Abstract

Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are pluripotent cells able to grow indefinitely in culture and to differentiate into all cell types of embryos upon specific stimuli. Molecular mechanisms controlling the unique characteristics of ESCs are still largely unknown. We identified Dies1 (Differentiation of ESCs 1), an unpublished gene, that encodes a type I membrane protein. ESCs stably transfected with Dies1 small hairpin RNAs failed to properly differentiate toward neural and cardiac cell fate upon appropriate stimuli and continued to express markers of undifferentiated cells, such as the membrane-associated alkaline phosphatase, and transcription factors, like Oct3/4 and Nanog, when grown under conditions promoting differentiation. Our results demonstrated that Dies1 is required for BMP4/Smad1 signaling cascade; in undifferentiated ESCs Dies1 knockdown did not affect the expression of leukemia inhibitory factor downstream targets, whereas it resulted in a strong decrease of BMP4 signaling, as demonstrated by the decrease of Id1, -2, and -3 mRNAs, the decreased activity of Id1 gene promoter, and the reduced phospho-Smad1 levels. Dies1 knockdown had no effect in murine ESCs when the expression of the BMP4 receptor Alk3 was suppressed. The phenotype induced by Dies1 suppression in ESCs is due to the indirect activation of the Nodal/Activin pathway, which is a consequence of the BMP4 pathway inhibition and is sufficient to support the mESC undifferentiated state in the absence of leukemia inhibitory factor.

Keywords: Cell/Stem, Development Differentiation/Stem Cell, Signal Transduction, shRNA, Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP), BMP4, Nodal/Activin, Gene Silencing

Introduction

Detailed understanding of the molecular mechanisms responsible for embryonic stem cell (ESC)2 pluripotency and self-renewal is of crucial importance to develop in the future efficient procedures to realize their therapeutic promises. Several transcription factors and chromatin remodeling enzymes form a regulatory circuitry that allows ESCs to maintain their phenotype when propagated in vitro (1, 2). This complex transcriptional machinery is under the control of robust self-regulatory loops; for example, master genes of stemness such as Oct3/4, Nanog, and Sox2 encode transcription factors that regulate a wide array of genes, including themselves (3, 4). This transcription apparatus is also regulated by environmental signals. The first extracellular factor that was demonstrated to be necessary to maintain indefinitely the ESCs in culture is the leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), a cytokine of the interleukin-6 family (5). It activates a dimeric membrane receptor (LIFR-gp130), which mainly works by activating the transcription factor STAT3 (6, 7). To enable propagation of ESCs in the undifferentiated state, LIF is not sufficient, and serum is also required. A few years ago, Ying et al. (8) demonstrated that bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) 4 is necessary to maintain ESCs in the undifferentiated phenotype in vitro. BMPs belong to the TGFβ family of proteins; these molecules control a variety of functions in cells and tissues, from proliferation to differentiation and apoptosis (9). At present, TGFβ family members such as Activin, Nodal, and BMPs are well known to play a key role in the modulation of stem cell self-renewal and proliferation (10). BMP4, like the other members of the family, acts by binding type I (e.g. Alk3, Alk6, and Alk2) and type II (BMPRII, ActRIIA, and ActRIIB) receptors. Upon BMP binding to these membrane proteins, type II receptors phosphorylate type I receptors that in turn phosphorylate cytosolic Smad proteins (Smad1, -5, and/or -8). Phosphorylated Smads bind to their co-factor Smad4, and the complex translocates into the nucleus where it regulates gene expression. The same Smad4 is also a co-factor of Smad2 and -3, which transduce signals mediated by TGFβ family members such as Nodal or Activin (11).

Modulation of TGFβ and BMP signaling events appears to be of crucial importance, because a complex regulatory mechanism, including secreted soluble proteins such as Noggin, Chordin, Follistatin, and Gremlin or membrane proteins such as Betaglycan, Cripto, and RGMs (12), is responsible for this modulation.

BMP4 is able to sustain mouse ESC pluripotency by inducing the transcription of the Id genes (Id1–3) through Smad activation, thus inhibiting ESC differentiation toward neuroectodermal derivatives (8). Other results indicate that this BMP4 activity is also dependent on the inhibition of the MAPK pathway (13, 14), whose activation is necessary for the differentiation process, and on the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Wnt1 pathways (15). On the other hand, the Activin-Nodal pathway is involved in mouse ESC propagation (16) and in maintaining pluripotency in human ESCs and in mouse epiblast stem cells, by modulating Nanog expression (17). Moreover, the Activin-Nodal pathway is sufficient to maintain ESCs in an undifferentiated state in the absence of LIF when the E-cadherin gene is suppressed (18). Here, we report the identification and characterization of the membrane protein Dies1, which is required for the transition of mESCs from the undifferentiated to differentiated state and necessary for the proper function of the BMP4 signaling pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture and Transfection

E14Tg2a mouse ES cells were cultured as described previously (26). Neural differentiation was induced as described previously (19) in the following medium (neural differentiation medium): knock-out Dulbecco's minimal essential medium supplemented with 10% knock-out serum replacement (both from Invitrogen), 0.1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mm glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin/streptomycin. The hanging drop method used to differentiate ESCs was as described previously (20). Generation and culture of the α1tub-GFP cell line have been described previously (19). Transfection of the small interfering RNA smart pools (Dharmacon), shRNA (Open Biosystems Mouse pSM2 retroviral shRNA mir), and plasmids was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. Activin receptor-like kinase inhibitor SB-431542 (Sigma) was used at a concentration of 10 μm. BMP4 (R & D Systems) was used at concentration of 20 ng/ml. Firefly and Renilla luciferase activities were measured with the Dual-Luciferase® reporter system (Promega) 24 h post-transfection by using a Sirius luminometer (Berthold Detection Systems). The data are expressed as relative values compared with nonsilencing transfected cells, after normalization with Renilla luciferase activity.

Plasmids and RNA Interference

Sequences of shRNA used are as follows: Dies sh1 (Open Biosystems), TGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGAGGAACCCTGCTCCTTGCTATTTAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTAAATAGCAAGGAGCAGGGTTCCCTGCCTACTGCCTCGGA; Dies sh2 (generated following Open Biosystems protocol available on line), TGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGCGGAACCACTGTGAGCTCATTATAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTATAATGAGCTCACAGTGGTTCCTTGCCTACTGCCTCGGA; and Id1 shRNA sequence (Open Biosystems), TGCTGTTGACAGTGAGCGCGCAGCATGTAATCGACTACATTAGTGAAGCCACAGATGTAATGTAGTCGATTACATGCTGCATGCCTACTGCCTCGGA.

Dies1 full-length (National Institutes of Health Mammalian Gene Collection, Invitrogen clone IMAGE 3488482) and Dies1 extracellular domain (ECD) (amino acids 1–189) cDNA were cloned in pCBA-GFP vector (19), by replacing green fluorescent protein. 3×FLAG sequence was inserted at the 3′end of both Dies1 full-length and Dies1 ECD cDNAs. The following oligonucleotides were used: HindIII 3×FLAG, AGCTTGACTACAAAGACCATGACGGTGATTATAAAGATCATGATATCGATTACAAGGATGACGATGACAAGTAAGC; NotI reverse 3×FLAG, GGCCGCTTACTTGTCATCGTCATCCTTGTAATCGATATCATGATCTTTATAATCACCGTCATGGTCTTTGTAGTCA; 5′BamHI Dies1 full-length forward, GGATCCGCCGCCATGGGTGTCCCCGCGGTCCCAGAGGCCAGC; 3′NotI/HindIII Dies1 full-length reverse, GCGGCCGCAAGCTTTTAGATGGCTTCAGAGTTAGGGGAGTCAG; 5′BamHI Dies1 ECD forward, GGATCCGCCGCCATGGGTGTCCCCGCGGTCCCAGAGGCCAGC; 3′HindIII Dies1 ECD reverse, AAGCTTTTACGTGATGCTGTCACTGTCCTGCTCATTAGACG. Strep-tag sequence was inserted at 3′end of Dies1 ECD using the following nucleotides: HindIII StrepTag forward, CTTCTCAAATTGTGGGTGGCTCCAGCCGCCGCCTAAGC, and NotI StrepTag reverse, TTAGGCGGCGGCTGGAGCCACCCACAATTTGAGAAGA.

RNA Isolation, Reverse Transcription, and Real Time PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted by using TRIzol ultra pure reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed with SuperScript Vilo (Invitrogen). Real time reverse transcription-PCR was carried out with ABI PRISM 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) using Power SYBR Green PCR master mix (Applied Biosystems). Gene-specific primers used for amplification are listed in supplemental Table 1. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase was used to normalize samples.

Western Blot and Immunofluorescence

The following antibodies were used for Western blot analysis: anti-Nanog (Calbiochem), anti Oct3/4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Rabbit polyclonal Dies1-specific antibody was raised against the polypeptide ELKNHHPEQRFYGSM (PickCell Laboratories). Immunofluorescence was performed as described previously (19). Primary antibodies were used at the following working dilutions: βIII-tubulin (1:400; Sigma), Oct3/4 (1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Nanog (1:100, Calbiochem), and FLAG (1:300 Sigma). Secondary antibodies were from Molecular Probes. Images were captured with an inverted microscope (DMI4000, Leica Microsystems) and with a confocal microscope (LSM 510 META, Zeiss).

Teratoma Formation

Nude mice were injected subcutaneously with 2 × 106 ESC cells transfected with Dies1 shRNA (left side) or NS shRNA (right side). Four weeks after the injection, tumors were surgically dissected from the mice. Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed by using Delfia EU labeling kit (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 96-well plates Strep-MAB-Immunocoated (IBA) were incubated at 4 °C for multiple rounds with the conditioned medium of HEK293 cells secreting Strep-tagged Dies1 ECD. Then 100 ng/ml BMP4 (R & D Systems), marked with Europium (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), was added to the wells and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. For competition assay, some wells were pretreated with unlabeled BMP4 at the reported concentration. Fluorescence signal was detected with Envision 2102 Multilabel Reader (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

RESULTS

Suppression of Dies1 Gene by RNA Interference Blocks ESC Differentiation

The screening of a large collection of shRNAs allowed us to identify numerous genes whose suppression by RNA interference resulted in the failure of mouse ESC differentiation in vitro. Some of these genes were still unannotated; we named them Dies (Differentiation of ESC). The readout of this screening was based on the evaluation of the EGFP signal upon the induction of differentiation in an E14Tg2a cell line stably expressing EGFP under the control of the neuron-specific α1-tubulin gene promoter (α1-tub-GFP) (19).

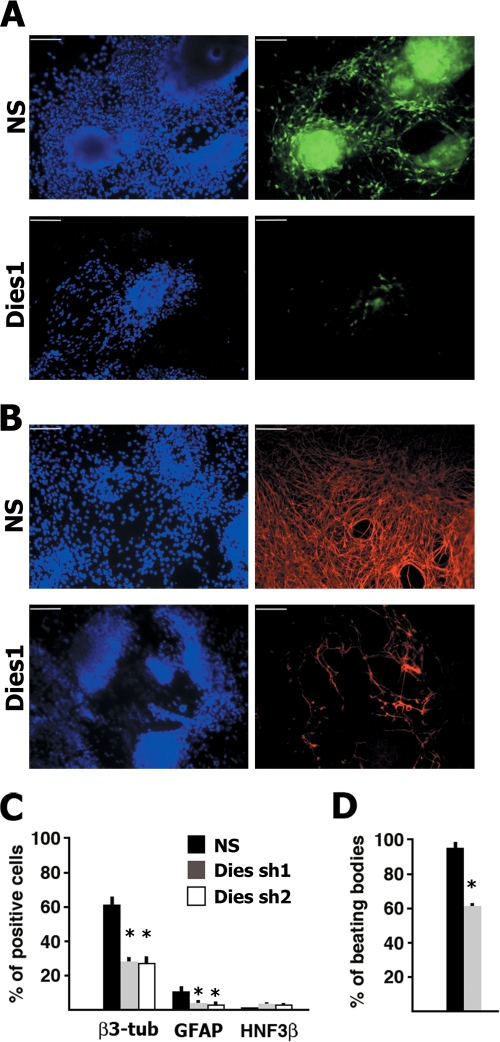

As shown in Fig. 1 A, most of the control α1-tub-GFP ESCs, transfected with a nonsilencing (NS) shRNA, expressed high levels of EGFP when grown for 13 days in neural differentiation medium (see under “Materials and Methods”). In contrast, only a few cells transfected with the shRNA (Dies sh1) targeting Dies1 (Riken cDNA 4632428N05) showed an EGFP signal. The result was confirmed in wild type E14Tg2a ESCs, induced to differentiate in the same conditions as the α1-tub-GFP cells. About 60% of the cells transfected with the NS shRNA, grown 13 days in differentiation medium, were positive to β3-tubulin antibody (neuron-specific) versus only 30% of the cells transfected with the Dies1 targeting shRNA (Fig. 1, B and C). Similarly, glial fibrillary acidic protein-positive cells decreased from 12% in NS transfected cells to 4% in Dies1 knockdown (KD) cells (Fig. 1C). Moreover, rare HNF3β (endoderm) and no Brachyury (mesoderm)-positive cells were seen (Fig. 1C). Dies1 suppression was assessed by Western blot with a Dies1-specific antibody (see supplemental Fig. 1). Identical results were obtained by targeting Dies1 with a second independent shRNA (Dies sh2).

FIGURE 1.

Dies1 silencing impairs mouse ESC differentiation. A, E14 mouse ESCs stably transfected with a construct driving the expression of EGFP under the control of the neuron-specific α1-tubulin gene promoter were transfected with an shRNA targeting the Dies1 gene. 13 days after the induction of differentiation, ESCs transfected with the nonsilencing (NS) shRNA showed many cells expressing EGFP (upper right panel), although Dies1 suppressed cells did not (lower right panel). Scale bars, 100 μm. B, E14Tg2A ESCs were transfected with the shRNA targeting Dies1. 13 days after the induction of differentiation, ESCs transfected with the control NS shRNA showed most of the cells expressing β3-tubulin (upper right panel), whereas only a few Dies1 KD cells were decorated by the β3-tubulin antibody. C, mouse ESCs were transfected with NS shRNA (black bars) or with two different shRNAs targeting Dies1 (Dies sh1, gray bars, and Dies sh2, white bars). 13 days after the induction of the differentiation, cells were stained with various antibodies, and positive cells were counted. The histogram reports the percentages of cells positive for antibodies recognizing the neuron-specific β3-tubulin (β3-tub), glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and hepatocyte nuclear factor 3β (HNF3β). Values are the means of three independent experiments plus S.D. *, p ≤ 0.001. D, mouse ESCs transfected with NS (black bar) or with Dies sh1 (gray bar) were cultured as embryoid bodies in a selected serum for 8 days to obtain differentiation into cardiomyocytes. The percentage of embryoid bodies containing spontaneously contracting clusters (beating hearts) was measured in three independent experiments. S.D. is indicated. *, p ≤ 0.001.

We then explored Dies1 involvement in ESC differentiation by inducing differentiation toward cardiomyocytes. ESCs were induced to differentiate into cardiomyocytes using the hanging drop procedure (20). Similar to that observed in the monolayer cultures, the number of embryoid bodies containing spontaneously contracting clusters of cells (beating cardiomyocytes) was greatly reduced in the ESCs transfected with the shRNA targeting Dies1 (Fig. 1D). These results suggest that the suppression of Dies1 hampers ESC differentiation.

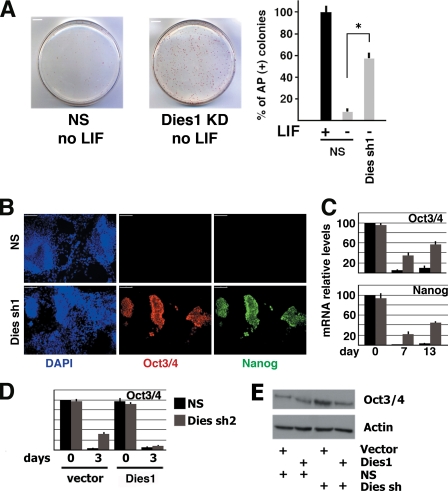

To explore this possibility, we analyzed the expression of alkaline phosphatase (AP), a marker of undifferentiated state, in ESCs grown for 6 days without LIF. Fig. 2 A shows that, as expected, LIF withdrawal abolished the formation of alkaline phosphatase-positive colonies in cells transfected with NS shRNA. In contrast, Dies1 KD cells formed a significant number of colonies positive for AP staining when grown in the absence of LIF. To evaluate the differentiation potential of Dies1 KD ESCs, we injected these cells subcutaneously into the left side of four nude mice. Control ESCs, transfected with nonsilencing shRNA, were injected into the right side of the same mice. Four weeks after the injection, the size of teratomas derived from Dies1 KD cells is four to five times smaller than that of control tumors (see supplemental Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

Dies1 suppression maintains ESCs in undifferentiated state in the absence of LIF. A, ESCs stably transfected with NS or Dies1 silencing shRNAs were grown for 6 days in the absence of LIF and then stained for AP. This marker of ESC undifferentiated state was clearly observed in more than 50% of the colonies of Dies1 KD cells, although only about 10% of the NS shRNA transfected colonies were AP-positive. The experiments were done in triplicate. *, p ≤ 0.001. B, Dies1 KD ESCs grown 13 days in neural differentiation medium still expressed Oct3/4 and Nanog, although NS-transfected cells are completely negative for these master genes of stemness. Scale bars, 250 μm. C, mRNA levels of Oct3/4 and Nanog were measured in cells cultured as in A. The two mRNAs were strongly reduced in NS shRNA-transfected cells (black bars), although they were clearly detectable at 7 and 13 days after the induction of differentiation in Dies1 KD cells (gray bars). D, expression of a Dies1 cDNA resistant to the shRNA used to silence endogenous Dies1 rescued the phenotype of Dies1 KD ESCs. In cells expressing recombinant Dies1 (gray bars), Oct3/4 mRNA was expressed at the same levels of controls (black bars). E, as in D, Oct3/4 protein levels are rescued by Dies1 overexpression.

This block in ESC differentiation was further demonstrated by the observation that Dies1 KD cells grown for 13 day in differentiation medium formed many clusters of cells still expressing markers of the undifferentiated phenotype, such as Oct3/4 and Nanog, whereas their expression was undetectable in ESCs transfected with NS shRNA (Fig. 2B). The persistence of Oct3/4 and Nanog expression in many cell clusters was confirmed by measuring the cognate mRNA levels at various times before and after the induction of differentiation (Fig. 2C). Although Oct3/4 and Nanog mRNAs were suppressed in differentiating cells stably transfected with control NS shRNA, in Dies1 KD cells their expression continued 7 days after the induction of differentiation. After 13 days, Oct3/4 and Nanog mRNAs increased further, suggesting that the fraction of undifferentiated cells expressing these markers was still proliferating. Similar results were obtained in Dies1 KD cells induced to differentiate with the hanging drop method for 8 days (see supplemental Fig. 3). To address the question of whether Dies1 suppression is the cause of the phenomenon we observed, we transfected ESC clones, stably expressing the Dies1-targeting shRNA (Dies sh2), with an expression vector for Dies1 not containing the sequence targeted by the shRNA and thus resistant to silencing. As shown in Fig. 2, D and E, Dies1 overexpression had no significant effects on control ESCs, although it completely rescued the phenotype observed in Dies1 KD cells, as demonstrated by the analysis of Oct3/4 mRNA and protein levels, which became indistinguishable from those observed in control cells.

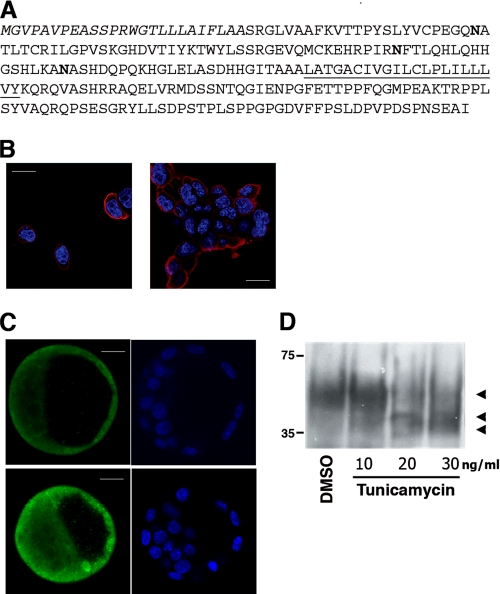

Dies1 Gene Encodes a Type I Membrane Protein

Analysis of the Dies1 gene sequence indicated that it is highly conserved in various species of vertebrates (see supplemental Fig. 4). Predicted amino acid sequence provided evidence that Dies1 could be a transmembrane protein (Fig. 3A). In fact, it possesses a hydrophobic helix with the characteristics of a transmembrane tract. The N-terminal region contains a putative signal peptide and a V-type Ig-like domain, present in the extracellular domain of many membrane proteins (21). To explore this possible transmembrane topology, FLAG-tagged Dies1 cDNA was stably transfected in ESCs. Immunostaining with a FLAG antibody demonstrated that most of the protein is present on the plasma membrane, with some signals on intracellular organelles (Fig. 3B). The same localization was observed when Dies1 was transfected in other cell lines (see supplemental Fig. 5). In addition, the staining of mouse blastocysts with Dies1 antibody confirmed that Dies1 is expressed on the surface of the cells (Fig. 3C).

FIGURE 3.

Dies1 is a membrane protein. A, Dies1 amino acid sequence predicted from mouse Dies1 gene. N-terminal signal peptide is in italic. Three possible Asn glycosylation sites are in boldface. Putative transmembrane tract is underlined. B, confocal images demonstrating that Dies1-FLAG is localized at the plasma membrane of ESCs, in isolated cells (left panels), and in clusters (right panel). Scale bars, 50 μm. C, confocal images of mouse blastocysts stained with Dies1 antibody, which indicate that Dies1 is mainly located on the cell surface. Scale bars, 20 μm. D, Western blot analysis of Dies1-FLAG from ESCs treated with the indicated different concentrations of tunicamycin to inhibit N-glycosylation. The control lane refers to cells treated with DMSO.

Type I transmembrane topology was also supported by the presence of three possible Asn-glycosylation sites in the putative extracellular/intraluminal N-terminal region. The glycosylation of Dies1 was addressed by treating Dies1-FLAG-transfected cells with various concentrations of tunicamycin. As shown in Fig. 3D, inhibition of glycosylation resulted in a significant change of Dies1 migration, thus supporting its N-linked glycosylation.

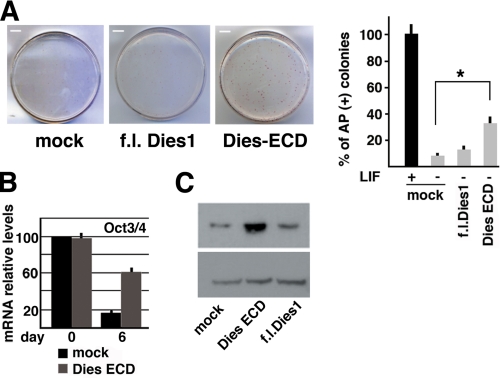

Dies1 Extracellular Domain Exerts Dominant Negative Effects Mimicking Dies1 Silencing

Being localized on the cell surface, we speculated that Dies1 could have receptor functions. To test this possibility, we transfected ESCs with a vector driving the expression of a deletion mutant of Dies1 encoding the entire N-terminal part of the protein, which includes the putative signal peptide and Ig-like domain (Dies-ECD). This protein was found in the conditioned medium (see supplemental Fig. 6), thus confirming the proposed topology of the protein. We postulated that Dies1-ECD was mimicking structural and functional characteristics of the full-length protein, and thus it could work as a dominant negative mutant by competing with the endogenous full-length protein for binding to putative ligands. To test this hypothesis, we cultured ESCs for 6 days without LIF and measured the number of AP-positive colonies. LIF withdrawal from the culture medium led to an almost complete disappearance of AP colonies, indicating that these cells are losing their undifferentiated phenotype (Fig. 4A). Overexpression of full-length Dies1 had no effect, whereas overexpression of Dies1-ECD significantly modified the number of AP-positive colonies, from less than 10% in mock or full-length Dies1-transfected cells to almost 40%. Accordingly, ESCs, stably expressing Dies1-ECD and induced to differentiate by culturing them without LIF, showed a very robust expression of Oct4 mRNA and protein 6 days after the induction of differentiation (see Fig. 4, B and C). Taken together, these results demonstrated that Dies1-ECD is a dominant negative mutant, whose expression results in the same phenotype caused by the suppression of Dies1 and suggested that Dies1 could be involved in signal transduction.

FIGURE 4.

Dominant negative effect of Dies1 extracellular domain. A, ESCs stably transfected with full-length (f.l.) Dies1 or with Dies1 extracellular domain (Dies-ECD) were grown for 6 days in the absence of LIF and then stained for AP. 11% of colonies expressing full-length Dies1 are AP-positive, versus 33% of the Dies-ECD-expressing colonies. The experiments were done in triplicate. *, p ≤ 0.01. B, mRNA levels of Oct3/4 were measured in cells transfected as in A with Dies-ECD. Oct3/4 mRNA is clearly detectable at 6 days after LIF withdrawal. C, Oct3/4 protein in cells transfected with full-length (f.l.) Dies1, Dies-ECD, or empty vector (mock) after 6 days without LIF.

Dies1 Suppression Inhibits BMP4 Signaling

The results described above suggested that the possible functional role of Dies1 in ESC pluripotency and/or differentiation was related to its involvement in signaling events. It is well known that many signaling pathways are active in ESCs grown in the presence of LIF and serum. However, LIF and BMP4 pathways are sufficient to maintain mouse ESCs in serum-free culture (8). Therefore, we explored the possible involvement of Dies1 in these two signaling pathways. As shown in Fig. 5 A, Dies1 knockdown in undifferentiated ESCs did not affect the expression of Oct4, Nanog, Sox2, and Rex1, as well as Stat3, and of other transcription factors involved in the maintenance of the ESC undifferentiated state. Therefore, the involvement of Dies1 in the LIF signaling pathway seems to be unlikely.

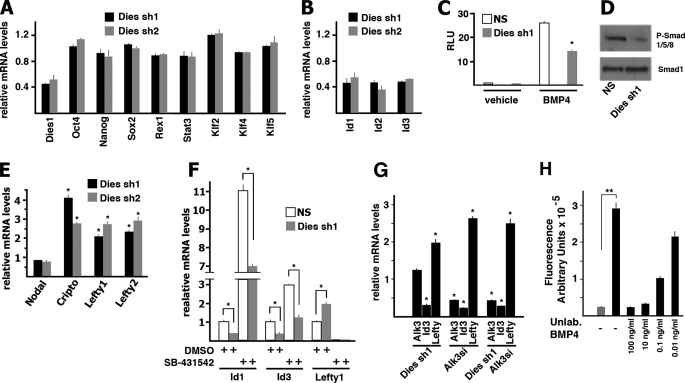

FIGURE 5.

Dies1 suppression inhibits BMP4 signaling pathway. A, mRNA levels of the indicated genes were measured on total RNA by real time PCR. Dies1 KD was obtained with two different shRNAs (Dies sh1 and Dies sh2). B, mRNA levels of genes downstream of the BMP4 signaling pathway. All the Id mRNAs are significantly reduced in Dies1 KD cells compared with nonsilenced cells. All values are significantly (p < 0.01) different from the mean values in NS-transfected cells. C, ESCs stably transfected with NS or Dies1 silencing shRNAs were treated or not with BMP4 and transiently transfected with a vector where the luciferase gene was under the control of the Id1 gene promoter. The values are expressed as fold changes of luciferase/Renilla activity. D, Western blot analysis of ESCs transfected with NS or Dies1 silencing shRNA. The antibodies used recognize Smad1 and the phosphorylated forms of Smads 1/5/8. E, mRNA levels of genes downstream of the Nodal/Activin signaling pathway. F, ESCs stably transfected with NS or Dies1 silencing shRNAs were treated with SB-431542 that inhibits the Nodal/Activin signaling and with DMSO as a control. Id1, Id3, and Lefty1 mRNAs were measured by real time PCR. G, ESCs were transiently transfected with Dies1 shRNAs or Alk3 small interfering RNA or both. Alk3, Id3, and Lefty1 mRNAs were measured by real time PCR. H, BMP4 binds to Dies1 extracellular domain. Europium-labeled BMP4 was incubated with Strep-tagged Dies1 extracellular domain. Unlabeled BMP4 was mixed with the labeled compound at the indicated concentrations. Gray bar represents the fluorescence value measured when labeled BMP4 was incubated in wells not coated with Dies1 ECD (incubated with control conditioned medium of HEK293). Black bars refer to fluorescence of wells coated with Strep-tagged Dies1 ECD. All the experiments were done at least in triplicate. *, p ≤ 0.01; **, p ≤ 0.001.

On the contrary, Dies1 silencing in undifferentiated ESCs resulted in significant decrease of Id1, -2, and -3 mRNAs (Fig. 5B). This decrease was due to a reduced gene transcription, as luciferase expression under the control of the Id1 gene promoter was activated by BMP4 treatment, but this activation was significantly reduced in the presence of Dies1 silencing (Fig. 5C). In agreement with this result, we found that phospho-Smad1/5/8 levels were clearly decreased in Dies1 KD cells (Fig. 5D).

There is a tight cross-talk between the BMP4 and Nodal/Activin pathway. For example, the availability of Smad4, the cofactor used in both pathways, has a significant effect on both pathways (22). Thus, the down-regulation of the BMP4 pathway observed in Dies1 KD cells is expected to induce an up-regulation of the Nodal/Activin pathway due to the increased availability of Smad4. Fig. 5E shows that, as expected, targets of the Nodal/Activin pathway, such as Cripto, Lefty1, and -2, were increased in ESCs where Dies1 was suppressed.

Although the decreased phosphorylation of Smad1 indicated a specific down-regulation of the BMP4 pathway, we cannot exclude that the decreased expression of Id genes we observed in Dies1 KD ESCs could also be a consequence of the activation of the Nodal/Activin pathway. To address this point we inhibited the Nodal/Activin pathway and looked at the effects of Dies1 suppression; Fig. 5F shows that as expected SB-431542, the inhibitor of Nodal/Activin receptors, completely turned off the transcription of the Nodal/Activin targets, such as Lefty1, and this was accompanied by a dramatic increase of Id1 gene expression. Despite the strong increase of Id1 expression, Dies1 suppression still decreased the expression of Id genes, indicating that it was likely to act directly on the BMP4-Smad1/5/8 pathway. On the other hand, when we suppressed BMP4 signaling by the knockdown of its receptor Alk3, we observed, as expected, the down-regulation of Id1 gene and the activation of Lefty1 (see Fig. 5G). In these conditions, Dies1 KD had no effects on Id1 or Lefty1 gene expression thus indicating that Dies1 function is dependent on the BMP4-Alk3 signaling pathway.

To explore the hypothesis of a possible direct interaction between Dies1 and BMP4, we designed an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay approach. Strep-tagged Dies1 ECD secreted by HEK293 cells was bound to 96-well plates coated with anti-tag antibody. The plates were then incubated with BMP4 labeled with Europium. Fig. 5H shows that labeled BMP4 interacts with Dies1-coated wells, thus supporting the hypothesis of a direct interaction of the extracellular domain of Dies1 with Bmp4.

Block of ESC Differentiation Induced by Dies1 Silencing Is Due to the Activation of Nodal/Activin Pathway

It was clearly demonstrated that Id proteins, whose expression is induced by BMP4, suppress ESC differentiation (8). Therefore, the observations that Dies1 KD prevents differentiation and at the same time it down-regulates Id proteins were apparently conflicting. Although the effects of Id constitutive expression in ESCs was studied in detail (8), no data are available, at least to our knowledge, on the effects of the suppression of Id proteins. In our experimental conditions, suppression of Id genes, down to ∼40% of normal levels, showed no significant morphological changes and were maintained in culture for at least 2 weeks with no difference compared with control cells. This phenotype was confirmed by the observation that Oct4 and Nanog did not vary upon the KD of Id1 (see supplemental Fig. 7).

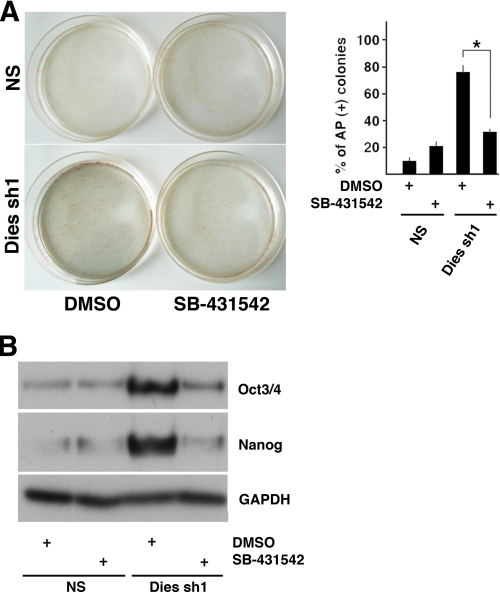

Another possible explanation of the phenotype observed in Dies1 KD cells is the activation of the Nodal/Activin pathway as a consequence of the inhibition of the BMP4 signaling. To address this point, we studied the phenotype of ESCs where Dies1 was suppressed and the Nodal/Activin pathway was inhibited by SB-431542. As shown in Fig. 6, the number of AP-positive colonies still present when the cells were grown 6 days in the absence of LIF was significantly decreased in Dies1 KD cells treated with the inhibitor compared with the cells where the Nodal/Activin pathway was not inhibited. Accordingly, in the same experimental conditions, the levels of Oct3/4 and Nanog were significantly reduced in SB-431542-treated cells. These results indicated that at least part of the effect of Dies1 silencing on ESCs is due to the up-regulation of the Nodal/Activin pathway.

FIGURE 6.

Inhibition of Nodal/Activin signaling pathway masks the effects of Dies1 silencing in ESCs. A, ESCs stably transfected with NS or Dies1 silencing shRNAs were grown for 6 days in the absence of LIF and then stained for AP. Cells were treated with SB-431542 or with DMSO as a control. % of colonies AP-positive was calculated in triplicate experiments. *, p ≤ 0.001. B, Western blot analysis of Oct3/4 and Nanog in the cells treated as described in A.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we characterized a new protein that was named Dies1. We demonstrated that it is necessary for proper differentiation of ESCs. This observation let us to uncover the involvement of Dies1 in the BMP4 signal transduction machinery.

Dies1 was identified through the screening of a large collection of shRNAs targeting mouse mRNAs (23). The silencing of Dies1 induced an evident block of ESC differentiation either toward neurons or cardiomyocytes. Dies1 KD cells, unable to differentiate, maintained the expression of stem cell undifferentiated markers, like Oct3/4, Nanog, and AP. The obvious conclusion was that Dies1 KD was altering the ESC molecular phenotype, thus rendering them no longer dependent on extracellular signals to maintain the undifferentiated phenotype. One possible explanation of this phenomenon is that Dies1 suppression was influencing the function and/or the expression of effector genes downstream from the signaling pathway active in mESCs. We first looked at the targets of the LIF pathway, which was completely unaffected by Dies1 KD. On the contrary, the downstream targets of Nodal/Activin and BMP4 signaling cascades were significantly altered, with the first one activated, whereas BMP4 targets were inhibited. BMPs represent a family of growth factors, which control numerous biological functions, such as bone formation, differentiation of various tissues, and also proliferation and migration (24). In addition to these well described roles, BMP4 has crucial functions in ESCs. The effects of BMP4 were apparently due to two main mechanisms. (i) It sustains the transcription of Id genes, in particular Id1 and Id3, which are known to prevent differentiation (8). (ii) It contributes to maintaining ESCs in the undifferentiated state that is based on the inhibition of the MAPK pathway (13). Our results confirm that the BMP4 signaling pathway is active in mESCs and indicate that regulation of this pathway is still not completely understood.

The molecular mechanisms through which Dies1 affects BMP4 signaling are not clear. When we identified Dies1, it was an unannotated mouse cDNA sequence. In silico analysis indicated the possibility that it encoded a single pass transmembrane protein, which contained, in the putative extracellular region, a V-type Ig-like domain. The hypothesis that Dies1 is a membrane protein is supported by two main findings (i) Immunostaining experiments clearly demonstrated that FLAG-tagged Dies1 was localized at the plasma membrane. (ii) N-Linked glycosylation sites present in the Dies1 sequence are indeed glycosylated. Therefore, Dies1 can be considered a bona fide plasma membrane protein. The immunoglobulin fold is a domain present in hundreds of proteins, with a wide spectrum of functions (21). Therefore, the presence of such a domain in Dies1 did not help to understand its function. On the other hand, the transmembrane region and the intracellular domain of Dies1 are evolutionarily very conserved. The transmembrane tract is similar to that of other single pass membrane proteins such as cadherin6 and NCAM-1, although we did not find any significant homology with the cytosolic domain of other proteins. The Dies1 cytodomain contains numerous possible Ser, Thr, and Tyr phosphorylation sites, and we also observed that immunoprecipitated Dies1 is detected by an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody and vice versa, thus suggesting its phosphorylation on tyrosine residues. On this basis, one possibility is that Dies1 functions as a BMP4 co-receptor, modulating the activity of BMP4 signaling machinery. According to this hypothesis, we observed that the expression of a deletion mutant of Dies1, containing only the putative extracellular domain of the protein, had a strong dominant negative effect, similar to that observed in the cells KD for Dies1. This observation suggests that this domain was interfering, probably in the intraluminal space of the secretory pathway, with the assembly of a complex, including Dies1, and was crucial for the BMP4 signaling, perhaps including the BMP4 receptor. According to this possibility, we observed that the extracellular domain of Dies1 and BMP4 directly interact, at least in vitro. Some other possible mechanisms could be probably excluded, like those implying Dies1 involvement in signaling events converging on the BMP4 pathway downstream of its receptor. In fact, we observed that Alk3 suppression completely blocks the effects of Dies1 KD.

Another important issue that deserves to be discussed is that of the effects of Dies1 suppression on the Nodal/Activin signaling pathway. It was previously demonstrated that this signaling pathway has an important role in ESC. In human ESCs, downstream targets of the Nodal signaling pathway, such as Lefty2, are enriched, and the phosphorylation and nuclear localization of Smad2–3, the Smads of the Nodal pathway, suggested that Nodal plays a role in the maintenance of human ESC pluripotency (25). In mESCs, it was clearly demonstrated that Nodal/Activin signaling has an important role in mESCs proliferation (16). In our experimental conditions, we have observed that up-regulation of this pathway is crucial for the block of ESC differentiation induced by Dies1 KD, because the inhibition of the Nodal/Activin receptor actually erases the effects of Dies1 KD. Therefore, our results support the possibility that Nodal/Activin signaling controls mESC propagation, but when up-regulated, it is also able to support ESC self-renewal in the absence of LIF. In conclusion, at least in our conditions, mESC self-renewal and propagation seem to depend on the equilibrium between the Nodal/Activin and BMP4 signals. The existence of a cross-talk between these two pathways is suggested by several results. It is well known that the two main signaling cascades of the TGFβ superfamily, one based on Smad2/3 (Nodal/Activin) and the other on Smad1/5/8 (BMP), share the co-factor Smad4. Thus, when both pathways are active in a given cell, blocking one of them inevitably results in the up-regulation of the other one because of the increased availability of Smad4 (22). Therefore, the suppression of BMP4 signaling due to knockdown of Dies1 results in the up-regulation of the Nodal/Activin pathway, which is not compatible with the differentiation program induced by LIF withdrawal.

In conclusion, Dies1 is a necessary factor of BMP4 signaling and has an evident role in mESCs. Moreover, the expression profile of Dies1, inferred from EST sources, indicates that the adult tissue expressing the highest level of Dies1 is the bone, where BMP4 is present at the highest levels. This indication suggests that Dies1 could also be required and could regulate BMP4 in adult cells, as well as in mESCs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

Acknowledgment—We thank Caterina Missero for reading the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from EC-Sirocco Consortium, Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro, and Italian Ministry of Health.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–7 and Table 1.

- ESC

- embryonic stem cell

- LIF

- leukemia inhibitory factor

- TGFβ

- transforming growth factor β

- BMP

- Bone morphogenetic protein

- ECD

- extracellular domain

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- AP

- alkaline phosphatase

- shRNA

- small hairpin RNA

- NS

- nonsilencing

- KD

- knockdown

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- m

- murine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boiani M., Schöler H. R. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 872–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niwa H. (2007) Development 134, 635–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loh Y. H., Wu Q., Chew J. L., Vega V. B., Zhang W., Chen X., Bourque G., George J., Leong B., Liu J., Wong K. Y., Sung K. W., Lee C. W., Zhao X. D., Chiu K. P., Lipovich L., Kuznetsov V. A., Robson P., Stanton L. W., Wei C. L., Ruan Y., Lim B., Ng H. H. (2006) Nat. Genet. 38, 431–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers I., Tomlinson S. R. (2009) Development 136, 2311–2322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith A. G., Heath J. K., Donaldson D. D., Wong G. G., Moreau J., Stahl M., Rogers D. (1988) Nature 336, 688–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niwa H., Burdon T., Chambers I., Smith A. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 2048–2060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuda T., Nakamura T., Nakao K., Arai T., Katsuki M., Heike T., Yokota T. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 4261–4269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ying Q. L., Nichols J., Chambers I., Smith A. (2003) Cell 115, 281–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massagué J., Blain S. W., Lo R. S. (2000) Cell 103, 295–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watabe T., Miyazono K. (2009) Cell Res. 19, 103–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmierer B., Hill C. S. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 970–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Balemans W., Van Hul W. (2002) Dev. Biol. 250, 231–250 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi X., Li T. G., Hao J., Hu J., Wang J., Simmons H., Miura S., Mishina Y., Zhao G. Q. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6027–6032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ying Q. L., Wray J., Nichols J., Batlle-Morera L., Doble B., Woodgett J., Cohen P., Smith A. (2008) Nature 453, 519–523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee M. Y., Lim H. W., Lee S. H., Han H. J. (2009) Stem Cells 27, 1858–1868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogawa K., Saito A., Matsui H., Suzuki H., Ohtsuka S., Shimosato D., Morishita Y., Watabe T., Niwa H., Miyazono K. (2007) J. Cell Sci. 120, 55–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vallier L., Mendjan S., Brown S., Chng Z., Teo A., Smithers L. E., Trotter M. W., Cho C. H., Martinez A., Rugg-Gunn P., Brons G., Pedersen R. A. (2009) Development 136, 1339–1349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soncin F., Mohamet L., Eckardt D., Ritson S., Eastham A. M., Bobola N., Russell A., Davies S., Kemler R., Merry C. L., Ward C. M. (2009) Stem Cells 27, 2069–2080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parisi S., Passaro F., Aloia L., Manabe I., Nagai R., Pastore L., Russo T. (2008) J. Cell Sci. 121, 2629–2634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maltsev V. A., Rohwedel J., Hescheler J., Wobus A. M. (1993) Mech. Dev. 44, 41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aricescu A. R., Jones E. Y. (2007) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 543–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyazono K., Kusanagi K., Inoue H. (2001) J. Cell Physiol. 187, 265–276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva J. M., Li M. Z., Chang K., Ge W., Golding M. C., Rickles R. J., Siolas D., Hu G., Paddison P. J., Schlabach M. R., Sheth N., Bradshaw J., Burchard J., Kulkarni A., Cavet G., Sachidanandam R., McCombie W. R., Cleary M. A., Elledge S. J., Hannon G. J. (2005) Nat. Genet. 37, 1281–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hogan B. L. (1996) Genes Dev. 10, 1580–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.James D., Levine A. J., Besser D., Hemmati-Brivanlou A. (2005) Development 132, 1273–1282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niwa H., Miyazaki J., Smith A. G. (2000) Nat. Genet. 24, 372–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.