution of patients seen in the practice, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing extractions. None of the variables were significant. Additionally, logistic regression analyses were done for both outcomes, which included the following explanatory variables: dentist’s year since graduation from dental school and gender, practice busyness, type of practice, age distribution of patients, number of patients who self-pay (pay out of their own resources), percent of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing extractions, and whether or not caries risk is done as a routine part of treatment planning. The results of the logistic regression did not differed from those found in the bivariate analyses.

Table 5.

Treatment options chosen by DPBRN practitioner-investigators when evaluating an existing amalgam restoration that interfaces with an enamel surface (scenario 3), by dentist and practice characteristics

| N=494 | No treatment |

Preventive treatment only |

Minimally- invasive intervention only |

Replace the entire restoration only |

Minimally- invasive intervention and preventive |

Replace the entire restoration and preventive |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years since graduation from dental school Mean (SD) |

20.7 (10.0) | 12.1 (9.6) | 18.7 (10.2) | 20.5 (10.9) | 15.9 (9.9) | 20.9 (11.4) | .0052* |

| Gender of dentist | .482 | ||||||

| Male (407) | 51% | 4% | 6% | 30% | 4% | 5% | |

| Female (87) | 55% | 5% | 5% | 24% | 2% | 9% | |

| Region | <.0001* | ||||||

| AL/MS (282) | 53% | 2% | 4% | 32% | 3% | 6% | |

| FL/GA (97) | 46% | 0% | 8% | 36% | 3% | 7% | |

| MN (29) | 62% | 11% | 7% | 10% | 3% | 7% | |

| PDA (51) | 43% | 20% | 11% | 12% | 10% | 4% | |

| SK (35) | 62% | 3% | 9% | 23% | 0% | 3% | |

| Type of practice | <.0001* | ||||||

| SPP (399) | 52% | 1% | 6% | 33% | 2% | 6% | |

| LGP (76) | 53% | 17% | 9% | 9% | 8% | 4% | |

| PHP (19) | 58% | 5% | 5% | 16% | 16% | 0% | |

| Number of patients who self-pay (pay out of their own resources) |

.173 | ||||||

| 71% | 14% | 0% | 15% | 0% | 0% | ||

| 0 % (14) | 55% | 6% | 6% | 23% | 4% | 6% | |

| 1–30% (231) | 47% | 3% | 6% | 36% | 3% | 5% | |

| 31–50% (120) | 53% | 1% | 5% | 31% | 3% | 7% | |

| >51% (104) | |||||||

| Whether or not caries risk is done as a routine part of treatment planning |

.02 * | ||||||

| 57% | 1% | 6% | 31% | 0% | 5% | ||

| 50% | 6% | 6% | 28% | 5% | 5% | ||

| Yes (344) | |||||||

| No (128) |

statistical significance

Bivariate analyses were conducted on the following explanatory variables: practice busyness, waiting time for restorative treatment, patients dental insurance coverage, age and racial/ethnic distribution of patients seen in the practice, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing extractions. None of the variables were significant. Additionally, logistic regression analyses were done for both outcomes, which included the following explanatory variables: dentist’s year since graduation from dental school and gender, practice busyness, type of practice, age distribution of patients, number of patients who self-pay (pay out of their own resources), percent of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing extractions, and whether or not caries risk is done as a routine part of treatment planning. The results of the logistic regression did not differed from those found in the bivariate analyses.

For the first case scenario, Table 3 shows that male dentists chose the “replace the entire restoration” option more often than female dentists (p=.016). Also for the first case scenario, dentists participating in practices that have a high percent of patients who “self-pay” chose “surgical intervention” options less often and the prevention treatment more often (p=.0003). For both the first and second case scenarios, dentists from the SK region chose the “no treatment” option more often than dentists from the AL/MS, FL/GA, MN, and PDA regions (p<.0001).

Table 5 shows that for the third case scenario, dentists from the AL/MS and FL/GA regions chose the “replace the entire restoration” option more often than dentists from the MN, PDA, and SK regions (p<.0001). Also for the third case scenario, dentists with fewer years since graduation were more likely to have recommended preventive treatment than those with more years since graduation (p=.0052).

Table 6 summarizes the distribution of treatment options chosen by all participating dentists for each clinical case scenario. Differences were found for the type of restorative material used on the existing restoration (composite versus amalgam) and the type of margin where the composite restoration was located (enamel versus dentinal margins). In general, dentists elected to replace the composite restoration with margin located on dentin (65%), to repair the composite restoration with margin located on enamel (49%), and not to treat the amalgam restoration (52%).

Table 6.

Distribution of treatment options chosen by DPBRN practitioner-investigators for scenarios 1 through 3.

| Treatment option chosen |

Scenario 1 (n=512) |

Scenario 2 (n=509) |

Scenario 3 (n=494) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No treatment | 9% | 10% | 52% |

| Preventive treatment only |

4% | 6% | 4% |

| Surgical intervention* | 87% | 84% | 44% |

| Sub-categories of surgical intervention |

|||

| Minimally-invasive intervention only |

10% | 34% | 6% |

| Minimally-invasive intervention with preventive treatment |

12% | 15% | 3% |

| Replace the entire restoration only |

33% | 24% | 29% |

| Replace the entire restoration with preventive treatment |

32% | 11% | 6% |

The area highlighted in gray shows a breakdown of the surgical intervention treatment option.

DISCUSSION

Comparisons of recommendations made for treatment of existing restorations have shown remarkable differences among dentists (Rytomaa at al., 1979; Merrett and Elderton, 1984; Kay et al., 1988; Noar and Smith, 1990; Bader et al., 1994 Bader and Shugars, 1993). Findings from our current study corroborate these significant differences among dentists, but also add to the literature by being able to compare and contrast these treatment recommendations by key dentist and practice characteristics.

The most prominent difference regarding the type of treatment chosen is related to the type of practice. Dentists participating in solo or small group private practice in the U.S. chose the surgical intervention option more often than dentists who participate in large group practices or public health practices. In solo or small group private practices, practice revenues and costs are directly linked to procedures being done, and amount of time used to deliver care. Because of the capitation model, dentists participating in this type of practices may feel the need to choose the surgical intervention option more often. Although dentists in large group practices or public health practices may have production or revenue incentives, this is not their main source of income. Therefore, participants in these types of practice may feel less pressured to recommend services that have higher fees. Additionally, dentists participating in large group practices might be under an organization in which standardization of diagnosis and treatment of recurrent caries might be more available and consistent. In fact, the HealthPartners Dental Group has a manual for caries treatment that standardizes how dental caries is diagnosed clinically. The Permanente Dental Associates group of dentists also seeks to standardize treatment recommendations among its dentists by having a Clinical Effectiveness Committee, composed of dentists from each clinic who reviews evidence and sets practice standards.

DPBRN dentists who practice in non-fee for service settings chose preventive treatment more often than surgical intervention. This finding is consistent with a study of North Carolina dentists which reported that dentists involved in pediatric practices with high volume of patients under public insurance had positive opinions about their practice and assessed risk factors in their patients (dela Cruz, 2004). Additionally, the dentists who assessed caries risk had a more conservative restorative treatment approach. Similarly, in our current study, dentists who assessed caries risk as part of routine treatment planning were most likely to choose the “no treatment” and preventive treatment options.

Dentists from the DPBRN Scandinavia region chose the “no treatment” option more often than the DPBRN United States dentists. Previous studies have shown that dentists in Scandinavia are more likely to recommend non-surgical dental treatment (Lith et al., 1995; Lith et al., 2002). Current treatment strategy in Scandinavia is based on the dentist’s assessment of patients’ caries risk (Lagerlof and Oliveby, 1996). In contrast, in North American dental schools this concept was introduced only during the past decade (Ismail, 1997; Lundeen and Roberson, 1995). Furthermore, Scandinavian dental practices typically use restrictive criteria for intervention (Mjör et al., 2008). Additionally, the patient population of the Scandinavian region is substantially different from the United States patient population (Holm-Pedersen et al., 2005; Helöe, 1991; Gordon and Newbrun, 1986). Dental care in Scandinavia is mainly subsidized by the government and, as a result, patients receive regular dental care. Additionally, dental care for children is provided in school-based clinics that can readily set an expectation for regular visits. The expectation for socialized regular care during childhood leads to better compliance with dentists’ recommendation during adulthood, so Scandinavian dentists may be more comfortable with monitoring restorations that deviate from ideal, instead of intervening surgically. In fact, the Norwegian Public Oral Health Act of 1983 (http://www.lovdata.no/all/nl-19830603-054.htm) states that prevention must be attempted before treatment.

DPBRN practitioner-investigators were less likely to intervene surgically in the amalgam restoration scenario, as compared to the composite restoration scenarios. This behavior is consistent with evidence from the literature that suggests that there is a poor correlation between the presence of defective margins and caries after removal of amalgam restorations (Maryniuk and Brunson, 1989). Additionally, amalgam has been used in dentistry for over 150 years and various studies report on its superior longevity when compared to composite restorations (Soncini et al., 2007; Bernardo et al., 2008).

In our current study, dentists with fewer years since graduation from dental school recommended more prevention for the defective amalgam restoration scenario. The transition from intervention to prevention in caries treatment has been a slow process. Within the last 10 years, dental school programs have attempted to incorporate various levels of disease control (Clark and Mjör, 2001). Also a more defined role for caries diagnosis and prevention has recently been introduced (Ismail, 1997; Lundeen and Roberson, 1995) in North American textbooks of operative dentistry. Therefore, despite the slow translation of research findings to dental school programs, recently-graduated clinicians seemed to have been given some exposure to these subjects.

Some dentists in the current study recommended complete replacement of restorations with defective margins. The lack of standards to determine restoration failure may cause the dentists to favor surgical intervention when faced with uncertainty about whether an appropriate diagnostic threshold has been reached. For example, many textbooks of operative dentistry or cariology do not differentiate whether recurrent caries lesions are active or arrested carious lesions, and this differentiation is often not included in diagnosis and treatment planning (Clark and Mjör, 2001; Yorty and Brown, 1999). This preference for surgical intervention may also be the result of a complex interplay between the lack of clear standards for replacing restorations and lack of an existing reimbursement for these treatments. For composite restorations, dentists’ recommendations in these clinical scenarios may be substantially affected by the esthetic demands of the particular patient population that they care for on a regular basis.

Most dentists chose not to replace the entire restoration where the discoloration/defect was at the enamel margin (scenario 2) as compared to entire replacement when a dentin/cementum margin was affected (scenario 1). Recurrent caries in composite restorations does occur more frequently at the cervical area (Mjör, 1985), and this may explain the tendency of most dentists to opt for replacement of the entire composite restoration that involved margins in dentin or cementum. Although the patients in both scenarios 1 and 2 were of the same characteristics with regard to age, gender, dental visitation behavior, missing teeth, and no other active caries, the patient in scenario 1 did have five existing restorations, while the patient in scenario 2 had no restorations other than the one being considered; therefore, some practitioner-investigators may have concluded that the patient in scenario 2 was at lower risk for caries.

CONCLUSIONS

Treatment options chosen by DPBRN dentists differed according to the specific case scenario, whether or not they caries risk as a routine part of treatment planning, type of practice and DPBRN region.

Dentists were more likely to intervene surgically on existing composite restorations than they were on existing amalgam restoration.

Dentists who did not assess caries risk as a routine part of the treatment planning process were more likely to choose a surgical intervention and less likely to choose preventive treatment.

Dentists participating in solo or small group private practice were more likely to recommend surgical intervention as compared to dentists who participate in large group practices or public health practices.

Table 4.

Treatment options chosen by DPBRN practitioner-investigators when evaluating an existing composite restoration that interfaces with an enamel surface (scenario 2), by dentist and practice characteriics

| N=509 | No treatment |

Preventive treatment only |

Minimally- invasive intervention only |

Replace the entire restoration only |

Minimally- invasive intervention and preventive |

Replace the entire restoration and preventive |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years since graduation from dental school Mean (SD) |

19.9 (10.5) | 20.0 (8.6) | 20.5 (9.5) | 20.9 (11.5) | 18.0 (10.0) | 19.2 (10.8) | .4898 |

| Gender of dentist | .08 | ||||||

| Male (420) | 10% | 5% | 35% | 25% | 14% | 11% | |

| Female (89) | 11% | 10% | 29% | 18% | 23% | 9% | |

| Region | <.0001 * | ||||||

| AL/MS (292) | 7% | 5% | 32% | 32% | 12% | 12% | |

| FL/GA (99) | 11% | 4% | 41% | 21% | 11% | 12% | |

| MN (31) | 13% | 17% | 35% | 6% | 26% | 3% | |

| PDA (51) | 8% | 8% | 29% | 0% | 43% | 12% | |

| SK (36) | 31% | 7% | 42% | 14% | 3% | 3% | |

| Type of practice | <.0001 * | ||||||

| SPP (412) | 9% | 5% | 34% | 30% | 11% | 11% | |

| LGP (78) | 9% | 10% | 32% | 1% | 39% | 9% | |

| PHP (19) | 32% | 5% | 37% | 5% | 16% | 5% | |

| Number of patients who self-pay (pay out of their own resources) |

.106 | ||||||

| 14% | 22% | 36% | 0% | 21% | 8% | ||

| 0 % (14) | 9% | 5% | 31% | 26% | 19% | 10% | |

| 1–30% (235) | 9% | 5% | 37% | 27% | 9% | 13% | |

| 31–50% (126) | 15% | 4% | 36% | 23% | 13% | 9% | |

| >51% (109) | |||||||

| Whether or not caries risk is done as a routine part of treatment planning |

.001 * | ||||||

| 11% | 6% | 35% | 20% | 16% | 12% | ||

| 8% | 4% | 34% | 37% | 11% | 6% | ||

| Yes (354) | |||||||

| No (132) |

statistical significance

Bivariate analyses were conducted on the following explanatory variables: practice busyness, waiting time for restorative treatment, patients dental insurance coverage, age and racial/ethnic distribution of patients seen in the practice, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing extractions. None of the variables were significant. Additionally, logistic regression analyses were done for both outcomes, which included the following explanatory variables: dentist’s year since graduation from dental school and gender, practice busyness, type of practice, age distribution of patients, number of patients who self-pay (pay out of their own resources), percent of patient contact time spent each day doing restorative work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing esthetic work, percent of patient contact time spent each day doing extractions, and whether or not caries risk is done as a routine part of treatment planning. The results of the logistic regression did not differed from those found in the bivariate analyses.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Ivar Mjör, who served as a consultant during the planning phase of the research project, and all DPBRN practitioner-investigators who responded to the questionnaire. Furthermore, the authors would like to acknowledge grants U01-DE-16746 and U01-DE-16747 from NIDCR-NIH. The DPBRN Collaborative Group comprises practitioner-investigators, faculty investigators, and research staff who contributed to this DPBRN activity. A list of these names is provided at http://www.dpbrn.org/users/publications/Default.aspx.

Contributor Information

Valeria V Gordan, College of Dentistry, Department of Operative Dentistry at University of Florida.

Cynthia W Garvan, College of Education, University of Florida.

Joshua S Richman, Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Jeffrey L Fellows, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, Oregon.

D. Brad Rindal, HealthPartners, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Vibeke Qvist, Department of Cariology and Endodontics, School of Dentistry, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Copenhagen.

Marc W. Heft, College of Dentistry, Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery and Oral Diagnostic Sciences, at University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida, USA.

O Dale Williams, Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Gregg H Gilbert, Department of Diagnostic Sciences, College of Dentistry, University of Alabama at Birmingham.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mjör IA, Shen C, Eliasson ST, Richter S. Placement and replacement of restorations in general dental practice in Iceland. Oper Dent. 2002;27:117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernardo M, Luis H, Martin MD, Leroux BG, Rue T, Leitao J, DeRouen TA. Survival and reasons for failure of amalgam versus composite posterior restorations placed in a randomized clinical trial. JADA. 2007;138:775–783. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mjör I. Amalgam and composite resin restorations: longevity and reasons for replacement. In: Anusavice KJ, editor. Quality evaluation of dental restorations. Chicago: Quintessence; 1989. pp. 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qvist J, Qvist V, Mjör IA. Placement and longevity of amalgam restorations in Denmark. Acta Odontol Scand. 1990;48:297–303. doi: 10.3109/00016359009033620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qvist V, Qvist J, Mjör IA. Placement and longevity of tooth colored restorations in Denmark. Acta Odontol Scand. 1990;48:305–311. doi: 10.3109/00016359009033621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ericson D, Kidd E, McComb D, Mjor IA, Noack MJ. Minimally invasive dentistry- Concepts and techniques in Cariology. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2003;1:59–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braga SR, Vasconcelos BT, Macedo MR, Martins VR, Sobral MA. Reasons for placement and replacement of direct restorative materials in Brazil. Quintessence Int. 2007;38:189–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kidd EAM. Caries diagnosis within restored teeth. In: Anusavice KJ, editor. Quality evaluation of dental restorations. Chicago: Quintessence; 1989. pp. 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Public health and aging: retention of natural teeth among older adults- United States, 2002. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;19:1226–1229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tyas MJ. Cariostatic effect of glass ionomer cement: a five-year clinical study. Aust Dent J. 1991;36:236–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1991.tb04710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ismail AI. Clinical diagnosis of precavitated carious lesions. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:13–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brantley CF, Bader JD, Shugars DA, Nesbit SP. Does the cycle of rerestoration lead to larger restorations? JADA. 1995;126:1407–1413. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1995.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordan VV. In vitro evaluation of margins of replaced resin based composite restorations. J Esthet Dent. 2000;12:217–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2000.tb00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordan VV. Clinical evaluation of replacement of class v resin based composite restorations. J Dent. 2001;29:485–488. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(01)00030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gordan VV, Mondragon E, Shen C. Evaluation of the cavity design, cavity depth, and shade matching in the replacement of resin based composite restorations. Quintessence Inter. 2002;32:273–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elderton RJ, Nuttall NM. Variation among dentists in planning treatment. Br Dent J. 1983;154:201–206. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4805041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bader JD, Shugars DA. Understanding dentists’ restorative treatment decisions. J Public Health Dent. 1992;52:102–110. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.1992.tb02251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, Benjamin PL, Richman JS, Pihlstrom DJ, Qvist V for the DPBRN Collaborative Group. Dentists in practice-based research networks have much in common with dentists at large: evidence from The Dental PBRN. Gen Dent. 2008 accepted for publication. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makhija SK, Gilbert GH, Rindal DB, Benjamin PL, Richman JS, Pihlstrom DJ, Qvist V for the DPBRN Collaborative Group. Practices participating in a dental PBRN have substantial and advantageous diversity even though as a group they have much in common with dentists at large. Manuscript under review at the Journal of the American Dental Association. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-9-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordan VV, Bader JD, Garvan CW, Richman J, Qvist V, Fellows JL, Rindal DB, Gilbert GH and for The DPBRN Collaborative Group. Restorative Treatment Thresholds for Primary Caries by Dental PBRN Dentists. JADA. Accepted in 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilbert GH, Williams OD, Rindal DB, Pihlstrom DJ, Benjamin PL, Wallace MA for the DPBRN Collaborative Group. The creation and development of The Dental Practice-Based Research Network. JADA. 2008;139:74–81. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bader JD, Shugars DA. What do we know about how dentists make caries-related treatment decisions? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25(1):97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1997.tb00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilbert GH, Bader JD, Litaker MS, Shelton BJ, Duncan RP. Patient-level and practice level characteristics associated with receipt of preventive dental services: 48-month incidence. J Public Health Dent. 2008;68:209–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2007.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilbert GH, Shewchuk RM, Litaker MS. Effect of dental practice characteristics on racial disparities in patient-specific tooth loss. Med Care. 2006;44:414–420. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000207491.28719.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rytomaa I, Jarvinen V, Jarvinen J. Variation in caries recording and restorative treatment plan among university teachers. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1979;7:335–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1979.tb01243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merrett MCW, Elderton RJ. An vitro study of restorative dental treatment decisions and dental caries. Br Dent J. 1984;157:128–133. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4805448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kay E, Watts A, Paterson R, Blinkhorn A. Preliminary investigation into the validity of dentists’ decisions to restore occlusal surfaces of permanent teeth. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1988;16:91–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1988.tb01850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noar SJ, Smith BGN. Diagnosis of caries and treatment decisions in approximal surfaces of posterior teeth in vitro. J Oral Rehabil. 1990;17:209–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.1990.tb00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bader JD, Shugars DA, McClure FE. Comparison of restorative treatment recommendations based on patients and patients simulations. Oper Dent. 1994;19:20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bader JD, Shugars DA. Agreement among dentists’ recommendations for restorative treatment. J Dent Res. 1993;72:891–896. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720051001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.dela Cruz GG, Rozier RG, Slade G. Dental screening and referral of young children by pediatric primary case providers. Pediatrics. 2004;114:642–652. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lith A, Pettersson LG, Gröndahl HG. Radiographic study of approximal restorative treatment in children and adolescents in two Swedish communities differing in caries prevalence. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1995 Aug;23(4):211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1995.tb00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lith A, Lindstrand C, Gröndahl HG. Caries development in a young population managed by a restrictive attitude to radiography and operative intervention: II. A study at the surface level. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2002 Jul;31(4):232–239. doi: 10.1038/sj.dmfr.4600705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lagerlöf F, Oliveby A. Clinical implications: new strategies for caries treatment. In: Stookey GK, editor. Early detection of dental caries. Indianapolis, IN: School of Dentistry, Indiana University; 1996. pp. 297–316. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundeen TF, Roberson TM. Cariology: the lesion, etiology, prevention, and control. In: Sturdevant CM, Roberson TM, Heymann HO, Sturdevant JR, editors. The Art and Science of Operative Dentistry. St Louis, Missouri: Mosby; 1995. pp. 60–128. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mjör IA, Holst D, Eriksen HM. Caries and restoration prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008 May;139(5):565–570. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0216. quiz 626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holm-Pedersen P, Vigild M, Nitschke I, Berkey DB. Dental care for aging populations in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, United Kingdon, and Germany. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:987–997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helöe LA. Comparative policies of two national dental associations: Norway and the United States. J Public Health Policy. 1991;12:209–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gordon M, Newbrun E. Comparison of trends in the prevalence of caries and restorations in young adult populations of several countries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1986;14:104–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1986.tb01507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Maryniuk GA, Brunson WD. When to replace faulty-margin amalgam restorations: a pilot study. Gen Dent. 1989;37:463–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soncini JA, Maserejian NN, Trachtenberg F, Tavares M, Hayes C. The longevity of amalgam versus compomer/composute restorations in posterior primary and permanent teeth: findings from the New England Children’s Amalgam Trial. JADA. 2007;138:763–772. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2007.0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clark TD, Mjör IA. Current teaching of cariology in North American dental schools. Oper Dent. 2001;26:412–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yorty JS, Brown KB. Caries risk assessment/treatment programs in US dental schools. J Dent Educ. 1999;63:745–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mjor IA. Frequency of secondary caries at various anatomical locations. Oper Dent. 1985 Summer;10(3):88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]