Abstract

Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Surinam is generally caused by infection by Leishmania guyanensis. We report three cases of infection with Leishmania (Viannia) naiffi, a Leishmania species not described from Surinam before. Treatment with pentamidine proved to be effective.

Introduction

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is endemic in many parts of the world. The geographical distribution of the more than 10 pathogenic Leishmania species depends on reservoir and vector. Clinical manifestations, type of and response to treatment vary according to the species. In endemic areas several species with different sensitivities to specific drugs may occur concurrently, making interpretation of treatment results difficult if parasite species are not identified. For comparison of results between different regions, species identification is necessary. For this purpose, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is the diagnostic method of choice because it is fast and combines high sensitivity and specificity. In non-endemic settings, species identification is also important as travelers may have visited various areas where, as mentioned, different species may circulate.

Over the last decades, in the Netherlands like in the UK, a considerable rise was seen in the number of patients with imported cutaneous leishmaniasis, with Latin America as the most important source of infection.1 In Surinam, Leishmania (Viannia) guyanensis is the main cause of cutaneous leishmaniasis, though recently cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania (Viannia) lainsoni and Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis were reported.2,3

We describe three military patients who presented with lesions that developed after jungle training in Surinam. With PCR-analysis,4 all three proved infected with Leishmania naiffi, a Leishmania species not reported before in Surinam.

Case reports.

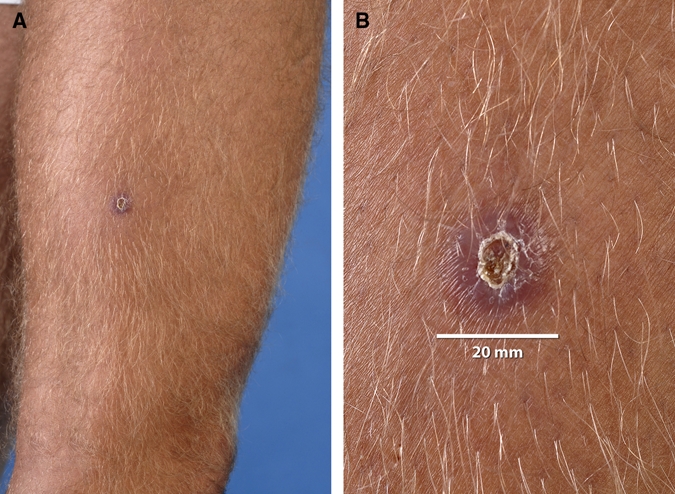

Three Dutch male military A, B (both 22 years of age) and C (21 years of age), noticed skin lesions after a period of jungle training in Surinam northwest of Brokopondo Lake, in 2006 (patients A and B) and 2008 (patient C), respectively. Patient C discovered the lesions immediately after the training and reported to the medical service 4 months later because of persistence of the lesions. Patients A and B noticed the lesions 2–3 months after the training period and as the lesions did not heal, they came to the medical service 1, respectively, 2 months later. Patient A presented with two nodular lesions with a central crust (15 and 20 mm in diameter, respectively) on the right upper leg (Figure 1), patient B with a nodule with a crust (8 mm in diameter) on the left hip, and patient C with two small papular lesions with a crust, on the right ankle (10 mm) and left dorsal foot (2 mm). Under the crust of all lesions a small ulcer was present. None of the patients had lymphadenopathy. The lesions had not shown a remarkable increase in size during the period of presence that lasted from 1 to 4 months.

Figure 1.

Skin lesions right upper leg of patient A. A, Overview and B, detail. This figure appears in color at www.ajtmh.org.

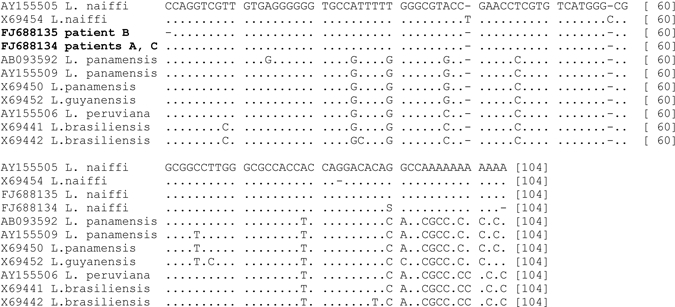

As leishmaniasis was suspected, biopsies were taken and examined by microscopy of smears (Giemsa stain), culture on Novy-McNeal-Nicolle (NNN)-medium, and by mini-exon repeat PCR. The protocol described by Marfurt and others4 was slightly modified, using 5 and 4 nucleotides extended versions of the primers originally described (primers Fme2, 5′-ACT TTA TTG GTA TGC GAA ACT TCC GG-3′, and Rme2 5′-ACA GAA ACT GAT ACT TAT ATA GCG TTA G-3′). Mini-exon PCR products were sequenced with primer Rme2 using BigDye Terminator (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) chemistry and analyzed on an ABI 3730 automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Nucleotide sequences were submitted to the Genbank database under accession nos. FJ688134 and FJ688135. Culture and PCR were positive for Leishmania parasites in biopsies of all three patients; microscopy was positive in the biopsies of both lesions of patient A only. The size of the PCR products from the lesions, ~220 bp, indicated that the causative species were members of the subgenus Viannia. This was confirmed by sequence analysis, revealing 100% identity over 102 nucleotides to the sequence of the L. (V.) naiffi reference strain MDAS/BR/79/M5533 (Genbank accession no. AY155505), differing at 15 or more positions from the other Viannia species L. (V.) braziliensis, L. (V.) peruviana, L. (V.) guyanensis, and L. (V.) panamensis database sequences, respectively (Figure 2). The sequence obtained from the biopsy of patient B differed at one site from the sequences obtained from biopsies of the other two patients, which showed sequence heterogeneity at this position.

Figure 2.

Alignment of partial sequences of the mini-exon repeat obtained for Leishmania parasites from patients and reference sequences of Leishmania Viannia species. Reference sequences are indicated by Genbank accession number, followed by species name. Sequences obtained from patients are indicated by Genbank accession number in boldface, followed by patient identifier. Dots indicate identical positions, dashes indicate alignment gaps. Alignment positions are given at the end of each line.

All three were successfully treated as outpatients with pentamidine isethionate (4 mg salt/kg body weight), intravenously, given 4 times with 2–4 days interval. They experienced no adverse event. Six months after treatment no relapse had occurred and small atrophic scars were noted.

Discussion

The three reported patients were infected with L. (V.) naiffi and represent the first confirmed cases of L. (V.) naiffi infection from Surinam. Leishmania (V.) naiffi was first described by Lainson and Shaw in 19895 as a parasite of Dasypus novemcinctus, the nine-banded armadillo, in Amazonian Brazil. Subsequently, cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by L. (V.) naiffi infection was observed in nine patients from Brazil,6–9 whereas armadillos were confirmed to be a reservoir.6,8 Six more human cases were described, one probably from Martinique/Guadeloupe,10 the others from a wide area stretching from French Guyana to Ecuador/Peru.11,12 The patients were successfully treated with parenteral antimony or pentamidine. Five of six patients for whom the occupation was mentioned were military.8,10,11 It is possible that military manoeuvres are associated with different epidemiological circumstances than those for non-military visitors and the endemic population.13

The reservoir host of L. (V.) naiffi, D. novemcinctus is frequently found in rural areas of Surinam14 and the suspected vector, Lutzomyia (Psychodopygus) paraensis,6 is present in Surinam.15 On questioning, our three patients admitted they had been in close contact with armadillos. Because both host and vector are present in a wide geographical area, L. (V.) naiffi is probably widespread in South America,11 but how often human infection occurs is unknown. The distinction of L. naiffi from other Leishmania species requires relatively sophisticated molecular or biochemical methods, which are available to a limited extent only. Our patients presented with small papulo-nodular lesions without prominent ulceration and with hardly any tendency to increase in size, a picture that also arises from the few limited descriptions in the literature.5,7,8,10,11 Therefore, it is quite possible that L. naiffi infection is underdiagnosed as patients with this eventually self-limiting skin problem may not present themselves. This could be very well applicable to people living in isolated parts of the Amazonian region.

In conclusion, L. (V.) naiffi, earlier described in other parts of the Amazonian region, is also present in Surinam, in relation to the occurrence of its reservoir host D. novemcinctus (armadillo). In our patients the infection presented itself with persistent papulo-nodular lesions with a crust covering a small ulcer and without tendency to increase in size. Treatment with pentamidine as used for L. guyanensis infection, the most common Leishmania parasite in Surinam, was effective.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Carla Wassenaar and Nienke Verhaar for excellent technical support.

Footnotes

Authors' addresses: Pieter-Paul A. M. van Thiel and Piet A. Kager, Department of Infectious Diseases, Tropical Medicine and Aids, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, E-mail: p.p.vanthiel@amc.uva.nl. Tom van Gool and Aldert Bart, Section Parasitology, Department of Medical Microbiology, Academic Medical Center, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

References

- 1.Schwartz E, Hatz C, Blum J. New world cutaneous leishmaniasis in travellers. Lancet Infect Dis. 2006;6:342–349. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70492-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Meide WF, Jensema AJ, Akrum RA, Sabajo LO, Lai A Fat RF, Lambregts L, Schallig HD, van der Paardt M, Faber WR. Epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Suriname: a study performed in 2006. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:192–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van der Meide W, de Vries H, Pratlong F, van der Wal A, Sabajo L. Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis infection, Suriname. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:857–859. doi: 10.3201/eid1405.070433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marfurt J, Niederwieser I, Makia ND, Beck HP, Felger I. Diagnostic genotyping of Old and New World Leishmania species by PCR-RFLP. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2003;46:115–124. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(03)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lainson R, Shaw JJ. Leishmania (Viannia) naiffi sp. n., a parasite of the armadillo, Dasypus novemcinctus (L.) in Amazonian Brazil. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 1989;64:3–9. doi: 10.1051/parasite/19896413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grimaldi G, Jr, Momen H, Naiff RD, Mahon-Pratt D, Barrett TV. Characterization and classification of leishmanial parasites from humans, wild mammals, and sand flies in the Amazon region of Brazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;44:645–661. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.44.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lainson R, Shaw JJ, Silveira FT, Braga RR, Ishikawa EA. Cutaneous leishmaniasis of man due to Leishmania (Viannia) naiffi Lainson and Shaw, 1989. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 1990;65:282–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naiff RD, Freitas RA, Naiff MF, Arias JR, Barrett TV, Momen H, Grimaldi GJ. Epidemiological and nosological aspects of Leishmania naiffi Lainson & Shaw, 1989. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1991;86:317–321. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761991000300006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tojal da Silva AC, Cupolillo E, Volpini AC, Almeida R, Romero GA. Species diversity causing human cutaneous leishmaniasis in Rio Branco, state of Acre, Brazil. Trop Med Int Health. 2006;11:1388–1398. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darie H, Deniau M, Pratlong F, Lanotte F, Talarmin A, Millet P, Houin R, Dedet JP. Cutaneous leishmaniasis of humans due to Leishmania (Viannia) naiffi outside Brazil. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:476–477. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pratlong F, Deniau M, Darie H, Eichenlaub S, Pröll S, Garrabe E, le Guydec T, Dedet JP. Human cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania naiffi is wide-spread in South America. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2002;96:781–785. doi: 10.1179/000349802125002293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotureau B, Ravel C, Nacher M, Couppié P, Curtet I, Dedet JP, Carme B. Molecular epidemiology of Leishmania (Viannia) guyanensis in French Guiana. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:468–473. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.468-473.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lainson R. Ecological interactions in the transmission of the leishmaniases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998;321:389–404. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1988.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Husson AM. The Mammals of Suriname. Leiden: Brill Archive; 1978. pp. 263–264. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruijning CF. Man-biting sandflies (Phlebotomus) in the endemic leishmaniasis area of Surinam. Doc Med Geogr Trop. 1957;9:229–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]