Abstract

Objective

Angiotensin II (Ang II), a potent vasoconstrictor, affects the growth and development of hematopoietic cells. Mixed findings have been reported for the effects of ACE inhibitors on radiation-induced injury to the hematopoietic system. We investigated the consequences of different regimens of the ACE inhibitor captopril on radiation-induced hematopoietic injury.

Methods

C57BL/6 mice were either sham irradiated or were exposed to 60Co total body irradiation (0.6 Gy/min). Captopril was provided in the water for different time periods relative to irradiation.

Results

In untreated mice, the survival rate from 7.5 Gy was 50% at 30 days postirradiation. Captopril treatment for 7 days prior to irradiation resulted in radiosensitization with 100% lethality and a rapid decline of mature blood cells. In contrast, captopril treatment beginning 1 hour postirradiation and continuing for 30 days resulted in 100% survival, with improved recovery of mature blood cells and multilineage hematopoietic progenitors. In nonirradiated control mice captopril biphasically modulated Lin− marrow progenitor cell cycling. After 2 days, captopril suppressed G0-G1 transition and a greater number of cells entered a quiescent state. However, after 7 days of captopril treatment Linprogenitor cell cycling increased compared to untreated control mice.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that ACE inhibition affects hematopoietic recovery following radiation by modulating the hematopoietic progenitor cell cycle. The timing of captopril treatment relative to radiation exposure differentially affects the viability and repopulation capacity of spared hematopoietic stem cells and therefore can result in either radiation protection or radiation sensitization.

Keywords: hematopoietic syndrome, ionizing radiation, ACE inhibition, Angiotensin II, hematopoietic progenitor cells

Introduction

High dose total body irradiation (TBI), as the result of a nuclear accident, terrorist event, or as a clinical therapy for cancer, has significant hematopoietic toxicity. TBI destroys the hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow compartment that are critical for blood cell regeneration [1]. Following lethal TBI to the hematopoietic system, mortality in mice typically occurs between two and four weeks postirradiation. Death results from immune function impairment, infection, fever, and increased vascular permeability and microvascular hemorrhage in vital organs such as the brain and gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Of clinical importance, severe and prolonged cytopenia are a major cause of morbidity and mortality following myeloablation and HSC transplantation in the clinical setting [2].

The sensitivity of the hematopoietic system to radiation is believed to be due to the relatively rapid cycling times of both short-term and long-term reconstituting hematopoietic stem cells (ST-HSC and LT-HSC, respectively) [3, 4]. Compared with quiescent or slowly cycling cells, rapidly cycling cells are predisposed to increased DNA damage from radiation exposure, resulting in higher levels of apoptosis or senescence [5]. Agents that induce quiescence of the HSC population inhibit HSC apoptosis and senescence and thereby prevent radiation-induced stem cell pool exhaustion. Our laboratory has shown that the isoflavone genistein transiently arrests the LT-HSC in the G0/G1 phases of the cell cycle and reduces radiation-induced genotoxicity, senescence, and stem cell pool exhaustion [6, 7]. However, prevention of mortality from radiation-induced hematopoietic injury can also be achieved by agents that promote proliferation of the ST-HSC to replenish mature blood cells, although at the transient expense of reduced LT-HSC pools. The radiation protective agents granulocytecolony stimulating factor, interleukins, and thrombopoietin, for example, increase the proliferation and differentiation of ST-HSC and promote mature blood cell repopulation [4, 8, 9].

The renin-angiotensin system is critical for the regulation of blood pressure and blood volume homeostasis [10], but components of this system also regulate the proliferation and maturation of hematopoietic cells. Angiotensin II (Ang II) directly modulates the development and proliferation of hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPC) through Ang II receptors on the surfaces of these cells [11-14]. Plasma levels of Ang II are tightly regulated, and the protease angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) is required for the maturation of Ang II from its inactive precursor angiotensin I. Inhibition of ACE blocks the formation of active Ang II and can reversibly inhibit HSC proliferation in cell culture and in vivo [14-16].

The literature provides mixed reports for the effects of Ang II and ACE inhibitors on radiation-induced hematopoietic injury. Mice administered Ang II for 2-7 days beginning the day of irradiation exhibited increased 30-day survival and improved white blood cell recovery [17, 18], presumably through increased proliferation and self-renewal of spared multilineage hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Paradoxically, positive results have also been reported for hematopoietic radiation protection by ACE inhibitors. Early studies showed that the ACE inhibitor captopril failed to provide bone marrow protection in rats when administration was initiated 7 days prior to irradiation and continued for 28 days after irradiation [19]. However, perindopril, another ACE inhibitor, increased 30-day survival and protected ST-HSC when mice were treated for only 4 consecutive days beginning 2 days prior to irradiation through 2 days postirradiation [20]. This protection was shown to be due to the inhibition of Ang II maturation, because inhibitors of the Ang II type I receptor had similar protective effects on the hematopoietic system.

In this manuscript, radiosensitization and radioprotection, respectively, are defined as increased sensitivity or increased protection of cells, tissues, or organisms to gamma radiation, as a result of an agent being administered before and/or after radiation exposure. We demonstrate that captopril can have either radiosensitizing or radioprotective effects depending upon the time of administration relative to radiation exposure. Mice administered captopril for 7 consecutive days prior to irradiation exhibited radiosensitization, while treatments that began as early as 1 hour or 24 hours after irradiation were protective. The sensitizing versus protective effects of the two types of regimens was reflected in the severity of radiation-induced weight loss and in the repopulation rates of hematopoietic progenitor cells.

Materials and Methods

Experimental design

Female C57BL/6J mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) were 12–14 weeks of age (17.5-21.5 g) at the time of irradiation. Mice were housed in groups of four to five per cage in a facility accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. Animal rooms were maintained at 21 ± 2°C, 50% ± 10% humidity, and 12-hour light/dark cycle. Commercial rodent ration (Harlan Teklad Rodent Diet 8604, Harlan Laboratories, Madison, WI, USA) and acidified water (pH = 2.5-3.0), to control opportunistic infections [21] were freely available. All animal handling procedures were performed in compliance with guidelines from the National Research Council and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute (AFRRI, Bethesda, MD, USA).

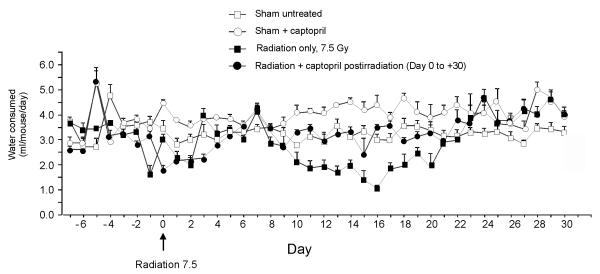

Naïve mice were randomized and assigned to groups that received either no treatment or various regimens of captopril treatment. We previously determined that 7.5 Gy TBI results in 50% lethality within 30 days (LD50/30) for C57BL/6J mice in AFRRI’s 60Co radiation facility [6]. As previously described [22], mice in the current experiments received TBI at 0.6 Gy/min. Control mice were sham irradiated. Captopril (USP grade, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in acidified water at 0.55g/L. A previous study established the stability of captopril in acidified water [23]. The effect of captopril on water intake was monitored for 30 days, with and without irradiation (Fig. 1). Captopril resulted in an increase in the daily volume of water consumed by nonirradiated mice (control 3.20 ± 0.03 ml/day versus captopril treatment 4.00 ± 0.20 ml/day). Radiation exposure resulted in a reduction in the average water consumption for approximately 2 weeks and was mitigated by captopril (Fig. 1). The average captopril consumption was calculated based on volumes of water consumed and body weights over the time course of the experiments. Nonirradiated mice had an effective dosage of 0.11 ± 0.01 mg/kg/day. In irradiated mice given captopril prior to irradiation, the average consumption was 0.10 ± 0.02 mg/kg/day. In mice treated with captopril after irradiation, the average consumption was 0.10 ± 0.05 mg/kg/day.

Figure 1. Effect of captopril on drinking water consumption.

Volume of water consumed was measured each day for the full time course of the experiment. The estimated volume of water consumed per mouse was calculated. Captopril was administered pre-irradiation from day −7 to day 0 (day of irradiation). Captopril administered postirradiation was from day 0 (beginning 1 hour after irradiation) to day +30.

For survival studies, mice were randomly assigned to one of seven groups. Two groups were sham irradiated (nonirradiated: handled/manipulated the same as irradiated mice): (i) no treatment (n = 20), (ii) captopril for 30 days (n = 20). Five groups received a single dose of 7.5 Gy TBI and were treated with or without captopril. The following groups received radiation (day 0 = day of irradiation): (iii) no treatment (n = 16), (iv) captopril for 7 days before irradiation through 30 days postirradiation (days −7 through +30) (n = 20), (v) captopril for days −7 through 0 (n = 20), (vi) captopril for days +1 (beginning 24 hours after irradiation) through +7 (n = 20), and (vii) captopril for days 0 (beginning 1 hour after irradiation) through +30 (n = 20). Survival was monitored for 30 days after TBI.

For hematological and tissue analysis, mice were randomized into one of five groups. Two groups were sham irradiated (nonirradiated): (i) no treatment, and (ii) captopril treated. The dose of irradiation for hematology or tissue analysis was either 7.5 Gy or 6 Gy, and groups were: (iii) no treatment, (iv) captopril for days −7 through 0, and (v) captopril for day 0 through the day of tissue harvest.

Mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital and blood was obtained by cardiac puncture, as previously described.[6] Complete blood counts (CBC) with differentials were obtained using a Baker Advia 2120 Hematology Analyzer (Siemens, Tarrytown, NY, USA). Separate mice were used at each time point (n = 5-6 per group). For determination of microhemorrhage, gross necropsies were performed on mice at the time of death or at the study termination end point (day 10 or day 14) (n = 6-10 per group). Organs, especially the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and the brain, were screened for hemorrhage, either petechiae or ecchymoses. Tissues with hemorrhage were immersion fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin with ionized zinc (Z-Fix®, Anatech Ltd, Battle Creek, MI, USA).

Hematopoietic progenitor colony-forming cell assays

Femoral bone marrow cells were isolated as previously described [22]. Unfractionated bone marrow cells were plated in multipotential methylcellulose culture medium (Methocult GF M3434; StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) at 1-5 × 104 cells per dish. Colonies derived from colony forming unit –granulocyte-erythroid-macrophage-megakaryocyte (CFU-GEMM), colony forming unit – granulocytic-macrophage (CFU-GM), blast forming unit -erythroid (BFU-E), and colony forming unit –macrophage (CFU-M) were scored after 8–12 days of incubation in a humidified environment, 5% CO2 as previously described [22]. Absolute numbers of clonogenic CFU progenitor cells per femur were calculated based on the total number of viable, nucleated cells per femur and on the number of colonies scored per number of cells plated.

Cell cycle analysis of Lin− and LSK+ cells

Lin− bone marrow cells were isolated using mouse Lin− cell MACSρ Cell Selection Kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (MACS; Miltenyi Biotec; Auburn, CA, USA). Cell cycle analysis was performed as previously described [22]. Lin− cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with PE-Sca-1 and APC-conjugated anti-mouse CD117 (cKit; antibodies from BD-Pharmingen, San Jose, CA USA). After surface staining was complete, Lin− cells were washed, fixed with 0.5 ml of 1.4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 1 hour at 4°C, and then incubated with an equal volume of 0.2% Triton-X overnight. Fixed, permeabilized Lin− cells were stained with Ki67- FITC (BD-Pharmingen) for 2 hours. Cells were washed and resuspended in staining buffer containing 2 mg/ml 7-aminoactinomycin-D (7AAD, Sigma). Lin− and gated LSK+ cells (Lin− Sca-1+cKit+) were analyzed for Ki67 expression and 7AAD incorporation by performing four color parameter sorting using a Coulter Elite flow cytometer (Coulter, Hialeah, FL, USA).

Statistical analysis

The Fisher’s exact test was used for analysis of survival data. Weight data were analyzed using one way ANOVA and Dunns test, using SigmaStat, 3.1 (Point Richmond, CA, USA). Hematology, clonogenic CFU assays, and cell cycle results are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance between the paired results was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak or Tukey postanalysis. A value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant. Mean survival time (MST) of decedents over 30 days was determined by the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, using Single Group statistics in the SigmaStat, 3.1 software.

Results

Effect of captopril regimens on 30-day survival following 7.5 Gy total body irradiation

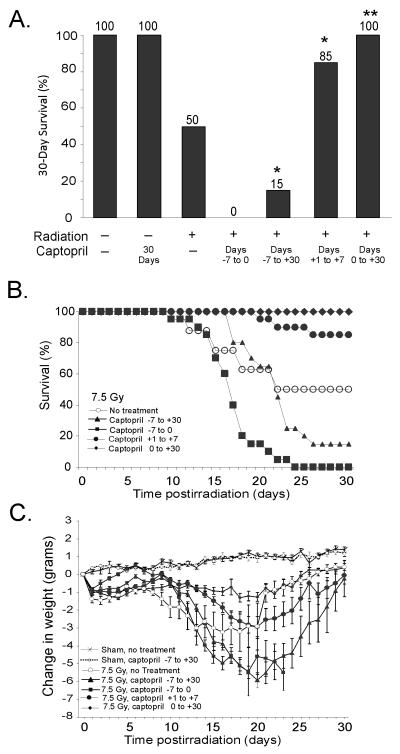

We previously showed that for female C57BL/6J mice the LD50/30 with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was 7.52 Gy (7.44, 7.59) in our 60Co facility [24]. We used this dose of irradiation to determine the effects of captopril treatment either before, after, or before and after irradiation. In untreated irradiated mice that received 7.5 Gy, 30-day survival was again 50%. The MST of decedents was 20 days (95% CI = 15 – 25) (Fig. 2A, B). The timing of mortality was consistent with acute hematopoietic injury. Administration of captopril prior to irradiation resulted in radiosensitization. When captopril administration began 7 days before irradiation (day −7) and continued until the day of irradiation (day 0), none (0%) of the mice survived, and the MST was 17 days (95% Confidence Inetrvals [CI] were 16 – 18). Mice pretreated with captopril for 7 days before irradiation and continuing through day 30 postirradiation (day +30) also exhibited radiosensitization, with 15% survival (p < 0.05 compared to untreated irradiated mice) and a MST of 21 days (95% CI, 20 – 22). In marked contrast, mice that received captopril only after irradiation exhibited a protective effect against hematopoietic injury. Thirty-day survival was 85% for mice that were administered captopril beginning 24 h after irradiation (day +1) and continuing for 7 days (p <0.05 from untreated irradiated mice). The MST of the three mice that died was 23 days (95% CI, 19 – 26). Mice administered captopril beginning 1 hour (day 0) after irradiation and continuing through day +30 exhibited 100% survival for 30 days (p < 0.001 compared to untreated irradiated mice).

Figure 2. Treatment of mice with captopril following high-dose irradiation is radioprotective whereas treatment prior to irradiation has a radiosensitization effect.

Mice were untreated or were administered captopril (0.1 mg/kg/day) in their drinking water before and/or after exposure to 7.5 Gy 60Co gamma total body irradiation (TBI). (A) The percentage of mice surviving at 30 days is shown. Results represent a total of 16-20 mice per group. * p < 0.05 from untreated irradiated mice. ** p < 0.001 from untreated irradiated mice. (B) Graph of 30 day survival. (C) Time-dependent change in body weight in nonirradiated control mice or mice that received captopril in their drinking water before and/or after exposure to 7.5 Gy 60Co TBI. Data represent the change in body weight ± standard error (SEM). n = 20 mice per group). Statistical findings are noted in the text.

The radiation sensitization or protection induced by captopril was reflected in the body weights of the mice (Fig. 2C). Radiation in untreated mice resulted in significant weight loss observable within 1 day postirradiation, with a nadir ~13-20 days postirradiation. Mice that received captopril prior to irradiation, either days −7 through 0 or days −7 through +30, exhibited greater weight loss than untreated irradiated mice. In mice administered captopril before irradiation, the reduction in body weight occurred for an extended time, and was significant between days 16–28 postirradiation (p < 0.05 compared to untreated irradiated mice). In contrast, mice treated with captopril after radiation exposure (days 0 through +30) maintained higher average body weights compared with untreated irradiated mice. The increased weight was significant between days 9-20 when compared to untreated irradiated mice (p < 0.05). Captopril treatment in the absence of radiation had no effect on body weight when compared to untreated control mice.

Captopril administration effects mature blood cell recovery following irradiation

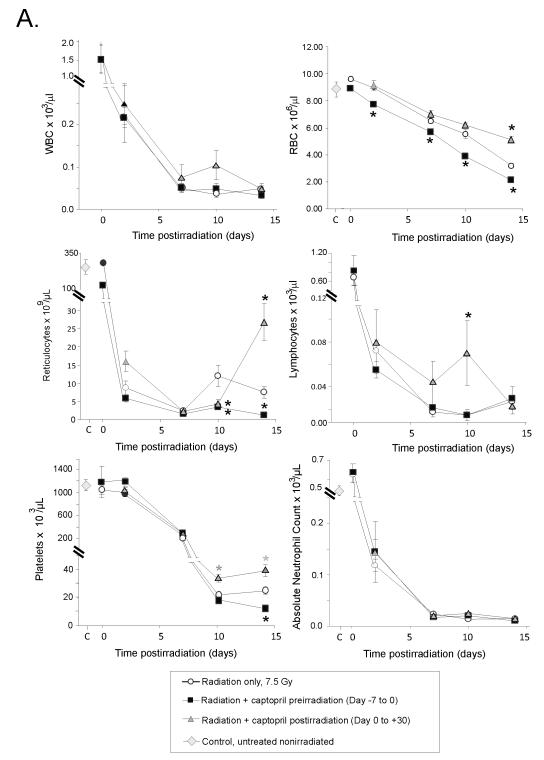

We hypothesized that protection from radiation-induced hematopoietic injury by captopril treatment postirradiation was associated with enhanced hematopoietic progenitor cell activity resulting in accelerated blood cell recovery. We examined the effects of two captopril regimens on hematopoietic recovery from 7.5 Gy TBI. Groups of mice received 1) no treatment, 2) captopril for 7 days prior to irradiation (day −7 through 0), or 3) captopril after irradiation beginning 1 hour postirradiation (day 0) and continuing for either 2 hours or 7,10, or 14 days after irradiation. CBC analyses were performed on separate groups of mice at 2 hours, and 7, 10, and 14 days postirradiation. A rapid decline of all mature blood cell types was observed following irradiation (Fig. 3A). In mice that received captopril prior to irradiation, a loss of red blood cells (RBC) occurred earlier and was more pronounced over the entire time course when compared to untreated irradiated mice. The decline in RBC was reflected by decreased levels in hematocrit and hemoglobin compared with untreated irradiated mice (data not shown). Reticulocyte recovery was also reduced in mice given captopril before irradiation and was significant on day 14 postirradiation. This modest decline in circulating erythroid cells is consistent with substantial radiosensitization of committed erythroid progenitor cells. Failure of platelet recovery was also observed on day 14 postirradiation in the group of mice receiving captopril from day 7 through day 0. In contrast, treatment of mice with captopril starting 1 hour after irradiation resulted in reduced radiation-induced loss of RBC, significant on day 14. Administration of captopril postirradiation also significantly improved reticulocyte recovery on day 14 and platelet recovery on days 10-14 postirradiation.

Figure 3. Effect of captopril administration on radioprotection.

Mice received no treatment or were administered captopril in their drinking water before (day −7 to day 0= day of irradiation) or after (day 0 [starting 1 hour after irradiation] to day 30) exposure to 7.5 Gy 60Co gamma total body irradiation. (Panel A) Peripheral blood white blood cells (WBC), red blood cells (RBC), reticulocytes, lymphocytes, platelets, and absolute neutrophils from irradiated mice, samples were taken at 2 hours (indicated on day 0), 2 7 10 or 14 days postirradiation. Control blood cell levels in untreated, nonirradiated mice are also indicated for blood cell types, except for lymphocytes (3.84 × 103 ± 0.4) and WBC (4.4 × 103 ± 0.5). Data show mean values ± SEM, n = 5-6 mice per group. * p < 0.05 compared with radiation alone cell counts at the same time point. (Panel B) Histological comparison of brain microhemorrhages in the subcortical cerebrum (100 × magnification) and cerebellar cortex (200 × magnification) of mice at day 14 postirradiation. Representative photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin stained tissue for mice treated with captopril prior to (upper panels with hemorrhage) or following (lower panels, normal brain) radiation exposure. The microhemorrhages are indicated by arrows and occur periventricularly in the subcortical cerebrum; ventricles (V) and corpus callosum (CC) are identified for orientation. Microhemorrhages also occured perivascularly in the cerebellar cortex extending from the white matter (WM) through the granular (G) and piriform/Purkinje (P) layers, abutting the molecular (M) layer.

Radiation-induced hematopoietic injury can lead to hemorrhage (petechiae and ecchymoses) and microhemorrhage in multiple organs, including the brain and GI tract [4]. Hemorrhages associated with acute radiation injury are ascribed to loss of platelets below a threshold level [25]. We examined the effects of 7.5 Gy 60Co on brain and GI hemorrhaging on days 10 and 14 postirradiation. No petechiae were detected on day 10. However, on day 14, 60% of untreated irradiated mice had grossly observable brain hemorrhages (4 were classified as mild; 2 were classified as minimal; n = 10). The sensitization or protection of blood cells by captopril was reflected by the presence or absence of gross hemorrhage and intracerebral microhemorrhages. All mice treated with captopril prior to irradiation (days −7 through 0), exhibited brain hemorrhages (4 mild, 6 minimal; n = 10) (Fig. 3B). In contrast, none of the mice treated with captopril postirradiation (starting on day 0) exhibited brain hemorrhages (n = 6). Evidence of gross vascular or microvascular hemorrhage in the GI tract was not observed in any group (data not shown).

Captopril effects on bone marrow recovery

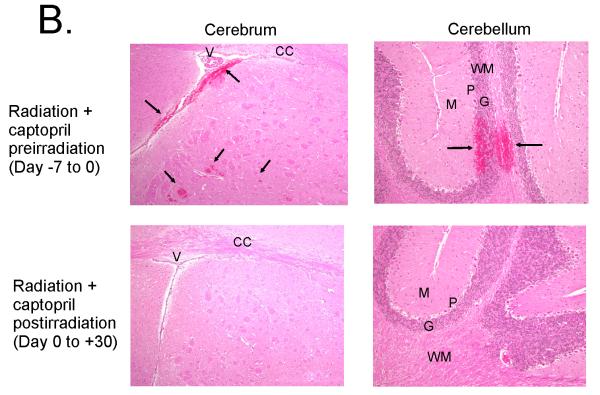

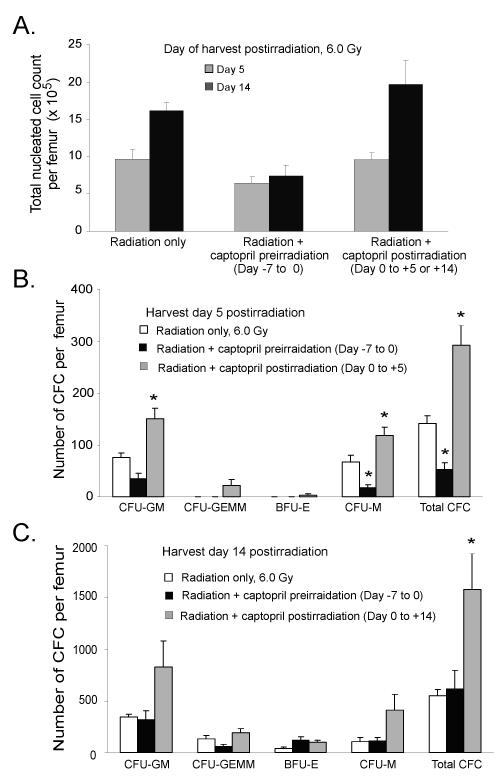

Radiation-induced stress can compromise the hematopoietic repopulation potential of HSC. Following high dose TBI there is an immediate proliferative demand on functionally spared LT- and ST-HSC to repopulate the ablated hematopoietic system [7]. Sustained hyperproliferation and differentiation signals can result in fewer HSC self-renewing divisions and can lead to exhaustion of the HSC pool and marrow repopulating failure. The molecular mechanisms preserving HSC require a balance between proliferation, differentiation, and self-renewal. These interrelated processes and mechanisms are important and not fully understood. Based on our postirradiation survival findings, we hypothesized that spared HSC are substantially less abundant and/or have an impaired repopulating potential in mice receiving captopril before irradiation as compared to mice treated with captopril postirradiation. To assess the kinetics of marrow repopulation, we examined total bone marrow cellularity and quantified assayable HPC production (in vitro CFU clonogenic assays) using marrow obtained from mice treated with radiation alone and in the two captopril-radiation regimens described above. Mice that received captopril before irradiation died with greater bone marrow progenitor/stem depletion that resulted in impaired marrow repopulation and decreased survival (radiosensitization). On day 14 postirradiation, mice receiving captopril prior to irradiation (days −7 through 0), exhibited reduced nucleated cellularity in the femoral bone marrow compared with mice in the untreated radiation only group. This indicated a gross deficit in total hematopoietic cell production in the marrow compartment (Fig. 4A). No significant differences in the number of total nucleated cells were observed between the radiation only group and the captopril postirradiation treatment groups.

Figure 4. Effect of captopril on nucleated cell bone marrow reconstitution in irradiated mice.

Mice were 1) untreated irradiated, 6.0 Gy total body irradiation (TBI-control group), 2) pretreated with captopril (0.1 mg/kg/day) for 7 consecutive days before irradiation, or 3) irradiated and then given captopril (0.1 mg/kg/day) for 14 consecutive days. At days 5 and 14 postirradiation, femoral bone marrow cells were collected. (Panel A) Total number of nucleated leukocytes cells per femur postirradiation. The number of assayable multilineage and lineage specific colony-forming progenitor cells were determined from bone marrow cells collected at day 5 (Panel B) and day 14 (Panel C) postirradiation. Multipotential (CFU-GEMM), myeloid (CFU-GM, CFU-M), and erythroid (BFU-E) bone marrow colony forming cells were determined. For all panels, results represent means ± SEM of six mice. * p < 0.05, compared with TBI-treated group; † p < 0.05 compared with the captopril pretreatment-treated group. For comparison purposes the bone marrow cellularity of untreated nonirradiated mice was 20.37 × 106 nucleated leukocytes/femur (data not shown).

Next, we characterized the types of hematopoietic progenitors present in each treatment group to assess the rapid loss of CFU and their subsequent expansion in the marrow compartment following radiation-induced hematopoietic injury. At day 5 but not at day 14 postirradiation, the number of total marrow CFU was significantly reduced in mice pretreated with captopril when compared with untreated irradiated mice (Fig. 4B, C). We also observed specific reductions in CFU-M populations. In contrast, mice treated with captopril postirradiation exhibited a significant increase in myeloid CFU progenitor cell production (CFU-GM and CFU-M) and total CFU at 5 days postirradiation (Fig. 4B). Trends were observed for improved recovery of CFU-GEMM and BFU-E, but these did not reach significance. At day 14 postirradiation, there was a significant increase in the total CFU in mice treated with captopril postirradiation compared with mice that received radiation alone (Fig. 4C). Trends toward increased levels of CFU-GM and CFU-M progenitor cell activity were also observed in mice that received captopril treatment postirradiation.

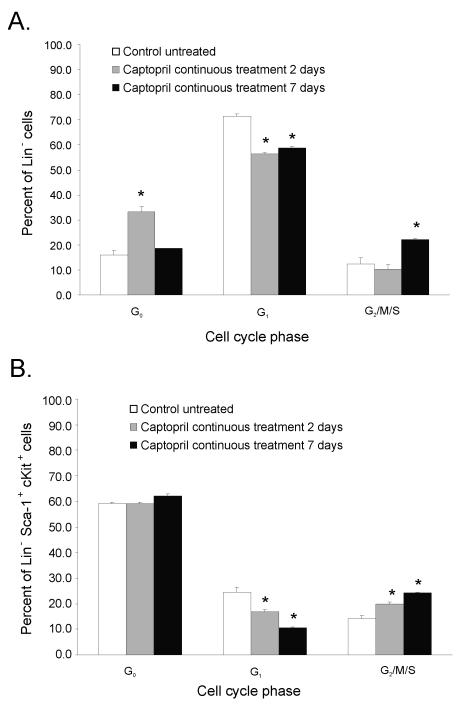

Effect of captopril on circulating hematopoietic cells and marrow-derived HPC

The results from mature blood cell counts and CFU assays suggested that captopril affected the sensitivity and/or recovery of hematopoietic cells and their precursors. Other investigators showed that Ang II directly regulates the growth and development of hematopoietic cells through angiotensin receptors on the surface of hematopoietic cells themselves [26, 27]. To investigate the effect of captopril on the HPC cell cycle profile, total Lin− and Lin−HPC (LSK+; Lin− Sca-1+ cKit+) femoral bone marrow cells were isolated from nonirradiated mice after 2 or 7 days of captopril treatment and stained with FITC-labeled Ki67 and 7ADD. Whereas 72% of bone marrow Lin− cells were actively in the cell cycle in control mice, the Lin− cells from mice that received 2 days of captopril treatment exhibited a significant decrease in the percentage of cells that were actively proliferating. This decrease was followed by a stronger G1 to G2/M/S transition after 7 days of captopril treatment (Fig. 5A). In contrast to what was observed for Lin− cells, the majority of the LSK+ remained in the G0 phase of the cell cycle after 2 days of captopril treatment. However, a similar G1 to G2/M/S cell cycle progression was detected in the LSK+ after 2 or 7 days of captopril treatment (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Captopril administration to nonirradiated control mice transiently dampens HPC bone marrow progenitor entry into the cell cycle (day 2) followed by a modest increase into G1 to G2 transition (day 7).

Mice were either untreated (control), or treated with captopril (0.1 mg/kg/day) for 2 or 7 days. Femoral bone marrow was obtained and Lin- cells were isolated from pooled femoral bone marrow cells by MACS selection. Cells were stained for Sca-1 and c-Kit cell surface expression. The cell cycle was determined by Ki67-FITC and 7AAD staining using multicolor flow cytometry. Data shown are the mean ± SEM of three separate experiments using pooled marrow from two mice per group, *p < 0.05 from control. (Panel A) Lin− cells (HPC enriched cells). (Panel B) Lin− Sca-1+cKit+ (LSK+, HSC enriched cells).

Discussion

Components of the renin-angiotensin system have been investigated for hematopoietic radiation protection because of the role of this system in hematopoietic cell regulation. Since ACE inhibitors are used extensively in the general population, it is critical to understand the effects of these drugs on radiation-induced hematopoietic injury, since radiotherapy is a common therapeutic modality for treating cancer, leukemia, and lymphoma [28, 29]. Paradoxically both ACE inhibitors and Ang II peptides have been shown to provide protection of the hematopoietic system [16, 18, 20]. Here, we demonstrate that treatment of mice with the ACE inhibitor captopril resulted in either radiation protection or radiation sensitization, depending upon the time of captopril administration. Captopril treatment in nonirradiated mice had a biphasic affect on the cycling of ST-HSC with transient quiescence after 2 days of treatment followed by increased proliferation by 7 days of treatment. Our experiments demonstrate that captopril administration beginning 1 hour or 24 hours after irradiation and continuing for 7 to 30 days increased survival. Therefore, captopril-induced radiation protection correlated with transient quiescence (increased G0) of the ST-HSC population and prevention of stem cell pool exhaustion. However, when captopril was initiated 7 days before irradiation and continued either to the time of irradiation or for an additional 30 days postirradiation, a significant increase in mortality was observed compared to untreated irradiated mice. In this case, radiation sensitization was correlated with increased cycling (increased G2/M) of the ST-HSC population at the time of radiation exposure.

HSC quiescence sustains long-term hematopoiesis by protecting the HSC pool from radiation-induced injury and from premature exhaustion under conditions of hematopoietic stress. On the other hand, premature entry of HSC into the cell cycle following radiation exposure exhausts the stem cell pool and leads to hematological failure [36]. The G2/M phases of the cell cycle as well as increased rate of cell cycling are associated with increased sensitivity to radiation [5, 7]. Examination of the response of HPC in nonirradiated mice indicated that two days of captopril administration resulted in HPC transiently withdrawing from the cell cycle with increased percentages of cells in the G0/G1 phases. However, in mice that received captopril for seven days, the HPC re-entered the cell cycle resulting in higher percentages of cells in the radiation-sensitive G2/M phases of the cycle. Therefore, exposure of the more rapidly cycling cells to radiation resulted in greater damage to the cells. This was reflected by the significant decreases in CFU of multilineage progenitor cells observed at 5 days postirradiation that ultimately resulted in increased hematopoietic failure. These findings suggest that HSC from captopril pretreated mice exhibit a higher activated state that is associated with a loss of HSC cell cycle quiescence and increased susceptibility to radiation therapy. This may have led to impaired long-term repopulating potential, hematopoietic exhaustion, bone marrow failure, and decreased survival.

Previous studies demonstrated that ACE inhibition is associated with decreased hematocrit, CD34+ cell apoptosis, and decreased cycling of hematopoietic stem cells [14, 16, 20, 30]. In some patient populations, captopril was shown to cause granulocytopenia [31, 32], aplastic anemia [33], and pancytopenia [34], highlighting the role of ACE activities in hematopoietic cell homeostasis. Inhibition of ACE prevents proteolytic inactivation of the hemoregulatory peptide N-Acetyl-Ser-Asp-Lys-Pro (AcSDKP), an inhibitor of hematopoietic stem cells cycling in vivo [16]. It was thought that AcSDKP regulation of the hematopoietic stem cell cycle could be the mechanism radiation protection by ACE inhibitors. However, administration of AcSDKP did not provide radiation protection, whereas Ang II receptor antagonists provided radioprotective effects similar to ACE inhibition [20], suggesting that blockade of Ang II maturation is the primary radioprotective effect of ACE inhibitors.

Cell culture experiments by others indicated that Ang II induces proliferation of ST-HSC and increased the formation of CFU-GM and CFU-GEMM colonies [11]. Our results demonstrate that radiation protection by administration of captopril after irradiation was correlated enhanced repopulation of bone marrow-derived CFU-GM and CFU-M clonogenic progenitor cells. In contrast, radiation sensitization due to the administration of captopril before irradiation was associated with decreased numbers of stem/progenitor cells (CFU-GEMM, CFU-GM, and CFU-M) in the bone marrow and subsequent dampened mature blood cell recovery. Thus our findings of radiation protection and sensitization in vivo are similar to in vitro findings for Ang II effects on specific progenitor populations. The differences between these effects may be due to indirect activities of ACE inhibition in vivo on hematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation.

It is of considerable importance that populations of erythrocytes, reticulocytes, and platelets, in addition to leukocytes, exhibited accelerated recovery in mice that received captopril postirradiation. Recent studies have demonstrated that the ability to rapidly reconstitute these lineages plays a key role in rescuing lethally irradiated recipients [35]. Upon reaching a critically low threshold platelet level or severe thrombocytopenia, hemorrhage develops in multiple organs and is a predictor of mortality [4]. The magnitude and duration of severe thrombocytopenia is hypothesized to be as important as severe neutropenia for survival from the radiation hematopoietic syndrome [25]. In our mouse irradiation model, it appears that the threshold level of severe thrombocytopenia was approximaetly 30,000 platelets/μl. Severe thrombocytopenia (below the threshold level) occurred on days 10 and 14 postirradiation in untreated irradiated mice (22,000 and 25,000 platelets/μl) and in the mice that received captopril before irradiation (15,000 and 12,000 platelets/μl). In both groups, reduced platelet levels were associated with gross macroscopic brain hemorrhage (petechiae & ecchymoses) as well as microscopic hemorrhages. In contrast, mice in the group that received captopril treatment only after irradiation did not have a period of severe thrombocytopenia and evidence of hemorrhage was not observed in any organ. Decreased platelet counts and increased brain hemorrhages observed in mice pretreated with captopril were associated with increased mortality. Conversely, mice administered captopril only postirradiation exhibited improved platelet counts and brain hemorrhage and death were mitigated.

Captopril has been proposed to function as an antioxidant [37], a free radical scavenger [38], and as an inhibitor of other proteases such as matrix metalloproteinases [39]. Captopril and other ACE inhibitors when administered postirradiation have been shown to modify a variety of late radiation-induced tissue injuries in the kidney, lung, skin, and heart [40, 41]. The mechanism of these agents in other tissue types is not completely known. Importantly, the enhanced marrow repopulation capacity observed in our in vivo radiation protective studies further supports our hypothesis that the necessary signals required to efficiently promote HSC repopulation may be potentiated through captopril treatment postirradiation. Irradiation of the bone marrow compartment before transplantation produces cytotoxic effects on the nonhematopoietic cellular constituents in the bone marrow “hematopoietic niche” as well on the hematopoietic cells [42-44]. Kopp et al. (45) reported that regeneration of damaged sinusoidal endothelial cells in the bone marrow niche is the rate-limiting step in hematopoietic regeneration from myelosuppressive therapy [45]. Although not the focus of this paper, captopril-induced radiation protection could possibly support enhanced nonhematopoietic cell repopulation resulting in accelerated reconstitution of the requisite hematopoietic supportive osteoblastic niche [46]. Furthermore, our findings suggest that the ability of captopril treatment in vivo to regulate the state of stem cell quiescence and the potential repopulating/regenerative ability of hematopoietic progenitors might have a useful application in clinical transplantation. On the other hand, patients undergoing ACE inhibitor therapy may be at a higher risk for impaired/delayed HSC engraftment and successful recovery of normal hematopoiesis. Further understanding of the mechanisms of action of captopril and other ACE inhibitors for radiation protection in these tissues will help in the development of future agents for prevention and mitigation of radiation-induced injuries.

Acknowledgments

We thank Harley Clinton for hematology support, and Asline Khnachar for histology support. Some of the authors are employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. §105 provides that ‘Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the United States Government.’ Title 17 U.S.C §101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employees of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties. The views in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views, official policy, or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Armed Forces Radiobiology Research Institute, Department of the Navy, Department of Defense or the U.S. Federal Government. This work was supported by: NIH grant HL73929 and a USUHS Research grant (RMD), DTRA grant H.10025_07_R (RMD and MRL), and NMRC ILIR grant 601152N.05580. 2130.A0704 (TAD).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure: There are no conflicts of interest for any of the authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Meder J, Michalowski A. Changes in cellularity and/or weight of mouse hemopoietic tissues as a measure of acute radiation effects. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 1980;28:9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Storb R. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation--yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)01020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wagemaker G. Heterogeneity of radiation sensitivity of hemopoietic stem cell subsets. Stem Cells. 1995;13(Suppl 1):257–260. doi: 10.1002/stem.5530130731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mouthon MA, Van der Meeren A, Vandamme M, Squiban C, Gaugler MH. Thrombopoietin protects mice from mortality and myelosuppression following high-dose irradiation: importance of time scheduling. Can J Physiol Pharmcol. 2002;80:717–721. doi: 10.1139/y02-090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Tamulevicius P, Wang M, Iliakis G. Homology-directed repair is required for the development of radioresistance during S phase: interplay between double-strand break repair and checkpoint response. Radiat Res. 2007;167:1–11. doi: 10.1667/RR0751.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Davis TA, Mungunsukh O, Zins S, Day RM, Landauer MR. Genistein induces radioprotection by hematopoietic stem cell quiescence. Int J Radiat Biol. 2008;84:713–726. doi: 10.1080/09553000802317778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Greenberger JS, Epperly M. Bone marrow-derived stem cells and radiation response. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2009;19:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Metcalf D. Hematopoietic cytokines. Blood. 2008;111:485–491. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-079681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Herodin F, Drouet M. Cytokine-based treatment of accidentally irradiated victims and new approaches. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:1071–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Stroth U, Unger T. The renin-angiotensin system and its receptors. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;33(Suppl 1):S21–S28. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199900001-00005. discussion S41-S23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rodgers K, Xiong S, Steer R, DiZerega G. Effect of Angiotensin II on Hematopoietic Progenitor Cell Proliferation. Stem Cells. 2000;18:287–294. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.18-4-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Zambidis ET, Park TS, Yu W, et al. Expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme (CD143) identifies and regulates primitive hemangioblasts derived from human pluripotent stem cells. Blood. 2008;112:3601–3614. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-144766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bahlmann FH, de Groot K, Mueller O, Hertel B, Haller H, Fliser D. Stimulation of endothelial progenitor cells: a new putative therapeutic effect of angiotensin II receptor antagonists. Hypertension. 2005;45:526–529. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000159191.98140.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Chisi JE, Wdzieczak-Bakala J, Thierry J, Briscoe CV, Riches AC. Captopril inhibits the proliferation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in murine long-term bone marrow cultures. Stem Cells. 1999;17:339–344. doi: 10.1002/stem.170339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chisi JE, Briscoe CV, Ezan E, Genet R, Riches AC, Wdzieczak-Bakala J. Captopril inhibits in vitro and in vivo the proliferation of primitive haematopoietic cells induced into cell cycle by cytotoxic drug administration or irradiation but has no effect on myeloid leukaemia cell proliferation. Brit J Haematol. 2000;109:563–570. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rousseau-Plasse A, Wdzieczak-Bakala J, Lenfant M, et al. Lisinopril, an angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitor, prevents entry of murine hematopoietic stem cells into the cell cycle after irradiation in vivo. Exp Hematol. 1998;26:1074–1079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ellefson DD, diZerega GS, Espinoza T, Roda N, Maldonado S, Rodgers KE. Synergistic effects of co-administration of angiotensin 1-7 and Neupogen on hematopoietic recovery in mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2004;53:15–24. doi: 10.1007/s00280-003-0710-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rodgers KE, Xiong S, diZerega GS. Accelerated recovery from irradiation injury by angiotensin peptides. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2002;49:403–411. doi: 10.1007/s00280-002-0434-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Moulder JE, Cohen EP, Fish BL, Hill P. Prophylaxis of bone marrow transplant nephropathy with captopril, an inhibitor of angiotensin-converting enzyme. Radiat Res. 1993;136:404–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Charrier S, Michaud A, Badaoui S, et al. Inhibition of angiotensin I-converting enzyme induces radioprotection by preserving murine hematopoietic short-term reconstituting cells. Blood. 2004;104:978–985. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].McPherson C. Reduction of Psuedomonas aeruginosa and coliform bacteria in mouse drinking water following treatment with hyrdochloric acid and chlorine. Lab Animal Care. 1963;13:737–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Davis TA, Clarke TK, Mog SR, Landauer MR. Subcutaneous administration of genistein prior to lethal irradiation supports multilineage, hematopoietic progenitor cell recovery and survival. Int J Radiat Biol. 2007;83:141–151. doi: 10.1080/09553000601132642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Escribano G, Torrado D, Torrado D. Stability study of an aqueous formulation of captopril at 1 mg/ml (Spanish) Farm Hosp. 2005;29:30–36. doi: 10.1016/s1130-6343(05)73633-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Day R, Barshishat-Kupper M, SR M, et al. Genistein Protects against Biomarkers of Delayed Lung Sequelae in Mice Surviving High Dose Total Body Irradiation. J Radiat Res. 2008;49:361–372. doi: 10.1269/jrr.07121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Stickney DR, Dowding C, Garsd A, et al. 5-androstenediol stimulates multilineage hematopoiesis in rhesus monkeys with radiation-induced myelosuppression. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1706–1713. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rodgers KE, Xiong S, Steer R, diZerega GS. Effect of angiotensin II on hematopoietic progenitor cell proliferation. Stem cells. 2000;18:287–294. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.18-4-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jokubaitis VJ, Sinka L, Driessen R, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (CD143) marks hematopoietic stem cells in human embryonic, fetal, and adult hematopoietic tissues. Blood. 2008;111:4055–4063. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ferdinand KC, Taylor C. The management of hypertension with angiotensin receptor blockers in special populations. Clin Cornerstone. 2009;9(Suppl 3):S5–S17. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(09)60014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Bommer WJ. Use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker therapy to reduce cardiovascular events in high-risk patients: part 2. Prev Cardiol. 2008;11:215–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7141.2008.00004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Glicklich D, Burris L, Urban A, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition induces apoptosis in erythroid precursors and affects insulin-like growth factor-1 in posttransplantation erythrocytosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:1958–1964. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1291958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].van Brummelen P, Willemze R, Tan W, et al. Captoprilassociated agranulocytosis. Lancet. 1980;1:150. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90629-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Casato M, Pucillo L, M L, et al. Granulocytopenia after combined therapy with interferon and angiotensin-convertingenzyme inhibitors: evidence for a synergistic hematological toxicity. Am J Med. 1995;99:386–390. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Israeli A, Or R, Leitersdorf E. Captopril-associated transient aplastic anemia. Acta Haematol. 1985;73:106–107. doi: 10.1159/000206292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gavras I, Graff L, Rose B, et al. Fatal pancytopenia associated with the use of captopril. Ann Intern Med. 1981;94:58–59. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-94-1-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Nakorn T Na, Traver D, Weissman IL, Akashi K. Myeloerythroid-restricted progenitors are sufficient to confer radioprotection and provide the majority of day 8 CFU-S. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1579–1585. doi: 10.1172/JCI15272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cheng T, Rodrigues N, Shen H, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell quiescence maintained by p21cip1/waf1. Science. 2000;287:1804–1808. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hosseinimehr SJ, Mahmoudzadeh A, Akhlagpour S. Captopril protects mice bone marrow cells against genotoxicity induced by gamma irradiation. Cell Biochem Funct. 2007;25:389–394. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chopra M, Scott N, McMurray J, et al. Captopril: a free radical scavenger. Brit J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;27:396–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb05384.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Williams RN, Parsons SL, Morris TM, Rowlands BJ, Watson SA. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase activity and growth of gastric adenocarcinoma cells by an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor in in vitro and murine models. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31:1042–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Moulder JE, Fish BL, Cohen EP. Treatment of radiation nephropathy with ACE inhibitors and AII type-1 and type-2 receptor antagonists. Curr Pharma Des. 2007;13:1317–1325. doi: 10.2174/138161207780618821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Moulder JE, Cohen EP. Future strategies for mitigation and treatment of chronic radiation-induced normal tissue injury. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2007;17:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ma J, Shi M, Li J, et al. Senescence-unrelated impediment of osteogenesis from Flk1+ bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells induced by total body irradiation and its contribution to long-term bone and hematopoietic injury. Haematologica. 2007;92:889–896. doi: 10.3324/haematol.11106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dominici M, Rasini V, Bussolari R, et al. Restoration and reversible expansion of the osteoblastic hematopoietic stem cell niche after marrow radioablation. Blood. 2009;114:2333–2343. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zhang J, Niu C, Ye L, et al. Identification of the haematopoietic stem cell niche and control of the niche size. Nature. 2003;425:836–841. doi: 10.1038/nature02041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kopp HG, Hooper AT, Avecilla ST, Rafii S. Functional heterogeneity of the bone marrow vascular niche. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1176:47–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Nilsson SK, Johnston HM, Whitty GA, et al. Osteopontin, a key component of the hematopoietic stem cell niche and regulator of primitive hematopoietic progenitor cells. Blood. 2005;106:1232–1239. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]