Abstract

Oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) remains a common problem in the HIV-infected population despite the availability of antiretroviral therapy (ART). Although Candida albicans is the most frequently implicated pathogen, other Candida spp. may also cause infection. The emergence of antifungal resistance within these causative yeasts, especially in patients with recurrent oropharyngeal infection or with long-term use of antifungal therapies, requires a working knowledge of alternative antifungal agents. Identification of the infecting organism and antifungal susceptibility testing enhances the ability of clinicians to prescribe appropriate antifungal therapy. Characterization of the responsible mechanisms has improved our understanding of the development of antifungal resistance and could enhance the management of these infections. Immune reconstitution has been shown to reduce rates of oropharyngeal candidiasis but few studies have evaluated the current impact of ART on the epidemiology of oropharyngeal candidiasis and antifungal resistance in these patients. Preliminary results from an ongoing clinical study showed that in patients with advanced AIDS oral yeast colonization was extensive, occurring in 81.1% of the 122 patients studied and symptomatic infection occurred in a third. In addition, resistant yeasts were still common occurring in 25.3% of patients colonized with yeasts or with symptomatic infection. Thus, oropharyngeal candidasis remains a significant infection in advanced AIDS even with ART. Current knowledge of the epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, treatment, and mechanisms of antifungal resistance observed in oropharyngeal candidiasis are important in managing patients with this infection and are the focus of this review.

Keywords: thrush, OPC, oral candidiasis, Candida, resistance

INTRODUCTION

Oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC), or thrush, is a common and localized infection typically caused by the yeast Candida albicans, a normal component of the human gastrointestinal microflora. While the incidence of OPC has declined for HIV-infected persons with access to antiretroviral therapy (ART)1–3, it remains a significant problem for those in resource-limited settings or those with a poor immunologic response despite the initiation of ART4. Oropharyngeal candidiasis may also be an early indicator of HIV infection and may predict progressive immunodeficiency5.

This manifestation of underlying immunosuppression was seen in up to 90% of at risk individuals infected with HIV prior to the availability of ART6. OPC is typically managed with oral fluconazole and further attempts to improve patient’s ability to mount an effective immunologic response7. However, mycological resistance, which is most commonly found in the setting of advanced HIV with extensive prior triazole use continues to occur8, 9. Fluconazole failure, while less frequent than prior to the widespread availability of ART, remains difficult to manage in patients with advanced immunodeficiency 10, 11.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Prior to the availability of active antiretroviral therapy, oropharyngeal candidiasis was a very common finding in patients with HIV/AIDS. With the development of effective antiretroviral drugs, rates of oral candidiasis were reported to decrease1–3. Declining rates of oropharyngeal candidiasis and carriage of C. albicans were associated with trends toward reduced rates of carriage of fluconazole-resistant C. albicans in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients12. The epidemiology of oral candidiasis in patients receiving antiretroviral therapy and the significance of antifungal resistance in this population is not well-described. In preliminary results reported at the 48th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy we described oral yeast colonization and infection from an ongoing clinical trial in patients with advanced HIV infection. In that report, we evaluated the presence of symptomatic oral candidiasis or asymptomatic yeast colonization. We found 99/122 (81.1%) of patients were colonized by oral yeasts and thirty-three of these patients (33.3%) had symptomatic infection. Fluconazole resistant yeasts were frequently isolated even in the setting of ART, with detection in 25/99 (25.3%) patients13.

Candida albicans is responsible for the majority of OPC episodes. However other species such as C. glabrata, C. krusei, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, and C. dublinensis have also often been implicated, particularly in patients with advanced HIV/AIDS before the availability of active antiretroviral therapy, but also in other populations including patients undergoing bone marrow transplantation and in patients receiving therapy for head and neck cancer11, 14–16.

These pathogens warrant discussion due to their potential to harbor antifungal resistance mechanisms. Results of our recent clinical data show that while C. albicans remains the most common etiological agent in patients with advanced AIDS (54% of isolates) C. dublinensis (17%) and C. glabrata (16%) are the second and third most frequently isolated species (Table 1). Both of these latter two organisms may exhibit decreased susceptibility or frank resistance to fluconazole so that recognition of these important causes of OPC may aid the clinician in cases recalcitrant to fluconazole therapy.

TABLE 1.

Candida spp. isolated from 122 consecutive HIV-infected patients upon enrollment to our longitudinal OPC study (includes patients with thrush and those colonized).

| Candida spp. | No. of isolates (%) |

|---|---|

| C. albicans | 110 (54) |

| C. dublinensis | 35 (17) |

| C. glabrata | 32 (16) |

| C. tropicalis | 12 (6) |

| C. krusei | 7 (3) |

| C. parapsilosis | 5 (2) |

| C. lusitaniae | 2 (1) |

| C. guillermondii | 1 (0.5) |

| S. cerevisiae | 1 (0.5) |

Additionally, previous antifungal treatment regimens have had a significant impact on the development of resistance17. The use of repeated or suppressive courses of low-dose fluconazole (50–100 mg/day) has contributed to the development of fluconazole resistant C. albicans as well as other intrinsically resistant yeasts such as C. krusei and C. glabrata17. In fact, other reports have identified C. glabrata as the second most common cause of OPC, with C. krusei third, although C. krusei was the fifth most common isolate in our study18. To combat the emergence of these resistant pathogens a new drug class, the echinocandins, has recently been introduced. Cross-resistance between these new, intravenous agents and other antifungals has not been observed due their unique mechanism of action within the fungal cell wall. However C. parapsilosis and C. guillermondii are often resistant to this class, and other Candida spp. have developed resistance when exposed to echinocandin therapy19, 20. Unfortunately, the echinocandin class of antifungal agents is available only in an intravenous preparation so that their use in non-complicated oropharyngeal candidiasis is very limited. Thus, resistance of yeast to antifungals remains a significant clinical problem.

PATHOGENESIS

Candida spp. are part of the normal skin, genitourinary, and gastrointestinal microflora. In fact, C. albicans has been isolated in up to 65% of healthy individuals without signs of clinical disease. However under immunocompromising conditions the incidence of carriage may increase and rapid conversion to symptomatic infection may occur5. Protection against the conversion of yeast from colonizer to opportunistic/invasive pathogen is provided by both systemic and local immunity 21. Th-1 type immunity provided by CD4+ T-lymphocytes is a critical component of protection and secondary defense is provided by CD8+ T-lymphocytes and oral epithelial cells through a variety of mechanisms.

The absolute CD4+ T-lymphocyte count has traditionally been cited as the greatest risk factor for the development of OPC and current guidelines suggest increased risk once CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts fall below 200 cells/μL (<15%). Yet OPC remains more common in HIV-infected patients than those with a similar degree of immunosuppression (bone marrow transplant, or patients receiving chemotherapy). This observation suggests that HIV itself may play a role in host susceptibility. Recent studies support this finding and suggest that the HIV viral load may be as important or more important than the CD4+ cell count. The absence of CD4+ T-lymphocytes in a murine model of oral candidiasis did not enhance host development of OPC22, 23 although transgenic mice expressing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 within immune cells were at an increased risk to develop OPC24. Additionally, some authors have found the HIV viral load the most predictive factor in the development of OPC25 and the development of OPC is thought to increase once the HIV-viral loads surpasses 10,000 copies/mL25. This data is further corroborated by the observation that an improvement in CD4 T-lymphoctye cell counts following the initiation of antiretroviral therapy does not fully account for the reduction in the observed incidence of OPC 26.

Candida spp. have a multitude of virulence factors responsible for the ability to cause invasive infection. Their abilities to adhere to both endothelial and epithelial cells, develop hyphae/pseudohyphae, secrete proteinases and other lytic enzymes, and the capacity for phenotypic switching to gain access to the inside of a cell have all been found to play a role in pathogenesis27.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION/PHYSICAL FINDINGS

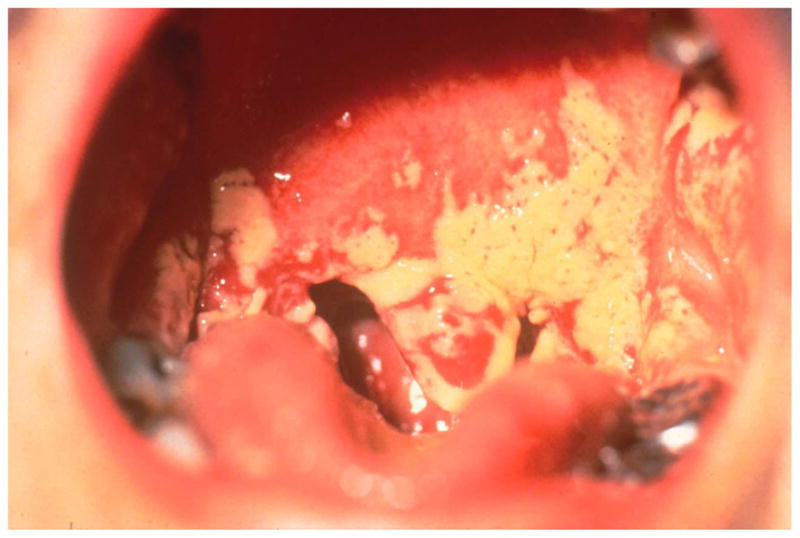

OPC may be the patient’s initial complaint prompting the clinician to consider testing for HIV or it may be incidentally discovered. The pseudomembranous form most commonly occurs when CD4+ cell counts drop below 200 cells/μL (Figure 1). This form appears as painless, creamy white, plaque-like lesions on the tongue, palate, buccal mucosa, or oropharynx and is frequently asymptomatic. Pseudomembranous lesions can typically be “wiped” away from the underlying mucosa28.

FIGURE 1.

Pseudomembranous form of OPC.

Chronic atrophic candidiasis is more common in older adults and is typically located under dentures and consists primarily of erythema without plaque formation. This form may be more frequently recognized as the HIV-infected population continues to age due to improved survival. Angular cheilitis (painful fissuring at the corners of the mouth) has also been attributed to Candida overgrowth and is frequently overlooked by even the astute clinician (Figure 2). Although OPC is frequently asymptomatic, dysguesia or a “cotton” taste are the most frequent complaints. Pain during eating or swallowing are often harbingers of more extensive disease such as Candida esophagitis.

FIGURE 2.

Erythematous candidiasis and angular cheilitis secondary to oropharyngeal candidiasis.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of OPC is generally a clinical one. Oropharyngeal swab cultures may demonstrate Candida species, but since colonization of the oral mucosa by Candida is common, this is not necessarily diagnostic. Confirmation of a diagnosis of oral candidiasis can be accomplished via a 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) slide preparation of a mucosal scraping from a suggestive oral lesion. Others have found periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) staining yields higher sensitivity in the detection and identification of fungal organisms, and in some cases, may reveal the presence of fungi that were not detected in a KOH preparation. Microscopic examination characteristically reveals pseudohyphae and budding yeast forms. However the diagnosis of OPC is often made presumptively and a trial of antifungal therapy initiated. If oral lesions fail to improve despite compliance with antifungal therapy, attempts to ensure that a definitive diagnosis has been made, and the possibility of a resistant organism should be explored. This commonly requires culture and susceptibility testing. However improved culture screening and PCR methods that may expedite accurate diagnosis are currently in development.

A presumptive diagnosis of Candida esophagitis can be made in the OPC patient with dysphagia. Barium swallow is often suggestive, but endoscopy is required for definitive diagnosis. Prior to these expensive and more invasive measures a trial of fluconazole is prudent29. Most patients with esophageal candidiasis respond to antifungal therapy within 3–7 days30. Empirical oral antifungal therapy with fluconazole has been found highly efficacious, safe, and cost-effective for HIV-infected patients with new-onset esophageal symptoms31. Earlier endoscopy without a trial of empiric antifungal therapy may be pursued in those without concurrent OPC or with atypical symptoms. If the patient fails to improve with appropriate systemic antifungal therapy, then endoscopy is indicated to exclude other causes of esophagitis including herpes simplex virus (HSV) or cytomegalovirus (CMV), both common causes of esophagitis in immunocompromised populations.

MANAGEMENT AND TREATMENT

A number of antifungal agents are available for the treatment of OPC (Table 2). However fluconazole remains first-line therapy and is typically administered as 100mg or 200mg per day and continued for 7–14 days after the resolution of symptoms32. Recent data suggests a one-time dose of fluconazole 750mg for the treatment of OPC is as effective and has an equivalent relapse rate to that of standard therapy33. This strategy may provide lower costs and allow for directly observed therapy thus ensuring patient compliance.

Table 2.

Treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC)

| First-line agents 1,2 | |

| Fluconazole (PO or IV) | 100–200 mg daily |

| Clotrimazole troches | 10mg five times daily |

| Nystatin suspension or pastilles | 400,000 units four times daily |

| Second-line agents if above contraindicated | |

| Itraconazole solution (PO) | 200mg daily |

| Voriconazole (PO or IV) | 200mg twice daily |

| Posaconazole (PO) | 400mg daily in divided doses |

| Agents used in refractory OPC | |

| Caspofungin (IV) | 70mg loading dose followed by 50mg daily |

| Micafungin (IV) | 100–150mg daily |

| Anidulafungin (IV) | 100mg loading dose followed by 50mg daily |

| Amphotericin B oral suspension | 500mg every 6 hours |

| Amphotericin B deoxycholate (IV)3 | 0.3mg/kg daily |

Fluconazole is recommended for moderate-to-severe disease, and topical therapy with clotrimazole or nystatin is recommended for mild disease.

Oral fluconazole is preferred in esophageal candidiasis. For patients unable to tolerate an oral agent, IV fluconazole, an echinocandin, or an amphotericin B preparation is appropriate and this condition should be treated for 14–21 days.

Lipid formulations of amphotericin B are viable alternatives with the advantage of less nephrotoxicity than amphotericin B deoxycholate

Topical clotrimazole troches or nystatin suspension are recommended under existing guidelines although the frequency of administration and palatability of these options reduces their attractiveness compared to once daily oral fluconazole. Relapse is also more common when topical therapy is prescribed34. Itraconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole have also been found effective in the treatment of OPC, however few situations exist where they would be preferred over fluconazole as a first-line agent35.

A minority of patients with OPC have refractory disease, and fail treatment with fluconazole. This scenario is most common in those with advanced HIV infection who are heavily fluconazole exposed. Current guidelines suggest itraconazole solution following fluconazole failure, and prior reports have observed a 64–80% success rate with this strategy32, 34, 36. Oral amphotericin solution has shown to be effective in some of these cases but must be compounded by a pharmacy, since it is not available commercially in the US37. A compounding pharmacy can be located by calling 1-800-927-4227, or the use of the International Academy of Compounding Pharmacists website (http://www.iacprx.org). Posaconzole has been found effective in 74% of patients who failed previous antifungal therapy and voriconazole is likely equally effective38, 39. Echinocandins may be useful in this setting due to their unique mechanism of action and thus lack of overlapping resistance with the triazoles40–42. This new class of agents inhibit the synthesis of β-1,3 glucan, a component of the fungal cell wall. This inhibition impairs cell wall integrity and leads to osmotic lysis. Although these agents are only available intravenously - somewhat limiting their use in the outpatient setting.

Infrequently these agents are ineffective and intravenous amphotericin B is required43. Immunomodulatory attempts have been made using granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) however use of the agents should be restricted to specialists within the field and attempted only when other options have been exhausted44, 45.

Esophageal candidiasis warrants systemic therapy and topical agents should not be used. A 14–21 day course of fluconazole or oral itraconazole is usually effective. Intravenous caspofungin, micafungin, and anidulafungin are also approved for use in the treatment of esophageal candidiasis41, 42, however these agents have a greater relapse rate than fluconazole and are more expensive and are not available in an oral formulation. They are thus typically reserved for refractory cases as discussed above.

Although flucytosine has activity against most Candida spp., resistance readily occurs during monotherapy and it should not be used as a single agent in the management of OPC.

Prophylaxis

Neither primary nor secondary prophylaxis are recommended for most patients exhibiting oral or esophageal candidiasis. This recommendation is based on the effectiveness of available therapy, the low attributable mortality, and the potential for resistant Candida spp. to develop over time with continued antifungal pressure. Although if recurrences are frequent or severe, daily fluconazole can be used and continued until immune reconstitution has occurred (CD4 >200 cells/μL)7. Long-term suppressive therapy with fluconazole has been compared to episodic fluconazole use for the development of symptomatic disease. We showed that in patients with frequent relapses effective suppression of recurrent oropharyngeal candidiasis reduced symptomatic relapses17. In that study, mycological resistance was common but not increased in patients receiving either frequent courses of fluconazole for recurrent OPC or with continuous suppressive therapy. In another large trial of the AIDS Clinical Trial Group/Mycoses Study Group (ACTG/MSG), continuous suppressive therapy reduced relapse rates more effectively than intermittent therapy, but was associated with increased mycological resistance although the frequency of refractory disease was the same in each group46.

Antifungal mechanisms of action and drug resistance

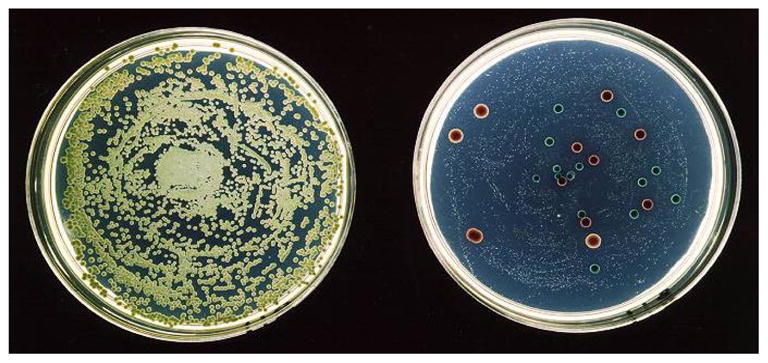

Resistance to antifungal agents is a continuing problem in the most commonly isolated Candida spp. (Table 3). Because susceptibility patterns are usually predictable based on Candida species, culture results that identify the organism to the species level can be very useful to help guide empirical choices of therapy. Although some species harbor intrinsic resistance to varying antifungals (i.e. C. krusei resistance to fluconazole, C. lusitaniase resistance to amphotericin) the development of resistance while receiving appropriate therapy has been well described in several Candida spp. and resistance testing should be considered in refractory or recalcitrant cases. Thus, in patients with refractory infection formal susceptibility testing can be useful. Methods for determining susceptibility to antifungal agents have been established by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI)47. Additional screening methods using disc diffusion have been established for fluconazole and voriconazole48, 49. We previously developed a Chromogenic agar-based screen to rapidly identify heterogenous resistance in oral flora by adding fluconazole to the CHROMagar Candida (BioMeriuux, Marcy l’Etoile, France) (Figure 3)50. Addition of fluconazole to this media suppresses growth of susceptible yeasts (most typically Candida albicans) and allows detection of small numbers of resistant organisms along with their presumptive identification based on phenotypic colony appearance. Although this method is useful in identifying minority populations of resistant Candida spp. it is not currently commercially available. If resistant Candida spp are responsible for clinically apparent disease it is likely unnecessary to use such media as the offending organism will be present in large quantity.

TABLE 3.

Antifungal spectrum of activity against Candida spp.

| Candida spp. | AMB | FLU | ITR | POS | VOR | ANI | MICA | CAS | 5FC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| C. glabrata | + | +/− | +/− | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| C. krusei | + | − | +/− | + | + | + | + | + | +/− |

| C. tropicalis | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| C. parapsilosis | + | + | + | + | + | +/− | +/− | +/− | + |

| C. guillermondii | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + |

| C. lusitaniae | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

AMB, amphotericin; FLU, fluconazole; ITR, itraconazole; POS, posaconazole; VOR, voriconazole; ANI, anidulafungin; MFG, micafungin; CAS, caspofungin; 5FC, flucytosine. (+) implies antifungal activity against isolates, (−) implies no or limited activity against isolate, (+/−) implies variable activity against isolates. Modified from 57.

FIGURE 3.

The agar dilution screening technique allows rapid discernment of isolates with decreased fluconazole susceptibility. Shown are two Chromagar Candida plates which allow rapid species determination based on colony color. More important to this screening method is the inclusion of Fluconazole (8 or 16 mcg/ml). The plate on the left has no fluconazole, and the one on the right contains 8 mcg/ml flu. Without fluconazole, the susceptible C. albicans overwhelms the growth of the other more resistant organisms. With fluconazole (on right), susceptible organisms are suppressed to pinpoint colonies and resistant yeasts are easily seen.

Reproduced with permission 48.

The frequent administration of long-term low-dose fluconazole in the HIV-infected population has resulted in triazole resistant C. albicans isolates51. The mechanisms associated with antifungal resistance in Candida have been extensively investigated over the last several years and several excellent comprehensive reviews have been published51, 52. The azoles target lanosterol 14α-demethylase, the product of the ERG11 gene. Point mutations within this gene are known to confer varying degrees of triazole resistance 53. Drug efflux from cells is another potential mechanism of resistance and overexpression of efflux pumps (CDR1, CDR2, or MDR1) has been correlated with triazole resistance53. Additionally, overexpression of lanosterol 14 -demethylase, the target enzyme, may also occur. More recently mutations in transcription factors as well as other mechanisms have also been described (Table 4) 54–58.

Table 4.

Summary of selected mechanisms responsible for antifungal resistance in Candida spp.

| Gene | Gene product | Mechanism of Resistance | Antifungal class |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERG11 | Lanosterol 14α-demethylase enzyme involved in synthesis of ergosterol. | Point mutations or upregulation of gene result in decreased affinity or overexpression | Triazoles |

| CDR1/CDR2 | Membrane pump belonging To ABC superfamily | Overexpression results in multidrug efflux | Triazoles |

| MDR1 | Membrane pump belonging To ABC superfamily | Overexpression results in multidrug efflux | Triazoles |

| FKS1/FKS2 | Glucan synthase | Point mutations found to alter binding affinity of Echinocandins | Echinocandins |

| TAC1 | Tac1p protein | Transcription factor responsible for upregulation of CDR1/CDR2 if point mutations occur. | Triazoles |

| PDR1 | Pdr1p protein | Transcription factor responsible for upregulation of CDR1 if point mutations occur. | Triazoles |

| MRR1 | Mrr1p protein | Transcription factor responsible for upregulation of MDR1 if point mutations occur. | Triazoles |

Although rare, recent reports have also illustrated the potential for echinocandin resistance to emerge during therapy19, 59. Some of these reports describing reduced echinocandin susceptibility in Candida isolates have identified mutations within genes encoding subunits of the glucan synthase complex, the target of echinocandins. All mutations described to date reside within highly conserved regions of FKS1 or its homolog, FKS2. These genes are known to encode a large integral membrane protein subunit of the glucan synthase complex and thus point mutations confer a reduction in echinocandin in vitro and in vivo efficacy 19, 60–63.

In conclusion oropharyngeal candidiasis remains a significant problem in those with HIV. Fluconazole remains the standard of care in the treatment of this condition. However resistance to the triazoles and other antifungal agents has been described. These recent reports have illustrated the potential for resistant species to emerge despite therapy and have mandated clinicians possess a working knowledge of alternative antifungal agents.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by a National Institute of Health research grant to T.F.P. (5RO1DE018096).

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

G.R.T. has served as a consultant for Basilea. T.F.P. has received research support from Basilea, Merck, Pfizer, and Schering-Plough, and has served as a consultant for Basilea and Pfizer. S.W.R. has received research support from Pfizer, Schering-Plough, and Astellas.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Cameron DW, Heath-Chiozzi M, Danner S, Cohen C, Kravcik S, Maurath C, et al. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of ritonavir in advanced HIV-1 disease. The Advanced HIV Disease Ritonavir Study Group. Lancet. 1998;351(9102):543–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)04161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hood S, Bonington A, Evans J, Denning D. Reduction in oropharyngeal candidiasis following introduction of protease inhibitors. AIDS (London, England) 1998;12(4):447–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Revankar SG, Sanche SE, Dib OP, Caceres M, Patterson TF. Effect of highly active antiretroviral therapy on recurrent oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-infected patients. AIDS (London, England) 1998;12(18):2511–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerdpon D, Pongsiriwet S, Pangsomboon K, Iamaroon A, Kampoo K, Sretrirutchai S, et al. Oral manifestations of HIV infection in relation to clinical and CD4 immunological status in northern and southern Thai patients. Oral diseases. 2004;10(3):138–44. doi: 10.1046/j.1601-0825.2003.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein RS, Harris CA, Small CB, Moll B, Lesser M, Friedland GH. Oral candidiasis in high-risk patients as the initial manifestation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. The New England journal of medicine. 1984;311(6):354–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408093110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powderly WG. Resistant candidiasis. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 1994;10(8):925–9. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adult Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections Guidelines Working Group. Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents [DRAFT] [Accessed June 18, 2009]; [Google Scholar]

- 8.Revankar SG, Kirkpatrick WR, McAtee RK, Dib OP, Fothergill AW, Redding SW, et al. Detection and significance of fluconazole resistance in oropharyngeal candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. The Journal of infectious diseases. 1996;174(4):821–7. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.4.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redding S, Smith J, Farinacci G, Rinaldi M, Fothergill A, Rhine-Chalberg J, et al. Resistance of Candida albicans to fluconazole during treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in a patient with AIDS: documentation by in vitro susceptibility testing and DNA subtype analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18(2):240–2. doi: 10.1093/clinids/18.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fan-Havard P, Capano D, Smith SM, Mangia A, Eng RH. Development of resistance in candida isolates from patients receiving prolonged antifungal therapy. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 1991;35(11):2302–5. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.11.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Revankar SG, Dib OP, Kirkpatrick WR, McAtee RK, Fothergill AW, Rinaldi MG, et al. Clinical evaluation and microbiology of oropharyngeal infection due to fluconazole-resistant Candida in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26(4):960–3. doi: 10.1086/513950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martins MD, Lozano-Chiu M, Rex JH. Declining rates of oropharyngeal candidiasis and carriage of Candida albicans associated with trends toward reduced rates of carriage of fluconazole-resistant C. albicans in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(5):1291–4. doi: 10.1086/515006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erlandsen JEPP, Vallor AC, Kirkpatrick WR, Thompson GR, III, Herrera ML, Wickes BL, Berg DK, Westbrook SD, Redding SW, Patterson TF. Current Prevalence of Candida spp. Colonization, Oropharyngeal Candidiasis (OPC) and Fluconazole (FLU) Resistance in HIV/AIDS Patients Using Combined Microbiological and Molecular Methods of Detection. Programs and Abstracts of the 48th Annual ICAAC/IDSA 46th Annual Meeting; Washington D.C. 2008. Poster M-718. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Westbrook SD, Kirkpatrick WR, Freytes CO, Toro JJ, Bernardo S, Patterson TF, et al. Candida krusei sepsis secondary to oral colonization in a hemopoietic stem cell transplant recipient. Med Mycol. 2007;45(2):187–90. doi: 10.1080/13693780601164306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Redding SW, Marr KA, Kirkpatrick WR, Coco BJ, Patterson TF. Candida glabrata sepsis secondary to oral colonization in bone marrow transplantation. Med Mycol. 2004;42(5):479–81. doi: 10.1080/13693780410001731574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Redding SW, Dahiya MC, Kirkpatrick WR, Coco BJ, Patterson TF, Fothergill AW, et al. Candida glabrata is an emerging cause of oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients receiving radiation for head and neck cancer. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology, oral radiology, and endodontics. 2004;97(1):47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Revankar SG, Kirkpatrick WR, McAtee RK, Dib OP, Fothergill AW, Redding SW, et al. A randomized trial of continuous or intermittent therapy with fluconazole for oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-infected patients: clinical outcomes and development of fluconazole resistance. The American journal of medicine. 1998;105(1):7–11. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ally R, Schurmann D, Kreisel W, Carosi G, Aguirrebengoa K, Dupont B, et al. A randomized, double-blind, double-dummy, multicenter trial of voriconazole and fluconazole in the treatment of esophageal candidiasis in immunocompromised patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(9):1447–54. doi: 10.1086/322653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thompson GR, 3rd, Wiederhold NP, Vallor AC, Villareal NC, Lewis JS, 2nd, Patterson TF. Development of caspofungin resistance following prolonged therapy for invasive candidiasis secondary to Candida glabrata infection. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2008;52(10):3783–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00473-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laverdiere M, Lalonde RG, Baril JG, Sheppard DC, Park S, Perlin DS. Progressive loss of echinocandin activity following prolonged use for treatment of Candida albicans oesophagitis. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2006;57(4):705–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fidel PL., Jr Distinct protective host defenses against oral and vaginal candidiasis. Med Mycol. 2002;40(4):359–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacasse M, Fortier C, Chakir J, Cote L, Deslauriers N. Acquired resistance and persistence of Candida albicans following oral candidiasis in the mouse: a model of the carrier state in humans. Oral microbiology and immunology. 1993;8(5):313–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1993.tb00580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deslauriers N, Cote L, Montplaisir S, de Repentigny L. Oral carriage of Candida albicans in murine AIDS. Infection and immunity. 1997;65(2):661–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.661-667.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Repentigny L, Aumont F, Ripeau JS, Fiorillo M, Kay DG, Hanna Z, et al. Mucosal candidiasis in transgenic mice expressing human immunodeficiency virus type 1. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2002;185(8):1103–14. doi: 10.1086/340036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mercante DE, Leigh JE, Lilly EA, McNulty K, Fidel PL., Jr Assessment of the association between HIV viral load and CD4 cell count on the occurrence of oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-infected patients. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2006;42(5):578–83. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000225011.76439.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cauda R, Tacconelli E, Tumbarello M, Morace G, De Bernardis F, Torosantucci A, et al. Role of protease inhibitors in preventing recurrent oral candidosis in patients with HIV infection: a prospective case-control study. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 1999;21(1):20–5. doi: 10.1097/00126334-199905010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fidel PL., Jr Candida-host interactions in HIV disease: relationships in oropharyngeal candidiasis. Advances in dental research. 2006;19(1):80–4. doi: 10.1177/154407370601900116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powderly WG, Mayer KH, Perfect JR. Diagnosis and treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients infected with HIV: a critical reassessment. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 1999;15(16):1405–12. doi: 10.1089/088922299309900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabeneck L, Laine L. Esophageal candidiasis in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. A decision analysis to assess cost-effectiveness of alternative management strategies. Archives of internal medicine. 1994;154(23):2705–10. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1994.00420230096011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilcox CM. Short report: time course of clinical response with fluconazole for Candida oesophagitis in patients with AIDS. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 1994;8(3):347–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1994.tb00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilcox CM, Alexander LN, Clark WS, Thompson SE., 3rd Fluconazole compared with endoscopy for human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with esophageal symptoms. Gastroenterology. 1996;110(6):1803–9. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8964406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, Benjamin DK, Jr, Calandra TF, Edwards JE, Jr, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(5):503–35. doi: 10.1086/596757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamza OJ, Matee MI, Bruggemann RJ, Moshi MJ, Simon EN, Mugusi F, et al. Single-dose fluconazole versus standard 2-week therapy for oropharyngeal candidiasis in HIV-infected patients: a randomized, double-blind, double-dummy trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(10):1270–6. doi: 10.1086/592578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Phillips P, Zemcov J, Mahmood W, Montaner JS, Craib K, Clarke AM. Itraconazole cyclodextrin solution for fluconazole-refractory oropharyngeal candidiasis in AIDS: correlation of clinical response with in vitro susceptibility. AIDS (London, England) 1996;10(12):1369–76. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199610000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vazquez JA, Skiest DJ, Nieto L, Northland R, Sanne I, Gogate J, et al. A multicenter randomized trial evaluating posaconazole versus fluconazole for the treatment of oropharyngeal candidiasis in subjects with HIV/AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(8):1179–86. doi: 10.1086/501457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saag MS, Fessel WJ, Kaufman CA, Merrill KW, Ward DJ, Moskovitz BL, et al. Treatment of fluconazole-refractory oropharyngeal candidiasis with itraconazole oral solution in HIV-positive patients. AIDS research and human retroviruses. 1999;15(16):1413–7. doi: 10.1089/088922299309919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fichtenbaum CJ, Zackin R, Rajicic N, Powderly WG, Wheat LJ, Zingman BS. Amphotericin B oral suspension for fluconazole-refractory oral candidiasis in persons with HIV infection. Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study Team 295. AIDS (London, England) 2000;14(7):845–52. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200005050-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skiest DJ, Vazquez JA, Anstead GM, Graybill JR, Reynes J, Ward D, et al. Posaconazole for the treatment of azole-refractory oropharyngeal and esophageal candidiasis in subjects with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(4):607–14. doi: 10.1086/511039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hegener P, Troke PF, Fatkenheuer G, Diehl V, Ruhnke M. Treatment of fluconazole-resistant candidiasis with voriconazole in patients with AIDS. AIDS (London, England) 1998;12(16):2227–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Villanueva A, Arathoon EG, Gotuzzo E, Berman RS, DiNubile MJ, Sable CA. A randomized double-blind study of caspofungin versus amphotericin for the treatment of candidal esophagitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(9):1529–35. doi: 10.1086/323401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Wet N, Llanos-Cuentas A, Suleiman J, Baraldi E, Krantz EF, Della Negra M, et al. A randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, dose-response study of micafungin compared with fluconazole for the treatment of esophageal candidiasis in HIV-positive patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(6):842–9. doi: 10.1086/423377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krause DS, Simjee AE, van Rensburg C, Viljoen J, Walsh TJ, Goldstein BP, et al. A randomized, double-blind trial of anidulafungin versus fluconazole for the treatment of esophageal candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(6):770–5. doi: 10.1086/423378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dewsnup DH, Stevens DA. Efficacy of oral amphotericin B in AIDS patients with thrush clinically resistant to fluconazole. J Med Vet Mycol. 1994;32(5):389–93. doi: 10.1080/02681219480000511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vazquez JA, Hidalgo JA, De Bono S. Use of sargramostim (rh-GM-CSF) as adjunctive treatment of fluconazole-refractory oropharyngeal candidiasis in patients with AIDS: a pilot study. HIV clinical trials. 2000;1(3):23–9. doi: 10.1310/LF5T-WYY7-0U3E-G8BQ. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bodasing N, Seaton RA, Shankland GS, Pithie A. Gamma-interferon treatment for resistant oropharyngeal candidiasis in an HIV-positive patient. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2002;50(5):765–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goldman M, Cloud GA, Wade KD, Reboli AC, Fichtenbaum CJ, Hafner R, et al. A randomized study of the use of fluconazole in continuous versus episodic therapy in patients with advanced HIV infection and a history of oropharyngeal candidiasis: AIDS Clinical Trials Group Study 323/Mycoses Study Group Study 40. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(10):1473–80. doi: 10.1086/497373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts. Approved standard neM-ANCfCL 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barry AL, Brown SD. Fluconazole disk diffusion procedure for determining susceptibility of Candida species. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1996;34(9):2154–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2154-2157.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pfaller MA, Boyken L, Messer SA, Tendolkar S, Hollis RJ, Diekema DJ. Comparison of results of voriconazole disk diffusion testing for Candida species with results from a central reference laboratory in the ARTEMIS global antifungal surveillance program. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2005;43(10):5208–13. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.10.5208-5213.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Patterson TF, Revankar SG, Kirkpatrick WR, Dib O, Fothergill AW, Redding SW, et al. Simple method for detecting fluconazole-resistant yeasts with chromogenic agar. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1996;34(7):1794–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1794-1797.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.White TC, Marr KA, Bowden RA. Clinical, cellular, and molecular factors that contribute to antifungal drug resistance. Clinical microbiology reviews. 1998;11(2):382–402. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.2.382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perlin DS. Resistance to echinocandin-class antifungal drugs. Drug Resist Updat. 2007;10(3):121–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White TC, Holleman S, Dy F, Mirels LF, Stevens DA. Resistance mechanisms in clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2002;46(6):1704–13. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.6.1704-1713.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Coste A, Turner V, Ischer F, Morschhauser J, Forche A, Selmecki A, et al. A mutation in Tac1p, a transcription factor regulating CDR1 and CDR2, is coupled with loss of heterozygosity at chromosome 5 to mediate antifungal resistance in Candida albicans. Genetics. 2006;172(4):2139–56. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.054767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Coste A, Selmecki A, Forche A, Diogo D, Bougnoux ME, d’Enfert C, et al. Genotypic evolution of azole resistance mechanisms in sequential Candida albicans isolates. Eukaryotic cell. 2007;6(10):1889–904. doi: 10.1128/EC.00151-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morschhauser J, Barker KS, Liu TT, Bla BWJ, Homayouni R, Rogers PD. The transcription factor Mrr1p controls expression of the MDR1 efflux pump and mediates multidrug resistance in Candida albicans. PLoS pathogens. 2007;3(11):e164. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schubert S, Rogers PD, Morschhauser J. Gain-of-function mutations in the transcription factor MRR1 are responsible for overexpression of the MDR1 efflux pump in fluconazole-resistant Candida dubliniensis strains. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2008;52(12):4274–80. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00740-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferrari S, Ischer F, Calabrese D, Posteraro B, Sanguinetti M, Fadda G, et al. Gain of function mutations in CgPDR1 of Candida glabrata not only mediate antifungal resistance but also enhance virulence. PLoS pathogens. 2009;5(1):e1000268. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hernandez S, Lopez-Ribot JL, Najvar LK, McCarthy DI, Bocanegra R, Graybill JR. Caspofungin resistance in Candida albicans: correlating clinical outcome with laboratory susceptibility testing of three isogenic isolates serially obtained from a patient with progressive Candida esophagitis. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2004;48(4):1382–3. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1382-1383.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Douglas CM, D’Ippolito JA, Shei GJ, Meinz M, Onishi J, Marrinan JA, et al. Identification of the FKS1 gene of Candida albicans as the essential target of 1,3-beta-D-glucan synthase inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41(11):2471–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Douglas CM, Marrinan JA, Li W, Kurtz MB. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutant with echinocandin-resistant 1,3-beta-D-glucan synthase. J Bacteriol. 1994;176(18):5686–96. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.18.5686-5696.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kurtz MB, Abruzzo G, Flattery A, Bartizal K, Marrinan JA, Li W, et al. Characterization of echinocandin-resistant mutants of Candida albicans: genetic, biochemical, and virulence studies. Infect Immun. 1996;64(8):3244–51. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3244-3251.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park S, Kelly R, Kahn JN, Robles J, Hsu MJ, Register E, et al. Specific substitutions in the echinocandin target Fks1p account for reduced susceptibility of rare laboratory and clinical Candida sp. isolates Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(8):3264–73. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3264-3273.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]