Summary

Background

Both opioid antagonist administration and cigarette smoking acutely increase hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activity as measured by adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol levels. However, male and female smokers may differ in their response to the opioid antagonist naltrexone, which may be partially mediated by sex differences in HPA axis function. Smokers, as a group, have frequently been shown to have HPA axis dysfunction, which may have relevance to the course and maintenance of nicotine dependence. The purpose of this study was to examine possible sex differences in HPA axis function by comparing stress-hormone response to naltrexone within healthy male and female smokers. Additionally, exploratory analyses compared the combined effects of naltrexone and cigarette smoking on hormonal responsivity between the sexes.

Method

Thirty-eight healthy smokers (22 men) were tested in two separate morning sessions after 12 hours of smoking abstinence. For women, self reports of menstrual cycle information were obtained prior to each session (date of last menstruation, cycle length, reproductive phase, etc.). Each participant received 50 mg naltrexone or placebo capsule (in random order) and plasma levels of ACTH and cortisol were assessed at regular intervals for several hours. A subgroup of twelve participants underwent a similar, additional session in which they smoked a single cigarette three hours after naltrexone administration.

Results

Naltrexone significantly increased ACTH and cortisol levels in women, but not men (Drug*Sex*Time, p<0.05). A post hoc analysis suggested that women at an estimated ‘high estrogen’ phase had a greater cortisol response (Dose*Estrogen Level, p<0.05) than those at an estimated ‘low estrogen’ phase. Exploratory analyses showed that smoking a single cigarette potentiated naltrexone-induced increases in ACTH (p<0.05) and cortisol (p<0.01) in all participants.

Conclusion

The findings support the hypothesis that women are more sensitive to opioid antagonism at the level of the HPA axis. Although further studies are needed to examine mechanisms underlying these responses, both results may have clinical implications for the use of naltrexone as a treatment for nicotine dependence.

Keywords: hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, ACTH, cortisol, naltrexone, cigarette smoking, sex differences

1. Introduction

Nicotine dependence is a chronic relapsing disorder that has been associated with hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction. This HPA axis dysfunction may play a role in maintenance of addiction and susceptibility to relapse (al’Absi et al., 2004a; al’Absi et al., 2005; Shaw and al’Absi 2008). Interestingly, one drug being evaluated for smoking cessation treatment is naltrexone (for review, see King et al., 2009), a primarily mu-opioid receptor antagonist that acutely disinhibits the HPA axis. Although currently the outcomes of smoking cessation studies with naltrexone are mixed (Wong et al., 1999; King et al., 2006; O’Malley et al., 2006), some data suggest that women smokers (vs. men) may be more sensitive to naltrexone and show better clinical outcomes compared with placebo (Covey et al., 1999; King et al., 2006). Men and women differ in HPA axis responsivity (Uhart et al., 2006; Kudielka et al., 2009) and, thus, also may differ in hormonal response to naltrexone. The purpose of this placebo-controlled, pre-clinical human laboratory study in smokers was to investigate whether the sexes differ in HPA hormone reactivity to naltrexone.

Nicotine dose-dependently activates the HPA axis (Winternitz and Quillen 1977; Wilkins et al., 1982; Kirschbaum et al., 1992; Mendelson et al., 2005; Mendelson et al., 2008). In vitro and in vivo studies show that nicotine activates the HPA axis via nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAchRs) of norepinephrine (NE) neurons of the nucleus of the solitary tract, which project to and activate the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus (Hill and Wynder 1974; Matta et al., 1998; Fu et al., 2001). Hypothalamic activation and subsequent corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) secretion induces the release of adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) from the anterior lobe of the pituitary, which in turn stimulates cortisol secretion from the adrenal gland. Accordingly, in humans, cigarette smoking acutely increases norepinephrine (Hill and Wynder 1974; Cryer et al., 1976; Narkiewicz et al., 1998), cortisol (Wilkins et al., 1982; Pomerleau and Pomerleau 1990; Meliska and Gilbert 1991; Baron et al., 1995), ACTH (Mendelson et al., 2005; Mendelson et al., 2008), and β-endorphin/β-lipotrophin levels (Pomerleau et al., 1983). Chronic nicotine exposure and/or nicotine withdrawal alters HPA axis function and stress responsivity (for review, see Rohleder and Kirschbaum 2006). Smokers show attenuated cortisol response and prolonged subjective distress to biobehavioral stressors compared to nonsmokers (Perkins et al., 1992; Kirschbaum et al., 1993; Kirschbaum et al., 1994; Tsuda et al., 1996; al’Absi et al., 2003; al’Absi et al., 2008; Childs and de Wit 2009). Furthermore, during early smoking abstinence, which may also be considered a stressor, low diurnal cortisol and/or dampened β-Endorphin, ACTH, and cortisol responses to a psychosocial stressor are predictive of exaggerated withdrawal symptoms, negative affect, and early relapse (al’Absi et al., 2004a; al’Absi et al., 2005; Shaw and al’Absi 2008).

Endogenous opioids maintain an inhibitory tone over the HPA axis (Kreek et al., 1972; Kreek 1973; Cushman and Kreek 1974; Kreek 1978; Johnson et al., 1992). Specifically, β-endorphins act directly on μ-opioid receptors in the hypothalamus to inhibit CRH release from the PVN (Johnson et al., 1992) and indirectly on neurons of the locus coeruleus to inhibit NE release (Valentino and Van Bockstaele 2001). Consistent with this mechanism, opioid antagonists, such as naloxone and naltrexone, remove this tonic HPA inhibition and acutely increase ACTH and cortisol levels (Volavka et al., 1979; Morley et al., 1980; Naber et al., 1981; Cohen et al., 1983; Kreek et al., 1984; Conaglen et al., 1985; Delitala et al., 1994; Martin del Campo et al., 1994; Schluger et al., 1998; Farren et al., 1999; King et al., 2002; al’Absi et al., 2004b; al’Absi et al., 2008). There is both preclinical and clinical evidence that the endogenous opioid system may also play an important role in response to nicotine and development of dependence (for review, see King et al., 2009). In preclinical studies, nAchR antagonists block the analgesic effects of opiates (Schmidt et al., 2001) and, conversely, opioid receptor antagonists block the antinociceptive effects of nicotine (Aceto et al., 1993). Morphine produces a leftward shift of the nicotine dose-response curve (Huston-Lyons et al., 1993) and there is cross-tolerance between morphine and nicotine (Zarrindast et al., 2003). In both pre-clinical and clinical studies, opioids and nicotine produce similar withdrawal patterns (Hynes et al., 1976; Malin et al., 1993; Malin et al., 1996a; Malin et al., 1996b; Krishnan-Sarin et al., 1999; Berrendero et al., 2002; Berrendero et al., 2005). Finally, the release of cortisol and ACTH after opioid antagonist administration is attenuated in cigarette smokers compared to nonsmokers (Krishnan-Sarin et al., 1999; al’Absi et al., 2008). Despite preclinical and clinical evidence for the interaction between nicotine and opioids, currently it is unclear whether an opioid antagonist, such as naltrexone, along with standard smoking cessation treatment, may improve smoking quit rates (David et al., 2006).

There is evidence that HPA axis function may differ in men and women. For example, men tend to exhibit greater HPA axis response to psychological stressors (Kirschbaum et al., 1992; Kirschbaum et al., 1995b; Kirschbaum et al., 1995a; Kudielka et al., 1998; Kirschbaum et al., 1999; Uhart et al., 2006), while women tend to exhibit greater HPA axis response to acute pharmacological challenges, such as naloxone and CRH (Gallucci et al., 1993; Heuser et al., 1994; Born et al., 1995; Kunzel et al., 2003; Uhart et al., 2006). Sex differences in opioid-induced HPA response may be due to variations in central endogenous opioid function (Zubieta et al., 2002). For example, compared with men, women exhibit higher μ-binding affinity throughout the brain (Zubieta et al., 1999). Further, women report greater antinociceptive effects and subjective response to drugs that act on μ- and/or κ-receptors, including naltrexone (Gear et al., 1996a; Gear et al., 1996b, 1999; Sarton et al., 2000; Zacny 2001; Gear et al., 2003; al’Absi et al., 2004b); for review, see Fillingim and Gear 2004). Moreover, preliminary studies suggest that female smokers may show differential sensitivity to naltrexone compared with male smokers, suggested by greater levels of naltrexone-induced withdrawal symptoms and side effects as well as better clinical outcomes in smoking cessation trials (Covey et al., 1999; Epstein and King 2004; King et al., 2006). Taken together, these findings underscore the need for more research within smokers on mechanisms and potential sex differences in opioid-HPA responsivity.

The evidence described above suggests that there may be sex differences in response to naltrexone in male and female smokers. While acute administration of either nicotine or naltrexone can independently increase HPA axis activity, there is little information on their potential interactive effects. This issue has important translational ramifications to clinical outcomes, as approximately half of all smokers making a quit attempt smoke during the first week after the quit date (Hughes et al., 2004). In terms of underlying mechanisms, it would be of interest to know whether an opioid antagonist such as naltrexone, which disinhibits the HPA axis, combined with exposure to a cigarette, which also activates HPA axis, produces either synergistic effects on HPA axis hormone levels, or if naltrexone’s disinhibition of the HPA axis reaches threshold without further smoking-induced changes. Thus, the aims of the present study were 1) to compare the men and women smokers’ HPA axis responsivity (plasma ACTH and cortisol) to an acute dose of naltrexone versus placebo, and 2) to explore naltrexone’s effects on HPA axis responsivity after acute cigarette smoking. Based upon previous findings (Klein et al., 2000; Epstein and King 2004; King et al., 2006; Uhart et al., 2006), we hypothesized that female smokers would exhibit greater HPA axis responsivity to naltrexone than male smokers. Additionally, based upon evidence that both nicotine and opioid antagonists activate the HPA axis, we predicted that a single cigarette would potentiate naltrexone-related increases in ACTH and cortisol, and such effects would be more pronounced in women.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Participants were 38 adult cigarette smokers (22 men) aged 21–62, recruited through flyers and local Chicago area newspaper advertisements. Participants needed to smoke between 10 and 40 cigarettes daily for two or more years. This smoking cutoff range was implemented in order to maintain relative homogeneity within the sample by including regular smokers, but excluding more extreme users. After an initial phone screen, participants were invited for a screening session in the laboratory. The laboratory screening consisted of a general physical examination by a resident physician, a diagnostic interview, and completion of several screening questionnaires, which included the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., 1961), Symptom Checklist-90 (Derogatis 1983), State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger et al., 1987), Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (Heatherton et al., 1991), Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (Selzer et al., 1975), a drug and health history questionnaire, and the Mood Episodes and Alcohol Use Disorders modules from the Structured Diagnostic Interview for the DSM IV (First et al., 1995). The standard cut-off thresholds of those questionnaires and interviews were used to eliminate those persons with significant current or past alcohol, drug, or psychiatric symptomatology. Individuals were excluded from participation if they had current or past major medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, thyroid disorders, hypertension, neurological disorders, etc.), psychiatric disorders (i.e., any Axis I or major Axis II disorder), or use of medications that may affect HPA axis or opioidergic functioning. Additionally, subjects with abnormal blood chemical and hepatic indices or a positive urine toxicology obtained during the screening (cocaine, opiates, benzodiazepines, amphetamine, barbiturates, and PCP) were excluded from participation.

Women on hormonal birth control were also excluded because oral contraceptives increase diurnal serum cortisol levels and may dampen the increase in cortisol after stress (Kirschbaum et al., 1999; Wiegratz et al., 2003a, b). Furthermore, oral contraceptives have been shown to produce enthinylestradiol-induced increases in corticosteroid binding globulin, which results in an increase total serum cortisol levels (Dhillo et al., 2002; Wiegratz et al., 2003a, b). Women were included if they were currently cycling (i.e., any phase of menstrual cycle), post-menopausal, or post-hysterectomy.

2.2 Procedure

During the screening session, the participant signed an informed consent form prior to participation. The study was approved by The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Naltrexone vs. Placebo Sessions

Each subject participated in two experimental sessions spaced 8.7 ± 4.7 days apart (range 3–21 days with >70% completing within ten days). In this double-blind within-subjects study, participants received either naltrexone or placebo in random order. The 50 mg dose of naltrexone was chosen because it is the FDA-approved dosage for opioid and alcohol dependencies and for consistency, as it is the dose most often used in laboratory (Sutherland et al., 1995; Hutchison et al., 1999; King and Meyer 2000; Epstein and King 2004) and clinical treatment studies with naltrexone for smoking (Covey et al., 1999; Wong et al., 1999; King et al., 2006; O’Malley et al., 2006).

The evening prior to the experimental session (between 1700 and 1830h), the participant arrived for an overnight stay in a private room at the University of Chicago Hospital Clinical Research Center (CRC). The participant was instructed to smoke their usual amount of cigarettes during the day prior to arrival to the CRC and to refrain from alcohol and other drugs for at least 48 hours before arrival. Upon admission to the CRC, the participant submitted breath and urine samples to test for the presence of alcohol or drugs and female participants were tested for pregnancy. All results were negative. The participant submitted to baseline measures including vital signs and questionnaires, and consumed an evening meal provided by the dietetics staff (40% daily calories, based on body weight). Using a calendar method, female participants provided information regarding menstrual cycle, such as days since last menstruation and average length of cycle. During the evening, the participant was allowed to relax and read or watch television. Smoking was not allowed after 2000h (the nurse took the participant’s cigarettes to assure compliance with overnight abstinence), and lights were turned off by midnight.

The following morning, the participant was awoken by 0700h and consumed a light breakfast (20% daily calories). Thirty minutes later, the research nurse inserted an intravenous (i.v.) catheter into a forearm or hand vein. After a 30 minute adaptation period, the participant ingested the capsule (Time 0). The nurse took vital signs at regular intervals throughout testing. Blood samples were obtained at 0, 90, 120, and 180 min for ACTH and at 0, 90, 120, 150, 180, and 210 min for cortisol. The timing of blood collection was chosen based on the bioavailability of orally administered naltrexone and on when hormonal response to naltrexone first becomes reliably evident (King et al., 2002). During intervals when measures were not obtained, the participant was able to relax, watch selected movies or television, or read magazines. At the end of each session, the i.v. catheter was removed and the participant was discharged. At the end of the second session, the participant was debriefed and compensated US$175.

Smoking vs. Non-smoking sessions

As an exploratory study, 12 subjects (men n=7) from the original experiment attended an additional double-blinded laboratory session at the GCRC. This session was randomized in order, i.e. subjects were equally divided in terms of those having this smoking session as their first, second or last session. In this session, subjects received 50 mg naltrexone using identical timing, procedure, and blood-sampling intervals as described in the main study. However, at 180 minutes, the technician instructed the participant to smoke a single cigarette of his/her preferred brand at the usual rate, and additional blood samples were obtained five minutes (for ACTH) and 30 minutes (for cortisol) after smoking the cigarette. In the final portion of the testing sessions, the participant was involved in a choice smoking paradigm, reported elsewhere (Epstein and King 2004).

Neuroendocrine Assays

The samples were stored on ice and spun within fifteen minutes of collection in a refrigerated centrifuge. The samples were then immediately separated into aliquots and stored at −70° C. Hormonal assays were conducted at the Core Laboratory of the GCRC and the Department of Medicine, Endocrinology Laboratories. Cortisol was assayed by radioimmunoassay in duplicate using the Immulite® 1000 immunoassay analyzer (lower sensitivity = .003). For cortisol, intra-assay precision at two different levels was 4.2%–5.7%; inter-assay precision was 7.0%–9.3%. ACTH was analyzed by the automated Nichols Advantage using a chemiluminescent assay technique (Nichols Institute, San Juan Capistrano, CA). For ACTH, intra-assay coefficients of variation were 6.4% for a mean of 12.7; inter-assay coefficients of variation were 7.2% for a mean of 13.7 and 4.2% for a mean of 86. Dependent measures were the average of the duplicated radioimmunoassay derived values at each time point, as well as by area under the curve.

2.3 Statistical Analyses

Differences in demographic characteristics between male and female participants were analyzed using Student’s t-tests. Repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted on ACTH and cortisol with drug (naltrexone, placebo) and time as within-subjects factors and sex as a between-subjects factor. For analyses indicating sex differences, several variables were included as covariates, including age, smoking duration, weight and body mass index (BMI). Age and smoking duration were included to control for potential differences in our sample, while weight and BMI were included to control for differences in body size between men and women, as there is evidence that naltrexone has lipophilic properties (Brown and Goldberg 1985; Ukai and Holtzman 1987). Post-hoc Tukey’s tests were used, where appropriate. For the post-hoc analysis on estimated estrogen level, repeated measures ANOVAs were performed on ACTH and cortisol with drug (naltrexone, placebo) as a within-subjects factor, estimated estrogen level (high, low) as a between-subjects factor, and age, smoking duration, weight, and BMI included as covariates. Finally, within the subgroup of subjects who had the additional smoking session after receiving naltrexone, exploratory ANOVAs were used to compare ACTH and cortisol levels with time and session as within-subjects factors and sex as the between-subjects factor.

3. Results

Naltrexone vs. Placebo Sessions

Demographic and smoking characteristics for male and female participants are shown in Table 1. The racial composition for the sample was 53% White, 29% Black, 5% Asian and 13% Other. Overall, participants smoked an average of 20.8 cigarettes daily (range 13–38) for 19.2 years (range 2– 46 years) with an average FTND score of 5.4 (range 2–9). Although male participants were younger than female participants [t(36)=−2.3 p<0.05], both sexes exhibited similar smoking characteristics (FTND, cigarettes smoked per day, years smoked, and baseline CO, cotinine, and nicotine levels) and similar basal levels of plasma cortisol and ACTH.

Table 1.

Participant demographics and smoking characteristics

| Men (N=22) | Women (N=16) | |

|---|---|---|

| General Characteristics | ||

| Age (years) | 34.1 (2.2) | 41.9 (2.8) * |

| Education (years) | 14.9 (0.5) | 13.7 (0.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.7 (0.7) | 26.0 (1.3) |

| Weight (lbs.) | 170.6 (5.8) | 158.6 (8.5) |

| Race (%White, Black, Asian, Other) | 55/18/9/18 | 50/44/0/6 |

| Smoking Characteristics | ||

| FTND | 5.0 (0.5) | 5.9 (0.3) |

| Cigarettes per day | 21.1 (1.1) | 20.4 (1.2) |

| Smoking duration (years) | 16.1 (2.2) | 23.4 (3.3) |

| Session Baseline Average Levels | ||

| CO readings (ppm) | 8.5 (1.0) | 8.1 (0.6) |

| Cotinine levels (ng/ml) | 202.3 (20.7) | 203.4 (27.1) |

| Nicotine levels (ng/ml) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.63 (0.1) |

| ACTH (pg/ml) | 27.3 (1.9) | 21.0 (3.3) |

| Cortisol (ug/ml) | 19.9 (0.8) | 18.1 (1.3) |

Data indicate mean (SEM). BMI = Body Mass Index. FTND = Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence. Session baseline measures were taken after 12 hours of smoking abstinence. Asterisks indicate significant differences between the sexes (Students t-test, p<0.05).

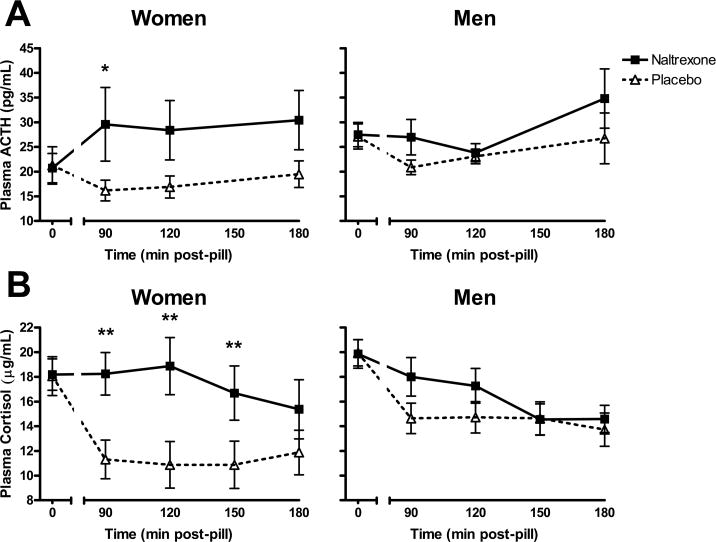

Figure 1a illustrates changes in plasma ACTH across time after naltrexone and placebo for male and female participants. Naltrexone significantly increased ACTH levels in women, but not in men [Drug*Sex*Time: F(3,99)=3.5 p<0.05; Tukey’s: within women, naltrexone > placebo at 90m, p<0.05]. Analysis of area under the curve confirmed women’s greater ACTH response [Drug*Sex: F(1,35)=3.9, p<0.001; Tukey’s: within women, naltrexone > placebo p<.01].

Figure 1.

Naltrexone significantly elevated plasma levels of (a) ACTH and (b) cortisol within women compared with men (ACTH and Cortisol: Drug*Sex*Time p<0.05; Tukey’s Post Hoc: *p<0.05, **p<0.01 ). Hormone levels are reported as mean ± SEM.

Changes in plasma cortisol for male and female participants after naltrexone and placebo are presented in Figure 1b. Cortisol results were similar to ACTH: naltrexone significantly increased cortisol levels in women, but not in men [Drug*Sex*Time: F(4,132)=3.1, p<0.05; Tukey’s: within women, naltrexone> placebo at 90m, 120m, & 150m, p<0.01]. An area under the curve analysis for cortisol supported these findings, with women exhibiting heightened levels after naltrexone [Drug*Sex: F(1,35)=6.0, p<0.001; Tukey’s: within women, naltrexone > placebo at 90m, p<0.001].

Post Hoc Examination of Menstrual Cycle Phase Effects

In order to determine the effects of menstrual cycle phase and, subsequently, of estrogen level on response to naltrexone (see Discussion for details), women were divided into two groups: a ‘low estrogen’ group (n=11) consisting of women in the early and late luteal or early follicular phase of the menstrual cycle or who were post-hysterectomy or post-menopausal and a ‘high estrogen’ group (n=5) consisting of women in the mid to late follicular phase. As measured by area under the curve, women in the low estrogen group had a greater ACTH (Drug*Estrogen Level: F(1,11)=4.1, p=0.068) and cortisol (Drug*Estrogen Level: F(1,11)=9.5, p<0.05) response to naltrexone than women in the high estrogen group.

Smoking vs. Non-smoking sessions

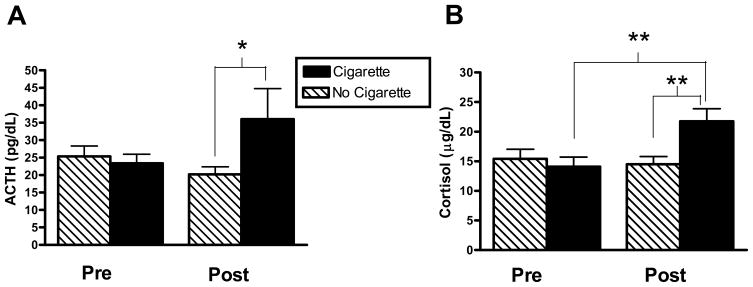

Finally, exploratory analyses were conducted within the naltrexone pretreatment conditions to evaluate the effects of smoking a single cigarette on ACTH and cortisol responses in the subgroup of subjects (n=12) who participated in the additional smoking session. As shown in Figure 2, after naltrexone pretreatment, smoking a cigarette significantly increased ACTH [Session*Time: F(1,11)=6.23, p<0.05, Tukey’s: post-levels, cigarette vs. no cigarette, p<.05, Figure 2a] and cortisol levels [Session*Time: F(1, 11)=14.15, p<0.01, Tukey’s: cigarette, pre- vs. post-levels, p<0.01; post-levels, cigarette vs. no cigarette, p<0.01, Figure 2b]. However, the sexes did not differ after naltrexone pretreatment in ACTH or cortisol response to the cigarette (Cigarette*Sex, ACTH: p=0.35; Cortisol: p=0.46).

Figure 2.

Effects of smoking a single cigarette on naltrexone-potentiated plasma ACTH (2a) and cortisol (2b) levels. “Pre” denotes the last time point prior to smoking for ACTH and cortisol, respectively. “Post” denotes five minutes after smoking the cigarettes for ACTH, and 30 minutes for cortisol. (ACTH: Session*Time p<0.05; Cortisol: Session*Time p<0.01; Tukey’s Post Hoc: *p<0.05, **p<0.01). Hormone levels are reported as mean ± SEM.

4. Discussion

The present study examined the effects of the opioid antagonist naltrexone and cigarette smoking on the HPA axis in male and female smokers. The main study results indicated sex differences in HPA axis response to naltrexone: women exhibited heightened plasma ACTH and cortisol in response to naltrexone as compared to placebo, whereas stress hormone levels among men did not differ across conditions. This finding is consistent with results of studies in nonsmokers with naltrexone (Klein et al., 2000) and naloxone (Uhart et al., 2006), but in contrast to others that did not observe sex differences in ACTH and cortisol responses to acute naltrexone challenge in smokers (al’Absi et al., 2004b; al’Absi et al., 2008). While these discrepancies are difficult to discern, they may relate to the inclusion of women on oral contraceptives in some studies (al’Absi et al., 2004b), to failure to control for fluctuations of estrogen levels within the follicular phase (al’Absi et al., 2008) or across phases of the menstrual cycle (current study), or to individual differences in genotype, all of which may differentially affect stress hormone responsivity in men and women to pharmacological manipulation. Additionally, the age and smoking duration of the current study sample (i.e., middle age with ~20 years smoking duration) are higher than those reported in the studies by al’Absi and colleagues (i.e., young adults with less than 10 years smoking duration). Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that the observed sex differences in response to naltrexone may be due to biological changes in the HPA axis in response to the aging process or to prolonged nicotine exposure. There is evidence that HPA axis responsivity to a psychological stressor differs between elderly and young adults, some of whom were smokers, which suggests that HPA axis function may differ across the lifespan (Seeman et al., 2001; Kudielka et al., 2004). However, it is unclear whether a similar disparity in HPA responsivity exists between young and middle-aged adults and if this may affect response to naltrexone. In addition, while the HPA axis is dysregulated in chronic smokers compared to non-smokers, it is unknown whether different durations of smoking have an effect on HPA axis responsivity.

Several mechanisms may be posited to explain the observed sex differences in HPA axis response to opioid antagonism in the present study. First, women may have greater μ- and κ-opioid receptor sensitivity as compared to men (Gear et al., 1996a; Gear et al., 1996b, 1999; Sarton et al., 2000; Zacny 2001; Gear et al., 2003; Fillingim and Gear 2004). While the underlying neurobiological mechanism of increased κ-opioid receptor sensitivity in women is still unclear, recent imaging studies suggest sex differences in μ-receptor concentration, binding affinity, and distribution in various brain areas, including the hypothalamus (Smith et al., 1998; Zubieta et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2006). Second, within women, there may be differential HPA axis responsivity associated with menstrual cycle-related changes in circulating sex hormone levels. Pre-clinical studies have demonstrated that estradiol injections increase levels of μ-receptors and circulating β-endorphins (Hammer and Bridges 1987; Hammer et al., 1993; Zhou and Hammer 1995; Quinones-Jenab et al., 1997). During periods of high estrogen concentration, i.e., late follicular and the mid-luteal phases, μ-opioid activity in women may be similar to men (Smith et al., 2006), but during periods of low estrogen levels, women exhibit lower activity in comparison to men (Zubieta et al., 2002; LeResche et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2006). Therefore, estrogen-mediated changes in endogenous opioid activity may impact hormonal responses to an acute dose of naltrexone by mediating HPA axis disinhibition. Heightened basal μ-opioid levels associated with a high estrogen menstrual phase may result in greater β-endorphin mediated inhibition of the hypothalamus. This increase in μ-opioid activity would result in direct competition for binding sites between endogenous μ-opioids, like β-endorphin, and naltrexone, ultimately decreasing hormonal response to drug administration. In contrast, lower endogenous μ-opioid activity, as seen during low estrogen menstrual phase or after menopause, may allow a low dose of naltrexone to readily disinhibit the HPA axis.

In the current study, a post-hoc examination of estimated menstrual cycle phase suggested some support for this notion: women deemed at a low estrogen phase (i.e., early/late luteal and early follicular, post-hysterectomy or post-menopausal) were more sensitive to the effects of naltrexone on ACTH and cortisol responsivity than women estimated at a high estrogen phase (i.e., mid/late follicular; mid luteal). While this post-hoc comparison is intriguing, these data were derived from self-report of last menstruation and medical history. Thus, future a priori investigations with verifications of sex hormone levels are needed before concluding that estrogen mediates HPA axis sensitivity to naltrexone amongst women.

Finally, there may be several genetic polymorphisms associated with sexually dimorphic responses to opioids and HPA axis function. For example, certain variants of melanocortin- and glucocorticoid-receptor genes have been associated with increased hormonal response to stress (Kumsta et al., 2007) and with greater k-opioid mediated analgesia (Mogil et al., 2003), respectively, in women as compared to men. Furthermore, in women but not men, polymorphisms in μ-opioid receptor (OPRM1) genes have been shown to be related to increased basal cortisol levels and the reinforcing value of nicotine (Bart et al., 2006; Ray et al., 2006). Further research focusing on potential differential allele expression in melanocortin-, glucocorticoid-, and opioid-receptor genes in men and women smokers may help elucidate sex differences in sensitivity to opioid antagonism.

In addition, our main findings may also have clinically relevant implications for naltrexone as a potential treatment for smoking cessation. It has been posited that HPA axis dysfunction may play an important role in tobacco cessation by impeding smokers’ physiological and psychological capacity to deal with the stress associated with the quitting process (al’Absi 2006). Several recent studies showed that smokers exhibited blunted ACTH and cortisol responses yet prolonged subjective distress after acute stress (Perkins et al., 1992; Kirschbaum et al., 1993; Kirschbaum et al., 1994; Tsuda et al., 1996; al’Absi et al., 2003; al’Absi et al., 2008; Childs and de Wit 2009). Furthermore, during early abstinence, degree of attenuated hormonal response has been shown to be predictive of relapse (al’Absi et al., 2004a; al’Absi et al., 2005; Shaw and al’Absi 2008). Extracting from the present study’s findings, it is possible that naltrexone may facilitate HPA axis activation in response to stress and effectively “normalize” the stress-response system. Given that attenuated diurnal cortisol in early abstinent smokers may predict relapse (al’Absi et al., 2004a), we speculate that naltrexone may be efficacious for smoking cessation (David et al., 2006; King et al., 2009) through its alleviation of tonic opioid inhibition of the HPA axis, thereby increasing diurnal cortisol levels and/or hormonal stress-responsivity in smokers.

Finally, in the exploratory study, cigarette smoking potentiated HPA axis hormone levels after naltrexone pretreatment in both men and women. This result confirmed our hypothesis that cigarette smoking and naltrexone would have an additive effect on ACTH and cortisol release. However, our hypothesis that women would show a heightened hormonal response to naltrexone pretreatment and smoking was not supported. These results, taken together, support preclinical data demonstrating that nicotine and opioid antagonists disinhibit the HPA axis through independent but potentially overlapping pathways resulting in net activation of the hypothalamus (Hill and Wynder 1974; Johnson et al., 1992; Matta et al., 1998; Fu et al., 2001; Valentino and Van Bockstaele 2001). To our knowledge, this study was the first to examine the acute interactive effects of naltrexone and smoking on the HPA axis. While it is possible that these effects may be similar in men and women, given the small sample for this exploratory aim, it is also possible that there was not sufficient statistical power to fully examine sex comparisons and future studies with larger sample sizes is warranted. In terms of potential clinical translation of these findings, we may speculate that cigarette smoking potentiation of naltrexone-induced increases in ACTH and cortisol may play a role in clinical response. Prior studies have shown that naltrexone alters subjective response to cigarette smoking, including increased dizziness and head rush, and reduced smoking desire (King and Meyer 2000; Epstein and King 2004). These data, along with the current study’s results showing naltrexone’s additive HPA axis responsivity to a cigarette may suggest that the optimal time course for initiation of naltrexone pharmacotherapy in smoking cessation treatment might be prior to the quit date. This timecourse may allow the patient to experience the interactive effects of the opioid antagonist with acute smoking, which may help extinguish reinforcing effects. However, caution should be taken to avoid over-interpretation of these pre-clinical data to clinical practice, as smokers in the current study were neither receiving nor desiring smoking cessation treatment.

Though the present study has several strengths, such as a highly controlled, stress-minimized environment and measures that were precisely timed to gather peak stress hormone responses in relation to naltrexone biotransformation (King et al., 2002), a few caveats are worthy of mention. First, the sample size was relatively small and the age range was limited to young and middle-aged adult smokers. Inclusion of a greater number of subjects in the smoking vs. non-smoking section of the study would allow a more comprehensive examination of sex differences in the ACTH and cortisol naltrexone-potentiated response to a single cigarette. Second, we did not collect adjunctive biological measures that may have permitted examination of potential mechanisms that underlie sex differences in HPA response to naltrexone. Future studies that measure levels of sex hormones and DNA would permit analysis of the effect of estrogen level and genotype on naltrexone response. Third, while this study demonstrates acute effects of naltrexone in the laboratory, these results may not translate to chronic dosing or clinical settings. Although Kosten et al. found evidence for continued HPA axis elevations during intermediate-term naltrexone treatment (Kosten et al., 1986c, b, a), long term changes in HPA reactivity during naltrexone treatment have not been studied. Finally, while administration of one cigarette of the participant’s preferred brand may be ecologically valid in terms of the naturalism of real-life smoking there may be confounds in terms of variability in nicotine exposure, other components in cigarettes, and nonspecific effects of visual, tactile, and olfactory smoking cues on response variables.

In summary, the present study demonstrated that an acute 50mg dose of naltrexone increases levels of ACTH and cortisol in female but not male smokers. These results may elucidate the potential sex differences underlying response to naltrexone in smoking cessation (Covey et al., 1999; King et al., 2006). Additionally, smoking a single cigarette potentiated naltrexone-increased ACTH and cortisol release for both men and women smokers. This finding provides further evidence for the interaction of the HPA axis and the endogenous opioid system in both acute smoking and nicotine dependence. Continued research on individual differences underlying opioid antagonist disinhibition of the HPA axis and on nicotine-opioid interactions may aid in our understanding of the neurobiological pathways underlying nicotine dependence and the potential refinement or development of efficacious medications for both sexes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the University of Chicago General Clinical Research Center (GCRC). Assistance was also provided by Sujata Patel, GCRC Core Lab Director and David Lynne, Research Assistant, in preparation and handling of blood samples and conducting cortisol assays, and to Dr. Neal Scherberg, Department of Medicine, Section on Endocrinology, for conducting and overseeing ACTH assays.

Role of funding source

This research was supported by NIH grants (R01-DAO016834, K08-AA00276, F31-AA15017) and a NCI Cancer Center Grant (P30-CA14599). This publication was also made possible by Grant Number UL1 RR024999 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the NIH and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The NIH, NIAAA, NCI, and NCRR had no further role in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors has any conflicts of interests to declare.

Contributors

Andrea King designed the study and provided supervision and oversight on data analyses, interpretation, and manuscript writing. Daniel Roche managed the literature searches, performed the statistical analysis, created the figures, and wrote the Introduction, Results, and Discussion sections. Emma Childs assisted in the writing of the manuscript and analysis of data. Alyssa Epstein wrote the first draft and assisted with editing of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aceto MD, Scates SM, Ji Z, Bowman ER. Nicotine’s opioid and anti-opioid interactions: proposed role in smoking behavior. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993;248:333–335. doi: 10.1016/0926-6917(93)90009-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical responses to psychological stress and risk for smoking relapse. Int J Psychophysiol. 2006;59:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Hatsukami D, Davis GL. Attenuated adrenocorticotropic responses to psychological stress are associated with early smoking relapse. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181:107–117. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Hatsukami D, Davis GL, Wittmers LE. Prospective examination of effects of smoking abstinence on cortisol and withdrawal symptoms as predictors of early smoking relapse. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004a;73:267–278. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Wittmers LE, Hatsukami D, Westra R. Blunted opiate modulation of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical activity in men and women who smoke. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:928–935. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31818434ab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Wittmers LE, Erickson J, Hatsukami D, Crouse B. Attenuated adrenocortical and blood pressure responses to psychological stress in ad libitum and abstinent smokers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;74:401–410. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al’Absi M, Wittmers LE, Ellestad D, Nordehn G, Kim SW, Kirschbaum C, Grant JE. Sex differences in pain and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical responses to opioid blockade. Psychosom Med. 2004b;66:198–206. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000116250.81254.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron JA, Comi RJ, Cryns V, Brinck-Johnsen T, Mercer NG. The effect of cigarette smoking on adrenal cortical hormones. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272:151–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bart G, LaForge KS, Borg L, Lilly C, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Altered levels of basal cortisol in healthy subjects with a 118G allele in exon 1 of the Mu opioid receptor gene. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2313–2317. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrendero F, Kieffer BL, Maldonado R. Attenuation of nicotine-induced antinociception, rewarding effects, and dependence in mu-opioid receptor knock-out mice. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10935–10940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10935.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrendero F, Mendizabal V, Robledo P, Galeote L, Bilkei-Gorzo A, Zimmer A, Maldonado R. Nicotine-induced antinociception, rewarding effects, and physical dependence are decreased in mice lacking the preproenkephalin gene. J Neurosci. 2005;25:1103–1112. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3008-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born J, Ditschuneit I, Schreiber M, Dodt C, Fehm HL. Effects of age and gender on pituitary-adrenocortical responsiveness in humans. Eur J Endocrinol. 1995;132:705–711. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1320705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DR, Goldberg LI. The use of quaternary narcotic antagonists in opiate research. Neuropharmacology. 1985;24:181–191. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(85)90072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childs E, de Wit H. Hormonal, cardiovascular, and subjective responses to acute stress in smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2009;203:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1359-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MR, Cohen RM, Pickar D, Weingartner H, Murphy DL. High-dose naloxone infusions in normals. Dose-dependent behavioral, hormonal, and physiological responses. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:613–619. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.04390010023003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaglen JV, Donald RA, Espiner EA, Livesey JH, Nicholls MG. Effect of naloxone on the hormone response to CRF in normal man. Endocr Res. 1985;11:39–44. doi: 10.3109/07435808509035423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covey LS, Glassman AH, Stetner F. Naltrexone effects on short-term and long-term smoking cessation. J Addict Dis. 1999;18:31–40. doi: 10.1300/J069v18n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryer PE, Haymond MW, Santiago JV, Shah SD. Norepinephrine and epinephrine release and adrenergic mediation of smoking-associated hemodynamic and metabolic events. N Engl J Med. 1976;295:573–577. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197609092951101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman P, Jr, Kreek MJ. Methadone-maintained patients. Effect of methadone on plasma testosterone, FSH, LH, and prolactin N.Y State. J Med. 1974;74:1970–1973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David S, Lancaster T, Stead LF, Evins AE. Opioid antagonists for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003086. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003086.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delitala G, Trainer PJ, Oliva O, Fanciulli G, Grossman AB. Opioid peptide and alpha-adrenoceptor pathways in the regulation of the pituitary-adrenal axis in man. J Endocrinol. 1994;141:163–168. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1410163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillo WS, Kong WM, Le Roux CW, Alaghband-Zadeh J, Jones J, Carter G, Mendoza N, Meeran K, O’Shea D. Cortisol-binding globulin is important in the interpretation of dynamic tests of the hypothalamic--pituitary--adrenal axis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2002;146:231–235. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1460231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein AM, King AC. Naltrexone attenuates acute cigarette smoking behavior. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2004;77:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2003.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farren CK, O’Malley S, Grebski G, Maniar S, Porter M, Kreek MJ. Variable dose naltrexone-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal stimulation in abstinent alcoholics: a preliminary study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:502–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fillingim RB, Gear RW. Sex differences in opioid analgesia: clinical and experimental findings. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:413–425. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Matta SG, Brower VG, Sharp BM. Norepinephrine secretion in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of rats during unlimited access to self-administered nicotine: An in vivo microdialysis study. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8979–8989. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-08979.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallucci WT, Baum A, Laue L, Rabin DS, Chrousos GP, Gold PW, Kling MA. Sex differences in sensitivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Health Psychol. 1993;12:420–425. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.12.5.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gear RW, Gordon NC, Heller PH, Paul S, Miaskowski C, Levine JD. Gender difference in analgesic response to the kappa-opioid pentazocine. Neurosci Lett. 1996a;205:207–209. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12402-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gear RW, Miaskowski C, Gordon NC, Paul SM, Heller PH, Levine JD. Kappa-opioids produce significantly greater analgesia in women than in men. Nat Med. 1996b;2:1248–1250. doi: 10.1038/nm1196-1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gear RW, Miaskowski C, Gordon NC, Paul SM, Heller PH, Levine JD. The kappa opioid nalbuphine produces gender- and dose-dependent analgesia and antianalgesia in patients with postoperative pain. Pain. 1999;83:339–345. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gear RW, Gordon NC, Miaskowski C, Paul SM, Heller PH, Levine JD. Sexual dimorphism in very low dose nalbuphine postoperative analgesia. Neurosci Lett. 2003;339:1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer RP, Jr, Bridges RS. Preoptic area opioids and opiate receptors increase during pregnancy and decrease during lactation. Brain Res. 1987;420:48–56. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90238-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer RP, Jr, Bogic L, Handa RJ. Estrogenic regulation of proenkephalin mRNA expression in the ventromedial hypothalamus of the adult male rat. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1993;19:129–134. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90157-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuser IJ, Gotthardt U, Schweiger U, Schmider J, Lammers CH, Dettling M, Holsboer F. Age-associated changes of pituitary-adrenocortical hormone regulation in humans: importance of gender. Neurobiol Aging. 1994;15:227–231. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(94)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill P, Wynder EL. Smoking and cardiovascular disease. Effect of nicotine on the serum epinephrine and corticoids. Am Heart J. 1974;87:491–496. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(74)90174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JR, Keely J, Naud S. Shape of the relapse curve and long-term abstinence among untreated smokers. Addiction. 2004;99:29–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston-Lyons D, Sarkar M, Kornetsky C. Nicotine and brain-stimulation reward: interactions with morphine, amphetamine and pimozide. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;46:453–457. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison KE, Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Swift RM, Colby SM, Gnys M, Niaura RS, Sirota AD. Effects of naltrexone with nicotine replacement on smoking cue reactivity: preliminary results. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;142:139–143. doi: 10.1007/s002130050872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes MD, Gianutsos G, Lal H. Effects of cholinergic agonists and antagonists on morphine-withdrawal syndrome. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1976;49:191–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00427289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EO, Kamilaris TC, Chrousos GP, Gold PW. Mechanisms of stress: a dynamic overview of hormonal and behavioral homeostasis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1992;16:115–130. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(05)80175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A, de Wit H, Riley RC, Cao D, Niaura R, Hatsukami D. Efficacy of naltrexone in smoking cessation: a preliminary study and an examination of sex differences. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:671–682. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Meyer PJ. Naltrexone alteration of acute smoking response in nicotine-dependent subjects. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:563–572. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00258-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AC, Schluger J, Gunduz M, Borg L, Perret G, Ho A, Kreek MJ. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis response and biotransformation of oral naltrexone: preliminary examination of relationship to family history of alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:778–788. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00416-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Wust S, Strasburger CJ. ‘Normal’ cigarette smoking increases free cortisol in habitual smokers. Life Sci. 1992;50:435–442. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90378-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Strasburger CJ, Langkrar J. Attenuated cortisol response to psychological stress but not to CRH or ergometry in young habitual smokers. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;44:527–531. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90162-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Scherer G, Strasburger CJ. Pituitary and adrenal hormone responses to pharmacological, physical, and psychological stimulation in habitual smokers and nonsmokers. Clin Investig. 1994;72:804–810. doi: 10.1007/BF00180552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Pirke KM, Hellhammer DH. Preliminary evidence for reduced cortisol responsivity to psychological stress in women using oral contraceptive medication. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1995a;20:509–514. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(94)00078-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Klauer T, Filipp SH, Hellhammer DH. Sex-specific effects of social support on cortisol and subjective responses to acute psychological stress. Psychosom Med. 1995b;57:23–31. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199501000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschbaum C, Kudielka BM, Gaab J, Schommer NC, Hellhammer DH. Impact of gender, menstrual cycle phase, and oral contraceptives on the activity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychosom Med. 1999;61:154–162. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein LC, Jamner LD, Alberts J, Orenstein MD, Levine L, Leigh H. Sex differences in salivary cortisol levels following naltrexone administration. J Appl Biobehav Res. 2000;5:144–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Kreek MJ, Ragunath J, Kleber HD. Chronic naltrexone effect on cortisol. NIDA Res Monogr. 1986a;67:362–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Kreek MJ, Ragunath J, Kleber HD. Cortisol levels during chronic naltrexone maintenance treatment in ex-opiate addicts. Biol Psychiatry. 1986b;21:217–220. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(86)90150-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TR, Kreek MJ, Ragunath J, Kleber HD. A preliminary study of beta endorphin during chronic naltrexone maintenance treatment in ex-opiate addicts. Life Sci. 1986c;39:55–59. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(86)90437-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ. Physiologic implications of methadone treatment. Proc Natl Conf Methadone Treat. 1973;2:824–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ. Medical complications in methadone patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1978;311:110–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1978.tb16769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Dodes L, Kane S, Knobler J, Martin R. Long-term methadone maintenance therapy: effects on liver function. Ann Intern Med. 1972;77:598–602. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-77-4-598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreek MJ, Ragunath J, Plevy S, Hamer D, Schneider B, Hartman N. ACTH, cortisol and beta-endorphin response to metyrapone testing during chronic methadone maintenance treatment in humans. Neuropeptides. 1984;5:277–278. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(84)90081-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan-Sarin S, Rosen MI, O’Malley SS. Naloxone challenge in smokers. Preliminary evidence of an opioid component in nicotine dependence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:663–668. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.7.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Hellhammer DH, Wust S. Why do we respond so differently? Reviewing determinants of human salivary cortisol responses to challenge. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:2–18. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Buske-Kirschbaum A, Hellhammer DH, Kirschbaum C. HPA axis responses to laboratory psychosocial stress in healthy elderly adults, younger adults, and children: impact of age and gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2004;29:83–98. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(02)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudielka BM, Hellhammer J, Hellhammer DH, Wolf OT, Pirke KM, Varadi E, Pilz J, Kirschbaum C. Sex differences in endocrine and psychological responses to psychosocial stress in healthy elderly subjects and the impact of a 2-week dehydroepiandrosterone treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1756–1761. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumsta R, Entringer S, Koper JW, van Rossum EF, Hellhammer DH, Wust S. Sex specific associations between common glucocorticoid receptor gene variants and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis responses to psychosocial stress. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:863–869. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunzel HE, Binder EB, Nickel T, Ising M, Fuchs B, Majer M, Pfennig A, Ernst G, Kern N, Schmid DA, Uhr M, Holsboer F, Modell S. Pharmacological and nonpharmacological factors influencing hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis reactivity in acutely depressed psychiatric in-patients, measured by the Dex-CRH test. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:2169–2178. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeResche L, Mancl L, Sherman JJ, Gandara B, Dworkin SF. Changes in temporomandibular pain and other symptoms across the menstrual cycle. Pain. 2003;106:253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin DH, Lake JR, Carter VA, Cunningham JS, Wilson OB. Naloxone precipitates nicotine abstinence syndrome in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993;112:339–342. doi: 10.1007/BF02244930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin DH, Lake JR, Payne MC, Short PE, Carter VA, Cunningham JS, Wilson OB. Nicotine alleviation of nicotine abstinence syndrome is naloxone-reversible. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996a;53:81–85. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)00202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin DH, Lake JR, Short PE, Blossman JB, Lawless BA, Schopen CK, Sailer EE, Burgess K, Wilson OB. Nicotine abstinence syndrome precipitated by an analog of neuropeptide FF. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996b;54:581–585. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(95)02279-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin del Campo AF, Dowson JH, Herbert J, Paykel ES. Effects of naloxone on diurnal rhythms in mood and endocrine function: a dose-response study in man. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1994;114:583–590. doi: 10.1007/BF02244988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matta SG, Fu Y, Valentine JD, Sharp BM. Response of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis to nicotine. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1998;23:103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(97)00079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meliska CJ, Gilbert DG. Hormonal and subjective effects of smoking the first five cigarettes of the day: a comparison in males and females. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;40:229–235. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90544-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson JH, Sholar MB, Goletiani N, Siegel AJ, Mello NK. Effects of low- and high-nicotine cigarette smoking on mood states and the HPA axis in men. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1751–1763. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelson JH, Goletiani N, Sholar MB, Siegel AJ, Mello NK. Effects of smoking successive low- and high-nicotine cigarettes on hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hormones and mood in men. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:749–760. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogil JS, Wilson SG, Chesler EJ, Rankin AL, Nemmani KV, Lariviere WR, Groce MK, Wallace MR, Kaplan L, Staud R, Ness TJ, Glover TL, Stankova M, Mayorov A, Hruby VJ, Grisel JE, Fillingim RB. The melanocortin-1 receptor gene mediates female-specific mechanisms of analgesia in mice and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4867–4872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730053100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley JE, Baranetsky NG, Wingert TD, Carlson HE, Hershman JM, Melmed S, Levin SR, Jamison KR, Weitzman R, Chang RJ, Varner AA. Endocrine effects of naloxone-induced opiate receptor blockade. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1980;50:251–257. doi: 10.1210/jcem-50-2-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naber D, Pickar D, Davis GC, Cohen RM, Jimerson DC, Elchisak MA, Defraites EG, Kalin NH, Risch SC, Buchsbaum MS. Naloxone effects on beta-endorphin, cortisol, prolactin, growth hormone, HVA and MHPG in plasma of normal volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1981;74:125–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00432677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz K, van de Borne PJ, Hausberg M, Cooley RL, Winniford MD, Davison DE, Somers VK. Cigarette smoking increases sympathetic outflow in humans. Circulation. 1998;98:528–534. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.6.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley SS, Cooney JL, Krishnan-Sarin S, Dubin JA, McKee SA, Cooney NL, Blakeslee A, Meandzija B, Romano-Dahlgard D, Wu R, Makuch R, Jatlow P. A controlled trial of naltrexone augmentation of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:667–674. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Grobe JE, Fonte C, Breus M. “Paradoxical” effects of smoking on subjective stress versus cardiovascular arousal in males and females. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1992;42:301–311. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90531-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF, Pomerleau CS. Cortisol response to a psychological stressor and/or nicotine. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1990;36:211–213. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(90)90153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau OF, Fertig JB, Seyler LE, Jaffe J. Neuroendocrine reactivity to nicotine in smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1983;81:61–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00439275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinones-Jenab V, Jenab S, Ogawa S, Inturrisi C, Pfaff DW. Estrogen regulation of mu-opioid receptor mRNA in the forebrain of female rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1997;47:134–138. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray R, Jepson C, Patterson F, Strasser A, Rukstalis M, Perkins K, Lynch KG, O’Malley S, Berrettini WH, Lerman C. Association of OPRM1 A118G variant with the relative reinforcing value of nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;188:355–363. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0504-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohleder N, Kirschbaum C. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in habitual smokers. Int J Psychophysiol. 2006;59:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarton E, Olofsen E, Romberg R, den Hartigh J, Kest B, Nieuwenhuijs D, Burm A, Teppema L, Dahan A. Sex differences in morphine analgesia: an experimental study in healthy volunteers. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1245–1254. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200011000-00018. discussion 1246A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluger JH, Ho A, Borg L, Porter M, Maniar S, Gunduz M, Perret G, King A, Kreek MJ. Nalmefene causes greater hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation than naloxone in normal volunteers: implications for the treatment of alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1430–1436. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt BL, Tambeli CH, Gear RW, Levine JD. Nicotine withdrawal hyperalgesia and opioid-mediated analgesia depend on nicotine receptors in nucleus accumbens. Neuroscience. 2001;106:129–136. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, Singer B, Wilkinson CW, McEwen B. Gender differences in age-related changes in HPA axis reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2001;26:225–240. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(00)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selzer ML, Vinokur A, van Rooijen L. A self-administered Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST) J Stud Alcohol. 1975;36:117–126. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1975.36.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw D, al’Absi M. Attenuated beta endorphin response to acute stress is associated with smoking relapse. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;90:357–362. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith YR, Stohler CS, Nichols TE, Bueller JA, Koeppe RA, Zubieta JK. Pronociceptive and antinociceptive effects of estradiol through endogenous opioid neurotransmission in women. J Neurosci. 2006;26:5777–5785. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5223-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith YR, Zubieta JK, del Carmen MG, Dannals RF, Ravert HT, Zacur HA, Frost JJ. Brain opioid receptor measurements by positron emission tomography in normal cycling women: relationship to luteinizing hormone pulsatility and gonadal steroid hormones. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:4498–4505. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.12.5351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland G, Stapleton JA, Russell MA, Feyerabend C. Naltrexone, smoking behaviour and cigarette withdrawal. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1995;120:418–425. doi: 10.1007/BF02245813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda A, Steptoe A, West R, Fieldman G, Kirschbaum C. Cigarette smoking and psychophysiological stress responsiveness: effects of recent smoking and temporary abstinence. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;126:226–233. doi: 10.1007/BF02246452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhart M, Chong RY, Oswald L, Lin PI, Wand GS. Gender differences in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis reactivity. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31:642–652. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ukai M, Holtzman SG. Suppression of deprivation-induced water intake in the rat by opioid antagonists: central sites of action. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1987;91:279–284. doi: 10.1007/BF00518177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino RJ, Van Bockstaele E. Opposing regulation of the locus coeruleus by corticotropin-releasing factor and opioids. Potential for reciprocal interactions between stress and opioid sensitivity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;158:331–342. doi: 10.1007/s002130000673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volavka J, Cho D, Mallya A, Bauman J. Naloxone increases ACTH and cortisol levels in man. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1056–1057. doi: 10.1056/nejm197905033001817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegratz I, Kutschera E, Lee JH, Moore C, Mellinger U, Winkler UH, Kuhl H. Effect of four oral contraceptives on thyroid hormones, adrenal and blood pressure parameters. Contraception. 2003a;67:361–366. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(03)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiegratz I, Kutschera E, Lee JH, Moore C, Mellinger U, Winkler UH, Kuhl H. Effect of four different oral contraceptives on various sex hormones and serum-binding globulins. Contraception. 2003b;67:25–32. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(02)00436-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins JN, Carlson HE, Van Vunakis H, Hill MA, Gritz E, Jarvik ME. Nicotine from cigarette smoking increases circulating levels of cortisol, growth hormone, and prolactin in male chronic smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1982;78:305–308. doi: 10.1007/BF00433730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winternitz WW, Quillen D. Acute hormonal response to cigarette smoking. J Clin Pharmacol. 1977;17:389–397. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1977.tb04621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong GY, Wolter TD, Croghan GA, Croghan IT, Offord KP, Hurt RD. A randomized trial of naltrexone for smoking cessation. Addiction. 1999;94:1227–1237. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.948122713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny JP. Morphine responses in humans: a retrospective analysis of sex differences. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001;63:23–28. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00186-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrindast MR, Faraji N, Rostami P, Sahraei H, Ghoshouni H. Cross-tolerance between morphine- and nicotine-induced conditioned place preference in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;74:363–369. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(02)01002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L, Hammer RP., Jr Gonadal steroid hormones upregulate medial preoptic mu-opioid receptors in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;278:271–274. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00175-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Dannals RF, Frost JJ. Gender and age influences on human brain mu-opioid receptor binding measured by PET. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:842–848. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Smith YR, Bueller JA, Xu Y, Kilbourn MR, Jewett DM, Meyer CR, Koeppe RA, Stohler CS. mu-opioid receptor-mediated antinociceptive responses differ in men and women. J Neurosci. 2002;22:5100–5107. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-12-05100.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]