Abstract

Background

To test the angiogenesis promoting effects of bone marrow cells when co-transplanted with islets.

Methods

Streptozotocin induced diabetic BALB/c mice were transplanted syngeneically under the kidney capsule: 1) 200 islets, 2) 1-5 × 106 bone marrow cells or 3) 200 islets and 1-5 × 106 bone marrow cells. All mice were evaluated for blood glucose, serum insulin and glucose tolerance up to postoperative day (POD) 28 and a subset was monitored for 3 months after transplantation. Histological assessment was performed at POD 3, 7, 14, 28 and 84 for the detection of von Willebrand factor (vWF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), insulin, cluster of differentiation (CD) 34 and pancreatic duodenal homeobox-1 protein (PDX-1).

Results

Blood glucose was lowest and serum insulin was highest in the islet + bone marrow group at POD 7. Blood glucose was significantly lower in the islet + bone marrow group relative to the islet only group after 63 days of transplantation (p<0.05). Significantly more new peri-islet vessels were detected in the islet + bone marrow group compared to the islet group (p<0.05). VEGF staining was more prominent in bone marrow than in islets (p<0.05). PDX-1 positive areas were identified in bone marrow cells with an increase in staining over time. However, there were no normoglycemic mice and no insulin positive cells in the bone marrow alone group.

Conclusions

Co-transplantation of bone marrow cells with islets is associated with enhanced islet graft vascularization and function.

Keywords: Islet Transplantation, Bone Marrow, Angiogenesis, Endothelial precursor cells

Introduction

Islet transplantation has been shown to reverse type 1 diabetes mellitus (1, 2). While the rate of insulin-independence following islet transplantation has improved significantly (1-3), long-term blood glucose control is still largely unachievable (1). To improve the outcome of islet transplantation, one of the critical hurdles to overcome is the lack of a vascular network to support the newly transplanted islets. Endogenous native pancreatic islets are richly vascularized (4). However, the process of isolating islets disrupts this specialized vasculature, thus threatening the survival of cells in the core of the islets (5). Isolated islets are avascular and the vascular network is regenerated within 14 days after transplantation (6). During this time period, transplanted islets suffer from hypoxia. Approximately 60% of islets fail to engraft within 3 days following intraportal islet transplantation (7), and hypoxia at the early post-transplant stages is considered a major reason for early islet graft loss.

Recently, bone marrow transplantation as a cell therapy for clinical disease has been increasingly studied. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) derived from the bone marrow stroma constitute approximately 0.001-0.01% of the nucleated cells in the marrow (8) and can differentiate into various cell types including osteoblasts, adipocytes, cardiomyocytes, and endothelial cells (9). It has been reported that MSCs can also differentiate into islet β cells (10), but other groups have reported little to no differentiation (11, 12). Endothelial precursor cells (EPCs), a heterogeneous group of endothelial cell precursors originating in the hematopoietic compartment of bone marrow (8), are capable of multipotent differentiation (13) and play an important role in angiogenesis of adult tissues (14). Transplanted EPCs induce hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) under hypoxic conditions which leads to upregulation of angiogenic factors, e.g. vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and promotes vascularization (14-16). EPCs also prevent ischemic tissues from undergoing apoptosis (17). Moreover, EPCs themselves contribute to angiogenesis by migration to ischemic lesions and differentiation into endothelial cells (18). Therefore, EPCs may have a beneficial effect to minimize early graft loss after islet transplantation and improve vascularization.

In this study we evaluated the effect of bone marrow co-transplantation with islets on islet graft angiogenesis and function.

Materials and Methods

Animals

BALB/c male mice (22-27g, Charles River Laboratories. Inc., Boston, MA, USA) were used as both donors and recipients. The mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions with a 12-hour light cycle and free access to food and water. All animal care and treatment procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Use Committee.

Induction of diabetes in recipient mice

Streptozotocin (STZ, 200 mg/kg/mouse, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Lois, MO, USA) was injected intraperitoneally and blood glucose levels were measured by Accu-Chek Aviva glucose monitors (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Recipient mice were used when the blood glucose level was greater than 19.3 mmol/L (350mg/dL).

Islet isolation

Murine islets were isolated by collagenase (collagenase V, Sigma-Aldrich) digestion, separated by Ficoll (Sigma-Aldrich) discontinuous gradient and purified as previously described (19). Collected islets were 133-200 μm in size; islets greater than 267μm in size were rejected (20). Based on previous results (21), 200 islets were considered a marginal islet mass for restoring normoglycemia.

Bone marrow cell isolation

The protocol of bone marrow cell isolation was modified from the Soleimani method (22). Under general anesthesia with 2% Isoflurane, hind limb extirpations were performed at the hip, ankle, and ankle joint. Muscle and connective tissue were dissected away from the femur and tibia. They were divided by cutting the knee joint and the top and end of the bones. A thirty gauge needle attached to a 1 mL syringe was inserted into the bone. Bone marrow was flushed by injection of Hanks balanced salt solution (HBSS) prior to its collection. After a single wash, bone marrow was dispersed by incubation with 0.05% trypsin / 0.53mM EDTA solution (Mediatech Inc., Manassas, VA, USA).

Islet and bone marrow cell transplantation

Cell transplantation was performed under the left kidney capsule. Recipients were divided into four groups: 1) Islet group (200 syngeneic islets: N=12), 2) Bone marrow group (1-5 × 106 syngeneic bone marrow cells: N=11), 3) Islet + Bone marrow group (200 syngeneic islets and 1-5 × 106 syngeneic bone marrow cells: N=13) and 4) Sham group (skin and renal capsule incisions with no transplantation: N=5).

Islet function tests

Blood glucose was measured at postoperative day (POD) 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 14, 17, 21, 24, 28. Blood samples for serum insulin were acquired at POD 0, 3, 7 14 and 28. Glucose tolerance test (GTT) was measured at POD 7, 14 and 28. Days to, and the percentage of animals achieving, normoglycemia were calculated. In this study, normoglycemia was defined asa blood glucose level of ≤ 11 mmol/L. Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance tests (GTT) were performed by overnight fasting for 10 hr and then injecting mice with 2.0 g/kg body weight of glucose solution followed by tail vein blood samples at 0, 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes after injection. Blood glucose levels were measured by Accu-Chek Aviva glucose monitors and serum insulin was measured using a rat/mouse insulin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Linco, MO). In another group of mice, blood glucose, serum insulin and GTT were evaluated for up to 3 months to test the long term effects of bone marrow cell co-transplantation.

Histological assessment

Kidney and pancreatic specimens were acquired from three or more mice at POD 3, 7, 14, 28 and 84 and photographs of the fresh organs were obtained to assess the density of new vessels around islets / bone marrow. Tissue was then fixed with 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin and cut into 5 μm sections. Specimens were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) to identify cellular changes. Immunohistochemical staining was done for insulin to identify islets, cluster of differentiation (CD) 34 to detect bone marrow cells, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) for angiogenesis, PDX-1 for regeneration of insulin producing cells, and von Willebrand Factor (vWF) for newly formed blood vessels. For vWF and PDX-1 staining, specimens were treated with Proteinase K (Dako, Carpenteria, CA). Primary antibodies were guinea pig anti-insulin antibody (Dako, Carpenteria, CA, USA) diluted 1:100, rabbit anti-CD34 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA) diluted 1:100, goat anti VEGF (p-20) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) diluted 1:50, rabbit anti-vWF (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) diluted 1:2000 and goat anti-PDX-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.) diluted 1:100. After incubating with biotinylated secondary IgG antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA and Santa Cruz Inc.), a peroxidase substrate solution containing 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Brown, Dako) or AEC+ (Red for insulin, Dako) was used for visualization and counterstained with hematoxylin (23). Alexa Fluor® 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (identifying insulin and CD34) and Alexa Fluor® 568 rabbit anti-goat IgG (identifying VEGF and PDX-1) were used for fluorescent staining. Apoptosis was detected by the TdT-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) method using an in situ apoptosis detection kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Sections were treated with proteinase K and incubated with TdT enzyme for 60 min at 37°C. After washing in PBS, the sections were further incubated with streptavidin horseradish peroxidase (HRP) solution and visualized with DAB (20).

The percentage of VEGF expression in islets (insulin positive areas) or bone marrow cells (CD34 positive areas) was assessed as follows: VEGF positive area (in red) divided by insulin or CD34 positive area (in green) multiplied by 100 (%). Islet apoptosis was expressed as a percentage of TUNEL positive islets relative to total islets [TUNEL positive cells] / [Total islet cells] × 100 (%). vWF positive vessel numbers were calculated from vWF positive lumens at the transplant site.

Pancreatic specimens were collected for counting residual native islets and evaluating PDX-1 positive areas in islet, and β cell regeneration was compared in all treatment groups at POD 28 (islet transplants, bone marrow transplants and islet + bone marrow transplants). Image analyses were performed using image analysis software (Image J ver. 1.40, NIH, USA).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Statistical analyses were performed using JMP 5.0.1J for Macintosh (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Dunnet test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed for statistical analysis of all results except the percentage of normoglycemia which was performed by the Kaplan Meyer method and Log rank testing. Significance was designated at p < 0.05.

Results

Blood glucose, serum insulin and GTT

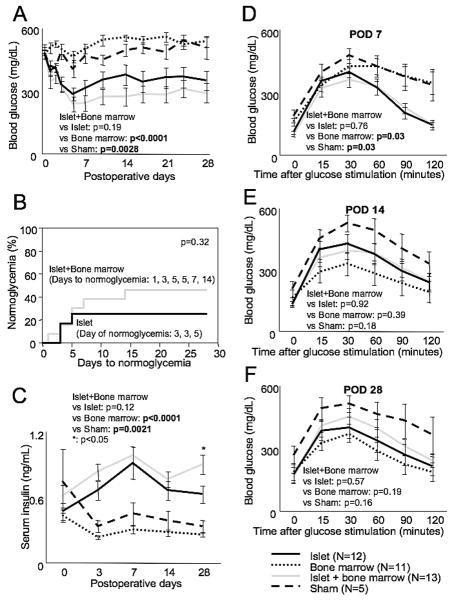

Blood glucose levels were lowest in the islet + bone marrow group and significantly lower than the bone marrow (p<0.0001) and sham groups (p<0.003) (Figure 1A). The percentage of animals reaching normoglycemia was higher in the islet + bone marrow group than in the islet alone group (46.2%, 6/13 vs. 25%, 3/12, p=0.32, Figure 1B). There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the time to normoglycemia (3.7±0.5 days for islet alone vs. 5.8±1.7 days for islet+bone marrow, Figure 1B). There were no normoglycemic mice in the bone marrow only or sham groups. Serum insulin was significantly higher in the islet + bone marrow group compared to the islet alone group at POD 28 (p<0.05, Fig 1C). Serum insulin was higher in the islet+bone marrow group compared to bone marrow only and sham groups at all time points (Figure 1C). Glucose tolerance in both the islet alone and the islet + bone marrow groups was significantly improved relative to the bone marrow alone and sham groups at POD 7 (p=0.03 both, Figure 1D). Interestingly, glucose tolerance appeared better in the bone marrow alone group than the other groups at POD's 14 and 28 (Figure 1E and F).

Figure 1.

Blood glucose (A) and serum insulin (C) after islet and / or bone marrow transplantation up to postoperative day (POD) 28. Blood glucose was lowest in the islet + bone marrow group and was decreased significantly compared to the bone marrow and sham groups. The same tendency was observed in serum insulin, which was highest in the islet + bone marrow group. There was a significant increase in serum insulin in the islet + bone marrow group relative to the islet group at POD 28. The percentage of animals reaching normoglycemia (B) was higher in the islet + bone marrow group (46.2%, 6/13) than in the islet group (25%, 3/12) (p=0.32) and there were no normoglycemic mice in the bone marrow only or sham groups. There was also no significant difference between the islet (3.7±0.5 days) and islet + bone marrow (5.8±1.7 days) groups in the days to normoglycemia (B). Glucose tolerance tests (GTT) at POD 7 (D), POD 14 (E) and POD 28 (F) revealed that there was a significant improvement in the islet + bone marrow group compared to the bone marrow and sham groups at POD 7. Statistical analysis was performed by two ways repeated measurement ANOVA and significant difference was p<0.05.

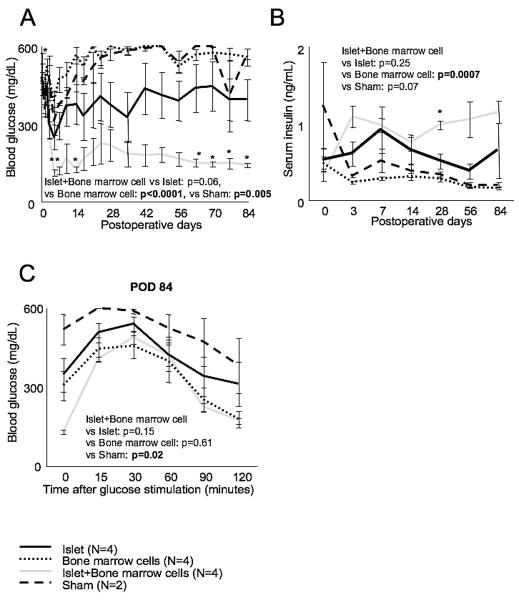

In long term observations (up to 3 months), the islet + bone marrow group had lower blood glucose than the islet alone group (p=0.06), and this trend became significant at POD's 63-84 (p<0.05, Figure 2A). Serum insulin was higher and the GTT AUC was lower in the islet + bone marrow group compared to the islet alone group, though the difference was not significant (Figure 2B and C). In summary, islets co-transplanted with bone marrow cells had improved function compared to islet alone transplants in diabetic recipients.

Figure 2.

Blood glucose (A), serum insulin (B) and GTT (C) after transplantation up to POD 84. Mice were selected randomly for either histological assessment or for long term observation. Blood glucose decreased significantly in the islet + bone marrow group compared to the islet group about two months after transplantation (= POD 63, 70, 77 and 84). Serum insulin was also increased at POD 28. No significant difference was seen between islet + bone marrow and islet groups in GTT. Statistical analysis was performed by two ways repeated measurement ANOVA and significant difference was p<0.05.

Angiogenesis observed with transplantation of bone marrow cells

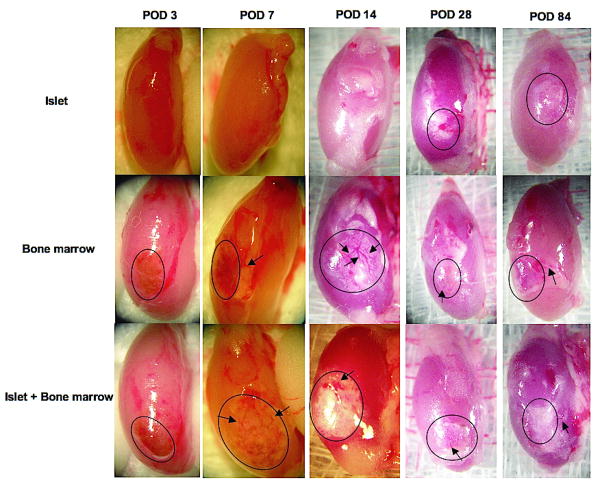

Photographs of the excised kidney at POD 3 revealed no evidence of neovascularization in or around the transplant sites in any of the experimental groups (Figure 3). At POD 7, newly formed vessels were observed in the bone marrow alone and the islet + bone marrow groups (Figure 3). At POD 14, angiogenesis appeared more prominent in bone marrow alone and islet + bone marrow groups relative to the islet alone group (Figure 3). At days 28 and 84, mature vasculature was observed in the bone marrow and islet + bone marrow groups.

Figure 3.

Photomicrographs of fresh kidneys recovered from islet, bone marrow and islet + bone marrow group mice at POD3, 7, 14, 28 and 84. While new vessels could not be detected in any groups at POD 3, we saw newly formed vessels (arrows) in and around the transplant site (outline) in bone marrow and islet + bone marrow groups at POD 7 and more prominently at POD 14. Mature vasculature was seen at POD 28 and 84.

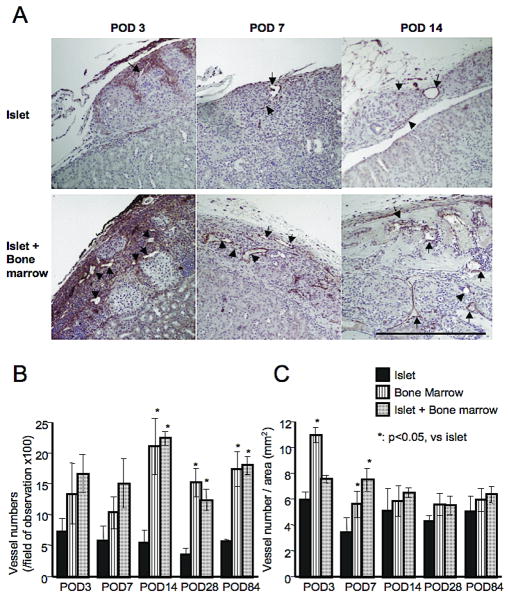

Histological analysis revealed significantly more new vessels in bone marrow and islet + bone marrow groups relative to the islet alone group at POD's 14, 28 and 84 (p<0.05, Figure 4A and B). The number of new vessels found per transplanted tissue area (mm2) was significantly higher in bone marrow and islet + bone marrow transplant groups at POD 7 (Figure 4C). Vascularization was more prominent in bone marrow (+ islet) transplantation than in islet alone transplantation.

Figure 4.

vWF staining of subcapsular grafts. A. More new vessels (positive for vWF, indicated as arrow) could be detected in the islet + bone marrow group than in the islet group. (magnification = 100x and bar = 500 μm). B. Vessel numbers in the field of view (magnification is 100x) were significantly more in bone marrow and islet + bone marrow groups compared to the islet group at POD 14, 28 and 84. C. Vessel numbers divided by graft area (mm2) were also significantly more in bone marrow and islet + bone marrow groups at POD 3 and 7. Statistical analysis was performed by Dunnet test and significant difference was p<0.05.

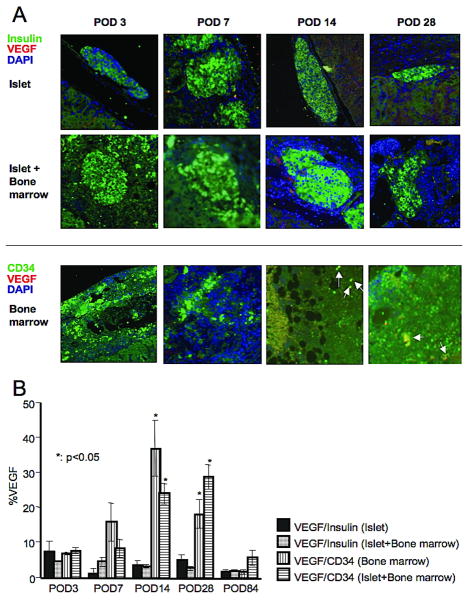

Assessment of VEGF expression

VEGF expression within islet tissue was not prominent during the experimental period in both the islet and islet + bone marrow groups and there was no significant difference between the two groups (Figure 5A and B). However, VEGF expression in bone marrow cells was significantly increased in both bone marrow alone and islet + bone marrow groups at POD's 14 and 28 compared to the islet alone group (Figure 5A and B, p<0.05). These results suggest that enhanced peri-islet angiogenesis in this study was dependent on the presence of bone marrow cells.

Figure 5.

A. Fluorescent double staining for insulin and VEGF (upper) and for CD34 and VEGF (lower). VEGF staining was more prominent within CD34 positive cells (=bone marrow cells) than within insulin positive cells (=β cells) at POD 14 and 28. B. Ratio of VEGF positive area to total CD34 positive or insulin positive cells area (=%VEGF). The ratio was significantly higher in VEGF/CD34 (both bone marrow and islet bone marrow groups) than VEGF/insulin in islet group. Statistical analysis was performed by Dunnet test and significant difference was p<0.05.

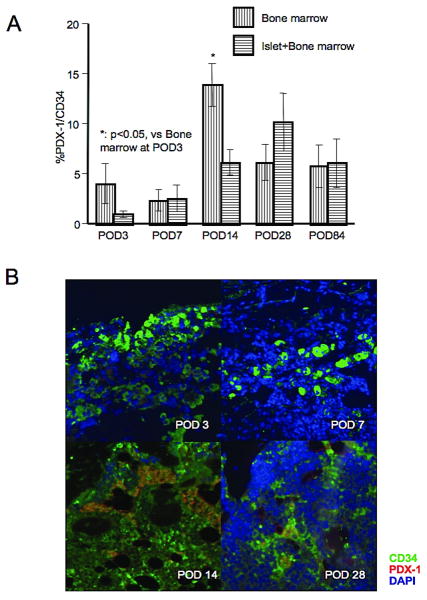

Regeneration of β cells

The expression of PDX-1 was investigated in transplanted bone marrow to monitor the development of islet cell precursors. While PDX-1 expression was low at POD 3 and 7 in both bone marrow and islet + bone marrow groups, it increased by ∼10 % at POD's 14 and 28. There was a significant difference between POD 3 and 14 in the bone marrow group (3.9 ± 2.0 % vs. 13.9 ± 2.1 %, p<0.05, Figure 6A and B). However, insulin positive cells were not detectable at any time point up to POD 84.

Figure 6.

A. Ratio of PDX-1 positive area to CD34 positive area in bone marrow and islet + bone marrow groups. Change in the ratio over time within each group was tested. Significant difference was seen in the bone marrow group between POD 3 and 14. B. Fluorescent double staining for PDX-1 (red) and CD34 (green). Double stained cells were seen at POD 14 and 28. Statistical analysis was performed by Dunnet test and significant difference was p<0.05.

There was also no significant difference in either the number of residual native pancreatic islets or the number of PDX-1 positive pancreatic islets among experimental groups (islet alone, bone marrow alone, and islet + bone marrow, Supplemental Figure 1A and B).

Other histological findings

TUNEL staining revealed few or no apoptotic cells within islets throughout this study in both the islet alone and the islet + bone marrow groups (data not shown).

Discussion

Bone marrow consists of blood cells and precursor cells. MSCs and EPCs derived from bone marrow cells, have emerged as useful substrates for neovascularization (8). Previous studies revealed that mesenchymal cells have an ability to promote angiogenesis and vascularization by producing some angiogenic factors under hypoxic conditions in vitro (24), and animal MSC and / or EPC transplantation study models also revealed their effectiveness in promoting angiogenesis and improving local ischemia in ischemic heart disease (25), cerebral infarction (26, 27) and leg ischemia (28, 29) models. In this study, syngeneic bone marrow cells were transplanted to evaluate their effect on islet graft function and angiogenesis.

Bone marrow co-transplantation with islets in a type 1 diabetes model yielded the following results in this study: 1) lower blood glucose and elevated serum insulin, 2) an improvement of blood glucose three months after transplantation and 3) more prominent vascularization and expression of VEGF. It appeared that bone marrow cells released the angiogenic factor VEGF throughout the post-transplantation period, while VEGF released from islets was minimal and decreased over time. The result was continued angiogenesis with bone marrow transplantation. This enhanced vascularization correlated with improved islet function.

The origin of the enhanced vasculature observed with bone marrow co-transplantation, and the mechanism by which it develops, remain to be elucidated. Labeled animal models, e.g. GFP transgenic mice or congeneic Ly antigen mice, could serve as a useful tool to detect the origin of bone marrow transplant-associated neovasculature. It would also be of value to investigate whether there is a direct contribution of bone marrow cells or an effect mediated by proangiogenic products of bone marrow. While the purpose of this study was the detection of any effect of bone marrow co-transplantation on islets, further studies are needed to investigate the mechanism of the effects described above.

Previous studies have examined the role of bone marrow derived cells in the regeneration of β cells. It has been reported that MSCs can differentiate into β cells under certain conditions (10), but other studies have reported low to non-existent regeneration rates (11, 12). Some PDX-1 positive cells were detected but no insulin positive cells were detected in bone marrow in this study. Additionally, no diabetic mice with bone marrow only transplants had lower blood glucose even up to 3 months following transplantation. While hyperglycemia may be one of the important triggers for bone marrow cells to differentiate into insulin producing cells, the above results suggest that hyperglycemia alone is not sufficient to result in complete differentiation of bone marrow precursors into beta cells within a three month time-frame.

As for the lack of detection of islet apoptosis up to POD 84 in either islet or islet + bone marrow groups, this may be due to the relatively mild hypoxia of aggregated renal subcapsular grafts in comparison to dispersed intrahepatic (intraportal) grafts. The liver is suspected to be a non-ideal transplant site as previously evidenced by severe hypoxia and apoptosis at the early stages following transplantation (20, 21, 30). Therefore, it may be even more effective to co-transplant bone marrow cells intraportally to prevent islet hypoxia.

The beneficial effect of bone marrow co-transplantation with islets may be due to mesenchymal cells. We used whole bone marrow cells and did not isolate and use mesenchymal cells alone, akin to a clinical setting where islet isolation and transplantation is typically an emergency precluding adequate time for mesenchymal cell isolation and pre-transplant culture. Bone marrow cells can be acquired from brain-dead donors concomitant with a pancreatectomy allowing co-transplantation with islets from the same donor. However, safety and effectiveness of whole bone marrow co-transplantation with islets need to be verified retrospectively in animal models prior to clinical translation.

In conclusion, bone marrow transplantation has various potential benefits in the treatment of diabetes (10, 31-35). In this study, bone marrow transplantation with islets was associated with enhanced angiogenesis and improved islet function. Co-transplantation of bone marrow should be included among potential therapeutic strategies aiming at improving the outcome of clinical islet transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. A. Number of residual islets in pancreas B. Ratio of PDX-1 positive area in residual pancreatic islets in islet, bone marrow, and islet + bone marrow groups at POD 28. There were no significant differences between the three groups with a similar trend for islet regeneration among the three groups. Statistical analysis was Dunnet test and significant difference was p<0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIDDK Grant # 1R01-DK077541 [EH] and a grant from the National Medical Test Bed [EH]. We are very appreciative of the microsurgical technical support of the Loma Linda University Microsurgery Laboratory and the kind help in specimen processing by John Hough.

Funding sources: NIH/NIDDK Grant # 1R01-DK077541 [EH] and a grant from The National Medical Test Bed [EH].

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CD

cluster of differentiation

- DAB

3,3′ -diaminobenzidine

- EPCs

endothelial precursor cells

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- GTT

glucose tolerance test

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- HBSS

Hanks Balanced salt solution

- HIF-1α

hypoxia inducible factor-1α

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- MSCs

mesenchymal stem cells

- PDX-1

pancreatic duodenal homeobox-1 protein

- POD

postoperative day

- STZ

streptozotocin

- TUNEL

TdT-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

- vWF

von Willibrand factor

Footnotes

Authorship: NS designed and performed the study and wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. NKC helped in writing this manuscript. JC performed animal surgeries. AO helped in writing this manuscript. EH helped with the design, supervised data collection, and wrote the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Ryan EA, Paty BW, Senior PA, et al. Five-year follow-up after clinical islet transplantation. Diabetes. 2005;54(7):2060. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.7.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shapiro AM, Nanji SA, Lakey JR. Clinical islet transplant: current and future directions towards tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2003;196:219. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-065x.2003.00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shapiro AM, Lakey JR, Ryan EA, et al. Islet transplantation in seven patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus using a glucocorticoid-free immunosuppressive regimen. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(4):230. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stagner JI, Mokshagundam S, Samols E. Hormone secretion from transplanted islets is dependent upon changes in islet revascularization and islet architecture. Transplant Proc. 1995;27(6):3251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emamaullee JA, Rajotte RV, Liston P, et al. XIAP overexpression in human islets prevents early posttransplant apoptosis and reduces the islet mass needed to treat diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54(9):2541. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menger MD, Yamauchi J, Vollmar B. Revascularization and microcirculation of freely grafted islets of Langerhans. World J Surg. 2001;25(4):509. doi: 10.1007/s002680020345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biarnes M, Montolio M, Nacher V, Raurell M, Soler J, Montanya E. Beta-cell death and mass in syngeneically transplanted islets exposed to short- and long-term hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 2002;51(1):66. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunt KR, Hall SR, Ward CA, Melo LG. Endothelial progenitor cell and mesenchymal stem cell isolation, characterization, viral transduction. Methods Mol Med. 2007;139:197. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-571-8_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satija NK, Singh VK, Verma YK, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-based Therapy: A New Paradigm in Regenerative Medicine. J Cell Mol Med. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00857.x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasegawa Y, Ogihara T, Yamada T, et al. Bone marrow (BM) transplantation promotes beta-cell regeneration after acute injury through BM cell mobilization. Endocrinology. 2007;148(5):2006. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choi JB, Uchino H, Azuma K, et al. Little evidence of transdifferentiation of bone marrow-derived cells into pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia. 2003;46(10):1366. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lechner A, Yang YG, Blacken RA, Wang L, Nolan AL, Habener JF. No evidence for significant transdifferentiation of bone marrow into pancreatic beta-cells in vivo. Diabetes. 2004;53(3):616. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roitbak T, Li L, Cunningham LA. Neural stem/progenitor cells promote endothelial cell morphogenesis and protect endothelial cells against ischemia via HIF-1alpha-regulated VEGF signaling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28(9):1530. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sepulveda P, Martinez-Leon J, Garcia-Verdugo JM. Neoangiogenesis with endothelial precursors for the treatment of ischemia. Transplant Proc. 2007;39(7):2089. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milovanova TN, Bhopale VM, Sorokina EM, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen stimulates vasculogenic stem cell growth and differentiation in vivo. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106(2):711. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91054.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dai Y, Xu M, Wang Y, Pasha Z, Li T, Ashraf M. HIF-1alpha induced-VEGF overexpression in bone marrow stem cells protects cardiomyocytes against ischemia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42(6):1036. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang M, Wang B, Wang C, et al. Angiogenesis by transplantation of HIF-1 alpha modified EPCs into ischemic limbs. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103(1):321. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang M, Wang B, Wang C, et al. Inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and endothelial progenitor cell differentiation by adenoviral transfer of small interfering RNA in vitro. J Vasc Res. 2006;43(6):511. doi: 10.1159/000095964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gotoh M, Maki T, Kiyoizumi T, Satomi S, Monaco AP. An improved method for isolation of mouse pancreatic islets. Transplantation. 1985;40(4):437. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198510000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakata N, Hayes P, Tan A, et al. MRI assessment of ischemic liver after intraportal islet transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;87(6):825. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318199c7d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakata N, Tan A, Chan N, et al. Efficacy comparison between intraportal and subcapsular islet transplants in a murine diabetic model. Transplant Proc. 2009;41(1):346. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2008.08.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soleimani M, Nadri S. A protocol for isolation and culture of mesenchymal stem cells from mouse bone marrow. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):102. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miao G, Ostrowski RP, Mace J, et al. Dynamic production of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha in early transplanted islets. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(11):2636. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Santo S, Yang Z, Wyler von Ballmoos M, et al. Novel cell-free strategy for therapeutic angiogenesis: in vitro generated conditioned medium can replace progenitor cell transplantation. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(5):e5643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z, Guo J, Chang Q, Zhang A. Paracrine role for mesenchymal stem cells in acute myocardial infarction. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32(8):1343. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chung DJ, Choi CB, Lee SH, et al. Intraarterially delivered human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells in canine cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci Res. 2009 doi: 10.1002/jnr.22162. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu N, Chen R, Du H, Wang J, Zhang Y, Wen J. Expression of IL-10 and TNF-alpha in rats with cerebral infarction after transplantation with mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2009;6(3):207. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2009.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laurila JP, Laatikainen L, Castellone MD, et al. Human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stromal cell transplantation in a rat hind limb injury model. Cytotherapy. 2009;1 doi: 10.3109/14653240903067299. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawamoto A, Katayama M, Handa N, et al. Intramuscular Transplantation of Granulocyte Colony Stimulating Factor-Mobilized CD34-Positive Cells in Patients with Critical Limb Ischemia: A Phase I/IIa, Multi-Center, Single-Blind and Dose-Escalation Clinical Trial. Stem Cells. 2009 Epub ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakata N, Obenaus A, Chan NK, Mace J, Chinnock R, Hathout E. Factors affecting islet graft embolization in the liver of diabetic mice. Islets. 2009;1(1):26–33. doi: 10.4161/isl.1.1.8563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akashi T, Shigematsu H, Hamamoto Y, et al. Bone marrow or foetal liver cells fail to induce islet regeneration in diabetic Akita mice. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2008;24(7):585. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chan J, Clements W, Field J, et al. Transplantation of bone marrow genetically engineered to express proinsulin II protects against autoimmune insulitis in NOD mice. J Gene Med. 2006;8(11):1281. doi: 10.1002/jgm.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ikebukuro K, Adachi Y, Suzuki Y, et al. Synergistic effects of injection of bone marrow cells into both portal vein and bone marrow on tolerance induction in transplantation of allogeneic pancreatic islets. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38(10):657. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller R, Cirulli V, Diaferia GR, et al. Switching-on survival and repair response programs in islet transplants by bone marrow-derived vasculogenic cells. Diabetes. 2008;57(9):2402. doi: 10.2337/db08-0244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakayama S, Uchida T, Choi JB, et al. Impact of whole body irradiation and vascular endothelial growth factor-A on increased beta cell mass after bone marrow transplantation in a mouse model of diabetes induced by streptozotocin. Diabetologia. 2009;52(1):115. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1172-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. A. Number of residual islets in pancreas B. Ratio of PDX-1 positive area in residual pancreatic islets in islet, bone marrow, and islet + bone marrow groups at POD 28. There were no significant differences between the three groups with a similar trend for islet regeneration among the three groups. Statistical analysis was Dunnet test and significant difference was p<0.05.