Abstract

The direct detection of biologically relevant metals in single cells and of their speciation is a challenging task that requires sophisticated analytical developments. The aim of this article is to present the recent achievements in the field of cellular chemical element imaging, and direct speciation analysis, using proton and synchrotron radiation X-ray micro- and nano-analysis. The recent improvements in focusing optics for MeV-accelerated particles and keV X-rays allow application to chemical element analysis in subcellular compartments. The imaging and quantification of trace elements in single cells can be obtained using particle-induced X-ray emission (PIXE). The combination of PIXE with backscattering spectrometry and scanning transmission ion microscopy provides a high accuracy in elemental quantification of cellular organelles. On the other hand, synchrotron radiation X-ray fluorescence provides chemical element imaging with less than 100 nm spatial resolution. Moreover, synchrotron radiation offers the unique capability of spatially resolved chemical speciation using micro-X-ray absorption spectroscopy. The potential of these methods in biomedical investigations will be illustrated with examples of application in the fields of cellular toxicology, and pharmacology, bio-metals and metal-based nano-particles.

Keywords: synchrotron, X-ray, cell, metal, imaging, speciation

1. Introduction

A eukaryotic cell is packed with internal compartments, the organelles, where specific chemical reactions take place. There is a growing need for in situ chemical element analysis in order to understand the biochemical process involved directly in cell organelles (Navratil et al. 2006). Cell organelle sizes range from the microworld to the nanoworld; for example, mitochondria are one of the larger organelles in the eukaryotic cell, typically 0.3–1.0 µm, whereas neural vesicles can be only a few tens of nanometres large. Among the analytes to be determined are the metal ions involved in biological processes referred to here as bio-metals. The determination of intracellular distribution of bio-metals is challenging because it requires analytical methods with high sensitivity and high spatial resolution (Lobinski et al. 2006).

The chemical speciation analysis is also important to understand the reactivity of bio-metals. Chemical elements can be present in cell organelles in various forms, such as purely inorganic, or transformed into coordination compounds after cellular metabolization. For redox metals, the determination of the oxidation state will be of particular importance because they can catalyse oxidative reactions. Ideally, microanalytical methods should therefore combine high spatial resolution (in the nanometre to the micrometre range) with high detection sensitivity (ng g−1 to µg g−1) and chemical speciation capabilities such as the determination of the oxidation state. The aim of this article is to present some recent achievements in the field of cellular chemical element imaging, and direct speciation analysis, using proton and synchrotron radiation X-ray micro- and nanoanalysis.

Chemical imaging can be defined as the spatial identification and characterization of the chemical composition of a given sample. In recent decades, numerous advances have been made in the understanding of fundamental biological processes at the cellular level. However, the ability to obtain subcellular data relating to metal content is still challenging. X-ray chemical imaging holds the potential for fundamental breakthroughs in the understanding of biological systems because chemical interactions can be evidenced at the subcellular level. By examining the energies at which X-rays are emitted or absorbed, it is possible to determine the identity and chemical speciation of the elements present in a sample. The energy required to produce the X-ray emission can be provided by electron, proton or photon beams. For imaging at high spatial resolution, the beam must be focused into a small spot. Improvements to obtain small beam sizes with proton and synchrotron beams have been made over the last few years to allow chemical imaging at high lateral resolution.

Historically, the first method of X-ray microanalysis was the electron microprobe developed by Castaing (1951) based on the use of an electron microscope with an X-ray detector. Electron microprobe X-ray microanalysis is now widely used in many fields of investigation; however, the method is limited in sensitivity when applied to diluted elements such as trace metals in cells. The analytical sensitivity of X-ray microanalysis can be greatly improved by using accelerated protons (particle-induced X-ray emission (PIXE) method) or synchrotron radiation (synchrotron radiation X-ray fluorescence (SR-XRF) method). Synchrotron radiation sources also make possible chemical speciation analysis through the application of X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS method). Each one of these methods presents specific characteristics of selectivity, sensitivity and spatial resolution, which are presented in table 1 and compared with electron probe X-ray microanalysis.

Table 1.

Typical characteristics of electron, proton and synchrotron X-ray microprobes for trace element imaging, speciation and quantification in single cells (*for ultrathin samples; **for the latest generation of instruments).

| X-ray micro-analytical techniques | detection limit | spatial resolution | selectivity | quantification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| electron microprobe | ||||

| EDS (X-ray energy dispersive spectrometry) | 100–1000 µg g−1 | 0.03*–0.5 µm | multi-elemental | semi-quantitative |

| EELS (electron energy loss spectroscopy) | 1000 µg g−1 | atomic**, 0.001 µm | chemical species | |

| proton microprobe | ||||

| PIXE | 1–10 µg g−1 | 0.2**–2 µm | multi-elemental | fully quantitative (combined to BS) |

| synchrotron microprobe | ||||

| XRF | 0.1 µg g−1 | 0.1**–2 µm | multi-elemental | semi-quantitative |

| XAS | 100 µg g−1 | 1 µm | chemical species |

2. Chemical element imaging with proton beams

The proton microprobe analysis offers two important specific capabilities for trace metal analysis: imaging and quantification. The particle beam size, around 1 µm diameter, and the resulting spatial resolution are compatible with eukaryotic cells X-ray microanalysis. Moreover, the proton microprobe is more sensitive than the electron microprobe and the concentration results are fully quantitative. The proton microprobe is therefore an efficient tool to study the distribution of trace elements at the subcellular level and their role in pharmacology, physiology and toxicology (Moretto et al. 1993; Ortega 2005). The spatial resolution of proton microprobes was typically in the micrometre range, but new systems have been developed based on high-energy stability electrostatic accelerator and high demagnification electromagnetic lenses. The spatial resolution obtained can be as low as 50 nm for scanning transmission ion microscopy (STIM) analysis and from 200 to 300 nm for PIXE/backscattering spectrometry (BS) analyses, which require higher fluxes of incoming particles (Reinert et al. 2006). Such a ‘nanobeam’ has been recently installed at the AIFIRA facility (Interdisciplinary Applications of Ion Beams in Aquitaine Region) in Bordeaux-Gradignan (Barberet et al. 2009).

2.1. Particle-induced X-ray emission

Protons accelerated in the 2–4 MeV range are excellent energy sources for X-ray emission analysis. The first micro-PIXE system was developed at Harwell (Cookson et al. 1972) shortly after the introduction of the PIXE method by Johansson et al. (1970). PIXE is based on the detection of characteristic X-rays emitted by the elements of a sample when excited with an MeV ion beam. When the energy transfer of the incident particles is higher than the electron binding energy from the inner shell, ejection of these inner shell electrons occurs and results in outer shell electrons filling the vacancies and emitting X-rays. The energy of the emitted X-rays is characteristic of the excited element. It corresponds to the difference between the two electronic levels' binding energies. The emission energies of all chemical elements are tabulated, thus enabling the identification of the composition of the atoms constituting the sample. PIXE is generally performed with protons, better than with heavier particles such as alpha particles, because the ionization cross sections follow an A−4 law, where A is the atomic weight of the incoming particle. PIXE is a multi-elemental technique that offers a good sensitivity for elements with atomic numbers between 20 < Z < 35 and 75 < Z < 85. This characteristic is well suited to the detection of chemical elements of biological interest, such as essential trace elements (i.e. Mn, Fe, Cu, Zn, Se, etc.), toxic heavy metals (Hg, Pb, etc.) or pharmacological compounds (Pt). The physical processes involved in the interaction between the particle beam and the electronic shells of the atoms have been extensively described, making PIXE a standardless quantification technique. The detection limits depend on the considered element, the nature of the sample, the experimental set-up and the analytical conditions. Detection limits are usually in the µg g−1 range. The main advantage of the PIXE method, compared with electron X-ray microanalysis, is its sensitivity. The PIXE technique presents greater ionization cross sections and lower background signal than electron X-ray microanalysis. A second advantage over the other X-ray microanalytical techniques is that fully quantitative results are obtained owing to the simultaneous analysis of trace elements using PIXE and sample mass using proton BS and STIM. The term ‘fully’ quantitative refers to the fact that both the amount of trace element and the local mass of the sample are measured. The combination of STIM/PIXE/BS offers a fully quantitative distribution of all chemical elements present in a cell from hydrogen to high Z elements. The proton beam microprobe analysis is the method of choice when precise quantitative results are required at the microscopic level (Carmona et al. 2008a).

2.2. Backscattering spectrometry

BS is based on the measurement of the energy of backscattered particles after interaction with the nuclei of target atoms (Chu et al. 1978). The energy loss of incident particles is due to nuclear interactions with energy transfer decreasing for heavier nuclei and to electronic interactions with energy loss increasing with sample thickness. The BS method is particularly interesting because the incoming ions are ‘sorted’ according to the atomic nucleus they have been scattered on and according to the depth of the interaction. Therefore, this technique not only allows an elemental identification but also determines the thickness of the sample in the case of samples with known density. The BS method is sensitive to any nucleus heavier than the incoming particle, and when it is applied to biological samples, it can be used to determine the organic composition of the sample: C, N and O elements that represent up to 90 per cent of the sample mass. This is complementary to the PIXE analysis because these elements are not easily measured using PIXE. BS is also used to monitor the incoming beam current and to measure the deposited charge during analysis as part of the PIXE normalization procedure. In that case, PIXE and BS must be performed simultaneously.

2.3. Scanning transmission ion microscopy

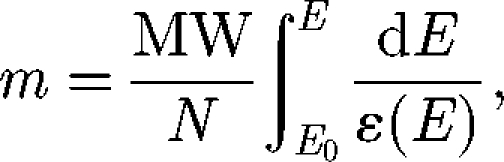

STIM quantification is based on the measurement of the energy loss of the incident particles after passing through the sample. The energy loss is proportional to the stopping power of the sample and describes its atomic density. STIM is limited to the analysis of thin samples. For biological samples, the thickness must not exceed a few microns when using MeV alpha particles and a few tens of microns with MeV protons. STIM is well suited to the analysis of single cells that are typically of the order of 10 µm thick. STIM is performed using a silicon detector placed in the beam axis very close behind the sample. This geometry results in increased detection efficiency, which enables drastic lowering of the beam current down to a few hundreds of particles per second. Therefore, high spatial resolution density maps can be obtained. Under these conditions, the sample does not suffer any mass loss and one can access the areal mass of the sample (mass of the sample per area). To do so, Paparamborde software can be used (Devès et al. 2005a). This program divides STIM spectra into several sections and calculates the mass of each one of them using the equation below. The total mass is the sum of the masses of all the sections,

|

where MW is the molecular weight of the sample, N is Avogadro's number, dE is the energy loss and ε is the corresponding stopping power at energy E. The stopping power is calculated by Bragg's rule, which states that the stopping number of the sample is the sum of the stopping numbers of all the atoms composing the sample. It implies that the chemical composition must be known and that it is obtained by BS and PIXE analyses. The stopping power is calculated according to E, because this value depends on the energy of the beam that varies when the particles are slowed down in the sample. The combination of PIXE for trace element detection, BS for charge monitoring and organic element determination in biological samples and STIM for mass determination enables the fully quantitative analysis as element content can be expressed in terms of mass ratio (mass of an element per mass of organic matrix) down to the subcellular level (Carmona et al. 2008a). STIM also enables the determination of hydrogen content, either directly by using off-axis STIM (Matsuyama et al. 2005) or indirectly when on-axis STIM is combined with BS analysis (Devès et al. 2005b). In addition to mass determination, STIM reveals the ultrastructure of single cells at the nano level (Minqin et al. 2007), which can be further correlated to the PIXE/BS chemical distributions.

2.4. Examples of application

Some pharmacological compounds are based on metal compounds. Their cellular pharmacology, i.e. effects on cellular activity such as growth inhibition, DNA synthesis inhibition, apoptosis triggering, etc., can be studied by various biochemical means, but their intracellular distribution remains difficult to characterize. The knowledge of the intracellular distribution of metal-based drugs is important in order to verify that they reach their intracellular target, such as, for example, the cell nucleus for anti-cancer compounds (Larsen et al. 2000). During the last 10 years, several studies dedicated to cancer research were carried out with proton microprobes. A large part of these applications was dedicated to study the cellular pharmacology of cis-diamminedichloroplatinum(II) (cisplatin), the leading metal compound used in cancer chemotherapy. Proton microprobe analysis showed that platinum effectively reached the nucleus of the cells exposed to cisplatin but with a low specificity (Moretto et al. 1995; Ortega et al. 1996; Mauthe et al. 1998; Sakurai et al. 2008). Trace element quantification in cisplatin-resistant cells also revealed a strong increase in the copper content (Ortega et al. 1996), which can be linked to the expression of copper transport proteins in cisplatin-resistant cells (Ishida et al. 2002). The intracellular distribution of some anti-cancer drugs based on other heteroatoms was also investigated, such as iodine in 4′-iodo-4′-deoxy-doxorubicin (Ortega et al. 1997; Ortega 2000), gallium nitrate (Ortega et al. 2003) and boron (Bench et al. 2003; Endo et al. 2006). These experiments revealed the intracellular distribution of these anti-cancer drugs and their interaction with endogenous trace metals. For example 4′-iodo-4′-deoxy-doxorubicin accumulates into the nucleus of cancer cells and induces the relocalization of iron from the cytosol to the nucleus. This result indicates the intracellular complexation of iron by doxorubicin, probably through its semiquinone chemical function, and suggests that iron–drug complexes could participate in the overall anti-cancer activity through redox cycling of Fe-semiquinone.

In the field of metal toxicology, the proton microprobe enabled the intracellular distribution of toxic metals to be determined, in a quantitative manner, and revealed the interaction of toxic metals with essential trace elements owing to its multi-element analytical capabilities. This is an important feature, as, in many cases, toxic metals may substitute for essential ions, owing to similar chemical reactivity. For example, it was recently found using proton microprobe analysis that cobalt accumulates into the nucleus and peri-nuclear region of skin human cells and induces a decrease in two essential metal ions, magnesium and zinc (Ortega et al. 2009). These results suggest that the alteration of magnesium and zinc homeostasis could participate in the cytotoxic effects of cobalt. In Sertoli cells exposed to cadmium, another toxic element, a similar decrease in the zinc content was observed together with an increase in the iron content (Kusakabe et al. 2008). A similar result was observed in hepatic cells of mice exposed to cadmium (Nakazato et al. 2008). The increase in the cellular zinc content and the decrease in iron could be involved in the toxicity of cadmium as iron excess in cells is known to catalyse pro-oxidant reactions, whereas zinc, which is not a redox metal, is an essential element involved in detoxification pathways.

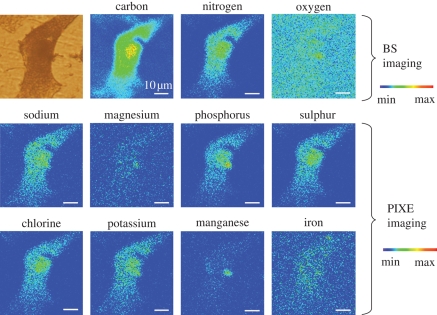

Another important field of application of the proton microprobe is the investigation of metal ions in the aetiology of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Anomalous iron handling has been proposed to be involved in the selective loss of dopaminergic neurons from the substantia nigra pars compacta in Parkinson's disease. The intracellular distribution of iron in neuromelanin-containing dopaminergic neurons has been investigated in human tissues, showing no difference in the iron content between controls and Parkinson's disease patients (Reinert et al. 2007). The combination of STIM/PIXE/BS revealed that iron distribution in dopaminergic cells exposed to an excess of iron resulted in a marked accumulation within distal ends, suggesting interaction between iron and dopamine within neurotransmitter vesicles (Carmona et al. 2008a). Combining these three ion beam techniques, Rajendran et al. (2009) have imaged amyloid plaques in freeze-dried brain sections from mice and simultaneously quantified iron, copper and zinc, showing increased metal concentrations within the amyloid plaques compared with the surrounding tissue. Preliminary results on the intracellular distribution of native iron in neurons from rat brain sections have also been reported (Fiedler et al. 2007), showing a slight increase in the iron content in neurons surrounded by perineuronal net extracellular matrix. The cellular distribution of manganese, a metal suspected to be involved in the aetiology of Parkinson's disease, is being currently investigated using the proton microprobe at the AIFIRA facility. Some preliminary results show that manganese accumulates in dopaminergic cells within peri-nuclear structures that remain to be identified (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Multi-element imaging of a single PC12 cell exposed to MnCl2 obtained at the AIFIRA facility. Carbon, nitrogen and oxygen maps were imaged using micro-BS analysis, whereas trace elements of higher Z were imaged using micro-PIXE analysis. The chemical element maps show that Mn accumulates within the perinuclear region of the cell and is colocalized with Mg. Scale bar, 10 µm.

3. Chemical element imaging with synchrotron radiation beams

3.1. Synchrotron radiation X-ray fluorescence

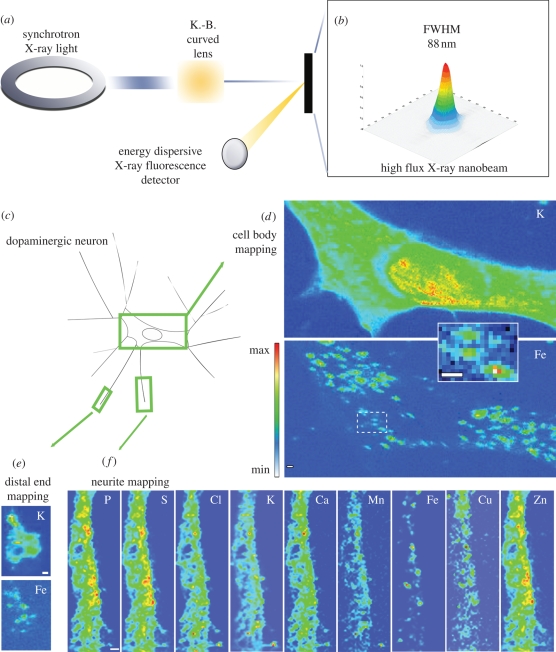

Another excellent excitation source to perform X-ray analysis is the synchrotron radiation. Similar to that of PIXE, the principle of XRF is based on the detection of X-rays emitted from sample atoms irradiated with X-rays of higher energy. XRF analysis is multi-elemental and quantitative; the intensity of the fluorescence is directly proportional to the concentration of the elements within the sample. When applied to the analysis of trace metals, high Z elements, into thin biological samples, low Z matrix, there is no need for correction of X-ray absorption into the sample. However, X-ray absorption must be addressed for the quantitative determination of light elements, typically of Z < 17. Third-generation synchrotron sources are bright enough to generate high flux microbeams, which can be applied to map trace element distributions in biological samples at the cellular scale (Twining et al. 2003; Ortega et al. 2004). However, the spatial resolution offered by the SR-XRF technique was limited until recently to approximately 1 µm. Improvements in hard X-rays (greater than 1 keV) optics have been made over the last few years. Submicron spatial resolution XRF beamlines have been recently developed at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) and European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF), enabling keV photons to be focused down to 100 nm beam size (Fahrni 2007). For example, an original experimental set-up was developed to perform chemical element imaging with an 80 nm spatial resolution using synchrotron-based XRF at ESRF on the ID22NI beamline. This spatial resolution, combined with high brightness, enables chemical element imaging in subcellular compartments with a very high sensitivity, in the attogram range, and with the unique capability to work in an air environment, as illustrated in figure 2 (Ortega et al. 2007; Carmona et al. 2008b). The large penetration depth of hard X-rays does not require specimens to be sectioned, and cells can be investigated close to their natural, hydrated state with dedicated cryogenic approaches and without introduction of artificial dyes.

Figure 2.

(a) The synchrotron XRF nanoprobe end-station installed at ESRF, on the ID22 beamline, was designed to provide a high flux (1012 ph s−1) of hard X-rays (i.e. 17 keV) with a beam size of less than 90 nm (FWHM, full width at half maximum) using a Kirkpatrick–Baez-type curved lens. The intensity distribution in the focal plane is shown in (b); dopamine-producing cells were exposed in vitro to FeSO4 for 24 h (c). Chemical element distributions were recorded on distinct cellular areas such as cell bodies (d), distal ends (e) and neurite outgrowths (f). Min–max range bar units are arbitrary. All scale bars, 1 µm. Iron was found in 200–300 nm structures in the cytosol, neurite outgrowths and distal ends, but not in the nucleus (Ortega et al. 2007).

3.2. Examples of application

The fields of application of SR-XRF are similar to that of proton microprobe X-ray analysis, with investigations in cancer chemotherapy of inorganic compounds, metal neurotoxicity and trace element physiology. In addition, the high spatial resolution obtained with recently developed instruments opens up new frontiers in the imaging of nanoparticles in cells.

The initial work of SR-XRF imaging at the subcellular level was dedicated to determining the distribution of cancer chemotherapeutic compounds, essentially platinum compounds. The synchrotron radiation imaging of cisplatin (Ilinski et al. 2003) confirmed the homogeneous distribution of platinum in cancer cells, as already demonstrated by proton microprobe analysis (Ortega et al. 1996). However, the advantage of the SR-XRF microprobe was to enable platinum imaging at lower exposure concentrations, 10 µM instead of 30 µM, which is closer to the clinically relevant concentration. In other studies, the SR-XRF microprobe was used to compare the subcellular distribution of cisplatin, which is a Pt(II) complex, and new platinum compounds based on Pt(IV) complexes (Hall et al. 2003, 2006). Both studies concluded in the similar distribution of ciplatin and Pt(IV) compounds in cancer cells with intranuclear accumulation.

Owing to the high detection sensitivity of SR-XRF nanoprobes, some important achievements have occurred in the field of trace element physiopathology. For example, the copper intracellular distribution could be mapped in NIH 3T3 with cells at beamline 2-ID-D of the APS at the Argonne National Laboratory with a 200 nm × 200 nm beam spot (Yang et al. 2005). SR-XRF microscopy supports the existence of a labile copper pool, which appears to be localized in mitochondria and the Golgi apparatus. A very important discovery on copper angiogenesis was also reported using the same experimental device (Finney et al. 2007). SR-XRF microscopy revealed a dramatic spatial relocalization specific to capillary formation of 80–90% of endogenous cellular copper stores from intracellular compartments to the tips of nascent endothelial cell filopodia and across the cell membrane. The same copper accumulation was observed in filopodia from PC12 dopaminergic cells after in vitro differentiation, this time by using the SR-XRF nanoprobe at ESRF on the ID22NI beamline (Carmona et al. 2008b). This study also surprisingly revealed the presence of Pb at the ultratrace level, 5.10−21 g per pixel of 100 nm size, in these copper-rich thin neurite outgrowths. The chemical imaging of PC12 cells with the ID22NI nanoprobe at ESRF has revealed the accumulation of iron in dopamine vesicles, as illustrated in figure 2 (Ortega et al. 2007). This same SR-XRF nanoprobe was also used to follow the elemental composition of intracellular neuromelanin in neurons from human samples during development (Bohic et al. 2008). In a study of the distribution of chemical elements in hypoxia-injured neurons, changes in the cellular elemental content were observed, with an increase in Fe, Cu and Zn, which could represent an early cell response after injury (Duong et al. 2009). Another breakthrough in trace element physiology owing to SR-XRF chemical imaging is the discovery of the specific role of selenium in spermatogenesis using the beamline 2-ID-E of the APS at the Argonne National Laboratory (Kehr et al. 2009). A dramatic Se enrichment was observed in late spermatids from mice seminiferous tubules. This enrichment was due to elevated levels of the mitochondrial form of glutathione peroxidase 4 and was fully dependent on the supplies of Se by selenoprotein P. SR-XRF allowed the quantification of Se in the midpiece (0.8 fg) and head (0.14 fg) of individual sperm cells, revealing the ability of sperm cells to handle the amounts of this element well above its typically toxic levels. The SR-XRF nanoprobe was also useful in determining the intracellular distribution of chemical elements in microorganisms such as marine protists, showing the importance of iron to photosynthetic machinery and of zinc to nuclear organelles (Twining et al. 2008).

A new field of investigation that could be initiated using the high spatial resolution of last generation SR-XRF nanoprobes is the imaging of nanoparticles in single cells. Oligonucleotide-modified nanoparticles, which consist of oligonucleotide DNA covalently attached to TiO2 nanoparticles, are emerging tools to manipulate intracellular biochemical processes. Initial work on TiO2 nanoparticles using SR-XRF shows the intracellular accumulation of these nanocomposites, revealing their potential usefulness in gene therapy (Paunesku et al. 2003). Paunesku et al. (2007) investigated the intracellular distribution of nanoconjugates composed of DNA oligonucleotides attached to TiO2 nanoparticles matching mitochondrial or nucleolar DNA. SR-XRF imaging confirmed that they were specifically retained in the mitochondria or nucleoli, thus creating a locally increased concentration of the oligonucleotide. In other studies, nanoconjugates composed of TiO2 nanoparticles with DNA oligonucleotides and a gadolinium contrast agent were synthesized for use in magnetic resonance imaging (Endres et al. 2008; Paunesku et al. 2008). Transfection of cultured cancer cells with these nanoconjugates showed them to be superior to the free contrast agent of the same formulation with regard to intracellular accumulation, retention and subcellular localization. SR-XRF can be used not only to confirm the intracellular distribution of nanoparticles, but also as a unique tool to quantify intracellular nanoparticles (Thurn et al. 2009). The toxicology of nanoparticles was investigated using micro-SR-XRF, showing an excess of calcium in macrophages exposed to carbon nanotubes (Bussy et al. 2008). In a different field of application, uranium biogenic nanoparticles were evidenced in the outer membrane of metal-reducing bacteria (Marshall et al. 2006).

4. Chemical element speciation with synchrotron radiation beams

4.1. X-ray absorption spectroscopy

Hard XAS is element oxidation state and symmetry specific. It is one of the most widely used techniques for investigating the local structural environment of metal ions. It is usually applied at synchrotron radiation facilities, providing intense and tunable X-ray beams. X-ray absorption spectra are obtained by tuning the photon energy around the absorption edge of a specific element. Each core electron has a well-defined binding energy, and when the energy of the incident X-ray is scanned across one of these energies, there is an abrupt increase in absorption. Local structural information on the absorber element can be deduced by analysing oscillations in X-ray absorption versus photon energy that are caused by the scattering of the X-ray excited photoelectron. XAS can be divided into X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES), which provides information primarily about geometry and oxidation state, and extended X-ray absorption fine structure, which provides information about metal site ligation. XAS is usually performed by measuring the photons transmitted through the sample; however, for dilute analytes, such as trace metals in biological samples, XAS is performed in the fluorescence mode, which is much more sensitive than the absorption spectroscopy (Gunter et al. 2002).

Up to now, XAS was mainly used with unfocused beams. It has been particularly useful for the bulk chemical speciation of dilute samples of biological concern. The recent development of hard X-ray optics, discussed in the previous section, has enabled the application of XAS, especially XANES, to the single cell. When performed with a microbeam, μ-XANES enables the direct speciation analysis of chemical elements in subcellular compartments, thus avoiding cell fractionation and other preparation steps that might modify the chemical species (Bacquart et al. 2007).

4.2. Examples of application

The μ-XANES probe is a quite unique tool to estimate the redox state of chemical elements in cells. However, up to now, there are still very few examples of X-ray absorption spectrometry applied to cellular compartments, probably because this technique still requires long acquisition times and beam damage is of particular concern. In 2001, we demonstrated the feasibility of μ-XANES analysis on single cells by examining the iron oxidation state in cancer cells exposed to doxorubicin, an anti-cancer anthracycline known to complex iron (Ortega et al. 2001). We found that iron was present as Fe(III) in the nucleus of cultured cancer cells with spectral features similar to that of Fe–doxorubicin complexes, but different from the main iron-storage protein, ferritin. μ-XANES was also applied to the chemical speciation of platinum anti-cancer drugs (Hall et al. 2003), showing that Pt(IV) complexes are readily reduced to Pt(II) in cells, except some specific compounds such as iproplatin that can stand in its oxidized form inside cells. The technique was also used for the single cell determination of metal redox states in prokayotes (Kemner et al. 2004). μ-XANES also revealed the existence of intracellular granules containing ferric and ferrous iron formed in Shewanella putrefaciens (Glasauer et al. 2007). In trace element physiology of eukaryotic cells, μ-XANES performed on a copper-loaded NIH 3T3 cell revealed at all tested subcellular locations a near-edge feature that is characteristic for monovalent copper (Yang et al. 2005).

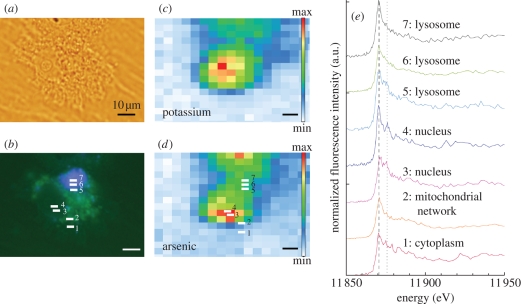

Intracellular redox states are important parameters in understanding metal carcinogenesis and toxicology. The imaging of chromium oxidation states was compared in cells exposed to soluble and low solubility chromate compounds, showing the intracellular reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) in all cell compartments except in perinuclear structures from low solubility compounds (Ortega et al. 2005). The μ-XANES technique was also used to investigate the oxidation state of iron (Bacquart et al. 2007; Chwiej et al. 2007) and copper (Chwiej et al. 2008) in neurons. The comparison of the absorption spectra near the iron K-edge measured in melanized neurons from the substantia nigra of patients with Parkinson's disease and of control samples did not show significant differences in iron or copper oxidation states. In order to accurately identify intracellular compartments, we have recently coupled the tracking of cellular organelles in a single cell by confocal and epifluorescence microscopy with local analysis of chemical species by μ-XANES. This original methodology enabled the direct speciation analysis of arsenic in subcellular organelles with a 10−15 g detection limit (Bacquart et al. 2007). μ-XANES shows that As(III) is the main form of arsenic in the cytosol, nucleus and mitochondrial network of HepG2 cells exposed to As(OH)3. In some cases, oxidation to a pentavalent inorganic form is observed in nuclear structures of HepG2 cells (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Normalized XANES spectra at arsenic K-absorption edge in the cytosol, mitochondrial network, nucleus and lysosomes of HepG2 cells exposed to As(OH)3. Light microscopy of a single cell (a); epifluorescence microscopy of the same cell showing in green the mitochondrial network (labelled with rhodamine 123) and in blue the lysosomes (labelled with lysotracker) (b); micro-XRF distribution of potassium (c) and arsenic (d). XANES spectra in the subcellular compartments show that the main arsenic oxidation state is As(III) in all organelles, with a mixture of trivalent and pentavalent arsenic in the nucleus (e).

5. Conclusions and perspectives

Chemical imaging with X-ray microprobes offers a means of investigating the distribution and speciation of bio-metals in single cells with a detection sensitivity and a spatial resolution well suited to explore subcellular interactions. Several chemical nanoimaging instruments are under development worldwide, principally on third-generation synchrotron facilities in the USA, Japan and also in Europe (France, Germany, Spain, UK, etc.). The same is true for the proton nanoprobe community. It is likely that fundamental breakthroughs in our understanding of basic chemical processes in biology will be achieved in the next few years owing to these new instruments. Real breakthroughs have already been obtained in the understanding of the physiological functions of trace elements such as for the role of Cu in angiogenesis or selenium in spermatogenesis. Important achievements have also been reached in the fields of redox metal toxicology, neurochemistry, carcinogenesis and cellular pharmacology. The application to nanotechnology research is really promising as the X-ray microanalytical techniques are quite unique tools for validating intracellular targets and for quantification of metal-based nanoparticles. One exciting research area where the X-ray nanoprobes will continue to open new frontiers is the study of intracellular preferential localization of trace elements. From the examples of subcellular chemical imaging listed in this article, it can be concluded that in many cases cellular organelles are characterized by a specific chemical element composition, which is related to the specific functions of the organelles (i.e. energy production in the mitochondria requires Fe and Cu involved in metalloenzymes). The same is true for the subcellular distribution of toxic metals that are stored within intracellular compartments such as the Golgi apparatus or the lysosomes for detoxification purposes. The relationship between the specific cellular functions of organelles and their chemical element composition can be considered as part of the chemotype that characterizes each living system, as suggested by Williams (2007).

Footnotes

One contribution of 13 to a Theme Supplement ‘Biological physics at large facilities’.

References

- Bacquart T., Devès G., Carmona A., Tucoulou R., Bohic S., Ortega R. 2007. Subcellular speciation analysis of trace element oxidation states using synchrotron radiation micro-X-ray absorption near edge structure. Anal. Chem. 79, 7353–7359. ( 10.1021/ac0711135) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barberet Ph., Incerti S., Andersson F., Delalee F., Serani L., Moretto Ph. 2009. Technical description of the CENBG nanobeam line. Nucl. Instr. Methods B 267, 2003–2007. ( 10.1016/j.nimb.2009.03.077) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bench G., Grant P. G., Ueda D. L., Autry-Conwell S. A., Hou Y., Boggan J. E. 2003. Assessment of proton microbeam analysis of 11B for quantitative microdistribution analysis of boronated neutron capture agents in biological tissues. Radiat. Res. 160, 667–676. ( 10.1667/RR3085) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohic S., Murphy K., Paulus W., Cloetens P., Salomé M., Susini J., Double K. 2008. Intracellular chemical imaging of the developmental phases of human neuromelanin using synchrotron X-ray microspectroscopy. Anal. Chem. 80, 9557–9566. ( 10.1021/ac801817k) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussy C., et al. 2008. Carbon nanotubes in macrophages: imaging and chemical analysis by X-ray fluorescence microscopy. Nano Lett. 8, 2659–2663. ( 10.1021/nl800914m) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona A., Devès G., Ortega R. 2008a. Quantitative micro-analysis of metal ions in subcellular compartments of cultured dopaminergic cells by combination of three ion beam techniques. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 390, 1585–1594. ( 10.1007/s00216-008-1866-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona A., Cloetens P., Devès G., Bohic S., Ortega R. 2008b. Nano-imaging of trace metals by synchrotron X-ray fluorescence into dopaminergic single cells and neurite-like processes. J. Anal. At. Spectrom. 23, 1083–1088. ( 10.1039/b802242a) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castaing R. 1951. Application des sondes électroniques à une méthode d'analyse ponctuelle chimique et cristallographique., Thèse de doctorat d’état, Université de Paris, 1952, Publication ONERA N. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Chu W. K., Mayer J. W., Nicolet M. A. 1978. Backscattering spectrometry. Orlando, FL: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chwiej J., Adamek D., Szczerbowska-Boruchowska M., Krygowska-Wajs A., Wojcik S., Falkenberg G., Manka A., Lankosz M. 2007. Investigations of differences in iron oxidation state inside single neurons from substantia nigra of Parkinson's disease and control patients using the micro-XANES technique. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 12, 204–211. ( 10.1007/s00775-006-0179-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chwiej J., Adamek D., Szczerbowska-Boruchowska M., Krygowska-Wajs A., Bohic S., Lankosz M. 2008. Study of Cu chemical state inside single neurons from Parkinson's disease and control substantia nigra using the micro-XANES technique. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 22, 183–188. ( 10.1016/j.jtemb.2008.03.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookson J. A., Ferguson A. T. G., Piling F. D. 1972. Proton micro-beams, their production and use. J. Radioanal. Chem. 12, 39–52. ( 10.1007/BF02520973) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devès G., Michelet-Habchi C., Ortega R. 2005a. Paparamborde: a software dedicated to quantitative mapping of biological samples using scanning transmission ion microscopy. Nucl. Instr. Methods B 231, 136–141. ( 10.1016/j.nimb.2005.01.047) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devès G., Isaure M. P., Le Lay P., Bourguignon J., Ortega R. 2005b. Fully quantitative imaging of chemical elements in Arabidopsis thaliana tissues and single cells using STIM, PIXE and RBS. Nucl. Instr. Methods B 231, 117–122. ( 10.1016/j.nimb.2005.01.044) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Duong T. T., Witting P. K., Antao S. T., Parry S. N., Kennerson M., Lai B., Vogt S., Lay P. A., Harris H. H. 2009. Multiple protective activities of neuroglobin in cultured neuronal cells exposed to hypoxia re-oxygenation injury. J. Neurochem. 108, 1143–1154. ( 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05846.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo K., et al. 2006. Demonstration of inter- and intracellular distribution of boron and gadolinium using micro-proton-induced X-ray emission (Micro-PIXE). Oncol. Res. 16, 57–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endres P. J., MacRenaris K. W., Vogt S., Meade T. J. 2008. Cell-permeable MR contrast agents with increased intracellular retention. Bioconjug. Chem. 19, 2049–2059. ( 10.1021/bc8002919) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrni C. J. 2007. Biological applications of X-ray fluorescence microscopy: exploring the subcellular topography and speciation of transition metals. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 11, 121–127. ( 10.1016/j.cbpa.2007.02.039) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler A., Reinert T., Morawski M., Brückner G., Arendt T., Butz T. 2007. Intracellular iron concentration of neurons with and without perineuronal nets. Nucl. Instr. Methods B 260, 153–158. ( 10.1016/j.nimb.2007.02.069) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finney L., et al. 2007. X-ray fluorescence microscopy reveals large-scale relocalization and extracellular translocation of cellular copper during angiogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 2247–2252. ( 10.1073/pnas.0607238104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasauer S., Langley S., Boyanov M., Lai B., Kemner K., Beveridge T. J. 2007. Mixed-valence cytoplasmic iron granules are linked to anaerobic respiration. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 993–996. ( 10.1128/AEM.01492-06) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunter K. K., Miller L. M., Aschner M., Eliseev R., Depuis D., Gavin C. E., Gunter T. E. 2002. XANES spectroscopy: a promising tool for toxicology: a tutorial. Neurotoxicology 23, 127–146. ( 10.1016/S0161-813X(02)00034-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M. D., Dillon C. T., Zhang M., Beale P., Cai Z., Lai B., Stampfl A. P., Hambley T. W. 2003. The cellular distribution and oxidation state of platinum(II) and platinum(IV) antitumour complexes in cancer cells. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 8, 726–732. ( 10.1007/s00775-003-0471-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall M. D., Alderden R. A., Zhang M., Beale P. J., Cai Z., Lai B., Stampfl A. P., Hambley T. W. 2006. The fate of platinum(II) and platinum(IV) anti-cancer agents in cancer cells and tumours. J. Struct. Biol. 155, 38–44. ( 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.01.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilinski P., et al. 2003. The direct mapping of the uptake of platinum anticancer agents in individual human ovarian adenocarcinoma cells using a hard X-ray microprobe. Cancer Res. 63, 1776–1179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida S., Lee J., Thiele D. J., Herskowitz I. 2002. Uptake of the anticancer drug cisplatin mediated by the copper transporter Ctr1 in yeast and mammals. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14 298–14 302. ( 10.1073/pnas.162491399) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson T. B., Aklesson R., Johansson S. A. E. 1970. X-ray analysis: elemental trace analysis at the 10−12 g level. Nucl. Instr. Methods 84, 141–143. ( 10.1016/0029-554X(70)90751-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kehr S., et al. 2009. X-ray fluorescence microscopy reveals the role of selenium in spermatogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 389, 808–818. ( 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.04.024) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemner K. M., et al. 2004. Elemental and redox analysis of single bacterial cells by X-ray microbeam analysis. Science 306, 686–687. ( 10.1126/science.1103524) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusakabe T., Nakajima K., Nakazato K., Suzuki K., Takada H., Satoh T., Oikawa M., Arakawa K., Nagamine T. 2008. Changes of heavy metal, metallothionein and heat shock proteins in Sertoli cells induced by cadmium exposure. Toxicol. In Vitro 22, 1469–1475. ( 10.1016/j.tiv.2008.04.021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen A. K., Escargueil A. E., Skladanowski A. 2000. Resistance mechanisms associated with altered intracellular distribution of anticancer agents. Pharmacol. Ther. 85, 217–229. ( 10.1016/S0163-7258(99)00073-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobinski R., Moulin C., Ortega R. 2006. Imaging and speciation of trace elements in biological environment. Biochimie 88, 1591–1604. ( 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.10.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M. J., et al. 2006. c-Type cytochrome-dependent formation of U(IV) nanoparticles by Shewanella oneidensis. PLoS Biol. 4, e268 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040268) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuyama S., et al. 2005. Microbeam analysis of single aerosol particles at Tohoku university. Int. J. PIXE 15, 257–262. ( 10.1142/S0129083505000593) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mauthe R. J., Sideras-Haddad E., Turteltaub K. W., Bench G. 1998. Quantitative imaging microscopy for the sensitive detection of administered metal containing drugs in single cells and tissue slices—a demonstration using platinum based chemotherapeutic agent. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 17, 651–663. ( 10.1016/S0731-7085(97)00225-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minqin R., van Kan J. A., Bettiol A. A., Daina L., Gek C. Y., Huat B. B., Whitlow H. J., Osipowicz T., Watt F. 2007. Nano-imaging of single cells using STIM. Nucl. Instr. Methods B 260, 124–129. ( 10.1016/j.nimb.2007.02.015) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moretto Ph., Llabador Y., Ortega R., Simonoff M., Razafindrabe L. 1993. PIXE microanalysis in human cells: physiology and pharmacology. Nucl. Instr. Methods B 75, 511–517. ( 10.1016/0168-583X(93)95705-A) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moretto Ph., Ortega R., Llabador Y., Simonoff M., Bénard J. 1995. Nuclear microanalysis of platinum and trace elements in cisplatin-resistant human ovarian adenocarcinoma cells. Nucl. Instr. Methods B 104, 292–298. ( 10.1016/0168-583X(95)00407-6) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazato K., Nagamine T., Suzuki K., Kusakabe T., Moon H. D., Oikawa M., Sakai T., Arakawa K. 2008. Subcellular changes of essential metal shown by in-air micro-PIXE in oral cadmium-exposed mice. Biometals 21, 83–91. ( 10.1007/s10534-007-9095-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navratil M., Mabbott G. A., Arriaga E. A. 2006. Chemical microscopy applied to biological systems. Anal. Chem. 78, 4005–4019. ( 10.1021/ac0606756) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega R. 2000. Intracellular distributions of the anthracycline 4’-iodo-4’-deoxy-doxorubicin and essential trace metals using nuclear microprobe analysis. Polycycl. Aromat. Comp. 21, 99–108. ( 10.1080/10406630008028527) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega R. 2005. Chemical elements distribution in cells. Nucl. Instr. Methods B 231, 218–223. ( 10.1016/j.nimb.2005.01.060) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega R., Moretto Ph., Fajac A., Bénard J., Llabador Y., Simonoff M. 1996. Quantitative mapping of platinum and essential trace metal in cisplatin resistant and sensitive human ovarian adenocarcinoma cells. Cell. Mol. Biol. 42, 77–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega R., Moretto Ph., Llabador Y., Simonoff M. 1997. Nuclear microprobe analysis of iodine and iron distributions in tumor cells exposed to the anthracycline 4′-iodo-4′-deoxydoxorubicin. Nucl. Instr. Methods B 130, 426–430. ( 10.1016/S0168-583X(97)00345-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega R., Devès G., Bohic S., Simionovici A., Ménez B., Bonnin-Mosbah M. 2001. Iron distribution in cancer cells following doxorubicin exposure using proton and X-ray synchrotron radiation microprobes. Nucl. Instr. Methods B 181, 480–484. ( 10.1016/S0168-583X(01)00476-1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega R., Suda A., Devès G. 2003. Nuclear microprobe imaging of gallium nitrate in cancer cells. Nucl. Instr. Methods B 210, 364–367. ( 10.1016/S0168-583X(03)01052-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega R., Bohic S., Tucoulou R., Somogyi A., Devès G. 2004. Micro-chemical element imaging of yeast and human cells using synchrotron X-ray microprobe with Kirkpatrick–Baez optics. Anal. Chem. 76, 309–314. ( 10.1021/ac035037r) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega R., Fayard B., Salomé M., Devès G., Susini J. 2005. Chromium oxidation state imaging in mammalian cells exposed in vitro to soluble or particulate chromate compounds. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 18, 1512–1519. ( 10.1021/tx049735y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega R., Cloetens P., Devès G., Carmona A., Bohic S. 2007. Iron storage in neurovesicles revealed by chemical nano-imaging. PLoS ONE 2, e925 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0000925) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega R., et al. 2009. Cobalt distribution in keratinocyte cells indicates nuclear and perinuclear accumulation and interaction with magnesium and zinc homeostasis. Toxicol. Lett. 188, 26–32. ( 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.02.024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paunesku T., et al. 2003. Biology of TiO2-oligonucleotide nanocomposites. Nat. Mater. 2, 343–346. ( 10.1038/nmat875) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paunesku T., et al. 2007. Intracellular distribution of TiO2-DNA oligonucleotide nanoconjugates directed to nucleolus and mitochondria indicates sequence specificity. Nano Lett. 7, 596–601. ( 10.1021/nl0624723) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paunesku T., et al. 2008. Gadolinium-conjugated TiO2-DNA oligonucleotide nanoconjugates show prolonged intracellular retention period and T1-weighted contrast enhancement in magnetic resonance images. Nanomedicine 4, 201–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran R., Minqin R., Ynsa M. D., Casadesus G., Smith M. A., Perry G., Halliwell B., Watt F. 2009. A novel approach to the identification and quantitative elemental analysis of amyloid deposits—insights into the pathology of Alzheimer's disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 382, 91–95. ( 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.02.136) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert T., Spemann D., Morawski M., Arendt T. 2006. Quantitative trace element analysis with sub-micron lateral resolution. Nucl. Instr. Methods B 249, 734–737. ( 10.1016/j.nimb.2006.03.129) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert T., Fiedler A., Morawski M., Arendt T. 2007. High resolution quantitative element mapping of neuromelanin-containing neurons. Nucl. Instr. Methods B 260, 227–230. ( 10.1016/j.nimb.2007.02.070) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai S. H., Okamoto M., Hasegawa M., Satoh T., Oikawa M., Kamiya T., Arakawa K., Nakano T. 2008. Direct visualization and quantification of the anticancer agent, cis-diamminedichloro-platinum(II), in human lung cancer cells using in-air microparticle-induced X-ray emission analysis. Cancer Sci. 99, 901–904. ( 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00755.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurn K. T., et al. 2009. Labeling TiO2 nanoparticles with dyes for optical fluorescence microscopy and determination of TiO2-DNA nanoconjugate stability. Small 5, 1318–1325. ( 10.1002/smll.200801458) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twining B. S., Baines S. B., Fisher N. S., Maser J., Vogt S., Jacobsen C., Tovar-Sanchez A., Sañudo-Wilhelmy S. A. 2003. Quantifying trace elements in individual aquatic protist cells with a synchrotron X-ray fluorescence microprobe. Anal. Chem. 75, 3806–3816. ( 10.1021/ac034227z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twining B. S., Baines S. B., Vogt S., de Jonge M. D. 2008. Exploring ocean biogeochemistry by single-cell microprobe analysis of protist elemental composition. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 55, 151–162. ( 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00320.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. J. 2007. A system's view of the evolution of life. J. R. Soc. Interface 4, 1049–1070. ( 10.1098/rsif.2007.0225) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., McRae R., Henary M. M., Patel R., Lai B., Vogt S., Fahrni C. J. 2005. Imaging of the intracellular topography of copper with a fluorescent sensor and by synchrotron X-ray fluorescence microscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 11 179–11 184. ( 10.1073/pnas.0406547102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]