Abstract

Preference for a drug formulation is important in adherence to long-term medication for chronic illnesses such as osteoporosis. We investigated the preference for and acceptability of chewable tablet containing calcium and vitamin D (Calci Chew D3, Nycomed) compared to that of a sachet containing calcium and vitamin D3 (Cad, Will-Pharma). This open, randomised, cross-over trial was set up to compare the preference and acceptability of two calcium plus vitamin D3 formulations (both with 500 mg calcium and 400/440 IU vitamin D3), given twice a day in patients with osteoporosis. Preference and acceptability were assessed by means of questionnaires. Preference was determined by asking the question, which treatment the patient preferred, and acceptability was measured by scoring five variables, using rating scales. Of the 102 patients indicating a preference for a trial medication, 67% preferred the chewable tablet, 19% the sachet with calcium and vitamin D3, and 15% stated no preference. The significant preference for Calci Chew D3 (p < 0.0001) was associated with higher scores for all five acceptability variables. The two formulations were tolerated equally well. A significant greater number of patients considered the chewable tablet as preferable and acceptable to the sachet, containing calcium and vitamin D3. Trial registration: Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN18822358.

Keywords: Calcium, Drug preference, Osteoporosis, Treatment adherence, Vitamin D

Background

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterised by low bone density and changes in the micro-architecture resulting in an increased risk of fractures [1]. Osteoporosis is an important problem in the elderly, since fracture incidence increases with age. It is estimated that 40% of all 50 years old Caucasian women will sustain an osteoporotic fracture during their remaining lifetime [2]. These fractures may have major consequences, and particularly, hip and spine fractures are associated with increased morbidity and mortality [2–6].

Calcium and vitamin D are necessary for optimal development of the skeleton [7]. It has been shown in several studies that inadequate intake and absorption of calcium and vitamin D contributes to an increase in bone loss and increased risk of fractures [8–10]. The recommended intake of calcium in osteoporotic patients is at least 1000–1200 mg per day [11]. Recommendations for adequate daily intake of vitamin D are for elderly 400–800 IU; however, adults without adequate sun exposure require at least 800–1000 IU per day [7]. Dietary supplementation of calcium and vitamin D is believed to be beneficial for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Several studies have shown that dietary calcium and vitamin D supplementation not only increases bone mineral density but may also reduce the risk of fractures in elderly people [9, 11–13]. However, in other studies, no effect on fracture incidence was found [14, 15]. Furthermore, calcium and vitamin D supplements alone are insufficient to abolish the risk of fractures in osteoporosis, but are a necessary component of its treatment.

Bisphosphonates are important agents for fracture prevention and their effectiveness has been proven in several studies [16, 17]. Although supplementation of calcium and vitamin D3 cannot replace anti-resorptive therapy, it may increase the effectiveness of the treatment with bisphosphonates or oestrogen agonist/antagonist. Some data suggest a synergistic relation between a high calcium intake and anti-resorptive treatment for osteoporosis, since the increase in bone mass was greater when calcium was added to the anti-osteoporotic regimen [18]. In addition to yielding synergistic increments in bone mass, calcium and vitamin D supplementation may prevent hypocalcaemic reactions to inhibitors of bone resorption [19]. Moreover, calcium and vitamin D supplements are also necessary during treatment with bone formation stimulating agents such as recombinant parathyroid hormone 1–34 and 1–84 and strontium ranelate.

Therapeutic adherence can be subdivided into persistence and compliance [20]. Persistence refers to the length of time a patient continues drug treatment, while compliance describes how closely the patient maintains the recommended medication dosing schedule. Poor adherence to drug therapy remains a crucial problem in the long-term management of chronic diseases. During the treatment of osteoporosis, non-adherence is common: several studies have shown that 20–80% of patients discontinued the prescribed anti-osteoporotic medication (bisphosphonates, oestrogen and calcitonin) within 1 year [21–24]. This non-adherence has significant consequences; patients non-compliant with anti-osteoporosis treatment (such as bisphosphonates) have an increased fracture risk. [25, 26].

Adherence to prescribed medication may be influenced by many factors, such as adverse drug reactions, absence of symptoms, lack of motivation, socio-economic status and inconvenient packaging [24, 27]. Several strategies have been used to improve patient adherence. Research has shown that patients’ preferences for osteoporosis treatment are strongly influenced by the route of administration and that the willingness of a patient to continue long-term therapy is related to formulation, size and taste [28]. Therefore, it can be thought that initial preference for a drug formulation may be important in adherence to long-term medication for chronic illnesses such as osteoporosis.

The aim of this trial was to assess the preference for a formulation based on the identification of some of the factors that may influence compliance with the intake of calcium plus vitamin D3 supplements. The preference for and acceptability of a chewable tablet containing calcium and vitamin D3 and a sachet containing calcium and vitamin D3 were assessed in a randomised trial. This trial was part of a multi-national phase IV trial that was carried out in five European countries. The Belgian results have already been published [26]. This paper presents an analysis of the results of the trial in The Netherlands.

Methods

Study participants

This trial included patients visiting the outpatient clinic who required calcium and vitamin D supplementation as part of their anti-osteoporotic therapy. The patients’ physician included the patients for the trial after informed consent was obtained. The exclusion criteria were use of the trial medications during the past 6 months, any condition for which the trial medications are contra-indicated, such as hypercalcaemia, hypercalciuria, Zollinger–Ellison syndrome and nephrolithiasis, use of drugs known to interact with the trial medications (e.g., digoxin, tetracycline, fluoroquinolones, bisphosphonates, iron, sodium fluoride, diuretics, phenytoin, barbiturates, corticosteroids, levothyroxine, ion exchange resins, laxatives) and planned surgery during the 4-week study period. Pregnant, possibly pregnant, or breastfeeding women were excluded from the study. All patients gave written informed consent before being included in the study.

Study design

This randomised, open, cross-over clinical trial was conducted in four centres in The Netherlands: in Amsterdam, Hengelo, Heerlen and Delft. The trial, which was conducted between February 2003 and November 2003, was approved centrally by the Stichting Therapeutische Evaluatie Geneesmiddelen and by the local Ethics Committees.

Trial medication

The Calci Chew D3 chewable tablets (Nycomed) contained 1250 mg of calcium carbonate (equivalent to 500 mg elemental calcium) and 400 IU of cholecalciferol (equivalent to 10 μg vitamin D3). The sachet of calcium plus vitamin D3 (Cad, Will-Pharma) contained 1250 mg of calcium carbonate (equivalent to 500 mg elemental calcium) and 440 IU of vitamin D3.

The patients received both trial medications for 14 days, which was considered adequate for a patient to become familiar with the formulation and to assess the preference and acceptability. The patients received either the chewable tablet for 2 weeks followed by the sachet for 2 weeks or vice versa. One dose was given in the morning and one in the evening. The sachet was taken with 150 ml of water and dissolved before intake. The trial medications were delivered in the original sales packaging with the original package insert and with labels added for trial-specific details.

Number of subjects

The determination of required sample size was based on the primary endpoint: preference for one of the trial medications and on a previous trial with a similar design by Rees et al. [28]. The H0 hypothesis to be tested was that the preference for either trial medication was 50%. The alternative hypothesis was that the preference for either trial medication was 60%. According to binomial theory, inclusion of 200 subjects would result in a power of 78% in the statistical analyses.

Visit procedures

At the first visit, the patients signed the informed consent form, entry criteria were evaluated, and demographic data, smoking and drinking habits, concomitant illness including history of fractures, osteopenia and osteoporosis and use of concomitant drugs were recorded. Patients were randomised by block randomisation, stratified per centre and received either medication A (Calci Chew D3) or B (sachet with calcium and vitamin D3) and were asked to return 14 days later. At visit 2, the patients returned the unused trial doses for drug accountability and received the package with the second trial medication. The patients completed the acceptability questionnaire, and all adverse events that had occurred during period 1 were recorded. At visit 3, i.e., 14 days later, unused trial doses were returned, the subjects completed the acceptability and preference questionnaires and all adverse events were again recorded.

Questionnaires

Preference was assessed at visit 3 when the subjects were asked to indicate the preferred trial medication. Patients were asked to choose between the following options: preference for the first treatment, the second treatment or no preference.

Acceptability

At visits 2 (day 14) and 3 (day 28), the subjects were asked to assess five variables using the 11-point rating scales: removing the dose from the container (very difficult (0)–very easy (10)), taking the dose (very difficult (0)–very easy (10)), taste (very bad (0)–very good (10)), time spent taking the dose (very troublesome (0)–no problem at all (10)) and general convenience of taking the dose (very difficult (0)–very easy (10)).

Safety

Adverse events were defined as either events that occurred after informed consent was given or events present at baseline that became progressively worse during the study period. Adverse events were evaluated and recorded at every visit.

Statistics

A test level of α = 5% was used to determine statistical significance. Statistical analyses were performed per protocol (PP). The primary endpoint, preference for a trial medication, was analysed by a logistic regression model. Preference for treatment A (yes/no) was the dependent variable; sequence of treatment was the independent variable. The intercept in the model provided an estimate of the difference between treatments, sequence of treatment was an estimate of the sequence effect. The secondary efficacy endpoints were analysed using a linear mixed model with treatment and period as fixed effects and subjects as random effect. The primary and secondary endpoints were summarised for various subgroups: sex (male/female), age (≤/>65 years), smoking >10 units of tobacco per day, daily intake of alcohol (yes/no), history of osteoporosis (yes/no), history of osteopenia (yes/no) and history of fractures within the last 10 years (yes/no). SAS, version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA) was used in all statistical analyses.

Results

Study participants

A total of 102 patients participated in the trial. Since the trial had to be finished by a fixed deadline and in order not to delay overall international completion of the trial, less than 200 patients were enrolled in The Netherlands. Demographic and baseline data are presented in Table 1. Of the 102 patients, 88% were women and 12% were men. The mean age was 66 years (range 34–83). There was a history of osteopenia in 13 patients (13%), osteoporosis in 66 (65%) and fractures in 18 (18%). Concomitant drug use was reported by 99 patients (97%) and concomitant illness by 102 patients (100%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants

| Characteristics | All (n = 102) |

|---|---|

| Male | 12 (12%) |

| Female | 90 (88%) |

| Mean age, years (range) | 66 (34–83) |

| Smoking | 16 (16%) |

| Daily alcohol | 27 (26%) |

| History of osteoporosisa | 66 (65%) |

| History of osteopeniaa | 13 (13%) |

| History of fractures | 18 (18%) |

| Concomitant drugs | 99 (97%) |

| Concomitant illness | 102 (100%) |

aHistory of osteoporosis and osteopenia was defined by the physician

In total, 86 patients completed the 4-week trial period; 11 subjects discontinued due to adverse events and five discontinued for other reasons.

Compliance

Treatment compliance was good for both preparations; the mean number of days on drug was 12.8 days for the chewable tablet and 13.5 days for the sachet.

Preference

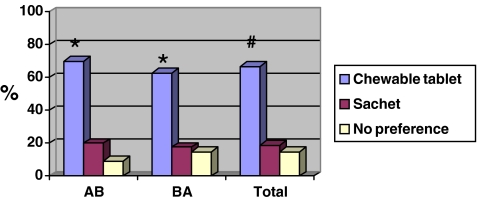

Preference data are available for 96 patients: 67% (64 patients) preferred the chewable tablet, 19% (18 patients) preferred the sachet and 15% (14 patients) had no preference (Fig. 1). Of the 82 patients stating a preference, 78% therefore preferred the chewable tablet (p < 0.0001). The sequence of treatments had no influence on preference (p = 1.000). The chewable tablet was preferred to the sachet by relatively more male 83% (n = 10/12) than female patients 64% (n = 54/84) and by the younger patients (82% versus 56%). For the other demographic characteristics (smoking and a history of osteoporosis, osteopenia or fracture), the percentages of preference were similar (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Preferences (%) of study participants (n = 96). A chewable tablet, Calci Chew D3; B sachet of calcium and vitamin D3 CAD. Single asterisk indicates p < 0.0008 versus sachet with calcium and vitamin D3. Number sign indicates p < 0.0001 versus sachet with calcium and vitamin D3. The “no preference” patients were ignored in the statistical analysis

Table 2.

Preference results, distributed by demographic characteristics and risk factors

| Variable | All Patients (N = 96) | Preferencea | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chewable tablet, calcium ± vitamin D3 (n = 64) | Sachet, calcium ± vitamin D3 (n = 18) | None (n = 14) | ||

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 84 | 54 (64.3%) | 17 (20.2%) | 13 (15.5%) |

| Male | 12 | 10 (83.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Age group | ||||

| ≤65 year | 39 | 32 (82.1%) | 4 (10.3%) | 3 (7.7%) |

| >65 year | 57 | 32 (56.1%) | 14 (24.6%) | 11 (19.3%) |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Smoke >10 U/day | ||||

| Yes | 14 | 9 (64.3%) | 3 (21.4%) | 2 (14.3%) |

| No | 82 | 55 (67.1%) | 15 (18.3%) | 12 (14.6%) |

| Drink alcohol daily | ||||

| Yes | 26 | 15 (57.7%) | 5 (19.2%) | 6 (23.1%) |

| No | 70 | 49 (70.0%) | 13 (18.6%) | 8 (11.4%) |

| Disease history | ||||

| Osteoporosis | ||||

| Yes | 62 | 43 (69.4%) | 10 (16.1%) | 9 (14.5%) |

| No | 34 | 21 (61.8%) | 8 (23.5%) | 5 (14.7%) |

| Osteopenia | ||||

| Yes | 12 | 8 (66.7%) | 3 (25.0%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| No | 84 | 56 (66.7%) | 15 (17.9%) | 13 (15.5%) |

| Fracture | ||||

| Yes | 15 | 9 (60.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 4 (26.7%) |

| No | 81 | 55 (67.9%) | 16 (19.8%) | 10 (12.3%) |

Missing data not included

aPercentages may not total 100 due to rounding

Acceptability

The scores for the secondary endpoints, i.e., the five acceptability variables (removing the dose from the container, taking the dose, taste, time spent taking the dose and general convenience of taking the dose), were consistently higher for the chewable tablet calcium and vitamin D3 than for the sachet with calcium and vitamin D3 (Table 3). The difference between the chewable tablet and the sachet was statistically significant (p < 0.0001) for all five variables. The distribution of acceptability, with higher scores for the chewable tablet, was independent of gender or age (data not shown).

Table 3.

Acceptability, questionnaire response, mean estimates per acceptability variablea

| Mean estimate (±SD) | Chewable tablet, calcium ± vitamin D3 | Sachet, calcium ± vitamin D3 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ease of removing the dose from container | 9.1 (±1.2) | 7.9 (±2.1) | <0.0001 |

| Ease of taking the dose | 9.0 (±1.6) | 8.4 (±1.7) | 0.0035 |

| Perception of taste as pleasant | 8.7 (±1.6) | 7.6 (±2.4) | <0.0001 |

| Time to take the dose | 9.1 (±1.4) | 8.4 (±1.9) | 0.0036 |

| Overall convenience of taking the dose | 9.0 (±1.6) | 8.3 (±1.9) | 0.0023 |

aThe 5-variable acceptability questionnaire used the following widely accepted but not validated 11-point rating scales: removing the dose from the container (scale: 0 = very difficult to 10 = very easy), taking the dose (scale: 0 = very difficult to 10 = very easy), taste (scale: 0 = very bad to 10 = very good), time spent taking the dose (scale: 0 = very troublesome to 10 = no problem at all) and general convenience of taking the dose (scale: 0 = very difficult to 10 = very easy).

Safety evaluation

In general, adverse events were equally distributed between treatment groups: this pertained to the total number of adverse events, the most frequent adverse events, their severity and causality.

A total of 61 adverse events were reported: of these, 45 were considered probably or possibly related to the trial medication: 23 events in 21 patients during treatment with the chewable tablet and 22 events in 20 patients during treatment with the sachet. (Table 4) Most of the adverse events were non-serious, with a severity ranging from mild to moderate. The most frequently reported adverse events were gastro-intestinal (93%), including constipation, nausea, diarrhoea, dyspepsia and flatulence. These adverse events are well known during treatment with calcium salts. Two serious adverse events were reported (one patient had a gastric haemorrhage and one patient experienced an aggravation of her rheumatoid arthritis), but both were felt to be unrelated to the trial medication. Eleven patients withdrew from the trial due to one or more adverse events; two patients discontinued during both treatment periods. The most frequent adverse event leading to discontinuation were constipation (n = 4), nausea (n = 3) and stomach discomfort (n = 2).

Table 4.

Prevalence of probably or possibly treatment-related adverse events (AEs) by organ system

| Adverse events | Chewable tablet, calcium ± vitamin D3 (N = 102) | Sachet, calcium ± vitamin D3 (N = 97) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | AE | n (%) | AE | |

| All | 21 (21) | 23 | 20 (21) | 22 |

| Gastro-intestinal disorders (total) | 20 (20) | 21 | 19 (20) | 21 |

| Constipation | 9 (9) | 9 | 5 (5) | 5 |

| Nausea | 5 (5) | 5 | 6 (6) | 6 |

| Upper abdominal pain | 1 (1) | 1 | 1 (1) | 1 |

| Flatulence | 2 (2) | 2 | 2 (2) | 2 |

| Eructation | 0 (0) | 0 | 2 (2) | 2 |

| Diarrhoea NOS | 0 (0) | 0 | 4 (4) | 4 |

| Dyspepsia | 1 (1) | 1 | 1 (1) | 1 |

| Stomach discomfort | 2 (2) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Aphthous stomatitis | 1 (1) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Nervous system disorders | ||||

| Headache | 1 (1) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Renal and urinary disorder (total) | ||||

| Abnormal urine NOS | 0 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 |

| Skin disorders | ||||

| Pruritus | 1 (1) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 |

N number of subjects exposed to treatment, n number of subjects with event, AE number of adverse events, % percentage of subjects with adverse event (n) per subjects exposed (N)

Discussion

The purpose of the present trial was to compare the preference and acceptability of a chewable tablet containing calcium and vitamin D3 with that of the comparator, a sachet containing calcium and vitamin D3. The results of the trial support the general preference for the chewable tablet of calcium and vitamin D3 versus the sachet with calcium and vitamin D3. Moreover, the five acceptability scores were all significantly higher for the chewable tablet than for the calcium and vitamin D3 sachet. Our results are comparable with those of two earlier studies [28, 29]. In these randomised, cross-over trials 72–78% of patients preferred the chewable calcium and vitamin D3 supplements.

Poor adherence to osteoporotic treatment, e.g., bisphosphonates, results in insufficient effect of reducing fracture risk. Also, for calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation, it is reasonable to believe that better persistence translates into greater efficacy. Dawson-Hughes et al. [30] demonstrated the importance of an ongoing intake of calcium and vitamin D, since the beneficial effect on bone mineral density obtained in elderly men and women did not persist after discontinuation of the supplementation. Moreover, the bone-turnover rates returned to their original higher rates after discontinuation [30]. They concluded that intermittent use of calcium and vitamin D provides limited long-term skeletal benefit and recommended continued intake of calcium and vitamin D supplements.

Osteoporosis is a major problem, especially in the elderly. Low calcium intake and vitamin D insufficiency are common in elderly people due to insufficient calcium and vitamin D absorption and diminished physical activity [8, 13]. Calcium and vitamin D supplements have been shown to decrease fracture risk in patients who are deficient for both [9, 12] but not in patients who have no calcium or vitamin D deficiency [31]. Therefore, continued calcium and vitamin D supplementation is a necessary component of anti-osteoporotic treatment in the elderly. However, adherence to treatment decreases with older age because of forgetfulness, inability to handle the packaging, multimorbidity and multimedication [27, 32]. Besides adherence to therapy, compliance with the prescribed dosage is also often inadequate: older patients often take the medication less frequently than prescribed [24, 27] It is reasonable to conclude that a more convenient formulation and less frequent administration would lead to improved compliance in the elderly [8, 33].

An important reason for patients to discontinue treatment is the appearance of side effects [34, 35]. In our trial, the total number of adverse events, the most frequent adverse events and their causality were equally distributed between treatment groups and the majority of the events were non-serious with a severity ranging from mild to moderate [36]. Overall, the chewable tablet of calcium and vitamin D3 and the sachet containing calcium and vitamin D3 were well tolerated, and the gastro-intestinal side effects were comparable between the two groups.

There are several limitations of this study. First, less than 200 patients were included. Nevertheless, the study had enough power to show the above mentioned significant differences between groups because the results were stronger than hypothesised in the original rather conservative power calculation. Second, it is not known which percentage of patients received one of the studied treatments in the past (more than 6 months before the trial started). It could be that some patients were already familiar with one of the treatments; however, this probably would not have influenced the outcome. Third, in this study only two forms of calcium suppletion were compared. However, these are the formula most described, and therefore, the results are believed to be of great interest for daily practise. Finally, the 2-week treatment periods were considered sufficient to enable a subject to assess the variables. The high number of subjects that completed the trial (91%) indicates that the intention to make participation convenient for the subjects was achieved. It can be suggested that an initial strong preference for one calcium and vitamin D supplementation above the other might have consequences for long-term treatment. However, the short-time period is a limitation when persistence should be analysed.

In conclusion, the chewable tablet containing calcium and vitamin D3 was generally preferred to the sachet containing calcium and vitamin D3. In line with these results, the chewable tablet was found to be more acceptable than the sachet. The tolerability was similar for the two formulations.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who participated in the trial for their time and interest.

Disclosures

None

Competing interests

This research was sponsored by Nycomed Group AS/Roskilde, Denmark.

Authors’ contributions

The contributing investigators were Prof. Dr. P Geusens, Maastricht University Hospital, Maastricht; Dr. F.N.R. van Berkum, Twente regional hospitals, Hengelo; Dr. H.H.M.L. Houben, Maasland Hospital, Sittard; Dr. M.C.M. Jebbink, Reinier de Graaf Gasthuis, Delft and Prof Dr. W.F. Lems, VU Medical Centre, Amsterdam. All of the authors were involved with the design of the study, interpretation of results and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Nycomed was responsible for the data collection and analysis.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Turner CH. Biomechanics of bone: determinants of skeletal fragility and bone quality. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:97–104. doi: 10.1007/s001980200000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doherty DA, Sanders KM, Kotowicz MA, Prince RL. Lifetime and five-year age-specific risks of first and subsequent osteoporotic fractures in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:16–23. doi: 10.1007/s001980170152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Browner WS, Pressman AR, Nevitt MC, Cummings SR. Mortality following fractures in older women. The study of osteoporotic fractures. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:1521–1525. doi: 10.1001/archinte.156.14.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper C, Atkinson EJ, Jacobsen SJ, O'Fallon WM, Melton LJ., III Population-based study of survival after osteoporotic fractures. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137:1001–1005. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper C. The crippling consequences of fractures and their impact on quality of life. Am J Med. 1997;103:12S–17S. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(97)90022-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson RE, Goodman MJ, Hornbrook MC, Eldredge MB. The impact of increasing patient prescription drug cost sharing on therapeutic classes of drugs received and on the health status of elderly HMO members. Health Serv Res. 1997;32:103–122. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:266–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra070553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ensrud KE, Duong T, Cauley JA, Heaney RP, Wolf RL, Harris E, Cummings SR. Low fractional calcium absorption increases the risk for hip fracture in women with low calcium intake study of osteoporotic fractures research group. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:345–353. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-5-200003070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Recker RR, Hinders S, Davies KM, Heaney RP, Stegman MR, Lappe JM, Kimmel BD. Correcting calcium nutritional deficiency prevents spine fractures in elderly women. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11:1961–1966. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Riggs BL, Melton LJ, III, O'Fallon WM. Drug therapy for vertebral fractures in osteoporosis: evidence that decreases in bone turnover and increases in bone mass both determine antifracture efficacy. Bone. 1996;18(3 Suppl):197S–201S. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(95)00502-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Krall EA, Dallal GE. Effect of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on bone density in men and women 65 years of age or older. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:670–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709043371003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapuy MC, Arlot ME, Duboeuf F, Brun J, Crouzet B, Arnaud S, Delmas PD, Meunier PJ. Vitamin D3 and calcium to prevent hip fractures in the elderly women. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1637–1642. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199212033272305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapuy MC, Pamphile R, Paris E, Kempf C, Schlichting M, Arnaud S, Garnero P, Meunier PJ. Combined calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation in elderly women: confirmation of reversal of secondary hyperparathyroidism and hip fracture risk: the Decalyos II study. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13:257–264. doi: 10.1007/s001980200023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson RD, LaCroix AZ, Gass M, Wallace RB, Robbins J, Lewis CE, Bassford T, Beresford SAA, Black HR, Blanchette P, Bonds DE, Brunner RL, Bryski RG, Caan B, Cauley JA, Cheblowski RT, Cummings SR, Granek I, Hays J, Heiss G, Hendrix SL, Howard BV, Hsia J, Hubbell FA, Johnson KC, Judd H, Kotchen JM, Kuller LH, Langer RD, Lasser NL, Limacher MC, Ludlam S, Manson JE, Margolis KL, McGowan J, Ockene JK, O’Sullivan MJ, Phillips L, Prentice RL, Sarto GE, Stefanick ML, Van Horn L, Wactawski-Wende J, Whitlock E, Anderson GL, Assaf AR, Barad D. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:669–683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lips P, Graafmans WC, Ooms ME, Bezemer PD, Bouter LM. Vitamin D supplementation and fracture incidence in elderly persons. A randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:400–406. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-4-199602150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, Cauley JA, Thompson DE, Nevitt MC, Bauer DC, Genant HK, Haskell WL, Marcus R, Ott SM, Torner JC, Quandt SA, Reiss TF, Ensrud KE. Fracture intervention trial research group: randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Lancet. 1996;348:1535–1541. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delmas PD, Recker RR, Chesnut CH, III, Skag A, Stakkestad JA, Emkey R, Glibride J, Schimmer RC, Christiansen C. Daily and intermittent oral ibandronate normalize bone turnover and provide significant reduction in vertebral fracture risk: results from the BONE study. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:792–798. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nieves JW, Komar L, Cosman F, Lindsay R. Calcium potentiates the effect of estrogen and calcitonin on bone mass: review and analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:18–24. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/67.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanvetyanon T, Stiff PJ. Management of the adverse effects associated with intravenous bisphosphonates. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:897–907. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lekkerkerker F, Kanis JA, Alsayed N, Bouvenot G, Burlet N, Cahall D, Chines A, Delmas P, Dreiser RL, Ethgen D, Hughes N, Kaufman JM, Korte S, Kreutz G, Laslop A, Mitlak B, Rabenda V, Rizzoli R, Santora A, Schimmer R, Tsouderos Y, Reginster JY. Adherence to treatment of osteoporosis: a need for a study. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1311–1317. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0410-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Compston JE, Seeman E. Compliance with osteoporosis therapy is the weakest link. Lancet. 2006;368:973–974. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69394-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cortet B, Benichou O. Adherence, persistence, concordance: do we provide optimal management to our patients with osteoporosis? Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73:e1–e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCombs JS, Thiebaud P, Laughlin-Miley C, Shi J. Compliance with drug therapies for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis. Maturitas. 2004;48:271–287. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossini M, Bianchi G, Di MO, Giannini S, Minisola S, Sinigaglia L, Adami S. Determinants of adherence to osteoporosis treatment in clinical practice. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:914–921. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0073-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siris ES, Selby PL, Saag KG, Borgström F, Herings RMC, Silverman SL. Impact of osteoporosis treatment adherence on fracture rates in North America and Europe. Am J Med. 2009;122:S3–S13. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van den Boogaard CH, Breekveldt-Postma NS, Borggreve SE, Goettsch WG, Herings RM. Persistent bisphosphonate use and the risk of osteoporotic fractures in clinical practice: a database analysis study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1757–1764. doi: 10.1185/030079906X132370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nikolaus T, Kruse W, Bach M, Specht-Leible N, Oster P, Schlierf G. Elderly patients' problems with medication. An in-hospital and follow-up study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1996;49:255–259. doi: 10.1007/BF00226324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rees TP, Howe I. A randomised, single-blind, crossover comparison of the acceptability of the calcium and vitamin D3 supplements Calcichew D3 Forte and Ad Cal D3 in elderly patients. Curr Med Res Opin. 2001;16:245–251. doi: 10.1185/030079901750120178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reginster YR, Kaufman JM, Gangjii V. Preference for and acceptability of two formulations of a dietary containing calcium plus vitamin D3: a randomised, open-label, crossover trial in adult patients with calcium and vitamin D deficiencies. Curr Therap Res. 2005;66:23–34. doi: 10.1016/j.curtheres.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dawson-Hughes B, Harris SS, Krall EA, Dallal GE. Effect of withdrawal of calcium and vitamin D supplements on bone mass in elderly men and women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:745–750. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.3.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grant AM, Avenell A, Campbell MK, Cooper C, Donaldson C, Francis RM, Gillespie WJ, Robinson CM, Torgerson DJ, Wallace WA, McPherson GC, MacLennan GS, McDonald AM. Oral Vitamin D3 and calcium for secondary prevention of low-trauma fractures in elderly people (Randomised Evaluation of Calcium Or vitamin D, RECORD): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1621–1628. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)63013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salzman C. Medication compliance in the elderly. J Clin Psychiatry. 1995;56(Suppl 1):18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keen R, Jodar E, Iolascon G, Kruse HP, Varbanov A, Mann B, Gold DT. European women's preference for osteoporosis treatment: influence of clinical effectiveness and dosing frequency. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:2375–2381. doi: 10.1185/030079906X154079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tosteson AN, Grove MR, Hammond CS, Moncur MM, Ray GT, Hebert GM, Pressman AR, Ettinger B. Early discontinuation of treatment for osteoporosis. Am J Med. 2003;115:209–216. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00362-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zafran N, Liss Z, Peled R, Sherf M, Reuveni H. Incidence and causes for failure of treatment of women with proven osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1375–1383. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1838-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reginster JY, Rabenda V, Neuprez A. Adherence, patient preference and dosing frequency: understanding the relationship. Bone. 2006;38(4 Suppl 1):S2–S6. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.01.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]