Abstract

The role of the L-type calcium channel (Cav1.2) as a molecular switch that triggers secretion prior to Ca2+ transport has previously been demonstrated in bovine chromaffin cells and rat pancreatic beta cells. Here, we examined the effect of specific Cav1.2 allosteric modulators, BayK 8644 (BayK) and FPL64176 (FPL), on the kinetics of catecholamine release, as monitored by amperometry in single bovine chromaffin cells. We show that 2 μm BayK or 0.5 μm FPL accelerates the rate of catecholamine secretion to a similar extent in the presence either of the permeable Ca2+ and Ba2+ or the impermeable charge carrier La3+. These results suggest that structural rearrangements generated through the binding of BayK or FPL, by altering the channel activity, could affect depolarization-evoked secretion prior to cation transport. FPL also accelerated the rate of secretion mediated by a Ca2+-impermeable channel made by replacing the wild type α11.2 subunit was replaced with the mutant α11.2/L775P. Furthermore, BayK and FPL modified the kinetic parameters of the fusion pore formation, which represent the initial contact between the vesicle lumen and the extracellular medium. A direct link between the channel activity and evoked secretion lends additional support to the view that the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels act as a signaling molecular switch, triggering secretion upstream to ion transport into the cell.

Keywords: Ion Channels, Neuroscience, Neurotransmitters, L-type Channel, Amperometry, Chromaffin Cells, Depolarization-evoked Secretion, Exocytosis

Introduction

The kinetic properties of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCC)2 are determined by the conformational changes induced at the channel during membrane depolarization. The kinetics of the L-type VGCC Cav1 is modulated also by allosteric agonists, which include BayK 8644 (BayK), a 1,4-dihydropyridine, FPL64176 (FPL), and CGP 48506 (1–9). BayK, FPL, and CGP 48506, which are structurally unrelated, interact with the cardiac Cav1.2 channel through binding within discrete sites at the transmembrane and extracellular loops of the α11.2 pore-forming subunit (10–14).

BayK enhances macroscopic currents (15) by increasing the rate of transition to “mode 2” single channel behavior (16, 17) and the single channel currents by means of lengthening the channel open time (17–20). BayK binding at selective Cav1.2 regions alters indirectly the selectivity filter, in turn affecting ion permeability (21). The changes observed in channel deactivation and inactivation are sensitive to the type of the cation used as the charge carrier (17).

Like BayK 8644 (1), FPL is coupled to the cation binding at the selectivity filter of Cav1.1 acting as an allosteric regulator (22). In neonatal rat ventricular myocytes and rat ventricular cells, FPL enhances Ca2+ influx and slows both the activation and the inactivation kinetics of the Cav1.2 (23). In isolated rat ventricular myocytes, FPL slowed the transition of the channel to a closed or inactivated state (24). In GH3 cells, FPL increased Cav1.2 current amplitude and shifted the current-voltage relationship to negative voltages (25). Single channel analysis showed that FPL increased both the channel open time and probability in a voltage-dependent manner (25). It is well established that BayK and FPL enhance current amplitude and elevate cytosolic Ca2+ via Cav1.2 in chromaffin cells (26–29) similar to any L-type-expressing cells.

Previous studies have proposed that Cav1.2 is an integral part of the exocytotic machinery where it could act as a Ca2+ sensor protein of secretion (30–33). This proposition was initially originated from a specific physical and functional coupling between the channel and the exocytotic proteins (34–38). This model was further supported by results showing the ability of La3+ to support secretion by means of binding to the pore of the channel and in the absence of concomitant ion influx (31, 33, 39). Corroborating with the proposed model, secretion could be triggered by membrane depolarization in chromaffin cells where the normal α11.2 pore-forming subunit of Cav1.2 was replaced by a Ca2+-impermeable subunit α11.2/L775P (40).

We have explored this concept further, testing whether the mutually exclusive structural rearrangements conferred upon the channel by BayK or FPL could affect the kinetics of secretion in bovine chromaffin cells, prior to and independently of cation influx. To preclude the effects of FPL and BayK on Ca2+ influx in secretion, bovine chromaffin cells were stimulated to secrete by using the impermeable La3+ as a substituent charge carrier for Ca2+ or Ba2+ or by using the Ca2+-impermeable channel mutant α11.2/L775P (40).

We show that both BayK and FPL elevated the rate of secretion in the presence of La3+ despite the lack of La3+ influx, suggesting that a channel conformation induced by agonists binding, as opposed to cation influx, could enhance the rate of secretion. The essential role of the channel played in the excitation-secretion coupling prior to cation influx was highlighted by an increase in the rate of catecholamine release induced by FPL binding to the nonconducting Cav1.2. These results are consistent with the view that the channel acts as a signaling switch that is an integral part of the secretory machinery and provide for a deeper understanding of the molecular function of the VGCC in neuroendocrine secretion.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

BayK 8644, 1,4-dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-5-nitro-4-(2(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)pyridine-3-carboxylic acid methyl ester, was from Sigma. Stock of 10 mm in DMSO was diluted to 2 μm. Final DMSO concentration was 0.02%. FPL64176, methyl-2,5-dimethyl-4-(2-phenylmethyl)benzoyl-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylate, was from Sigma. FPL in 0.0001% DMSO was used at a final concentration of 0.5 μm. Nifedipine in 0.001% DMSO was used at a final concentration of 5 μm (Sigma). In a separate control experiment, 0.02–0.2% DMSO had no effect on secretion in chromaffin cells.

Chromaffin Cell Preparation and Culture

Bovine adrenal glands were obtained at a local slaughterhouse. The adrenal medulla cells were isolated as described previously (31), plated at a density of 5 × 104 cells/cm2 on glass coverslips placed in 35-mm plates, and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with ITS-X and PenStrep (Sigma). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and used for amperometric recordings 2–4 days after preparation at 23 °C.

Semliki Forest Virus Infection

Semliki Forest viruses of α11.2 (D1733) and α11.2/L775P mutant (41) were prepared, and chromaffin cells were infected as described previously (40).

Amperometric Recordings of Catecholamine Release from Chromaffin Cell

Amperometry recordings were carried out using 5-μm thin carbon fiber electrodes (CFE ALA Inc., Westbury, NY) and a VA-10 amplifier (NPI Electronic, Tamm, Germany) held at 800 mV as described previously (42). Cells were rinsed 3–4 times prior to the experiment and bathed during the recordings in iso-osmotic physiological Ca2+ solution (149 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm CaCl2, 10 mm glucose, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.3) at ∼23 °C (adjusted with NaOH), in Ba2+ solution (same as Ca2+ solution where 2 mm Ba2+ substituted for 2 mm Ca2+), and in La3+ solution (same as Ca2+ solution where 0.2 mm La3+ substituted for 2 mm Ca2+). La3+-mediated secretion in chromaffin cells is optimal at a concentration in the range of 0.1–0.2 mm for this trivalent ion (31). Individual cells were stimulated to release by a 30-s application of iso-osmotic 60 mm KCl buffer (K60) from an ∼3-μm-tipped micropipette placed 30 μm from the cell in the bath. BayK 8644 was applied to the bath at a final concentration of 2 μm and FPL at 0.5 μm. Amperometric currents were sampled at 10 kHz, using Clampex 9.2 (Axon Instruments) and low pass-filtered at 0.2 kHz.

Amperometric Data Acquisition and Analysis

Amperometry records were analyzed with IGOR PRO (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR) to extract foot information according to the criteria of Chow et al. (42). The feet were analyzed for spikes >10 pA; peak-to-peak noise was ≤2 pA. The beginning of the foot was defined as the time when the signal exceeded the noise. The end of the foot was defined as the inflection point between the foot and the fast rise of the spike. The foot width corresponds to the lifetime of an open state (O) of a dynamic fusion pore (43), governed by the rate constants for dilation (D) and closure (C), (kc and kc (44)) as shown in Equation 1.

Mean fusion pore open time (τfp) was obtained by fitting a single exponential curve to the foot width distribution of each group (44).

Rates of secretion were determined for individual cells and averaged. The initial (10–30 s) and the sustained rates (60–180 s) of secretion were determined from initial and sustained slopes of the corresponding cumulative spike plot.

Data were analyzed as described in the text and figure legends. Error bars depict standard errors. Spikes exceeding three times the background noise (>10 pA) were analyzed. All peaks identified by the program were inspected visually, and bad quality signals were excluded manually. The number of foot analyzed is shown in supplemental Table SII.

RESULTS

BayK Accelerated the Frequency of Catecholamine Secretion in Chromaffin Cells

The functional impact of BayK binding to Cav1.2 on the kinetics of secretion was tested on bovine chromaffin cells, which despite expressing several types of VGCCs, N-type (Cav2.2), P/Q-type (Cav2.3), in addition to Cav1.2, can be induced to secrete catecholamines almost exclusively via Cav1.2 (45). Catecholamine release from large dense-core vesicles monitored as amperometry currents was elicited by a 30-s pulse of 60 mm KCl (K60) and detected by a carbon fiber electrode in single cells (42, 46, 47).

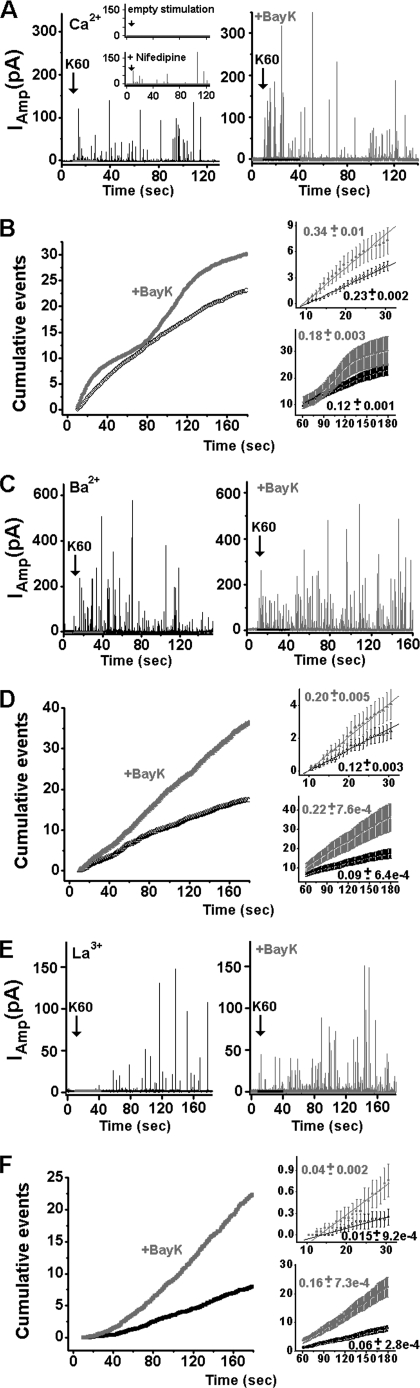

Single cells in a physiological solution containing 2 mm Ca2+, 2 mm Ba2+, or 0.2 mm La3+ were stimulated in the presence or absence of 2 μm BayK. Spike-like amperometric currents (spikes) were produced within ∼5 s of stimuli application (Fig. 1, A, C, and E). A recording for 30 s of spontaneous release was performed for each cell prior to stimulation. A physiological solution lacking K60 (empty stimulation; Fig. 1A, inset) failed to produce amperometric currents. Amperometric currents induced by K60 with 2 mm Ca2+ in the presence of 5 μm nifedipine were ∼90% reduced (Fig. 1A, inset).

FIGURE 1.

BayK-modified spike frequency as monitored by amperometry in chromaffin cells. A, amperometry currents were triggered by K60 (see “Experimental Procedures”) in the presence or absence of 2 μm BayK, using Ca2+ as the charge carrier. No amperometric currents were detected in the absence of K60 (top inset). Amperometric currents were blocked ∼90% in the presence of 5 μm nifedipine (bottom inset). B, left panel, spike frequency. Cumulative events per cell, averaged for cells with (n = 29) or without (n = 37) 2 μm BayK, were plotted versus time. Right panel, expanded view of the initial cumulative spike counts (upper panel) and sustained cumulative spike count (lower panel). The mean frequency of the initial rate was calculated as the maximum slope in plot B during the first 20 s of K60 stimulation (upper panel) (Table 1). The mean frequency of the sustained rate of secretion was calculated as the maximum slope during the time period of 60–180 s (lower panel). C and D, plots similar to those in A and B except that 2 mm Ba2+ (26 cells without and 30 cells with BayK) was used as the charge carrier. E and F, plots similar to A and B except for 0.2 mm La3+ (30 cells without and 21 cells with BayK). Means were calculated for individual cells as an average of more than 500 spike events.

The overall time course of secretion was determined from normalized waiting time distributions constructed by spike counting. Usually, a biphasic secretion was observed; an initial rate during the 10–30 s of stimulation (Fig. 1B, upper right panel) was followed by a slower sustained rate between 60 and 180 s (Fig. 1B, lower right panel). The rates of secretion were determined for individual cells and then averaged. The maximal slopes of the corresponding cumulative spike plots were taken to represent the initial and sustained rates of secretion.

With Ca2+ as the charge carrier, both the initial and the sustained rates of secretion were accelerated 1.5-fold in the presence of 2 μm BayK (Fig. 1, A and B; Table 1). BayK caused a multiphasic slope that might have promoted Ca2+-dependent inactivation of the channel by the robust increase in intracellular Ca2+ concentrations ([Ca2+]i). Additional studies are required to explore these findings.

TABLE 1.

Effect of BayK and FPL on the rates of secretion in Ca2+, Ba2+, or La3+

The rates were calculated from the maximal slopes of the cumulative spike count plots at the time intervals as indicated.

| Cation | Cells | Spikes | Frequency (spike/s)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial rate (10–30 s) |

Sustained rate (60–180 s) |

|||||

| n | n | ratio | ratio | |||

| Ca2+ | 37 | 916 | 0.23 ± 0.002 | 0.12 ± 0.001 | ||

| +BayKb | 29 | 542 | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 1.5 | 0.18 ± 0.003 | 1.5 |

| +FPLc | 28 | 727 | 0.31 ± 0.008 | 1.3 | 0.28 ± 0.005 | 2.3 |

| Ba2+ | 30 | 573 | 0.12 ± 0.003 | 0.09 ± 6.4e−4 | ||

| +BayK | 26 | 846 | 0.20 ± 0.005 | 1.7 | 0.22 ± 7.6e−4 | 2.4 |

| +FPL | 28 | 640 | 0.21 ± 0.005 | 1.8 | 0.22 ± 0.001 | 2.4 |

| La3+ | 30 | 524 | 0.015 ± 9.2e−4 | 0.06 ± 2.8e−4 | ||

| +BayK | 21 | 855 | 0.04 ± 0.002 | 2.7 | 0.16 ± 7.3e−4 | 2.7 |

| +FPL | 24 | 845 | 0.017 ± 0.002 | 1.1 | 0.13 ± 8.3e−4 | 2.1 |

a Cells were stimulated for 30 s by 60 mm KCl.

b Cells were stimulated for 30 s by 60 mm KCl in the presence of 2 μm BayK.

c Cells were stimulated for 30 s by 60 mm KCl in the presence of 0.5 μm FPL.

BayK accelerated the rate of secretion also in Ba2+ and La3+ (Fig. 1, C–F; Table 1). In Ba2+, the initial rate was increased 1.7-fold, and the sustained rate was increased 2.4-fold (Fig. 1D, right panel). In La3+, both the initial and the sustained rates were accelerated 2.7-fold (Fig. 1F; Table 1). The use of La3+ allowed us to distinguish the effect of BayK on secretion from subsequent intracellular ion elevation.

Effect of BayK on the Kinetic Parameters of Amperometric Spikes

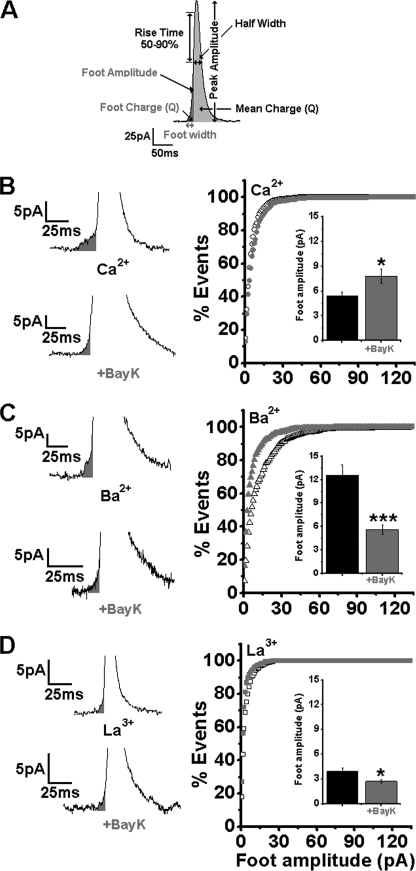

The peak amplitude, half-width, rise time of 50–90%, and mean charge of single amperometric events are depicted in Fig. 2A. For every parameter, the values from each cell were averaged and presented as the mean of cell averages ± S.E. for each group, assigning the same weight to each cell, regardless of the total number of spikes (supplemental Table SI) (48).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of BayK in Ca2+, Ba2+, or La3+ on foot amplitude in single chromaffin cells. A, presentation of single amperometric event kinetic properties of spikes. Peak amplitude, half-width, 50–90% rise time, and integrated spike (Q, gray area) are shown. Foot signal, foot width, foot amplitude, and integrated foot (Q, black area) are shown. Amperometric currents were triggered by a 30-s pulse of K60 from single cells. B, amperometric recording of the fusion of a single vesicle with or without 2 μm BayK in 2 mm Ca2+. B, right panel, cumulative distribution plot of foot number and analysis of foot amplitude in Ca2+. Inset, mean values for foot amplitude with or without BayK, n = 501, n = 911 events per data point, respectively. C, amperometric recording of the fusion of a single vesicle with or without 2 μm BayK in 2 mm Ba2+. C, right panel, data plotted in similar fashion as in B, right panel, in 2 mm Ba2+, n = 658; n = 494, respectively. D, amperometric recording of single vesicle fusion with or without 2 μm BayK in 0.2 mm La3+. D, right panel, data obtained in 0.2 mm La3+ plotted similar to B, right panel, with (n = 625) or without 2 μm BayK (n = 429). *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001.

BayK Modifies Pre-spike Foot Parameters

Amperometric spikes evoked by membrane depolarization are often preceded by a pre-spike current event (foot) corresponding to the open state of the fusion pore (Fig. 2A) (49). As shown previously, foot kinetics revealed significant differences when Ba2+ or La3+ was substituted for Ca2+ (33). These differences, illustrated by the foot traces shown in Fig. 2, B–D, and supplemental Table SII, were further accentuated by the presence of BayK, mainly in Ba2+ and La3+.

Foot amplitude, which designates the size of an open fusion pore, was elevated in the presence of BayK in Ca2+ (Fig. 2B) and lowered in Ba2+ and La3+ (Fig. 2, C and D; supplemental Table SII). In Ba2+, the foot width, which is indicative of the fusion pore stability, was significantly reduced by BayK (supplemental Fig. SIB, inset) but not in the presence of other charge carriers tested (supplemental Fig. SI, A and C, inset). The foot mean charge, which depends both on foot amplitude and foot width, was decreased in Ba2+ and unchanged in Ca2+ or La3+ (supplemental Table SII). The mean open time of the fusion pore corresponding to the lifetime of an open state (O) of a dynamic fusion pore (τfp) (see “Experimental Procedures”) (43) was computed by fitting a single exponential to the foot width distribution of each group as described by Wang et al. (44). BayK reduced τfp in Ba2+ and Ca2+ (supplemental Fig. SI, A and B, right panel) but not in La3+ (supplemental Fig. SIC, right panel and supplemental Table SII).

FPL Accelerated Frequency of Catecholamine Secretion

Similar to BayK, FPL was tested for its effect on secretion. Amperometric currents were recorded in several charge carriers because the enhancement of single L-type current in the hippocampal cells by FPL has been shown previously to be dependent on the type of ion bound at the selectivity filter (17, 50, 51).

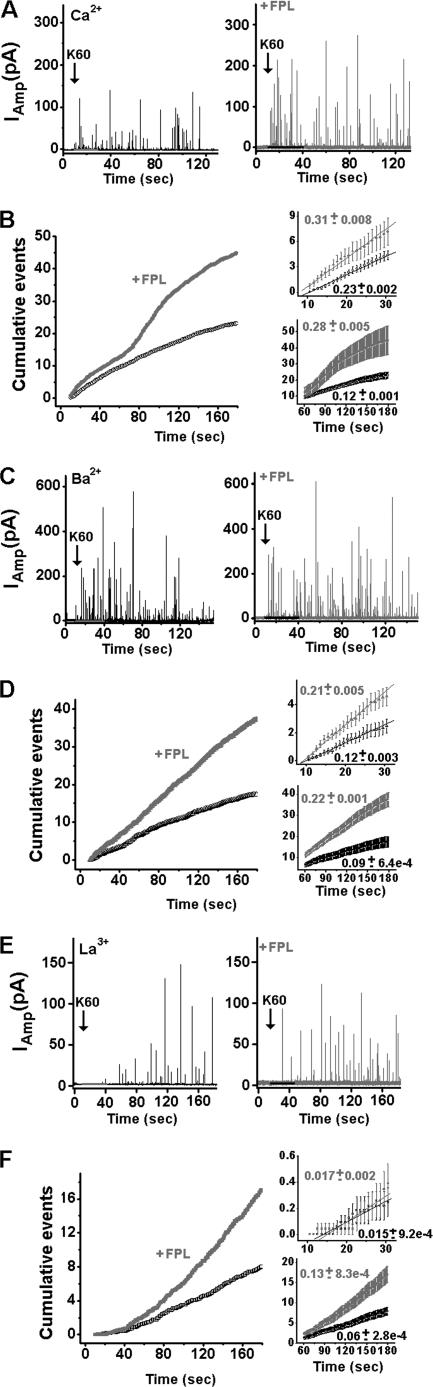

Single cells were stimulated with or without 0.5 μm FPL, replacing 2 mm Ca2+ with either 2 mm Ba2+ or 0.2 mm La3+. Spikes were produced following K60 stimulation (Fig. 3, A, C, and E). The rates of secretion were determined for individual cells and then averaged over the cells (Fig. 3B, left panel). The maximal slopes of the corresponding cumulative spike plots represent the initial rates at 10–30 s (Fig. 3B, right, upper panel) and sustained rates at 60–180 s (Fig. 3B, right, lower panel) of secretion.

FIGURE 3.

FPL-modified spike frequency in chromaffin cells. A, spike frequency (left panel). Cumulative events per cell, averaged for control or 0.5 μm FPL-treated cells, were plotted versus time; right panel, an expanded view of the initial cumulative spike counts (upper panel) and sustained cumulative spike counts (lower panel). The mean frequency of the initial rate was calculated as the maximum slope in plot B during the first 20 s of K60 stimulation (upper panel) (Table 1) and the mean frequency of the sustained rate of secretion during the time period of 60–180 s (lower panel). C and E, amperometry currents were triggered by K60 in the presence and in the absence of 0.5 μm FPL, using Ba2+ (C) or La3+ (E) as the charge carrier. D, plots similar to those in B with 2 mm Ba2+ and in F, with 0.2 mm La3+.

In Ca2+, 0.5 μm FPL accelerated both the initial (1.3-fold) and the sustained (2.3-fold) rates (Fig. 3B, right panel; Table 1). Similar to BayK, FPL generated a multiphase slope, which could promote a Ca2+-dependent inactivation of the channel due to the robust increase in Ca2+ influx. Further studies are required to explore these results.

The rate of secretion was increased by FPL in either Ba2+ or La3+ (Fig. 3, C–F). In Ba2+, the initial rate was increased 1.8-fold, and the sustained rate was increased 2.4-fold (Fig. 3D, right panel; Table 1). In La3+, the initial rate was hardly affected by FPL (0.015 versus 0.017 spikes/cell) (Fig. 3F, right, upper panel), whereas the sustained rate was 2.1-fold faster in the presence of FPL (Fig. 3F, right, lower panel).

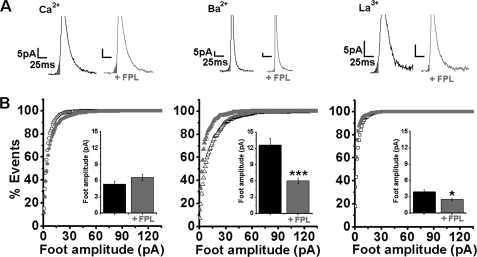

Effect of FPL on Spike and Foot Kinetics

The spike parameters, peak amplitude, half-width, rise time of 50–90%, and mean charge were barely affected in Ca2+, Ba2+, or La3+ as charge carriers (supplemental Table SI).

Because the kinetics of the fusion pore are affected by the charge carriers (33), we examined foot kinetics modulation by FPL switching Ca2+ for Ba2+ or La3+. The foot amplitude, foot width, and the mean charge of foot events, which revealed significantly ranging differences when substituting Ba2+ or La3+ for Ca2+ (33), were further modified by FPL (Fig. 4; supplemental Table SII). Although in Ca2+ the foot parameters were not significantly affected, the foot amplitude, foot width, foot charge, and time constant of fusion pore opening (τfp) were significantly lower when Ba2+ was the charge carrier (Fig. 4B and supplemental Fig. SIIB). In La3+, FPL lowered foot amplitude (Fig. 4B) but did not affect foot width or τfp (supplemental Fig. SIIC; supplemental Table SII).

FIGURE 4.

FPL modifies foot amplitude in single chromaffin cells in Ca2+, Ba2+, or La3+. Amperometric currents were triggered by a 30-s pulse of K60 from single cells in solutions of 2 mm Ca2+, 2 mm Ba2+, or 0.2 mm La3+ with or without 0.5 μm FPL. A, representative foot in Ca2+, Ba2+, or La3+ elicited with and without 0.5 μm FPL; bars are as indicated. B, cumulative distribution plot of foot events and analysis of foot amplitude. Insets, mean values of foot amplitude with or without 0.5 μm FPL, see supplemental Table SII. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001. The number of foot amplitudes analyzed is given in supplemental Table SII.

BayK and FPL Increase Ca2+ and Ba2+ Influx

Ca2+ influx in bovine chromaffin cells is mediated primarily (∼70%) via the N- and P/Q-type channels (52, 53); hence, the net contribution of BayK and FPL to Ca2+ entry via the L-type (Cav1.2) is ∼30%, and the augmentation by the L-channel agonists in the high background of the other channels is more difficult to quantify. Nonetheless, both BayK and FPL, similar to other cells that express L-type channels, augment Ca2+ influx in bovine chromaffin cells as reported previously (26, 28, 29, 54, 55).

FPL Increases the Rate of Secretion by Modifying the Channel

To further explore whether the FPL-enhanced rate of secretion was independent of ion flux, we used a Ca2+-impermeable Cav1.2 channel.

Chromaffin cells were infected with Semliki Forest virus containing either WT α11.2 or the mutated α11.2/L775P subunit (40). The single point mutation L775P renders the channel impermeable to Ca2+ (41) but does not affect its voltage sensitivity or the Ca2+ binding at the pore (40). Introduction of another single point mutation T1066Y (11) renders the channels insensitive to nifedipine and allows detection of secretion mediated by the infected channel when the endogenous Cav1.2 is blocked by nifedipine.

Bovine chromaffin cells were infected with the nifedipine-insensitive wild type α11.2 or the nonconducting α11.2/L775P subunit and stimulated to release by K60 with or without FPL in the presence of 5 μm nifedipine (31, 40). Under these conditions, the amperometric currents were mediated mainly by the virus-infected channels, because secretion mediated by the endogenous channels was ∼90% blocked (see Fig. 1A, inset) (31, 40). Previously, we have shown that spike parameters mediated by α11.2/L775P were similar to WT α11.2 subunit (40).

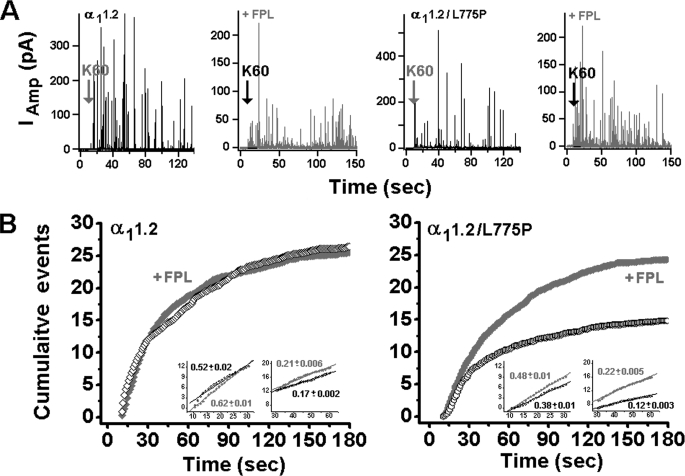

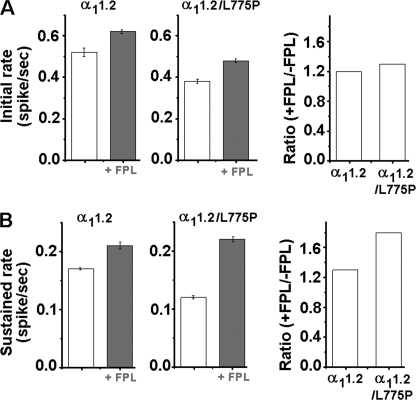

The overall time course of secretion in cells infected with α11.2 and α11.2/L775P was determined from normalized waiting time distributions constructed by spike counting (Fig. 5A). The two-phase slope observed corresponded to the initial rate (10–30 s) and the sustained rate (30–60 s). The initial rate was increased 1.2-fold by FPL in WT α11.2-infected cells (Fig. 5B, left panel, inset, and Fig. 6 A, right panel) and 1.3-fold in α11.2/L775P-infected cells (Fig. 5B, right panel, inset, and Fig. 6A, right panel), and the apparent sustained rates were increased 1.3-fold in WT (Fig. 5B, left panel, inset, and Fig. 6A, right panel) and 1.8-fold in the mutated channel (Fig. 5B, right panel, inset, Fig. 6B, right panel, and Table 2). The similar increase in spike frequency induced by FPL in cells infected with either WT or the impermeable channel, which is also similar to the fold increase observed in noninfected cells (Table 1), suggested that there was no involvement of Cav1.2-mediated Ca2+ influx in triggering secretion.

FIGURE 5.

FPL affects depolarization-evoked release mediated in cells infected with the mutated Cav1.2 channel subunit pSFV α11.2/L775P. A, amperometric currents were triggered by a 10-s pulse of K60 from single cells infected with either α11.2 subunit or the impermeable α11.2/L775P with 2 mm Ca2+ as the charge carrier, with or without 0.5 μm FPL and in the presence of 5 μm nifedipine. B, cumulative distribution of spikes plotted versus time after the onset of K60 depolarization in cells infected with WT α11.2 subunit (left panel) and the mutated α11.2/L775P subunit (right panel) in the presence (●, ♦) and in the absence of 0.5 μm FPL (○, ◇), respectively. Inset, expanded scale of the cumulative events elicited by a 10-s pulse of K60 from single cells infected with either α11.2 Cav1.2 subunit (left panel) or the impermeable α11.2/L775P (right panel) with 2 mm Ca2+ as the charge carrier, emphasizing the initial rates (10–30 s) and sustained rates (30–60 s).

FIGURE 6.

Initial and sustained rates of secretion mediated by α11.2 and α11.2/L775P are elevated to a similar extent by FPL. Initial (10–30 s) (A) and sustained (60–180 s) (B) slopes of the corresponding cumulative spike plot (see “Experimental Procedures”) of α11.2 and α11.2/L775P in the presence and absence of FPL. The extent of FPL effect is shown by the ratio of the initial (A) and sustained rates (B) with and without FPL (right).

TABLE 2.

FPL affects the rate of secretion mediated in cells infected with the wild type pSFVα11.2 and mutated pSFVα1 1.2/L775P subunits

| Cation | Cells | Frequency (spike/s)a |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial rate (10–30 s) | Sustained rate (30–60 s) | ||||

| n | Ratio | Ratio | |||

| α11.2 | 25 | 0.52 ± 0.02 | 1.2 | 0.17 ± 0.002 | 1.3 |

| + FPLb | 25 | 0.62 ± 0.01 | 0.21 ± 0.006 | ||

| α11.2/L775P | 30 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 1.3 | 0.12 ± 0.003 | 1.8 |

| + FPL | 34 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 0.22 ± 0.005 | ||

a Cells were stimulated for 10 s by 60 mm KCl using 2 mm Ca2+.

b Cells were stimulated for 10 s by 60 mm KCl in the presence of 0.5 μm FPL.

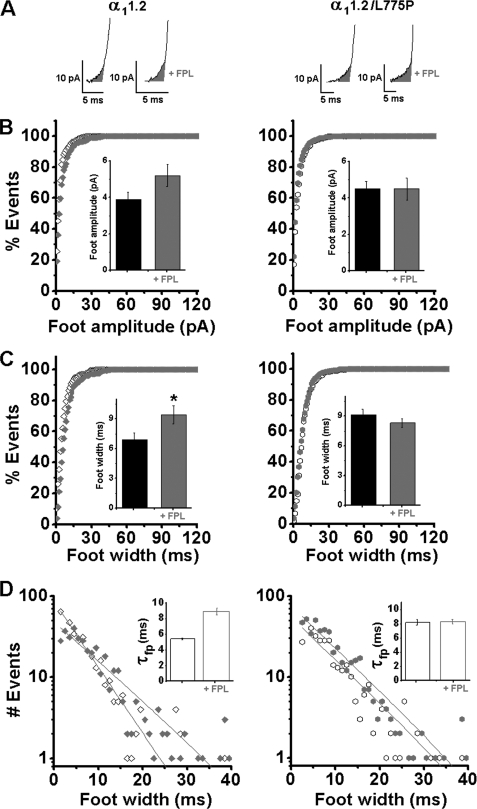

Effect of FPL on Spike and Foot Parameters in Infected Cells

To substantiate the idea that conformational changes in the Ca2+ channel can directly participate in the formation or configuration of the fusion pore without calcium entry, we tested the effects of FPL on spike and foot properties induced via the impermeable channel.

The modulation of WT α11.2 and α11.2/L775P mutant by FPL displayed no significant difference in spike parameters, as shown in supplemental Table SIII. Several significant changes were observed in foot parameters of the WT channel (Fig. 7; supplemental Table SIV). Analysis of foot kinetics (see representative individual recordings, Fig. 7A) showed that although foot amplitude in the WT channel rose from 3.9 ± 0.4 to 5.2 ± 0.6 pA, it was not modified in the α11.2/L775P mutant (Fig. 7B). Also foot width (Fig. 7C) and the mean open time of the fusion pore (τfp; Fig. 7D) were increased in WT α11.2, and not in the α11.2/L775P mutant (supplemental Table SIV).

FIGURE 7.

Effect of FPL on release mediated by a Ca2+-impermeable channel. Amperometric currents were triggered by a 10-s pulse of K60 from single cells infected with either WT α11.2 subunit (left) or the impermeable α11.2/L775P (right) with 2 mm Ca2+ as the charge carrier, with or without 0.5 μm FPL and in the presence of 5 μm nifedipine. A, representative foot traces of single vesicle release events. B, cumulative distribution of foot events mediated by α11.2 WT subunit (left panel) and α11.2/L775P (right panel) plotted versus time after the onset of K60 depolarization. Inset, analysis of foot amplitude, mean values for foot amplitude events (see supplemental Table SIV). C, cumulative distribution of foot events mediated by α11.2 WT subunit (left panel) and α11.2L/775P (right panel) plotted versus time after the onset of K60 depolarization; inset, analysis of foot width. D, single exponential fits to time distributions yielded the mean fusion pore open time (τfp, left panel); inset, τfp values (right panel). *, p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The physical and functional interactions of Cav1.2 with the exocytotic machinery have led us to suggest that Cav1.2 constitutes an integral part of the exocytotic machinery (30, 32, 34–36, 38, 56–58). Substantiation of our proposed model has come from two major lines of evidence showing the following: 1) La3+ through binding to the selectivity filter of the channel could support secretion without cell entry (31, 33, 39), and 2) depolarization of cells in which the α11.2 subunit was replaced by a Ca2+-impermeant α11.2/L775P mutant could trigger release when expressed in chromaffin cells (40). Based on these studies, we proposed that the channel could act as a signaling switch by binding Ca2+ at the pore of the channel prior to a rise in [Ca2+]i (40).

In this study, the direct involvement of the channel in secretion was tested further by examining BayK and FPL, which through binding to the α11.2 subunit modify the channel kinetics and evoke a large cation influx. The effects of BayK and FPL on the kinetics of secretion using permeable cations were compared under conditions in which ion permeation is virtually negligible.

Effects of BayK and FPL on the Rate of Secretion

Bovine chromaffin cells in which secretion is mediated almost exclusively via Cav1.2 (45) was employed to distinguish between Cav1.2 as the signaling trigger of secretion, from its role as an ion transport protein (45). In this system, we showed that BayK binding to Cav1.2 increased both the initial and the sustained rates of secretion, using the charge carriers Ca2+, Ba2+, or La3+. An increase in Ca2+ or Ba2+ influx has been proposed to explain the augmentation of the rate of secretion. However, these reagents enhanced the rate of secretion to a similar extent when the nonconducted La3+ ion replaced Ca2+ (Table 1). This result indicates that the rate of secretion was affected by BayK or FPL prior to and independent of ion flux, most likely by conferring a structural change upon the channel, upstream to Ca2+ entry.

Secretion has previously been shown to be mediated by releasing a competent excitosome complex assembled by VGCC and synaptic proteins (32, 34–36, 38, 39, 56–61). The frequent channel opening induced by BayK and FPL (17, 18) implies potentially more interactive channels, frequent encounters of the channel with synaptic proteins, and generation of more competent releasing complexes (35, 36, 38, 57, 60, 61). Therefore, the increase in the frequency of channel opening by BayK and FPL could have accounted in part for the increase in the rate of secretion observed in all the cations. This result also indicates potential involvement of the channel itself in the release, because La3+, which binds and occupies the pore of the channel, is excluded from entry to the cell.

Modulation of single channels underlying hippocampal L-type current enhancement by BayK and FPL is also dependent on the type of ion bound at the selectivity filter (Ref. 17 and also see Ref. 50). The functional reciprocity between BayK site of interaction and the binding site for Ca2+, Ba2+, or La3+ at the permeation pore (1) was demonstrated by the differences in the rates of secretion seen with BayK in the presence of each of these ions.

FPL Enhances the Rate of Secretion Mediated by the Ca2+-impermeable Channel α11.2/L775P

To further examine the effect of FPL on secretion and to dissect the kinetic changes from the sizeable Ca2+ influx associated with FPL binding to the channel, we used the Ca2+-impermeable mutant α11.2/L775P, which by virtue of a second mutation, T1066Y, is nifedipine-insensitive (40). It is worth mentioning that because both BayK and nifedipine are members of the dihydropyridine family and bind to the same site at the channel, the mutated L775P/T1066Y-impermeable channel is also BayK-insensitive. Therefore, the effect of BayK on the impermeable mutated channel was not feasible.

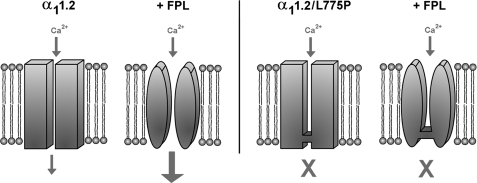

The increase in the rate of secretion induced by FPL in cells infected with either WT α11.2, α11.2/L775P, or noninfected cells was similar. It clearly demonstrates that the enhanced secretion is Ca2+ influx-independent. These results support a model in which conformational changes induced by FPL are conveyed from the channel to the release machinery to enhance secretion (Fig. 8). By inference, the persistent effect of BayK and FPL in La3+, which is similar to Ca2+ and Ba2+, or the interaction of FPL with the impermeable Cav1.2 could be caused by a structural change at the channel rather than Ca2+ influx.

FIGURE 8.

Schematic view of FPL-modified α11.2 subunit. The binding of FPL to the α11.2 subunit of the channel modified the channel properties and increased Ca2+ entry (left panel). The α11.2/L775P subunit is similarly modified by FPL but does not conduct Ca2+ (right panel). The similar modulation of secretion by the WT α11.2 and the mutated channel α11.2/L775P suggests the involvement of structural changes induced by FPL during voltage perturbation and the subsequent calcium ion occupancy of the selectivity filter prior to Ca2+ influx (40).

We have previously proposed that the transition of the channel from a nonconducting to a conducting mode could be the trigger of secretion (30, 33, 39, 40). Consistent with this proposition, FPL causes a transition in the channel kinetics, from a nonconducting inactivated state to a conducting state (62), thus contributing to the enhanced rate of catecholamine secretion seen prior to Ca2+ influx.

The binding of both FPL and BayK to the channel increases the rate of secretion, indicating that the channel is coupled to the exocytotic machinery. In the future, it would be interesting to explore interactions of the ligand-bound channel with the individual synaptic proteins, similar to previous studies using heterologous expression systems.

Channel Agonists Affect Foot Parameters

Synaptic vesicles fuse with the cell membrane via a fusion pore, an aqueous opening that spans both plasma and vesicle membranes. The initial opening of fusion pores of catecholamine-containing vesicles can be detected as pre-spike foot signals prior to the full dilation of the pore (42). Previous analysis of foot parameters showed that the type of cations residing at the selectivity filter can influence the size and stability of the fusion pore (31, 33). Combined with the evidence that the type of permeating ions also differentially affects the coupling of the channel with syntaxin (63), it was proposed that the Ca2+ channel could directly participate in the configuration of the fusion pore (31). This is consistent with the vesicle fusion model that promotes a proteinaceous fusion pore in which the pore is generated by the association of proteins from the vesicular and plasma membranes (43, 64). The fusion pore kinetics, which is differently modified by BayK and FPL depending on the type of the charge carrier, substantiated the likely involvement of the channel in the configuration of the fusion pore.

Modifications of the fusion pore by BayK or FPL could occur either by means of a direct effect on the fusion pore or indirectly through the interaction with the channel, which is one of the proteins that constitutes the fusion pore structure. Whereas direct effect of BayK or FPL on the fusion pore is quite unlikely because of their high specificity for the channel, they could affect it indirectly, through binding to the channel. The latter possibility substantiates previous results suggesting that the channel could be a constituent of the fusion pore (31, 33, 40). Furthermore, the idea that conformational changes in the Ca2+ channel can directly participate in the formation or configuration of the fusion pore was further explored by FPL applied to cells infected with WT channel subunit α11.2 or impermeable α11.2/L775P mutant.

Modulation of foot parameters by FPL was observed in cells infected with the WT channel. In contrast, the mutated Ca2+-impermeable channel, which further substantiated the increase in the rate similar to La3+ as the charge carrier, showed no changes in the foot parameters. The lack of changes in the fusion pore parameters induced by FPL in the mutated channel could imply that calcium entry is required for FPL-mediated effects on foot properties. However, because foot parameters were modified in La3+ in the absence of Ca2+ entry, the possibility of an effect on fusion pore by Ca2+ from the inside is less probable. Another interpretation would be that the conformation of the mutated channel was such that bound FPL led to no further changes in the fusion pore parameters or that the changes were too small to be detected by amperometry.

It is therefore appealing to conjecture that different conformations of the channel may give rise to distinct properties of the fusion pores, supporting the view that the VGCC could participate in the configuration of the fusion pore. These results are consistent with the effects of BayK and FPL on secretion, which occur upstream to cation influx, and support the model in which the opening of a fusion pore is viewed as a conformational transition of a proteinaceous complex consisting of the VGCC.

Taken together, we have demonstrated that the enhanced rate of catecholamine secretion in chromaffin cells with Ca2+, Ba2+, or La3+ is independent of the profound impact of BayK and FPL on cation influx through Cav1.2. These results are consistent with the view that the channel plays a pivotal role in initiating and regulating evoked secretion. They substantiate the model in which the channel is acting not only as a voltage sensor and a Ca2+-conducting protein but also as a cell-signaling switch that triggers secretion by a conformational change prior to and independent of ion transport into the cell.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. M. Trus for editing the manuscript.

This work was supported by an operating grant (to D. A.) from The Betty Feffer Fund, H. L. Lauterbach, and The Zentner Fund.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. SI and SII and Tables SI–SIV.

- VGCC

- voltage-gated Ca2+ channel

- BayK 8644

- 1,4-dihydro-2,6-dimethyl-5-nitro-4-[2(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]pyridine-3- carboxylic acid methyl ester

- FPL64176

- (FPL) 2,5-dimethyl-4-[2-(phenylmethyl)benzoyl]-1H-pyrrole-3-carboxylic acid methyl ester

- WT

- wild type.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peterson B. Z., Catterall W. A. (2006) Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 667–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hess P., Lansman J. B., Tsien R. W. (1984) Nature 311, 538–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kokubun S., Reuter H. (1984) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 81, 4824–4827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baxter A. J., Dixon J., Ince F., Manners C. N., Teague S. J. (1993) J. Med. Chem. 36, 2739–2744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peterson B. Z., Catterall W. A. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 18201–18204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peterson B. Z., Tanada T. N., Catterall W. A. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 5293–5296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herzig S. (1996) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 295, 113–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Striessnig J., Grabner M., Mitterdorfer J., Hering S., Sinnegger M. J., Glossmann H. (1998) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 19, 108–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huber I., Wappl E., Herzog A., Mitterdorfer J., Glossmann H., Langer T., Striessnig J. (2000) Biochem. J. 347, 829–836 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng W., Rampe D., Triggle D. J. (1991) Mol. Pharmacol. 40, 734–741 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He M., Bodi I., Mikala G., Schwartz A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 2629–2633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catterall W. A. (1999) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 868, 144–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lauven M., Handrock R., Müller A., Hofmann F., Herzig S. (1999) Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 360, 122–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamaguchi S., Okamura Y., Nagao T., Adachi-Akahane S. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 41504–41511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marrion N. V., Tavalin S. J. (1998) Nature 395, 900–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu L., Gonzalez P. K., Barrett C. F., Rittenhouse A. R. (2003) Neuropharmacology 45, 281–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tavalin S. J., Shepherd D., Cloues R. K., Bowden S. E., Marrion N. V. (2004) J. Neurophysiol. 92, 824–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cloues R. K., Tavalin S. J., Marrion N. V. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 6493–6503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher R. E., Gray R., Johnston D. (1990) J. Neurophysiol. 64, 91–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kavalali E. T., Plummer M. R. (1996) J. Neurosci. 16, 1072–1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hui K., Gardzinski P., Sun H. S., Backx P. H., Feng Z. P. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 338, 783–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Usowicz M. M., Gigg M., Jones L. M., Cheung C. W., Hartley S. A. (1995) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 275, 638–645 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rampe D., Lacerda A. E. (1991) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 259, 982–987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan J., Yuan Y., Palade P. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 280, C565–C572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunze D. L., Rampe D. (1992) Mol. Pharmacol. 42, 666–670 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.García A. G., Sala F., Reig J. A., Viniegra S., Frías J., Fontériz R., Gandía L. (1984) Nature 309, 69–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bossu J. L., De Waard M., Feltz A. (1991) J. Physiol. 437, 603–620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montiel C., de la Fuente M. T., Vinet R., del Valle M., Gandía L., Artalejo A. R., García A. G. (1994) Eur. J. Pharmacol. 268, 293–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cano-Abad M. F., Villarroya M., García A. G., Gabilan N. H., López M. G. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39695–39704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atlas D. (2001) J. Neurochem. 77, 972–985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lerner I., Trus M., Cohen R., Yizhar O., Nussinovitch I., Atlas D. (2006) J. Neurochem. 97, 116–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trus M., Wiser O., Goodnough M. C., Atlas D. (2001) Neuroscience 104, 599–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marom M., Sebag A., Atlas D. (2007) Channels 1, 377–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wiser O., Bennett M. K., Atlas D. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 4100–4110 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wiser O., Trus M., Hernández A., Renström E., Barg S., Rorsman P., Atlas D. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 248–253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen R., Schmitt B. M., Atlas D. (2005) Biophys. J. 89, 4364–4373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen R., Marom M., Atlas D. (2007) PLoS One 2, e1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen R., Schmitt B. M., Atlas D. (2008) Methods Mol. Biol. 440, 269–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trus M., Corkey R. F., Nesher R., Richard A. M., Deeney J. T., Corkey B. E., Atlas D. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 14461–14467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hagalili Y., Bachnoff N., Atlas D. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 13822–13830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hohaus A., Beyl S., Kudrnac M., Berjukow S., Timin E. N., Marksteiner R., Maw M. A., Hering S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38471–38477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chow R. H., von Rüden L., Neher E. (1992) Nature 356, 60–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Breckenridge L. J., Almers W. (1987) Nature 328, 814–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang C. T., Grishanin R., Earles C. A., Chang P. Y., Martin T. F., Chapman E. R., Jackson M. B. (2001) Science 294, 1111–1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ceña V., Nicolas G. P., Sanchez-Garcia P., Kirpekar S. M., Garcia A. G. (1983) Neuroscience 10, 1455–1462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wightman R. M., Jankowski J. A., Kennedy R. T., Kawagoe K. T., Schroeder T. J., Leszczyszyn D. J., Near J. A., Diliberto E. J., Jr., Viveros O. H. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88, 10754–10758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leszczyszyn D. J., Jankowski J. A., Viveros O. H., Diliberto E. J., Jr., Near J. A., Wightman R. M. (1991) J. Neurochem. 56, 1855–1863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Colliver T. L., Hess E. J., Pothos E. N., Sulzer D., Ewing A. G. (2000) J. Neurochem. 74, 1086–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.von Rüden L., Neher E. (1993) Science 262, 1061–1065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodríguez-Contreras A., Yamoah E. N. (2003) Biophys. J. 84, 3457–3469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lacerda A. E., Kim H. S., Ruth P., Perez-Reyes E., Flockerzi V., Hofmann F., Birnbaumer L., Brown A. M. (1991) Nature 352, 527–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Artalejo C. R., Adams M. E., Fox A. P. (1994) Nature 367, 72–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.García-Palomero E., Renart J., Andrés-Mateos E., Solís-Garrido L. M., Matute C., Herrero C. J., García A. G., Montiel C. (2001) Neuroendocrinology 74, 251–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Borges R., Machado J. D., Betancor G., Camacho M. (2002) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 971, 184–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rosa J. M., Gandia L., Garcia A. G. (2009) Pflugers Arch. 458, 795–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wiser O., Tobi D., Trus M., Atlas D. (1997) FEBS Lett. 404, 203–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Arien H., Wiser O., Arkin I. T., Leonov H., Atlas D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 29231–29239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cohen R., Elferink L. A., Atlas D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 9258–9266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Leung Y. M., Kwan E. P., Ng B., Kang Y., Gaisano H. Y. (2007) Endocr. Rev. 28, 653–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tobi D., Wiser O., Trus M., Atlas D. (1998) Receptors Channels 6, 89–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Atlas D., Wiser O., Trus M. (2001) Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 21, 717–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McDonough S. I., Mori Y., Bean B. P. (2005) Biophys. J. 88, 211–223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wiser O., Cohen R., Atlas D. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 3968–3973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jackson M. B., Chapman E. R. (2008) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 684–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.