Abstract

There is considerable evidence of circadian rhythm abnormalities in mood disorders. Morningness-eveningness, the degree to which people prefer organizing their activity and sleep patterns toward the morning or evening, is related to circadian phase and is associated with mood, with relatively greater psychological distress among evening types. Given that circadian rhythms may also relate to the Behavioral Activation System (BAS) and positive affect (PA), but not to the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) or negative affect (NA), it was hypothesized that individual differences in BAS sensitivity and levels of PA, but not BIS and NA, would explain the association between morningness-eveningness and depression in a sample of 208 individuals with a range of depressive symptomatology. As predicted, increasing eveningness was associated with greater depression, lower BAS, and lower PA, but not directly associated with NA. Path analyses supported a model wherein morningness-eveningness is associated with depression via multi-step indirect paths including BAS reward responsiveness, PA, and NA. A path between BIS and depression was distinct from the one involving morningness-eveningness. A variety of alternative path models all provided a weaker fit to the data. Thus, results were consistent with the BAS and PA mediating the effects of morningness-eveningness on depression.

Keywords: circadian rhythms, mood, motivation, mood disorders

1. Introduction

More than three decades of research provide compelling evidence of circadian rhythm abnormalities in mood disorders (e.g., Wirz-Justice, 2005). Researchers have advanced a number of hypotheses attempting to relate the circadian abnormality to the other symptoms, including the ‘phase advance hypothesis’ (early morning awakenings and reduced REM latencies are due to short circadian periods), the ‘blunting hypothesis’ (reduced amplitudes in a number of circadian rhythms during the depressed phase that normalize upon remission), and the phase-shift hypothesis (PSH; delayed rhythms during winter for individuals with Seasonal Affective Disorder) among others. Although none of these have garnered unequivocal empirical support, tantalizing hints at the circadian-mood disorder link continue to emerge, ranging from the antidepressant effects of circadian-based treatments (e.g., bright light therapy) to preliminary evidence of polymorphisms in genes that influence the circadian cycle in patients with bipolar disorder (Mansour et al., 2005a).

An individual difference in circadian rhythms that is potentially important to understanding mood disorders is the degree to which individuals prefer organizing their activities closer to the morning or evening. Based on diurnal preference, or morningness-eveningness, people can be divided into chronotypes (i.e., “larks” and “owls”) with demonstrated differences in sleep-wake patterns and a variety of circadian rhythms, behavioral rhythms such as performance and exercise, and diurnal variation of mood (Kerkhof, 1998). Morningness refers to those who show extreme preferences for daytime activity; in these individuals, peak performance and alertness is associated with the early-morning hours. The opposite is true for those who show eveningness, or extreme preferences for nighttime activities; in these individuals, heightened alertness and peak performance is linked to the evening hours. Chronotypes also appear to differ in less intuitive areas such as personality (e.g., Larsen, 1985), school achievement (Giannotti et al., 2002), general health (Paine et al., 2006), and lifestyle regularity (Monk et al., 2004). Diurnal preference is typically assessed via subjective self-report questionnaires. These measures, which all provide a score that can be left as a continuous scale or assigned to a category (e.g., Definite Evening-type, Intermediate type, etc.) show moderate-to-large correlations with circadian phase using well-validated physiological markers such as melatonin and core body temperature (Bernert et al., 2006). Consequently, some studies have used self-reported morningness-eveningness as a proxy for circadian phase (e.g., Murray et al., 2005). Based on the original Horne and Ostberg (1976) scoring criteria, epidemiological studies indicate that 50–60 % of the population are morning-types, 2–6% of are evening-types1, and the rest fall in between these two extremes (Taillard et al., 2004, Paine et al., 2006). Also, morningness appears to increase with age (e.g, (Paine et al., 2006, Monk and Kupfer, 2007))

Despite demonstrations of the relationship between diurnal preference and physiological, behavioral, and psychological processes, few studies have looked directly at the association between diurnal preference and mood disorders. Drennan and colleagues (1991) investigated differences in Horne-Östberg morningness-eveningness scores between depressed (per DSM-IIIR criteria) outpatients and age- and sex-matched healthy controls. They found a significantly lower mean score (greater eveningness) in the depressed sample compared to the controls. Building on this work, Chelminski and colleagues (1999) examined diurnal preference and psychometrically-defined “depressiveness” in a large sample of college students. They defined “depressiveness” as scoring in the depressed range of at least two out of three depression scales (Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); Geriatric Depression Scale—Short Form (GDS-SF); and the Center for Studies Depression Scale (CESD)). Using this criterion, they found significant negative correlations (r ≈ −0.18) between the Horne-Östberg questionnaire and responses on all three depression measures (i.e., greater eveningness was related to greater depression) and a significantly higher incidence of evening-types among the “depressive” students.

The mechanisms underlying the association between eveningness and depression remain unknown. The circadian literature has generally focused on physiological or strictly chronobiological mechanisms in attempting to explain the link between mood disorders and circadian abnormalities, thereby neglecting some of the promising ideas to emerge from psychological literature. For example, Watson and colleagues have argued that the absence of positive affect (PA) is relatively specific to depression, thus distinguishing it from anxiety, which shares depression’s characteristically high negative affect (NA; reviewed in Watson, 2000). Other formulations suggest that depression involves both an underactive Behavioral Activation System (BAS; also referred to as a Behavioral Approach System or Behavioral Facilitation System), leading to diminished appetitive motivation and decreased PA, and a hyperactive Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS), resulting in increased NA (Fowles, 1994). Integrating the circadian and psychological literatures has the potential to elucidate the connection between chronobiological factors and mood dysregulation. Furthermore, accumulating evidence suggests that PA varies according to a circadian rhythm, but that NA fails to show a systematic daily variation (Clark et al., 1989, Thayer, 1989, Wood and Magnello, 1992, Murray et al., 2002, Hasler et al., 2007). Watson (2000) proposed that the circadian PA variation is a manifestation of activity in the underlying BAS, which promotes engagement with the environment during optimal times for reward (i.e., daytime). In contrast to asserting an adaptive basis for the circadian control of appetitive motivation and PA, the model posits that NA lacks systematic circadian variation because it is the manifestation of a reactive BIS responding to aversive or ambiguous stimuli. Thus, systematic variations in BAS may have adaptive functions in terms of motivating organisms toward goal-seeking activities at optimal times, whereas an endogenous variation in BIS would not clearly be adaptive.

The present study attempted to integrate these previous findings and theoretical models by examining the association among diurnal preference, motivational systems (BAS and BIS), and affect (PA and NA) in an adult sample with a wide range of depressive symptoms. It was hypothesized that diurnal preference (as a proxy for circadian phase) would be related to BAS sensitivity and PA, but not to BIS sensitivity or NA. It also was predicted that greater eveningness would be associated with lower BAS sensitivity and lower levels of PA. Finally, this work investigated whether BAS sensitivity and PA would statistically explain the relationship between diurnal preference and severity of depressive symptoms.

2. Methods

2.1. Procedure and participants

Two hundred and eight participants (140 females; mean age=19.23 years, range=17 to 33) were drawn from a larger study investigating risk factors for depression. Participants were sampled to represent a broad range of depressive symptoms, from virtually no depressive symptoms to warranting a past or current DSM-IV diagnosis of major depressive disorder (MDD; 106 participants with no past or current MDD or dysthymia, 52 with only past MDD, 6 with only current dysthymia, and 44 with current MDD). Exclusion criteria included current antidepressant pharmacological treatment, comorbidity or conditions that would suggest that the presenting symptoms may be something other than a Major Depressive Episode (any current Axis I disorder other than depression; endocrinological or neurological disorders; any history of psychotic disorders, psychotic symptoms, or mania; and substance abuse or dependence within the past 4 months); current active suicidal potential necessitating immediate treatment. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the University of Arizona prior to recruitment.

An intake interview session was administered by a post-masters-level clinician to (1) confirm the absence of exclusionary factors and (2) assess depression using the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (First et al., 2002) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Hamilton, 1967). In ongoing research across a variety of studies, raters trained by the second author (J.J.B.A.) have obtained inter-rater reliabilities for depression diagnoses utilizing the SCID that meet or exceed 0.90, and for depression severity using the HRSD that exceed .95.

2.2. Measures

Eligible subjects – both depressed and nondepressed –completed a variety of questionnaires assessing individual differences in mood and motivation, including the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, General Version (PANAS-general; Watson et al., 1988), the Behavioral Inhibition and Behavioral Activation Scales (BIS/BAS, Carver and White, 1994), and the Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd Edition (Beck et al., 1996). To examine sleep and circadian factors in association with depression, participants also completed the Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (Horne and Östberg, 1976), which is a 19-item self-report scale with questions focusing on habitual waking and bed times, preferred times of physical and mental performance, and subjective alertness upon awakening and prior to initiating sleep. The MEQ yields a total score ranging from 16 to 86 on a morningness-eveningness continuum, with lower scores reflecting less morningness.

2.3. Data analysis

Data analyses proceeded in three steps. First, the association between morning-eveningness, mood symptoms, and motivation was assessed via Pearson correlations, and mean differences were evaluated via a series of one-way ANOVAs. Second, a series of meditational analyses were conducted following the steps outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986), which is a commonly used approach for determining the extent to which any given bivariate association can be statistically explained by another variable. The steps for this analysis are described below just before they are reported. Finally, to examine the possibility that multiple variables explain the association between morning-eveningness and depression, a series of path models were fit to the observed data. As described below, the logic of path analysis involves estimating a series of conceptually related nested models (Bentler and Bonnet, 1980). If setting an estimated parameter to zero does not lead to a significant deterioration of the model’s fit to the observed data (as indexed by a non-significant change in the model χ2), the more parsimonious model is retained as a better characterization of the variance-covariance matrix.

3. Results

Following the presentation of the relationship between morningness-eveningness and depression severity, analyses designed to test the potential mediating role of mood and motivation are presented. Age was assessed as a potential covariate, but was found unrelated to MEQ scores and to BDI-II scores, and thus all results are unadjusted for age; all major findings remain the same if age-adjusted scores are utilized. In order to account for potential circadian rhythm effects, time-of-day of assessment (M=14:47, range=9:32 to 20:46) also was assessed as a potential covariate, but was unrelated to any of the variables of interest, with no impact on major findings.

3.1 Morningness-eveningness, mood, and motivation

Pearson correlations between all relevant variables are displayed in Table 1. Eveningness (lower morningness-eveningness scores) was significantly associated with higher depression scores (as predicted) as measured by the BDI-II. This association, however, was not significant using the HRSD (in contrast to predictions). With respect to other measures, greater morningness was associated with higher BAS sensitivity on both BAS Total and one subscale (BAS-Reward Responsiveness) showed a trend towards statistical significance with another subscale (BAS-Drive), and was significantly associated with higher PA. In contrast, morningness-eveningness was not significantly related to BIS sensitivity or mean NA.

Table 1.

Correlations between Morningness-Eveningness Scores and Mood and Motivation Measures

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Morningness-eveningness, MEQ | — | |||||||||

| 2. Mean Depression, BDI-II | −.22** | — | ||||||||

| 3. Depression, HRSD | −.07 | .74*** | — | |||||||

| 4. Mean BAS Total | .14* | −.51*** | −.44*** | — | ||||||

| 5. Mean BAS-Reward Responsiveness | .23*** | −.45*** | −.41*** | .78*** | — | |||||

| 6. Mean BAS-Drive | .12† | −.40*** | −.31*** | .84*** | .50*** | — | ||||

| 7. Mean BAS-Fun Seeking | −.01 | −.40*** | −.34*** | .81*** | .53*** | .53*** | — | |||

| 8. Mean BIS | −.00 | .49*** | .49 | −.12 | −.09 | −.05 | −.15* | — | ||

| 9. Mean PA, from PANAS | .24*** | −.66*** | −.52*** | .64*** | .61*** | .45*** | .50*** | −.35*** | — | |

| 10. Mean NA, from PANAS | −.11 | .75*** | .61 | −.31*** | −.28*** | −.26** | −.22** | .53*** | −.43*** | — |

Note: Lower MEQ scores denote lower morningness (greater eveningness);

= p<.05;

= p<.01

= p<.001; n=208

A one-way ANOVA was employed to evaluate differences in eveningness in relation to clinical levels of depression. The omnibus test revealed that there was no significant difference (p =0.19) between those with no history of meeting MDD criteria (never depressed), those with no history of meeting MDD criteria but currently meeting dysthymia criteria (currently dysthymic), those previously but not currently meeting MDD criteria (previously depressed), and those currently meeting MDD criteria (currently depressed). Based on the hypothesis that the association between morningness-eveningness and depression occurs at a trait-level, an exploratory two-tailed t-test was employed to compare the individuals in never depressed group with those ever experiencing depression or dysthymia (the remaining three groups combined). This test revealed that, on average, those never experiencing depression or dysthmia had significantly (t(206)=2.19, p=0.03) higher MEQ scores (greater morningness).

3.2 Mediation analyses

Following Baron and Kenny (1986), the first step of testing for mediation is establishing a significant association between the independent and dependent variables; that is, morningness-eveningness and depression severity as based on mean BDI score (r= −0.22, p=0.002). The next step is to establish significant relationships between the independent variables and any putative mediators. According to Watson’s model, PA and BAS sensitivity should act as the mediators in this relationship. The BAS-Reward Responsiveness (BAS-RR) was selected as the BAS subscale of choice for this analysis based on three considerations: 1) Carver’s (2004) recommendation to use the individual BAS subscales instead of the total BAS score; 2) theoretical considerations (approach-related tendencies as related to reward responsivity (e.g., Pizzagalli et al., 2005), and 3) the fact that it was the BAS subscale with the highest correlation with MEQ (see Table 1),

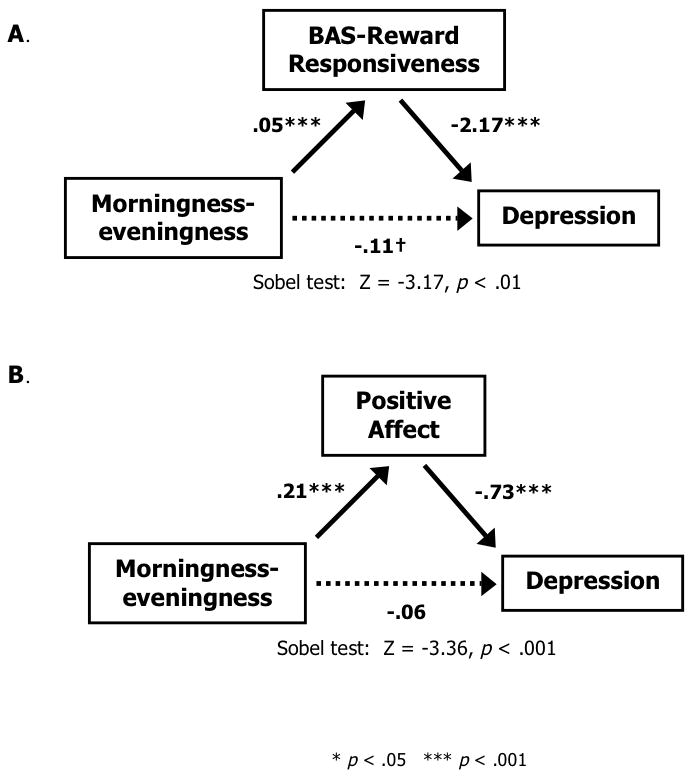

In order to achieve full mediation, inclusion of the mediator in the model should reduce the association between the independent and dependent variables to zero, whereas partial mediation would occur when this association was reduced to some nonzero value. Analysis of the mediational role of BAS-RR revealed that the effect of morningness-eveningness (B=−0.22, p=0.001) still had a trend towards significance (B=−0.11, p=0.08) when BAS-RR (B=−0.47, p<0.001) was entered into the regression equation (see Figure 1A). The Sobel test indicated that the mediation effect was significant (Z=−3.17, p=0.002). Therefore, as hypothesized, BAS-RR partially mediated the association between morningness-eveningness and depression. In contrast, analyses supported PA as a full mediator of the association between morningness-eveningness and depression (see Figure 1B). The effect of morningness-eveningness was no longer significant (B=−0.06, p>0.05) when PA (B=−0.64, p<0.001) was entered into the regression equation, and the Sobel test indicated that the mediation effect was significant (Z=−3.36, p<0.001).

Figure 1.

BAS-Reward Responsiveness (Panel A), and Positive Affect (Panel B) both partially (A) or fully (B) mediate the association between morningness-eveningness and depression severity (BDI-II scores). The parenthetical path coefficients indicate the direct effect of MEQ on depression after taking the mediator into account.

In an attempt to ascertain the direction of causality, mediational analyses were also performed in the reverse direction, switching the independent and dependent variables, testing whether BAS-RR or PA mediated the association between depression and morningness-eveningness. Sobel tests indicated that none of these indirect effects were significant, suggesting that morningness-eveningness influences depression rather than the reverse (i.e., depression influencing morningness-eveningness). These models were further explored by switching the putative mediator with the dependent variables (i.e., BDI score as the mediator, BAS-Responsiveness and PA as the dependent variables) as previously recommended (Sheets and Braver, 1999). Both of these models indicated that BDI mediated the associations between morningness-eveningness and BAS-Responsiveness or PA, thus leaving the direction of causality between BAS-RR, PA, and BDI an open question.

3.3 Path analyses

Because the standard Baron and Kenny (1986) mediation analyses do not permit evaluation of a model containing two mediators in sequence, path analyses were used to test the hypothesis that morningness-eveningness affects depressive symptomatology indirectly through BAS-RR and PA (rather than through BIS sensitivity and NA) when all four of the variables are included in the model simultaneously. The path models were specified using MPlus Version 4.0 (Muthén and Muthén, 2006) using full maximum likelihood (ML) estimation. Data were complete for 99.4% of the participants; the models were estimated with all available data under missing completely at random assumptions without any form of imputation. Several fit indices were used to evaluate how well the model specifications characterized the observed data. Hu and Bentler (1999) suggest using a combination of the ML-based standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR) supplemented with the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) or root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) to assess model fit; because RMSEA tends to overreject the population model at small sample sizes, both RMSEA and CFI were included in the current study. SRMR values < 0.08, CFI values > 0.95, and RMSEA values of < 0.06 suggest a relatively good fit of the model to the observed data.

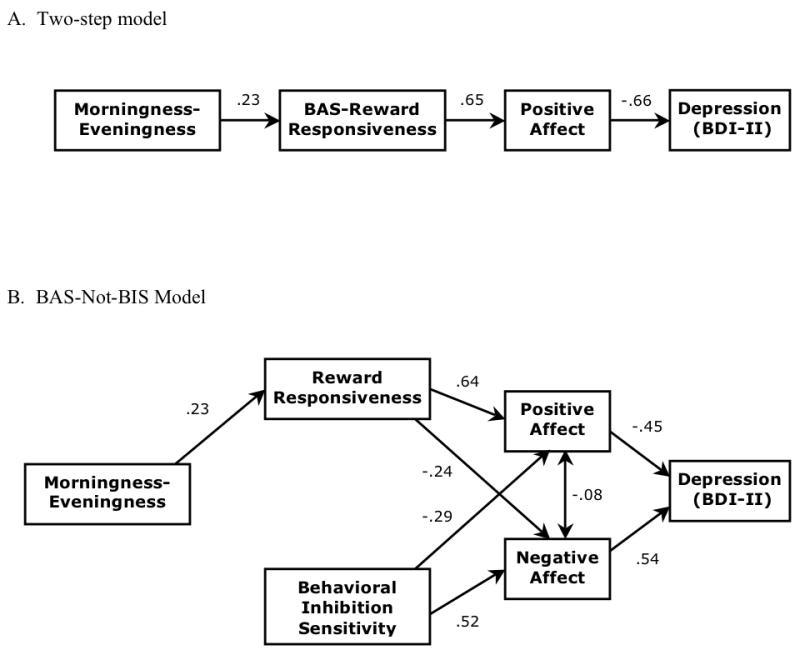

Based on the original hypothesis that the association between morningness-eveningness and depression would be mediated through reward responsiveness and PA, a series of increasingly complex models were evaluated, beginning with a two-step mediation process. According to the two-step model, individuals reporting higher levels of eveningness will report less reward responsiveness, which will be associated with lower levels of PA, which in turn will be associated with more depressive symptomatology. Consistent with reward responsiveness and PA mediating the association between morningness-eveningness and depression, the direct path from morningness-eveningness to depression was predicted to be non-significant in the presence of the two mediators. This two-step model is displayed in Figure 2a.

Figure 2.

In order to explain the association between morningness-eveningness and depression, the primary path models under consideration include a two-step mediation model (Panel A) running sequentially through BAS-Reward Responsiveness and Positive Affect, and full a BAS-Not-BIS model (Panel B) that includes a separate path starting with BIS sensitivity as an additional exogenous variable.

Although the predictions for the two-step model held, the overall fit to the data was less than ideal RMSEA=0.08, see Table 2, and a variety of alternative models were investigated. First, the model was re-specified by allowing morningness-eveningness to load directly onto positive affect. According to this tentative model, two mediation processes are operating: the original two-step process (MEQ→BAS-RR→PA→BDI), and a single-step process from MEQ through PA along to BDI scores. While including the MEQ-PA path led to improved fit indices (e.g., RMSEA=0.06) relative to the original two-step model (which is nested under the revised specification), the path showed only a trend towards significance (p=0.07). Furthermore, fixing the estimate from MEQ to PA to zero leads to a non-significant degradation in model fit (Δχ2(1)=3.27, p>0.05). Thus, the revised model is not a significant improvement beyond the original two-step model, and there is no support for the second mediation process (MEQ→PA→BDI). To address questions about the direction of causality, two alternative models were specified in which BDI became the putative mediator (MEQ→BDI→RR→PA and MEQ→RR→BDI→PA). The fit of these two models was poor (e.g., CFI ≤ 0.75), diminishing the likelihood of depression mediating the association between morningness-eveningness and reward responsiveness and/or PA.

Table 2.

Summary of fit indices for path models

| Model | χ2 | p-value | df | Parametersa | CFI | SRMR | RMSEA (90% C.I.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-step | 6.80 | .08 | 3 | 7 | .98 | .05 | .08 (.00, .16) |

| BAS-Not-BIS | 11.51 | .12 | 7 | 14 | .99 | .05 | .06 (.00, .11) |

CFI, Comparative Fit Index; SRMR, ML-based standardized root mean squared residual; RMSEA, root mean squared error of approximation.

Note: The Two-step model includes MEQ, BAS-RR, PA, and BDI. The BAS-Not-BIS model includes MEQ, BAS-RR, PA, BIS, NA, and BDI,

In an effort to improve on the relatively poor fit of the two-step model while including consideration of alternative mechanisms explaining the association between morningness-eveningness and depression, the model was broadened to investigate the possible role of BIS and NA. According to the theory behind these analyses, which can be called the BAS-Not-BIS model, the association between morningness-eveningness and depression should operate through BAS-RR, rather than BIS levels. Although a priori hypotheses predicted that NA would not play a role in this association, based on the substantial zero-order correlations between it and BAS-RR, NA was included in the model (although with no direct path from MEQ was estimated). 2 Specifically, individuals reporting higher levels of eveningness should report less reward responsiveness and lower levels of PA, as well as higher levels of NA and more depressive symptomatology. At the same time, it is possible for BIS sensitivity (as an additional exogenous variable) to be associated with depressive symptomatology through NA. As shown in Table 2, the BAS-Not-BIS specification provided a reasonable fit to the observed data. A critical test of the BAS-Not-BIS model is the direct path from morningness-eveningness to BIS sensitivity. Removing this path from the model without significantly degrading the fit suggests that BIS sensitivity does not account for the association between morningness-eveningness and affect. Consistent with predictions, there was no significant association between MEQ and BIS, and removing this effect from the model did not worsen the overall model fit (Δχ2(1) =0.02, p=0.91), lending further provisional support to the BAS-Not-BIS model.

Finally, the fit of several alternative specifications were assessed to determine whether they could better explain covariation among the observed variables. First, an alternative specification that reversed every arrow in Figure 2b was tested. This specification, with BDI as an exogenous variable and with both MEQ and BIS sensitivity as endogenous variables, provided a relatively weak fit to the data (Δχ2(8)=26.42, p<0.001, CFI=0.96. RMSEA=0.11 (90% CI, 0.06–0.15), SRMSR=0.06). In the next model, the regressions from BIS to PA and from BAS-RR to NA were eliminated, and PA and NA were allowed to covary freely. This model suggests that the covariation of NA and PA is more state-like, without the cross-valenced association with BAS-RR and BIS levels, respectively. This model also provided a poor fit to the data (Δχ2(9)=59.66, p<0.001, CFI=0.89, RMSEA=0.16 (90% CI, 0.13–0.21), SRMSR=0.15), which suggests that these negative cross-valenced regressions are an important feature of the model; in the present data, NA is associated high levels of BIS as well as low levels of BAS-RR, and, similarly, PA is associated with high levels of BAS-RR as well as low levels of BIS. Finally, a model was tested that treated BIS and BAS-RR as the exogenous variables, both of which were freely associated with MEQ and PA and NA, respectively. In this model, the cross-valenced influence of BAS-RR on NA operates through MEQ, and the cross-valenced influence of BIS on PA operates through MEQ. PA and NA were allowed to covary freely. MEQ was specified to predict BDI directly, as well as both PA and NA; PA and NA, in turn, also predicted BDI scores. As with the other specifications, this model also provided a weak fit to the data (Δχ2(5)=51.52, p<0.001, CFI=0.90, RMSEA=0.21 (90% CI, 0.16–0.33), SRMSR=0.14), indicating that the effect of trait-level approach/avoidance motivations on depression does not operation through MEQ. In summary, the final model (Figure 2b) is consistent with two paths predicting depression symptom severity. In the first path, reward responsiveness, PA, and NA mediate the association between morningness-eveningness and depression, while in the second path, PA and NA mediate the association between BIS sensitivity and depression, and there is no effect from morningness-eveningness to BIS levels.

4. Discussion

The findings reported here replicate an association between morningness-eveningness and depression and lend further credence to a potentially important link between diurnal preference and mood dysregulation. The differences in morningness-eveningness based on diagnostic category further suggest that the association with depression may be at the trait-level, with greater eveningness promoting lowered mood. Furthermore, the findings highlight one possible mechanism for this link between eveningness and depression (via the appetitive motivational system) while casting doubt on another (via behavioral inhibition). The findings also converge with past research on the Behavioral Activation System and depression, and may serve to bridge the two literatures. A close association between the Behavioral Inhibition System and depression exists, but this process operates in a distinct pathway from the one involving morningness-eveningness. Finally, analyses support a mediating role of both PA and NA in each of these two pathways.

These data add to a growing literature demonstrating an association between morningness-eveningness and mood dysregulation. Other studies have looked indirectly at these associations, but nearly all are consistent in finding greater psychological distress associated with greater eveningness3. Moreover, much of the work was conducted in international samples, indicating cross-cultural generalizeability of the phenomenon. Examining an Italian adolescent sample, Giannotti and colleagues (2002) reported that an evening preference predicted poorer emotional adjustment (i.e., greater anxiety and depressed mood) even after accounting for the variation associated with demographics (i.e., age, sex, socioeconomic status, and pubertal development), sleep variables (i.e., sleep length, sleep debt, and sleep/wake problems), and substance abuse. In addition to greater emotional distress, the authors indicated that evening-types reported greater substance use, apparently taken to promote sleep. More recently, Gau and Merkangas (2004) found that along with age, negative mood was associated with a tendency towards greater eveningness in Taiwanese adults. Notably, this association was greater among those with more irregular sleep schedules. Finally, Ong and colleagues (2007) found greater depressive symptomatology and more variable rising times among evening-types in a sample of individuals seeking treatment for insomnia, even after adjusting for insomnia severity, suggesting that this insomnia subgroup may be particularly sensitive to the effects of sleep disruption.

Several studies have provided evidence that this relationship may extend to individuals with bipolar disorder. Accounting for the influence of age, (Mansour et al., 2005b) found increased eveningness among Bipolar I patients relative to controls, and even greater eveningness among patients who experienced rapid mood swings relative to those who did not. At least two other studies (e.g., Ahn et al., 2008, Hatonen et al., 2008) have replicated this bipolar-eveningness association. Taken together with the current findings, these data suggest that diurnal preference is associated with mood regulation both within unipolar and bipolar depression.

4.1 Morningness-eveningness and motivational systems

For perhaps the first time among published studies, these data suggest that preferences in sleep timing are related to at least one manifestation of the appetitive motivational system, specifically responsiveness to rewards (and perhaps to a lesser degree, drive). While this association between a greater tendency towards eveningness and reduced reward responsiveness is consistent with the association between eveningness and depressive symptomatology (both via self-report and diagnostic category) demonstrated by these and prior data, it is more difficult to reconcile this association with the evidence for increased eveningness among individuals with Bipolar I disorder. Further complicating the picture is a recent finding that, among healthy working adults, sub-clinical manic-type symptoms were also associated with eveningness (Soehner et al., 2007). Perhaps eveningness is associated with dysregulation in the systems underlying PA and reward responsiveness rather than simply influencing the mean levels of these processes. In addition, it is uncertain why morningness-eveningness was unrelated to depressive symptomatology as measured by the HRSD, although the correlation between BDI scores and HRSD scores is far from unity (r=0.74 in this sample). Moreover, the HRSD scores include a variety of symptoms in addition to depression, including anxiety and somatization, and thus at low levels of HRSD severity scores may reflect a heterogeneous collection of minor symptoms that are not specific to depression; as a result, the HRSD may be less sensitive to the core construct of depression at lower scores.

The apparent lack of an association between morningness-eveningness and the Behavioral Inhibition System is consistent with predictions that circadian processes are not clearly implicated in the Behavioral Inhibition System (Watson, 2000). Likewise, although the apparent lack of diurnal rhythmicity in NA noted in previous studies would not necessarily preclude a direct association between morningness-eveningness and NA, the absence of such a (significant) correlation is further incremental evidence that circadian processes are less directly relevant to NA.

4.2 Potential mechanisms

Although these results are consistent with previous research and theory, the precise mechanism of action remains unknown. As noted above, Watson (2000) suggested that circadian processes underlie the BAS and subsequently PA, and, from this standpoint, it is arguable that greater eveningness is associated with disrupted circadian rhythms, which thereby disrupts the processes underlying PA. With this in mind, one possibility is that the patterns of PA (rather than merely the overall level) are different among individuals high in eveningness. Bailey and Heitkemper (2001) reported a nonsignificant trend towards blunting (reduced amplitude) in melatonin rhythms associated with eveningness. Likewise, depression is associated with blunting in a variety of circadian rhythms that normalize upon remission (Souetre et al., 1989). With respect to this study’s findings, blunting may occur in the PA rhythm and manifest as diminished peaks in motivation, activity, and experienced pleasure (akin to anhedonia). Still, in contrast to this perspective, Baehr and colleagues (2000) reported greater amplitudes in core body temperature rhythms among evening-types.

Another potential explanation for the association between morningness-eveningness, the appetitive motivational system, and depression derives from recent findings that clock genes are present in the mesolimbic dopamine system, the neural circuit mediating response to reward (Nestler and Carlezon, 2006). Although direct pathways to this system from the hypothalamic central pacemaker (i.e., the suprachiasmatic nucleus) have yet to be demonstrated, a compelling possibility exists that reward responsiveness is under circadian regulation. If true, changes in reward responsiveness associated with depression may be explained, in part, by the circadian alterations (e,g., longer circadian period, later circadian phase) inherent in greater eveningness (Duffy et al., 2001).

In addition to the possible involvement of the dopamine system, overlapping serotonergic pathways may underlie the association between morningness-eveningness and depression. DeYoung and colleagues (2007) found a link between morningness and a higher-order personality factor, Stability, representing emotional (reversed Neuroticism), social (Agreeableness), and motivational (Conscientiousness) domains. They assert this association lends credence to their hypothetical model that posits common serotonergic pathways between circadian rhythms and the neurophysiology of Stability. Indeed, serotonin is a major afferent pathway to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (Moore and Speh, 2004). Furthermore, and with relevance to the apparent role of PA, serotonergic function has been linked to the extent of PA (e.g., Williams et al., 2006).

Also relevant to the observed effects, diurnal preferences are linked to overall lifestyle patterns. Monk and colleagues (2004) demonstrated that lifestyle regularity (i.e., the uniformity of daily activities such as eating, exercise, and social rhythms) was decreased among evening compared to morning types. This effect is likely driven by the timing of sleep, which appears significantly more variable among evening types (Ishihara et al., 1987). In consideration of this research, a mismatch between circadian rhythms and sleep/wake schedules among evening types is associated with sleep restriction and unstable social rhythms, which may importantly influence affective lability. The unstable sleep and social rhythms observed among evening types may make affect regulation more difficult for evening types, presenting risk for depression and other affective disturbances.

4.3 Limitations and future directions

This study had a number of limitations. First and foremost, the absence of a longitudinal design precludes the demonstration of temporal precedence in the mediation analyses. It remains uncertain from these analyses, and past literature, whether morningness-eveningness is a predisposing, precipitating, or perpetuating factor for depression, or merely epiphenomenal to other depressive symptomatology; the greater degree of eveningness among both past and current sufferers of Major Depression, however, suggests that diurnal preference more likely acts in a predisposing or perpetuating manner. Second, the study design did not include measures necessary for winnowing the proposed mechanisms (e.g., sleep diaries to measure sleep variability or multiple daily assessments of PA to measure the amplitude of the PA rhythm). Future studies should address these possibilities. Third, significant effects in a reversed mediation model indicate that the temporal precedence of reward responsiveness, PA, and depression currently remains unknown, although the path analyses support a two-step process in which reward responsiveness and PA are mediating, in turn, the association between morningness-eveningness and depression. Another consideration that reinforces a necessary agnosticism about the direction of these effects is the possibility of a bi-directional association between morningness-eveningness and depression. The oft-noted improvement in mood towards the evening hours that is associated with depression could encourage or maintain a pattern of activity later in the day (Murray, Allen, and Trinder, 2003). Fourth, it is important to recognize that the final BAS-Not-BIS specification is just one of many alternative path models that would fit the data equally well (Tomarken and Waller, 2003). Importantly, the BAS-Not-BIS specification was derived from theory and three compelling alternative specifications were evaluated, none which did as good a job representing the covariation in the observed variables; evaluation of these alternative models bolsters confidence in the utility of the BAS-Not-BIS specification. Fifth, the BIS/BAS scales represent self-reported styles, and behavioral and/or psychophysiological assessments may provide a better assessment of these constructs.

Finally, given that diurnal preference is related to, but not synonymous with, circadian phase, it remains uncertain how integral circadian mechanisms are to the present findings. Even so, when considered in conjunction with other recent reports of a link between circadian processes and PA (Hasler et al., 2008), the observed effects underscore the value of continued research in this area. Further research should employ physiological measures of circadian rhythms (e.g., melatonin) that would allow precise determination of circadian phase as well as the more sophisticated circadian parameters (e.g., advanced mathematical models using a fundamental sinusoid plus higher-order harmonics, see Klerman and Hilaire (2007)) that may be necessary to fully elucidate the mood-circadian linkage.

4.4 Conclusion

The findings reported in this study identify multiple explanatory pathways in the associations between diurnal preference and mood disturbance. Notably, the results support a mediating role for BAS and PA in a model with eveningness predicting greater depressive symptom severity. This is the first investigation to test the directionality of effects between morningingess-eveningness, PA, and a BIS-BAS model, particularly using a confirmatory factor-analytic approach. To further examine causality, longitudinal studies will be necessary to replicate and build upon these preliminary findings. With regard to the clinical significance of the present study, these results may warrant further research specifically aimed at examining whether previously-established chronotherapeutic approaches (e.g., advancing the sleep-wake schedule; Wirz-Justice and Van den Hoofdakker, 1999) show benefits (with unique effects on PA) for evening types with depressive symptomatology. Likewise, although further research using physiological measures is necessary, by implicating reward processes the findings point towards a potentially fruitful direction for the development of novel pharmacological interventions. For example, medications that selectively target the mesolimbic dopamine system might be particularly beneficial for depressed evening types. Finally, given the apparent interaction of circadian and reward processes, one might speculate that social rhythm therapy (Frank, 2007) might be a useful approach to reducing depression in evening types by encouraging stable daily rhythms of sleep and positive reinforcement.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01- MH066902 to J.J.B.A. The authors wish to thank Jamie Velo, Eliza Ferguson, Dara Halpern, and Jim Coan for assistance with various aspects of the project essential to being able to collect and analyze these data.

Footnotes

Given that the original scoring criteria were established using a student sample, Taillard and colleagues (2004) have recommended consideration of their revised scoring criteria based on a working middle-aged sample. Studies using these criteria report relatively equivalent proportions of morning- and evening-types (approximately 25% each) (Paine et al., 2006; Taillard et al., 2004).

Based on the substantial zero-order negative correlation (r=−0.43, p<0.001) between PA and NA, we also added a reciprocal pathway between them. This path was small but significant (r=−0.08, p<0.05), and it also significantly improved the fit of the model compared to a BAS-Not-BIS model without this pathway (Δχ2(21)=3.84, p=0.05).

One large survey study (n=1229) did not find any “socioeconomic, cognitive, or health disadvantage” for evening-types (Gale and Martyn, 1998). However, the study based diurnal preference on a couple of survey items rather than an established instrument, and the study did not assess affective dimensions of functioning.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ahn YM, Chang J, Joo YH, Kim SC, Lee KY, Kim YS. Chronotype distribution in bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia in a Korean sample. Bipolar Disorders. 2008;10:271–275. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baehr EK, Revelle W, Eastman CI. Individual differences in the phase and amplitude of the human circadian temperature rhythm: with an emphasis on morningness–eveningness. Journal of Sleep Research. 2000;9:117–127. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey SL, Heitkemper MM. Circadian rhythmicity of cortisol and body temperature: morningness-eveningness effects. Chronobiology International. 2001;18:249–261. doi: 10.1081/cbi-100103189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory manual. Harcourt, Brace; Boston: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Bonnett DG. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Bernert RA, Hasler BP, Cromer KR, Joiner TE., Jr Diurnal preferences and circadian phase: A meta-analysis. Sleep. 2006;29:A54–55. [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67:319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Chelminski I, Ferraro F, Petros T, Plaud J. An analysis of the “eveningness-morningness” dimension in “depressive” college students. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1999;52:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D, Leeka J. Diurnal variation in the positive affects. Motivation and Emotion. 1989;13:205–234. [Google Scholar]

- Deyoung CG, Hasher L, Djikic M, Criger B, Peterson JB. Morning people are stable people: Circadian rhythm and the higher-order factors of the Big Five Personality and Indvidual Differences. 2007;43:267–276. [Google Scholar]

- Drennan M, Klauber M, Kripke D, Goyette L. The effects of depression and age on the Horne-Ostberg morningness-eveningness score. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1991;23:93–98. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90096-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy JF, Rimmer DW, Czeisler CA. Association of intrinsic circadian period with morningness-eveningness, usual wake time, and circadian phase. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2001;115:895–599. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.115.4.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RC, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I),. Biometrics Research. New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC. A motivational theory of psychopathology. In: Spaulding W, editor. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation: Integrated views of motivation and emotion. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln, Nebraska: 1994. pp. 181–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank E. Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy: A means of improving depression and preventing relapse in bipolar disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;63:463–473. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SSF, Merikangas KR. Similarities and differences in sleep-wake patterns among adults and their children. Sleep. 2004;27:299–304. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.2.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannotti F, Cortesi F, Sebastiani T, Ottaviano S. Circadian preference, sleep and daytime behaviour in adolescence. Journal of Sleep Research. 2002;11:191–199. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2002.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. The British journal of social and clinical psychology. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasler BP, Mehl MR, Bootzin RR, Vazire S. Social behaviors associated with positive but not negative affect show evidence of circadian regulation. 2007 Manuscript under editorial review. [Google Scholar]

- Hasler BP, Mehl MR, Bootzin RR, Vazire S. Preliminary evidence of diurnal rhythms in everyday behaviors associated with positive affect. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008;42:1537–1546. [Google Scholar]

- Hatonen T, Forsblom S, Kieseppa T, Lonnqvist J, Partonen T. Circadian Phenotype in Patients with the Co-Morbid Alcohol Use and Bipolar Disorders. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:564–568. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne JA, Östberg O. A self-assesment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness. International Journal of Chronobiology. 1976;4:97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara K, Miyasita A, Inugami M, Fukuda K, Miyata Y. Differences in sleep-wake habits and EEG sleep variables between active morning and evening subjects. Sleep. 1987;10:330–342. doi: 10.1093/sleep/10.4.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerkhof GA. The 24-hour variation of mood differs between morning- and evening-type individuals. Perceptual & Motor Skills. 1998;86:264–266. doi: 10.2466/pms.1998.86.1.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klerman EB, Hilaire MS. On mathematical modeling of circadian rhythms, performance, and alertness. J Biol Rhythms. 2007;22:91–102. doi: 10.1177/0748730407299200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen RJ. Individual differences in circadian activity rhythms and personality. Personality and Indvidual Differences. 1985;6:305–311. [Google Scholar]

- Mansour HA, Monk TH, Nimgaonkar VL. Circadian genes and bipolar disorder. Annals of Medicine. 2005a;37:196–205. doi: 10.1080/07853890510007377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour HA, Wood J, Chowdari KV, Dayal M, Thase ME, Kupfer DJ, Monk TH, Devlin B, Nimgaonkar VL. Circadian phase variation in Bipolar I disorder. Chronobiology International. 2005b;22:571–584. doi: 10.1081/CBI-200062413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk TH, Buysse DJ, Potts JM, Degrazia JM, Kupfer DJ. Morningness-eveningness and lifestyle regularity. Chronobiology International. 2004;21:435–443. doi: 10.1081/cbi-120038614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk TH, Kupfer DJ. Which Aspects of Morningness-Eveningness Change with Age? Journal of Biological Rhythms. 2007;22:278. doi: 10.1177/0748730407301054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RY, Speh JC. Serotonin innervation of the primate suprachiasmatic nucleus. Brain Res. 2004;1010:169–73. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray G, Allen NB, Trinder J. Mood and the circadian system: Investigation of a circadian component in positive affect. Chronobiology International. 2002;19:1151–1169. doi: 10.1081/cbi-120015956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray G, Michalak EE, Levitt AJ, Levitan RD, Enns MW, Morehouse R, Lam RW. O sweet spot where art thou? Light treatment of Seasonal Affective Disorder and the circadian time of sleep. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2005;90:227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus version 4.0. Muthén and Muthén; Los Angeles: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Carlezon J, William A. The mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit in depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2006;59:1151–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong JC, Huang JS, Kuo TF, Manber R. Characteristics of insomniacs with self-reported morning and evening chronotypes. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2007;3:289–294. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paine SJ, Gander PH, Travier N. The epidemiology of morningness/eveningness: Influence of age, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors in adults (30–49 years) Journal of Biological Rhythms. 2006;21:68–76. doi: 10.1177/0748730405283154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizzagalli DA, Sherwood RJ, Henriques JB, Davidson RJ. Frontal brain asymmetry and reward responsiveness. Psychological Science. 2005;16:805–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets VL, Braver SL. Organizational status and perceived sexual harassment: Detecting the mediators of a null effect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:1159–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Soehner AM, Kennedy KS, Monk TH. Personality Correlates with Sleep-Wake Variables. Chronobiology International. 2007;24:889–903. doi: 10.1080/07420520701648317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souetre E, Salvati E, Belugou JL, Pringuey D, Candito M, Krebs B, Ardisson JL, Darcourt G. Circadian rhythms in depression and recovery: evidence for blunted amplitude as the main chronobiological abnormality. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28:263–278. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taillard J, Philip P, Chastang JF, Bioulac B. Validation of Horne and Ostberg Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire in a Middle-Aged Population of French Workers. J Biol Rhythms. 2004;19:76–86. doi: 10.1177/0748730403259849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thayer RE. The biopsychology of mood and arousal. Oxford University Press; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Waller NG. Potential problems with ‘well fitting’ models. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:578–598. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D. Mood and Temperament. Guilford Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams E, Stewart-Knox B, Helander A, Mcconville C, Bradbury I, Rowland I. Associations between whole-blood serotonin and subjective mood in healthy male volunteers. Biol Psychol. 2006;71:171–4. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirz-Justice A. Chronobiological strategies for unmet needs in the treatment of depression. Medicographia. 2005;27:223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Wirz-Justice A, Van Den Hoofdakker RH. Sleep deprivation in depression: what do we know, where do we go? Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46:445–453. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00125-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood C, Magnello ME. Diurnal changes in perceptions of energy and mood. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 1992;85:191–194. doi: 10.1177/014107689208500404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]