Abstract

The G protein-coupled receptor P2Y2 nucleotide receptor (P2Y2R) has been shown to be up-regulated in a variety of tissues in response to stress or injury. Recent studies have suggested that P2Y2Rs may play a role in immune responses, wound healing, and tissue regeneration via their ability to activate multiple signaling pathways, including activation of growth factor receptors. Here, we demonstrate that in human salivary gland (HSG) cells, activation of the P2Y2R by its agonist induces phosphorylation of ERK1/2 via two distinct mechanisms, a rapid, protein kinase C-dependent pathway and a slower and prolonged, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-dependent pathway. The EGFR-dependent stimulation of UTP-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in HSG cells is inhibited by the adamalysin inhibitor tumor necrosis factor-α protease inhibitor or by small interfering RNA that selectively silences ADAM10 and ADAM17 expression, suggesting that ADAM metalloproteases are required for P2Y2R-mediated activation of the EGFR. G protein-coupled receptors have been shown to promote proteolytic release of EGFR ligands; however, neutralizing antibodies to known ligands of the EGFR did not inhibit UTP-induced EGFR phosphorylation. Immunoprecipitation experiments indicated that UTP causes association of the EGFR with another member of the EGF receptor family, ErbB3. Furthermore, stimulation of HSG cells with UTP induced phosphorylation of ErbB3, and silencing of ErbB3 expression inhibited UTP-induced phosphorylation of both ErbB3 and EGFR. UTP-induced phosphorylation of ErbB3 and EGFR was also inhibited by silencing the expression of the ErbB3 ligand neuregulin 1 (NRG1). These results suggest that P2Y2R activation in salivary gland cells promotes the formation of EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimers and metalloprotease-dependent neuregulin 1 release, resulting in the activation of both EGFR and ErbB3.

Keywords: G Proteins/Coupled Receptors (GPCR), Tissue/Organ Systems/Epithelium, Tissue/Organ Systems/Salivary Gland, Growth Factors, Metalloprotease, EGFR, ErbB3, P2Y2 Receptor

Introduction

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs),3 the largest group of cell surface receptors, function not only as short term modulators of cell metabolism but also as regulators of cellular growth and differentiation via activation of the ERK/MAPK signaling cascade (1–5). The mechanisms whereby GPCRs activate the ERK/MAPK signaling pathway are complex and vary according to the type of GPCR and the tissue in which the receptor is expressed (1, 6, 7). During the past decade, numerous studies have demonstrated that GPCRs can couple to the ERK/MAPK signaling cascade directly through a G protein-dependent pathway or indirectly by activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR, also known as ErbB1) (1, 8–10). Mediators of GPCR-induced ERK/MAPK activation include Src tyrosine kinase (6, 11–15), protein kinase C (PKC) (6, 11, 12), proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (13, 14), increases in the intracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) (15, 16), reactive oxygen species (17–19), and metalloprotease-dependent shedding of an EGFR ligand (8, 20–22). EGFR ligands promote homodimerization and autophosphorylation of the EGFR (23), resulting in activation of the ERK/MAPK signaling cascade (24). However, EGFR phosphorylation also can be achieved by heterodimerization with another member of the ErbB receptor family, including ErbB2, ErbB3, or ErbB4 (25). The preferred partner for EGFR heterodimerization (similar for ErbB3 and ErbB4) is ErbB2, a ligandless receptor that is considered to be a nonautonomous amplifier of the ErbB network (26) particularly in cancer biology (27, 28). EGFR also can dimerize with either ErbB3 or ErbB4 upon ligand binding (25). Moreover, because ErbB3 has an inactive kinase domain, it must dimerize with another ErbB family member to respond to its only known ligand, neuregulin (NRG) (25). The activation of ErbB homo- and heterodimers by their ligands stimulates multiple signal transduction pathways that regulate physiological responses, such as cell proliferation, migration, differentiation, and wound healing (24, 29) or an aberrant response in cancer (28). Thus, the mechanisms whereby GPCRs can activate ErbB family members have significant physiological and pathophysiological relevance.

The P2Y2 nucleotide receptor (P2Y2R) is a Gq11-coupled protein that is activated equipotently by extracellular ATP or UTP, leading to Gαq-dependent activation of phospholipase C, which generates two second messengers: inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate that increases [Ca2+]i via calcium release from intracellular stores and diacylglycerol that activates PKC (30, 31). The P2Y2R is up-regulated in a variety of tissues in response to injury or stress, including salivary gland epithelium (32–34). The physiological consequences of P2Y2R expression in the salivary gland are unknown; however, our recent studies with human salivary gland (HSG) cells suggest that P2Y2R activation may contribute to the immune response associated with Sjögren's syndrome, an autoimmune exocrinopathy of the salivary gland (35). P2Y2Rs also have been suggested to play a role in epithelial wound healing (36–38), intimal hyperplasia in blood vessels (39, 40), liver regeneration (41), inflammatory bowel disease (42), and phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells (43).

The P2Y2R contains two Src homology 3 domain-binding sites (PXXP motifs) in its intracellular C-terminal domain that mediate the binding of Src and the Src-dependent activation of growth factor receptors (40, 44). In addition to the Src homology 3 domain-binding motifs, the P2Y2R also contains an Arg-Gly-Asp sequence in its first extracellular loop that has been shown to interact with αvβ3/β5 integrins (45) that regulate ATP- and UTP-induced cell chemokinesis and chemotaxis (46) and promote the activation of MAPKs and stress-activated protein kinases (44). Recently, we found that the human P2Y2R expressed in a P2Y receptor-null cell line (human 1321N1 astrocytoma cells) mediates the proprotein convertase furin-dependent activation of ADAM10 and ADAM17 (47) that mediate the release/shedding of EGFR ligands, including EGF, heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor, TGFα, amphiregulin, epiregulin, and betacellulin (48) as well as the ErbB3/ErbB4 ligand, NRG1 (49, 50). The EGF family of receptors and their ligands are crucial for salivary gland growth and acinar differentiation (51–54); therefore, mechanisms whereby P2Y2Rs can activate the EGFR may be useful to promote repair and/or regeneration of damaged or diseased salivary gland tissue, as occurs in Sjögren's syndrome or when salivary glands are damaged by irradiation to treat head and neck cancers. The present study indicates that P2Y2Rs in HSG cells activate ERK1/2 by two distinct pathways, a rapid PKC-dependent mechanism and a slower metalloprotease- and EGFR-dependent mechanism. P2Y2R-mediated EGFR activation in HSG cells is dependent on the expression of ErbB3 and the ErbB3 ligand NRG1 and likely requires the formation of EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimers and the stimulation of the metalloproteases ADAM10/17 to catalyze the release of NRG1.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

All of the chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise stated. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum were obtained from Invitrogen. AG1478 and GF109303 were purchased from Calbiochem. Tumor necrosis factor-α protease inhibitor (TAPI-2) was purchased from Peptides International (Louisville, KY). Recombinant human HBEGF, TGFα, amphiregulin, epigen, betacellulin, neuregulin-1 (heregulin 1 or NRG1), and neutralizing antibodies were purchased from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Cell Culture

HSG cells were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air.

Preparation of Dispersed Cell Aggregates from Mouse SMG

Dispersed cell aggregates from SMGs of wild type (wt) C57BL/6 and C57BL/6 P2Y2R−/− mice were prepared, as described previously for rats (32). Protocols conformed to Animal Care and Use Guidelines of the University of Missouri. Briefly, the mice were anesthetized with isofluorane and SMGs removed. The glands were finely minced and incubated in dispersion medium consisting of DMEM/Ham's F-12 medium (1:1) (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 0.2 mm CaCl2, 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin, 50 units/ml collagenase (Worthington Biochemical, Freehold, NJ), and 400 units/ml hyaluronidase at 37 °C for 40 min with aeration (95% air and 5% CO2). Cell aggregates in dispersion medium were suspended by pipetting at 20, 30 and 40 min of the incubation period. The dispersed cell aggregates were washed with enzyme-free assay buffer (120 mm NaCl, 4 mm KCl, 1.2 mm KH2PO4, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 1 mm CaCl2, 10 mm glucose, 15 mm HEPES, pH 7.4) containing 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin, filtered through nylon mesh, and cultured in DMEM/F-12 medium (1:1) containing 2.5% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and the following supplements: 0.1 μm retinoic acid, 80 ng/ml epidermal growth factor, 2 nm triiodothyronine, 5 mm glutamine, 0.4 μg/ml hydrocortisone, 5 μg/ml insulin, 5 μg/ml transferrin, 5 ng/ml sodium selenite, 50 μg/ml gentamicin, and 8.4 ng/ml cholera toxin. The cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 for 72 h.

Western Blot Analysis

HSG cells were seeded on 12-well culture dishes and grown until ∼80–90% confluence. Then the cells were incubated overnight in DMEM without serum. When indicated, the cells were pretreated with or without inhibitors (30 min) or neutralizing antibodies (60 min) before stimulation with agonists for the indicated times. Then the medium was removed, and 200 μl of 2× Laemmli lysis buffer (20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 20% (v/v) glycerol, 4% (w/v) SDS, 0.01% (w/v) bromphenol blue, and 100 mm dithiothreitol) were added; the samples were sonicated for 5 s with a Branson Sonifier 250 (microtip; output level, 5; duty cycle, 50%), heated at 95 °C for 4 min, and subjected to SDS-PAGE on 7.5% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels. The proteins resolved on the gel were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and blocked for 1 h with 5% (w/v) nonfat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST). The blots were incubated overnight at 4 °C in TBST with the following rabbit polyclonal antibodies used at 1:1000 dilutions: anti-phospho-EGFR (Tyr1068), anti-phospho-ErbB3 (Tyr1289), or anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). To detect total protein expression, the following rabbit polyclonal antibodies were used at 1:2000 dilutions: anti-EGFR, anti-ErbB3, or anti-ERK1/2. The membranes were washed three times with TBST and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:2000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were washed three times with TBST and incubated with enhanced chemiluminescence reagent, and the protein bands detected on x-ray film were quantified using a computer-driven scanner and Quantity One software (Bio-Rad). The intensities of phosphorylated protein bands in cells treated with agonist or other agents were normalized to total ERK1/2, EGFR, or ErbB3 and expressed as a percentage of normalized data from untreated controls.

Immunoprecipitation of EGFR

HSG cells were serum-starved for 18 h and stimulated with agonists as indicated. The medium was removed, and the cells were incubated in 0.5 ml of lysis buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 200 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1.25% (v/v) Nonidet P-40, 0.2% (w/v) SDS, and Complete protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science)) for 10 min at 4 °C. Then cell lysates were incubated overnight with 5 μg of rabbit anti-EGFR antibody at 4 °C. The immunoprecipitates were collected by incubation with 50 μl of protein G-agarose suspension (Roche Applied Science) for 2 h at 4 °C. The immune complexes were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C and washed three times in lysis buffer. The final pellet was resuspended in 60 μl of 2× Laemmli buffer, heated at 95 °C for 4 min, and centrifuged for 5 s at 12,000 × g to pellet beads, and the supernatant was subjected to SDS-PAGE on 7.5% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels, as described above.

siRNA-mediated Suppression of Src, ADAM10, ADAM17, ErbB3, and NRG1 Expression

HSG cells were transfected in reduced-serum medium (Opti-MEM) with 100 nm SMARTpool of double stranded small interfering RNA specific for the mRNAs of Src, ADAM10, ADAM17, ErbB3, or NRG1 (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO), according to the manufacturer's instructions at 1:2.5 (v/v) siRNA:Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Nonspecific siRNA (100 nm) (Dharmacon) was used as a negative control. After 6 h, the medium was replaced with growth medium (see “Cell Culture”) for 24 h and then the cells were serum-starved for 18 h prior to experimentation. Transfection efficiency of targeted siRNA for suppression of protein expression was confirmed by Western analysis with the following rabbit polyclonal antibodies at 1:2000 dilutions: anti-Src (Dharmacon), anti-ADAM10, anti-ADAM17, anti-ErbB3, and anti-NRG1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), as described above.

Statistical Analysis

The quantitative results are presented as the means ± S.E. of three or more determinations, where p < 0.05 calculated from two-tailed t tests represents a significant difference.

RESULTS

P2Y2Rs Mediate the Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 via Two Distinct Mechanisms in HSG Cells

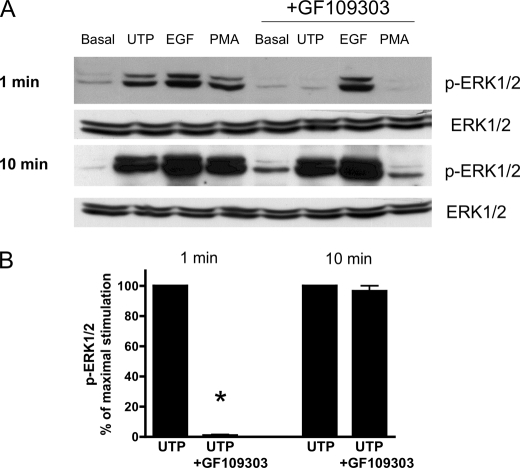

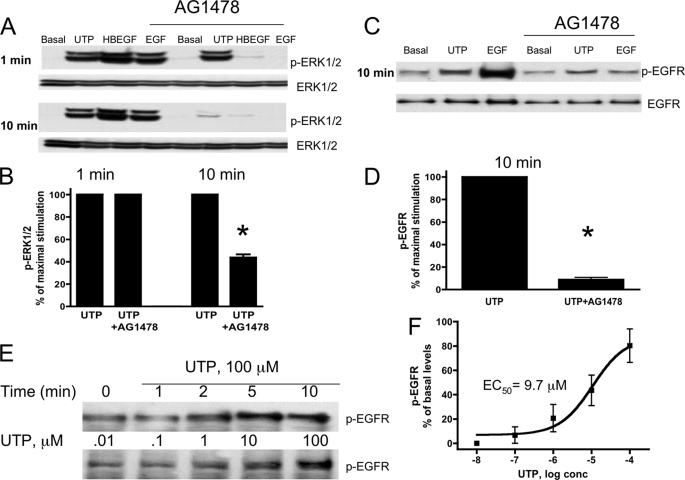

We have shown previously that HSG cells express endogenous P2Y2Rs whose activation by UTP is coupled to functional responses not regulated by other known uridine nucleotide receptors (P2Y4 or P2Y6) (35). In the present study, it is demonstrated with HSG cells that UTP induces a time- and dose-dependent increase in the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Fig. 1) with an EC50 value of ∼1 μm, a value characteristic for the P2Y2R (55). Because PKC has been implicated in P2Y2R-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation (56) and PKC is known to be activated by the P2Y2R via Gq-dependent stimulation of phospholipase C (31), we evaluated whether PKC mediates ERK1/2 phosphorylation by pretreating HSG cells for 30 min with the PKC inhibitor GF109303 (10 μm) followed by stimulation with UTP (100 μm). The results indicate that rapid (1 min) ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by UTP is attenuated by GF109303 but not the slower and prolonged (10 min) ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 2). Previously, we demonstrated that the P2Y2R mediates vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 expression in HSG cells via EGFR activation (35). Therefore, it was determined whether P2Y2R-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation is mediated by EGFR activation by pretreating HSG cells with the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 (10 μm) prior to stimulation with UTP (100 μm). The results show that AG1478 had no effect on rapid ERK1/2 phosphorylation (1 min) induced by UTP; however, AG1478 prevented the slower and prolonged ERK1/2 phosphorylation (10 min) induced by UTP (100 μm; Fig. 3, A and B), indicating that ERK1/2 phosphorylation in HSG cells occurs by both EGFR-independent and dependent pathways. In contrast to UTP, both EGF- and HBEGF-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation was inhibited by AG1478 at both the 1- and 10-min time points (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, AG1478 completely inhibited the increase in EGFR phosphorylation in HSG cells treated with EGF or UTP for 10 min (Fig. 3, C and D). However, there is no increase in EGFR phosphorylation in HSG cells treated with UTP for 1 min (Fig. 3E). At 10 min, UTP induced the dose-dependent phosphorylation of EGFR with an EC50 value of 9.7 μm (Fig. 3, E and F). These data indicate that the rapid (1 min) P2Y2R-mediated ERK1/2 phosphorylation is dependent on the activation of PKC, but not EGFR activation, whereas the slower, prolonged phase (10 min) of ERK1/2 phosphorylation is PKC-independent and EGFR-dependent.

FIGURE 1.

UTP time- and dose-dependent phosphorylation of ERK1/2 in HSG cells. A, representative Western blots of HSG cells serum-starved for 18 h and treated with or without UTP (100 μm) for the indicated times (left top panel) with the indicated UTP concentrations for 10 min (right top panel) at 37 °C. Protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for either p-ERK1/2 or ERK1/2. B, data are expressed as fold increases in ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by UTP, as compared with untreated control, and represent the means ± S.E. of results from five experiments. conc, concentration.

FIGURE 2.

The PKC inhibitor GF109303 attenuates rapid (1 min), but not slower and prolonged (10 min), UTP-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation. A, representative Western blots of HSG cells serum-starved for 18 h, pretreated for 30 min with or without the PKC inhibitor, GF109303 (10 μm), and then incubated with or without UTP (100 μm), the PKC activator phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, 1 μm), or EGF (10 ng/ml) for 1 or 10 min at 37 °C. The protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for either p-ERK1/2 or ERK1/2. B, data are expressed as percentages of maximal ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by UTP and represent the means ± S.E. of results from five experiments, where p < 0.001 (*) is a significant difference versus ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by UTP.

FIGURE 3.

The EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 attenuates slower and prolonged (10 min) UTP-induced p-ERK1/2 and EGFR phosphorylation but not rapid (1 min) UTP-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation. A and C, representative Western blots of HSG cells serum-starved for 18 h, pretreated for 30 min with or without the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 (10 μm), and then incubated with or without UTP (100 μm), HBEGF (10 ng/ml), or EGF (10 ng/ml) for the indicated time at 37 °C. The protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for either p-ERK1/2, p-EGFR, ERK1/2, or EGFR. E, representative Western blot of HSG cells serum-starved for 18 h and treated with or without UTP (100 μm) for the indicated times or with the indicated concentration of UTP for 10 min at 37 °C. The protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for p-EGFR. B, D, and F, data are expressed as percentages of maximal ERK1/2, EGFR or basal levels of EGFR phosphorylation induced by UTP and represent the means ± S.E. of results from three experiments, where p < 0.001 (*) is a significant difference versus ERK1/2 or EGFR phosphorylation induced by UTP.

EGFR and ERK1/2 Phosphorylation by UTP Is Src- independent

Previous studies determined that the P2Y2R contains two Src homology 3 domain-binding motifs in the C-terminal tail that mediate the Src-dependent phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and EGFR in human 1321N1 astrocytoma cells expressing the recombinant P2Y2R (44) and the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor in human coronary artery endothelial cells (39). Although Src is phosphorylated in HSG cells by P2Y2R activation (35), cells transfected with Src siRNAs did not block UTP-stimulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation at either the rapid (1 min) or the prolonged phase (10 min) of phosphorylation (Fig. 4). Additionally, Src siRNAs did not block UTP-induced EGFR phosphorylation (Fig. 4). These results indicate that Src is not involved in rapid or slow ERK1/2 or EGFR phosphorylation mediated by the P2Y2R. Thus, these data indicate the presence of a Src-independent mechanism of EGFR activation by the P2Y2R in HSG cells. The suppression of Src protein expression by Src siRNAs was confirmed by Western analysis with anti-Src (Fig. 4).

FIGURE 4.

UTP-induced ERK1/2 and EGFR phosphorylation is not dependent on Src kinase. Representative Western blots of HSG cells transfected with SMARTpool small interfering Src RNA (100 nm) using Lipofectamine 2000, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The cells transfected with nonspecific siRNA served as controls. Transfected cells were incubated with or without UTP (100 μm) or EGF (10 ng/ml) for the indicated time at 37 °C. The protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for either p-ERK1/2, p-EGFR, ERK1/2, or Src.

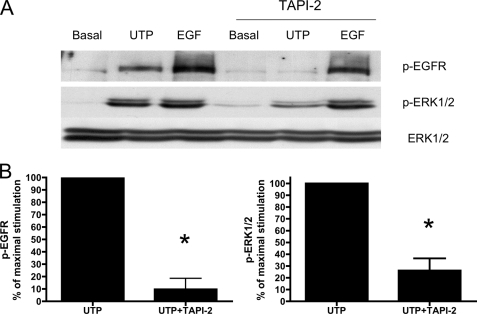

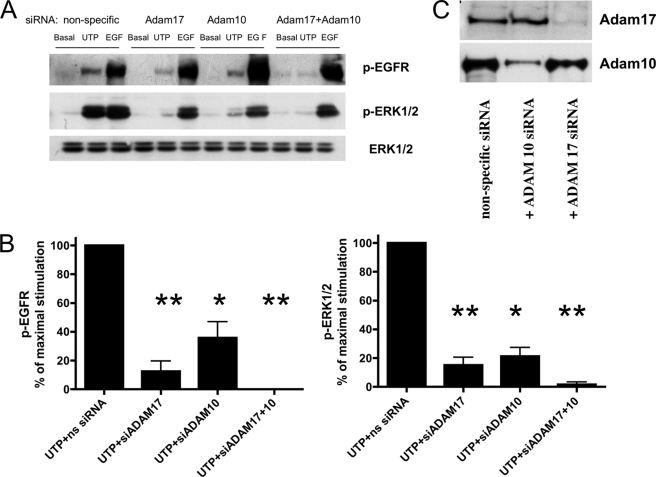

P2Y2R-mediated EGFR Phosphorylation Requires Metalloprotease Activity in HSG Cells

GPCRs have been shown to activate the EGFR through activation of metalloproteases that generate EGFR ligands (8, 20, 21). Therefore, the involvement of metalloprotease activation in P2Y2R-mediated EGFR phosphorylation was examined. TAPI-2, a selective inhibitor of the adamylsin (ADAM) family of metalloproteases, inhibited EGFR and ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by UTP (but not by EGF) in HSG cells (Fig. 5). There is evidence that specific subtypes of the ADAM family of metalloproteases, including ADAM10 and ADAM17, are involved in the shedding of EGF-like ligands (48, 57). ADAM10 and ADAM17 have been shown to be activated by P2Y2Rs (47). To determine the involvement of ADAM10 and ADAM17 in P2Y2R-mediated EGFR activation, HSG cells were transfected with small interfering RNA targeting either ADAM10 or ADAM17 mRNA. Transfection of HSG cells with ADAM10 or ADAM17 siRNA partially suppressed EGFR and ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by UTP, whereas co-transfection with both ADAM10 and ADAM17 siRNA almost completely prevented UTP-induced EGFR and ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 6, A and B), demonstrating that ADAM10 and ADAM17 are involved in P2Y2R-mediated EGFR activation leading to ERK1/2 phosphorylation. The suppression by siRNA of ADAM10 and ADAM17 protein expression in HSG cells was confirmed by Western analysis with ADAM10- and ADAM17-specific antibodies (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 5.

The metalloprotease inhibitor, TAPI-2, attenuates UTP-induced phosphorylation of EGFR and ERK1/2. A, representative Western blots of HSG cells serum-starved for 18 h, pretreated for 30 min with or without TAPI-2 (10 μm), and then incubated with or without UTP (100 μm) or EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min at 37 °C. The protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for either p-ERK1/2, p-EGFR, or ERK1/2. B, data are expressed as percentages of maximal EGFR or ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by UTP and represent the means ± S.E. of results from four experiments, where p < 0.001 (*) is a significant difference versus EGFR or ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by UTP.

FIGURE 6.

UTP-induced EGFR and ERK1/2 phosphorylation is dependent on ADAM17 and ADAM10. A, representative Western blots of HSG cells transfected with SMARTpool small interfering ADAM17 (ns) RNA (100 nm), ADAM10 RNA (100 nm), or both using Lipofectamine 2000, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The cells transfected with nonspecific (ns) siRNA served as controls. Transfected cells were incubated with or without UTP (100 μm) or EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min at 37 °C. The protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for p-ERK1/2, p-EGFR or ERK1/2. B, data are expressed as percentages of maximal EGFR or ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by UTP and represent the means ± S.E. of results from three experiments, where p < 0.01 (*) and p < 0.001 (**) are significant differences versus EGFR or ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by UTP and nonspecific siRNA. C, representative Western blots of HSG cells transfected with SMARTpool small interfering ADAM17 RNA (100 nm) and/or ADAM10 RNA (100 nm) or nonspecific siRNA. The protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for ADAM17 or ADAM10.

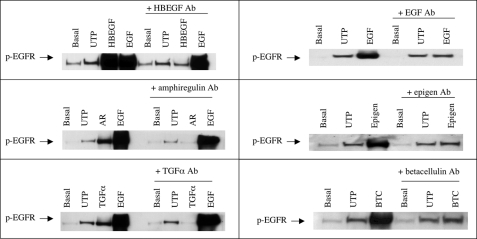

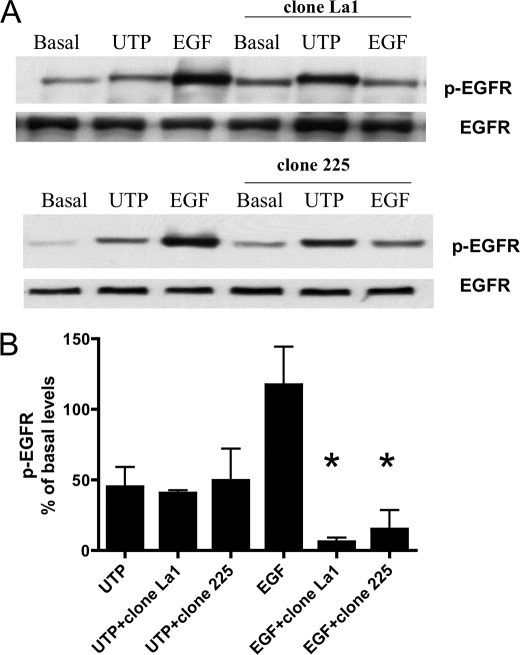

P2Y2R-induced EGFR Activation Is Independent of an EGFR Ligand in HSG Cells

To identify the EGFR ligand(s) cleaved by P2Y2R activation, we preincubated HSG cells with neutralizing antibodies against the six known EGFR ligands: HBEGF, TGFα, amphiregulin, betacellulin, epigen, or EGF for 60 min prior to UTP stimulation. Although these antibodies inhibited EGFR phosphorylation induced by the corresponding growth factors, they did not inhibit UTP-stimulated phosphorylation of EGFR (Fig. 7). Furthermore, incubation of HSG cells with anti-EGFR antibodies that block the extracellular EGFR ligand-binding domain, i.e. clones La1 and 225, did not prevent EGFR phosphorylation induced by UTP but was effective in inhibiting EGF-induced EGFR phosphorylation (Fig. 8). These data suggest that P2Y2R-mediated phosphorylation of EGFR is independent of ligand binding to the extracellular ligand-binding domain of EGFR.

FIGURE 7.

Neutralizing antibodies to EGFR ligands do not inhibit UTP-induced phosphorylation of the EGFR in HSG cells. Representative Western blots of HSG cells preincubated for 60 min with or without anti-HBEGF (40 μg/ml), anti-EGF (50 μg/ml), anti-amphiregulin (40 μg/ml), anti-epigen (50 μg/ml), anti-TGFα (20 μg/ml), or anti-betacellulin (20 μg/ml) antibody (Ab) and then incubated for 10 min with or without UTP (100 μm), HBEGF (20 ng/ml), EGF (10 ng/ml), amphiregulin (AR; 50 ng/ml), epigen (10 ng/ml), TGFα (3 ng/ml), or betacellulin (BTC; 100 ng/ml). The data shown are representative of results from three experiments.

FIGURE 8.

Antibodies that block the EGFR ligand-binding domain do not inhibit UTP-induced phosphorylation of EGFR. A, representative Western blots of HSG cells serum-starved for 18 h; pretreated for 30 min with or without the anti-EGFR antibodies, clone La1, or clone 225 (10 μm), and then incubated with or without UTP (100 μm) or EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min at 37 °C. The protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for either p-EGFR or EGFR. B, data are expressed as percentages of basal EGFR phosphorylation and represent the means ± S.E. of results from three experiments, where p < 0.001 (*) is a significant difference versus EGFR phosphorylation induced by EGF.

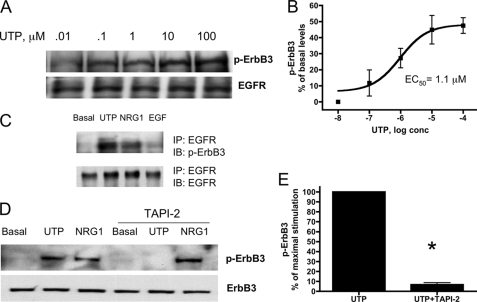

P2Y2R Activation Promotes the Formation of EGFR/ErbB3 Heterodimers in HSG Cells

EGFR phosphorylation can also be induced by heterodimerization with one of the other ErbB family members, ErbB2, ErbB3, or ErbB4. Because ErbB2 is a ligandless receptor, we postulated that ErbB3 is the likely dimerizing partner for EGFR. HSG cells do not express ErbB4 (data not shown), and UTP induced a dose-dependent increase in ErbB3 phosphorylation with an EC50 value of 1.1 μm (Fig. 9, A and B). Other results show that phosphorylated ErbB3 co-immunoprecipitated with EGFR after stimulation of HSG cells with either UTP or NRG1 but not with EGF (Fig. 9C), consistent with studies showing that EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimers are preferentially formed upon NRG binding to ErbB3 (58, 59). To determine whether UTP-induced ErbB3 phosphorylation is dependent on metalloprotease activity, HSG cells were treated with TAPI-2, similar to experiments on UTP-induced EGFR phosphorylation (Fig. 5). TAPI-2 attenuated UTP-induced phosphorylation of ErbB3 but not NRG1-induced phosphorylation of ErbB3 (Fig. 9, D and E). These results suggest that P2Y2R activation in HSG cells induces metalloprotease-dependent generation of NRG1 leading to phosphorylation of ErbB3. Because ErbB3 lacks intrinsic tyrosine kinase activity, heterodimerization with another member of the ErbB family is essential to initiate NRG-induced intracellular signaling (25), and therefore, ErbB3 likely forms a heterodimer with EGFR in HSG cells upon P2Y2R activation.

FIGURE 9.

UTP induces heterodimerization of EGFR and ErbB3 in HSG cells. A, representative Western blots of HSG cells serum-starved for 18 h and treated with the indicated concentration of UTP for 10 min at 37 °C. The protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for either p-ErbB3 or EGFR. B, dose response data are expressed as percentages of basal levels of ErbB3 phosphorylation and represent the means ± S.E. of results from three experiments. C, representative Western blots of HSG cells serum-starved for 18 h and then incubated with or without UTP (100 μm), NRG1 (10 ng/ml), or EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min at 37 °C. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-EGFR antibody, and the immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS-PAGE. EGFR immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted (IB) with anti-p-ErbB3 antibody or anti-EGFR antibody. D, HSG cells were serum-starved for 18 h, pretreated for 30 min with or without TAPI-2 (10 μm), and then incubated with or without UTP (100 μm) or NRG1 (10 ng/ml) for 10 min at 37 °C. The protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for either p-ErbB3 or ErbB3. E, data are expressed as percentages of maximal ErbB3 phosphorylation and represent the means ± S.E. of results from three experiments, where p < 0.001 (*) is a significant difference versus ErbB3 phosphorylation induced by UTP.

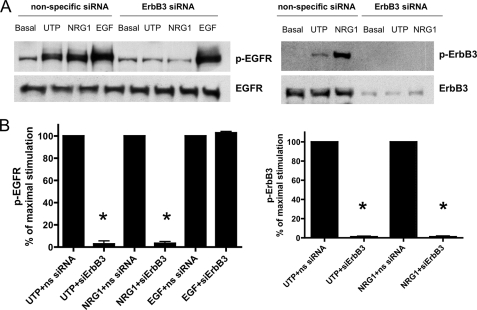

P2Y2R-mediated Phosphorylation of EGFR Is Dependent on ErbB3 and NRG1 Expression in HSG Cells

To further evaluate whether P2Y2R-mediated phosphorylation of EGFR is dependent on EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimer formation, HSG cells were transfected with ErbB3 siRNAs to inhibit expression of endogenous ErbB3. EGFR phosphorylation induced by UTP or NRG1, but not by EGF, was attenuated in HSG cells transfected with ErbB3 siRNAs (Fig. 10). ErbB3 phosphorylation induced by UTP or the ErbB3 ligand NRG1 was attenuated by silencing ErbB3 (Fig. 10), further supporting the conclusion that EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimers regulate EGFR/ErbB3 phosphorylation induced by UTP or NRG1. Because NRG is the only known ligand for ErbB3 and HSG cells express the subtype NRG1, it is postulated that NRG1 is the ligand generated by P2Y2R-mediated metalloprotease activation. In support of this hypothesis, UTP-induced phosphorylation of EGFR and ErbB3 was reduced in HSG cells treated with NRG1 siRNA (Fig. 11), indicating that NRG1 expression in HSG cells is required. The suppression of ErbB3 and NRG1 protein expression by ErbB3 and NRG1 siRNAs, respectively, in HSG cells was confirmed by Western analysis with anti-ErbB3 (Fig. 10A, right panel) and anti-NRG1 antibodies (Fig. 11A).

FIGURE 10.

UTP-induced phosphorylation of EGFR and ErbB3 is dependent on ErbB3 expression. A, representative Western blots of HSG cells transfected with SMARTpool small interfering ErbB3 RNA (100 nm) using Lipofectamine 2000, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The cells transfected with nonspecific (ns) siRNA served as controls. Transfected cells were incubated with or without UTP (100 μm), NRG1 (10 ng/ml), or EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min at 37 °C. The protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for either p-EGFR, EGFR, p-ErbB3, or ErbB3. B, data are expressed as a percentage of maximal EGFR or ErbB3 phosphorylation and represent the means ± S.E. of results from four experiments, where p < 0.001 (*) is a significant difference versus EGFR or ErbB3 phosphorylation induced by UTP or NRG1.

FIGURE 11.

UTP-induced phosphorylation of EGFR and ErbB3 is dependent on NRG1 expression. A, representative Western blots of HSG cells transfected with SMARTpool small interfering NRG1 RNA (100 nm) using Lipofectamine 2000, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The cells transfected with nonspecific siRNA served as controls. Transfected cells were incubated with or without UTP (100 μm), NRG1 (10 ng/ml), or EGF (10 ng/ml) for 10 min at 37 °C. The protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for either p-EGFR, EGFR, p-ErbB3, ErbB3, or NRG1. B, data are expressed as percentages of maximal EGFR or ErbB3 phosphorylation and represent the means ± S.E. of results from three experiments, where p < 0.01 (*) is a significant difference versus EGFR or ErbB3 phosphorylation induced by UTP.

EGFR and ErbB3 Phosphorylation Induced by UTP Occurs in SMG Cells from wt but Not P2Y2R−/− Mice

To verify that UTP-induced EGFR and ErbB3 phosphorylation was mediated by the P2Y2R in primary salivary gland acinar cells, we examined whether these responses occur in cells isolated from the SMG of P2Y2R−/− mice, in comparison with wt controls. Primary acinar cells were prepared from freshly isolated SMGs obtained from wt and P2Y2R−/− mice and cultured for 72 h to enhance P2Y2R expression in wt SMG cells, as previously described (32). The results show that primary SMG cells from wt and P2Y2R−/− mice express EGFR and ErbB3 that are activated by their respective ligands, EGF and NRG1 (Fig. 12). Furthermore, UTP induced phosphorylation of EGFR and ErbB3 in primary SMG acinar cells from wt but not P2Y2R−/− mice (Fig. 12). These data support the conclusion that P2Y2Rs mediate UTP-induced EGFR and ErbB3 activation in primary salivary gland cells. These data suggest that P2Y2Rs that are known to be up-regulated in salivary gland acinar cells in response to stress or disease (32–34) may be useful to promote salivary gland regeneration using P2Y2R ligands (i.e. UTP or ATP), which activate growth factor receptors that regulate salivary gland growth and differentiation (47, 76).

FIGURE 12.

P2Y2R activation causes phosphorylation of EGFR and ErbB3 in SMG cells from wild type but not P2Y2R−/− mice. Representative Western blots of SMG cells from wt C57BL/6 and C57BL/6 P2Y2R−/− mice. SMGs were isolated, enzymatically dispersed, and cultured for 72 h, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Then cell aggregates were serum-starved for 18 h and UTP (100 μm), EGF (10 ng/ml), or NRG1 (10 ng/ml) was added for 5 or 10 min at 37 °C. The protein extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for p-EGFR, p-ErbB3, EGFR, and ErbB3. The data shown are representative of results from three experiments.

DISCUSSION

Activation of the P2Y2R by its agonists ATP or UTP induces the Gαq/11-mediated stimulation of phospholipase C, thereby generating the second messengers inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol that serve to increase calcium release from intracellular stores and activate PKC, respectively (30, 31). Independent of Gq/11 protein, P2Y2Rs have been shown to activate growth factor receptors, integrins, and their signaling pathways, thereby stimulating intracellular kinases including MAPK/ERK1/2 that regulate cell survival, differentiation, wound healing, and tissue regeneration (38, 41, 60, 61). The results of the current study demonstrate that activation of P2Y2Rs in HSG cells stimulates ERK1/2 phosphorylation via two distinct pathways: a rapid PKC-dependent pathway and a slower and prolonged EGFR-dependent pathway. Because PKC is involved in the rapid phase of UTP-induced ERK1/2 activation in HSG cells (Fig. 2), it is likely that P2Y2Rs regulate this pathway via Gαq/11-mediated activation of phospholipase C (30, 31). In addition, activation of phospholipase C by P2Y2Rs has been well described to regulate ion (Cl−) transport in epithelial cells via intracellular calcium mobilization (62–64). A recent study with human endometrial stromal cells indicates that P2Y2R activation of the phospholipase C/PKC/ERK signaling pathway leads to the induction of early growth response factor-1 (65), a transcription factor known to mediate cell growth and differentiation and tissue repair (66, 67). Thus, activation of this pathway by P2Y2Rs that have been shown to be up-regulated in damaged or diseased salivary glands (32–34) may play a similar role in tissue repair.

The slower and prolonged (10 min) ERK1/2 phosphorylation induced by UTP is independent of PKC but is dependent on the activation of EGFR tyrosine kinase (Fig. 3). Activation of growth factor receptors is a common mechanism by which GPCRs signal to ERK1/2, and numerous signaling pathways have been proposed to explain this phenomenon (2, 8, 20, 68). Many studies have implicated Src kinases in the activation of growth factor receptors by GPCRs (12, 69) including the P2Y2R (39, 44). However, the current study demonstrates that inhibition of Src kinase activity (data not shown) or suppression of Src expression (Fig. 4) had no effect on P2Y2R-mediated ERK1/2 or EGFR phosphorylation in HSG cells. These data are consistent with our previous studies with HSG cells indicating that the P2Y2R regulates the expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 by a Src-independent activation of EGFR (35). P2Y2Rs also have been shown to activate ERK1/2 signaling through interaction with integrins via a RGD motif in their first extracellular loop (45). However, preincubation of HSG cells with an RGD-containing peptide did not inhibit UTP-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 or EGFR in HSG cells (data not shown). Integrin activation of cell signaling pathways depends on integrin interactions with extracellular matrix proteins (70). The current studies were performed with HSG cells grown on plastic without the presence of extracellular matrix. Therefore, further studies will be needed to determine whether P2Y2R-mediated signaling via integrins can regulate ERK1/2 and EGFR phosphorylation in the presence of extracellular matrices known to influence salivary gland differentiation (52, 71, 72).

Numerous studies have shown that EGFR activation by GPCRs occurs through metalloprotease-dependent shedding of an EGFR ligand (for a review see Ref. 21), resulting in homodimerization of EGFR and activation of its downstream signaling pathways. Members of the adamylsin family, ADAM10 and ADAM17, have emerged as the main sheddases that catalyze the release of membrane-bound EGFR ligands (48). Because we recently reported that activation of the P2Y2R expressed in 1321N1 astrocytoma cells stimulates ADAM10 and ADAM17 activities, resulting in the cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (47), we initially hypothesized that P2Y2R activation in HSG cells causes the shedding of an EGFR ligand. The phosphorylation of EGFR by P2Y2R activation was not the result of the release of an EGFR ligand, because neutralizing antibodies to known EGFR ligands had no effect on UTP-induced EGFR phosphorylation, although they did prevent EGFR phosphorylation induced by the relevant EGFR ligand (Fig. 7). Furthermore, antibodies that block the EGFR ligand-binding site did not inhibit UTP-induced phosphorylation of EGFR (Fig. 8), indicating that an alternative mechanism of P2Y2R-mediated EGFR phosphorylation besides the release of EGFR ligands occurs in HSG cells. It has been shown that the EGFR can be activated by heterodimerization with another member of the ErbB receptor family, including ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4 (24). Although ErbB2 is the preferred heterodimeric partner for EGFR, particularly in malignant tumors (26–28), ErbB2 is a ligandless receptor, and therefore, the activation of EGFR/ErbB2 heterodimers requires the presence of an EGFR ligand. The EGFR can also dimerize with ErbB3 or ErbB4 upon activation by the ligand NRG, another membrane-bound growth factor cleaved by metalloproteases, including ADAM10 and ADAM17 (50, 73). The current study suggests that in HSG cells, P2Y2R activation induces the formation of EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimers (Fig. 9C) via metalloprotease-dependent (Fig. 9, D and E) NRG1 shedding (Fig. 11) resulting from the UTP dose-dependent phosphorylation of both EGFR (Fig. 3, E and F) and ErbB3 (Fig. 9, A and B). Because ErbB3 has impaired tyrosine kinase activity, ErbB3 must associate with another member of the EGF receptor family to become phosphorylated by NRG (25). Once activated, EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimers couple to the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt (serine/threonine-specific protein kinase) pathway (74). The physiological consequences of EGFR/ErbB3 heterodimer formation are still unclear; however, it appears to promote growth of pancreatic (75) and breast (76) cancers and melanoma (59). The HSG cells used for this study were derived from a malignant salivary gland tumor, suggesting that P2Y2Rs may contribute to salivary gland tumor growth.

Although the ErbB family is recognized for its aberrant signaling in cancer, these receptors also play essential roles in embryonic development, cell homeostasis, wound healing, inflammation, and tissue regeneration (29, 77, 78). Salivary gland branching morphogenesis is dependent on ErbB family members and their ligands (see review in Ref. 51), including the ErbB3 ligand NRG (54) and the ErbB3 downstream signaling pathway phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt (79). Although P2Y2Rs do not appear to be expressed during salivary gland development,4 our previous studies have shown that the P2Y2R is barely detectable in normal salivary glands but is up-regulated upon disruption of tissue homeostasis by enzymatic dispersal and culture of rat salivary glands as a function of time (32). Here, we show that P2Y2R activation with UTP in primary SMG cells from wild type mice induces the phosphorylation of EGFR and ErbB3 (Fig. 12). In contrast, UTP has no effect on EGFR or ErbB3 phosphorylation in primary SMG cells isolated from P2Y2R−/− mice (Fig. 12), conclusively demonstrating that the responses to UTP are mediated by P2Y2R expression. Additionally, P2Y2R up-regulation occurs in vivo in response to SMG duct ligation, and its expression returns to basal levels after deligation (33), suggesting that P2Y2Rs may play a role in salivary gland regeneration. Furthermore, the P2Y2R is up-regulated in a mouse model of autoimmune exocrinopathy that has characteristics similar to human Sjögren's syndrome (34), possibly contributing to the associated inflammatory response (35). The physiological or pathophysiological roles for P2Y2Rs in salivary glands are still unclear; however, several studies have shown that P2Y2Rs are critical for cell survival, differentiation, wound healing, liver regeneration, and intimal hyperplasia in blood vessels (36–41). A recent study proposes that P2Y2R up-regulation in the epithelial cells in inflammatory bowel disease is proinflammatory in the acute phase of inflammation then enhances epithelial repair in the resolution phase following inflammation (42). Therefore, it is possible that expression and activation of P2Y2Rs in damaged or diseased salivary glands may serve to regulate the same processes.

A. M. Ratchford, O. J. Baker, J. M. Camden, S. Rikka, M. J. Petris, C. I. Seye, L. Erb, and G. A. Weisman, unpublished observations.

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- P2Y2R

- P2Y2 nucleotide receptor

- HBEGF

- heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor

- HSG

- human salivary gland

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- TAPI-2

- tumor necrosis factor-α protease inhibitor

- EGFR

- epidermal growth factor receptor

- ADAM

- a disintegrin and metalloprotease

- NRG1

- heregulin/neuregulin-1

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NRG

- heregulin/neuregulin

- TGF

- transforming growth factor

- SMG

- submandibular gland

- wt

- wild type

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hsieh M., Conti M. (2005) Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 16, 320–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pierce K. L., Premont R. T., Lefkowitz R. J. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 639–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukuhara S., Chikumi H., Gutkind J. S. (2001) Oncogene 20, 1661–1668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dhanasekaran N., Heasley L. E., Johnson G. L. (1995) Endocr. Rev. 16, 259–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Biesen T., Luttrell L. M., Hawes B. E., Lefkowitz R. J. (1996) Endocr. Rev. 17, 698–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luttrell L. M., Della Rocca G. J., van Biesen T., Luttrell D. K., Lefkowitz R. J. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 4637–4644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhola N. E., Grandis J. R. (2008) Front. Biosci. 13, 1857–1865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daub H., Wallasch C., Lankenau A., Herrlich A., Ullrich A. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 7032–7044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.New D. C., Wong Y. H. (2007) J. Mol. Signal. 2, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ohtsu H., Dempsey P. J., Eguchi S. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 291, C1–C10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsai W., Morielli A. D., Peralta E. G. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 4597–4605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soltoff S. P. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 23110–23117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keely S. J., Calandrella S. O., Barrett K. E. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 12619–12625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dikic I., Tokiwa G., Lev S., Courtneidge S. A., Schlessinger J. (1996) Nature 383, 547–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zwick E., Daub H., Aoki N., Yamaguchi-Aoki Y., Tinhofer I., Maly K., Ullrich A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 24767–24770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keely S. J., Uribe J. M., Barrett K. E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 27111–27117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frank G. D., Eguchi S. (2003) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 5, 771–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frank G. D., Mifune M., Inagami T., Ohba M., Sasaki T., Higashiyama S., Dempsey P. J., Eguchi S. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 1581–1589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohtsu H., Frank G. D., Utsunomiya H., Eguchi S. (2005) Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7, 1315–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prenzel N., Zwick E., Daub H., Leserer M., Abraham R., Wallasch C., Ullrich A. (1999) Nature 402, 884–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pierce K. L., Luttrell L. M., Lefkowitz R. J. (2001) Oncogene 20, 1532–1539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalmes A., Vesti B. R., Daum G., Abraham J. A., Clowes A. W. (2000) Circ. Res. 87, 92–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schlessinger J. (2000) Cell 103, 211–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jorissen R. N., Walker F., Pouliot N., Garrett T. P., Ward C. W., Burgess A. W. (2003) Exp. Cell Res. 284, 31–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Warren C. M., Landgraf R. (2006) Cell. Signal. 18, 923–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Citri A., Yarden Y. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 505–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olayioye M. A., Neve R. M., Lane H. A., Hynes N. E. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 3159–3167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hynes N. E., Lane H. A. (2005) Nat. Rev. Cancer 5, 341–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Holbro T., Hynes N. E. (2004) Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 44, 195–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boarder M. R., Weisman G. A., Turner J. T., Wilkinson G. F. (1995) Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 16, 133–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weisman G. A., Turner J. T., Fedan J. S. (1996) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 277, 1–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turner J. T., Weisman G. A., Camden J. M. (1997) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 273, C1100–C1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahn J. S., Camden J. M., Schrader A. M., Redman R. S., Turner J. T. (2000) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 279, C286–C294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schrader A. M., Camden J. M., Weisman G. A. (2005) Arch. Oral Biol. 50, 533–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker O. J., Camden J. M., Rome D. E., Seye C. I., Weisman G. A. (2008) Mol. Immunol. 45, 65–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dixon C. J., Bowler W. B., Littlewood-Evans A., Dillon J. P., Bilbe G., Sharpe G. R., Gallagher J. A. (1999) Br. J. Pharmacol. 127, 1680–1686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mediero A., Peral A., Pintor J. (2006) Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47, 4500–4506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crooke A., Mediero A., Guzmán-Aránguez A., Pintor J. (2009) Mol. Vis. 15, 1169–1178 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seye C. I., Yu N., González F. A., Erb L., Weisman G. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35679–35686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seye C. I., Yu N., Jain R., Kong Q., Minor T., Newton J., Erb L., González F. A., Weisman G. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 24960–24965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beldi G., Wu Y., Sun X., Imai M., Enjyoji K., Csizmadia E., Candinas D., Erb L., Robson S. C. (2008) Gastroenterology 135, 1751–1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Degagné E., Grbic D. M., Dupuis A. A., Lavoie E. G., Langlois C., Jain N., Weisman G. A., Sévigny J., Gendron F. P. (2009) J. Immunol. 183, 4521–4529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Elliott M. R., Chekeni F. B., Trampont P. C., Lazarowski E. R., Kadl A., Walk S. F., Park D., Woodson R. I., Ostankovich M., Sharma P., Lysiak J. J., Harden T. K., Leitinger N., Ravichandran K. S. (2009) Nature 461, 282–286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu J., Liao Z., Camden J., Griffin K. D., Garrad R. C., Santiago-Pérez L. I., González F. A., Seye C. I., Weisman G. A., Erb L. S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8212–8218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Erb L., Liu J., Ockerhausen J., Kong Q., Garrad R. C., Griffin K., Neal C., Krugh B., Santiago-Pérez L. I., González F. A., Gresham H. D., Turner J. T., Weisman G. A. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 153, 491–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang M., Kong Q., Gonzalez F. A., Sun G., Erb L., Seye C., Weisman G. A. (2005) J. Neurochem. 95, 630–640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Camden J. M., Schrader A. M., Camden R. E., González F. A., Erb L., Seye C. I., Weisman G. A. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 18696–18702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sahin U., Weskamp G., Kelly K., Zhou H. M., Higashiyama S., Peschon J., Hartmann D., Saftig P., Blobel C. P. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 164, 769–779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Falls D. L. (2003) Exp. Cell Res. 284, 14–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou B. B., Peyton M., He B., Liu C., Girard L., Caudler E., Lo Y., Baribaud F., Mikami I., Reguart N., Yang G., Li Y., Yao W., Vaddi K., Gazdar A. F., Friedman S. M., Jablons D. M., Newton R. C., Fridman J. S., Minna J. D., Scherle P. A. (2006) Cancer Cell 10, 39–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patel V. N., Rebustini I. T., Hoffman M. P. (2006) Differentiation 74, 349–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoffman M. P., Kibbey M. C., Letterio J. J., Kleinman H. K. (1996) J. Cell Sci. 109, 2013–2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zheng C., Hoffman M. P., McMillan T., Kleinman H. K., O'Connell B. C. (1998) J. Cell. Physiol. 177, 628–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miyazaki Y., Nakanishi Y., Hieda Y. (2004) Dev. Dyn. 230, 591–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Parr C. E., Sullivan D. M., Paradiso A. M., Lazarowski E. R., Burch L. H., Olsen J. C., Erb L., Weisman G. A., Boucher R. C., Turner J. T. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 3275–3279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soltoff S. P., Avraham H., Avraham S., Cantley L. C. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2653–2660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Edwards D. R., Handsley M. M., Pennington C. J. (2008) Mol. Aspects Med. 29, 258–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li Z., Mei Y., Liu X., Zhou M. (2007) Cell. Signal. 19, 466–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ueno Y., Sakurai H., Tsunoda S., Choo M. K., Matsuo M., Koizumi K., Saiki I. (2008) Int. J. Cancer 123, 340–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arthur D. B., Georgi S., Akassoglou K., Insel P. A. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 3798–3804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arthur D. B., Akassoglou K., Insel P. A. (2006) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 347, 678–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knowles M. R., Clarke L. L., Boucher R. C. (1992) Chest 101, 60S–63S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Turner J. T., Redman R. S., Camden J. M., Landon L. A., Quissell D. O. (1998) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 275, C367–C374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Noone P. G., Bennett W. D., Regnis J. A., Zeman K. L., Carson J. L., King M., Boucher R. C., Knowles M. R. (1999) Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 160, 144–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chang S. J., Tzeng C. R., Lee Y. H., Tai C. J. (2008) Cell. Signal. 20, 1248–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shin S. Y., Lee J. H., Min B., Lee Y. H. (2006) Exp. Mol. Med. 38, 677–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moon Y., Yang H., Kim Y. B. (2007) Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 223, 155–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fischer O. M., Hart S., Gschwind A., Ullrich A. (2003) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 31, 1203–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McCole D. F., Keely S. J., Coffey R. J., Barrett K. E. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42603–42612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hood J. D., Cheresh D. A. (2002) Nat. Rev. Cancer 2, 91–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hoffman M. P., Nomizu M., Roque E., Lee S., Jung D. W., Yamada Y., Kleinman H. K. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 28633–28641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hoffman M. P., Kidder B. L., Steinberg Z. L., Lakhani S., Ho S., Kleinman H. K., Larsen M. (2002) Development 129, 5767–5778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Witters L., Scherle P., Friedman S., Fridman J., Caulder E., Newton R., Lipton A. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 7083–7089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim H. H., Vijapurkar U., Hellyer N. J., Bravo D., Koland J. G. (1998) Biochem. J. 334, 189–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Frolov A., Schuller K., Tzeng C. W., Cannon E. E., Ku B. C., Howard J. H., Vickers S. M., Heslin M. J., Buchsbaum D. J., Arnoletti J. P. (2007) Cancer Biol. Ther. 6, 548–554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang C., Liu Y., Lemmon M. A., Kazanietz M. G. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 831–842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Berasain C., Castillo J., Perugorria M. J., Latasa M. U., Prieto J., Avila M. A. (2009) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1155, 206–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bersell K., Arab S., Haring B., Kühn B. (2009) Cell 138, 257–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Larsen M., Hoffman M. P., Sakai T., Neibaur J. C., Mitchell J. M., Yamada K. M. (2003) Dev. Biol. 255, 178–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]