Abstract

Synaptic activities alter synaptic strengths at the axospinous junctions, and such changes are often accompanied by changes in the size of the postsynaptic spines. We have been exploring the idea that drebrin A, a neuron-specific actin-binding protein localized on the postsynaptic side of excitatory synapses, may be a molecule that links synaptic activity to the shape and content of spines. Here, we performed electron microscopic immunocytochemistry with the nondiffusible gold label to explore the relationship among levels of drebrin A, the NR2A subunit of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors, and the size of spines in the perirhinal cortex of adult mouse brains. In contrast to the membranous localization within neonatal spines, most immunogold particles for drebrin A were localized to the cytoplasmic core region of spines in mature spines. This distribution suggests that drebrin within adult spines may reorganize the F-actin network at the spine core, in addition to its known neonatal role in spine formation. Drebrin A-immunopositive (DIP) spines exhibited larger spine head areas and longer postsynaptic densities (PSDs) than drebrin A-immunonegative (DIN) spines (P < 0.001). Furthermore, spine head area and PSD lengths correlated positively with drebrin A levels (r = 0.47 and 0.40). The number of synaptic NR2A immunolabels was also higher in DIP spines than in DIN spines, whereas their densities per unit lengths of PSD were not significantly different. These differences between the DIP and the DIN spines indicate that spine sizes and synaptic protein composition of mature brains are regulated, at least in part, by drebrin A levels.

Indexing terms: electron microscopy, dendritic spine, immunocytochemistry, actin binding protein, postsynaptic density, NMDA receptor

Dendritic spines are small protrusions on dendrites, containing postsynaptic specializations of excitatory synapses. Spine shapes are dynamically regulated by synaptic activity, and shape changes play an important role in synaptic plasticity (Halpain, 2000; Matus, 2000). Spines are enriched in F-actin, and it is proposed that shape changes of spines are regulated via actin-binding proteins (Ethell and Pasquale, 2005).

Drebrin is one of the major F-actin-binding proteins in neurons (Shirao and Obata, 1986; Asada et al., 1994; Ishikawa et al., 1994). There are two drebrin isoforms in mammals, drebrin E and drebrin A (Shirao et al., 1989; Hayashi et al., 1996). Whereas drebrin E is expressed in various cell types and is the dominant isoform in developing brains, drebrin A is specifically expressed in neurons and is the dominant isoform in adult brains (Shirao and Obata, 1986; Shirao et al., 1989; Kojima et al., 1993). In the adult brain, drebrin A is localized mainly to dendritic spines (Shirao et al., 1987; Hayashi et al., 1996).

In cultured neurons, drebrin A and F-actin cocluster at postsynaptic sites prior to the emergence of postsynaptic density (PSD)-95 clusters (Takahashi et al., 2003), and drebrin knockdown results in the decrease of spine densities (Takahashi et al., 2006). In neonatal rat brains, drebrin A is preferentially localized at the submembranous surfaces of nascent synapses (Aoki et al., 2005). At later stages of development, overexpression of drebrin A in vitro results in the elongation of spines in mature neurons (Hayashi and Shirao, 1999), and drebrin knockdown decreases the head widths of formed spines (Takahashi et al., 2006). These observations indicate that drebrin is important for spine formation and for morphological changes of formed spines.

Beside its role in spine morphology, drebrin may be involved in spine functions. Upon induction of long-term potentiation (LTP), a known form of synaptic plasticity, expression of drebrin is enhanced at stimulated neuropil regions in vivo, and this is accompanied by the accumulation of F-actin in dendritic spines (Fukazawa et al., 2003). This suggests increases of F-actin and drebrin at stimulated synapses in vivo, and the increases may contribute to the enlargement of individual spines, a phenomenon seen following LTP induction in vitro (Matsuzaki et al., 2004). Drebrin A expression level also seems to be linked to the stability of spines within mature brains. Disappearance of drebrin A occurs prior to the spine loss from various brain regions of Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome patients (Harigaya et al., 1996; Hatanpaa et al., 1999; Shim and Lubec, 2002). The studies using animal model of Alzheimer’s disease also indicate that drebrin level declines as the disease advances toward terminal symptoms (Calon et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2006). Drebrin expression levels decrease even during normal aging (Hatanpaa et al., 1999). Altogether, these observations suggest that drebrin A may be a molecule that links synaptic activity to the spine morphology, with the lack of drebrin in spines relating to cognitive defect in neurological disorders and with the accumulation of drebrin A within spine heads relating to the activity-dependent enlargement of spine size.

Electron microscopic immunocytochemistry (EM-ICC) that uses the horseradish peroxidase/diaminobenzidine (HRP/DAB) as the immunolabel shows drebrin within the great majority but not all of spines in the adult rat cerebral cortex (Aoki et al., 2005). When the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors are chronically blocked with NMDA receptor antagonists, the unlabeled spines are decreased dramatically, in addition to accumulation of NR2A subunit of NMDA receptors (Fujisawa et al., 2006). These results indicate that the portion of spines that remains unlabeled at basal state cannot be due, entirely, to failures in immunodetection. However, neither of these studies attempted to correlate drebrin A levels to their sizes. Thus, in the present study, we analyzed the relationship among drebrin A content, NR2A content, and sizes of spines, as well as the sub-cellular localization of drebrin A within them, in adult mouse cortex by using EM-ICC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

C57BL mice were purchased from Charles River (Tsukuba, Japan) and bred and housed in the animal center of Gunma University Graduate School of Medicine in accordance with the guidelines published in the NIH Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. All experiments were carried out according to the Animal Care and Experimentation Committee of Gunma University, Showa Campus.

Tissue processing

The animals (five males, 14 weeks) were perfused transcardially first with 0.9% NaCl and 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4; PBS) containing 80 U/ml of heparin, followed by a fixative mix consisting of 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.1% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4; PB). The brains were removed and cut into 40-μm coronal sections with a vibratome. Aldehyde fixation was terminated by reacting free-floating sections with 1% sodium borohydride in PB. After being rinsed in PB, brain sections were stored in PBS containing 0.05% sodium azide (PBS-azide) at 4°C to prevent bacterial growth. The sections were freeze-thawed prior to the immunocytochemistry procedure, in order to enhance penetration of histological reagents (Wouterlood and Jorritsma-Byham, 1993; Aoki et al., 2003).

Characterization of antibodies

The rabbit antidrebrin A antibody DAS2 was generated against the peptide unique to the adult form of drebrin (residues 325–336), which is identical among mouse, rat, and human. This antibody was affinity purified by the antigen peptide and previously shown by Western blotting to recognize a single band corresponding to drebrin A but not the band corresponding to the embryonic isoform, drebrin E (Aoki et al., 2005). Specific labeling of drebrin A within aldehyde-fixed tissue was demonstrated by elimination of immunoreactivity in rat brain tissue, when preadsorbed by the synthetic peptide used to generate the antiserum (Aoki et al., 2005).

Rabbit polyclonal anti-NR2A antibody (Upstate, Lake Placid, NY; catalog No. 07-632, lot 27085) was generated by using 6His-tagged fusion protein corresponding to amino acids 1,265–1,464 of mouse NR2A as immunogen, and it has been shown to cross-react with rat NR2A (manufacturer’s technical information). This antibody has been shown to be useful for NR2A labeling by the PEG method on ferret brain tissue, using the same protocol as that used in the present study (Erisir and Harris, 2003). In addition, we counted the number of PEG particles at asymmetric (presumably excitatory) and symmetric (presumably inhibitory) synapses and confirmed a remarkable difference in the amount of labeling between them (1.80 particles/synapse for asymmetric vs. 0.36 particles/synapse for symmetric synapses). Since at least a portion of the apparently symmetric synapses were probably asymmetric (excitatory), this difference in the degree of immunolabeling reflects clear differentiation of labeling across the two types of synapses.

The mouse monoclonal antidrebrin antibody M2F6 was generated by fusion of mouse myeloma cell X-63-Ag-8-653 with Balb/c mouse splenocyte immunized with purified chicken drebrin E2, an avian-specific subtype of drebrin E (Shirao and Obata, 1986; for review see Shirao et al., 1990). This antibody recognizes the amino acid sequence in the C-terminal region that is common to drebrin E and drebrin A. Western blot shows that this antibody reacts with drebrin E and A of mouse, rat, cat, and human brain tissues (Shirao et al., 1989; Imamura et al., 1992; Asada et al., 1994; Harigaya et al., 1996), and with drebrins E1, E2, and A of chicken (Shirao and Obata, 1986; Shirao et al., 1990).

Mouse monoclonal anti-PSD-95 antibody (Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO; catalog No. MA1-046) was generated against the purified recombinant rat PSD-95. The antibody has been used widely to detect PSD-95 in a variety of preparations from rats and mice, and it stains a single band at ~95 kDa representing PSD-95 from mouse brain extracts on Western blot (Vazquez et al., 2004).

Immunocytochemistry

Immunocytochemistry employed a rabbit polyclonal antidrebrin A antibody, DAS2. Two preembedding electron microscopic immunolabeling procedures were used for detecting drebrin A in spines: the silver-intensified gold (SIG) method for the analysis of drebrin A distribution within spines and the HRP/DAB method to maximize the detection of drebrin A. For both labeling procedures, sections were incubated in 1% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 30 minutes and rinsed in PBS. These sections were incubated in a blocking buffer, consisting of 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS-azide to minimize nonspecific labeling. The same sections were then incubated in DAS2, diluted 1:1,000 in PBS-BSA-azide, overnight at room temperature under constant agitation.

For HRP/DAB labeling, biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vector, Burlingame, CA; 1:100) and the standard ABC Elite kit (Vector) were used. The sections were post-fixed by using 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes, then with 1% osmium tetroxide in PB for 1 hour and 4% uranyl acetate in 70% ethanol for 1–3 days. Uranyl acetate works as a fixative, following glutaraldehyde and osmium textroxide (Glauert, 1975; Kharazia and Weinberg, 1993). In our study, there was no detectable difference in the immunocytochemistry and ultrastructure between 1 day and 3 days of treatment with uranyl acetate. Therefore, the data collected from tissues treated with uranyl acetate for different lengths of time were combined for the statistical analysis. After these steps, the sections were embedded in Epon 812 (EMS, Hatfield, PA).

For SIG labeling, sections that had undergone incubation in DAS2 were rinsed, then incubated in PBS-BSA-azide containing 0.8 nm colloidal gold-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (EMS) for 4 hr. Subsequent to rinsing, these sections were postfixed with 1% glutaraldehyde for 10 minutes. The colloidal gold particles were intensified with the silver IntenSE M kit (Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL). The tissues underwent osmium-free tissue processing (Phend et al., 1995) and were embedded in Epon 812. The EM-ICC procedure for drebrin A is described in greater detail elsewhere (Aoki et al., 2005).

For double labeling of drebrin A and the NR2A subunit of NMDA receptors, preembedding and postembedding methods were used with tissues from three animals. The tissues were labeled for drebrin A by the SIG-staining method, as described above, and were followed by Phend’s postembedding gold labeling (PEG; Phend et al., 1995) for the immunodetection of the NR2A subunit. The ultrathin sections of tissue labeled for drebrin A by the SIG labeling were collected on formvar-coated grids. Grids were rinsed in 50 mM Tris buffer containing 0.9% NaCl and 0.1% Triton X-100 (TBST; pH 7.4), then incubated overnight in rabbit anti-NR2A antibody diluted 1:15 using TBST (pH 7.4). After rinsing in TBST (pH 7.4), the grids were incubated in goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to 10-nm gold particles (EMS; 1:25 in TBST, pH 8.2). The grids were washed, postfixed in 2% glutaraldehyde for 10 min, and counterstained with Reynold’s lead citrate (EMS). Adjacent ultrathin sections that served as controls underwent the identical postembedding immunolabeling procedure, except that the first TBST (pH 7.4) incubation contained no NR2A antibody.

Ultrastructural analysis

Immunoprocessed tissues were cut into thin sections (~80 nm) with an ultramicrotome and examined under the electron microscope (EM; 1200XL; JEOL, Tokyo, Japan). We chose to focus our analysis on layer I of the perirhinal cortex at the level of 1.82–2.46 mm posterior to bregma, in accordance with Franklin and Paxinos (1997). This region was chosen because it exhibited intense uniform immunoreactivity for drebrin A and because the rhinal fissure could be used as an anatomical landmark. Since the fixation condition used for the study yielded excellent preservation of the ultrastructure, we were able to restrict our sampling of synapses to the tissue–resin interface of the ultrathin sections, where penetration by immunoreagents would be optimal (Aoki et al., 2005).

Asymmetric synapses were identified by the juxtaposition of two plasma membranes, with the presence of synaptic vesicles in the presynaptic terminal and the presence of electron-dense PSDs in the opposing postsynaptic profile. We excluded postsynaptic structures containing mitochondria and microtubules, so we could be sure to exclude dendritic shafts from our sample. Synapses for which only a part of the spine was visible in the micrographs were also excluded from our study, because measurement of spine head area required a full contour of well-defined plasma membranes.

HRP/DAB labeling was used to determine the proportion of spines with drebrin A. Images were captured on negatives at a magnification of ×15,000, and a total area of 800–900 μm2 per animal was sampled. More than 200 synapses were counted from tissue of each animal.

SIG-labeled sections were used to determine drebrin A content and its distribution within single spines and for measuring spine head areas and PSD lengths. The same set of micrographs was used for both analyses. Images were captured digitally by using the Hamamatsu CCD camera and the AMT data acquisition system (Advantage Plus Digital CCD Camera System; AMT, Danvers, MA) at a magnification of ×30,000. At least 11 nonoverlapping fields each covering 19.4 μm2 were captured for each animal. More than 100 synapses were counted in each animal. The spine head areas and PSD lengths were measured in ImageJ (public domain software). Details of the analysis of SIG localization within the spine head are given in Results (Fig. 3).

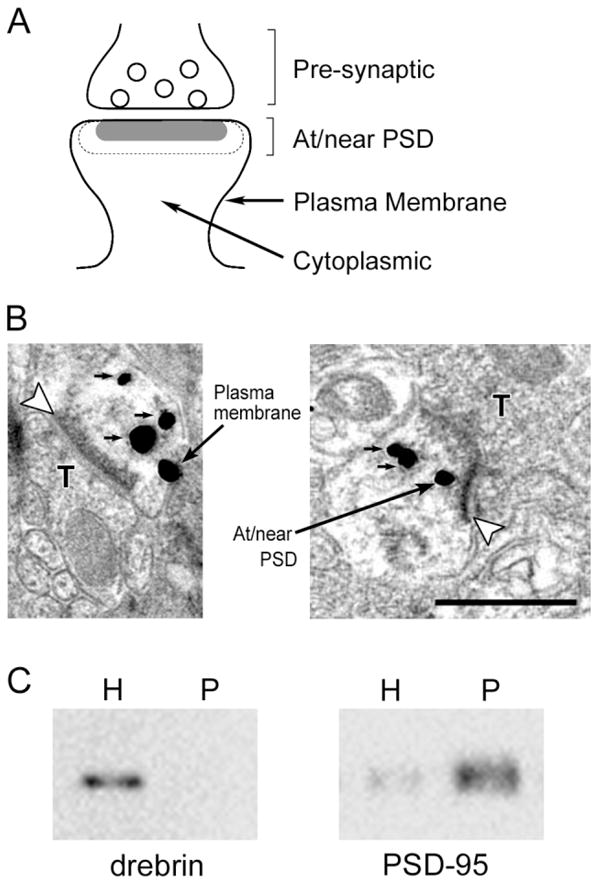

Fig. 3.

Localization of drebrin A within a spine. A: Schematic drawing of a synaptic profile, showing mutually exclusive categories of postsynaptic zones used in the analysis. Any gold particles residing within dotted-line area, the area within twice the thickness of the PSD from the synaptic cleft, were categorized as “at/near PSD.” The gold particles that were attached to the plasma membrane excluding PSD area were categorized as “plasma membrane,” and particles found within the spine core were categorized as “cytoplasmic.” B: Examples of SIG immunogold labeling for drebrin A. Open arrowheads indicate asymmetric synapses. SIG particles at “plasma membrane” and “at/near PSD” categories are indicated by large arrows. SIG particles with small arrows belong to the “cytoplasmic” category. T, presynaptic terminal. C: Immunoblot analysis of crude homogenate (H) and PSD fraction (P); 1.5 μg of protein was loaded in each lane. Note that drebrin is not found in the PSD fraction. Scale bar = 500 nm.

PEG-labeled sections were used to determine the localization of NR2A within spines. Images were captured digitally, in the same way as for the SIG-labeled sections described above, at a magnification of ×30,000. At least 13 nonoverlapping fields each covering 19.4 μm2, from at least two grids, were captured from tissue of each animal. In total, 378 randomly chosen synapses were analyzed.

The results were statistically evaluated in Statistica software (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK). The significance of differences was tested by using the Mann-Whitney U-test and Student’s t-test. To determine the degree of correlation, Spearman rank correlation was used. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Photomicrograph presentation

Images were captured digitally or directly on electron microscopic negatives, as described above. Adjustments to the images, including size, brightness, and contrast, were carried out in Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (San Jose, CA).

Subcellular fractionation

As an alternative approach to quantifying the relative amounts of drebrin A at the PSD, subcellular fractionation was performed. PSD fraction was isolated by using the swing bucket protocol described by Villasana et al. (2006). In brief, cerebral cortices were isolated from three adult mice and homogenized in synaptoneurosome buffer (10 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, pH 7.0) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Complete minus EDTA; Roche, Penzberg, Germany) at 4°C. The homogenate was diluted further with the same volume of synaptoneurosome buffer, sonicated, and then filtered twice through three layers of prewetted 100-μm-pore nylon filter (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The resulting filtrate was filtered again through a prewetted 5-μm-pore PVDF hydrophilic filter (Millipore) and centrifuged at 1,000g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The pellet, corresponding to the synaptoneurosome fraction, was resuspended in the suspension buffer containing 0.32 M sucrose and 1 mM NaHCO3 (pH 7.0).

Isolated synaptoneurosome was diluted with 1% Triton X-100 in 32 mM sucrose and 12 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.1). The sample was stirred at 4°C for 15 minutes and centrifuged at 33,000g for 20 minutes. The resulting pellet was resuspended with the suspension buffer and loaded onto a discontinuous sucrose gradient containing 1.5 M and 1.0 M sucrose. After centrifugation at 167,000g for 2 hours, the pellet was resuspended in the buffer, diluted with an equal amount of 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM KCl, and then centrifuged at 167,000g for 30 minutes. The resulting pellet resuspended in the buffer was considered as the PSD fraction.

Protein concentration was measured, and 1.5 μg of proteins from each fraction was loaded in each lane on a 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel for subsequent immunoblot analysis. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore) and probed with M2F6 (1:2) and anti-PSD-95 (1: 2,000) monoclonal antibodies. The bands of immonoreactive proteins were detected by using the ECL Western Blotting Detection System (Amersham, Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom). The chemiluminescence image was obtained with a cooled CCD camera system (Light-Capture; ATTO, Tokyo, Japan). Further details of the immunoblot procedure are given elsewhere (Hayashi et al., 1998; Aoki et al., 2005).

RESULTS

Drebrin A immunoreactivity is localized at the postsynaptic side of asymmetric synapses in mouse cerebral cortex

We analyzed the perirhinal cortex layer I of the mice tissues that were immunolabeled for drebrin A by using HRP/DAB (Fig. 1) and SIG (Fig. 2A) methods. With either immunolabeling method, drebrin A immunoreactivity was found only on the postsynaptic spines and dendritic shafts and never on the presynaptic side. Both immunocytochemical procedures yielded a mixture of immunolabeled and unlabeled spines within a single field. Since HRP/DAB labeling is diffusible and enzymatically amplified, thereby allowing for better detection of antigens, we used HRP/DAB-labeled tissue to determine the proportion of spines with drebrin A. One hundred twenty-four nonoverlapping fields along the tissue–resin interface, covering 4,534 μm2 of the neuropil, were sampled. Within this area of neuropil, 80% ± 7% of asymmetric synapses (n = 5 animals) were detectably immunolabeled for drebrin A. These observations were consistent with previous reports of adult rat neocortex and hippocampus (Aoki et al., 2005) and mouse somatosensory cortex (Mahadomrongkul et al., 2005), immunolabeled with the same antibody.

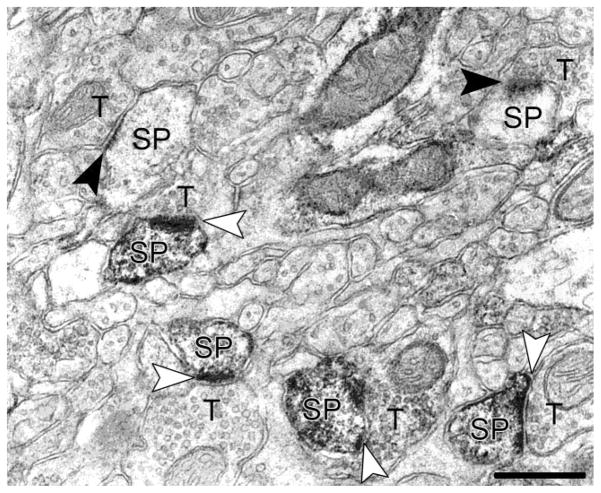

Fig. 1.

Ultrastructural localization of drebrin A in dendritic spines, as visualized by horseradish peroxidase/diaminobenzidine (HRP/DAB) staining. Arrowheads point to asymmetric synapses, which were identified by the presence of PSDs and presynaptic terminals containing synaptic vesicles on opposing sides. Both drebrin A-immunolabeled synapses (open arrowheads) and unlabeled synapses (solid arrowheads) are found in the same field. Note that drebrin A immunoreactivity is found on dendritic spines but not on presynaptic terminals. SP, dendritic spine; T, presynaptic axon terminal. Scale bar = 500 nm.

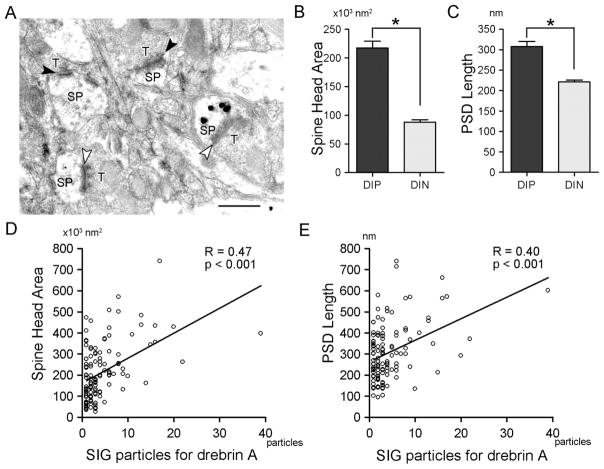

Fig. 2.

Cross-sectional head area and PSD lengths of drebrin A-immunopositive (DIP) and -immunonegative (DIN) spines. A: Typical example of electron micrographs, showing drebrin A immunolabeling by SIG staining. SIG particles were found in spines but not in presynaptic terminals. Open arrowheads and solid arrowheads indicate immunolabeled and unlabeled synapses, respectively. SP, dendritic spine; T, presynaptic terminal. B,C: Mean cross-sectional spine head area (B) and PSD length (C) were significantly larger in DIP spines than in DIN spines (*P < 0.001, Mann-Whitney U-test). D,E: There are positive correlations between the number of SIG particles immunolabeling for drebrin A and spine head area (P < 0.001, Spearman rank correlation; D) and between the number of SIG particles and PSD length (P < 0.001, Spearman rank correlation; E). Scale bar = 500 nm.

Drebrin A-immunopositive (DIP) spines are larger than drebrin A-immunonegative (DIN) spines

We analyzed drebrin A content within spines by using two-dimensional (2-D) SIG-labeling images. Although the SIG procedure suffers from significantly lower detection level compared with the HRP/DAB method, the SIG procedure allow us to estimate the relative amount of antigens and location of antigenic sites within spines (Chan et al., 1990; Aoki et al., 2000). The size of SIG particles varies, from single particle to cluster of particles, which appeared as a large mass with uneven surfaces. We considered spines containing even single gold particle as DIP spines, because we rarely found even a single gold particle on presynaptic side. To obtain accurate SIG particle counts, we outlined the SIG clusters and identified the number of evenly round particles making up the cluster. Among 479 postsynaptic spines encountered, 21% ± 2% (n = 4 animals) were detectably immunolabeled for drebrin A. The mean number of SIG particles in each DIP spine was 4.1 ± 0.3 (n = 136 spines).

Previous in vitro studies have shown that overexpression of drebrin A in developing neurons induces morphological changes of spines (Hayashi and Shirao, 1999; Mizui et al., 2005), whereas knockdown of drebrin A expression suppresses morphological maturation of spines (Takahashi et al., 2006). We wanted to explore the physiological roles of drebrin A as it affects morphology of single spines within intact neurons of adult brains. To this end, we classified spines based on the presence/absence of detectable levels of drebrin A immunoreactivity by the SIG method, then quantitatively examined the cross-sectional areas of spine heads and lengths of PSDs of each subpopulation. These 2-D parameters are representative of the volumes of spines and so can be used to detect the differences in spine head size (Toni et al., 2001; Meng et al., 2002).

The spine head area of DIP spines was 217 ± 12 × 103 nm2 (n = 120 spines), and PSD length was 308 ± 12 nm (n = 120 spines; Fig. 2B,C). The spine head area of DIN spines was 88 ± 4 × 103 nm2 (n = 359 spines), and PSD length was 221 ± 5 nm (n = 359 spines). Nonparametric Mann-Whitney U-test revealed that spine head area and PSD length were significantly larger (P < 0.001) and longer (P < 0.001) in DIP spines than in DIN spines (Fig. 2B,C).

It is known that perforated synapses are larger than nonperforated synapses (Calverley and Jones, 1990; Jones and Harris, 1995; Muller, 1997; Toni et al., 2001). Because DIP spines had larger spine head area and longer PSD than DIN spines, we hypothesized that DIP spines may have more perforated synapses than DIN spines. The average proportion of perforated synapses for DIP vs. DIN spines was determined by taking a tally for groups of 10 randomly encountered synapses. As a result, DIP spines contained more perforated synapses (20% ± 3%, n = 11 groups) than DIN spines (6% ± 1%, n = 35 groups, P < 0.001).

Spine head area and PSD length correlate with drebrin A content

Next, we examined whether drebrin A content in the spine correlates with spine size. There was a significant positive correlation between the number of SIG particles for drebrin A and spine head area (the correlation coefficient R = 0.47, n = 118; Spearman rank correlation, P < 0.001; Fig. 2D) as well as between the number of SIG particles and PSD length (the correlation coefficient R = 0.40, n = 118; Spearman rank correlation, P < 0.001; Fig. 2E).

Drebrin A is localized mainly in the cytoplasmic area of dendritic spines

To analyze the distribution of drebrin A within spines, the spine head was subdivided into three mutually exclusive regions: “at/near PSD,” “plasma membrane,” and “cytoplasmic” regions. “At/near PSD” region was defined as PSD and its bounded cytoplasmic area with the width equivalent to the thickness of PSD. The rest of the spine head was categorized into “plasma membrane” region if the SIG was on the plasma membrane but away from the PSD and “cytoplasmic” region if SIG was neither on the plasma membrane nor in the “at/near PSD” region (Fig. 3A,B). We tallied the number of gold particles in each postsynaptic region for every group of 10 randomly chosen spines, and the average percentage of gold in each region was calculated (Fujisawa and Aoki, 2003).

The percentage of drebrin A immunolabeling in the “cytoplasmic” region was the highest (56% ± 3%, n = 13 groups) among the three regions. In the remaining two regions, the percentage in the “at/near PSD” region (25% ± 3%, n = 13 groups) was higher than that in the “plasma membrane” region (15% ± 3%, n = 13 groups). Immunoblot analysis of cerebral cortex showed undetectable drebrin A immunoreactivity in the PSD fraction (Fig. 3C), which was consistent with the larger number of SIG particles for drebrin A in the “cytoplasmic” region by the EM-ICC.

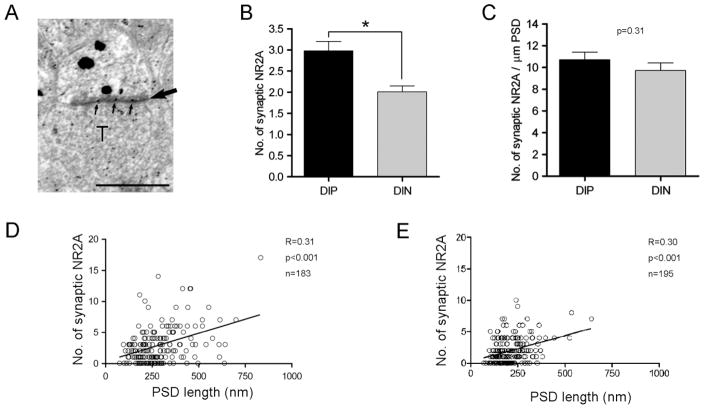

Comparison of the amount of synaptic NR2A between DIP and DIN spines

We used drebrin A and NR2A dual labeling to analyze whether there might be any difference in the amount of synaptic NMDA receptors between the spines with and without drebrin A immunoreacitivity. Spines were classified into DIP and DIN spines by SIG staining, and the numbers of PEG at PSDs, which represent the amount of synaptic NMDA receptors, were compared between them. The number of synaptic NR2A of DIP spines (3.0 ± 0.2; n = 183 spines) was significantly greater than that of DIN spines (2.0 ± 0.1; n = 195 spines; Student’s t-test, P < 0.001; Fig. 4B). The density of synaptic NR2A (the number of NR2A particles per unit PSD length) of DIP spines was 10.7 ± 0.7 particles/μm PSD and was not significantly different from that of DIN spines (9.7 ± 0.7 particles/μm PSD; Student’s t-test, P = 0.31; Fig. 4C). This indicates that the greater association of NR2A with DIP spines can be explained fully by their longer PSDs.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the amount of synaptic NR2A between DIP and DIN spines. A: Dual-labeling image of drebrin A and the NR2A subunit of NMDA receptors. Drebrin A (large particles) was labeled by the SIG method, and NR2A (small particles) was labeled by the PEG method. The NR2A immunogold particles on the PSD (small arrows) were considered as synaptic NR2A and analyzed in this study. A large arrow points to the PSD. T, presynaptic terminal. B: The number of NR2A particles at the PSD of DIP and DIN spines. DIP spine contains a larger number of synaptic NR2A particles than DIN spine (*P < 0.05, Student’s t-test). C: The density of synaptic NR2A particles (the number of synaptic NR2A particles per μm of PSD) was not different between DIP and DIN spines (P = 0.31, Student’s t-test). D,E: Correlation between the number of synaptic NR2A immunogold and PSD length of DIP (D) and DIN (E) spines. There is a positive correlation between synaptic NR2A immunolabeling and PSD length in both DIP and DIN spines (P < 0.001, Spearman rank correlation). Scale bar = 500 nm.

We also analyzed the relationship between the synaptic NR2A content and the PSD length. The number of NR2A particles correlated with the PSD length both in DIP spines (correlation coefficient R = 0.31, P < 0.001; Fig. 4D) and in DIN spines (the correlation coefficient R = 0.30, P < 0.001; Fig. 4E).

DISCUSSION

The present study reveals that the spines containing drebrin A immunoreactivity are larger, and the spine size correlates with drebrin A content in adult brain. In contrast to the case in immature spines, drebrin A in mature spines is not enriched at the plasma membrane. Synaptic NMDA receptors are accumulated more in larger DIP spines.

By the use of 2-D SIG-labeling images, we show that DIP spines have significantly larger head area than DIN spines in adult intact mouse brains. In addition, DIP spines have significantly longer PSDs and a higher percentage of perforated synapses than DIN spines. PSD length is known to correlate with spine size (Trommald and Hulleberg, 1997; Toni et al., 2001; Meng et al., 2002; Fujisawa et al., 2006), and perforated synapses are larger than those of nonperforated (simple) synapses (Calverley and Jones, 1990; Jones and Harris, 1995; Muller, 1997; Toni et al., 2001). Our results are the first to show that larger spine head areas, longer PSDs, and perforated PSDs are associated with another characteristic, abundance of drebrin A.

Although the correlations between the mount of drebrin A and spine or synapse size were statistically significant, the data show considerable variability, particularly for low numbers of gold particles. We are unable to judge whether this variability in the number of gold particles indicates high variability in the actual levels of drebrin A or is due to technical limitations. Low levels of drebrin could very well be undetectable, as with any immunocytochemical labeling.

One possible mechanism underlying the difference in spine size between DIP and DIN spines is that the accumulation of drebrin A in spines enlarges their sizes. Positive correlation between drebrin content in each spine and its PSD length supports this idea. Drebrin is thought to be involved in the dynamics of actin cytoskeleton through inhibition of actin–myosin interaction (Hayashi et al., 1996; Cheng et al., 2000) and competition for other actin-binding proteins, including tropomyosin, α-actinin (Ishikawa et al., 1994), and fascin (Sasaki et al., 1996). The alteration of actin dynamics via drebrin A may enable enlargement of spines by mechanism yet to be identified. In support of the idea that drebrin A enables spine enlargement, in vitro studies demonstrate that overexpression of drebrin A elongates spines in mature neurons (Hayashi and Shirao, 1999) and changes filopodia into aberrantly enlarged megapodia in immature neurons (Mizui et al., 2005). Conversely, suppression of drebrin A expression reduces spine density and results in the formation of thin, immature spines (Takahashi et al., 2006).

Another possibility is that drebrin A moves into the spines that are already enlarged, because larger spines have a higher capacity for proteins and receptors. The accumulation of PSD-95, a major component of PSD, is suppressed in the spines lacking drebrin (Takahashi et al., 2003). This observation suggests that drebrin-dependent actin clustering in spines governs PSD-95 accumulation within spines. However, the possibility that PSD-95 may accumulate by a drebrin A-independent mechanism, simply as a result of spine enlargement, cannot be ruled out entirely.

The proportion of DIP spines determined in this study by HRP/DAB staining was comparable to previous finding (Aoki et al., 2005), suggesting that the proportion of DIP spines in vivo is fairly constant. Then, what separates DIN spines and DIP spines? We have shown that activation of NMDA receptors induces the translocation of drebrin from spines to their parent dendrite (Sekino et al., 2006). Conversely, inhibition of NMDA receptors in vivo facilitates the accumulation of drebrin A within spines (Fujisawa et al., 2006). These findings indicate that drebrin A changes its intracellular localization in response to NMDA receptor activation. Differences between DIP and DIN spines may be the reflection of the recent history of NMDA receptor activation of the spine.

The present study shows that DIP spines have a greater number of synaptic NR2A than DIN spines. One may expect that drebrin A positively regulates the accumulation of NR2A at spines. However, the density of NR2A on PSDs is not different between DIP and DIN spines, and the number of synaptic NR2A correlates positively with PSD lengths in DIP spines, as in DIN spines. Therefore, accumulation of NR2A at synapses is more likely to depend on spine size rather than on drebrin A. This is consistent with our previous finding that drebrin A is not necessary for the accumulation of NMDA receptors under normal physiological conditions (Takahashi et al., 2006), although it is necessary for the homeostatic synaptic accumulation of NMDA receptors in neurons treated chronically or acutely with APV (Rao and Craig, 1997; Aoki et al., 2003; Takahashi et al., 2006).

Drebrin A in adult brains is not enriched at the plasma membrane, and this is different from the membranous localization in immature neurons (Aoki et al., 2005). The alteration in drebrin A distribution suggests the differential role of drebrin A between mature and immature neurons; drebrin A may be involved in spine formation at the early stage of neuronal development, while it regulates the remodeling of cytoplasmic F-actin for synaptic plasticity in mature neurons.

As far as noncytoplasmic drebrin A is concerned, drebrin A immunolabeling in adult brain is relatively stronger at the synaptic PSD region. Immunoblot analysis of larger amounts of protein samples (12 μg) reveals that drebrin exists in the PSD fraction (Suzuki et al., 2001), although we failed to detect drebrin in our PSD samples, possibly because of the limits for detection. Drebrin A strengthens cell–substratum contact by increasing the stability of cell adhesion plaques in vitro (Ikeda et al., 1995, 1996), and drebrin A is localized at submembranous regions in the nascent axodendritic contact sites during development in vivo (Aoki et al., 2005). Furthermore, drebrin E (a splice variant of drebrin) in nonneuronal cells is specifically enriched at cell–cell junctions (Peitsch et al., 1999) and is required for maintaining connexin43-containing gap junctions in their functional state at the plasma membrane (Butkevich et al., 2004). Therefore, drebrin A localized in the synaptic PSD region may also contribute to stabilizing synaptic contacts.

Given that larger spines are relatively persistent over days to months in vivo (Holtmaat et al., 2005) and relatively stable to the stimulus in vitro (Matsuzaki et al., 2004), drebrin may be contributing to the stability of spines by altering their sizes. Decrease in drebrin expression level has been reported in several neurological disorders associated with cognitive deficits, such as Alzheimer’s disease (Harigaya et al., 1996) and Down syndrome (Shim and Lubec, 2002), as well as in normal aging (Hatanpaa et al., 1999). Alzheimer’s disease model mice showed relatively constant areal density of DIP spines from 3 to 18 months and beyond for both genotypes, although the areal density of DIN spines fluctuates (Mahadomrongkul et al., 2005). This finding supports the idea that large DIP spines are more stable against the neurotoxic factors than the DIN spines. Given the abnormal expression of drebrin A in neurological disorders, it will be interesting to examine whether the drebrin-dependent synaptic events, such as the regulation of actin dynamics and the change of spine morphology suggested in the present study, are disturbed in the brains of animal models of neurological disorders and to explore mechanisms that cause synaptic dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MEXT); Grant number: 17023008; Grant sponsor: Japan-U.S. Brain Research Cooperative Program (to T.S.); Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant number: R01NS41091 (to C.A.); Grant number: R01EY13145 (to C.A.); Grant number: P30EY13079 (to C.A.).

We thank Sho Fujisawa for her help with statistics, Veera Mahadomrongkul for technical support, and Makoto Ito and Kenji Hanamura for critical reading of the manuscript.

LITERATURE CITED

- Aoki C, Rodrigues S, Kurose H. Use of electron microscopy in the detection of adrenergic receptors. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;126:535–563. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-684-3:535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki C, Fujisawa S, Mahadomrongkul V, Shah PJ, Nader K, Erisir A. NMDA receptor blockade in intact adult cortex increases trafficking of NR2A subunits into spines, postsynaptic densities, and axon terminals. Brain Res. 2003;963:139–149. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03962-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki C, Sekino Y, Hanamura K, Fujisawa S, Mahadomrongkul V, Ren Y, Shirao T. Drebrin A is a postsynaptic protein that localizes in vivo to the submembranous surface of dendritic sites forming excitatory synapses. J Comp Neurol. 2005;483:383–402. doi: 10.1002/cne.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asada H, Uyemura K, Shirao T. Actin-binding protein, drebrin, accumulates in submembranous regions in parallel with neuronal differentiation. J Neurosci Res. 1994;38:149–159. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490380205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butkevich E, Hulsmann S, Wenzel D, Shirao T, Duden R, Majoul I. Drebrin is a novel connexin-43 binding partner that links gap junctions to the submembrane cytoskeleton. Curr Biol. 2004;14:650–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calon F, Lim GP, Yang F, Morihara T, Teter B, Ubeda O, Rostaing P, Triller A, Salem N, Jr, Ashe KH, Frautschy SA, Cole GM. Docosahexaenoic acid protects from dendritic pathology in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Neuron. 2004;43:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calverley RK, Jones DG. Contributions of dendritic spines and perforated synapses to synaptic plasticity. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 1990;15:215–249. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(90)90002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan J, Aoki C, Pickel VM. Optimization of differential immunogold-silver and peroxidase labeling with maintenance of ultrastructure in brain sections before plastic embedding. J Neurosci Methods. 1990;33:113–127. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(90)90015-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng X-T, Hayashi K, Shirao T. Non-muscle myosin IIB-like immunoreactivity is present at the drebrin-binding cytoskeleton in neurons. Neurosci Res. 2000;36:67–173. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(99)00123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erisir A, Harris JL. Decline of the critical period of visual plasticity is concurrent with the reduction of NR2B subunit of the synaptic NMDA receptor in layer 4. J Neurosci. 2003;23:5208–5218. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-05208.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethell IM, Pasquale EB. Molecular mechanisms of dendritic spine development and remodeling. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;75:161–205. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin K, Paxinos G. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. San Diego: Academic Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa S, Aoki C. In vivo blockade of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors induces rapid trafficking of NR2B subunits away from synapses and out of spines and terminals in adult cortex. Neuroscience. 2003;121:51–63. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00341-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa S, Shirao T, Aoki C. In vivo, competitive blockade of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors induces rapid changes in filamentous actin and drebrin a distributions within dendritic spines of adult rat cortex. Neuroscience. 2006;140:1177–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukazawa Y, Saitoh Y, Ozawa F, Ohta Y, Mizuno K, Inokuchi K. Hippocampal LTP is accompanied by enhanced F-actin content within the dendritic spine that is essential for late LTP maintenance in vivo. Neuron. 2003;38:447–460. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauert AM. Fixation, dehydration and embedding of biological specimens: practical methods in electron microscopy. Amstersam: North-Holland; 1975. p. 207. [Google Scholar]

- Halpain S. Actin and the agile spine: how and why do dendritic spines dance? Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:141–146. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01576-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harigaya Y, Shoji M, Shirao T, Hirai S. Disappearance of actin-binding protein, drebrin, from hippocampal synapses in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 1996;43:87–92. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490430111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatanpaa K, Isaacs KR, Shirao T, Brady DR, Rapoport SI. Loss of proteins regulating synaptic plasticity in normal aging of the human brain and in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1999;58:637–643. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199906000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Shirao T. Change in the shape of dendritic spines caused by overexpression of drebrin in cultured cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3918–3925. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-10-03918.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Ishikawa R, Ye LH, He XL, Takata K, Kohama K, Shirao T. Modulatory role of drebrin on the cytoskeleton within dendritic spines in the rat cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 1996;16:7161–7170. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-22-07161.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi K, Suzuki K, Shirao T. Rapid conversion of drebrin isoforms during synapse formation in primary culture of cortical neurons. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;111:137–141. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtmaat AJ, Trachtenberg JT, Wilbrecht L, Shepherd GM, Zhang X, Knott GW, Svoboda K. Transient and persistent dendritic spines in the neocortex in vivo. Neuron. 2005;45:279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Shirao T, Toda M, Asada H, Toya S, Uyemura K. Effect of a neuron-specific actin-binding protein, drebrin A, on cell–substratum adhesion. Neurosci Lett. 1995;194:197–200. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11760-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda K, Kaub PA, Asada H, Uyemura K, Toya S, Shirao T. Stabilization of adhesion plaques by the expression of drebrin A in fibroblasts. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;91:227–236. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00181-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamura K, Shirao T, Mori K, Obata K. Changes of drebrin expression in the visual cortex of the cat during development. Neurosci Res. 1992;13:33–41. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(92)90032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa R, Hayashi K, Shirao T, Xue Y, Takagi T, Sasaki Y, Kohama K. Drebrin, a development-associated brain protein from rat embryo, causes the dissociation of tropomyosin from actin filaments. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29928–29933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DG, Harris RJ. An analysis of contemporary morphological concepts of synaptic remodeling in the CNS: perforated synapses revisited. Rev Neurosci. 1995;6:177–219. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.1995.6.3.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kharazia VN, Weinberg RJ. Glutamate in terminals of thalamocortical fibers in rat somatic sensory cortex. Neurosci Lett. 1993;157:162–166. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90727-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima N, Shirao T, Obata K. Molecular cloning of a developmentally regulated brain protein, chicken drebrin A and its expression by alternative splicing of the drebrin gene. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1993;19:101–114. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(93)90154-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadomrongkul V, Huerta PT, Shirao T, Aoki C. Stability of the distribution of spines containing drebrin A in the sensory cortex layer I of mice expressing mutated APP and PS1 genes. Brain Res. 2005;1064:66–74. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki M, Honkura N, Ellis-Davies GC, Kasai H. Structural basis of long-term potentiation in single dendritic spines. Nature. 2004;429:761–766. doi: 10.1038/nature02617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matus A. Actin-based plasticity in dendritic spines. Science. 2000;290:754–758. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5492.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Zhang Y, Tregoubov V, Janus C, Cruz L, Jackson M, Lu WY, MacDonald JF, Wang JY, Falls DL, Jia Z. Abnormal spine morphology and enhanced LTP in LIMK-1 knockout mice. Neuron. 2002;35:121–133. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizui T, Takahashi H, Sekino Y, Shirao T. Overexpression of drebrin A in immature neurons induces the accumulation of F-actin and PSD-95 into dendritic filopodia, and the formation of large abnormal protrusions. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;30:630–638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller D. Ultrastructural plasticity of excitatory synapses. Rev Neurosci. 1997;8:77–93. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.1997.8.2.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peitsch WK, Grund C, Kuhn C, Schnolzer M, Spring H, Schmelz M, Franke WW. Drebrin is a widespread actin-associating protein enriched at junctional plaques, defining a specific microfilament anchorage system in polar epithelial cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1999;78:767–778. doi: 10.1016/S0171-9335(99)80027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phend KD, Rustioni A, Weinberg RJ. An osmium-free method of epon embedment that preserves both ultrastructure and antigenicity for post-embedding immunocytochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem. 1995;43:283–292. doi: 10.1177/43.3.7532656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao A, Craig AM. Activity regulates the synaptic localization of the NMDA receptor in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 1997;19:801–812. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80962-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki Y, Hayashi K, Shirao T, Ishikawa R, Kohama K. Inhibition by drebrin of the actin-bundling activity of brain fascin, a protein localized in filopodia of growth cones. J Neurochem. 1996;66:980–988. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.66030980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekino Y, Tanaka S, Hanamura K, Yamazaki H, Sasagawa Y, Xue Y, Hayashi K, Shirao T. Activation of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor induces a shift of drebrin distribution: disappearance from dendritic spines and appearance in dendritic shafts. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:493–504. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shim KS, Lubec G. Drebrin, a dendritic spine protein, is manifold decreased in brains of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and Down syndrome. Neurosci Lett. 2002;324:209–212. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00210-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirao T, Obata K. Immunochemical homology of 3 developmentally regulated brain proteins and their developmental change in neuronal distribution. Brain Res. 1986;394:233–244. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(86)90099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirao T, Inoue HK, Kano Y, Obata K. Localization of a developmentally regulated neuron-specific protein S54 in dendrites as revealed by immunoelectron microscopy. Brain Res. 1987;413:374–378. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirao T, Kojima N, Nabeta Y, Obata K. Two forms of drebrins, developmentally regulated brain proteins, in rat. Proc Jpn Acad. 1989;65:169–172. [Google Scholar]

- Shirao T, Kojima N, Terada S, Obata K. Expression of three drebrin isoforms in the developing nervous system. Neurosci Res Suppl. 1990;13:S106–S111. doi: 10.1016/0921-8696(90)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Ito J, Takagi H, Saitoh F, Nawa H, Shimizu H. Biochemical evidence for localization of AMPA-type glutamate receptor subunits in the dendritic raft. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2001;89:20–28. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00051-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Sekino Y, Tanaka S, Mizui T, Kishi S, Shirao T. Drebrin-dependent actin clustering in dendritic filopodia governs synaptic targeting of postsynaptic density-95 and dendritic spine morphogenesis. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6586–6595. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-16-06586.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Mizui T, Shirao T. Down-regulation of drebrin A expression suppresses synaptic targeting of NMDA receptors in developing hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem. 2006;97(Suppl 1):110–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03536.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toni N, Buchs PA, Nikonenko I, Povilaitite P, Parisi L, Muller D. Remodeling of synaptic membranes after induction of long-term potentiation. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6245–6251. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-16-06245.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trommald M, Hulleberg G. Dimensions and density of dendritic spines from rat dentate granule cells based on reconstructions from serial electron micrographs. J Comp Neurol. 1997;377:15–28. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970106)377:1<15::aid-cne3>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez LE, Chen HJ, Sokolova I, Knuesel I, Kennedy MB. SynGAP regulates spine formation. J Neurosci. 2004;24:8862–8872. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3213-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villasana LE, Klann E, Tejada-Simon MV. Rapid isolation of synaptoneurosomes and postsynaptic densities from adult mouse hippocampus. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;158:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wouterlood FG, Jorritsma-Byham B. The anterograde neuroanatomical tracer biotinylated dextranamine: comparison with the tracer Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin in preparations for electron microscopy. J Neurosci Methods. 1993;48:75–87. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(05)80009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Ma QL, Calon F, Harris-White ME, Yang F, Lim GP, Morihara T, Ubeda OJ, Ambegaokar S, Hansen JE, Weisbart RH, Teter B, Frautschy SA, Cole GM. Role of p21-activated kinase pathway defects in the cognitive deficits of Alzheimer disease. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:234–242. doi: 10.1038/nn1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]