Abstract

Background:

To analyse the correlation between pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels and clinical–pathological parameters in patients with endometrial cancer and to assess the value of plasma fibrinogen as a prognostic parameter.

Methods:

Within a retrospective multi-centre study, the records of 436 patients with endometrial cancer were reviewed and pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels were correlated with clinical–pathological parameters and patients’ survival.

Results:

The mean (s.d.) pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen level was 388.9 (102.4) mg per 100 ml. Higher plasma fibrinogen levels were associated with advanced tumour stage (FIGO I vs II vs III and IV, P=0.002), unfavourable histological subtype (endometrioid vs non-endometrioid histology, P=0.03), and higher patients’ age (⩽67 years vs >67 years, P=0.04), but not with higher histological grade (G1 vs G2 vs G3, P=0.2). In a multivariate analysis, tumour stage (P<0.001 and P<0.001), histological grade (P=0.009 and P=0.002), patients’ age (P=0.001 and P<0.001), and pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels (P=0.04 and P=0.02) were associated with disease-free and overall survival, respectively.

Conclusion:

Plasma fibrinogen levels can be used as an independent prognostic parameter for the disease-free and overall survival of patients with endometrial cancer.

Keywords: fibrinogen, endometrial cancer, prognosis

The association between cancer and haemostasis, as well as inflammation, is widely accepted (Dvorak, 1986; Andreasen et al, 2000; Balkwill and Mantovani, 2001; Coussens and Werb, 2002). A number of procoagulant and fibrinolytic factors have been found to be overexpressed in malignant human and animal tumour cells (Dvorak, 1986; Brown et al, 1988; Bardos et al, 1996).

One of these factors is fibrinogen, a plasma glycoprotein that is mainly responsible for the formation of a meshwork of fibrin monomers that consolidates an initial platelet plug into a solid haemostatic clot (Hantgan et al, 2001). As one of several acute-phase reactant proteins, it rises during systemic inflammation and tissue injury (Holm and Godal, 1984). Fibrinogen is mainly produced by hepatocytes; however, extrahepatical synthesis by epithelial cells and tumour cells has been described (Lawrence and Simpson-Haidaris, 2004).

Extensive studies on human and animal tumour biology indicate a specific link between fibrinogen and the progressive and metastatic behaviour of tumour cells (Palumbo et al, 2000, 2002, 2005; Simpson-Haidaris and Rybarczyk, 2001). Recent studies showed a correlation between elevated plasma fibrinogen levels and tumour progression in patients with gastric (Lee et al, 2004; Yamashita et al, 2005, 2006), oesophageal (Takeuchi et al, 2007), non-small-cell lung (Jones et al, 2006), breast, ovarian (Von Tempelhoff et al, 2000), and cervical cancer (Polterauer et al, 2009).

Regarding endometrial cancer, a hypercoagulable state is known to be associated with advanced tumour stage and higher histological grade (Von Tempelhoff et al, 2000). In a small series of patients with endometrial cancer (n=70), pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels correlated with tumour stage but not with patients’ survival (Von Tempelhoff et al, 2000). The aim of this study was to analyse the correlation between pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels and clinical–pathological parameters in patients with endometrial cancer and to assess the value of plasma fibrinogen as a prognostic parameter in a large multi-centre trial.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 436 consecutive patients with endometrial cancer, treated at the Departments of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at the Medical University of Vienna (n=360) and at the Landeskrankenhaus Klagenfurt (n=76) between December 1995 and June 2008, were enrolled in this study. Clinical and laboratory data were extracted retrospectively from patient files.

Clinical management

Diagnosis of endometrial cancer was established by dilation and curettage. Subsequently, patients were surgically staged according to the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO)/American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) classification system.

Hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, cytological examination of peritoneal fluid, and biopsy of any suspicious intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal lesions were performed. Pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy was conducted, except for tumour stage Ia and Ib with histological grades 1 and 2 and endometrioid histology. In patients with intermediate-risk or high-risk disease, adjuvant radiotherapy was provided according to standardised treatment protocols (Nag et al, 2000). A regimen of adjuvant chemotherapy using carboplatin/paclitaxel was used in selected patients with advanced disease.

At 3 months after completion of primary therapy, the first follow-up visit was scheduled. Patients had follow-up visits at 3-month intervals for the following 3 years, including inspection, vaginal–rectal palpation, and serum tumour marker evaluation. In the fourth and fifth year, visits were scheduled bi-annually, and once a year from the sixth to the tenth year after primary therapy. When patients did not present for scheduled follow-up visits, they were contacted by administrative personnel or nurses. When any clinically suspicious finding and/or tumour marker elevation was observed, computed tomography was performed. Recurrent disease was diagnosed histologically or by the presence of a measurable lesion on computed tomography.

Measurement of fibrinogen and other laboratory parameters

The analysis of plasma fibrinogen levels, serum CA 125, white blood cell count, and platelet count was routinely performed before therapy. Blood samples (citrated plasma) were obtained by peripheral venous puncture before surgery. Plasma fibrinogen levels were determined by the Clauss method (Clauss, 1957) using clotting reagents from Diagnostica Stago (Asnieres, France). The manufacturer claims an intra-assay variability of 3.5%. Plasma fibrinogen levels between 180 and 390 mg per 100 ml were defined as normal. For serum CA 125, a cutoff value of 40 U ml–1 has been determined, as described previously (Hsieh et al, 2002). Cutoff values for white blood cell count (1 × 1010 μl–1) and platelet count (450 000 μl–1) were used according to standardised guidelines for leukocytosis and thrombocytosis.

Statistical analysis

Values are given as means (s.d.). The t-tests and one-way ANOVA were used to compare fibrinogen plasma levels and clinical–pathological parameters. Survival probabilities were calculated by the product limit method of Kaplan–Meier. Differences between groups were tested using the log-rank test. Results were analysed for the end point of disease-free and overall survival. Events were defined as death or progression at the time of the last follow-up visit. Survival times of disease-free patients or patients with stable disease were censored with the last follow-up-date, and patients with death causes other than endometrial cancer were censored with the date of death. Univariate and multivariate Cox regression models for disease-free and overall survival were performed, comprising FIGO tumour stage (FIGO I vs FIGO II vs FIGO III and IV), histological grade (G1 vs G2 vs G3), histological subtype (endometrioid adenocarcinoma vs non-endometrioid carcinoma, such as serous and clear cell carcinoma), and pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels. The P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. We used the statistical software SPSS 16.0 for Mac (SPSS 16.0.1, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) for statistical analysis.

Institutional review board

This study was approved by our institutional review board, by the Ethics-Committee of the Medical University of Vienna, and by the Vienna General Hospital (AKH).

Results

Patients’ characteristics are given in Table 1. The mean (s.d.) pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen level was 388.9 (102.4) mg per 100 ml. Lymph node status was available in 180 patients. Lymph node involvement was noted in 26 patients. In all, 168 patients received adjuvant radiotherapy, and 35 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy.

Table 1. Patients’ characteristics.

| Parameter | Number (%) or mean (s.d.) |

|---|---|

| Total number of patients enrolled | 436 |

| Age at first diagnosis (years) | 66.9 (11.2) |

| Tumour stage | |

| FIGO Ia | 69 (15.8) |

| FIGO Ib | 191 (43.8) |

| FIGO Ic | 67 (15.4) |

| FIGO IIa | 17 (3.9) |

| FIGO IIb | 23 (5.3) |

| FIGO IIIa | 29 (6.7) |

| FIGO IIIb | 4 (0.9) |

| FIGO IIIc | 24 (5.5) |

| FIGO IVa | 3 (0.7) |

| FIGO IVb | 9 (2.0) |

| Histological grade | |

| G1 | 190 (43.6) |

| G2 | 151 (34.6) |

| G3 | 95 (21.8) |

| Histological subtype | |

| Endometrioid histology | 408 (93.6) |

| Non-endometrioid histology (clear cell, serous carcinoma) | 28 (6.4) |

| Time of follow-up (months) | 36.1 (31.1) |

| Recurrence status | |

| Number of patients with recurrent disease | 76 (17.4) |

| Time to recurrent disease (months) | 19.9 (18.9) |

| Status at last observation | |

| Disease-free | 340 (78.0) |

| Stable disease | 22 (5.0) |

| Progressive disease | 42 (9.6) |

| Tumour-related death | 20 (4.6) |

| Death related to other causes | 12 (2.8) |

Abbreviation: FIGO=International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

The correlation between pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels and clinical–pathological parameters is given in Table 2. Higher pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels were associated with advanced tumour stage, unfavourable histological subtype, and higher patients’ age, but not with higher histological grade. Pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels were significantly associated with serum CA 125, white blood cell count, and platelet count (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean plasma fibrinogen levels in patients with endometrial cancer broken down by clinical–pathological and laboratory parameters.

| Mean (s.d.) plasma fibrinogen levels (mg per 100 ml) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|

| FIGO tumour stage a | 0.002 | |

| I | 379.7 (99.6) | |

| II | 400.4 (87.8) | |

| III and IV | 425.8 (114.9) | |

| Histological grade a | 0.2 | |

| G1 | 385.8 (104.8) | |

| G2 | 383.2 (99.3) | |

| G3 | 405.6 (100.9) | |

| Histological subtype b | 0.03 | |

| Endometrioid histology | 386.1 (98.5) | |

| Non-endometrioid histology | 429.1 (144.8) | |

| Age b | 0.04 | |

| ⩽67 years | 379.3 (100.3) | |

| >67 years | 398.9 (103.8) | |

| CA 125 b | 0.02 | |

| ⩽40 U ml–1 | 399.6 (87.7) | |

| >40 U ml–1 | 432.2 (124.8) | |

| White blood cells b | 0.002 | |

| ⩽1 × 1010 μl–1 | 384.2 (97.4) | |

| >1 × 1010 μl–1 | 442.7 (129.6) | |

| Platelets b | <0.001 | |

| ⩽450 000 μl–1 | 385.3 (96.9) | |

| >450 000 μl–1 | 563.0 (163.04) | |

Abbreviation: FIGO=International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

One-way ANOVA.

Independent two-sided t-test.

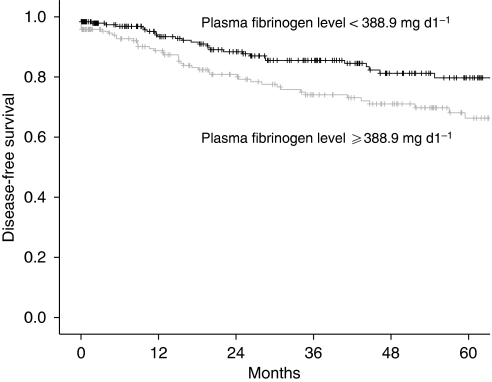

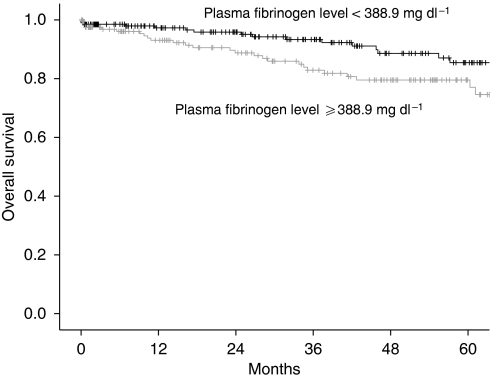

In a univariate analysis, tumour stage, histological grade, histological subtype, patients’ age, and pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels were associated with disease-free and overall survival. In a multivariate analysis, tumour stage, histological grade, patients’ age, and pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels were associated with disease-free and overall survival. Results of the univariate and multivariate Cox regression models and log-rank tests with respect to overall and disease-free survival are shown in Table 3. It is noteworthy that when patients were grouped according to the mean plasma fibrinogen level, patients with plasma fibrinogen levels of <388.9 and ⩾388.9 mg per 100 ml had a 5-year disease-free survival rate of 80 and 66% (P=0.01) and an overall survival rate of 84 and 74% (P=0.005), respectively (Figures 1 and 2). By comparing pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels between patients with and without recurrent disease in each FIGO tumour stage separately, we could show a significant difference within the group of FIGO tumour stage III and IV (P=0.03), but not within the group of FIGO tumour stage I (P=0.3) and II (P=0.5).

Table 3. Univariate and multivariate survival analysis.

|

Disease-free survival

|

Overall survival

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Univariate analysisa

|

Multivariate analysisb

|

Univariate analysisa

|

Multivariate analysisb

|

|||||

| P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | |

| Tumour stagec | <0.001 | — | <0.001 | 2.2 (1.7–2.8) | <0.001 | — | <0.001 | 2.1 (1.6–2.8) |

| Histological graded | <0.001 | — | 0.04 | 1.4 (1.02–2.0) | <0.001 | — | 0.002 | 1.8 (1.2–2.5) |

| Histological subtypee | <0.001 | — | 0.1 | 1.7 (0.9–3.4) | 0.002 | — | 0.6 | 1.3 (0.6–2.8) |

| Age | <0.001 | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | 0.001 | 1.04 (1.02–1.1) | <0.001 | 1.1 (1.0–1.1) | <0.001 | 1.1 (1.03–1.1) |

| Plasma fibrinogen levelsf | 0.002b | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.04 | 1.3 (1.01–1.6) | 0.001 | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 0.01 | 1.4 (1.1–1.2) |

Abbreviation: HR (95% CI)=hazard ratio (95% confidence interval).

Kaplan–Meier analysis.

Multivariate Cox regression model.

FIGO I vs FIGO II vs FIGO III and IV.

G1 vs G2 vs G3.

Endometrioid vs non-endometrioid histology.

Plasma fibrinogen levels per 100 units.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves for disease-free survival broken down by the mean plasma fibrinogen level.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival broken down by the mean plasma fibrinogen level.

Discussion

A strong association between haemostasis and tumour biology has been described previously (Dvorak, 1986; Von Tempelhoff et al, 2000; Balkwill and Mantovani, 2001; Coussens and Werb, 2002). In this retrospective multi-centre trial, we determined the effect of pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels on endometrial cancer in a large series of patients. By correlating pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels with clinical–pathological parameters, we could show a significant association between elevated plasma fibrinogen levels and advanced tumour stage.

These findings might be explained by hyperfibrinogenaemia induced by an inflammatory reaction to tumour growth and a hypercoagulable state in cancer patients (Gouin-Thibault et al, 2001; Coussens and Werb, 2002). Other studies describe the endogenous production of fibrinogen by tumour cells themselves (Lee et al, 1996; Lawrence and Simpson-Haidaris, 2004; Sahni et al, 2008). Fibrinogen and its degradation product fibrin seem to encase tumour cells and are capable of binding numerous cell types and growth factors, and exert an effect as a bridge between tumour and epithelial cells, thus providing structure to the tumour stroma and altering invasive potential (Dvorak et al, 1983; Dvorak, 1986; Costantini et al, 1991; Simpson-Haidaris and Rybarczyk, 2001). Through an interaction with fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibrinogen promotes angiogenesis and tumour cell growth (Sahni and Francis, 2000; Sahni et al, 2006, 2008). Another interesting research question would be to compare plasma fibrinogen levels before surgery, after surgery, during follow-up, and in an eventual recurrent disease situation. These questions cannot be answered by our present study, as only pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels were determined.

Not only tumour growth but also the metastatic potential of tumour cells seems to be influenced by fibrinogen, as could be showed in mice model studies (Palumbo et al, 2000, 2002, 2005). In our study, we could show a significant correlation between pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels and pre-treatment CA 125 levels. As CA 125 has been associated with lymphatic tumour cell spread in patients with endometrial cancer (Hsieh et al, 2002), our results seem to underline a possible functional link between fibrinogen and metastasis. Fibrinogen seems to stabilise tumour-associated platelets building microthrombi, which exert an effect as a physical barrier, preventing adherence of natural killer cells, monocytes, and lymphocytes to tumour cells. By protecting tumour cells against the innate immune system, fibrinogen enhances their metastatic potential (Palumbo et al, 2000, 2002, 2005; Biggerstaff et al, 2006, 2008).

The most interesting result of our study was the prognostic value of pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels regarding patients’ survival. The prognosis of patients with endometrial cancer is primarily determined by tumour stage, histological grade, histological subtype, and patients’ age (Creasman et al, 2001; Jolly et al, 2006; Fujimoto et al, 2009). Only limited data exist on prognostic serum tumour markers in patients with endometrial cancer, such as CA 125 and C-reactive protein (Dotters, 2000; Schmid et al, 2007). An association between blood rheology and prognosis in patients with gynaecological malignancy has previously been reported (Von Tempelhoff et al, 2000). Fibrinogen is associated with high plasma viscosity; it promotes aggregation of red blood cells and decreases cell deformability, resulting in reduced blood flow and oxygen transport capacity (Lowe, 1994). Low oxygenation of tumour tissue has been shown to be indicative of resistance to radiotherapy and poor prognosis on overall survival in cervical cancer (Hockel et al, 1996; Gundersen and Palmer, 2008).

One of the reviewers of this paper pointed us towards another unusual but interesting analysis. We compared pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels between non-recurrent and recurrent groups of patients in each FIGO tumour stage. A significant difference was only shown for patients with advanced stage, but not for early-stage disease. These findings are interesting, but do not change the conclusions of our study, as the multivariate Cox regression analysis confirmed the independence of the association between plasma fibrinogen levels and patients’ survival. Presumably in early FIGO tumour stages, the number of patients with recurrent disease is too small for showing a statistically significant difference.

Owing to early diagnosis of endometrial cancer, the overall prognosis of patients is relatively good compared with other gynaecological malignancies. Nevertheless, it is important to identify prognostic parameters in selecting patients for adjuvant therapy to avoid over-treatment. Along with pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels, the established prognostic parameters, namely, tumour stage, histological grade, and patients’ age, were found to be independently associated with survival. The majority of recurrence occurs within 36 months after diagnosis, which is covered by the follow-up time of the patients involved in our study (Fung-Kee-Fung et al, 2006).

In summary, our results show that plasma fibrinogen level is an independent prognostic parameter in patients with endometrial cancer. By showing a correlation between higher pre-treatment plasma fibrinogen levels and advanced tumour stage, we provide some insight into the possible functional properties of fibrinogen.

References

- Andreasen PA, Egelund R, Petersen HH (2000) The plasminogen activation system in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci 57: 25–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F, Mantovani A (2001) Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet 357: 539–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardos H, Molnar P, Csecsei G, Adany R (1996) Fibrin deposition in primary and metastatic human brain tumours. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 7: 536–548 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggerstaff JP, Weidow B, Dexheimer J, Warnes G, Vidosh J, Patel S, Newman M, Patel P (2008) Soluble fibrin inhibits lymphocyte adherence and cytotoxicity against tumor cells: implications for cancer metastasis and immunotherapy. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 14: 193–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biggerstaff JP, Weidow B, Vidosh J, Dexheimer J, Patel S, Patel P (2006) Soluble fibrin inhibits monocyte adherence and cytotoxicity against tumor cells: implications for cancer metastasis. Thromb J 4: 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown LF, Van de Water L, Harvey VS, Dvorak HF (1988) Fibrinogen influx and accumulation of cross-linked fibrin in healing wounds and in tumor stroma. Am J Pathol 130: 455–465 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauss A (1957) Rapid physiological coagulation method in determination of fibrinogen. Acta Haematol 17: 237–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantini V, Zacharski LR, Memoli VA, Kisiel W, Kudryk BJ, Rousseau SM (1991) Fibrinogen deposition without thrombin generation in primary human breast cancer tissue. Cancer Res 51: 349–353 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens LM, Werb Z (2002) Inflammation and cancer. Nature 420: 860–867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creasman WT, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Beller U, Benedet JL, Heintz AP, Ngan HY, Sideri M, Pecorelli S (2001) Carcinoma of the corpus uteri. J Epid Biostat 6: 47–86 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dotters DJ (2000) Preoperative CA 125 in endometrial cancer: is it useful? Am J Obstet Gynecol 182: 1328–1334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak HF (1986) Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N Engl J Med 315: 1650–1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorak HF, Senger DR, Dvorak AM (1983) Fibrin as a component of the tumor stroma: origins and biological significance. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2: 41–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto T, Nanjyo H, Fukada J, Nakamura A, Mizunuma H, Yaegashi N, Sugiyama T, Kurachi H, Sato A, Tanaka T (2009) Endometrioid uterine cancer: histopathological risk factors of local and distant recurrence. Gynecol Oncol 112: 342–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung-Kee-Fung M, Dodge J, Elit L, Lukka H, Chambers A, Oliver T, Cancer Care Ontario Program in Evidence-Based Care Gynecology Cancer Disease Site Group (2006) Follow-up after primary therapy for endometrial cancer: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol 101: 520–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouin-Thibault I, Achkar A, Samama MM (2001) The thrombophilic state in cancer patients. Acta Haematol 106: 33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen SI, Palmer AF (2008) Hemoglobin-based oxygen carrier enhanced tumor oxygenation: a novel strategy for cancer therapy. Biotechnol Prog 24: 1353–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantgan RR, Simpson-Haidiris PJ, Francis CW, Marder VJ (2001) Fibrinogen structure and physiology. In Haemostasis and Thrombosis: Basic Principles and Clinical Practice, Colman RW, Hirsh J, Marder VJ, Clowes AW, George JN (eds) 4th edn, pp 203–232. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh CH, ChangChien CC, Lin H, Huang EY, Huang CC, Lan KC, Chang SY (2002) Can a preoperative CA 125 level be a criterion for full pelvic lymphadenextomy in surgical staging of endometrial cancer? Gynecol Oncol 86(1): 28–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hockel M, Schlenger K, Aral B, Mitze M, Schaffer U, Vaupel P (1996) Association between tumor hypoxia and malignant progression in advanced cancer of the uterine cervix. Cancer Res 56: 4509–4515 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm B, Godal HC (1984) Quantitation of the three normally-occuring plasma fibrinogens in health and during so-called ‘acute-phase’ by SDS electrophoresis of fibrin obtained from EDTA-plasma. Thromb Res 35: 279–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly S, Vargas CE, Kumar T, Weiner SA, Brabbins DS, Chen PY, Floyd W, Martinez AA (2006) The impact of age on long-term outcome in patients with endometrial cancer treated with postoperative radiation. Gynecol Oncol 103: 87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM, McGonigle NC, McAnespie M, Cran GW, Graham AN (2006) Plasma fibrinogen and serum C-reactive protein are associated with non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 53: 97–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence SO, Simpson-Haidaris PJ (2004) Regulated de novo biosynthesis of fibrinogen in extrahepatic epithelial cells in response to inflammation. Thromb Haemost 92: 234–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Ryu KW, Kim S, Bae JM (2004) Preoperative plasma fibrinogen levels in gastric cancer patients correlate with extent of tumor. Hepatogastroenterology 51: 1860–1863 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SY, Lee KP, Lim JW (1996) Identification and biosynthesis of fibrinogen in human uterine cervix carcinoma cells. Thromb Haemost 75: 466–470 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe GD (1994) Rheological influences on thrombosis. Baill Clin Haematol 7: 573–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag S, Erickson B, Parikh S, Gupta N, Varia M, Glasgow G (2000) The American Brachytherapy Society recommendations for high-dose-rate brachytherapy for carcinoma of the endometrium. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 48: 779–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo JS, Kombrinck KW, Drew AF, Grimes TS, Kiser JH, Degen JL, Bugge TH (2000) Fibrinogen is an important determinant of the metastatic potential of circulating tumor cells. Blood 96: 3302–3309 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo JS, Potter JM, Kaplan LS, Talmage K, Jackson DG, Degen JL (2002) Spontaneous hematogenous and lymphatic metastasis, but not primary tumor growth or angiogenesis, is diminished in fibrinogen-deficient mice. Cancer Res 62: 6966–6972 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo JS, Talmage KE, Massari JV, La Jeunesse CM, Flick MJ, Kombrinck KW, Jirouskova M, Degen JL (2005) Platelets and fibrin(ogen) increase metastatic potential by impeding natural killer cell-mediated elimination of tumor cells. Blood 105: 178–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polterauer S, Seebacher V, Hefler-Frischmuth K, Grimm C, Heinze G, Tempfer C, Reinthaller A, Hefler L (2009) Fibrinogen plasma levels are an independent prognostic parameter in patients with cervical cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 200: 647.e1–647.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahni A, Francis CW (2000) Vascular endothelial growth factor binds to fibrinogen and fibrin and stimulates endothelial cell proliferation. Blood 96: 3772–3778 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahni A, Khorana AA, Baggs RB, Peng H, Francis CW (2006) FGF-2 binding to fibrin(ogen) is required for augmented angiogenesis. Blood 107: 126–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahni A, Simpson-Haidaris PJ, Sahni SK, Vaday GG, Francis CW (2008) Fibrinogen synthesized by cancer cells augments the proliferative effect of fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2). J Thromb Haemost 6: 176–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid M, Schneitter A, Hinterberger S, Seeber J, Reinthaller A, Hefler L (2007) Association of elevated C-reactive protein levels with an impaired prognosis in patients with surgically treated endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol 110: 1231–1236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson-Haidaris PJ, Rybarczyk B (2001) Tumors and fibrinogen. The role of fibrinogen as an extracellular matrix protein. Ann NY Acad Sci 936: 406–425 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi H, Ikeuchi S, Kitagawa Y, Shimada A, Oishi T, Isobe Y, Kubochi K, Kitajima M, Matsumoto S (2007) Pretreatment plasma fibrinogen level correlates with tumor progression and metastasis in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 22: 2222–2227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Tempelhoff GF, Nieman F, Heilmann L, Hommel G (2000) Association between blood rheology, thrombosis and cancer survival in patients with gynecologic malignancy. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 22: 107–130 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita H, Kitayama J, Kanno N, Yatomi Y, Nagawa H (2006) Hyperfibrinogenemia is associated with lymphatic as well as hematogenous metastasis and worse clinical outcome in T2 gastric cancer. BMC Cancer 6: 147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita H, Kitayama J, Nagawa H (2005) Hyperfibrinogenemia is a useful predictor for lymphatic metastasis in human gastric cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 35: 595–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]