Abstract

Virtual Environments (VEs) that use a real-walking locomotion interface have typically been restricted in size to the area of the tracked lab space. Techniques proposed to lift this size constraint, enabling real walking in VEs that are larger than the tracked lab space, all require reorientation techniques (ROTs) in the worst-case situation–when a user is close to walking out of the tracked space. We propose a new ROT using visual and audial distractors–objects in the VE that the user focuses on while the VE rotates–and compare our method to current ROTs through three user studies. ROTs using distractors were preferred and ranked more natural by users. Users were also less aware of the rotating VE when ROTs with distractors were used. Our findings also suggest that improving visual realism and adding sound increased a user's feeling of presence.

Index Terms: Virtual Environments, Walking, Locomotion, User Studies, Reorientation Techniques

1 Introduction

Real walking in Virtual Environments (VEs) is more natural and produces a higher sense of presence than other locomotion techniques, such as walking-in-place and joystick interfaces [1], [2]. Omni-directional treadmills do not enable real-walking since users must “readapt” to real motion after extensive training [3]. However, VEs using a real-walking locomotion interface have typically been restricted in size to the area of the tracked lab space. Techniques have been proposed to lift this size constraint, enabling real walking in VEs that are larger than the tracked space [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. Each of these large-area walking VE methods relies on a reorientation technique (ROT) to handle the case when the technique fails and the user is close to walking out of the tracked space. When such an event happens, ROTs must stop the user and rotate the VE around her current virtual location, placing the immediately expected user path back within the tracked space. The user must also reorient herself by turning around in the real environment so she can follow her desired path in the newly-rotated VE.

ROTs are required to enable free exploration of large VEs without the use of joysticks, walking-in-place interfaces, treadmills, or bicycles [11], [12], [3], [13], [14]. We want to provide users with the most physically accurate VE experience possible. We hypothesize that current ROT implementations cause breaks in presence, which detract from the immersive VE experience. In this paper we introduce a new ROT and compare our method to existing ROTs through three user studies. We evaluate each ROT based on presence, user-ranked preference, and user-ranked naturalness.

Our method introduces the concept of a distractor–an object, sound, or combination of object and sound in the VE that the user focuses on while the VE rotates, reducing perception of the rotation, and thus reducing the likelihood of a break in presence. In the three studies we compare our new distracter technique to previously reported techniques. The first two studies were presented in [15]. The methods introduced by Razzaque [5], [6], [7] and Williams [9], [10] induce the user reorientation via audio instructions, rotating the VE while the user is following the instructions. Nitzsche and Su rotate the VE without warning or additional instructions [4], [8].

2 Background

Three real-walking techniques exist for exploring large immersive VEs and each method suggests its own ROT to enable free exploration. Redirected walking [5], [6], [7] is a technique that exploits the imprecision of human perception of self-motion–the motion of humans based on sensory cues–and modifies the direction of the users gaze by imperceptibly rotating the VE around the user. The primary design goal of this technique is that it be imperceptible to the user. Razzaque suggests a ROT with a loudspeaker in the VE that asks the user to stop, turn her head back and forth, and continue walking in the same direction. Razzaque determined that a user is least likely to notice extra rotation while she is turning her head because of the imprecision of human self-motion perception. Redirected walking rotates the VE during such moments, moving the user's path so that it falls within the tracked environment.

Motion compression [4], [8] rotates the VE such that the predicted user path is the largest possible arc that can fit into the tracked lab space and, like redirected walking, continuously updates the location and the rotation of the VE relative to the lab space. Unlike redirected walking, motion compression does not make imperceptibility of rotation a primary goal. The ROT used in motion compression is built into the motion compression algorithm: as the user approaches the edge of the tracked space, the VE rotates the predicted user path into the tracked area without warning (following the computed arc of minimum curvature) causing the user to feel that the VE is spinning around.

Scaled translational gain [9], [10] increases the translational step size of the user in the VE, without modifying rotation by scaling the output of the tracker. Interrante et al. [16] scale the step-size of the user. Williams et al. explored three “resetting” methods for manipulating the VE when the user nears the edge of the tracked space [17]. The “resetting” techniques attempt to interfere with virtual experience as minimally as possible. One technique involves turning the HMD off, instructing the user to walk backwards to the middle of the lab, and then turning the HMD back on. The user will then find herself in the same place in the VE but will no longer be near the edge of the tracked space. The second technique turns the HMD off, asks the user to turn in place, and then turns the HMD back on. The user will then find herself facing the same direction in the VE, but facing a different direction in the tracked space. Preliminary research [17] suggests that the most promising of the three techniques uses an audio warning to ask the user to stop and turn 360°. The VE rotates at twice the speed of the user and stops rotating after 180°. The user is supposed to reorient herself by turning only 180° but should think she has turned 360°. This ROT attempts to trick the user into not noticing the extra rotation.

Current techniques have characteristics that we believe are likely to cause breaks in presence: audio instructions (unrelated to the content of the VE) and unexpected large rotations of the VE. Our method differs from the current methods in that it does not unexpectedly rotate the VE or use unnatural audio cues. We distract the user with a moving audial, visual, or audial and visual object in the VE. While the user is rotating her head to follow the distractor, the VE is rotated around her. This is similar to a method implemented by Kohli [18], and exploits the imprecision of vestibular perception suggested by Razzaque [7]. We hypothesize that the visual distraction will make the rotation of the VE less noticeable to the user and will not detract from the immersive virtual experience. We conducted a user study to evaluate our method and compare it to the ROTs suggested by Razzaque, Williams, and Nitzsche. Based on the results, we improved our distractor and conducted two follow on studies to evaluate our improved distractors against the most promising ROT's determined by previous evaluation.

3 Methods

We conducted three University of North Carolina IRB approved within-subjects user studies to evaluate ROTs and compare distractors to current ROTs. Subjects were different between all experiments. Experiment 1 showed that of the current ROTs, users preferred our method as well as the method suggested by Razzaque [7]. We modified our distractor technique based on user feedback from the first study and then conducted a follow-on study comparing the improved distractor ROT to our original method and to the method suggested by Razzaque [7]. The third study explored improving the visual quality of the distractor as well as adding natural audio to a visual distractor and using audio alone as a distractor.

3.1 Equipment

Each participant wore a Virtual Research Systems V8 head-mounted display (640 × 480 resolution) tracked using a 3rdTech HiBall 3000. Participants were permitted to walk in an 8m × 6m tracked space. The environment used in experiments 2 and 3 is shown in Figure 1. A similar environment was used in experiment 1. All environments were rendered in stereo at 60 fps on a Pentium D dual-core 2.8GHz processor machine with an NVIDIA GeForce 6800 GPU with 2GB of RAM. The cardboard taped to the wooden surface was slightly padded and gave users, who had no self-avatar, haptic confirmation of reaching the markers on the paths.

Fig. 1.

Virtual Environment used in Experiment 2 and 3.

3.2 Experiment 1

Our first study evaluated the ROTs suggested or implemented by [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [17] plus our distractor technique. The measures were presence, user-ranked preference, and user-ranked naturalness.

3.2.1 Participants

Twenty-four introductory psychology students (13 men and 11 women) participated in the experiment. Each subject visited the laboratory once for a session lasting approximately 1 hour and received class credit for participation. All subjects had normal or corrected to normal vision and were naive to the purpose of the study. Participants were not informed about ROTs and were initially unaware that the VE would rotate.

3.2.2 Experimental Design

Experiment 1 consisted of two parts, both taking place in the same VE. The VE was an outdoor space featuring a 200-meter straight wooden path with circular markers placed 5 meters apart along the path. The virtual environment was similar to the environment used in experiment 2, shown in Figure 1. To walk the virtual path, subjects really walked 5 meters across the lab to a marker, turned 180° and walked back across the lab to the next marker. The rotation of the VE occurred only during reorientation. Subjects received audio instructions, via head phones, before the experiment began and received audio trial-specific instructions, via head phones, before each trial. Trial specific instructions included informing subjects to physically turn, turn your head back and forth, or watch the distractor. Subjects did not have a training session and no subject had problems performing the experiment. Subjects were instructed to walk along the path in the environment and to stop at each marker. Once a subject reached a marker, the subject experienced one of four reorientation techniques.

Turn without instruction (T)

When the user reaches the marker the VE immediately rotates 180° around the user at 120°/second. The rotation relocates the virtual path so it is located within the tracked environment. The user needs to reorient herself in the VE by turning 180°. This is similar to the technique described in [4], [8].

Turn with audio instruction (TI)

Audio instructions in the VE, presented via headphones, ask the user to turn 360° and continue along the path; however, the VE rotates 180°. The rotation of the VE is controlled by the user's head and rotates at twice the speed of the user's head. The user is deceived to think that she has turned 360° in both the virtual and real worlds when she has only turned 180° in the real world. The user needs to reorient herself in the VE by turning only 180°. This is similar to a method described in [17].

Head turn with audio instruction (HT)

Audio instructions in the VE, presented via headphones, ask the user to turn her head back and forth and then continue walking along the path. While the user turns her head the rotation applied to the VE is 1.3 times the rotation speed of the user's head until the VE has rotated 180°. The participant reorients herself by rotating 180° in the real world. This is similar to a method described in [7].

Head turn with visual instruction, distractor (D)

A moving sphere appears in front of the user. The user watches the sphere as it moves in a horizontal arc and continues walking along the path once the sphere disappears. The rotation applied to the VE is 1.5 times the rotation speed of the user's head until the VE has rotated 180°. The distractor moves along the arc with sinusoidal displacement, amplitude = 0.5 meters and frequency = 8°/second. The user reorients herself by rotating 180° in the real world. The path and velocity of the distractor are described in Figure 3.

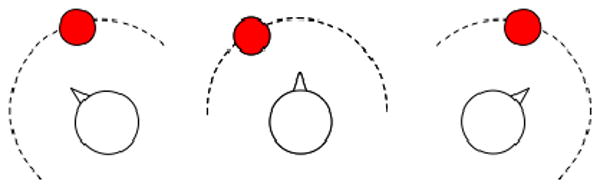

Fig. 3.

The path of all distractors is defined as an arc (dashed line) directly in front of the user with sinusoidal displacement along the arc. The distractor moves along the arc causing the subject to turn her head back and forth to keep the distractor in view. The distractor is displayed 1.75 meters away from the user, and the height of all distractors is approximately 0.5 meters. The same path trajectory is used for all distractors in each of the three experiments.

All rotation rates were determined from pilot experiments. For all reorientation techniques the rotation of the virtual environment is increased only when the direction the head is turning in the same direction the VE is rotating.

Part I of the experiment assessed the user's subjective sense of presence in the environment and consisted of four trials, each using one of the four reorientation techniques. The order of the trials was counterbalanced among subjects. Each trial was comprised of four sub-trials in which the subject walked along the virtual path and stopped at markers along the path. When the subject reached a marker, an ROT would stop the subject and rotate the VE. Each trial consisted of walking to four markers and experiencing the same reorientation technique four times. Subjects then removed the HMD and filled out a modified Slater-Usoh-Steed (SUS) presence questionnaire [19], [20].

Part II consisted of 12 trials, each with two reorientation techniques. Trials were counterbalanced and every ROT was compared to every other ROT twice, with order reversed, to remove the possibility of order effects. Each trial required the subject to walk to a marker, experience an ROT, then walk to the next marker, and experience a different ROT. The subject then made a forced choice regarding which ROT they preferred and which ROT was most natural. At the end of each trial subjects were asked by the experimenter to explain why they chose one ROT over another.

At the end of the experiment subjects filled out an exit survey and were asked to describe the differences between the four ROTs, explain what they liked or disliked about each of the ROTs, and rank the four ROTs based on naturalness and preference.

We used a modified SUS presence questionnaire [19], [20] to assess the user's subjective sense of presence. Naturalness and preference were each measured in two ways: at the end of the experiment subjects ranked the ROTs, and during the experiment subjects made a forced-choice ranking between pairs of ROTs.

3.2.3 Results

Tables 1 and 2 and Figures 4 through 8 show our results from Experiment 1. The SUS presence scores were analyzed using the same binomial logistic regression techniques as applied in previous uses of the questionnaire [1]. The response to each question was converted from the 1 to 7 scale to a binary value: responses of 5, 6, or 7 were converted to HIGH (1) and values less than 5 were converted to LOW (0). This conversion avoids treating the subjective ratings as interval data. After this conversion, we further transformed the data to create a new response variable for each participant: the count of their HIGH responses. Tables 1 and 2 show the average proportion of HIGH responses for each of the four conditions as well as the pairwise contrasts of conditions using logistic regression adjusted for multiple observations for each participant. There is a statistically significant effect between HT vs. TI (χ2(1) = 11.97, p < 0.05) and T vs. TI (χ2(1) = 6.39, p < 0.05). We also found a trend between D vs. TI (χ2(1) = 3.35, p = 0.0672).

TABLE 1.

Experiment 1 - Mean HIGH scores on SUS Presence Questionnaire

| ROT | x̄ |

|---|---|

| D | 0.47917 |

| HT | 0.50000 |

| TI | 0.28472 |

| T | 0.44444 |

TABLE 2.

Experiment 1 - Results of Logistic Regression of SUS Presence Questionnaire. Statistically significant results are marked with a box.

| Contrast | χ2(1) | p(α = 0.05) |

|---|---|---|

| D vs. HT | 0.15 | 0.6980 |

| D vs. TI | 3.35 | 0.0672 |

| D vs. T | 0.02 | 0.8912 |

| HT vs. TI | 11.97 | 0.0005 |

| HT vs. T | 0.46 | 0.4986 |

| T vs. TI | 6.39 | 0.0115 |

Fig. 4.

Experiment 1–Legend

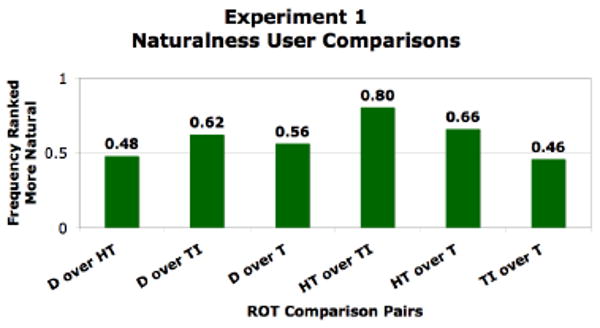

Fig. 8.

Experiment 1–User forced-choice comparisons of naturalness across ROTs.

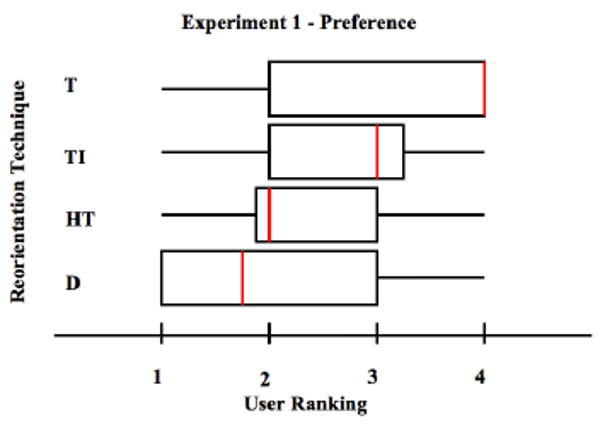

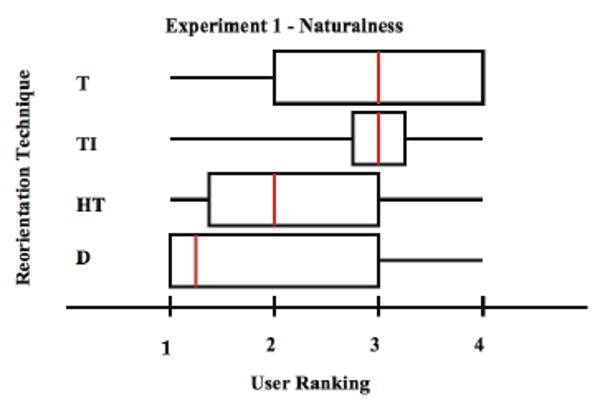

Figures 5 and 6 show the average user rankings, with 1 being the higest and 4 being the lowest, of preference and naturalness by ROT respectively. The data was analysed using Friedman's ANOVA. User-ranked naturalness was significantly different between ROTs: χ2(3) = 9.524, p < 0.05, as was user-ranked preference (χ2(3) = 10.958, p < 0.01). Wilcoxon tests were used to expand on this finding and a Bonferroni correction was applied. All effects are reported at a 0.0125 level of significance. The Wilcoxon test statistic is T′ and should not be confused with our condition T. Subjects significantly found HT to be more natural than TI, (T′ = 220.00, r = 0.38) and significantly preferred D and HT to T, T′ = 237.50, r = 0.37 and T′ = 235.50, r = 0.36 respectively.

Fig. 5.

Experiment 1–User rated preference scores from 1 (most preferred) to 4 (least preferred). Standard box-and-whisker plots with the median in red.

Fig. 6.

Experiment 1–User rated naturalness scores from 1 (most natural) to 4 (least natural). Standard box-and-whisker plots with the median in red.

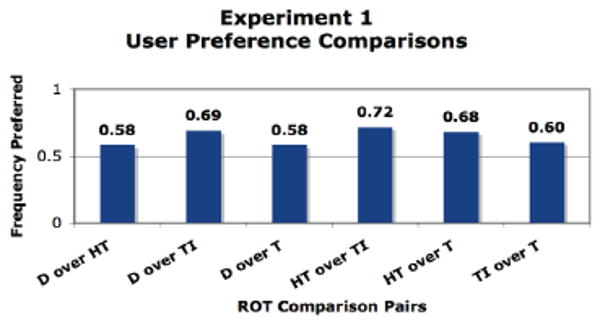

Figures 7 and 8 show user preference and user-ranked naturalness of paired ROTs. The frequency at which a subject preferred one ROT over another was compared to random choice, a frequency of 0.50, using Wilcoxon tests. We found subjects significantly preferred D over TI (T′ = 184.00, p < 0.05, r = 0.31), HT over TI (T′ = 176.00, p < 0.05, r = 0.35), and HT over T (T′ = 165, p < 0.5, r = 0.28) and subjects significantly considered HT to be more natural than TI, (T′ = 170.00, p < 0.01, r = 0.50).

Fig. 7.

Experiment 1–User forced-choice comparisons of preference across ROTs.

3.2.4 Discussion

Subjects' exit surveys and responses during the experiment provided useful information about each ROT. Subjects' reasons for favourably rating ROTs included: the method provided instruction (either audio or visual), they did not notice rotation, and the method was realistic or natural. We believe that D and HT were rated higher by subjects than T and TI because both rotate the VE while the subject is stimulating the vestibular system by turning her head and is less likely to notice the rotation of the VE.

We found subjects were confused during the first few sub-trials of T and often needed extra instruction from the experimenter to determine which direction to walk in the lab. After the first sub-trial of T one subject exclaimed, “Where am I?” and had to be stopped before walking out of the lab space. This occurred with several subjects, however after three sub-trials subjects often no longer needed extra instruction to determine the correct direction to walk in the lab. Subjects described T as dizzying, and complained about having no orientation in the VE after the world “spun.” Some subjects found T to be “fun” and simple because the subject just waited for “the flip” and then the virtual would moved as they expected.

Subjects were occasionally confused by the audio instructions in TI asking for the subject to turn 360° but seeing the VE stop rotating after the subject only turned 180°. Subjects would occasionally turn 360° in the real world and then turn an additional 180° to walk the correct direction along the path. Subjects also noticed the VE spinning at a much faster rate than they were turning. One subject complained about the disembodied voice that did not fit into the environment. Subjects praised this technique for giving them some control over the VE by spinning when the subject turned and subjects also found audio instructions helpful for determining how to turn around in the VE.

When using HT, subjects complained about noticing the path in VE not being in the right place once they started turning their heads but also commented on not seeing the rotation as much as other ROTs. Some subjects would occasionally stop turning their heads before the VE had rotated 180° and would stand and wait until given more instruction to continue turning their heads. These subjects would no longer need extra instruction after three sub-trials. Subjects liked having control over the rotation of the VE that was offered by turning their heads.

Subjects commented that the distractor was dizzying because it moved too fast, or that they would not be able to turn their heads fast enough to keep it in view. Subjects also complained that a “big red ball is not normal.” Some subjects also complained about the ball's sudden appearance and disappearance. Other subjects found D entertaining and engaging and found that when looking at the ball they were not paying attention to the moving scenery.

Our results revealed that D and HT were better ROTs than TI and T by producing increased presence, having higher user preference and being more natural to the user. However, user feedback suggested further improvements that were explored in Experiment 2.

3.3 Experiment 2

Based on the results and user feedback from Experiment 1, we improved our distractor method by using a butterfly instead of a sphere because it is more natural for the VE being used. The butterfly model is shown in Figure 9. We also had the butterfly fly in and out of the VE instead of suddenly appearing and disappearing, a common user complaint about the distractor from Experiment 1. We compared our improved distractor to the most promising ROTs from Experiment 1: our original red sphere distractor and head turn with audio instruction [7].

Fig. 9.

Butterfly used in Experiment 2.

To have the butterfly appear more life like and due to the complaints from Experiment 1 that the distractor was “dizzying,” we slowed the speed at which the butterfly flew around the subject. To compare the difference in natural versus unnatural distractors we also changed the speed of the sphere to match that of the butterfly.

3.3.1 Participants

Twelve participants (6 men and 6 women), most computer science graduate students in their twenties, participated in the experiment. Each subject visited the laboratory once for a session lasting approximately 1 hour and received $7.50 for participation during the week and $10.00 for weekend participation. All subjects had normal or corrected to normal vision and were naive to the purpose of the study. Participants were not informed about ROTs and were initially unaware that the VE would rotate.

3.3.2 Experimental Design

Experiment 2 consisted of two parts, both taking place in the same VE. The VE was an outdoor space similar to Experiment 1, with a 180-meter straight wooden path and square markers placed 5 meters apart along the path. The environment is shown in Figure 1. Subjects were instructed to walk along the designated path in the environment and to stop at each marker along the path. Once a subject had reached a marker, the subject experienced one of three reorientation techniques:

Head turn with audio instruction (HT)

Audio instructions in the VE, presented via headphones, ask the user to turn her head back and forth and then continue walking along the path. While the user turns her head the rotation applied to the VE is 1.3 times the rotation speed of the user's head until the VE has rotated 180°. The participant reorients herself by rotating 180° in the real world. This is similar to a method described in [7].

Head turn with visual instruction, distractor (D)

A moving sphere appears in front of the user. The user watches the sphere as it moves in a horizontal arc and continues walking along the path once the sphere disappears. The rotation applied to the VE is 1.5 times the rotation speed of the user's head until the VE has rotated 180°. The distractor moves along the arc with sinusoidal displacement, amplitude = 0.5 meters and frequency = 2°/second. The user reorients herself by rotating 180° in the real world. The path and velocity of the distractor are described in Figure 3.

Head turn with visual instruction, improved distractor (ID)

A butterfly flies into the scene towards the subject, and then flies in a horizontal arc in front of the subject. The subject continues walking along the path once the butterfly flies away. While the user is watching the butterfly the rotation applied to the VE is 1.5 times the rotation speed of the user's head until the VE has rotated 180°. The distractor moves along the arc with sinusoidal displacement, amplitude = 0.5 meters and frequency = 2°/second. The user reorients herself by rotating 180° in the real world.

Part I of the experiment assessed the user's subjective sense of presence, how aware the user was of turning around, and how aware the user was of the VE rotation. Part I consisted of three trials, each using one ROT. The order of the trials was counterbalanced among subjects. Each trial was comprised of eight sub-trials requiring the subject to walk along the virtual path to the next marker along the path. Once the subject reached a marker a ROT would stop the subject and rotate the VE. Each trial consisted of walking to eight markers, experiencing the same ROT eight times. Subjects then removed the HMD and filled out the SUS presence questionnaire. In addition to the presence questionnaire, subjects also answered the following question:

Did you notice anything unnatural or odd during your virtual experience? Please rate the following on a scale from 0 to 7. Where 0 = did not notice or happen, 7 = very obvious and took away from my virtual experience.

___I felt like I was turning around

___I saw the virtual world get smaller or larger

___I saw the virtual world flicker

___I saw the virtual world rotating

___I felt like I was getting bigger or smaller

___I saw the virtual world get brighter or dimmer

We embedded questions of interest, those about the VE rotating and the subject turning, and analyzed only the results for those questions.

Part II consisted of 6 trials, each with two ROTs. Trials were counterbalanced and each ROT was compared to every other ROT twice with order reversed to remove the possibility of order effects. Each trial required the subject to walk to a marker, experience an ROT, and then walk to the next marker and experience a different ROT. The subject then made a forced-choice decision as to which ROT they preferred and which ROT was most natural. Subjects were also asked to explain why they chose one ROT over another.

At the end of the experiment, subjects filled out an exit survey and ranked the three ROTs based on naturalness and preference.

3.3.3 Results

Tables 3 and 4 and Figures 10 through 15 show our results from Experiment 2. The analysis of the SUS presence scores was done in the same manner as reported in Section 3.2.3. Tables 3 and 4 show the proportion of HIGH responses for each of the three conditions and the results of the pairwise contrasts of conditions. We found no statistical significance with user reported presence scores between ROTs.

TABLE 3.

Experiment 2 - Mean percentage of HIGH scores on SUS Presence Questionnaire

| ROT | x̄ |

|---|---|

| ID | 0.52778 |

| D | 0.45833 |

| HT | 0.41667 |

TABLE 4.

Experiment 2 - Results of Logistic Regression of SUS Presence Questionnaire

| Contrast | χ2(1) | p(α = 0.05) |

|---|---|---|

| ID vs. D | 1.09 | 0.2974 |

| ID vs. HT | 1.72 | 0.1895 |

| D vs. HT | 0.63 | 0.4291 |

Fig. 10.

Experiment 2–Legend

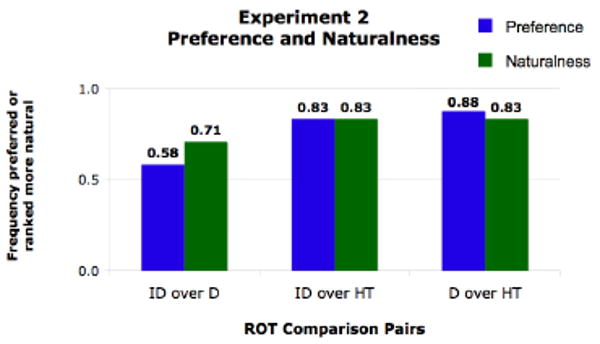

Fig. 15.

Experiment 2–User forced-choice comparisons of preference and naturalness across ROTs.

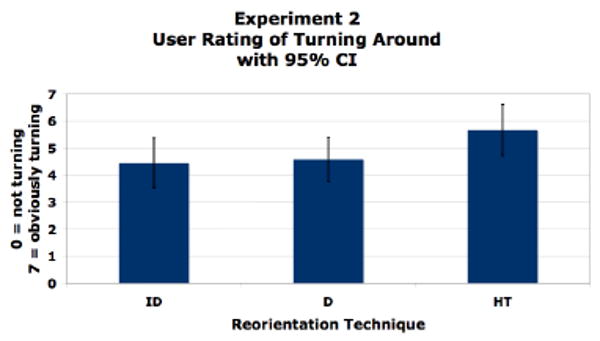

Figure 11 shows average user scores by ROT of response to the question about feeling like they were turning around. We analysed the data using Friedman's ANOVA and found significant differences between ROTs: χ2(2) = 7.550, p < 0.05. Wilcoxon tests were used to follow-up this finding. A Bonferroni correction was applied and all effects are reported at a 0.025 level of significance. Subjects significantly felt like they were turning more in HT than D (T′ = 51.50, r = 0.74), and a trend was found with subjects feeling like they were turning more in HT than ID (T′ = 46.50, r = 0.56).

Fig. 11.

Experiment 2–User rating - “I felt like I was turning around.”

Figure 12 shows average user scores by ROT of response to the question about subjects noticing that the VE was rotationg. Using Friedman's ANOVA we found no significant difference between ROTs: χ2(2) = 3.630, p = 0.187.

Fig. 12.

Experiment 2–User rating - “I saw the virtual world rotating.”

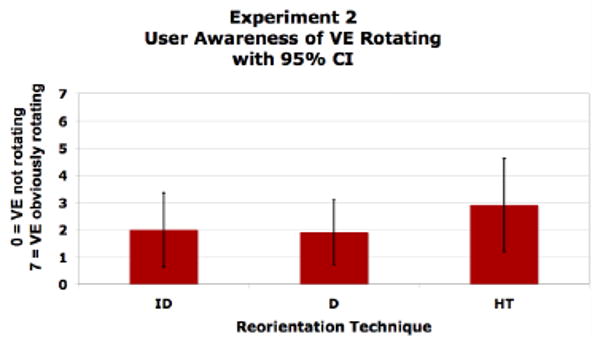

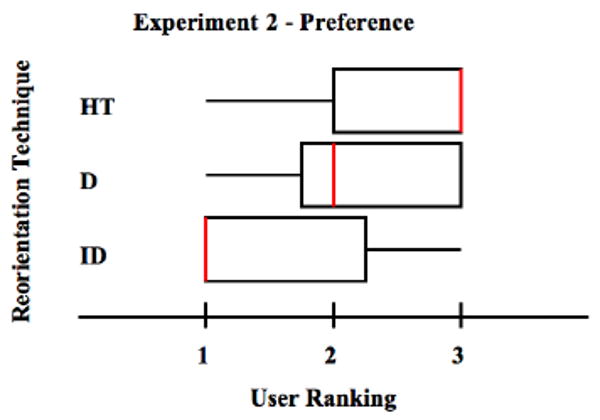

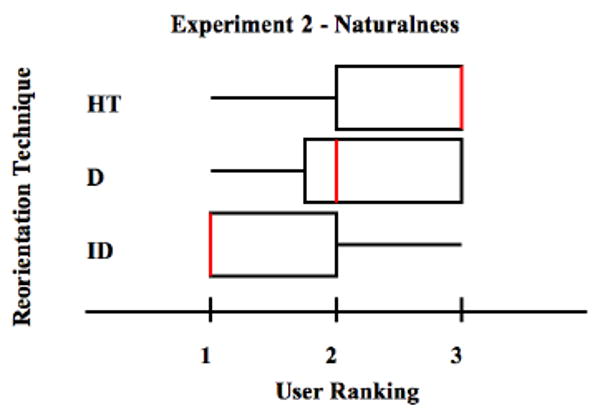

Figures 13 and 14 show results from user ranked preference and naturalness by ROT, with 1 being the highest preference and 3 being the lowest. Trends were found between ROTs and subject rankings of preference (χ2(2) = 4.667, p = 0.108) and subject ranked naturalness (χ2(2) = 5.167, p = 0.080).

Fig. 13.

Experiment 2–User rated preference scores from 1 (most preferred) to 3 (least preferred). Standard box-and-whisker plots with the median in red.

Fig. 14.

Experiment 2–User rated naturalness scores from 1 (most natural) to 3 (least natural). Standard box-and-whisker plots with the median in red.

Figure 15 shows user preference and user-ranked naturalness of paired ROTs. The frequency at which a subject preferred one ROT over another was compared to random choice, a frequency of 0.50, using Wilcoxon tests. Subjects preferred both ID and D to HT (T′ = 65.00, r = 0.47, and T′ = 77.00, r = 0.51 respectively), and ranked ID and D to be more natural than HT (T′ = 82.50, r = 0.44, and T′ = 65.00, r = 0.47 respectively). A trend suggests that ID is more natural than D (T′ = 63.00, r = 0.28, p = 0.11).

3.3.4 Discussion

The results from Experiment 2 suggest ROTs that use distractors reduce the likeness of a users' feeling as if they are turning around while being reoriented. The results also suggest that subjects prefer ROTs with distractors and consider them to be more natural. We account for the difference between D and HT in Experiment 2 compared to Experiment 1 by the reduced speed of the sphere from 8°/sec to 2°/sec.

The VE rotates 1.3 times the rotation speed of the user's head in HT and 1.5 times the rotation speed of the user's head in D and ID. This difference in VE rotation relative to to head turn speed may explain why there was no significant difference between ROTs and user awareness of the VE rotating. Further studies comparing different rotation speeds of the VE relative to head turn speeds may reveal further differences between ROTs with and without distractors.

Exit surveys and responses during Experiment 2 again provided useful information about each ROT. In the HT condition subjects found turning their heads back and forth for no reason to be annoying and “silly.” One subject noted, “The voice destroys being there.” Subjects were aware that the path had moved when they rotated their heads and complained of being more lost than with visual instruction. Two subjects found HT to provide more freedom and the ability to look around the environment during reorientation.

Subjects found D to be easy to follow and some subjects found D less distracting than the flapping butterfly wings of ID. Subjects continued to complain about the sphere not being natural to the environment and noted that it “defies the laws of physics.” Subjects commented on the naturalness of the butterfly, but some found the flapping of the butterfly wings to be “annoying.” Subjects enjoyed watching the butterfly fly in and out of the scene but, in Experiment 2, no negative comments were made about the sudden appearance and disappearance of the sphere. Based on the numerous complaints about the sudden appearance and disappearance of the sphere in Experiment 1, we believe the distractor should engage the user in a manor natural to the scene.

3.4 Experiment 3

Based on user feedback from Experiment 2, we improved our distractor method by using a more realistic model: a hummingbird (Figure 16). In addition to using a more realistic model created using a realistic texture map and modeled by an artist, we explored adding sound to our visual distractor and using sound alone as a distractor. All distractors in this experiment had the same motion path and speed of the butterfly from Experiment 2.

Fig. 16.

Hummingbird used in Experiment 3.

3.4.1 Participants

Twelve participants, most graduate students and researchers (7 men and 5 women) participated in the experiment. The age range was 23 to 50, with an average age of 32. Each subject visited the laboratory once for a session lasting approximately 1 hour and received $7.50 for participation during the week and $10.00 for weekend participation. All subjects had normal or corrected to normal vision and were naive to the purpose of the study. Participants were not informed about ROTs and were initially unaware that the VE would rotate.

3.4.2 Experimental Design

Experiment 3 consisted of two parts, both taking place in the same VE. The VE was the same as Experiment 2 and consisted of a 180-meter straight wooden path with square markers placed 5 meters apart along the path. Subjects were instructed to walk along the path in the environment and to stop at each marker along the path. Upon reaching each marker, the subject experienced one of three ROTs:

Distractor, visual (DV)

A hummingbird flies into the scene towards the subject, and then flies in a horizontal arc in front of the subject. The subject continues walking along the path once the hummingbird flies away. While the user is watching the hummingbird the rotation applied to the VE is 1.5 times the rotation speed of the user's head until the VE has rotated 180°. The distractor moves along the arc with sinusoidal displacement, amplitude = 0.5 meters and frequency = 2°/second. The user reorients herself by rotating 180° in the real world.

Distractor, visual and audio (DVA)

A hummingbird flies into the scene towards the subject, and then flies in a horizontal arc in front of the subject. The hummingbird is accompanied by spatialized audio of hummingbird wings flapping, presented via headphones. The hummingbird has sinusoidal displacement along the arc, amplitude = 0.5 meters and frequency = 2°/second. The subject continues walking along the path once the hummingbird flies away. While the user is watching the hummingbird the rotation applied to the VE is 1.5 times the rotation speed of the user's head until the VE has rotated 180°. The user reorients herself by rotating 180° in the real world.

Distractor, audio (DA)

A sound of hummingbird wings flapping flies into the scene towards the subject, and then spatially moves in a horizontal arc in front of the subject. The sound has sinusoidal displacement along the arc, amplitude = 0.5 meters and frequency = 2°/second. There is no visual hummingbird to accompany the sound. The subject continues walking along the path once the sound of the hummingbird flies away. While the user is listening to the hummingbird the rotation applied to the VE is 1.5 times the rotation speed of the user's head until the VE has rotated 180°. The user reorients herself by rotating 180° in the real world.

Experiment 3 had the same experimental design as Experiment 2. Part I of the experiment assessed the user's subjective sense of presence, how aware the user was of turning around, and how aware the user was of the VE rotation. Part I consisted of three trials, each using one ROT. The order of the trials was counterbalanced among subjects. Each trial was comprised of eight sub-trials requiring the subject to walk along the virtual path to the next marker along the path. Once the subject reached a marker a ROT would stop the subject and rotate the VE. Each trial consisted of walking to eight markers, experiencing the same ROT eight times. Subjects then removed the HMD and filled out the SUS presence questionnaire. In addition to the presence questionnaire, subjects also answered the embedded questions about the VE rotating and the user turning around that were presented in Experiment 2.

Part II consisted of 6 trials, each with two ROTs. Trials were counterbalanced and every ROT was compared to every other ROT twice with order reversed to remove possibile of order effects. Each trial required the subject to walk to a marker, experience a ROT, and then walk to the next marker and experience a different ROT. The subject then made a forced-choice decision as to which ROT they preferred and which ROT was more natural. Subjects were also asked to explain why they chose one ROT over another.

At the end of the experiment, subjects filled out an exit survey and ranked the three ROTs based on naturalness and preference.

3.4.3 Results

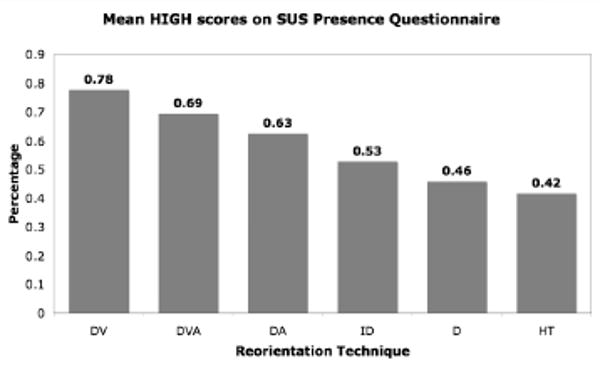

Tables 5 and 6 and Figures 17 through 23 show the results from Experiment 3. The analysis of the SUS presence scores was performed in the same manner as reported in Section 3.2.3. Tables 5 and 6 show the proportion of HIGH responses for each of the three conditions and the results of the pairwise contrasts of conditions. We found users felt significantly more present in DV than DA (χ2(1) = 6.23, p < 0.05).

TABLE 5.

Experiment 3 - Mean percentage of HIGH scores on SUS Presence Questionnaire

| ROT | x̄ |

|---|---|

| DV | 0.77780 |

| DA | 0.62500 |

| DVA | 0.69444 |

TABLE 6.

Experiment 3 - Results of Logistic Regression of SUS Presence Questionnaire. Statistically significant results are marked with a box.

| Contrast | χ2(1) | p(α = 0.05) |

|---|---|---|

| DV vs. DA | 6.23 | 0.0126 |

| DV vs. DVA | 1.60 | 0.2060 |

| DVA vs. DA | 1.99 | 0.1581 |

Fig. 17.

Experiment 3–Legend

Fig. 23.

Experiment 3–User forced-choice comparisons of preference and naturalness across ROTs.

Experiments 2 and 3 used an identical experimental design: participants perform the same number of trials and used the same environment. Also, subjects for both experiments were mostly computer scientists and researchers. Since the subjects came from the same pool, we were able to compare presence scores between Experiment 2 and Experiment 3. Table 7 and Figure 18 show the proportion of HIGH responses for each of the three conditions and the results of the pairwise contrasts of conditions. We found users felt significantly more present in DV than ID, D, and HT (χ2(1) = 6.18, p < 0.05, χ2(1) = 10.73, p < 0.01, χ2(1) = 10.44, p < 0.01 respectively). Users statistically felt more present in DVA than D and HT (χ2(1) = 7.76, p < 0.01, χ2(1) = 9.06, p < 0.01, respectively), and a trend suggests that users feel more present in DVA than ID (χ2(1) = 3.29, p = 0.07). Users also felt significantly more present in DA than D and HT (χ2(1) = 3.84, p = 0.05, χ2(1) = 6.60, p < 0.05, respectively).

TABLE 7.

Experiments 2 and 3 - Results of Logistic Regression of SUS Presence Questionnaire. Statistically significant results are marked with a box.

| Contrast | χ2(1) | p(α = 0.05) |

|---|---|---|

| DV vs. ID | 6.18 | 0.0129 |

| DV vs. D | 10.73 | 0.0011 |

| DV vs. HT | 10.44 | 0.0012 |

| DVA vs. ID | 3.29 | 0.0699 |

| DVA vs. D | 7.76 | 0.0053 |

| DVA vs. HT | 9.06 | 0.0026 |

| DA vs. ID | 1.09 | 0.2969 |

| DA vs. D | 3.84 | 0.0500 |

| DA vs. HT | 6.60 | 0.0102 |

Fig. 18.

Experiments 2 and 3–User rating - Mean percentage of HIGH scores on SUS Presence Questionnaire.

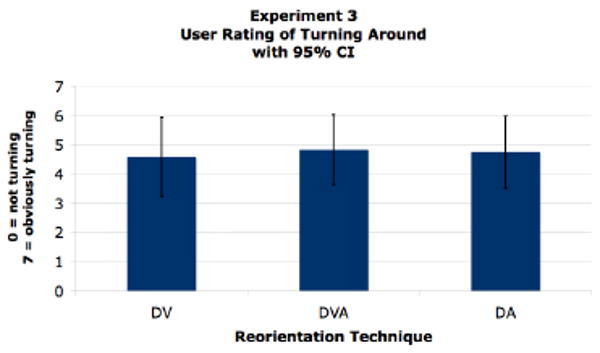

Figure 19 shows average scores of response to the question about feeling like they were turning around for each ROT. We analysed the data using Friedman's ANOVA and found no significant differences between ROTs: χ2(2) = 0.712, p = 0.514.

Fig. 19.

Experiment 3–User rating - “I felt like I was turning around.”

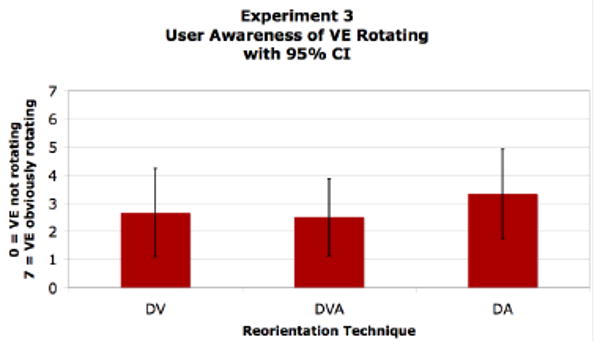

Using Friedman's ANOVA we found no significant difference between ROTs and subjects noticing that the VE (Figure 20) was rotating χ2(2) = 1.372, p = 0.298.

Fig. 20.

Experiment 3–User rating - “I saw the virtual world rotating.”

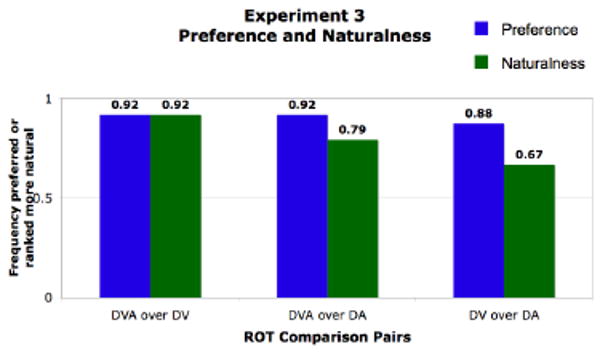

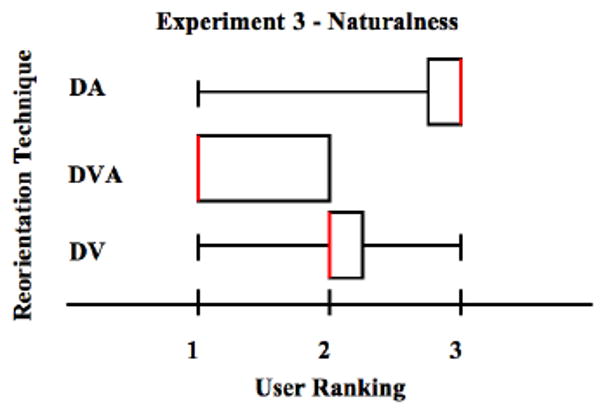

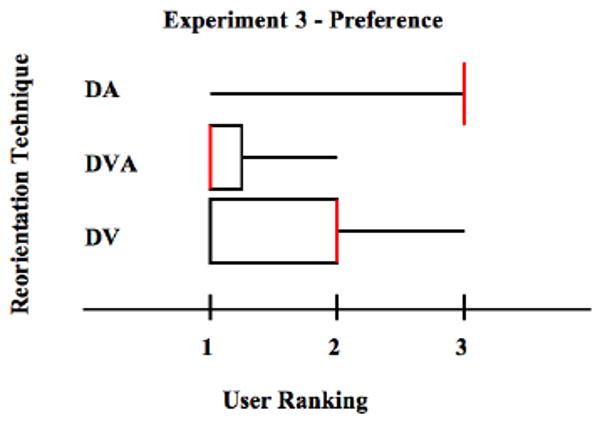

Figures 22 and 21 show subjects' ranked preference and naturalness of ROTs with 1 being the highest rank and 3 being the lowest. We found significant differences between ROTs of subject ranked preference (χ2(2) = 16.875, p < 0.05) and subject ranked naturalness (χ2(2) = 102.308, p < 0.001). Wilcoxon tests were used to follow-up this finding. A Bonferroni correction was applied and all effects are reported at a 0.025 level of significance. Subjects significantly preferring DVA to DV and DA (T′ = 66.00, r = 0.352, and T′ = 75.50, r = 0.433 respectively), and a trend was found with subjects preferred DV to DA (T′ = 62.00, r = 0.306). Subjects ranked DVA to be more natural than DV and DA, (T′ = 66.00, r = 0.387, and T′ = 72.00, r = 0.342 respectively).

Fig. 22.

Experiment 3–User rated naturalness scores from 1 (most natural) to 3 (least natural). Standard box-and-whisker plots with the median in red.

Fig. 21.

Experiment 3–User rated preference scores from 1 (most preferred) to 3 (least preferred). Standard box-and-whisker plots with the median in red.

Figure 23 shows user preference and user-ranked naturalness of paired ROTs. The frequency at which a subject preferred one ROT over another was compared to random choice, a frequency of 0.50, using Wilcoxon tests. Subjects preferred DVA to both DV and DA (T′ = 55.00, r = 0.575, and T′ = 55.00, r = 0.575 respectively). Subjects also preferred DV to DA (T′ = 60.00, r = 0.45). Subjects ranked DVA to to be more natural than both DV and DA (T′ = 55.00, r = 0.575, and T′ = 54.00, r = 0.352 respectively).

3.4.4 Discussion

The results from Experiment 3 suggest that users felt increased presence with a realistic visual distractor without audio than with only an audio distractor. We performed contrasts between Experiment 2 and 3 and found that improving the visual quality of the distractor from an unrealistic butterfly to a more realistic hummingbird produced a higher feeling of presence among users. Note that the motion path and animation of the distractors was not modified between Experiments 2 and 3. Our results suggest that using more realistic distractors can increase a user's feeling of presence.

Adding natural audio sounds to a visual distractor resulted in no significant increase of user-reported presence when compared to a visual distractor without audio. However, users prefer the addition of audio cues to the visual distractor and find the audio plus visual stimuli to be more natural than visual or audio alone. Many users claimed that the hummingbird with the sound of wings flapping stimulated more senses and was therefore more natural. No significant change in user-reported presence was found when the visual cue of the hummingbird was removed and only the three-dimensional audio cues were presented to the user.

When comparing presence data from Experiment 2 and Experiment 3, we found that natural audio as a distractor without visual cues produces a higher sense of presence than using the unnatural red sphere distractor from Experiment 2. The ability to use only audio as a distractor extends the range of VEs in which distractors are applicable. Possible applications for audio distractors include military applications where environment appropriate moving visual objects in front of the user are not possible. Military training applications may have loud noises or explosions that naturally suit the environment and can be used as distractors. However, further studies need to be conducted to determine if distractors cause miss-training in military applications. Audio distractors may be useful for VEs because they do not require model changes and modeling and animation expertise.

One user commented that the audio distractor was hard to track and while he was searching to find the (audio) hummingbird he was much less aware of the VE rotating. Other users found the audio frustrating because they had a hard time determining where the hummingbird was located. This may be the reason that users ranked the audio distractor lower than the distractors with a visual hummingbird. Users may prefer natural distractors with audio to audio distractors but audio distractors may still be effective.

4 Conclusion

We successfully implemented and tested eight ROTs to handle the worst-case scenario in large-walking VEs–when the user is about to walk out of the tracked space. Five of these ROTs use a novel technique, distractors–objects in the VE that the user focuses on while the VE rotates–to minimize the observed rotation of a VE during reorientation. In addition to reducing observed rotation of the VE, ROTs using distractors were preferred and ranked more natural by users than currently available ROTs that do not use distractors. We also found subjects were less aware of physically turning around in the VE when reorienting using distractors.

Based on user feedback, ROTs should be realistic and the user should not notice the rotation of the VE. Unlike non-distractor ROTs, distractors can be realistic and our results suggest distractors reduce the likelihood of perceiving VE rotation during reorientation. Distractors should also exhibit smooth movements that are easy and interesting to watch. Improving the realism of the distractor increases a user's feeling of presence and adding natural audio to a visual distractor is preferred and considered more natural to users than using a visual or audio distractor alone.

An audio distractor doesn't produce as high a feeling of presence as a natural audio-visual distractor, however it does produce a higher feeling of presence than an unnatural distractor without audio. Audio distractors can be easier to implement than visual distractors as they require so model changes. Audio distractors may also be useful for VEs in which the addition of visual distractors may be unnatural or detract from the VE experience.

We believe that optimal distractors are VE-dependent and should be designed to be as natural as possible to the VE. Possible implementations of distractors include: exploring a virtual house and having a dog run by, walking through a virtual art museum and having a docent point you in a new direction, and training dismounted infantry to successfully navigate enemy territory while snipers are heard in the distance.

Distractors allow users to move by really walking in VEs that are larger than the tracked lab space; however, further investigation is needed to determine the potential effects of using distractors. Potential future work includes examining cognitive load effects that may hinder training applications, and exploring speed, appearance, and motion paths of distractors. Other areas of research include comparing really walking with distractors to other virtual locomotion-systems such as walking-in-place and flying that also allow users to explore large virtual spaces.

Fig. 2.

Laboratory Layout used in Experiment 2 and 3.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work was provided by the NIH National Institure of Biobedical Imagind and Bioengineering, the Office of Naval Research VIRTE project, and the Link Foundation. The authors would like to thank Dorian Miller who first experimented with distractors as a class project, Eric Knisley for making the hummingbird model and the EVE team and David Borland for moral support and help editing.

Biographies

Tabitha C. Peck received the BSc degree in computer science from Bucknell University in 2005 and the MSc in computer science from The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2007. She is currently a PhD candidate in the Department of Computer Science at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her research interests include virtual reality, locomotion, user studies, and navigation.

Henry Fuchs is the Federico Gil Professor of Computer Science and Adjunct Professor of Biomedical Engineering at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In 1975 he received a Ph.D. in Computer Science from the University of Utah.

Fuchs research interests include Office of the Future and 3D telepresence, wide-area multiprojector displays, and medical and surgical augmented-reality assistance.

Fuchs is a Fellow of the National Academy of Engineering, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the Association for Computing Machinery. He has won the Satava Award from Medicine Meets Virtual Reality, the Computer Graphics Achievement Award from ACM/SIGGRAPH, and the National Computer Graphics Association Academic Award. He has co-authored more than 150 articles and is inventor or co-inventor of seven U.S. patents.

Mary C. Whitton is a research associate professor of computer science at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She co-leads the Effective Virtual Environments research group that focuses on discovering what makes virtual environment systems effective and developing techniques to make them more effective for applications such as simulation, training, and rehabilitation. Prior to joining UNC in 1994, she was co-founder of two companies that produced high-end hardware for graphics, imaging, and visualization. Ms. Whitton has held leadership roles in ACM SIGGRAPH including serving as President 1993-1995. She is a member of the IEEE and the IEEE Computer Society.

Contributor Information

Tabitha C. Peck, Email: tpeck@cs.unc.edu, Department of Computer Science, The University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, 27599

Henry Fuchs, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Mary C. Whitton, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

References

- 1.Slater M, Usoh M, Steed A. Taking steps: the influence of a walking technique on presence in virtual reality. ACM Trans Comput-Hum Interact. 1995;2(no 3):201–219. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Usoh M, Arthur K, Whitton MC, Bastos R, Steed A, Slater M, Frederick J, Brooks P. Walking > walking-in-place > flying, in virtual environments. SIGGRAPH '99: Proceedings of the 26th annual conference on Computer graphics and interactive techniques; New York, NY, USA: ACM Press/Addison-Wesley Publishing Co.; 1999. pp. 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darken RP, Cockayne WR, Carmein D. The omni-directional treadmill: a locomotion device for virtual worlds. UIST '97: Proceedings of the 10th annual ACM symposium on User interface software and technology; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 1997. pp. 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nitzsche N, Hanebeck UD, Schmidt G. Motion compression for telepresent walking in large target environments. Presence: Teleoper Virtual Environ. 2004;13(no 1):44–60. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Razzaque S, Kohn Z, Whitton MC. Tech Rep TR01-007. Chapel Hill, NC, USA: 2001. Redirected walking. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razzaque S, Swapp D, Slater M, Whitton MC, Steed A. Redirected walking in place. EGVE '02: Proceedings of the workshop on Virtual environments 2002; Aire-la-Ville, Switzerland, Switzerland: Eurographics Association; 2002. pp. 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Razzaque S. PhD dissertation. University of North Carolina; Chapel Hill: 2005. Redirected walking. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su J. Motion compression for telepresence locomotion. Presence: Teleoper Virtual Environ. 2007;16(no 4):385–398. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams B, Narasimham G, McNamara TP, Carr TH, Rieser JJ, Bodenheimer B. Updating orientation in large virtual environments using scaled translational gain. APGV '06: Proceedings of the 3rd symposium on Applied perception in graphics and visualization; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2006. pp. 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams B, Narasimham G, Rump B, McNamara TP, Carr TH, Rieser J, Bodenheimer B. Exploring large virtual environments with an hmd on foot. APGV '06: Proceedings of the 3rd symposium on Applied perception in graphics and visualization; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2006. pp. 148–148. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brooks FP. Walkthrough: a dynamic graphics system for simulating virtual buildings. SI3D '86: Proceedings of the 1986 workshop on Interactive 3D graphics; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 1987. pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen RR, Hollerbach JM, Xu Y, Meek SG. Inertial-force feedback for the treadport locomotion interface. Presence: Teleoper Virtual Environ. 2000;9(no 1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwata H. Walking about virtual environments on an infinite floor. VR '99: Proceedings of the IEEE Virtual Reality; Washington, DC, USA: IEEE Computer Society; 1999. p. 286. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slater M, Steed A, Usoh M. The virtual treadmill: a naturalistic metaphor for navigation in immersive virtual environments. VE '95: Selected papers of the Eurographics workshops on Virtual environments '95; London, UK: Springer-Verlag; 1995. pp. 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peck T, Whitton M, Fuchs H. Evaluation of reorientation techniques for walking in large virtual environments. Virtual Reality Conference, 2008 VR '08; March 2008.IEEE; pp. 121–127. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Interrante V, Ries B, Anderson L. Seven league boots: A new metaphor for augmented locomotion through moderately large scale immersive virtual environments. 3D User Interfaces, 2007 3DUI '07 IEEE Symposium on; March 2007.p. –. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams B, Narasimham G, Rump B, McNamara TP, Carr TH, Rieser J, Bodenheimer B. Exploring large virtual environments with an hmd when physical space is limited. APGV '07: Proceedings of the 4th symposium on Applied perception in graphics and visualization; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2007. pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohli L, Burns E, Miller D, Fuchs H. Combining passive haptics with redirected walking. ICAT '05: Proceedings of the 2005 international conference on Augmented tele-existence; New York, NY, USA: ACM; 2005. pp. 253–254. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slater M, Usoh M. Presence in immersive virtual environments. VR '93: Proceedings of the IEEE Virtual Reality; Washington, DC, USA: IEEE Computer Society; 1993. pp. 90–96. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slater M, Usoh M, Steed A. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments. Vol. 3.2. MIT Press; 1994. Depth of presence in virtual environments; pp. 130–144. [Online]. Available: citeseer.ist.psu.edu/slater94depth.html. [Google Scholar]