Abstract

Three hypotheses are evaluated in this study. The first predicts that feelings of gratitude will offset (i.e., moderate) the deleterious effects of chronic financial strain on depressive symptoms over time. The second hypothesis specifies that people who go to church more often will be more likely to feel grateful. The third hypothesis predicts that individuals with a strong sense of God-mediated control will also feel more grateful. Data from a nationwide longitudinal study of older adults in the United States (N = 818) provide support for all three hypotheses. The data suggest that the effects of ongoing economic difficulty on depressive symptoms are especially pronounced for older people who are less grateful. But in contrast, persistent financial difficulties fail to exert a statistically significant effect on depressive symptoms over time for older individuals who are especially grateful. The results further reveal that more frequent church attendance and stronger God-mediated control beliefs are associated with positive changes in gratitude over time.

Keywords: Gratitude, financial strain, depression, religion

The purpose of this study is to see if feelings of gratitude offset the deleterious effect of chronic financial strain on depressive symptoms in late life. In the process, an effort is made to determine if feelings of gratitude are influenced by greater involvement in religion. Studying gratitude is challenging because, as Emmons, McCullough, and Tsang (2003, p. 327) pointed out, gratitude is difficult to define, and it, “…defies easy classification. It has been conceptualized as an emotion, an attitude, a moral virtue, a habit, a personality trait, and a coping response.” No attempt will be made to resolve these long-standing issues here. Instead, for the purposes of the current study, gratitude is viewed as a virtue or character strength that involves feelings of thankfulness that arise, “… in response to receiving a gift, whether the gift be a tangible benefit from a specific other or a moment of peaceful bliss evoked by natural beauty” (Peterson & Seligman, 2004, p.554).

The theoretical rationale for this study is developed below in two sections. First, the roots of gratitude are examined, with an emphasis on the potentially important influence of religion. Following this, the way in which gratitude may buffer or offset the deleterious effects of stress on depressive symptoms is explored in detail.

Religious Influences on Gratitude

So far, most researchers have been concerned with the way gratitude may influence a range of outcomes, including physical health status and psychological well-being (e.g., Watkins, 2004). In contrast, fewer studies have explored the factors that promote stronger feelings of in the first place. Simply put, relatively few investigators have treated gratitude as a dependent variable in their work. This is especially true with respect to studies involving the influence of religion on gratitude. This is surprising because, as Peterson and Seligman (2004) report, the virtue of gratitude is highly prized by the Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and Hindu faith traditions. Empirical support for the notion that gratitude is influenced by involvement in religion may be found, for example, in a study by Emmons and Kneezel (2005). Their work revealed that people who go to church more often and read the Bible more frequently tend to experience more grateful emotions than individuals who are less involved in these facets of religion. In the process of reviewing this research, it is important to point out that religiously-motivated feelings of gratitude are not necessarily restricted to God alone. Instead, as Roberts (2004) maintained, religiously-motivated feelings of gratitude may extend to other people, as well.

Because research on religion and gratitude is underdeveloped, a major goal of the current study is to examine whether religion influences feelings of gratitude. Although religion may influence feelings of gratitude in a number of ways, the discussion that follows begins with a facet of religion that has not been considered so far - God-mediated control beliefs. God-mediated control is defined as the belief that God works together with people to help them overcome the difficulties and challenges that arise in their lives (Krause, 2005). It should be emphasized, however, that God-mediated control may also be manifest in situations that do not involve adversity. For example, an individual may rely on God to help them attain positive goals, as well.

Instead of merely showing that God-mediated control enhances feelings of gratitude, the discussion that follows also aims to explore the factors that influence this important religious resource. This will be accomplished below by arguing that God-mediated control beliefs arise and are maintained by participation in religious services. By linking two distinct aspects of religion with gratitude, the intent is to sketch out a more well-developed theoretical rationale for the religious underpinnings of gratitude. Following this, the potentially unique aspects of religiously motivated gratitude are examined briefly.

God-Mediated Control and Gratitude

Researchers have argued for some time that one of the primary goals of religion is to provide people with the sense that it is possible to control the events that happen in their lives (Spilka, Hood, Hunsberger, & Gorsuch, 2003). A central premise in the current study is that this is accomplished, in part, by instilling the belief that God stands ready to help when difficulties and challenges arise and when people strive to attain positive goals. If religion helps people meet their basic need for control, then it is not difficult to see why they might feel grateful when this benefit has been received.

Attendance at Worship Services and God-Mediated Control

There are likely to be a number of ways in which greater involvement in religion may foster a deeper sense of God-mediated control. However, one essential facet of religion that may play a role in this process is participation in religious rituals, especially worship services. This view is consistent with the work of Stark and Finke (2000), who argued that an individual's confidence in religious teachings is strengthened through participation in religious rituals. The sermons, hymns, and group prayers that are integral parts of many worship services encourage worshipers to believe that God will help them exercise greater control in their lives.

Two potentially important hypotheses arise from bringing attendance at worship services to the foreground. First, study participants who attend worship services more often will have stronger God-mediated control beliefs than study participants who do not go to worships services as often. Second, people with a greater sense of God-mediated control will feel more grateful than individuals who do not feel that God helps them control the things that happen in their lives. Viewed in more technical terms, these hypotheses specify that participation in worship services affects feelings of gratitude indirectly by promoting stronger feelings of God-mediated control. This perspective is consistent with the views of Emmons (2005), who argued that religious emotions, such as gratitude, arise from and are elicited through religious practices.

Unique Aspects of Religiously Motivated Feelings of Gratitude

There are three closely-related ways in which religiously motivated feelings of gratitude may differ from feelings of gratitude that arise elsewhere. First, by fostering a sense of gratitude, religious institutions provide a way for worshipers to express their faith and communicate their religious convictions to others (Emmons, 2005). Second, as noted above, every major faith tradition in the world encourages people to feel grateful. Consequently, individuals who practice these teachings are likely to feel a deeper sense of satisfaction and fulfillment in their faith. Third, if fellow worshipers also feel grateful, then this shared sense of gratitude may help promote more positive in-group feelings and foster greater congregational solidarity.

Exploring the Stress-Buffering Effects of Gratitude

Although research on gratitude is still in its infancy (Peterson & Seligman, 2004), researchers are beginning to link a greater sense of gratitude with a wide range of constructs, including more frequent exercise (Emmons & McCullough, 2003), higher levels of enthusiasm and determination (Emmons, McCullough, & Tsang, 2003), and a greater likelihood of helping others (McCullough, Emmons, & Tsang, 2002). However, a small clusters of findings is especially important for the current study. This research suggests that people who are more grateful tend to have more positive emotions (Sheldon, 2006) and fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety (McCullough et al., 2002).

Researchers have identified a number of mechanisms that may explain the relationship between gratitude and psychological well-being (Watkins, 2004), but the potential stress-buffering properties of gratitude are especially intriguing. There at least two ways in which feelings of gratitude may offset the pernicious effects of stress: one involves religion directly while the other is broader and encompasses secular influences.

The religious explanation may be found in the work of Krause (2006). He argued that one of the core messages of the Christian faith involves trusting that God has a purpose and plan for each person's life, and even though this plan involves exposure to difficult experiences and adversities, the goal is to promote greater spiritual and personal development (Koenig, 1994). If people believe that the problems they face are part of God's plan to strengthen them and help them grow, then they are more likely to feel grateful to God when adversity arises. Having linked adversity with gratitude, Krause (2006) went on to suggest one way in which gratitude may, in turn, buffer the noxious effects of stress. When people are confronted with adverse situations, they often experience a flood of negative emotions. These negative feelings are captured succinctly by Pearlin and his colleagues in their discussion of the deleterious effects of persistent financial strain (Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman, & Mullin, 1981). These investigators maintained that, “… persistent role strains can confront people with dogged evidence of their own failures - or lack of success - and with inescapable proof of their inability to alter the unwanted circumstances in their lives” (Pearlin et al., 1981, p. 340). One way in which gratitude may buffer the effects of stress is by counterbalancing these negative emotions with positive feelings. And as Emmons and McCullough (2003) pointed out, gratitude may serve this important function because people who are grateful tend to experience a greater sense of contentment, happiness, pride, and hope. As noted above, the focal stressor in the current study is chronic financial strain. This is an important stressor to examine because an extensive number of studies reveal that people who are exposed to ongoing financial difficulties are more likely to experience symptoms of depression than individuals who are not confronted by persistent economic challenges (e.g., Mendes de Leon, Rapp, & Kasl, 1994). Perhaps the positive emotions that are fostered by religiously-based feelings of gratitude provide a powerful antidote to the feelings of depression that often accompany ongoing financial problems.

Evidence of the offsetting function that is performed by positive emotions may be found in the work of Fredrickson, Mancuso, Branigan, and Tugade (2000). According to their “undoing hypothesis”, positive emotions help people correct or overcome negative emotions by broadening their thought-action repertoires, thereby encouraging them to pursue a wider range of thoughts and actions than they typically consider when they are struggling with negative emotions. Having a broader thought-action repertoire is important because it can lead to more effective coping responses.

The second mechanism that may explain the potentially important stress-buffering effects of gratitude may be found by extending theoretical insights in the literature on chronic strain. By definition, chronic difficulties, such as financial strain, are persistent and ongoing. As a result, there is often little that people can do to eliminate or avoid them. This is especially true with respect to chronic economic problems that arise in late life. Many older people live on fixed incomes and they often have relatively few opportunities for improving their financial situation, such as re-entering the labor force. Under these circumstances, some researchers maintain that people try to cope with chronic stressors by investing their energies and efforts in other areas in their lives where they can exercise more control and where they can find greater satisfaction and meaning (Gottlieb, 1997). More specifically, Gottlieb (1997) argued that, “‥valued activities that seem to be unrelated to the primary difficulties of life, especially activities that are self-initiated, may in fact serve the indirect function of augmenting a sense of control, placing those difficulties in a broader perspective, and offsetting the distress occasioned by them with positive experiences and emotional states” (p. 31). To the extent that this type of compensatory coping strategy is successful, people are likely to feel grateful when they are able to find positive experiences in the face of adversity.

Two studies provide empirical support for the theoretical rationale that is developed in this section. The first, by Krause (2006), revealed that the deleterious effects of stressful life events on self-rated health are offset for older people with greater feelings of gratitude toward God. Although this study makes a contribution to the literature, it suffers from at least two limitations. First, the data are cross-sectional. As a result, strong assumptions must be made about the direction of causality between key study constructs, such as gratitude and health. Second, as the literature on stress has evolved, researchers quickly became aware that there are a number of different kinds of stressors, including stressful life events, daily hassles, and chronic strain (see Cohen, Kessler, & Underwood Gordon, 1995, for a detailed discussion of these different stressors). And perhaps more important, some investigators maintain that some kinds of stressors have a greater effect on physical and mental health than other types of stressful experiences. More specifically, as Lepore (1995) argued, stressors that are persistent and ongoing (i.e., chronic strain) are more likely to exert an adverse effect on physical and mental health than either stressful life events or daily hassles. If chronic strain exerts a more deleterious effect than other stressors, then one way to assess the full potential of coping resources like gratitude is to see if it helps people deal more effectively with these especially difficult challenges.

The second study to assess the potential stress-buffering effects of gratitude was conducted by Wood, Joseph, and Linley (2007). These investigators examined the interface among gratitude, stress, coping responses, and psychological well-being. The findings from this study suggest that people with a greater sense of gratitude are more likely to ask for social support from significant others, find growth in the face of adversity, and engage in positive coping responses, such as active problem solving. This study further reveals that greater feelings of gratitude are associated with greater life satisfaction, greater happiness, and fewer symptoms of depression. However, it was surprising to see that these coping responses do not explain the relationship between gratitude and these psychological well-being outcome measures. However, the findings from this study further reveal that coping appeared to mediate the relationship between gratitude and stress.

Although the study by Wood et al. (2007) makes a number of valuable contributions to the literature, there are at least three limitations in the work that was done by these investigators. First, the data are cross-sectional. Second, the sample is comprised of college students. This makes it difficult to determine if the results can be generalized to people in other age groups as well as the wider population as a whole. Third, Wood et al. (2007) relied on the widely used measure of perceived stress that was devised by Cohen and Williamson (1988). This scale consists of ten items that ask study participants whether they feel their lives are unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overwhelming. Unfortunately, there are problems with this measure of stress. For decades, many researchers have argued that stress refers to external events, such as the death of a loved one or economic difficulty (e.g., Thoits, 1983). In contrast, emotions such as feeling overwhelmed represent the outcome of stress - these emotions are what stress creates or what stress does but they do not capture what stress is. As a result, a number of investigators have argued that responses to perceived stress items are confounded with the mental health outcomes they are supposed to predict (e.g., Monroe & Kelley, 1995).

The current study was designed to confront four key limitations in work on religion, gratitude, stress, and well-being. First, the analyses presented below are based on data from a national probability sample of older adults who were interviewed at more than one point in time. This makes it possible to assess the effects of financial strain and gratitude on change in depressive symptoms over time as well as the effects of religion on change in gratitude over time. Second, this study aims to expand the scope of research on gratitude, stress, and well-being by focusing on a type of stressor (i.e., chronic strain) that does not appear to have been evaluated empirically in other studies on gratitude. Third, the widely accepted measure of stress that is used in the current study is anchored in clearly defined external circumstances (i.e., chronic financial strain) and therefore it is less likely to be confounded with the outcome it is used to predict. Fourth, by focusing God-mediated control beliefs, this study brings a dimension of religion to the foreground that has not been examined previously in research on gratitude.

Methods

Sample

The data for this study come from a nationwide longitudinal survey of older adults. Altogether, six waves of interviews have been conducted. The study population was defined as all household residents who were noninstitutionalized, English-speaking, 65 years of age or older, and retired (i.e., not working for pay). In addition, residents of Alaska and Hawaii were excluded from the study population.

Three waves of interviews were conducted between 1992 and 1999: Wave 1 (N = 1,103); Wave 2 (N = 605), Wave 3 (N = 530). In 2002-2003, a fourth wave of interviews was conducted. However, the sampling strategy for the Wave 4 survey was complex. Two groups of older people were interviewed at this time. All survivors from Waves 1-3 were interviewed first (N = 269). This group was then supplemented with a sample of new study participants who had not been interviewed previously (total Wave 4 N = 1,518) (see Krause, 2004 for a detailed discussion of this sampling strategy). Following this, a fifth wave of interviews was completed in 2005 (N = 1,166) and a sixth wave of interviews in 2007 (N = 1,011).

The data used in the current study are from the Wave 5 and Wave 6 surveys. These data points were selected because questions on gratitude and religion were administered for the first time in the Wave 5 interviews. After using listwise deletion of cases to deal with item nonresponse, the sample sizes in the analyses presented below range from 818 to 839 cases. Based on the sample comprising 818 individuals, preliminary data analysis revealed that the average age of the study participants at the Wave 5 interview was 76.0 years (SD = 6.6 years), 40% were older men, 58.6% were married at Wave 5, and the study participants reported completing an average of 12.2 years of schooling (SD = 3.3 years). Finally, 90% of the study participants were white, 7 % were African American, and 3% were members of other racial groups. These descriptive data, as well as the data in the analyses that follow have been weighted.1

Measures

Table 1 contains the core measures that are used in this study. The procedures used to code these indicators are provided in the footnotes of this table.

Table 1.

Core Study Measures

|

These items were scored in the following manner (coding in parenthesis): rarely or none of the time (1); some or a little of the time (2); occasionally or a moderate amount of the time (3); most or all of the time (4).

These items were scored in the following manner: disagree strongly (1); disagree (2); agree (3); agree strongly (4).

This item was scored in the following manner: none (1); only a little (2); some (3); a great deal (4).

This item was scored in the following manner: money left over (1); just enough (2); not enough to make ends meet (3).

This item was scored by asking study participants to rank their financial situation on a scale from 0 to 10, where a score of 0 means the best possible financial situation and a score of 10 means the worst possible financial situation.

This item was scored in the following manner: never (1); less than once a year (2); about once or twice a year (3); several times a year (4); about once a month (5); 2-3 times a month (6); nearly every week (7); every week (8); several times a week (9).

This item was scored in the following manner: never (1); less than once a month (2); once a month (3); a few times a month (4); once a week (5); a few times a week (6); once a day (7); several times a day (8).

Depressive Symptoms

Four items were taken from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) to assess depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977). These indicators reflect the cognitive-affective aspects of depressive symptoms, including feeling sad, blue, and depressed. Identical depressed affect measures were administered in the Wave 5 and Wave 6 surveys. A high score on this brief scale denotes greater depressive symptomatology. The internal consistency reliability estimates for the depressed affect at Wave 5 (.853) and Wave 6 (.879) are good. The mean depressed affect score at the Wave 5 survey was 5.141 (SD = 2.072) and the mean at Wave 6 was 5.227 (SD = 2.255).

Gratitude

Gratitude is assessed in the Wave 5 and Wave 6 surveys with three items. The first two indicators come from the work of McCullough et al. (2002). The third item was taken from the measure of gratitude that was devised by Peterson and Seligman (2004). A high score on these indicators represents a greater sense of gratitude. The internal consistency reliability estimate at Wave 5 is .822 and the corresponding estimate at Wave 6 is .832. The mean of the gratitude scale at Wave 5 is 10.955 (SD = 1.399) and the mean at Wave 6 is 11.052 (SD = 1.432).

Chronic Financial Strain

Chronic financial strain was measured at the Wave 5 survey with three items that were devised by Pearlin and his colleagues (Pearlin et al., 1981). A high score on these indicators denotes greater financial difficulty. The reliability estimate at Wave 5 is .797. The mean financial strain score is 6.026 (SD = 3.157).3

Frequency of Church Attendance

Three measures of religion are included in this study. The first assesses how often study participants attend religious services. A high score denotes more frequent church attendance at Wave 5. The mean at Wave 5 is 5.865 (SD = 2.888).

The Frequency of Private Prayer

The second measure of religion assesses how often older people pray when they are alone. A high score reflects more frequent prayer. The mean at Wave 5 is 6.539 (SD = 1.875).

God-Mediated Control

Two items were included in this study to measure feelings of God-mediated control. These items were taken from the work of Krause (2005). The correlation between these two indicators at Wave 5 is .866 and the mean is 6.854 (SD = 1.424).

Demographic Control Variables

The relationships among financial strain, religion, gratitude, and depressive symptoms are evaluated after the effects of age, sex, education, and marital status are controlled statistically. The demographic control measures were all taken from the Wave 5 survey. Age is scored continuously in years and education reflects the total number of years of schooling that were completed successfully by study participants. In contrast, sex (1 = men; 0 = women) and marital status (1 = married; 0 = otherwise) are measured in a binary format.

Results

The findings from this study are presented below in two sections. The first section contains the results from the analyses that were designed to see if feelings of gratitude offset the pernicious effect of chronic financial strain on change in depressive symptoms over time. The findings from the analyses that assess the relationship between religious involvement and feelings of gratitude over time are provided in section two.

Gratitude, Financial Strain, and Change in Depressive Symptoms

Table 2 contains the results from the analyses that were designed to see if feelings of gratitude offset the deleterious effects of chronic financial strain on change in depressive symptoms over time. If this study hypothesis is valid, then the noxious effects of financial strain on depressive symptoms should become progressively weaker at successively higher levels of gratitude. Stated in more technical terms, this hypothesis predicts that there will be a statistical interaction effect between financial strain and gratitude on change in depressive symptoms. Tests for this interaction were performed with a hierarchical ordinary least squares multiple regression analysis consisting of two steps. In the first step (see Model 1 in Table 2), measures of financial strain, gratitude, baseline depression, and the other independent variables were entered into the equation. Then, a multiplicative term was added in the second step (Model 2). This cross-product term was created by multiplying financial strain scores by scores on the gratitude measure. This multiplicative term is used to test for the proposed interaction effect. All independent variables were centered on their means prior to estimating the Models 1 and 2. In addition, the multiplicative term was formed by multiplying the centered values of gratitude and financial strain.

Table 2.

Financial Strain, Gratitude, and Change in Depressive Symptoms From Wave 5 to Wave 6 (N = 818)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | ||

| Age | .067*a | .071* |

| (.023)b | (.025) | |

| Sex | -.108** | -.015** |

| (-.498) | (-.481) | |

| Education | -.047 | -.045 |

| (-.033) | (-.031) | |

| Marital Status | .036 | .035 |

| (.164) | (.159) | |

| Church Attendance | -.112** | -.107** |

| (-.088) | (-.084) | |

| Prayer | .070 | .070 |

| (.084) | (.084) | |

| Financial Strain | .081* | .076* |

| (.056) | (.054) | |

| Gratitude | -.016 | -.003 |

| (-.026) | (-.005) | |

| (Financial Strain × Gratitude) | --- | --- |

| --- | (-.059)*** | |

| Depressive Symptoms Wave 5 | .292*** | .289*** |

| (.318) | (.314) | |

| Multiple R2 | .166 | .179 |

standardized regression coefficient

metric (unstandardize) coefficient

= p < .05;

= p < .01;

= p < .001

The data in the left-hand column of Table 2 initially appear to suggest that financial strain exerts only a modest effect on depressive symptoms over time (Beta = .081; p < .05). Moreover, the results seem to indicate that feelings of gratitude do not have a statistically significant effect on change in depressive symptoms (Beta = -.016; n.s.). Based on these findings alone, it might be tempting to conclude that depressive symptoms are not substantially affected by either persistent financial difficulties or feelings of gratitude. However, the data in the right-hand column of Table 2 (see Model 2) provide a different view.

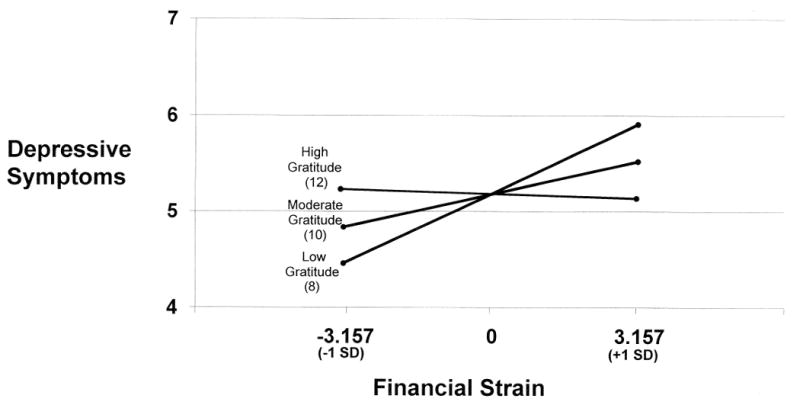

The findings derived from estimating Model 2 reveal that there is a statistically significant interaction effect between financial strain and feelings of gratitude on change in depressive symptoms over time (b = -.059; p < .001; unstandardized coefficients are presented when interaction effects are reviewed because standardized estimates are not meaningful when the cross-product term has been created from centered variables). Even though the data suggest that there is a statistically significant interaction effect in the data, it is somewhat difficult to determine if it is in the predicted direction. Fortunately, two steps can be taken to clarify the study findings. First, formulas provided by Aiken and West (1991) can be used to estimate the effects of financial strain on change in depressive symptoms at select levels of gratitude. Although any level of gratitude may be used to illustrate the observed interaction effect, the following raw score values on the gratitude scale were selected for this purpose: 8, 10, and 12.4

The additional calculations indicate that the pernicious effect of chronic financial strain on change in depressive symptoms are fairly pronounced for older people with relatively lower levels of gratitude (i.e., a score of 8) (Beta = .320; b = .228; p < .001). However, the findings further reveal that the size of the effect of ongoing financial difficulty on change in depression is reduced by about 50% for older people with greater feelings of gratitude (i.e., a score of 10) (Beta = .155; b = .110; p < .001). Finally, the results suggest that financial strain fails to exert a statistically significant influence on change in depressive symptoms for older people with the highest observed gratitude scores (i.e., a score of 12) (Beta = -.011; n.s.).5

Aiken and West (1991) provide a second way to illustrate the nature of statistical interaction effects. This involves plotting the relationship between financial strain and change in depressive symptoms at select values of gratitude. This plot, which appears in Figure 1, was obtained with values of 8, 10, and 12 on the gratitude scale

Figure 1.

The Statistical Interaction Effect Between Gratitude and Financial Strain on Change in Depressive Symptoms

Religious Involvement and Change in Gratitude

The data provided up to this point indicate that gratitude may help offset the deleterious effects of financial strain on change in depressive symptoms over time. However, because people may feel grateful for many reasons, it is important to see if religion plays a significant role in shaping feelings of gratitude. As discussed above, this is accomplished by assessing whether attendance at worship services affects change in feelings of gratitude indirectly by bolstering God-mediated control beliefs. Following the recommendations of Baron and Kenny (1986), this mediating effect is evaluated by estimating three equations that focus on: (1) the relationship between the frequency of church attendance and gratitude, (2) the relationship between church attendance, God-mediated control, and gratitude, and (3) the relationship between attendance at worship services and God-mediated control beliefs. The results from these analyses are presented in Tables 3 through 5.

Table 3.

Church Attendance and Change in Gratitude From Wave 5 to Wave 6 (N = 839)

| Independent Variables | |

| Age | -.006a |

| (-.001)b | |

| Sex | -.010 |

| (-.029) | |

| Education | .028 |

| (.013) | |

| Marital Status | .030 |

| (.089) | |

| Church Attendance | .193*** |

| (.097) | |

| Gratitude Wave 5 | .277*** |

| (.294) | |

| Multiple R2 | .158 |

standardized regression coefficient

metric (unstandardized) regression coefficient

= p < .05;

= p < .01;

= p < .001

Table 5.

Church Attendance and God-Mediated Control Wave 5 Only (N = 839)

| Independent Variables | |

| Age | .015a |

| (.003)b | |

| Sex | -.086** |

| (-.249) | |

| Education | -.090** |

| (-.040) | |

| Marital Status | -.005 |

| (-.015) | |

| Church Attendance | .520*** |

| (.256) | |

| Multiple R2 | .285 |

standardized regression coefficient

metric (unstandardized) regression coefficient

= p < .01;

= p < .001

The data in Table 3 indicate that more frequent attendance at worship services at Wave 5 is associated with positive changes in gratitude at Wave 6 (Beta = .193; p < .001).6 Moreover, the findings in Table 4 suggest that older adults with strong God-mediated control beliefs tend to report stronger feelings of gratitude over time than older people with weaker God-mediated control beliefs (Beta = .107; p < .01). However, once God-mediated control beliefs were entered into the model containing church attendance, the relationship between church attendance and change in gratitude declines (Beta = .149; p < .001; see Table 4). Put another way, the findings in Tables 3 and 4 indicate that God-mediated control beliefs explain about 23% of the effect of the frequency of church attendance on change in feelings of gratitude over time.7 As Baron and Kenny (1986) point out, one last step is required in order to properly illustrate the hypothesized mediating effect. More specifically, it is necessary to show that the frequency of church attendance is associated with God-mediated control beliefs. The findings from the analysis that was designed to examine this issue are presented in Table 5. As these data show, older people who go to church more often tend to have substantially stronger God-mediated control beliefs than older adults who do not go to church as often (Beta = .520; p < .001).

Table 4.

Church Attendance, God-Mediated Control and Change in Gratitude From Wave 5 to Wave 6 (N = 839)

| Independent Variables | |

| Age | -.006a |

| (-.001)b | |

| Sex | -.002 |

| (-.007) | |

| Education | .038 |

| (.017) | |

| Marital Status | .032 |

| (.095) | |

| Church Attendance | .149*** |

| (.075) | |

| God-Mediated Control | .107** |

| (.110) | |

| Gratitude Wave 5 | .236*** |

| (.251) | |

| Multiple R2 | .158 |

standardized regression coefficient

metric (unstandardized) regression coefficient

= p < .01;

= p < .001

Conclusions

The results from the current study add to the mounting evidence which suggests that feelings of gratitude may help people deal more effectively with the pernicious effects of stress (Krause, 2006; Wood et al., 2007). Two key findings emerged from this research. First, the data suggest that chronic financial strain has a fairly substantial impact on depressive symptoms for older adults who are relatively less grateful. But in contrast, the findings further reveal that the noxious effects of persistent economic problems on depressive symptoms are completely offset for older people who are the most grateful. These results are noteworthy because this appears to be the first time that the relationships among chronic financial strain, gratitude, and depressive symptoms have been evaluated with data that have been gathered at more than one point in time.

The second major finding in this study involves the potentially important role that religion may play in shaping feelings of gratitude in late life. The data indicate that older people who attend worship services more often are likely to feel more grateful over time than older adults who do not go to church as often. Moreover, the findings reveal that at least part of the effect of church attendance on gratitude may be attributed to the intervening influence of God-mediated control beliefs. Put another way, these results suggest that people who go to church more often tend to have stronger God-mediated control beliefs and people with stronger God-mediated control beliefs, in turn, tend to feel more grateful. These findings are noteworthy because this appears to be the first time that the relationship between God-mediated control beliefs and gratitude has been evaluated in the literature.

Although the findings from the current study may have contributed to the literature, a good deal of work remains to be done. For example, researchers need to probe more deeply into the potentially important stress-buffering properties of gratitude. Earlier, it was proposed that people who are more grateful tend to rely on specific types of coping responses to deal with the effects of ongoing financial strain, such as finding meaning and satisfaction in other domains of life. However, these intervening coping responses were not examined empirically in the current study because measures of them were not included in the survey. Exploring the interface between chronic strain, gratitude, and a full range of coping responses should be a high priority in the future.

One contribution of the current study arises from the fact that an emphasis was placed on evaluating a type of stressful experience that has not been assessed by other investigators (i.e., chronic strain). Researches can continue to advance studies in this area by seeing whether feelings of gratitude help people cope more effectively with the effects of other kinds of stressors, especially traumatic events. Traumatic events are defined as stressors that are, “…spectacular, horrifying, and just deeply disturbing experiences” (Wheaton, 1994, p.90). Traumatic events are distinguished from other types of stressors by their imputed seriousness. Included among traumatic events are sexual and physical abuse, witnessing a violent crime, and participation in combat. Recall that chronic strain is assumed to be more detrimental than stressful events. Yet gratitude appears to buffer the effects of chronic strain. Since traumatic events are presumed to be even more noxious than either chronic strain or stressful events, researchers need to see if gratitude is effective even under such especially trying circumstances, as well. In this way, it will be possible to determine if there are limits in the stress-buffering properties of gratitude, or whether the beneficial effects of this character strength are evident in all types of stressful experiences.

Although the findings from the current study suggest that God-mediated control beliefs and the frequency of attendance at worship services may influence feelings of gratitude, more research is needed to see if other dimensions of religion may be involved in this process, as well. For example, more work is needed to see if the exchange of social support in congregations tends to enhance feelings of gratitude among fellow church members (see Krause, 2008, for a discussion of this issue).

In the process of exploring these as well as other issues, researchers would be well advised to keep the limitations of the current study in mind. Three are especially important. First, even though the data from the current study were obtained at more than one point in time, it is still not possible to claim that gratitude definitely “causes” a decline in depression. Such assertions can be made only with studies that utilize a true experimental design. Even so, a recent study by Wood and his associates reveals that gratitude is associated with lower levels of depression over time, but depression did not significantly influence feelings of gratitude over time (Wood et al., 2008). Second, the major outcome variable in the current study was depressive symptoms. Because data were not available on the clinical psychiatric syndromes that are assessed in DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), the extent to which gratitude influences the kind of mental health problems that are encountered by mental health professionals cannot be determined conclusively. Third, researchers have argued for some time that response bias (especially social desirability) may adversely influence the way people answer questions about religion (e.g., Batson, Schoenrade, & Ventis, 1993). Measures of response bias were not available in the current study. Consequently, it may be important for investigators to control for response bias in future research.8

Although there are limitations in the current study, the findings point to some exciting possibilities for improving the well-being of older people. For example, Emmons and McCullough (2003) devised a series of experiments which show that it is possible to manipulate feelings of gratitude in order to subsequently enhance a person's sense of psychological well-being. If involvement in religion is associated with greater feelings of gratitude, then perhaps ways can be found in the church to deliberately bolster feelings of gratitude among older adults. For example, Bible study or prayer groups may be structured so that they help older people identify, express, and discuss reasons for why they should feel grateful.

Down through the ages, scholars, sages, and philosophers have extolled the virtues of feeling grateful. One noted proponent of gratitude was Marcus Aurelius, an emperor of ancient Rome, who lived in the second century A.D. He was one of the most famous Stoic philosophers. Issues involving gratitude are evident in his recommendation on how to live life: “Pass then through this little space of time conformably to nature, and end the journey in content, just as an olive falls off when it is ripe, blessing nature who produced it, and thanking the tree on which it grew” (as quoted in Eliot 1909, p. 222). The emphasis on end of life issues in these insights speaks directly to the central role that is played by feelings of gratitude in late life. Although a number of the early philosophers wrote about gratitude, they discussed the benefits of feeling grateful in a very general way, linking it only loosely with broad quality of life issues. Work in the current century is set off from these intellectual roots by empirically linking gratitude with public health problems, such as physical and mental health, and developing conceptual models that spell out how the presumed health-related benefits of gratitude arise. But our conceptual approaches are still quite crude and there is room for considerable improvement in the research that has been done. When viewed at the broadest level, the greatest contribution of the current study may lie less in what has been empirically demonstrated and more in the insights and enthusiasm it sparks in the minds of those who wish to pursue issues that have been pondered for centuries.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the grants from the National Institute on Aging (RO1 AG014749; RO1 AG009221; Principal Investigator - Neal Krause) and a grant from the Templeton Foundation through the Duke University Center for Spirituality, Theology, and Health.

Notes

A preliminary test was conducted to see if the loss of subjects over time occurred non-randomly. This was accomplished by seeing whether select data at the Wave 5 survey are associated with study participation status at the Wave 6 interview. The following procedures were used to address this issue. First, a nominal-level variable containing three categories was created to represent older adults who participated in both the Wave 5 and Wave 6 surveys (scored 1), older people were alive but did not participate at Wave 6 but were presumed to be alive (scored 2), and older individuals who died during the interval between the Wave 5 and Wave 6 interviews (scored 3). Then, using multinomial logistic regression, this categorical outcome was regressed on the Wave 5 measures of age, sex, education, marital status, the frequency of church attendance, the frequency of private prayer, financial strain, gratitude, and depressive symptoms. The category representing older people who remained in the study served as the reference group in this analysis.

The results reveal that there are no statistically significant differences in the relationships between any of the Wave 5 study measures and study participation status for older adults who took part in both the Wave 5 and Wave 6 surveys and older people who dropped out of the study but were presumed to be alive (age odds ratio = 1.016, n.s.; sex odds ratio = 1.330, n.s.; marital status odds ratio = .819; n.s.; education odds ratio = .997; n.s.; the frequency of church attendance odds ratio = .961; n.s.; the frequency of private prayer odds ratio = .982; n.s.; financial strain odds ratio = 1.014; n.s.; gratitude odds ratio = 1.009; n.s.; depressive symptoms odds ratio = 1.072; n.s.).

In contrast, the data suggest that compared to older people who remained in the study, those who died were older (odds ratio = 1.094; p < .001) and they were more likely to be men (odds ratio = 2.299; p < .001). However, statistically significant differences failed to emerge with respect to the Wave 5 measures of marital status (odds ratio = .599; n.s.), education (odds ratio = .975; n.s.), the frequency of church attendance (odds ratio = .949; n.s.), the frequency of private prayer (odds ratio = 1.193; n.s.), financial strain (odds ratio = .969; n.s.), gratitude (odds ratio = 1.007; n.s.), and depressive symptoms (odds ratio = 1.085; n.s.).

There is considerable disagreement in the literature over the effects of non-random sample attrition on substantive study findings (Groves, 2006). It is obviously not possible to resolve this debate here. However, the fact that few differences emerged in the preliminary analyses that were presented here suggest that bias arising from sample attrition between the Wave 5 and Wave 6 surveys is not likely to be great. Even so, these tests are only preliminary, and as a result, it is best to keep the potential influence of non-random subject attrition in mind as the substantive findings from this study are reviewed.

The data were weighted so that information on age, sex, education and race matched the data in the most recent U.S. Census that was available at the time of the Wave 5 interviews. See Groves et al. (2004) for a detailed justification for the use of survey weights.

It is surprising to find that a number of investigators say they are assessing chronic strain but make no effort to show that the stressor they are studying is in fact persistent and ongoing. The interval between the Wave 5 and Wave 6 surveys in the current study was two years. Preliminary analysis suggest that the correlation between identical measures of financial strain at Wave 5 and Wave 6 is .577 (p < .001). Although assessing the stability of a construct over time is a complex issue (see Kessler & Greenberg 1981), this correlation coefficient provides some evidence that the financial difficulties that are assessed in this study tend to be persistent and ongoing in late life.

The Wave 5 gratitude scores ranged from 5 to 12. However, as other investigators have observed (e.g., Chipperfield, Perry, & Weiner, 2003), scores on the gratitude measure were skewed. More specifically, a frequency distribution of the gratitude scores revealed that a high proportion of older people feel grateful. Consequently, care must be taken when illustrating the nature of observed statistical interaction effects with the formulas provided by Aiken and West (1991). In particular, researchers must select scores on measures, such as gratitude, that contain a sufficient number of cases. Otherwise, the resulting estimates may be influenced by the problem of data sparseness (see Cohen et al. 2003, for a discussion of this issue). The values of 8, 10, and 12 were used to illustrate the interaction effects in the current study for the following reasons. A total of 40 older adults had a gratitude score of 8 or less, thereby providing sufficient data to illustrate the effects of relatively low levels of gratitude. A score of 10 was used because it falls midway between a value of 8 and the highest observed score of 12. A total of 221 older study participants had gratitude scores of either 9 or 10. Finally, a score of 12 was selected because it is the highest possible value of gratitude. A total of 470 older adults had the highest possible score and an additional 87 older people had a gratitude score of 11.

Some investigators might argue that financial strain erodes feelings of gratitude among older people. And if the relationship between persistent economic problems and gratitude is sufficiently large, problems may arise in estimating the interaction effect between financial strain and gratitude on depressive symptoms. Put another way, the relationship between financial strain and gratitude may be confounded with the interaction between financial strain and gratitude on symptoms of depression. This is not likely to be the case in the current study because preliminary evidence suggests that the magnitude of the correlation between financial strain and feelings of gratitude is not substantial (r = -.151; p < .001).

Emmons and Kneezel (2005) also found that more frequent prayer was associated with a greater sense of gratitude. However, care must be taken when including prayer in the analysis because there is some evidence that older people frequently offer prayers of thanksgiving (Krause & Chatters, 2005). Consequently, it is difficult to know if prayer helps people feel more grateful or whether grateful people are more likely to pray.

The data in Table 4 also reveal that the impact of gratitude at Wave 5 on gratitude at Wave 6 is: Beta = .236; p < .001. This suggests that the feelings of gratitude are not that stable over time. Greater insight into this issue can be obtained by computing the correlation between gratitude at Wave 5 on gratitude on Wave 6 after the effects of the other variables contained in Table 4 have been removed statistically (i.e., computing the partial correlation). This partial correlation is: .217. Squaring this value suggests that gratitude at Wave 5 explains approximately 4.7% of the variance in gratitude at Wave 6. It is for this reason that gratitude is not considered to be a trait in this study. This view is consistent with the observations of Peterson and Seligman (2004), who argue that, “As a trait, gratitude is expressed as an enduring thankfulness that is sustained across situations and over time” (p. 555).

Even though some investigators are concerned about the potential influence of response bias, a recent study by Wood, Maltby, Stewart, and Joseph (2008) did not find evidence that social desirability response bias influences reports of gratitude.

A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the following conference: Religious Practice and Health: What the Research Says, sponsored by the Heritage Foundation, Washington DC, December, 2008.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interaction effects. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson CD, Schoenrade P, Ventis WL. Religion and the individual: A social psychological perspective. New York: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Chipperfield JG, Perry RP, Weiner B. Discrete emotions in late life. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2003;58B:P23–P34. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.1.p23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd. Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapam S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kessler RC, Underwood Gordon L. Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Eliot CW. The apology, phaedo and crito of Plato; golden sayings of Epictetus; meditations of Marcus Aurelius: Part 2 Harvard classics. New York: P. F. Collier & Son; 1909. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA. Emotion and religion. In: Paloutzian RF, Park CL, editors. Handbook of the psychology of religion. New York: Guilford; 2005. pp. 235–252. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, Kneezel T. Giving thanks: Spiritual and religious correlates of gratitude. Journal of Psychology and Christianity. 2005;24:140–148. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, McCullough ME. Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:377–389. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, McCullough ME, Tsang JA. The assessment of gratitude. In: Lopez SJ, Snyder CR, editors. Positive psychological assessment: A handbook of models and measures. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Mancuso RA, Branigan C, Tugade MM. The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motivation and Emotion. 2000;24:237–258. doi: 10.1023/a:1010796329158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb BH. Conceptual and measurement issues in the study of coping with chronic stress. In: Gottlieb BH, editor. Coping with chronic strain. New York: Plenum; 1997. pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM. Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2006;70:646–675. [Google Scholar]

- Groves RM, Fowler FJ, Couper MP, Lepkowski JM, Singer E, Tourangeau R. Survey methodology. New York: Wiley-Interscience; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Idler E, Musick M, Ellison CG, George LK, Krause N, Levin JS, Ory M, Pargament KI, Powell LH, Williams DR, Underwood Gordon L. National Institute on Aging/Fetzer Institute Working Group brief measures of religiousness and spirituality. Research on Aging. 2003;25:327–365. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Greenberg D. Linear panel analysis: Models of quantitative change. New York: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Aging and God: Spiritual pathways to mental health in midlife and later Years. New York: Haworth Pastoral Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Stressors in highly valued roles, meaning in life, and the physical health status of older adults. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004;59B:S287–S297. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.5.s287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. God-mediated control and psychological well-being in late life. Research on Aging. 2005;27:136–164. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Gratitude toward God, stress, and health in late life. Research on Aging. 2006;28:163–183. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Aging in the church: How social relationships affect health. West Conshohocken, PA: Templeton Foundation Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Chatters LM. Exploring race differences in a multidimensional battery of prayer measures among older adults. Sociology of Religion. 2005;66:23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ. Measurement of chronic stressors. In: Cohen S, Kessler RC, Underwood Gordon L, editors. Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 102–120. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:112–127. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes de Leon C, Rapp SS, Kasl SV. Financial strain and symptoms of depression in a community sample of elderly men and women: A longitudinal study. Journal of Aging and Health. 1994;6:448–468. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Kelley JM. Measurement of stress appraisal. In: Cohen S, Kessler RC, Underwood Gordon L, editors. Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 122–147. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullin JT. The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22:337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Seligman MEP. Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RC. The blessings of gratitude: A conceptual analysis. In: Emmons RA, McCullough ME, editors. The Psychology of Gratitude. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 58–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon KM. How to Increase and Sustain Positive Emotion: The effects of expressing gratitude and visualizing vest possible selves. Journal of Positive Psychology. 2006;1:73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Spilka B, Hood RW, Hunsberger B, Gorsuch R. The psychology of religion: An empirical approach. 3rd. New York: Guilford; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stark R, Finke R. Acts of faith: Explaining the human side of religion. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Thoits PA. Dimensions of life events that influence psychological distress: An evaluation and synthesis of the literature. In: Kaplan HB, editor. Psychosocial stress: Trends in theory and research. New York: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 33–103. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins PC. Gratitude and subjective well-being. In: Emmons RA, McCullough ME, editors. The psychology of gratitude. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. pp. 167–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B. Sampling the stress universe. In: Avison WR, Gottlib I, editors. Stress and mental health: Contemporary issues and prospects for the future. New York: Plenum; 1994. pp. 77–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Joseph S, Linley PA. Coping style as a psychological resource of grateful people. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2007;26:1076–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Maltby J, Gillett R, Linley PA, Joseph S. The role of gratitude in the development of social support, stress, and depression: Two longitudinal studies. Journal of Research on Personality. 2008;42:854–871. [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Maltby J, Stewart N, Joseph S. Conceptualizing gratitude and appreciation as a unitary personality trait. Personality and Individual Differences. 2008;44:619–630. [Google Scholar]