Abstract

Objective

We sought to assess the appearance of cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) on magnetic resonance (MR) imaging in murine Ccm1 and Ccm2 gene knockout models, and to develop a technique of lesion localization for correlative pathobiologic studies

Methods

Brains from eighteen CCM mutant mice (Ccm1+/-Trp53-/- and Ccm2+/-Trp53-/-) and 28 controls were imaged by gradient recalled echo (T2*)-weighted MR at 4.7 T and 14.1 T in vivo and/or ex vivo. After MR imaging, the brains were removed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin and cells were laser microdissected for molecular biologic studies.

Results

T2*-weighted MR imaging of brains in vivo and ex vivo revealed lesions similar to human CCMs in mutant mice, but not in control animals. Stereotactic localization and hematoxylin and eosin-staining of correlative tissue sections confirmed lesion histology, and revealed other areas of dilated capillaries in the same brains. Some lesions were identified by MR imaging at 14.1 T, but not at 4.7 T. PCR amplification from Ccm1 and β-actin genes was demonstrated from nucleic acids extracted from laser microdissected lesional and perilesional cells.

Conclusions

The high field MR imaging techniques offer new opportunities for further investigation of disease pathogenesis in vivo, and the localization, staging and histobiologic dissection of lesions, including the presumed earliest stages of CCM lesion development.

Keywords: imaging, intracranial hemorrhage, MRI, stroke, hemorrhagic, vascular malformations

Introduction

The cerebral cavernous malformation (CCM) is a highly prevalent vascular pathology consisting of clusters of dilated hemorrhagic capillaries, devoid of mature vessel wall elements (22, 23). They occur in sporadic and inherited forms, predisposing patients to a lifetime risk of hemorrhagic stroke and other clinical sequelae (14, 15, 20-22). CCM disease in humans can be effectively diagnosed by magnetic resonance (MR) imaging. Clinical imaging of CCM lesions in human patients has been well characterized at low MR field strengths (18, 19). We have recently presented preliminary data from imaging of human lesions at high field strengths (accompanying manuscript). However, the imaging of human lesions presents inherent limitations of follow-up and sampling for histobiologic studies. It is unlikely that human lesions can be sampled at early stages of development or at multiple sites in the brain of the same patient.

Murine models offer advantages of characterization and follow-up of disease states, histobiologic dissection and experimental manipulation that are impossible to conduct in human patients. With regard to imaging by MR, murine models have additional advantage of allowing in vivo imaging at higher magnetic field strengths than is currently possible in humans and the follow-up and sampling of lesions at various stages of development, even within the same brain.

In order to create animal models for autosomal dominant CCM, the mouse orthologues of the human CCM1 and CCM2 genes were targeted for mutation, using a gene knockout approach for murine Ccm1 and by employing an existing gene-trap insertion ES cell line for murine Ccm2. Animals heterozygous for either of these mutations did not exhibit overt cerebrovascular lesions and those homozygous are embryonic lethal (16, 17). However, cerebrovascular lesions were identified when the Ccm mutations were crossed into a genetic background lacking the tumor suppressor Trp53 gene due to homozygous mutation (Ccm1+/-Trp53-/- and Ccm2+/-Trp53-/-). The lesions in mutant mice exhibited similar histology to that of human CCM lesions, with blood filled caverns lined by a single layer of endothelium, and were identified in 1/3 to 1/2 of the mice (16, 17). However, their detection required serial sectioning of the entire brain followed by histological staining of the full series of sections. The inability to detect these lesions in a high throughput manner and to follow their development in living animals severely limits the use of these otherwise relevant mouse models for the study of CCM pathogenesis.

The objectives of this study were to determine whether MR imaging can be used to more efficiently detect these lesions in vivo and ex vivo and thereby increase the research impact of these murine CCM models. In this report we describe the detection and MR features of CCM lesions in the murine models, and present techniques of lesion localization and pathobiologic sampling.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

Double mutant mice and littermate controls were bred and genotyped at Duke University according to procedures previously published (16, 17). In this study we imaged eighteen animals, including Ccm1+/-Trp53-/- (six males, four females) and Ccm2+/-Trp53-/- mice (six males, two females) and 28 controls, including Ccm2+/-Trp53+/+ (four males, two females), Ccm1+/-Trp53+/+, (nine males, five females), Ccm1+/+Trp53-/- (four males, one female) and three male C57BL6 mice. Mice, shipped to Evanston Northwestern Healthcare (ENH) at one to three months of age, were quarantined for six weeks before MR imaging. Our protocol was approved by the Animal Review Committee of the ENH Research Institute. All animals received humane care in compliance with the Principles of Laboratory Care formulated by the National Society for Medical Research and with the National Institute of Health’s Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the National Academy of Sciences.

MR Imaging Protocols

The Ccm+/-Trp53+/+ controls were imaged in vivo at age 10-19 months. Previous work revealed that these mice do not develop CCM lesions at an earlier age (17). The advanced age was chosen for imaging the brains of these mice to maximize the potential detection of occult CCM lesions by imaging, since more lesions and larger lesions are expected with time. The brains of the other control and all double mutant mice were imaged in vivo by MR at age 3-7 months, because of the tendency of these mice to die from systemic tumors by 6-7 months of age.

Animals were anesthetized for imaging by intraperitoneal injection of Nembutal Sodium solution (Abbott Laboratories Abbott Park, IL) at 70 mg/kg, followed by inhalation of isoflurane (2% in oxygen/air) via nose cone. Eyes were treated with erythromycin ointment (Fougera, Melville, NY) to prevent dryness. Mice were allowed to recover spontaneously from anesthesia upon completion of imaging.

Brains were removed from mice that died naturally or upon planned euthanasia by an overdose of Nembutal after in vivo imaging. Brains were rinsed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to remove excess blood, and were placed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 2-4 weeks before ex vivo MR imaging. Immediately prior to MR imaging, brains were rinsed in PBS and placed securely into 12 mm vials. Fomblin Y LVAC 06/6 perfluoropolyether (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) surrounded each brain sample to prevent dehydration and reduce magnetic susceptibility differences.

MR imaging was conducted in vivo or ex vivo by using a 4.7 Tesla (T) Bruker Biospec (200 MHz) and/or a 14.1 T Bruker Avance (600 MHz) imaging spectrometer, with 25 mm birdcage coils. 3D-gradient recalled echo (GRE) images were acquired in vivo and ex vivo with the 4.7 T spectrometer using TR/TE 100ms/10ms, with slice thickness 250 μm and in-plane pixel size 113 μm. After its installation, studies were shifted to the newer 14.1 T imager, with opportunity to image some animals at both field strengths. 3D-GRE images were acquired in vivo with the 14.1 T spectrometer using TR/TE 25ms/5ms, with slice thickness 125 μm and in-plane pixel size 78 μm. 3D-GRE images of brains were acquired ex vivo with the 14.1 T spectrometer using TR/TE 25ms/7.8ms, with slice thickness 117 μm and in-plane pixel size 27 μm. The duration of in vivo image acquisition at 14.1 T was maintained at no longer than two hours, hence the higher pixel size as compared to ex vivo imaging, where image acquisition of several hours was possible. These differences in imaging techniques were considered carefully when analyzing the results.

Suspected lesions were identified independently by two investigators (RS, J-CZ), and were adjudicated by a third observer (PNV), the latter being an expert in MR imaging without prior experience with CCM disease. Lesions were identified in three planes on in vivo and ex vivo images, and excluded if they appeared to communicate with a brain slit (open trauma) in ex vivo images. Imaging was conducted in both control and mutant animals, and lesion detection was adjudicated (in control and mutant animals) by review of all serial images of the whole respective brains by an MRI investigator (PNV) not familiar with CCM biology, and blinded to animal genotype.

Stereotactic Localization of Lesions and Histological Correlation

Once the suspected CCM lesions were identified and located by MR, the location and maximal diameter of the lesion were plotted on stereotactic grids (Figure 1A and 1B). Lesions were located within 1-mm coronal sections starting with the most caudal section at the cerebellar hindbrain and ending with the olfactory bulbs at the frontal rostrum, and within one of four quadrants in the coronal slice of interest. Brains were removed from the vials, rinsed in PBS, immersed in neutral buffered formalin, cut into 1-mm thick coronal sections corresponding to the grid in Figure 1A and embedded in paraffin. The 1-mm thick sections suspected of containing lesions by MR imaging were sliced at 5 μm with a microtome, and the thin coronal sections were whole mounted either onto charged microscope slides for staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) or onto uncharged slides for cell isolation described below.

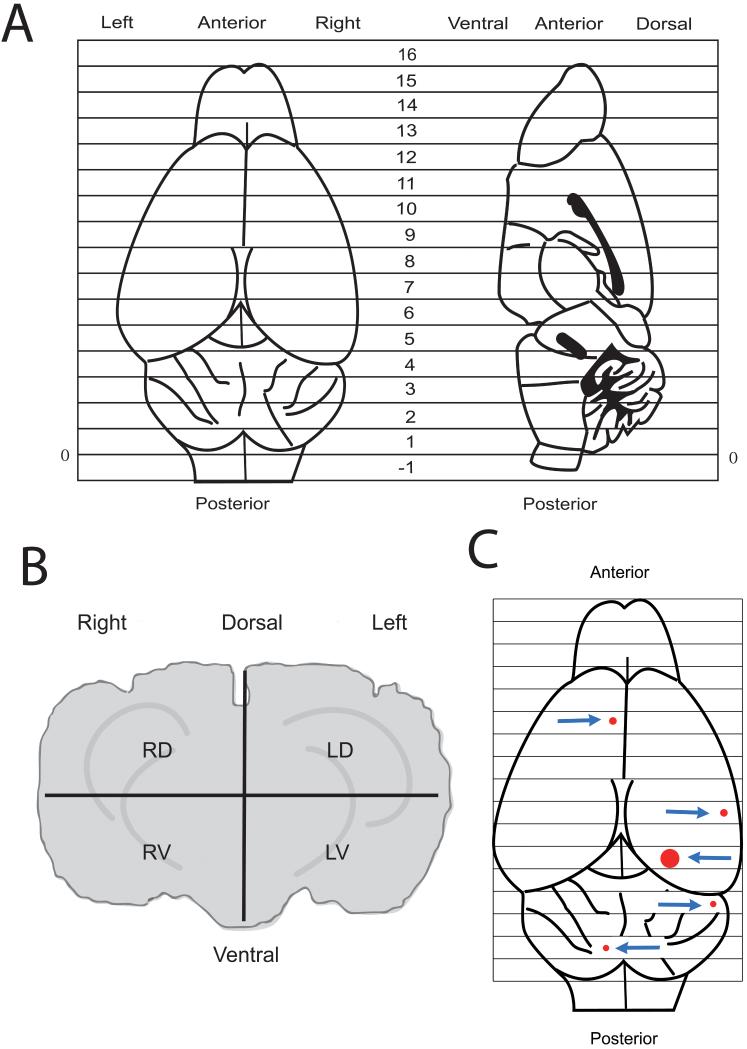

Figure 1.

Stereotactic drawings of views of mouse brain to locate CCM lesions. (A) Top view and midsagittal planes with locations of 1-mm serial anatomic coronal sections from the most caudal section at the cerebellar hindbrain to the olfactory bulbs at the frontal rostrum. (B) A coronal section divided into four quadrants: right dorsal (RD), left dorsal (LD), right ventral (RV) and left ventral (LV). (C) Location (arrows) and relative sizes of five lesions within the brain of a Ccm1+/-Trp53+/+ mouse determined by MR imaging ex vivo at 14.1 T.

Laser Capture Microdissection (LCM) of Mouse Brain Cells

The Arcturus Pixcell IIe LCM System was used for capturing specific cells from fixed and fresh mouse brains. To obtain a frozen specimen, the brain was removed within 30 minutes of death by inhalation of carbon dioxide by first removing the skin and tissue surrounding the skull and then carefully removing small pieces of the skull with surgical scissors starting with the foramen magnum at the base of the skull without disturbing the integrity of the brain. The brain was gently removed in a single piece, rinsed in PBS to remove excess blood and placed in a plastic base mold containing Optimal Temperature Compound. The mold containing the brain was frozen in a dry ice bath containing isopentane and stored at -80°C. The frozen brain was sectioned in the coronal plane. Serial frozen sections were sliced to 5-μm thicknesses with a microtome with a cryostat, placed on uncharged microscope slides (Arcturus) and stained using a HistoGene™ LCM Frozen-Section staining kit (Arcturus). This process included staining with HistoGene™ Staining Solution, and dehydration with graded alcohols before capturing cells with the LCM System onto CapSure™ HS Caps (Arcturus). The same staining kit was used with the paraffin-embedded sections from formalin fixed brain, with additional steps, including removal of paraffin with xylenes before staining, according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

DNA and RNA was isolated from the cells of frozen specimens by placing the laser captured cells (endothelial cells from CCM lesions or control blood vessels or perilesional neuro-glial cells) within the caps and using PicoPure™ DNA and RNA Extraction Kits (Arcturus), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA and DNA isolation was verified from laser captured cells on frozen sections by amplification of cDNA reverse transcribed from RNA and DNA using primers from sequences on two separate exons, spanning an intron, of the β-actin gene (Maxim Biotech, South San Francisco, CA). We initially chose to investigate β-actin as a control for feasibility because this gene has a high copy number of RNA transcripts, before investigating the expression of genes with a lower number of transcripts.

DNA was isolated from LCM endothelial cells from paraffin embedded slides as described above and amplified by PCR for exon 7 of murine Ccm1 (used for feasibility to eventually study somatic mutations) in two rounds of 40 cycles using a BioRad iCycler in a 25 μl total volume containing: 1x Platinum High Fidelity Buffer (Invitrogen), 2 mmol/L magnesium sulfate, 0.08 mmol/L dNTP mix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 50 ng each primer and 1 unit Platinum High Fidelity Taq (Invitrogen). For second round PCR, 2 μl from the first reaction was added to a total 25 μl reaction volume as above. First and second round cycling conditions were: 94°C for 4 minutes; 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 seconds, 55°C for 45 seconds, 72°C for 45 seconds; and a final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes.

First round outer primers included:

5′-CAAATCGGGTAAGTTGAATTTTG-3′ and 5′-CCAGAGGCAGTGCTCAGAC-3′.

Second round inner primers included:

5′-CATCTGAGGCTTTTAAGTAATTTTTAT-3′ and 5′-GGAAAGGCAATAAGAGTAAAACCA-3′.

The PCR products were visualized on a 1% agarose gel with ethidium bromide.

Results

Suspected CCM lesions were present in 83% (5 out of 6) of the Ccm1+/-Trp53-/- and 62% (5 out of 8) of the Ccm2+/-Trp53-/- mutant mice when imaged in vivo by MR (Table 1). These lesions appear as dark spots in GRE images (Figure 2A). H&E staining confirmed the histopathology of CCM lesions (N = 3 lesions, one lesion in each of three brains) as shown in Figure 2B. In contrast, no lesions were found in the brains of 23 control mice similarly imaged in vivo.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of Suspected CCM Lesions in Mice Imaged In Vivo by MR*

| Number of mice imaged | Mice with suspected CCMs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Male | Female | Total | Male | Female | |

| CCM models | ||||||

| Ccm1 +/- Trp53 -/- | 6 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Ccm2 +/- Trp53 -/- | 8 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Controls | ||||||

| Ccm2 +/- Trp53 +/+ | 6 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ccm1 +/- Trp53 +/+ | 13 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ccm1 +/+ Trp53 -/- | 4 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Six double mutant mice and all 23 controls were imaged only at 4.7 T; others only at 14.1 T.

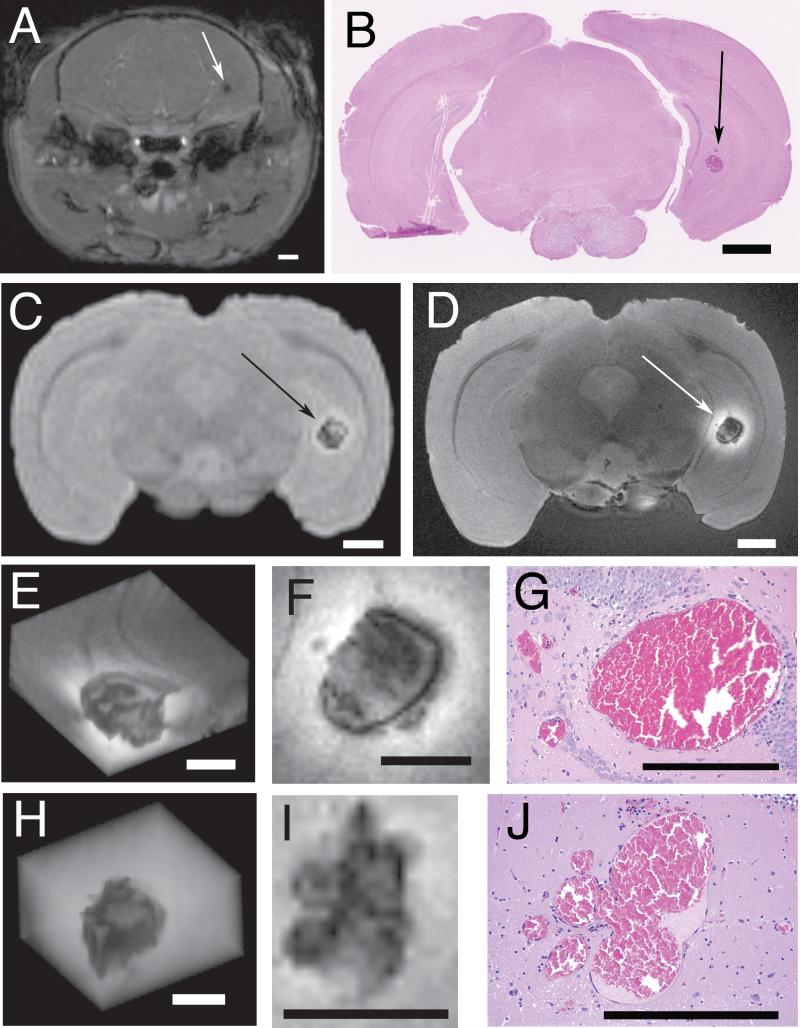

Figure 2.

CCM lesions within brains of two Ccm1+/-Trp53+/+ mice. Three dimensional gradient recalled echo MR imaging of a mouse brain in vivo at 4.7 T (A) and ex vivo at 4.7 T (C) and at 14.1 T (D). The section was stained with H&E (B). The CCM is indicated by arrows (A-D). Enlarged images of the lesion from this mouse (E-G) and from another mouse (H-J) include 3D reconstructions (E, H) and single slice (F, I) from gradient recalled echo MR acquired at 14.1 T field strength and corresponding histologic sections stained with H&E (G, J). Scale bars are 1 mm (A-D) and 0.5 mm (E-J).

In Vivo versus Ex Vivo Imaging

All lesions found in the in vivo images (N = 3 lesions, one lesion in each of three brains) were also seen in the ex vivo images at the same field strength (Figure 2A and 2C). Lesions were present in the brains of all eight Ccm1+/-Trp53-/- mice imaged ex vivo (N = 1, 1, 3, 3, 5, 12, 14, 36 lesions/brain). In comparison, no lesions were found in any of the eight control brains that were removed from three Ccm1+/-Trp53+/+, two Ccm1+/+Trp53-/- and three C57BL6 mice, and imaged ex vivo using same MR technique.

High Field versus Low Field Imaging

The brains from three Ccm1+/-Trp53-/- mice were imaged ex vivo by MR both at 4.7 T and 14.1 T. High field (14.1 T) imaging revealed more detail in lesions than low field (4.7 T) imaging (Figure 2D, 2E, 2F, 2H and 2I). In the core of one CCM lesion (Figure 2F), there appeared several dark foci interspersed in heterogeneous gray intensity. The core is circumscribed by a thin dark rim which is surrounded by a diffuse, bright outer rim. Smaller dark lesions appear to be budding from the thin dark rim. In the core of the other CCM lesion (Figure 2I), there were also several dark foci interspersed in heterogeneous gray intensity, but this lesion lacked the dark rim seen in the first CCM lesion. The dark spots and dark rim are most likely from iron in hemosiderin and other blood breakdown products (4). The enhanced signal intensity of the bright outer rim indicates the presence of iron as methemoglobin, a T1-shortening compound, in that region (4). Regions of intermediate signal intensity may represent varying levels of iron in different oxidation states (4). The distribution and relative sizes of five lesions in the brain of a transgenic mouse revealed by MR imaging at 14.1 T is shown in Figure 1C.

Assessment of Potential False Positives

Two lesions detected by MR imaging in Ccm1+/-Trp53-/- and Ccm2+/-Trp53-/- mice proved to be tumors upon histologic analysis (not shown). The tumors appeared glial in origin, and highly malignant, with occasional hemorrhages, but without any hint of abnormal dilated CCM-like vasculature in the tumor proper. Similar tumors have been found by other investigators in the brains of p53-/- mice (8, 10). The two brains each contained other smaller typical CCM lesions (N = 1 lesion/brain) in regions distinct from the tumor that were also visualized by MR imaging.

Some suspected lesions (N = 5, 14 lesions/brain) in two brains on ex vivo MRI at 4.7 T were later identified as open trauma, when imaged at 14.1 T (not shown) using higher spatial resolution and applying the criteria stated in the Materials and Methods section for lesion identification. This trauma, not seen in any in vivo image, was presumably caused by brain removal.

Lesion Histopathology

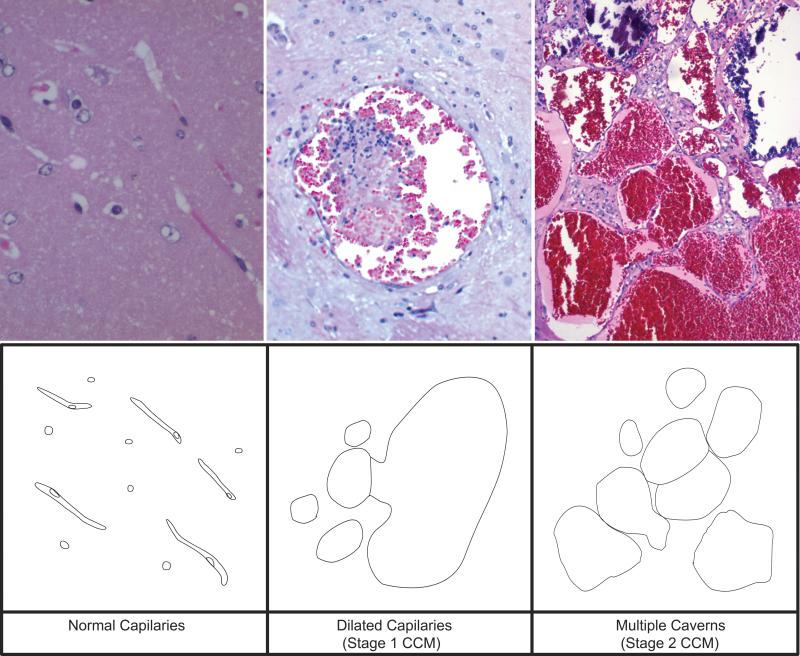

After MR imaging, sections from three Ccm1+/-Trp53-/- and one Ccm2+/-Trp53-/- mouse brains were stained with H&E. Figure 2 illustrates two such cases, where stained coronal sections of Ccm1+/-Trp53-/- mouse brains reveal the presence of CCM lesions (consisting of blood filled dilated caverns, surrounded by a single layer of endothelial cells. There are smaller lesions near the larger lesion, and apparent budding of smaller cavern form a larger one. Another CCM was confirmed by H&E for a suspected lesion within the brain a Ccm2+/-Trp53-/- mouse (Figure 3 upper center). No true CCM lesions were detected on histology that was missed on MRI. Elsewhere in the brains of these same animals, there were areas of dilated capillaries indicating potential pre-lesional sites, many unsuspected on MR (not shown).

Figure 3.

Staging of lesions. H&E stained sections from the brain of a Ccm1+/-Trp53-/- mouse (top) and artist description (bottom) showing normal capillaries (left), Stage 1 CCM lesion (center) and Stage 2 CCM lesion (right). The top right panel is from Reference (16).

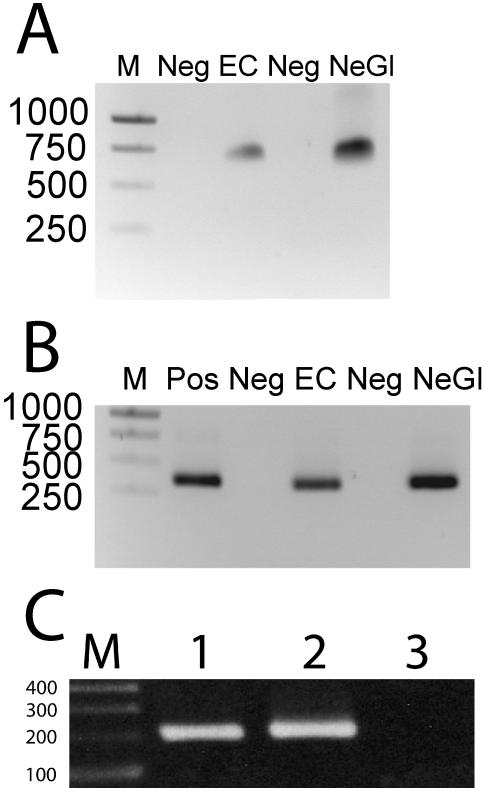

Verification of Nucleic Acids Isolated from Lesion and LCM Control Cells

DNA and RNA isolation from laser captured endothelial and perilesional neural-glial cells from frozen mouse brain was verified by the observation of a 700-bp PCR product generated by amplification of the isolated DNA (Figure 4A) or a 349-bp PCR product generated by amplification of cDNA reverse transcribed from isolated RNA (Figure 4B) with β-actin primers, verifying that the larger product from genomic DNA contained an intron not present in the spliced RNA transcript. DNA isolation from laser captured endothelium from a CCM lesion and normal vessels from a formalin-fixed paraffin embedded Ccm1+/-Trp53-/- mouse brain was verified by PCR products generated by amplification of Ccm1 exon 7 (Figure 4C)

Figure 4.

DNA and RNA from murine brains. Electrophoresis of β-actin gene products amplified from (A) DNA and (B) cDNA reverse transcribed RNA from endothelial (EC) and perivascular neuroglial (Ne-Gl) cells isolated by LCM from the brain of a wild type mouse. Agarose gels were run with DNA size markers (M) indicated by number of basepairs, negative control (Neg) and positive control DNA (Pos). (C) PCR amplification of DNA from LCM endothelial cells from Ccm1+/-Trp53-/- mouse brain. Amplification of Ccm1 exon 7 results in a 200 bp product. 1) DNA isolated from CCM lesion endothelial cells. 2) DNA from endothelial cells from a normal brain region. 3) No DNA control.

Discussion

We provide the first observations of CCM lesions in Ccm mutant mice, imaged at lower and higher MR fields. The CCMs have been successfully identified, localized, and confirmed histologically in the only known animal model of this disease, and lesional and control cells have been successfully captured for ongoing molecular biologic studies.

Given the small size of many lesions and their undercounting by unguided histopathologic exploration, we identified lesions in higher fraction of cases than had been reported in gross histopathologic surveys of the same models (16, 17). Mouse CCM lesions, as small as 0.2 mm in diameter, could be detected on MR in vivo. Ex vivo imaging at 14.1 T produced higher resolution images of the same lesions, and revealed a greater number of smaller lesions than observed by in vivo imaging. This was likely due to the shorter MR imaging periods required by anesthesia time and the pulsations of breathing and blood flow in living animals. The additional smaller lesions revealed by ex vivo imaging of double mutant, but not control mice, are presumed early stages of lesion genesis, such as dilated capillaries. On histology, these are vascular lumens lined by a single layer of endothelium, and lacking mature vessel wall elements. These are easy to distinguish from normal capillaries by the lumen diameter, accommodating many red blood cells, while normal capillaries barely accommodate one or two red blood cells.

The ex vivo imaging introduces potential traumatic artifacts, and these are expectedly easier to distinguish with greater resolution in high field than low field images. It is not known if these artifacts would be lessened by intravascular perfusion fixation prior to brain removal, although such perfusion fixation could also introduce artifactual changes in very brittle endothelial layer of pathologic vessels. Because of brain removal artifacts and potential tumor false positives, histopathologic examination remains essential for absolute confirmation of CCM lesions before using tissue from these transgenic mice for pathobiologic studies.

We chose GRE sequences imaging for these experiments based on CCM biology (i.e. hemosiderin) (4, 7, 13) and our own work on human CCMs (accompanying manuscript), to maximize sensitivity of lesion detection despite potential higher magnetic susceptibility. Conversely, it is anticipated that the angioarchitecture of larger lesions would be better studied using proton density imaging (accompanying manuscript), less susceptible to magnetic blossoming. Despite GRE sequences, there were dilated capillaries in the brains of mutant animals that were not detectable by MR, even upon retrospective review. As expected, imaging at 14.1 T revealed more details of the architecture of the mouse CCM as a result of higher spatial resolution and greater sensitivity to iron levels and oxidation states. The imaging studies described in the present work are preliminary for gross method optimization of image detection, and do not address quantitative hypotheses. It is possible that other imaging sequences and enhancement by intravenous paramagnetic contrast agents can better delineate lesions from artifacts and tumors. Such image acquisition optimization, for sensitivity and spatial resolution, will be addressed in future studies.

Animals started dying at six months of age, typically from systemic tumors related to the p53-/- background. In order to avoid the p53-/- background, more specific modeling based on conditional gene knockout are being pursued, but have not been successful to date. Other models of phenotypic sensitization than p53-/- background may be used, including irradiation of Ccm+/- animals, to generate lesions that can be followed over longer time span.

Using stereotactic coordinates, we have had no difficulty localizing lesions as small as 0.2 mm in diameter, representing large capillaries, and exhibiting minor foci of hemorrhage, but lacking multicavernous features of the disease, gliosis, and other reactive changes. These early lesion stages will need to be studied for early prevalence of somatic mutations (9), cell proliferation (24), ultrastructural defects in blood brain barrier (25), and monitored for progression into more mature lesions, also seen in this model (16, 17) (Figure 3). The smaller lesions likely represent the earliest stages of lesion genesis, never seen clinically in humans. Systematic study of the mechanisms of early lesion genesis and subsequent progression has not been possible in patients because of limitations and serious sampling bias of surgical lesions and very rare human autopsy material. Sampling of early lesions is easily feasible in this model, including multiple lesions from the same brain, and even smaller dilated capillaries not noted on MR imaging, and control capillaries. We have also shown feasibility of LCM of lesional, perilesional and control cells, and isolation of good quality DNA and RNA from these cells for molecular biology studies.

Molecular probes targeted at dividing or activated endothelial cells (1, 3, 26), associated macrophages or other inflammatory cells (2, 11, 12), may allow the specific tagging of CCM lesions and perhaps the monitoring of different disease states, such as earliest stages of hemorrhage or lesion proliferation. Endothelial cells in the CCMs should be accessible to circulating multimodal probes (5), facilitated by the defective blood brain barrier in the lesions (6, 25). Although the aim of the study was to assess the appearance of CCM lesions in vivo and in vitro, and to develop a technique of lesion localization for pathobiologic studies, our mouse models of CCMs are amenable to future applications as a platform for the development and validation of these and other molecular imaging techniques.

In conclusion, we have developed a technique for in vivo and ex vivo imaging of CCMs in Ccm mutant mice using MR. Advantages and limitations of this technique are articulated based on preliminary observations. The model allows the identification, localization and precise sampling of lesions at various stages of their development, including targeted cellular and molecular studies of mechanisms of disease that are impossible to address in humans. Such mechanistic studies will require additional research, and hopefully others will use the techniques for parallel studies.

Grant Information / Other Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by grants K24NS02153 (IAA), S10RR019920 (AMW) and R01NS43543 (DAM) from the National Institutes of Health, and by Pilot and Career Development Grants (IAA) from Evanston Northwestern Healthcare Research Institute.

We gratefully acknowledge Ms. Dinushi Perera for her assistance with mouse breeding and DNA genotyping and the Northwestern University Mouse Phenotyping Core Facility.

Footnotes

This is a non-final version of an article published in final form in Neurosurgery. 2008;63:790-8. Website: http://journals.lww.com/neurosurgery

Financial Disclosures:

None of the authors received any financial support in conjunction with the generation of their submission.

References

- 1.Blankenberg FG, Backer MV, Levashova Z, Patel V, Backer JM. In vivo tumor angiogenesis imaging with site-specific labeled (99m)Tc-HYNIC-VEGF. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2006;33:841–848. doi: 10.1007/s00259-006-0099-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boissonnas A, Fetler L, Zeelenberg IS, Hugues S, Amigorena S. In vivo imaging of cytotoxic T cell infiltration and elimination of a solid tumor. J Exp Med. 2007;204:345–356. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boutry S, Laurent S, Elst LV, Muller RN. Specific E-selectin targeting with a superparamagnetic MRI contrast agent. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2006;1:15–22. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley WG., Jr. MR appearance of hemorrhage in the brain. Radiology. 1993;189:15–26. doi: 10.1148/radiology.189.1.8372185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brekke C, Morgan SC, Lowe AS, Meade TJ, Price J, Williams SC, Modo M. The in vitro effects of a bimodal contrast agent on cellular functions and relaxometry. NMR Biomed. 2007;20:77–89. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clatterbuck RE, Eberhart CG, Crain BJ, Rigamonti D. Ultrastructural and immunocytochemical evidence that an incompetent blood-brain barrier is related to the pathophysiology of cavernous malformations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:188–192. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clatterbuck RE, Elmaci I, Rigamonti D. The nature and fate of punctate (type IV) cavernous malformations. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:26–32. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donehower LA, Harvey M, Slagle BL, McArthur MJ, Montgomery CA, Jr., Butel JS, Bradley A. Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature. 1992;356:215–221. doi: 10.1038/356215a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gault J, Shenkar R, Recksiek P, Awad IA. Biallelic somatic and germ line CCM1 truncating mutations in a cerebral cavernous malformation lesion. Stroke. 2005;36:872–874. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000157586.20479.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jacks T, Remington L, Williams BO, Schmitt EM, Halachmi S, Bronson RT, Weinberg RA. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr Biol. 1994;4:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jander S, Schroeter M, Saleh A. Imaging inflammation in acute brain ischemia. Stroke. 2007;38:642–645. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000250048.42916.ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klohs J, Steinbrink J, Nierhaus T, Bourayou R, Lindauer U, Bahmani P, Dirnagl U, Wunder A. Noninvasive near-infrared imaging of fluorochromes within the brain of live mice: an in vivo phantom study. Mol Imaging. 2006;5:180–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehnhardt FG, von Smekal U, Ruckriem B, Stenzel W, Neveling M, Heiss WD, Jacobs AH. Value of gradient-echo magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of familial cerebral cavernous malformation. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:653–658. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Margolis G, Odom GL, Woodhal B, BM B. The role of small angiomatous malformations in the production of intracerebral hematomas. J Neurosurg. 1951;8:564–575. doi: 10.3171/jns.1951.8.6.0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Otten P, Pizzolato GP, Rilliet B, Berney J. 131 cases of cavernous angioma (cavernomas) of the CNS, discovered by retrospective analysis of 24,535 autopsies [in French] Neurochirurgie. 1989;35:82–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plummer NW, Gallione CJ, Srinivasan S, Zawistowski JS, Louis DN, Marchuk DA. Loss of p53 Sensitizes Mice with a Mutation in Ccm1 (KRIT1) to Development of Cerebral Vascular Malformations. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1509–1518. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63409-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Plummer NW, Squire TL, Srinivasan S, Huang E, Zawistowski JS, Matsunami H, Hale LP, Marchuk DA. Neuronal expression of the Ccm2 gene in a new mouse model of cerebral cavernous malformations. Mamm Genome. 2006;17:119–128. doi: 10.1007/s00335-005-0098-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rigamonti D, Drayer BP, Johnson PC, Hadley MN, Zabramski J, Spetzler RF. The MRI appearance of cavernous malformations (angiomas) J Neurosurg. 1987;67:518–524. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.4.0518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rigamonti D, Johnson PC, Spetzler RF, Hadley MN, Drayer BP. Cavernous malformations and capillary telangiectasia: a spectrum within a single pathological entity. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:60–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson JR, Awad IA, Little JR. Natural history of the cavernous angioma. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:709–714. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.5.0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson JR, Jr., Awad IA, Magdinec M, Paranandi L. Factors predisposing to clinical disability in patients with cavernous malformations of the brain. Neurosurgery. 1993;32:730–736. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199305000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson JR, Jr., Awad IA, Masaryk TJ, Estes ML. Pathological heterogeneity of angiographically occult vascular malformations of the brain. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:547–555. doi: 10.1227/00006123-199310000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rothbart D, Awad IA, Lee J, Kim J, Harbaugh R, Criscuolo GR. Expression of angiogenic factors and structural proteins in central nervous system vascular malformations. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:915–925. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199605000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shenkar R, Sarin H, Awadallah NA, Gault J, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Awad IA. Variations in structural protein expression and endothelial cell proliferation in relation to clinical manifestations of cerebral cavernous malformations. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:343–354. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000148903.11469.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong JH, Awad IA, Kim JH. Ultrastructural pathological features of cerebrovascular malformations: a preliminary report. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:1454–1459. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200006000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu Y, Cai W, Chen X. Near-infrared fluorescence imaging of tumor integrin alpha v beta 3 expression with Cy7-labeled RGD multimers. Mol Imaging Biol. 2006;8:226–236. doi: 10.1007/s11307-006-0041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]