Abstract

The pathogen Mycobacterium tuberculosis produces a burst of cAMP upon infection of macrophages. Bacterial cyclic AMP receptor proteins (CRP) are transcription factors that respond to cAMP by binding at target promoters when cAMP concentrations increase. Rv3676 (CRPMt) is a CRP family protein that regulates expression of genes (rpfA and whiB1) that are potentially involved in M. tuberculosis persistence and/or emergence from the dormant state. Here, the CRPMt homodimer is shown to bind two molecules of cAMP (one per protomer) at noninteracting sites. Furthermore, cAMP binding by CRPMt was relatively weak, entropy driven, and resulted in a relatively small enhancement in DNA binding. Tandem CRPMt-binding sites (CRP1 at −58.5 and CRP2 at −37.5) were identified at the whiB1 promoter (PwhiB1). In vitro transcription reactions showed that CRP1 is an activating site and that CRP2, which was only occupied in the presence of cAMP or at high CRPMt concentrations in the absence of cAMP, is a repressing site. Binding of CRPMt to CRP1 was not essential for open complex formation but was required for transcription activation. Thus, these data suggest that binding of CRPMt to the PwhiB1 CRP1 site activates transcription at a step after open complex formation. In contrast, high cAMP concentrations allowed occupation of both CRP1 and CRP2 sites, resulting in inhibition of open complex formation. Thus, M. tuberculosis CRP has evolved several distinct characteristics, compared with the Escherichia coli CRP paradigm, to allow it to regulate gene expression against a background of high concentrations of cAMP.

Keywords: Gene/Regulation, Signal Transduction/Adenylate Cyclase, Signal Transduction/Cyclic Nucleotides/Cyclic AMP, Transcription/Bacteria, Transcription/Promoter, Transcription/Regulation

Introduction

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is one of the most successful human pathogens, contributing to the deaths of ∼2 million people per annum by causing tuberculosis (1). It is an adaptable bacterium capable of survival in its preferred environment, the interior of a macrophage (2), and within droplet nuclei in the atmosphere that are produced by infected individuals. The disease is spread by inhalation of such droplets, and following initial infection, M. tuberculosis can persist in a nonreplicating state from which it may emerge when conditions are more favorable (e.g. when the immune system is suppressed), a phenomenon known as reactivation tuberculosis (3). This strategy has been so successful that the reservoir of infection is thought to be as great as one-third of the world's population (1), and thus the potential for reactivation tuberculosis is very large.

Appropriate gene regulation is likely to be vital for establishing and emerging from the dormant state. The presence of >100 regulator proteins, 11 two-component systems, 6 serine-threonine protein kinases, and 13 alternative σ factors (4) suggests that transcription regulation is important for M. tuberculosis pathogenesis. Cyclic AMP is likely to be an important signaling molecule in M. tuberculosis because it is predicted to possess 17 genes encoding adenylyl cyclases (4), at least one of which, Rv0386, is required for virulence (5). Interestingly, cAMP levels increase upon infection of macrophages by pathogenic mycobacteria (6, 7), and furthermore, addition of cAMP to cultures of M. tuberculosis causes changes in gene expression (8). Recently, Bishai and co-workers (5) showed that upon infection of macrophages, a bacterially derived cAMP burst promotes bacterial survival by interfering with host signaling pathways, but as well as influencing host regulatory networks, cAMP is also important in bacterial gene regulation.

The best characterized bacterial cAMP-responsive transcriptional regulator is the Escherichia coli cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP,2 sometimes known as catabolite gene activator protein). E. coli CRP is activated by binding cAMP and controls aspects of carbon metabolism and virulence gene expression and may act as a more general chromosome organizer (9–11). In E. coli under conditions of glucose starvation, intracellular cAMP concentrations increase via a mechanism involving interactions between the glucose phosphotransferase system transporter and adenylyl cyclase (12). Cyclic AMP is bound by the E. coli CRP dimer resulting in enhanced recognition of a specific DNA sequence (TGTGANNNNNNTCACA) present within the promoter regions of target genes (13). At activated promoters, CRP recruits RNA polymerase (RNAP) and promotes transcription by establishing specific protein-protein contacts (10, 14).

The M. tuberculosis Rv3676 protein (hereafter CRPMt) is a member of the CRP family (15–17). CRPMt is 32% identical (53% similar) over 189 amino acids to E. coli CRP (16). Like CRP in E. coli, CRPMt is a global transcriptional regulator because a deletion mutant has altered transcription of a large number of genes (16). Moreover, it is implicated in the virulence of M. tuberculosis because the CRPMt mutant is attenuated for growth in mice and macrophages as well as in vitro (16). Polymorphisms in CRP that enhance DNA binding have also occurred in the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccine strain of Mycobacterium bovis (18–20) and result in changes in transcription of a number of genes, which, although not contributing to the attenuation of Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, may have been selected by growth in vitro (20).

In the CRPMt mutant, the largest decreases in expression were for the rpfA and whiB1 genes (16). In vivo and in vitro analyses indicated that CRPMt activates expression of rpfA and whiB1 (16, 17). These are potentially significant observations because rpfA encodes a protein that is thought to be involved in reviving dormant bacteria (21), and whiB1 encodes a Wbl family protein (22). Wbl proteins are found only in actinomycetes and bind redox-sensitive iron-sulfur clusters (23, 24). The mechanism(s) of action of Wbl proteins is still unclear; some have been reported to have protein-disulfide reductase activity (24), and at least one (WhiB3) has been shown to bind DNA (25), consistent with the suggestion that Wbl proteins are transcription factors that might function in the control of developmental processes (22, 26). This latter suggestion raises the possibility that CRPMt in complex with cAMP regulates genes involved in the developmental switch associated with M. tuberculosis persistence and/or emergence from the dormant state. However, previous work suggested that although CRPMt binds cAMP, this interaction induces a relatively small enhancement in specific DNA binding (15–17). Thus, there are differences between E. coli CRP, where the presence of cAMP enhances specific DNA binding by several orders of magnitude (27), and CRPMt. Hence, the aim of this work was to investigate the interaction between CRPMt and cAMP and determine the mechanism of CRPMt-mediated activation of whiB1 expression. Here, the following points are shown: (i) CRPMt dimer binds two molecules of cAMP; (ii) unlike E. coli CRP, the CRPMt cAMP-binding sites do not interact; (iii) CRPMt binds at two immediately adjacent sites in the whiB1 promoter; and (iv) occupation of the upstream CRPMt-binding site at low cAMP concentrations activates whiB1 transcription at a step after open complex formation, whereas occupation of the downstream site at high cAMP concentrations antagonizes activation from the upstream site by preventing open complex formation. In addition, a molecular model based on the E. coli CRP structure provides a plausible explanation for the distinctive cAMP binding properties of CRPMt.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions

Bacterial strains and plasmids are listed in Table 1. E. coli cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (36) in a 1:5 volume/flask ratio at 37 °C with shaking at 250 rpm, except for in vivo transcription experiments where strains were grown in a 1:25 volume/flask ratio. Where required, antibiotics were added to media at the following concentrations: tetracycline 35 μg ml−1, kanamycin 50 μg ml−1, ampicillin 100 μg ml−1. M. tuberculosis cultures (100 ml) were grown in 1 liter of polycarbonate culture bottles (Techmate) in a Bellco roll-in incubator (2 rpm) at 37 °C in Dubos broth containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 80 supplemented with 0.2% (v/v) glycerol and 4% Dubos medium albumin. Where required, kanamycin was added at a final concentration of 25 μg ml−1. Mycobacterium smegmatis was grown to log phase (56 h) in LB medium in a 1:5 volume/flask ratio at 37 °C with shaking at 250 rpm.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

IPTG is isopropyl 1-thio-β -d-galactopyranoside.

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| BL21 (λDE3) | Lysogen of λDE3 carrying a copy of the T7 RNAP under the control of the IPTG-inducible lacUV5 promoter | Novagen |

| JRG5876 | BL21 (λDE3) ΔcyaA; kanR | This work |

| JRG6015 | JRG5876 pGS2132 | This work |

| M182 | E. coli K12 Δlac | 28 |

| JRG2630 | M182 Δ crp derivative | 29 |

| JRG5875 | M182 ΔcrpΔcyaA | This work |

| JRG6016 | JRG2630 p2130 ptac85 | This work |

| JRG6017 | JRG2630 p2130 pGS1645 | This work |

| JRG6018 | JRG5875 p2130 ptac85 | This work |

| JRG6019 | JRG5875 p2130 pGS1645 | This work |

| M. tuberculosis strains | ||

| H37Rv | Wild-type virulent strain | 30 |

| ΔRv3676 | H37Rv, deletion of Rv3676 (CRPMt) | 16 |

| H37Rv/pRB142 | H37Rv, with whiB1-lacZ reporter plasmid pRB142 | This work |

| H37Rv/pRB143 | H37Rv, with whiB1-lacZreporter plasmid pRB143 | This work |

| H37Rv/pRB144 | H37Rv, with whiB1-lacZ reporter plasmid pRB144 | This work |

| H37Rv/pRB145 | H37Rv, with whiB1-lacZ reporter plasmid pRB145 | This work |

| H37Rv/pRB146 | H37Rv, with whiB1-lacZ reporter plasmid pRB146 | This work |

| ΔRv3676/pRB142 | ΔRv3676, with whiB1-lacZreporter plasmid pRB142 | This work |

| M. smegmatisstrains | ||

| mc2 155 | Source of RNAP | 31 |

| E. coli plasmids | ||

| pCR4Blunt-TOPO | General cloning vector for blunt-ended PCR products; ApR, KanR | Invitrogen |

| pET28a | His6 tag overexpression vector; KanR | Novagen |

| pRW50 | lacZ transcriptional reporter plasmid; TetR | 32 |

| ptac85 | Expression vector with an IPTG-inducible promoter; ApR | 33 |

| pGS1645 | ptac85 containing Rv3676 gene | This work |

| pGS2060 | pCR4Blunt-TOPO containing the region upstream of whiB1 | This work |

| p2130 | pRW50 containing CCgalΔ4, a derivative of galP1 with a consensus CRP-binding site centered at position −37.5 bp | 34 |

| pGS2132 | pET28a derivative encoding His6-CRPMt fusion protein; ApR | This work |

| pGS2060 | pCR4Blunt-TOPO containing the 285-bp region upstream of whiB1 | This work |

| pGS2061 | As pGS2060 but with CRPMt site 1 altered to AGTTAGATAGCCAACG | This work |

| p2225 | As pGS2060 but with CRPMt site 2 altered to CCAAACACTATTGACA | This work |

| p2227 | As pGS2060 but with CRPMt site 1 and site 2 altered | This work |

| M. tuberculosisshuttle plasmids | ||

| pEJ414 | lacZ transcriptional reporter plasmid; KanR | E. O. Davis (35) |

| pRB142 | pEJ414 derivative containing transcriptional fusion of whiB1 upstream region with lacZ | This work |

| pRB143 | pRB142 with mutated CRP1 | This work |

| pRB144 | pRB142 with mutated CRP2 | This work |

| pRB145 | pRB142 with mutated CRP1 and CRP2 | This work |

| pRB146 | pRB142 with improved CRP2 | This work |

Overproduction and Purification of CRPMt

The CRPMt (Rv3676) open reading frame was amplified by PCR using primers Myc1746 (5′-CATCATGAATTCGTGGACGAGATCCTGGCC-3′) and Myc1747 (5′-CATCATACTCGAGCACTATTACCTCGCTCGGCGGGC-3′) containing engineered EcoRI and XhoI sites, respectively. This fragment was ligated into the corresponding sites of a pET28a derivative, in which the kanamycin resistance gene had been disrupted by the insertion of an ampicillin resistance gene (bla). The resulting plasmid (pGS2132) encoded a His6-CRPMt fusion protein. The plasmid pGS2132 was moved into E. coli strain JRG5876 (BL21 λDE3 ΔcyaA), for expression of the recombinant protein by addition of 1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, followed by a further 3-h growth at 37 °C before collecting the bacteria by centrifugation. The bacteria were lysed by resuspending in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.2, containing 0.5 m NaCl, followed by repeated freeze-thawing and sonication. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation, and the resulting cell-free extract was passed through a nickel-charged Hi-Trap chelating column (GE Healthcare). The recombinant His6-CRPMt protein was eluted using an imidazole gradient (0–500 mm in 20 ml). The pooled fractions containing His6-CRPMt were dialyzed in phosphate-buffered saline (137 mm NaCl, 2.7 mm KCl, 10 mm Na2HPO4, 2 mm KH2PO4), and 10% (v/v) glycerol was added to the protein before storage at −20 °C. Where indicated the His6 tag was removed by treatment with the protease thrombin (10 units for 16 h at 4 °C).

Trypsin Digestion of His6-CRPMt

Recombinant His6-CRPMt (15 μg) was incubated with 2 mm cAMP or cGMP for 10 min at 37 °C, followed by the addition of a second cyclic nucleotide (2 mm) for 10 min where indicated. The protein was then cleaved with 1 μg of trypsin (Sigma) for up to 10 min at 20 °C, and the reaction was stopped by the addition of 1.3% SDS and heating to 100 °C for 10 min. The resulting fragments were analyzed on a 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel.

Isothermal Calorimetry

Recombinant His6-CRPMt was extensively dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline, and the concentration of protein was determined by SDS-PAGE and amino acid analysis (ion exchange chromatography and ninhydrin detection). The sodium salt of cAMP was dissolved in the dialysate phosphate-buffered saline, and the concentration was determined by UV absorption spectroscopy using the extinction coefficient of ϵ260 of 1.23 × 104 m−1 cm−1. All samples were centrifuged prior to the titrations. The titration calorimetry measurements were performed using a MicroCal VP-ITC (MicroCal LLC, Northampton, MA). The isothermal calorimetry sample cell (cell volume 1.4 ml) was loaded with 84 μm His6-CRPMt. After a suitable period of thermal equilibration (25 °C), 18 injections of 15 μl of 0.87 mm cAMP were introduced into the protein solution every 6 min with continual stirring and an initial delay of 2 min. A small preinjection of 3 μl was also made to expel any air bubbles that may have accumulated during equilibration. In a separate control experiment, aliquots of the cAMP solution were titrated into the dialysis buffer to determine whether the ligand exhibited heat of dilution. Data analysis and fitting were done using Origin 7.0 (MicroCal LLC), and corrected binding isotherms were best fit using a single set of identical binding sites model as described by Wiseman et al. (37).

Transfer of Plasmids, Preparation of Cell-free Extracts, and Assay for β-Galactosidase in M. tuberculosis

These were carried out as described previously (16). β-Galactosidase assays on log phase cultures (A600 nm ∼ 0.5) were done according to Miller (38). Three independent cultures were analyzed for each strain.

5′-Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends

5′-Rapid amplification of cDNA ends was performed using the 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends system from Invitrogen according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA-free RNA (5 μg) from M. tuberculosis H37Rv was reverse-transcribed with GSP1 (5′-TACGGGCTTTCGTGCG-3′) using Superscript II reverse transcriptase. The cDNA was purified on a SNAP column and tailed with dCTP using terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase. The tailed cDNA was amplified using Platinum® Taq with primers GSP2 (5′-CGCCGCTCGTCTTCGCTCAT-3′) and AAP (5′-GGCCACGCGTCGACTAGTACGGGIIGGGIIGGGIIG-3′). The product was visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel, and a band of ∼300 bp was excised and sequenced.

Construction of Reporter Gene Plasmids Using the Upstream Region of whiB1

The region of the DNA sequence upstream of whiB1 was generated by PCR from M. tuberculosis genomic DNA using the primer pairs Myc896 (5′-GCTCTAGAGCAAGAAAGCGGATCTG-3′) and Myc487 (5′-GCAAGCTTGCCTTGTGGCGCCAATC-3′) (bp 3,595,415–3,595,731). This fragment was ligated into the XbaI and HindIII sites of the polylinker in the lacZ transcriptional reporter plasmid pEJ414 (34) to make pRB142 (PwhiB1). This construct was verified by DNA sequencing.

Mutagenesis of CRP-binding Site in Plasmid pRB142

This was performed using the Stratagene QuikChange mutagenesis kit. To mutagenize CRP1 (AGTGAGATAGCCCACG to AGTtAGATAGCCaACG), the primers used were Myc898 (5′-AACGAGATCGCCAGAGTTAGATAGCCAACGCGCTTACGTAACAC-3′) and Myc899 (5′-GTGTTACGTAAGCGCGTTGGCTATCTAACTCTGGCGATCTCGTT-3′) to generate pRB143. To mutagenize CRP2 (CGTAACACTATTGACA to CcaAACACTATTGACA), the primers used were Myc900 (5′-TAGCCCACGCGCTTACCAAACACTATTGACATCTGTTGAGCCTG-3′) and Myc901 (5′-CAGGCTCAACAGATGTCAATAGTGTTTGGTAAGCGCGTGGGCTA-3′) to generate pRB144. To mutagenize both CRP1 and CRP2, the primers used were Myc963 (5′-CGCCAGAGTTAGATAGCCAACGCGCTTACCAAACACTATTGACATCTGTTG-3′) and Myc964 (5′-CAACAGATGTCAATAGTGTTTGGTAAGCGCGTTGGCTATCTAACTCTGGCG-3′) to generate pRB145. To improve CRP2 (CGTAACACTATTGACA to CGTgACACTATTGACA), the primers used were 5′-TAGCCCACGCGCTTACGTGACACTATTGACATCTGTTGAGCCTG-3′ and 5′-CAGGCTCAACAGATGCACATAGTGTTTGGTAAGCGCGTGGGCTA-3′. Mutagenized constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

β-Galactosidase Assays in E. coli

Assays were carried out on log phase cultures (A600 nm ∼ 0.5) according to Miller (38). Five independent cultures were analyzed for each strain.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays

The region upstream of the whiB1 gene was excised from plasmid pGS2060 using restriction enzymes XbaI and HindIII. The resulting fragment was end-labeled using 0.37 MBq of [α-32P]dGTP, dATP, and Klenow enzyme, and unincorporated radionucleotides were removed using a QIAquick PCR clean-up kit (Qiagen). Radiolabeled DNA (∼5 ng) was incubated with 0–21 μm His6-CRPMt (or CRPMt where indicated) and 0–2 mm cAMP, in the presence of 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 0.2 mm EDTA, 10 mm (NH4)2SO4, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 15 mm MgCl2, 15 mm KCl, 0.05 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin, and 0.01 unit of poly(dI-dC), for 30 min at 25 °C. The resulting complexes were then separated on 6% polyacrylamide gels buffered with 0.5× TBE (45 mm Tris borate, 1 mm EDTA).

DNase I Footprinting

Radiolabeled whiB1 promoter DNA, or whiB1 promoters with mutated CRP sites (∼100 ng), was incubated with 2.5–50 μm His6-CRPMt in the presence of 50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, and 2 mm cAMP for 30 min at 25 °C. Footprinting reactions containing RNAP were done in the presence of 40 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 75 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm EDTA, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and 250 μg ml−1 bovine serum albumin. The complexes were then digested with 1 unit of DNase I for 15–60 s at 25 °C. Reactions were stopped by the addition of 200 μl of 0.3 m sodium acetate, pH 5.2, containing 20 mm EDTA, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction. The DNA was ethanol-precipitated and resuspended in loading buffer (80% v/v formamide, 0.1% w/v SDS, 10% v/v glycerol, 8 mm EDTA, 0.1% w/v bromphenol blue, 0.1% w/v xylene cyanol) for electrophoretic fractionation on 6% polyacrylamide-urea gels and autoradiographic analysis. Maxam and Gilbert G tracks of the DNA fragments were used to provide a calibration (39).

In Vitro Transcription Reactions and Permanganate Footprinting

M. smegmatis RNAP was isolated by a method adapted from Beaucher et al. (40). A 6-g wet cell pellet of M. smegmatis mc2 155 was disrupted by passage through a French pressure cell. The lysate was then centrifuged and subjected to ammonium sulfate precipitation. The resulting cytoplasmic extract was dialyzed against RNAP buffer (50 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 10 μm ZnSO4, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm MgCl2, and 20% glycerol) containing 10 mm KCl, before loading onto a 5-ml HiTrap heparin column (GE Healthcare). Elution was achieved by applying a linear gradient of 0.01–1 m KCl in RNAP buffer, and the fractions containing RNAP, as determined by SDS-PAGE, were pooled. Dialysis and purification were repeated twice, using a 1-ml HiTrap SP HP cation exchange column followed by a 1-ml HiTrap Q HP anion exchange column (GE Healthcare). Fractions containing enriched holo-RNAP, as determined by SDS-PAGE, were desalted into RNAP buffer containing 10 mm KCl and concentrated 10-fold using a Vivaspin concentrator (molecular mass cutoff of 5 kDa; Sartorius). The resulting RNAP was then tested in in vitro transcription assays (not shown) and stored in 25% glycerol at −80 °C.

For in vitro transcription reactions, 0.1–1-kb markers were prepared using Perfect RNA Marker template mix (Novagen). A 20-μl reaction containing 0.75 μg of RNA template mix, 80 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 12 mm MgCl2, 10 mm NaCl, 10 mm dithiothreitol, 2 mm ATP, 2 mm GTP, 2 mm CTP, 0.1 mm UTP, 5 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (800 Ci mmol−1, PerkinElmer Life Sciences), 20 units of RiboLock RNase inhibitor (Fermentas), and 50 units of T7 RNAP (Novagen), was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, before storing at −20 °C. Markers from ∼2 ng of template were used for gel calibration.

The 285-bp region upstream of the whiB1 gene and the corresponding regions with the altered CRPMt-binding sites were excised from plasmids pGS2060, pGS2061, p2225, and p2227 using restriction enzymes XbaI and HindIII. These DNA fragments (0.2 pmol) were incubated for 15 min at 37 °C in a 21-μl reaction volume containing 40 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 75 mm KCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 5% glycerol, 250 μg ml−1 bovine serum albumin, 0–2 mm cAMP, 2 pmol of M. smegmatis RNAP, and 0–20 μm CRPMt. Transcription was initiated by the addition of 4 μl of a solution containing UTP at 50 μm; ATP, CTP and GTP at 1 mm; and 2.5 μCi of [α-32P]UTP (800 Ci mmol−1, PerkinElmer Life Sciences), followed by incubation for 15 min at 37 °C. Reactions were terminated by the addition of 25 μl of Stop/Loading dye solution (95% formamide, 20 mm EDTA, pH 8, 0.05% bromphenol blue, 0.05% xylene cyanol) containing 0.1–1-kb markers from ∼9.5 ng of template as a loading control. Samples (10 μl) of each reaction were loaded onto a 6% acrylamide, 1× TBE, 8 m urea gel and analyzed by autoradiography. Autoradiographs were quantified by ImageMaster software (GE Healthcare).

For permanganate footprinting, the whiB1 promoter fragment was prepared as for electrophoretic mobility shift assay, except that the opposite strand was end-labeled with [α-32P]dCTP. The resulting radiolabeled DNA (∼20 ng) was incubated at 20 °C for 5 min in a reaction containing 40 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 10 mm MgCl2, 75 mm KCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 5% glycerol, 250 μg ml−1 bovine serum albumin, 0.1 mm GTP, 0.1 mm UTP, 0–2 mm cAMP, and 0–20 μm His-tagged CRPMt. M. smegmatis RNAP (2 pmol) was added and incubation continued at 37 °C for 15 min. KMnO4 (1 mm) was added for 10 min at 37 °C, and the reactions were stopped by the addition of 200 μl of 0.3 m sodium acetate, pH 5.2, containing 20 mm EDTA, followed by phenol/chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The DNA was then incubated with 10% piperidine at 90 °C for 10 min before being vacuum-dried and resuspended in loading buffer (80% formamide, 0.1% SDS, 10% glycerol, 8 mm EDTA, 0.1% bromphenol blue, 0.1% xylene cyanol) for electrophoretic fractionation on 6% polyacrylamide-urea gels and autoradiographic analysis. A Maxam and Gilbert G track of the DNA fragment was used to provide a calibration (39).

RESULTS

Cyclic AMP Binding at Two Independent Sites Enhances CRPMt-DNA Interactions

Whereas E. coli CRP is very responsive to cAMP, exhibiting nonspecific low affinity DNA binding in the absence of cAMP (27), previous reports of the effects of cAMP on the properties of CRPMt have been equivocal. Rickman et al. (16) and Bai et al. (15) found significant binding of CRPMt to target DNA in the absence of cAMP and only marginal enhancement upon addition of up to 0.1 mm cAMP. In contrast, Agarwal et al. (17) failed to detect DNA binding in the absence of cAMP, but binding was observed in the presence of 1 mm cAMP. Others have shown that incubation with cAMP alters intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence (41) and the polypeptide profiles obtained when CRPMt is digested with trypsin (15), implying that cAMP causes conformational changes in CRPMt. To investigate further, we have isolated recombinant His6-tagged CRPMt by overproduction in a cyaA mutant of E. coli, which is unable to synthesize cAMP. This cAMP-free CRPMt protein was then used to determine the polypeptide profiles obtained after digestion of CRPMt with trypsin in the absence and presence of cAMP (Fig. 1A, lanes 2–7). In contrast to E. coli CRP, which is relatively resistant to trypsin cleavage in the absence of cAMP (42), CRPMt was readily digested by trypsin, yielding a major polypeptide of molecular mass ∼16 kDa, as estimated by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A). In the presence of cAMP, the protein was more resistant to proteolysis, and a major polypeptide of molecular mass ∼15 kDa was obtained. In the presence of cGMP, the sensitivity of CRPMt to trypsin was similar to that observed in the absence of cAMP, although a different digestion pattern, which included both major polypeptides (∼16 and ∼15 kDa) observed in the absence and presence of cAMP, was obtained suggesting that cGMP is bound by CRPMt with concomitant changes in conformation that are different from those invoked by cAMP (Fig. 1A, lanes 10–15). Significantly, addition of cAMP after preincubation with cGMP for 10 min, or vice versa, resulted in a limited proteolysis pattern identical to that obtained with cAMP alone indicating that cAMP is the preferred ligand (Fig. 1A, lanes 20–24). To ensure that the presence of the His6 tag was not influencing the interaction of CRPMt with cAMP, the His6 tag was removed by thrombin cleavage, and the partial proteolysis experiments were repeated. This showed that untagged CRPMt exhibited the same behavior as the tagged protein in the absence (supplemental Fig. S1, lanes 3 and 6) and presence (supplemental Fig. S1, lanes 4 and 7) of cAMP suggesting that the His6 tag was not affecting the gross conformational changes induced by cAMP binding. Therefore, the His6-tagged form of CRPMt was considered suitable for further ligand binding studies.

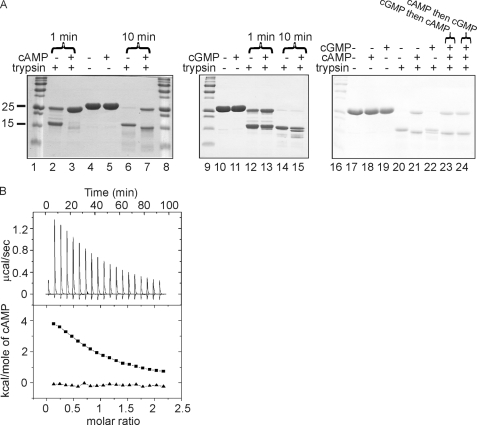

FIGURE 1.

Characterization of cAMP binding by CRPMt. A, digestion of CRPMt (15 μg) by trypsin (1 μg) in the presence and absence of cAMP or cGMP (2 mm). The composition of the reaction mixtures is indicated above each lane of typical Coomassie Blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gels. For lanes 2, 3, 12, and 13, the reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 1 min. For all other lanes, the reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Lanes 1, 8, 9, and 16 are molecular mass markers; the sizes (kDa) of the relevant markers are shown on the left (the full set is 250, 150, 100, 75, 50, 37, 25, 20, 15, and 10 kDa, from top to bottom). CRPMt migrates just above the 25-kDa marker. Lane 23 shows a reaction in which CRPMt was preincubated for 10 min with cGMP before adding cAMP and trypsin, indicated by cGMP then cAMP. Lane 24 shows a reaction in which CRPMt was preincubated for 10 min with cAMP before adding cGMP and trypsin, indicated by cAMP then cGMP. B, analysis of cAMP binding by isothermal calorimetry. The upper panel shows the raw binding heats. Integrations of these peaks with respect to time and correction to a per mol basis yield the binding isotherm shown in the lower panel (squares). Also shown in the lower panel (triangles) are the heats of ligand dilution.

Isothermal calorimetry was used to determine the stoichiometry and affinity of cAMP binding to His6-CRPMt. A typical titration is shown in Fig. 1B. The data yield good nonlinear least squares fitting to a single set of identical binding sites model and are consistent with each protomer of the CRPMt dimer binding one cAMP molecule with relatively weak (Kb of ∼1.7 × 104 m−1) affinity. Furthermore, the binding of cAMP is an endothermic reaction (ΔGb −23.7 kJ mol−1) with a positive binding enthalpy (ΔHb ∼ 30.7 kJ mol−1). Therefore, the entropy change TΔSb is ∼54.4 kJ mol−1 K−1, and hence cAMP binding is entropically driven. Chemical cross-linking showed that CRPMt is a dimer (not shown), and thus the data indicate that unlike the E. coli CRP dimer, the two cAMP-binding sites in the CRPMt dimer are independent.

The effect of cAMP binding on the ability of CRPMt to bind DNA in vivo was tested in the heterologous host E. coli because M. tuberculosis has 17 predicted adenylyl cyclase proteins, and E. coli has only one, CyaA; and thus it is possible to simply create a cAMP-free background for these experiments. The parent E. coli strain was a crp lac double mutant into which a cyaA mutation was introduced. The readout (β-galactosidase activity) from the simple CRP-repressed promoter CCgalΔ4, which contains a consensus CRP site that is recognized by CRPMt located such that occupation of this site occludes the promoter (18, 34), was used as a measure of the DNA binding activity of CRPMt as shown previously by Spreadbury et al. (18). In the CyaA+ and CyaA− strains containing the vector (ptac85), transcription from the reporter was similar (761 ± 24 and 722 ± 25 Miller units, respectively, n = 5). However, in the presence of the CRPMt expression plasmid (pGS1645), reporter transcription was ∼60% lower (323 ± 86 Miller units, n = 5) in the Cya+ strain compared with that observed in the absence of CRPMt, consistent with the observations of Spreadbury et al. (18). However, in the cyaA mutant, which is unable to synthesize cAMP, the readout from the reporter in the presence of CRPMt increased by ∼2-fold (613 ± 20 Miller units, n = 5) compared with the Cya+ strain to reach ∼80% of the activity observed in the absence of CRPMt. These data are consistent with cAMP enhancing DNA binding of CRPMt in vivo.

To investigate the effect of cAMP on CRPMt DNA binding in vitro, preliminary electrophoretic mobility shift assays were used to show that CRPMt formed at least two complexes at the whiB1 promoter in the absence and presence of cAMP but that DNA binding was enhanced in the presence of cAMP (supplemental Fig. S2A). Furthermore, in cAMP titration experiments, CRPMt binding to the whiB1 promoter was enhanced when the cAMP concentration exceeded 0.05 mm (not shown), consistent with the isothermal calorimetry experiments. Moreover, the presence of the His6 tag did not significantly affect DNA binding by CRPMt in the absence (not shown) and presence of cAMP (supplemental Fig. S2B). Thus, the His6-tagged form was used in further DNA binding studies.

In summary, the work described above shows the following: (i) that CRPMt binds two cAMP molecules per dimer (one per subunit); (ii) that the cAMP-binding sites act independently; and (iii) that cAMP binding induces conformational changes in the CRPMt dimer that enhance specific DNA binding in vitro and in vivo.

whiB1 Promoter Contains Two CRPMt-binding Sites

The whiB1 gene encodes a Wbl (WhiB-like) protein. These proteins have iron-sulfur clusters and are found only in actinomycetes (26) where they are thought to function as transcription factors and/or as protein-disulfide reductases. The whiB1 transcript was less abundant in a CRPMt mutant (16), implying that CRPMt activates whiB1 expression, which was confirmed using a whiB1-lacZ fusion (17). 5′-Rapid amplification of cDNA ends was used to confirm that the whiB1 transcript start was located at 109 or 110 bp upstream of the translational start as reported by Agarwal et al. (17) (data not shown). The electrophoretic mobility shift assays (supplemental Fig. S2A) suggested the presence of more than one CRPMt-binding site in the whiB1 promoter. Inspection of the whiB1 promoter region indicated the presence of two potential CRPMt-binding sites upstream of the transcript start (Fig. 2). The first site (CRP1) located at −58.5 relative to the transcript start matches the proposed CRPMt consensus (NGTGNNANNNNNCACA) of Rickman et al. (16) in seven of the eight defined bases (Fig. 2). The second potential site (CRP2) is a poorer match to the consensus (six of the eight defined bases are matched) and is located at −37.5 relative to the transcript start. The CRP1 site has previously been implicated in CRPMt-dependent activation of whiB1 expression (17).

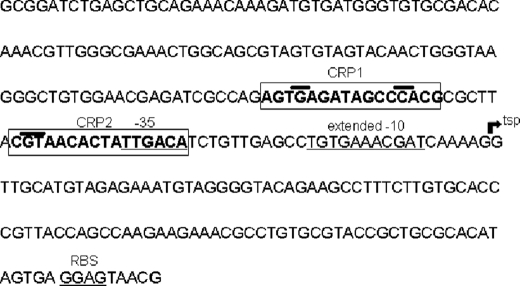

FIGURE 2.

Nucleotide sequence of the whiB1 promoter region (PwhiB1). Diagram of the nucleotide sequence of PwhiB1 showing the transcript start (tsp) and its associated extended −10 region and −35 region (underlined), two CRPMt-binding sites (boxed), and the ribosome-binding site (RBS). The locations of the nucleotides within the CRPMt-binding sites that were replaced to impair the sites as indicated in the text are overlined.

DNase I footprinting showed that both CRP1 and CRP2 sites in the whiB1 promoter were recognized by CRPMt and that binding to both sites was enhanced in the presence of cAMP (Fig. 3A). Titration of the whiB1 promoter with increasing concentrations of CRPMt showed that the CRP1 site (−70 to −51) was occupied before the CRP2 site (−50 to −29) (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, mutation of CRP1 (indicated by lowercase letters, AGTGAGATAGCCCACG to AGTtAGATAGCCaACG) or CRP2 (CGTAACACTATTGACA to CcaAACACTATTGACA) inhibited binding of CRPMt to these sites (Fig. 3B). Inactivation of CRP1 also impaired, but did not abolish, binding to CRP2 (Fig. 3B, compare lane 5 with 6). Thus, it was concluded: (i) the whiB1 promoter possesses tandem CRPMt sites, (ii) binding to these sites is enhanced in the presence of cAMP; and (iii) occupation of CRP2 is improved by occupation of CRP1.

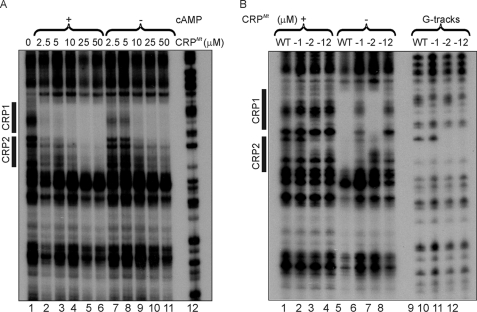

FIGURE 3.

Identification of two CRPMt-binding sites within PwhiB1. A, whiB1 promoter (PwhiB1) has two CRPMt-binding sites. Lanes 2–6 show reactions in the presence of 2 mm cAMP; lanes 7–11 show reactions in the absence of cAMP. Lane 1 shows no CRPMt; lanes 2 and 7 show 2.5 μm CRPMt; lanes 3 and 8 show 5 μm CRPMt; lanes 4 and 9 show 10 μm CRPMt; lanes 5 and 10 show 25 μm CRPMt; lanes 6 and 11 show 50 μm CRPMt; lane 12 shows Maxam and Gilbert G track. WT, wild type. B, mutation of PwhiB1 CRP1 impairs binding of CRPMt to CRP2. All reactions contained cAMP (2 mm). Lanes 1–4 show reactions of the indicated promoter variants in the absence of CRPMt as follows: −1, CRP1 site impaired (AGTGAGATAGCCCACG to AGTtAGATAGCCaACG); −2, CRP2 site impaired (CGTAACACTATTGACA to CcaAACACTATTGACA), and −12, both sites impaired. Lanes 5–8, DNase I footprints in the presence of 50 μm CRPMt. Lanes 9–12, Maxam and Gilbert G tracks. The locations of the CRP1 and CRP2 sites (see Fig. 2) are indicated by boxes. The footprints shown are typical of at least three experiments.

Both CRPMt-binding Sites in the whiB1 Promoter Are Functional

The DNase I footprinting studies indicated that there are two CRPMt sites in the whiB1 promoter. The functionality of the sites was tested by in vitro transcription experiments. Transcription from the whiB1 promoter in the presence of M. smegmatis RNAP was low (Fig. 4A, lane 3). At low concentrations of CRPMt, whiB1 transcription was enhanced, but at higher concentrations CRPMt inhibited transcription (Fig. 4A, lanes 4–8). This same pattern of regulation was observed with the untagged form of CRPMt (supplemental Fig. S3, compare lanes 3–6 and lanes 7–10), indicating that the presence of the His6 tag does not alter the transcriptional behavior of CRPMt. A similar transcription profile was observed in the presence of cAMP (Fig. 4A, lanes 9–16) except for the following: (i) there was a reproducible decrease in basal transcription (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 3 and 11), and (ii) the response curve was shifted to the left, with maximum whiB1 expression occurring in the presence of 1.3 μm CRPMt in the presence of cAMP compared with 2.5 μm CRPMt in the absence of cAMP (Fig. 4B). This result is consistent with cAMP enhancing CRPMt binding to both CRP1 and CRP2 sites in the whiB1 promoter. In conjunction with the footprinting experiments described above, these data were interpreted to mean that binding to the high affinity CRP1 site activates whiB1 transcription, whereas occupation of both CRP1 and CRP2 sites inhibits whiB1 transcription. This conclusion was supported by in vitro transcription reactions with whiB1 promoters carrying mutations in CRP1 and/or CRP2 (Fig. 4C). At a low CRPMt concentration (2.5 μm) in the absence of cAMP, the footprinting evidence indicates that CRP1 will be occupied at the wild-type promoter. Under these conditions, mutation of the CRP1 site decreased transcription of whiB1 (Fig. 4, C and D, lanes 1 and 2). Under the same conditions, mutation of CRP2 slightly enhanced whiB1 transcription (Fig. 4, C and D, lanes 1 and 3). A similar pattern was observed in the presence of cAMP (Fig. 4, C and D, lanes 5–7). At a higher CRPMt concentration (20 μm), the footprints indicate that both CRP1 and CRP2 will be occupied. Under these conditions, impairment of CRP1 had little effect on transcription compared with the wild-type promoter, i.e. transcription remained low (Fig. 4, C and D, lanes 9 and 10 and lanes 13 and 14). However, impairment of CRP2 enhanced transcription of whiB1 compared with the wild-type promoter under these conditions (Fig. 4, C and D, lanes 9 and 11, and lanes 13 and 15). Hence, these observations suggest that occupation of CRP2 is sufficient to repress basal transcription from PwhiB1. In the presence of cAMP, mutation of both CRPMt sites resulted in transcription similar to that of the unaltered promoter in the absence of CRPMt (Fig. 4, C and D, lanes 8 and 16). In the absence of cAMP, transcription from the whiB1 promoter with both CRP1 and CRP2 impaired was lower than from the unaltered promoter in the absence of CRPMt, suggesting that in the absence of cAMP there is still some unproductive interaction between CRPMt and the altered whiB1 promoter despite the impairment of both CRP-binding sites (Fig. 4, C and D, lanes 4 and 12). Note that transcription in the absence of CRPMt for all the altered promoters was the same as that for the unaltered whiB1 promoter, indicating that the changes to the sequences of the CRP sites had not affected the basal level of transcription (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

In vitro transcription from PwhiB1 is activated by CRPMt occupation of CRP1 and inhibited by CRPMt occupation of CRP2. Reactions were carried out as described under “Experimental Procedures” with the amounts of CRPMt used shown below each lane. A, typical autoradiograph showing the effects of increasing concentrations of CRPMt on whiB1 transcription in vitro. B, using the control as the standard, the relative amount of whiB1 transcript in each of the reactions shown in A was quantified and plotted as a histogram. Open bars, no cAMP; filled bars, 2 mm cAMP. C, autoradiograph showing the effects of mutation of the whiB1 CRPMt-binding sites on transcription. The whiB1 promoter variants are as described in Fig. 3B. The control and the whiB1 transcript are indicated. WT, wild type. D, using the amount of transcript formed in the absence of CRPMt as the base line, the amount of transcript formed under the indicated conditions was quantified and plotted as a histogram (black bars, wild-type promoter; gray bars, CRP1 impaired; stippled bars, CRP2 impaired; open bars, CRP1 and CRP2 impaired). The in vitro transcriptions shown are typical of at least three experiments. The amount of transcription relative to that observed in the absence of CRPMt was calculated by dividing the mean of the test condition by that measured in the absence of CRPMt and expressing this value as a fold difference.

The in vitro transcription experiments showed that CRPMt acts as both an activator (at low concentrations) and repressor (at high concentrations) of whiB1 expression. Permanganate footprinting to detect open complex formation showed the presence of quantitatively similar distortions of DNA at nucleotide T −8 in the whiB1 promoter mediated by RNAP in the presence or absence of 2.5 μm CRPMt (Fig. 5A, lanes 3, 4, 8, and 9). This evidence suggests that CRPMt-mediated activation of whiB1 expression probably occurs after open complex formation, because in the absence of CRPMt transcription from the whiB1 promoter is low (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 3 and 4). In the presence of 20 μm CRPMt, the open complex was not detected (Fig. 5A, lanes 5 and 10) indicating that higher concentrations of CRPMt inhibit whiB1 expression at a point before open complex formation, probably by inhibiting RNAP binding.

FIGURE 5.

M. tuberculosis CRP activates whiB1 transcription after open complex formation. A, permanganate footprints were obtained with PwhiB1 in the presence and absence of M. smegmatis RNAP and CRPMt. Lanes 1 and 6 show CRPMt 2.5 μm only; lanes 2 and 7 show CRPMt 20 μm only; lanes 3 and 8 show RNAP only; lanes 4 and 9 show RNAP plus CRPMt 2.5 μm; lanes 5 and 10 show RNAP plus CRPMt 20 μm; lane 11 shows Maxam and Gilbert G track. Lanes 1–5 show reactions in the absence of cAMP; lanes 6–10 show reactions in the presence of cAMP (2 mm). The location of the −10 element is indicated. B, DNase I footprint of PwhiB1 in the presence of an activating concentration of CRPMt (2.5 μm) and RNAP. Lanes 1 and 2 show no protein; lanes 3 and 4 show CRPMt; lanes 5 and 6 show CRPMt plus RNAP; lane 7 shows Maxam and Gilbert G track. The locations of the CRP1 (protected) and CRP2 (unprotected) sites are indicated by filled rectangles, as is the region of protection afforded by RNAP. The location of the −10 element is also marked. The hypersensitive site within CRP2 that appears in the presence of RNAP is indicated by the arrow. The footprints shown are typical of at least three experiments.

DNase I footprinting of the whiB1 promoter in the presence of M. smegmatis RNAP and activating concentrations of CRPMt (2.5 μm) showed that RNAP could bind at the promoter when the CRP1 site was occupied and that this was accompanied by the appearance of an RNAP-dependent hypersensitive site at position −34, which is within the CRP2 site (Fig. 5B). The presence of the hypersensitive site is attributed to docking of the C-terminal domain of the RNAP α-subunit downstream of CRPMt bound at CRP1.

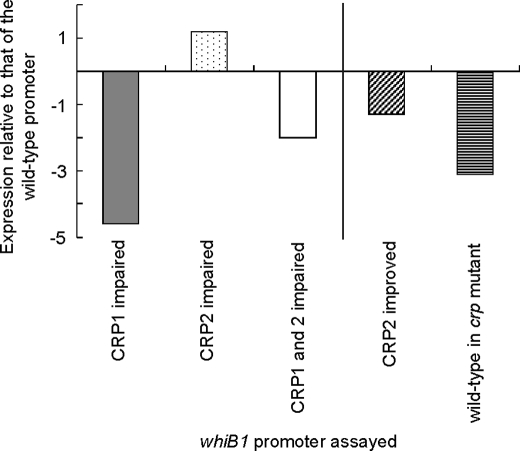

To determine whether the effects of CRPMt on whiB1 transcription observed in vitro were also apparent in vivo, a promoter fusion containing DNA from −187 to 129 relative to the transcript start was fused upstream of a lac reporter gene, and transcription was estimated in M. tuberculosis wild-type H37Rv and an isogenic Rv3676 (crp) mutant (Fig. 6). Under exponential growth conditions, expression of whiB1 was decreased by ∼3-fold in the CRPMt mutant (ΔRv3676), consistent with CRPMt-dependent activation. An ∼5-fold reduction in expression was observed when the CRP1 site was disabled, reflecting the absence of activation from CRP1 but retention of repression from CRP2. Accordingly, mutation of CRP2, without disrupting the −35 element (underlined) of the whiB1 promoter (CGTAACACTATTGACA to CcaAACACTATTGACA), resulted in a small but reproducible increase in whiB1 expression. Similarly, improvement of the CRP2 site (CGTAACACTATTGACA to CGTgACACTATTGACA) caused a reproducible decrease in whiB1 expression. Disabling both CRP1 and CRP2 lowered β-galactosidase activities by an amount similar to that observed using the unaltered promoter in the crp mutant. The in vivo data correlated well with the in vitro transcription data as shown in Fig. 4, C and D. Thus, when 2.5 μm CRPMt was used in the in vitro transcription reactions (Fig. 4D), the fold changes in transcription upon impairment of CRP-binding sites compared with the unaltered promoter were as follows: −3.5 to −2.4 when CRP1 was impaired; +1.2 to +1.6 when CRP2 was impaired; and −2.6 to −2.0 when both CRP1 and CRP2 were impaired. These values are similar to those obtained for transcription in vivo (Fig. 6) as follows: −4.6 when CRP1 was impaired; +1.2 when CRP2 was impaired; and −2.0 when CRP1 and CRP2 were impaired. Hence, the in vitro and in vivo experiments are consistent with a mechanism in which occupation of CRP1 enhances whiB1 expression, whereas occupation of both CRP1 and CRP2 or of CRP2 alone represses whiB1 expression in M. tuberculosis.

FIGURE 6.

Patterns of whiB1 expression in vivo match those seen in vitro. β-Galactosidase assays were performed on cell extracts from M. tuberculosis H37Rv strains containing constructs with PwhiB1 promoter linked to the lacZ reporter gene. These were as follows: the unaltered PwhiB1 (wild-type), PwhiB1 with the CRP1 site impaired (CRP1 impaired), PwhiB1 with the CRP2 site impaired (CRP2 impaired), and PwhiB1 with both the CRP1 and CRP2 sites impaired (CRP1 and 2 impaired). The effects of the mutations made in the CRP sites are shown as expression relative to that of the unaltered wild-type promoter to allow direct comparison with the in vitro transcription assays in Fig. 4D. Thus, the result for PwhiB1 with an impaired CRP1 site is shown as a gray bar; the result for PwhiB1 with an impaired CRP2 site is shown as a stippled bar, and the result for PwhiB1 with impaired CRP1 and CRP2 sites is shown as an open bar. In addition, on the right of the figure, the effect of improving the CRP2 site of PwhiB1 (CRP2 improved; diagonal stripes) as well as expression from unaltered PwhiB1 in H37Rv ΔRv3676 (wild-type in crp mutant strain; horizontal stripes) is shown. The values shown are calculated from the mean β-galactosidase activities from three bacterial cultures. All assays were done in triplicate and varied by <15%. The expression relative to the unaltered whiB1 promoter in M. tuberculosis H37Rv was calculated by dividing the mean of the test condition by that obtained for the wild-type promoter and expressing this value as a fold change.

DISCUSSION

The work described here shows that CRPMt is a homodimeric protein with one cAMP-binding site per protomer. This conclusion is substantiated by the crystal structure of CRPMt bound to cAMP that was published during the review of this manuscript (43). For E. coli CRP, cAMP binding is cooperative; the first binding event is exothermic and the second is endothermic, and the sensory domain binding sites are saturated by micromolar concentrations of cAMP (44). This is not the case for CRPMt where the cAMP-binding sites are independent. The cAMP binding parameters for CRPMt are similar to those for cGMP binding to E. coli CRP, except that the thermodynamic properties of these interactions are opposite; CRPMt cAMP binding has a positive enthalpy, whereas E. coli CRP cGMP binding is exothermic (44). Recently, cAMP binding by E. coli CRP has been shown to reorganize the major helices that form the dimer interface, thereby rotating the DNA binding domains so that they can interact with adjacent major grooves in target DNA (45). The differences in binding of cAMP by the E. coli and M. tuberculosis CRP proteins suggest that the signal transduction pathways that promote site-specific DNA binding might be different, and this might be reflected in the relatively small enhancement in DNA binding caused by addition of cAMP.

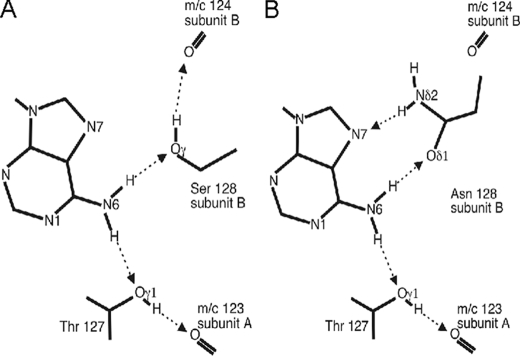

Comparison of the cAMP binding pockets of CRPMt (44) and E. coli CRP (46, 47) reveals that most of the side chains that contact cAMP are either conserved or are conservatively substituted. The significant difference between the two proteins, in the context of the independent cAMP binding of CRPMt compared with the cooperative cAMP binding of E. coli CRP, is the substitution of Ser-128 in E. coli CRP by Asn in CRPMt. Ser-128 makes a cross-subunit contact with cAMP in E. coli CRP; i.e. Ser-128 of subunit B interacts with cAMP bound at subunit A (46, 47). Fig. 7 shows that the N6 position of cAMP is able to donate two hydrogen bonds, which interact with the acceptor γ oxygen atoms of Thr-127 of one subunit (subunit A) and of Ser-128 in the other subunit (subunit B) in E. coli CRP. The latter two atoms are constrained to act as acceptors because they in turn donate hydrogen bonds to the main chain carbonyl acceptors of residues 123 in subunit A and 124 in subunit B, respectively. Residues 123 and 124 are located in the dimerization helices of the two E. coli CRP subunits. The N6 of the adenosine moiety of cAMP therefore acts via Thr-127 of subunit A and Ser-128 of subunit B as a bridge between the main chains of the dimerization helices of the two subunits (Fig. 7A). A reciprocal interaction occurs when cAMP is bound in the other site of the CRP dimer, and hence the cAMP-binding sites of each protomer are connected. In CRPMt, the equivalent position to Ser-128 is occupied by Asn-135, and this does not significantly alter the position of cAMP. However, the Asn side chain makes two hydrogen bonds to cAMP; the ND2 of the Asn side chain can donate an H bond to the N7 of cAMP, and the OD1 atom can accept a hydrogen bond from one of the N6 donor hydrogen atoms (Fig. 7B). This pattern of interactions removes the possibility of the side chain of Asn-135 donating a hydrogen bond to the main chain carbonyl of residue 131 of subunit B. For this reason, replacement of the Ser by Asn at this position uncouples the cAMP-binding sites in CRPMt. Consistent with this interpretation, the substitution of Ser-128 by Ala in E. coli CRP abolishes cooperative cAMP binding (48).

FIGURE 7.

Schematic diagram of hydrogen bonding contacts of the adenine groups of cAMP in the binding pockets of E. coli and M. tuberculosis CRP proteins. A, observed hydrogen bonds between cAMP and E. coli CRP (Protein Data Bank code 2cgp) (45). B, predicted hydrogen bonds between cAMP and CRPMt in which Ser-128 is replaced by Asn. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dotted arrows from donor to acceptor. Atoms referred to in the text are labeled.

Although cAMP enhanced binding of recombinant CRPMt to target DNA, this enhancement was not comparable with that observed with E. coli CRP, where DNA-binding affinity is enhanced by several orders of magnitude in the presence of 0.1 mm cAMP, allowing specific DNA binding at nanomolar concentrations (27, 48). For CRPMt, a much less significant enhancement of DNA binding was observed, and higher concentrations of cAMP compared with E. coli CRP were required. This may point to meaningful physiological changes in cAMP concentration in M. tuberculosis occurring at higher levels than those in E. coli. Indeed, cAMP concentrations in mycobacteria have been reported to be rather high (49), being ∼100–200-fold greater than for E. coli. The high intracellular concentration of cAMP in M. tuberculosis is consistent with the numerous adenylyl cyclases synthesizing cAMP. This and the reported increase in cAMP levels that occurs after infection of macrophages by pathogenic mycobacteria (5–7) point to cAMP being an important signaling molecule in infection. The evidence presented here suggests that, perhaps as a consequence of the high intracellular concentrations of cAMP in M. tuberculosis, CRPMt has evolved a different mode of interaction with cAMP compared with the E. coli paradigm, involving low affinity binding of cAMP to independent sites. Nevertheless, the response of CRPMt to cAMP was very significant for expression of whiB1.

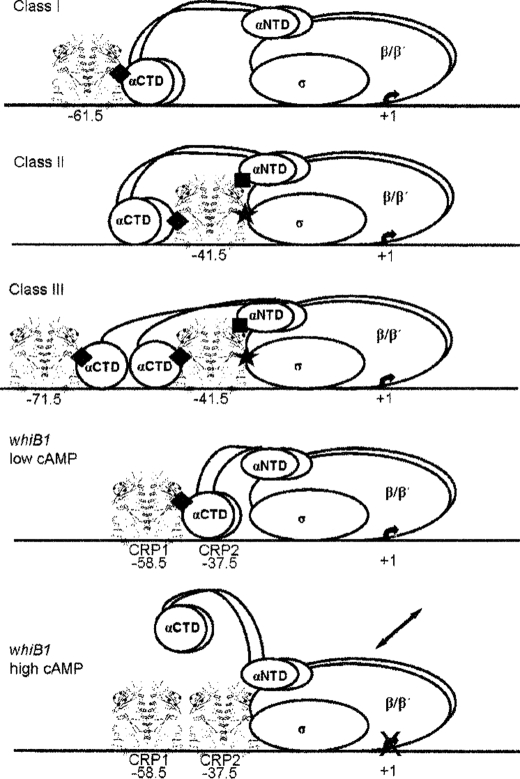

Several different classes of regulated bacterial promoters have been identified based on the locations of the binding sites for transcription activators. Promoters dependent on transcription factors bound at or close to −61 are known as class I promoters (Fig. 8). At these promoters a specific region, known as activating region 1 (AR1), of the transcription factor interacts with the C-terminal domain of the α-subunit (α-CTD) of RNAP to activate transcription. A common alternative architecture is that of the class II promoters, in which the transcription factor binds to a site that overlaps the core −35 element of the promoter. At class II promoters multiple interactions between the transcription factor and RNAP are possible, including an AR1 interaction with α-CTD, an AR2 interaction with the RNAP α-subunit N-terminal domain, and interaction between AR3 and the σ-subunit of RNAP (Fig. 8). Class III promoters have transcription factors bound in tandem making both class I- and class II-type interactions with RNAP (Fig. 8). The experiments described here and elsewhere show that expression of whiB1 is dependent on CRPMt and that this requires a CRPMt-binding site centered 58.5 bp upstream of the transcript start, a class I location (16, 17). However, it is now shown that there is a second, lower affinity, negatively acting CRP-binding site (CRP2 centered at −37.5) located immediately downstream of CRP1 that has significant implications for cAMP-CRPMt-mediated regulation of whiB1 expression. The identification of a second class II CRPMt-binding site (CRP2) that is occupied when cAMP levels increase and inhibits whiB1 activation by CRPMt bound at the class I site (CRP1) indicates that whiB1 expression in vivo should be maximal at intermediate cAMP concentrations. Hence, the following model for cAMP-responsive whiB1 expression provides the simplest explanation for the data described here. The locations of the two CRPMt-binding sites (−58.5 and −37.5) are such (centers of the sites are separated by 21 bp) that they are located on the same face of the DNA helix. At low concentrations of the CRPMt-cAMP complex, CRP1 is preferentially occupied (Fig. 3A); the α-CTD of RNAP docks downstream of CRP1 (Fig. 5B), and transcription of whiB1 is activated via a class I mechanism (Fig. 8). Activation of class I promoters by E. coli CRP occurs solely by recruiting RNAP to the promoter by increasing the binding constant for the formation of the RNAP-promoter closed complex (reviewed in Ref. 10). However, the permanganate footprints suggest that low (nonrepressing; Fig. 4A) concentrations of CRPMt or CRPMt-cAMP do not significantly enhance open complex formation at the whiB1 promoter compared with reactions lacking CRPMt (Fig. 5A) indicating that a step after open complex formation is activated. Further experimental work will be needed to identify the mechanism by which this is achieved.

FIGURE 8.

Architecture of CRP-dependent promoters. The diagram shows the arrangement of nucleoprotein complexes formed at typical class I, class II, and class III CRP-dependent promoters. At class I promoters, the center of the CRP dimer (shown in ribbon form) is positioned at −61.5, −71.5, −81.5, or −91.5 upstream of the transcript start, placing it on the same face of the DNA helix (horizontal line) as RNAP (shown as unfilled ellipses). This arrangement allows the C-terminal domain of the RNAP α-subunit (α-CTD) to interact directly with activating region 1 (AR1) of the downstream subunit of the CRP dimer (♦). At class II promoters, the CRP dimer is centered at or close to −41.5 and is again on the same face of the DNA helix as RNAP. At these promoters multiple interactions between CRP and RNAP are possible, with contacts between AR1 of the upstream subunit of the CRP dimer and α-CTD, and between activating region 2 (AR2) of the downstream subunit of the CRP dimer and the N-terminal domain of the RNAP α-subunit (α-NTD; ■), and activating region 3 (AR3) of the same CRP subunit and the RNAP σ factor (★). Class III promoters have tandem CRP sites in class I and class II locations allowing AR1, AR2, and AR3 contacts with RNAP. For E. coli CRP, these protein-protein interactions recruit RNAP to CRP-dependent promoters (10). For M. tuberculosis PwhiB1 at low cAMP-CRPMt concentrations, CRP1 is occupied and expression is activated, not by RNAP recruitment but by enhancing a step after open complex formation, i.e. promoter clearance. At high cAMP-CRPMt concentrations, CRP1 and CRP2 are occupied. This arrangement has some similarities with the class III architecture, but because the CRP1 and CRP2 sites are immediately adjacent, there is insufficient space to accommodate the α-CTD between the tandem CRP dimers resulting in inhibition of transcription by preventing α-CTD from docking with DNA thereby inhibiting productive interaction of RNAP with PwhiB1 (indicated by the double-headed arrow).

At higher CRPMt or CRPMt-cAMP concentrations, both CRP1 (class I position) and CRP2 (class II position) are occupied (Fig. 3A). Occupation of both CRP1 and CRP2 sites would leave little space between the two CRPMt dimers, preventing the formation of a typical class III nucleoprotein complex and thus the RNAP α-CTD is displaced, which is likely to result in either poor or unproductive binding of RNAP to the whiB1 promoter (Fig. 8). In this way, occupation of CRP2 by CRPMt antagonizes activation by CRPMt bound at CRP1 resulting in inhibition of whiB1 transcription. Because the concentration of cAMP in M. tuberculosis increases during infection of macrophages (5, 7), this suggests that whiB1 might be expressed transiently during infection. Although the available microarray datasets (50, 51) do not suggest that whiB1 expression responds transiently at the time points sampled, this study indicates that the possibility that whiB1 is transiently expressed during infection should be tested by obtaining high resolution long time course gene expression data to determine the significance of any such transient expression for M. tuberculosis pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor S. J. W. Busby (University of Birmingham) for the gift of the CCgalΔ4 plasmid and Luc Gaudreau and Jocelyn Beaucher (Université de Sherbrooke, Canada) for advice on RNAP purification and for a control template for in vitro transcription assays.

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust Grant 078731/Z/05/Z and the Medical Research Council.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- CRP

- cyclic AMP receptor protein

- α-CTD

- RNA polymerase α-subunit C-terminal domain

- CRPMt

- M. tuberculosis CRP protein encoded by the gene Rv3676

- RNAP

- RNA polymerase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dye C., Scheele S., Dolin P., Pathania V., Raviglione M. C. (1999) J. Am. Med. Assoc. 282, 677–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russell D. G. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 569–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stewart G. R., Robertson B. D., Young D. B. (2003) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1, 97–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole S. T., Brosch R., Parkhill J., Garnier T., Churcher C., Harris D., Gordon S. V., Eiglmeier K., Gas S., Barry C. E., 3rd, Tekaia F., Badcock K., Basham D., Brown D., Chillingworth T., Connor R., Davies R., Devlin K., Feltwell T., Gentles S., Hamlin N., Holroyd S., Hornsby T., Jagels K., Krogh A., McLean J., Moule S., Murphy L., Oliver K., Osborne J., Quail M. A., Rajandream M. A., Rogers J., Rutter S., Seeger K., Skelton J., Squares R., Squares S., Sulston J. E., Taylor K., Whitehead S., Barrell B. G. (1998) Nature 393, 537–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agarwal N., Lamichhane G., Gupta R., Nolan S., Bishai W. R. (2009) Nature 460, 98–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lowrie D. B., Jackett P. S., Ratcliffe N. A. (1975) Nature 254, 600–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bai G., Schaak D. D., McDonough K. A. (2009) FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 55, 68–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gazdik M. A., McDonough K. A. (2005) J. Bacteriol. 187, 2681–2692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busby S., Kolb A. (1996) in Regulation of Gene Expression in Escherichia coli (Lin E. C., Lynch A. S. eds) pp. 255–279, R. G. Landes Co., Austin, TX [Google Scholar]

- 10.Busby S., Ebright R. E. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 293, 199–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grainger D. C., Hurd D., Harrison M., Holdstock J., Busby S. J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 17693–17698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirin E., Sismeiro O., Danchin A., Bertin P. N. (2002) Microbiology 148, 1553–1559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berg O. G., von Hippel P. H. (1988) J. Mol. Biol. 200, 709–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Browning D. F., Busby S. J. (2004) Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bai G., McCue L. A., McDonough K. A. (2005) J. Bacteriol. 187, 7795–7804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rickman L., Scott C., Hunt D. M., Hutchinson T., Menéndez M. C., Whalan R., Hinds J., Colston M. J., Green J., Buxton R. S. (2005) Mol. Microbiol. 56, 1274–1286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agarwal N., Raghunand T. R., Bishai W. R. (2006) Microbiology 152, 2749–2756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spreadbury C. L., Pallen M. J., Overton T., Behr M. A., Mostowy S., Spiro S., Busby S. J., Cole J. A. (2005) Microbiology 151, 547–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bai G., Gazdik M. A., Schaak D. D., McDonough K. A. (2007) Infect. Immun. 75, 5509–5517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunt D. M., Saldanha J. W., Brennan J. F., Benjamin P., Strom M., Cole J. A., Spreadbury C. L., Buxton R. S. (2008) Infect. Immun. 76, 2227–2234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mukamolova G. V., Turapov O. A., Young D. I., Kaprelyants A. S., Kell D. S., Young M. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 46, 623–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.den Hengst C. D., Buttner M. J. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1780, 1201–1216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jakimowicz P., Cheesman M. R., Bishai W. R., Chater K. F., Thomson A. J., Buttner M. J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 8309–8315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alam M. S., Garg S. K., Agrawal P. (2009) FEBS J. 276, 76–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh A., Crossman D. K., Mai D., Guidry L., Voskuil M. I., Renfrow M. B., Steyn A. J. (2009) PLoS Pathogens 8, e1000545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soliveri J. A., Gomez J., Bishai W. R., Chater K. F. (2000) Microbiology 146, 333–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Takahashi M., Blazy B., Baudras A. (1989) J. Mol. Biol. 207, 783–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casadaban M. J., Cohen S. N. (1980) J. Mol. Biol. 138, 179–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Busby S., Kotlarz D., Buc H. (1983) J. Mol. Biol. 167, 259–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kubica G. P., Kim T. H., Dunbar F. P. (1972) Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 22, 99–106 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snapper S. B., Melton R. E., Mustafa S., Kieser T., Jacobs W. R., Jr. (1990) Mol. Microbiol. 4, 1911–1919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lodge J., Williams R., Bell A., Chan B., Busby S. (1990) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 67, 221–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marsh P. (1986) Nucleic Acids Res. 14, 3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bell A., Gaston K., Williams R., Chapman K., Kolb A., Buc H., Minchin S., Williams J., Busby S. (1990) Nucleic Acids Res. 18, 7243–7250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papavinasasundaram K. G., Anderson C., Brooks P. C., Thomas N. A., Movahedzadeh F., Jenner P. J., Colston M. J., Davis E. O. (2001) Microbiology 147, 3271–3279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sambrook J. W., Russell D. W. (2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd Ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiseman T., Williston S., Brandts J. F., Lin L. N. (1989) Anal. Biochem. 179, 131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller J. H. (1972) Experiments in Molecular Genetics, pp. 352–355, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maxam A. M., Gilbert W. (1980) Methods Enzymol. 65, 499–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Beaucher J., Rodrigue S., Jaques P. E., Smith I., Brzezinski R., Gaudreau L. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 45, 1527–1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akter Y., Tundup S., Hasnain S. E. (2007) Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297, 451–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Angulo J., Krakow J. S. (1986) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 11315–11319 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reddy M. C., Palaninathan S. K., Bruning J. B., Thurman C., Smith D., Sacchettini J. C. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 36581–36591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gorshkova I., Moore J. L., McKenney K. H., Schwarz F. P. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 21679–21683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Popovych N., Tseng S. R., Tonelli M., Ebright R. H., Kalodimos C. G. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 6927–6932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weber I. T., Steitz T. A. (1987) J. Mol. Biol. 198, 311–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Passner J. M., Steitz T. A. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 2843–2847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Moore J. L., Gorshkova I. I., Brown J. W., McKenney K. H., Schwarz F. P. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21273–21278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Padh H., Venkitasubramanian T. A. (1976) Microbios 16, 183–189 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rohde K. H., Abramovich R. B., Russell D. G. (2007) Cell Host Microbe 2, 352–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schnappinger D., Ehrt S., Voskuil M. I., Liu Y., Mangan J. A., Monahan I. M., Dolganov G., Efron B., Butcher P. D., Nathan C., Schoolnik G. K. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 198, 693–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.