Abstract

It has been shown that orexin plays an important role in the hypercapnic chemoreflex during wakefulness, and OX1Rs in the retrotrapezoid nucleus (RTN) participate in this mechanism. We hypothesized that OX1R in the rostral medullary raphe (MR) also contributes to the hypercapnic chemoreflex. We studied the effects on ventilation in air and in 7% CO2 of focal antagonism of OX1R in the rostral MR by microdialysis of SB-334867 in rats during wakefulness and NREM sleep, under dark and light periods. During wakefulness in the dark period, but not in the light period, SB-334867 caused a 16% reduction of the hyperventilation induced by 7% CO2 compared with vehicle. There was no significant effect in sleep. The basal ventilation, body temperature and V̇O2 were not affected. No effect was observed in a separate group of animals which had the microdialysis probe misplaced (peri-raphe). We conclude that OX1R in the the rostral medullary raphe contribute to the hypercapnic chemoreflex in wakefulness, during the dark period in rats.

1. INTRODUCTION

The orexin-containing neurons have been linked to the control of breathing, and there is a strong suggestion that these neurons are critical in the coordination between breathing and arousal states (Nakamura et al. 2007; Williams and Burdakov, 2008). The orexins, also known as hypocretins, include 2 subtypes of neuropeptides, the orexin-A and orexin-B (hypocretin-1 and hypocretin-2 respectively), which are derived from the same precursor (prepro-orexin), and bind to two G-protein coupled receptors: orexin receptor-1 (OX1R), selective for orexin-A, and orexin receptor-2 (OX2R), non-selective for both orexin-A and -B (de Lecea et al. 1998; Sakurai et al. 1998). The expression of orexin-containing neurons is restricted to the dorsal and lateral hypothalamus, but they have widespread projections to the whole brain (Peyron et al. 1998; Nambu et al. 1999), which explains the multiplicity of functions that are modulated by orexin, such as control of energy homeostasis, feeding behavior, reward processes, sleep-wake states, stress response, nociception, cardiovascular and respiratory control. Some evidence, indeed, supports the role of orexin on the control of breathing. Prepo-orexin knockout mice have a 50% attenuation of the hypercapnic chemoreflex during wakefulness, and this effect is partially restored with the administration of orexin-A and orexin-B (Deng et al. 2007; Nakamura et al. 2007). This is consistent with recent findings showing that orexin neurons are activated by pH and CO2 in vitro and in vivo (Williams et al. 2007; Sunanaga et al. 2009). Moreover, the intracerebroventricular injection of an OX1R-selective antagonist (SB-334867) decreased the respiratory chemoreflex by 24% in mice (Deng et al. 2007), and recently we have showed that the antagonism of OX1R in the RTN caused a 30% reduction of the ventilatory response to CO2 during wakefulness, and a 9% reduction during NREM sleep in rats (Dias et al. 2009).

Axonal processes immunoreactive to orexin have been demonstrated within the brainstem, including the medullary raphe (Nambu et al. 1999; Nixon and Smale, 2007). Similarly, OX1R expression was found in the medullary raphe nuclei (Hervieu et al. 2001; Marcus et al. 2001). Moreover, the administration of orexin in the fourth ventricle induces c-Fos expression in the raphe pallidus (Zheng et al. 2005). It is unknown, however, whether the OX1R in the medullary raphe contribute to hypercapnic chemoreflex.

We therefore investigate if OX1R in the rostral medullary raphe are involved with hypercapnic chemoreflex. We also asked if their role varies whether the animal is in the dark-active period or in the light-inactive period of the diurnal cycle. This question was due to the fact that there is a diurnal variation of the orexin-A levels in rat cerebrospinal fluid with higher values at the dark period, compared with the light period (Desarnaud et al. 2004). Thus, the role of orexin on control of breathing may be related to the diurnal cycle.

To address our questions, we submitted adult freely-moving rats to focal microdialysis of vehicle and then SB-334867 (OX1R antagonist) into the rostral medullary raphe to focally inhibit OX1R, and studied the effects of both treatments on breathing in room air and in 7% CO2 during wakefulness and NREM sleep, in the dark and light periods of the diurnal cycle.

2. METHODS

2.1. General

All animal experimentation and surgical protocols were within the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health for animal use and care and the American Physiological Society’s Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Dartmouth College Animal Resource Center. A total of 34 adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (250 to 350g) were used for the experiments and they were individually housed in a light- and temperature-controlled environment under a 12-h light: 12-h dark cycle, lights on at midnight for the dark period group, and at 7 AM for the light period group. The experiments were performed between 12 PM and 3 PM with the animals of the dark period group, and between 10 AM to 1PM with the animals of the light period group.

2.2. Surgery

Animals were submitted to general anesthesia by intramuscular administration of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (15 mg/kg). The head and a portion of the abdomen were shaved and the skin was sterilized with betadine solution and alcohol. Rats were fixed in a Kopf stereotaxic frame, and a dialysis guide cannula (CMA11, Microdialysis AB, Stockholm, Sweden) with a dummy was implanted into the rostral part of medullary raphe, which includes the raphe magnus and pallidus. The coordinates for probe placement were 2.5 mm caudal to lambda and 10.5 mm below the dorsal surface, in the midline (Paxinos and Watson, 1998). The guide cannula was secured with cranioplastic cement. Three EEG electrodes were screwed into the skull and a pair of EMG electrodes was inserted deep into the neck muscle. The skull wound was sutured. A sterile telemetry temperature probe (TA-F20, Data Sciences, St. Paul, MN) was placed in the abdominal cavity. The incision was closed, and the animal was allowed to recover for 7 days. The overall success rate for the probe placement was ~35%.

2.3. Microdialysis

The microdialysis probes used in this study had an 11 mm stainless-steel shaft, with a 1 mm long tip with a polyacrylonitrile membrane (0.34 mm o.d.), allowing diffusion of molecules under 5000 Da (Bioanalytical Systems, Inc, IN, USA) with no injection. Solutions were dialysed through the probe at a constant rate of 4 μl min−1 maintained by a syringe pump (KD 200, KD Scientific, Holliston, MA, USA). The OX1R antagonist SB-334867 (Tocris, Bristol, UK) was dissolved first in 4% DMSO and then the solution was diluted using 35% (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin in aCSF (artificial cerebrospinal fluid) to make 5 mM SB-334867. For the vehicle, we used a solution with 4% DMSO and 35% (2-hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin in aCSF. Dose and the method to dissolve the drug were chosen on the basis of previous studies (Deng et al. 2007).

2.4. Ventilation measurement

To measure ventilation in conscious rats, we used the whole-body plethysmograph technique as previously described (Bartlett and Tenney, 1970; Nattie and Li, 2002b; Dias et al. 2008). The animal chamber operates at atmospheric pressure, with the inflow gas humidified, and the flow rate controlled by a flowmeter (model 7491T, Matheson). The outflow port was connected to the in-house vacuum system via a flowmeter. A high-resistance “bleed” of the outflow line provided ~100 mL/min of outflow gas to the O2 and CO2 analyzers (Applied Electrochemistry). The flow rate through the plethysmograph was maintained at or above 1.4 L/min to prevent CO2 rebreathing. The plethysmograph was calibrated with 0.3-mL injections. The analog output of the pressure transducer was converted to a digital signal and directly sampled at 150 Hz by computer using the DataPac 2000 system. After the experiment, using the DATAPAC 2k2 software, breath events were individually selected and tidal volume (VT) and breathing frequency (fR) per breath were calculated to estimate ventilation (V̇E) per breath. Oxygen consumption (V̇O2) was calculated using the Fick principle using the difference in O2 content between inspired and expired gas and the flow rate through the plethysmograph and normalized to mL per gram body weight per hour.

2.5. Determination of Body Temperature

The chamber temperature was measured by a thermometer inside the chamber. Rat body temperature (Tb) was measured by using the analog output via telemetry from the temperature probe in the peritoneal cavity.

2.6. EEG and EMG signals

Arousal state was determined by analysis of EEG and EMG records as previously described (Nattie and Li, 2002a). The signals from the EEG and EMG electrodes were sampled at 150 Hz, filtered at 0.3–50 and 0.1–100 Hz, respectively, and recorded on the computer. Both wakefulness and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep states were observed consistently through the experiments but periods of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep were short and were not present in every experiment. Thus ventilation events that occurred during REM or when sleep state was indeterminate were excluded from our analysis.

2.7. Anatomic analysis

At the end of the experiment, the rats were killed with an overdose of sodium pentobarbitone injected intraperitoneally (> 75 mg/kg), the brainstems were frozen and then sectioned at 30-μm thickness with a Reichert-Jung cryostat. The sections were stained with cresyl violet. The distance between bregma and the probe tip (rostral–caudal level) was calculated by measuring the distance between the centre of the probe and the most caudal section showing the entire facial nerve (−10.04 mm relative to bregma; Paxinos and Watson, 1998). Animals that had probes falling in peripheral regions of the medullary raphe, were considered as a peri-raphe group.

2.8. Experimental Protocol

All experiments were performed at ambient temperature between 24 and 25°C. After insertion of the dialysis probe into the guide tube, the animals were placed into a plethysmograph chamber and allowed 40–60 min to acclimate. During this period the animals were dialysed with aCSF, without any measurement. Once the animals had acclimated, the dialysis solution was changed to the vehicle and the experimental recording began. Under room air conditions, ventilation, oxygen consumption, CO2 production and body temperature were measured every 5 min for 20–30 min, then the inspired air was switched to 7% CO2 balanced with air. Once the gas analyzer connected to the plethysmograph outflow reached 7% CO2, which took ~ 15 min, measurements were made each 5 min for a further 20–30 min. Thereafter, the same rats were allowed to rest in the chamber for at least 1 h under room air conditions with the plethysmograph top opened and with dialysis of aCSF. The dialysate was then changed to one with 5 mM SB-334867 and the protocol repeated. Each rat received only one dialysis probe insertion and 1 day of experimentation.

2.9. Statistics

For statistical analysis of ventilatory data, we used RM ANOVA with pre- and post-treatment V̇E, VT, and fR data as repeated measures with gas (room air versus hypercapnia) as categorical variables (SYSTAT Software Inc., Point Richmond, CA, USA). For the wake-sleep analysis we performed RM ANOVA with the awake and sleep percentages of time as repeated measures and group (raphe dark period; peri-raphe dark period; raphe light period) and gas (room air versus hypercapnia) as categorical variables. Post hoc test was carried out when appropriate via a modified Bonferroni approach.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Anatomy

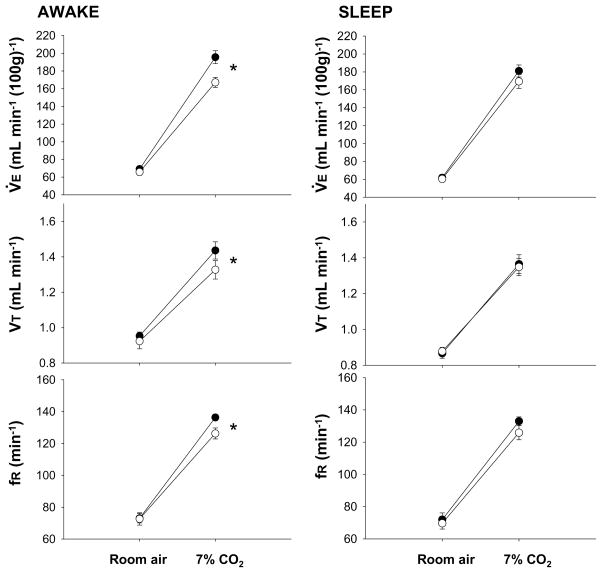

The cross sections of the medulla with the locations of the microdialysis probes tips are shown in the Fig. 1. Panels on the top show actual stained sections of a typical result of each group, for the probe placement. The six sections in Fig. 1(A) show the location of the tips of the probes in each rat in the dark period group. The mean distance from bregma for these 6 probes tips was −10.9 +/− 0.16 (SEM) mm with a range of −10.6 to −11.5 mm. Fig. 1(B) demonstrates the location of the probes tips of each rat in the light period group. The mean distance from bregma for these probes tips was −11.0 +/− 0.12 (SEM) mm with a range of −10.5 to −11.3 mm. Fig. 1(C) summarizes the locations for the peri-raphe group probes tips. As observed, the tips of the probes, in all 7 rats, were located outside of the raphe. The mean distance from bregma for these 7 probes was −10.9 +/− 0.09 (SEM) mm with a range of −10.6 to −11.2 mm.

Fig. 1.

Anatomic locations of the tips of the dialysis probes. Panels on the top are photomicrographs of stained coronal sections of the medulla of one representative rat of each group, showing the location of the tips of the probes. Scale bar: 1 mm. Schematized anatomic cross sections show locations of dialysis probes tips for animals receiving vehicle solution and SB-334867 in the medullary raphe during dark period (A), light period (B) and into the peri-raphe during dark period (C). Solid ovals show locations of raphe probes tips. The numbers below the cross sections refer to millimeters caudal to bregma. The drawings are modified from the atlas of Paxinos & Watson, 1998.

3.2. OX1R antagonist decreases the “CO2 response” in wakefulness, only during the dark period

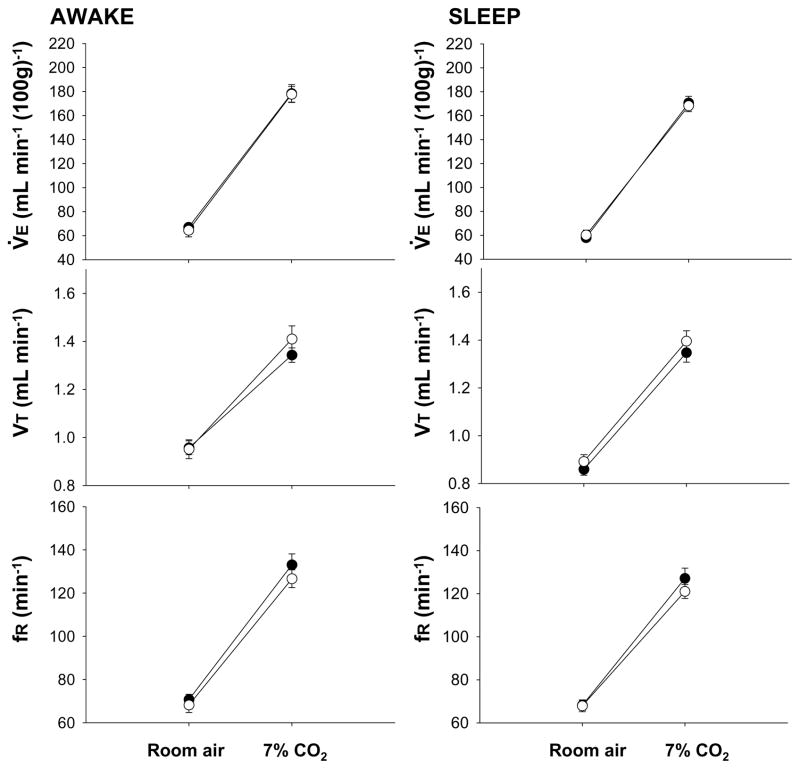

In Fig. 2 we show the effects of dialysis of 5mM SB-334867 into the medullary raphe on the ventilatory response to 7% CO2 during the dark period. We have chosen to express all the ventilatory data only as the absolute values, and not as V̇E/V̇O2 ratio for two reasons: (1) there was no statistical difference in the V̇O2 during the period of control solution dialysis compared with the OX1R antagonist dialysis. (2) The measurement of oxygen consumption is relatively slow due to the time it takes for wash-out of the plethysmograph as compared to ventilation, which is valid in a breath-by-breath manner. As a result, it is difficult to have the real value of V̇O2 for each sleep-awake state.

Fig. 2.

Effects of dialysis of vehicle solution (solid circles; N= 6) and 5 mM SB-334867 (open circles; N= 6) into the medullary raphe on V̇E, VT and fR while the rats were breathing air and 7% CO2 during wakefulness (left) and NREM sleep (right), in the dark period. Mean ± S.E.M. values are shown. * indicates values that are significantly different comparing pre- to post-treatment (vehicle to SB-334867 treatment) during 7% CO2 breathing for V̇E (P < 0.001, repeated measures ANOVA interaction with gas type), VT (P < 0.05, repeated measures ANOVA with no interaction with gas type), and fR (P < 0.05, repeated measures ANOVA interaction with gas type).

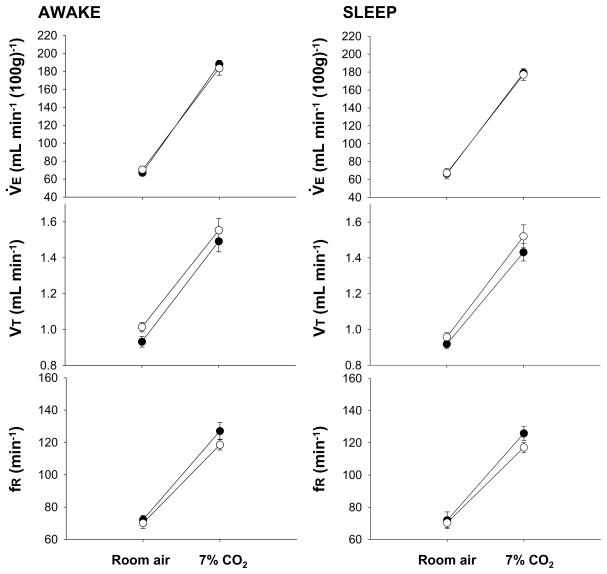

During the dark period, the dialysis of SB-334867 into the medullary raphe had no effect on air breathing values but caused a 16% reduction of V̇E during 7% CO2 breathing during wakefulness (P < 0.001; interaction of V̇E and Gas Type; P < 0.01, post hoc comparison). The effect was due to a significant attenuation in VT (P < 0.05; P < 0.01 post hoc comparison) and frequency (P < 0.05; interaction of fR, and Gas Type; P < 0.01 post hoc comparison). On the other hand, SB-334867 treatment caused no effect on ‘CO2 response’ in NREM sleep. Moreover, there was no difference between the CO2 response in the peri-raphe group in the dark period, during SB-334867 dialysis compared with the dialysis of control solution, neither in wakefulness nor in sleep (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effects of dialysis of vehicle solution (solid circles; N= 7) and 5 mM SB-334867 (open circles; N= 7) into the peri-raphe on V̇E, VT, and fR while the rats were breathing air and 7% CO2 during wakefulness (left) and NREM sleep (right), in the dark period. Mean ± S.E.M. values are shown.

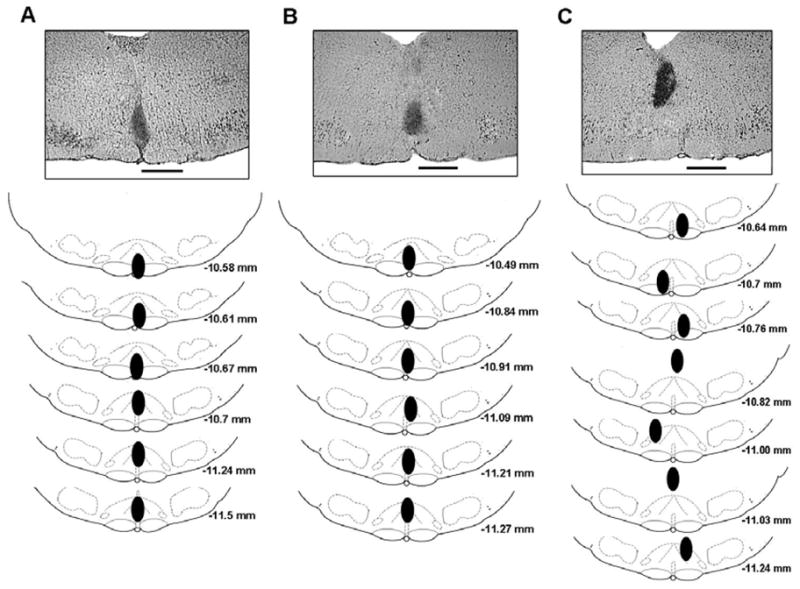

In Fig. 4 we show the effects of dialysis of 5mM SB-334867 into the medullary raphe on the ventilatory response to 7% CO2 during the light period. Different than in the dark period, the OX1R antagonism in the medullary raphe during the light period caused no significant change in the ventilatory respose to CO2 whether in wakefulness or sleep (P > 0.05 with gas type as the categorical variable).

Fig. 4.

Effects of dialysis of vehicle solution (solid circles; N= 6) and 5 mM SB-334867 (open circles; N= 6) into the medullary raphe on V̇E, VT and fR while the rats were breathing air and 7% CO2 during wakefulness (left) and NREM sleep (right), in the light period. Mean ± S.E.M. values are shown.

3.3. Body temperature and V̇O2

Our treatment with SB-334867 did not change the rat body temperature (p > 0.05; Student’s t-test) either in dark period or in light period. Oxygen consumption similarly did not vary significantly in response to the dialysis of SB-334867 (P > 0.05; Student’s t-test), but the V̇O2 in the dark period was significantly higher compared with the light period (P < 0.05; Student’s t-test).

3.4. Sleep-wakefulness

We obtained awake and NREM sleep times from the 20–30 minutes of room air and CO2 exposure periods. We asked if during this brief period, our treatment affected the time spent awake and in NREM sleep. Table 1 shows the percentage of the time the rats were awake during the experiments, in the raphe dark period, peri-raphe dark period and raphe light period groups. CO2 significantly increased the percentage of wakefulness in all data (p < 0.01; no interaction). Moreover, the treatment with SB-334867 significantly decreased the percentage of the time awake in all data (P < 0.02; no interaction). For the percentage of time in NREM sleep, CO2 significantly decreased it in all data (P < 0.01; no interaction). On the other hand, SB-334867 treatment did not significantly affect the percentage of NREM sleep in all groups (P = 0.06; no interaction).

Table 1.

Mean ± S.E.M values are shown.

Percent time spent in wakefulness and NREM sleep in air and 7% CO2 before and after the antagonism of OX1R by microdialysis of SB-334867 in the raphe dark period group (n = 6), peri-raphe dark period group (n = 7), and raphe light period group (n = 6).

| Raphe Dark period | Peri-Raphe Dark period | Raphe Light period | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | SB334867 | Control | SB334867 | Control | SB334867 | |||||||

| Air | 7%CO2 | Air | 7%CO2 | Air | 7%CO2 | Air | 7%CO2 | Air | 7%CO2 | Air | 7%CO2 | |

| AWAKE (%) | 39.5±9.1 | 54.8±13.1 | 29.9±7.8 | 51.5±2.8 | 31.7±4.5 | 62.7±10.9 | 21.3±3.3 | 46.8±9.6 | 30.6±7.7 | 60.6±8.5 | 17.4±3.8 | 51.9±4.6 |

| NREM SLEEP (%) | 57.8±8.6 | 43.6±12.1 | 58.1±4.9 | 48.5±2.7 | 58.8±4.2 | 33.4±8.7 | 62.3±6.0 | 44.6±7.0 | 67.3±6.7 | 39.4±8.5 | 82.5±3.6 | 48.2±4.6 |

4. DISCUSSION

We examined whether or not the dialysis of the OX1R antagonist SB-334867, in the area of the medullary raphe, has an effect in the hypercapnic chemoreflex in rats during the dark and light periods. We found that the ‘CO2 response’ was significantly attenuated by the antagonism of OX1R during wakefulness in the dark period, but not in the light period. This result supports our hypothesis that orexin receptor-1 (OX1R) in the rostral medullary raphe contributes to hypercapnic chemoreflex during wakefulness. Nevertheless this effect is dependent on the light-dark cycle.

As shown in Fig. 1, the dialysis probes tips were located within the rostral aspect of the medullary raphe to provide access to the neurons within the magnus and pallidus raphe nuclei. We did so because the medullary raphe appears to be heterogeneous in function related to chemoreception, particularly when we compare the rostral with the caudal aspect. It has been suggested that the rostral medullary raphe (raphe magnus and pallidus) may be a site of chemosensitivity that directly affects respiratory neurons while the caudal medullary raphe (raphe obscurus) acts as a modulator of other chemoreceptor sites (Nattie and Li, 2009). It has been demonstrated that medullary raphe receives projections from orexin-containing neurons (Nambu et al. 1999; Nixon and Smale, 2007). Also, the medullary raphe has been shown to express orexin receptors. OX1R and OX2R hybridization was seen in the rostral medullary raphe, while the caudal aspect of medullary raphe displayed only OX1R labeling. (Marcus et al. 2001). To date, however, the role of the orexin inputs in the medullary raphe has not been investigated. Recent studies have implicated the orexins in the neuronal regulation of the respiratory system (Peever et al. 2003; Young et al. 2005; Dutschmann et al. 2007). And of particular interest to us, orexin noticeably acts on the hypercapnic chemoreflex in a state-dependent manner. Accordingly, orexin knockout mice have attenuation of the ventilatory response to hypercapnia by 50% during wakefulness, but not during sleep (Deng et al. 2007; Nakamura et al. 2007), and the antagonism of OX1R in the RTN caused a 30% attenuation of ‘CO2 response’ in wakefulness, which was a much more prominent effect than during sleep (9% of reduction) (Dias et al. 2009). The state-dependent aspect of the role of orexins in the chemosensitivity is coherent with the growing evidence that orexin neurons are essential to promote and consolidate wakefulness (Gestreau et al. 2008). Indeed, the orexin system plays a key role in the control of vigilance and deficits in orexin neurotransmission can result in narcolepsy in animals and humans (Chemelli et al. 1999; Lin et al. 1999; Nishino et al. 2000). Orexin neurons provide excitatory inputs to the main nuclei involved with the control of arousal (Peyron et al. 1998; Nixon and Smale, 2007; Ohno and Sakurai, 2008). Moreover, the activity of orexin neurons is state-dependent. Direct recording of the neuronal activity of orexinergic neurons shows that the firing rate of these neurons is high during wakefulness and fall nearly silent in sleep (Lee et al. 2005; Mileykovskiy et al. 2005). Also, Estabrooke et al., (2001) demonstrated that c-Fos immunoreactivity in orexinergic cells in rats was elevated in wakefulness and reduced during NREM and REM sleep. As is true for the orexinergic neurons, the serotonergic neurons of medullary raphe also have a strong state dependence in firing rate, which is highest during active waking, reduced in NREM sleep and lowest in REM sleep (Heym et al., 1982). Further, it was demonstrated that the activity of medullary serotonergic neurons increases during motor activities, including during the hypercapnic challenge, and, interestingly, the responsiveness to hypercapnia of these neurons is reduced during sleep (Veasey et al., 1995).

Taken together, these data support the current notion that orexin system may play a key role in the chemosensitivity during wakefulness (Gestreau et al. 2008; Williams and Burdakov, 2008; Dias et al. 2009), which may be in part due to the orexinergic projections to the RTN (Dias et al. 2009), and to the medullary raphe. Accordingly, the results of the present study showed that the dialysis of 5 mM SB-334867 in the rostral medullary raphe caused a 16% reduction of the ventilatory response to CO2 during wakefulness, but not during sleep. It is noteworthy that this effect was observed just in the dark period, not in the light period. This finding is in accordance with previous studies showing that the extracellular levels of orexin vary across 24 hours, with higher levels in the dark period (active phase) compared with the light period (inactive phase) (Yoshida et al. 2001; Desarnaud et al. 2004). In fact, the oral administration of an antagonist of OX1R and OX2R caused a decreased alertness and increased NREM and REM sleep in rats, dogs and humans, but this effect was observed only during the active period of the circadian cycle. When the drug was given at the inactive period, there was no effect on activity and alertness, in contrast to the active period treatment (Brisbare-Roch et al. 2007). The orexinergic neurons may thus play a key role in the hypercapnic chemoreflex not only in a state-dependent manner, but also, in a period-dependent manner. Thus, the orexin-mediated changes in chemosensitivity may be more prominent at the onset of the active period when the release of orexin is greater.

An earlier study about chemoreception in the rostral medullary raphe showed that the focal acidification of this region using 25% CO2 dialysis increased ventilation only in sleep (Nattie and Li, 2001). The nature of the discrepancy between that report and our current results may be due to the fact that the CO2 dialysis in that study was done during the last part of the light period, when the orexin-1 in the cerebrospinal fluid is at its lowest level. In other words, when the orexin neurons are more active (during wakefulness in the dark period in rats) they enable the raphe to respond to CO2, but during sleep and in the light period other mechanisms may account for chemoreception in the raphe.

In the RTN, the focal antagonism of OX1R caused a 30% attenuation of ‘CO2 response’ in wakefulness (Dias et al. 2009). This effect was two fold greater than that observed in the rostral medullary raphe. This observation suggests that OX1R in the RTN may have a prominent role in the ventilatory responses to the hypercapnic chemoreflex in wakefulness, compared to the rostral medullary raphe. However, more studies are necessary to investigate the relative importance of these regions in the orexin-mediated changes in chemosensitivity. The influence of the raphe alone may be smaller than the RTN alone but previous studies (Li et al. 2006; Dias et al. 2008) indicate an interaction between caudal medullary raphe and RTN so if there is a similar interaction between the rostral aspect of medullary raphe and the RTN, we might expect a similar interaction with OX1R antagonism. It is important to point out that as orexinergic neurons innervate not only the RTN and the medullary raphe, but also other respiration-related sites, as the nucleus tractus solitarius, pre-Bötzinger complex, locus coeruleus, and spinal cord (Nambu et al. 1999; Nixon and Smale, 2007), we could assume that breathing stimulation by orexin results from an effect at multiple levels of neuroaxis.

The treatment with SB-334867 in the rostral medullary raphe did not change the ventilation in air breathing, as we previously found with the dialysis of SB-334867 into the RTN (Dias et al. 2009). Likewise, Deng et al (2007) found that the icv administration of SB-334867 did not influence spontaneous ventilation in mice, whether in wakefulness, or in sleep. Moreover, orexin knockout mice do not have an alteration in the basal breathing (Deng et al. 2007). These data suggest that the orexin system may not participate in the control of breathing under normocapnic condition. This hypothesis is congruent with the notion that orexinergic neurons mediate cardiorespiratory responses to stress, including breathing stimulation (Kayaba et al., 2003; Zhang et al., 2006; Kuwaki et al., 2008). The orexin system could therefore contribute to the stress induced responses to CO2, during wakefulness, but under normal conditions without any stressors, it may not affect the baseline breathing.

In this study, we limited the exposure to 7% CO2 to ~25 min, a period that minimized time-dependent brain pH regulatory processes but still allowed study of responses in wakefulness and NREM sleep. However, this protocol is not well suited to evaluate fully the characteristics of wakefulness and NREM sleep because priority was set on observing the hypercapnic chemoreflex rather than on vigilance states. However, even in our brief experimental period, we could see an arousal effect of CO2, and a tendency of SB-334867 treatment to lessen wakefulness, independent of probe location or dark–light period differences. This could reflect a wider distribution of OX1R that affect arousal than the CO2 response. However, due to our protocol design, it is possible that the tendency of animals to have lesser time of wakefulness may be caused by the time course, since the treatment with SB-334867 affected all groups, including the control group (peri-raphe).

The dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH), one of the hypothalamic regions where the orexinergic neurons are located, has been implicated in the thermogenic sympathetic outflow, and the pallidus raphe seems to mediate this effect (DiMicco and Zaretzky 2007; Morrison et al., 2008). However, in our study there was no change in the body temperature with the OX1R antagonism in the rostral medullary raphe.

In summary, our results support the recent notion regarding the orexinergic system as part of the state-dependent control of breathing, and bring forth a new concept: the orexinergic neurotransmission in the medullary raphe, via OX1R may be an important mechanism that operates to modulate breathing during activation of the hypercapnic chemoreflex under wakefulness during the active phase of the diurnal cycle.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jessica Dong for helpful technical assistance. This work was supported by a grant from the NHLBI, R37 HL 28066.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bartlett D, Jr, Tenney SM. Control of breathing in experimental anemia. Respir Physiol. 1970;10:384–395. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(70)90056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brisbare-Roch C, Dingemanse J, Koberstein R, Hoever P, Aissaoui H, Flores S, Mueller C, Nayler O, van Gerven J, de Haas SL, Hess P, Qiu C, Buchmann S, Scherz M, Weller T, Fischli W, Clozel M, Jenck F. Promotion of sleep by targeting the orexin system in rats, dogs and humans. Nat Med. 2007;13:150–155. doi: 10.1038/nm1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chemelli RM, Willie JT, Sinton CM, Elmquist JK, Scammell T, Lee C, Richardson JA, Williams SC, Xiong Y, Kisanuki Y, Fitch TE, Nakazato M, Hammer RE, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M. Narcolepsy in orexin knockout mice: molecular genetics of sleep regulation. Cell. 1999;98:437–451. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lecea L, Kilduff TS, Peyron C, Gao X, Foye PE, Danielson PE, Fukuhara C, Battenberg EL, Gautvik VT, Bartlett FS, 2nd, Frankel WN, van den Pol AN, Bloom FE, Gautvik KM, Sutcliffe JG. The hypocretins: hypothalamus-specific peptides with neuroexcitatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:322–327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng BS, Nakamura A, Zhang W, Yanagisawa M, Fukuda Y, Kuwaki T. Contribution of orexin in hypercapnic chemoreflex: evidence from genetic and pharmacological disruption and supplementation studies in mice. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1772–1779. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00075.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desarnaud F, Murillo-Rodriguez E, Lin L, Xu M, Gerashchenko D, Shiromani SN, Nishino S, Mignot E, Shiromani PJ. The diurnal rhythm of hypocretin in young and old F344 rats. Sleep. 2004;27:851–856. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.5.851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias MB, Li A, Nattie E. Focal CO2 dialysis in raphe obscurus does not stimulate ventilation but enhances the response to focal CO2 dialysis in the retrotrapezoid nucleus. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:83–90. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00120.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias MB, Li A, Nattie EE. Antagonism of orexin receptor-1 in the retrotrapezoid nucleus inhibits the ventilatory response to hypercapnia predominantly in wakefulness. J Physiol. 2009;587:2059–2067. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.168260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimicco JA, Zaretsky DV. The dorsomedial hypothalamus: a new player in thermoregulation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R47–63. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00498.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutschmann M, Kron M, Morschel M, Gestreau C. Activation of Orexin B receptors in the pontine Kolliker-Fuse nucleus modulates pre-inspiratory hypoglossal motor activity in rat. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2007;159:232–235. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estabrooke IV, McCarthy MT, Ko E, Chou TC, Chemelli RM, Yanagisawa M, Saper CB, Scammell TE. Fos expression in orexin neurons varies with behavioral state. J Neurosci. 2001;21:1656–1662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-05-01656.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gestreau C, Bevengut M, Dutschmann M. The dual role of the orexin/hypocretin system in modulating wakefulness and respiratory drive. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2008;14:512–518. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32831311d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervieu GJ, Cluderay JE, Harrison DC, Roberts JC, Leslie RA. Gene expression and protein distribution of the orexin-1 receptor in the rat brain and spinal cord. Neuroscience. 2001;103:777–797. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heym J, Steinfels GF, Jacobs BL. Activity of serotonin-containing neurons in the nucleus raphe pallidus of freely moving cats. Brain Res. 1982;251:259–276. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90743-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayaba Y, Nakamura A, Kasuya Y, Ohuchi T, Yanagisawa M, Komuro I, Fukuda Y, Kuwaki T. Attenuated defense response and low basal blood pressure in orexin knockout mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R581–593. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00671.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwaki T, Zhang W, Nakamura A, Deng BS. Emotional and state-dependent modification of cardiorespiratory function: role of orexinergic neurons. Auton Neurosci. 2008;142:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MG, Hassani OK, Jones BE. Discharge of identified orexin/hypocretin neurons across the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6716–6720. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1887-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Zhou S, Nattie E. Simultaneous inhibition of caudal medullary raphe and retrotrapezoid nucleus decreases breathing and the CO2 response in conscious rats. J Physiol. 2006;577:307–318. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.114504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin L, Faraco J, Li R, Kadotani H, Rogers W, Lin X, Qiu X, de Jong PJ, Nishino S, Mignot E. The sleep disorder canine narcolepsy is caused by a mutation in the hypocretin (orexin) receptor 2 gene. Cell. 1999;98:365–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81965-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus JN, Aschkenasi CJ, Lee CE, Chemelli RM, Saper CB, Yanagisawa M, Elmquist JK. Differential expression of orexin receptors 1 and 2 in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 2001;435:6–25. doi: 10.1002/cne.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mileykovskiy BY, Kiyashchenko LI, Siegel JM. Behavioral correlates of activity in identified hypocretin/orexin neurons. Neuron. 2005;46:787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SF, Nakamura K, Madden CJ. Central control of thermogenesis in mammals. Exp Physiol. 2008;93:773–797. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.041848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, Zhang W, Yanagisawa M, Fukuda Y, Kuwaki T. Vigilance state-dependent attenuation of hypercapnic chemoreflex and exaggerated sleep apnea in orexin knockout mice. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:241–248. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00679.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambu T, Sakurai T, Mizukami K, Hosoya Y, Yanagisawa M, Goto K. Distribution of orexin neurons in the adult rat brain. Brain Res. 1999;827:243–260. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01336-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattie E, Li A. Central chemoreception is a complex system function that involves multiple brain stem sites. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1464–1466. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00112.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattie EE, Li A. CO2 dialysis in the medullary raphe of the rat increases ventilation in sleep. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:1247–1257. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.4.1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattie EE, Li A. CO2 dialysis in nucleus tractus solitarius region of rat increases ventilation in sleep and wakefulness. J Appl Physiol. 2002a;92:2119–2130. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01128.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nattie EE, Li A. Substance P-saporin lesion of neurons with NK1 receptors in one chemoreceptor site in rats decreases ventilation and chemosensitivity. J Physiol. 2002b;544:603–616. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.020032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino S, Ripley B, Overeem S, Lammers GJ, Mignot E. Hypocretin (orexin) deficiency in human narcolepsy. Lancet. 2000;355:39–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05582-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon JP, Smale L. A comparative analysis of the distribution of immunoreactive orexin A and B in the brains of nocturnal and diurnal rodents. Behav Brain Funct. 2007;3:28. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-3-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K, Sakurai T. Orexin neuronal circuitry: role in the regulation of sleep and wakefulness. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2008;29:70–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. Academic press; New York: 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peever JH, Lai YY, Siegel JM. Excitatory effects of hypocretin-1 (orexin-A) in the trigeminal motor nucleus are reversed by NMDA antagonism. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:2591–2600. doi: 10.1152/jn.00968.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG, Kilduff TS. Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9996–10015. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09996.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H, Williams SC, Richardson JA, Kozlowski GP, Wilson S, Arch JR, Buckingham RE, Haynes AC, Carr SA, Annan RS, McNulty DE, Liu WS, Terrett JA, Elshourbagy NA, Bergsma DJ, Yanagisawa M. Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell. 1998;92:573–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80949-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunanaga J, Deng BS, Zhang W, Kanmura Y, Kuwaki T. CO2 activates orexin-containing neurons in mice. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;166:184–186. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veasey SC, Fornal CA, Metzler CW, Jacobs BL. Response of serotonergic caudal raphe neurons in relation to specific motor activities in freely moving cats. J Neurosci. 1995;15:5346–5359. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-05346.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RH, Burdakov D. Hypothalamic orexins/hypocretins as regulators of breathing. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2008;10:e28. doi: 10.1017/S1462399408000823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RH, Jensen LT, Verkhratsky A, Fugger L, Burdakov D. Control of hypothalamic orexin neurons by acid and CO2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10685–10690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702676104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida Y, Fujiki N, Nakajima T, Ripley B, Matsumura H, Yoneda H, Mignot E, Nishino S. Fluctuation of extracellular hypocretin-1 (orexin A) levels in the rat in relation to the light-dark cycle and sleep-wake activities. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1075–1081. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JK, Wu M, Manaye KF, Kc P, Allard JS, Mack SO, Haxhiu MA. Orexin stimulates breathing via medullary and spinal pathways. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1387–1395. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00914.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Shimoyama M, Fukuda Y, Kuwaki T. Multiple components of the defense response depend on orexin: evidence from orexin knockout mice and orexin neuron-ablated mice. Auton Neurosci. 2006;126–127:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Patterson LM, Berthoud HR. Orexin-A projections to the caudal medulla and orexin-induced c-Fos expression, food intake, and autonomic function. J Comp Neurol. 2005;485:127–142. doi: 10.1002/cne.20515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]