Abstract

Background: An increase in the proportion of vegetables at meals could help achieve recommended vegetable intakes and facilitate weight management.

Objective: We investigated the effects on food and energy intakes of varying the portion size and energy density of a vegetable that was added to a meal or substituted for other foods.

Design: In 2 experiments with crossover designs, men and women were served a meal of a vegetable, grain, and meat. Across the meals, the vegetable was served in 3 portion sizes (180, 270, or 360 g) and 2 energy densities (0.8 or 0.4 kcal/g) by altering the type and amount of added fat. In the addition study (n = 49), as the vegetable portion was increased, amounts of the grain and meat were unchanged, whereas in the substitution study (n = 48), amounts of the grain and meat decreased equally.

Results: An increase in the vegetable portion size resulted in greater vegetable consumption in both studies (mean ± SE: 60 ± 5 g; P < 0.0001). The addition of more of the vegetable did not significantly affect meal energy intake, whereas substitution of the vegetable for the grain and meat decreased meal energy intake (40 ± 10 kcal; P < 0.0001). A reduction in vegetable energy density decreased meal energy intake independent of portion size (55 ± 9 kcal; P < 0.0001). By combining substitution with a reduction in energy density, meal energy intake decreased by 14 ± 3%.

Conclusions: Serving more vegetables, either by adding more or substituting them for other foods, is an effective strategy to increase vegetable intake at a meal. However, to moderate meal energy intake, vegetables should be low in energy density; furthermore, the substitution of vegetables for more energy-dense foods is more effective than simply adding extra vegetables.

INTRODUCTION

Most people eat less than recommended amounts of vegetables (1, 2) despite the known health benefits (3) and the possibility that increased consumption could help moderate energy intake and facilitate weight management (4–6). Several health organizations proposed serving more vegetables at meals to encourage consumption. Specifically, it was suggested that foods served on a plate should be reportioned to include a greater proportion of vegetables and a smaller proportion of animal proteins and grains (7–10). This approach has the potential to increase the intake of vegetables and decrease meal energy density and, thus, energy intake (11–13) because vegetables are often the part of the meal with the lowest energy density. However, to our knowledge, there are no data available to indicate whether serving more vegetables at a meal influences the type or amount of food consumed by adults. In the current study, we served meals consisting of a vegetable, grain, and meat and examined the effects on food consumption and energy intake of varying the portion size and energy density of the vegetable in relation to the other meal components.

A number of controlled laboratory-based studies (14–16) in adults showed that providing larger portions of energy-dense foods leads to a substantial increase in food and energy intakes at a single meal and over several days. Even when the portion sizes of all available foods were increased for an 11-d period, the effect on daily energy intake was persistent (16). Of particular interest was that serving larger portions increased the intake of foods in all categories except fruit (as a snack) and vegetables (16). This lack of effect may have been because increasing the portion size of low-energy-dense foods such as vegetables has little influence on consumption or because such foods cannot compete with large portions of accompanying palatable, energy-dense foods.

To determine whether increasing the portion size of a low-energy-dense food can affect intake and to assess the influence of the portion size of the other meal components, we conducted 2 experiments. In one experiment, more of the vegetable was added to the meal while keeping the portions of the meat and grain constant (the addition study); in the other experiment, more of the vegetable was substituted for the other meal components so that the meat and grain were served in smaller portions (the substitution study). It is important to understand how the addition of vegetables to a meal affects intake compared with substituting them for other components because current government advice stresses the importance of substitution, even suggesting that adding vegetables could increase energy intake and lead to weight gain (17, 18).

It is likely that any effect that vegetables have on energy intake will depend on their energy density and influence on the overall energy density of the meal (11–13). The energy density of vegetables can vary widely and typically increases as sauces and fats are added. On the basis of the results of previous research (19, 20), it is likely that the effects of the energy density of foods add to the effects of their portion size to determine energy intake at a meal. Therefore, we reduced the energy density of the vegetable by altering the type and amount of added fat to test how energy density affects the response to variations in the portion size of a vegetable served at a meal.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Experimental design

Two studies were conducted in different groups of adults; each study used a crossover design with repeated measures within participants. In both studies, a midday meal of a vegetable, grain, and meat was served to participants once a week. Across the meals, the vegetable was increased in portion size (180, 270, or 360 g) and reduced in energy density (from 0.8 to 0.4 kcal/g). In the addition study, as the vegetable portion was increased, the amounts of the meat and grain were not changed; thus, the total amount of food served at the meal was increased. In the substitution study, as the vegetable portion was increased, the amounts of the meat and grain were decreased equally; thus, the total amount of food served at the meal did not change. In each study, the order of presenting the experimental conditions was randomly assigned across participants.

Subject recruitment and characteristics

Participants for both studies were recruited by advertisements in a local newspaper and by notices distributed electronically to university mailing lists; recruitment began on 4 September 2007. Potential participants were interviewed by telephone to determine whether they met the following inclusion criteria: were between the ages of 20 and 45 y, had a reported body mass index (BMI; in kg/m2) between 18 and 40, regularly ate 3 meals/d, and reported liking and being willing to eat all 3 foods to be served in the test meal. Potential participants were excluded from participation if they were dieting to gain or lose weight, had food allergies or restrictions, were taking medications known to affect appetite, were smokers, were athletes in training, or were pregnant or breastfeeding.

After the initial telephone interview, potential participants came to the laboratory to complete several questionnaires, including the Zung Self-Rating Scale (21), which assesses symptoms of depression; the short form of the Eating Attitudes Test (22), which evaluates disordered attitudes toward food; and the Eating Inventory (23), which assesses dietary restraint, disinhibition, and tendency toward hunger. During the screening appointment, potential participants rated the taste of 6 samples of foods, including the 3 foods to be served at the test meal. The taste of each food was rated on a 100-mm visual analog scale with a left anchor of “not at all pleasant” and a right anchor of “extremely pleasant.” Also, individuals had their height and weight measured without shoes and coats. Potential participants were not enrolled in the study if they scored >41 on the Zung Self-Rating Scale or >20 on the Eating Attitudes Test, had a measured BMI <18 or >40, or rated the taste of any of the study foods <30 mm.

The sample size for each experiment was estimated by using data from previous single-meal studies in the laboratory. The minimum clinically significant difference in meal energy intake was assumed to be 30 kcal for each increase in vegetable portion size and 30 kcal for the decrease in vegetable energy density. A power analysis was performed by using an approximation technique on the basis of the noncentral F distribution and an exemplary data set analyzed with a linear mixed model (24). It was estimated that a sample of 22 women and 22 men in each study would allow the detection of this difference in meal energy intake with >80% power by using a 2-sided test with a significance level of 0.05.

Fifty-two participants were enrolled in the addition study, and 48 participants were enrolled in the substitution study. Three participants were excluded from the addition study for failure to arrive for scheduled meals. Thus, 49 participants completed the addition study, and 48 participants completed the substitution study. Participant characteristics are shown in Table 1. In the addition study, 29 participants were normal weight, 19 participants were overweight, and 1 participant was obese; in the substitution study, 31 participants were normal weight, 15 participants were overweight, and 2 participants were obese.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of participants in the 2 studies1

| Addition study |

Substitution study |

|||

| Characteristic | Women (n = 24) | Men (n = 25) | Women (n = 24) | Men (n = 24) |

| Age (y) | 26.7 ± 1.6 | 26.8 ± 1.2 | 28.5 ± 1.5 | 24.8 ± 1.3 |

| Height (m) | 1.67 ± 0.012 | 1.77 ± 0.023 | 1.63 ± 0.01 | 1.81 ± 0.023 |

| Weight (kg) | 64.5 ± 1.9 | 78.5 ± 2.53 | 61.6 ± 2.3 | 78.9 ± 1.93 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.2 ± 0.6 | 25.0 ± 0.64 | 23.0 ± 0.7 | 24.1 ± 0.5 |

| Energy expenditure (kcal/d)5 | 2227 ± 33 | 2835 ± 493 | 2161 ± 42 | 2887 ± 363 |

| Dietary restraint score6 | 6.8 ± 0.6 | 7.5 ± 0.8 | 8.0 ± 0.9 | 5.7 ± 0.9 |

| Disinhibition score6 | 5.3 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 4.0 ± 0.5 |

| Hunger score6 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 4.2 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 0.4 | 4.5 ± 0.7 |

All values are means ± SEs.

Significantly different from the substitution study, P = 0.03 (Student's t test).

Significantly different from women in the same study (Student's t test): 3P < 0.0001, 4P < 0.05.

Energy requirements were estimated from sex, age, height, weight, and activity level (25).

Score from the Eating Inventory (23).

Participants in each study gave signed informed consent to participate. The consent form stated that the purpose of the study was to investigate the perceptions of different tastes at a meal. The studies were approved by the Office for Research Protections of The Pennsylvania State University, and participants were financially compensated for their participation.

Composition of test meals

The test meal in both studies was composed of portions of vegetable, grain, and meat that were served together on a large plate (31.5 cm in diameter) accompanied by 1 L cold water as a beverage. The vegetable served at the meal was cooked broccoli (Birds Eye Foods Inc, Rochester, NY), which was varied in portion size and energy density in the same way in both studies (Table 2). The smallest portion of the vegetable (180 g) was chosen to provide approximately one-third of the daily intake of vegetables recommended for the study population (26). This portion was equivalent to ≈2.5 servings, where the volume of a serving is defined as one-half cup (118 mL). The other portions of the vegetable were determined by increasing the smallest portion by 50% (to 270 g) and by 100% (to 360 g). For comparison, the mean amount of broccoli consumed per eating occasion in this age group in a nationally representative sample was 134 g (27). The broccoli was served in 2 versions that differed in energy density but were matched in palatability. The 0.8-kcal/g version was flavored with a moderate amount of butter (Land O'Lakes Inc, Arden Hills, MN) and salt, and the 0.4-kcal/g version was flavored with light butter (Land O'Lakes Inc) and butter flavoring (Alberto-Culver USA, Melrose Park, IL). The grain served at the meal was rice pilaf (Mars Incorporated, Vernon, CA), and the meat was beef pot roast (Hormel Food Sales LLC, Austin, MN). The grain and meat components were not varied in energy density, and both components had an energy density of 1.5 kcal/g.

TABLE 2.

Composition of test meals served in the 2 studies in which portion size (in g) and energy density (in kcal/g) of the vegetable were varied

| Vegetable portion size and energy density |

||||||

| 180 g |

270 g |

360 g |

||||

| 0.4 kcal/g | 0.8 kcal/g | 0.4 kcal/g | 0.8 kcal/g | 0.4 kcal/g | 0.8 kcal/g | |

| Addition study (n = 49)1 | ||||||

| Vegetable energy served (kcal) | 81 | 149 | 121 | 223 | 162 | 298 |

| Grain portion size (g) | 326 | 326 | 326 | 326 | 326 | 326 |

| Grain energy served (kcal) | 504 | 504 | 504 | 504 | 504 | 504 |

| Meat portion size (g) | 281 | 281 | 281 | 281 | 281 | 281 |

| Meat energy served (kcal) | 422 | 422 | 422 | 422 | 422 | 422 |

| Total meal size (g) | 786 | 786 | 875 | 875 | 965 | 965 |

| Total meal energy served (kcal) | 1007 | 1075 | 1047 | 1150 | 1088 | 1225 |

| Substitution study (n = 48)2 | ||||||

| Vegetable energy served (kcal) | 81 | 149 | 121 | 223 | 162 | 298 |

| Grain portion size (g) | 326 | 326 | 272 | 272 | 217 | 217 |

| Grain energy served (kcal) | 504 | 504 | 420 | 420 | 335 | 335 |

| Meat portion size (g) | 281 | 281 | 234 | 234 | 187 | 187 |

| Meat energy served (kcal) | 422 | 422 | 351 | 351 | 281 | 281 |

| Total meal size (g) | 786 | 786 | 774 | 774 | 762 | 762 |

| Total meal energy served (kcal) | 1007 | 1075 | 893 | 996 | 778 | 915 |

In the addition study, more of the vegetable was added to the grain and meat components of the meal.

In the substitution study, more of the vegetable was substituted for the grain and meat components on the basis of volume.

The portion sizes of the grain and meat components differed in the 2 studies (Table 2). In the addition study, equal amounts of the grain and meat on the basis of volume were served in all test meals (1.8 cups each), so that as the portion of the vegetable was increased, the total volume and energy content of food served at the meal increased. In the substitution study, as the portion of the vegetable was increased, the amounts of the grain and meat were decreased (from 1.8 to 1.5 to 1.2 cups each), so that the total volume of food served at the meal did not change. Thus, the proportion of the vegetable was increased from 25% to 38 or 50% of the plate, and the proportions of the grain and meat were each decreased from 38% to 31 or 25% of the plate. As the vegetable was substituted for the more energy-dense grain and meat, the total energy served at the meal decreased.

Daily procedures and data collection

In both studies, each participant was tested on the same weekday, with ≥1 wk between test days. On the day before each test day, participants were instructed to keep their evening meal and their physical activity level consistent and to refrain from drinking alcoholic beverages during the evening. To encourage compliance with this protocol, participants kept a brief record of their food and beverage intake and activity on the day before each test day. On test days, participants came to the laboratory at scheduled times to eat breakfast (which was not varied across test days) and the test lunch; the interval between breakfast and lunch was ≥3 h. Participants were instructed not to consume any foods or beverages, other than water, between breakfast and lunch and not to drink any water during the hour before lunch. Before being served breakfast, participants were given a brief questionnaire that asked whether they had consumed any foods or beverages since waking, had taken any medications, or had felt ill. A similar questionnaire was completed before lunch. If participants felt ill or did not comply with the study protocol, their test day was rescheduled.

During all meals, participants were seated in private booths and were instructed to consume as much of the foods and beverages as they wanted. At lunch, participants were asked not to mix the 3 foods on the plate. All food items were weighed before and after meals to determine the amount consumed to within 0.1 g. Energy and macronutrient intakes were calculated by using information from food manufacturers and a standard food-composition database (28).

Participants rated their hunger, fullness, and prospective consumption (how much they thought they could eat) immediately before and after each meal by using visual analog scales. For example, participants answered the question “How hungry are you right now?” by marking a 100-mm line that was anchored on the left with “Not at all hungry” and on the right with “Extremely hungry.” Participants also rated the characteristics of the test foods before and after the lunch meal; they were given a small sample of each food and used 100-mm scales to rate the pleasantness of the taste and texture (anchored by “Extremely pleasant” and “Not at all pleasant”). After participants were served the test meal but before they began eating, they rated the serving size of each food and the entire meal compared with their usual portion (anchored by “A lot smaller” and “A lot larger”) and their perception of the amount of calories and fat in the meal [anchored by “No calories (fat) at all” and “Extremely high in calories (fat)”].

On the final test day, participants completed a discharge questionnaire after lunch in which they ranked their preference for the 3 foods served at the test meal from most favorite to least favorite. Participants were also asked their opinion of the purpose of the study and whether they noticed any differences between the sessions.

Statistical analyses

Data in each study were analyzed by using a mixed linear model with repeated measures (SAS 9.1; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). The fixed factors in the model were vegetable portion size, vegetable energy density, study week, and participant sex; the factor of food preference was also examined. Interactions of factors were tested for significance before examining their main effects. The main outcomes analyzed were food intake (g) and energy intake (kcal) for each food and for the entire meal as well as overall energy density of the meal (kcal/g). The meal energy density was calculated on the basis of food intake only, excluding beverage intake (29). The secondary outcomes were ratings of hunger and satiety and ratings of food characteristics; the ratings of hunger and satiety measured after the meal were adjusted by including the before-meal rating as a covariate in the model. For multiple comparisons between means, the significance level was adjusted by using a simulated distribution (24).

Predefined comparisons were made between the studies by using a similar mixed linear model on the combined data with the addition of a between-subjects factor. Differences in food intake (weight), energy intake, and energy density of the entire meal were examined according to the vegetable portion size, vegetable energy density, and study. Thus, the analysis provided a direct comparison of the effects of the addition and substitution strategies when the vegetable was served in the same amounts and energy densities but the portion sizes of the grain and meat differed.

To determine whether the effects of portion size on intake were attributable to any limitation in the amount of available food, participants were identified who consumed >95% of the smallest amount that was served of each of the 3 meal components. The influence of these groups of participants on the outcomes of vegetable intake and meal energy intake was examined.

Analysis of covariance was used to examine the influence of participant characteristics (such as age and BMI) on the relation between the experimental factors and main outcomes. The primary predictors of each main outcome were identified by evaluating the proportion of variability in the mixed linear model that was explained by the experimental factors and participant characteristics (30). The daily energy requirements of participants were estimated from their sex, age, height, weight, and activity level (25). Differences between the characteristics of women and men were examined by using t tests. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05 and are reported as means ± SEs.

RESULTS

Effects on food intake

Increasing the portion size of the vegetable led to a significant increase in vegetable consumption, which did not differ significantly between the 2 experiments (P < 0.0001; Table 3). Increasing the portion of the vegetable from 180 to 270 g increased vegetable intake in both studies by a mean (±SE) of 34 ± 4 g, equivalent to about half a serving. This amount represented an increase in vegetable consumption of 29 ± 4%. Doubling the portion of the vegetable from 180 to 360 g increased vegetable intake by 60 ± 5 g (49 ± 4%), equivalent to about three-quarters of a serving. Although vegetable intake increased as the portion size was increased, there was a significant decrease in intake as a proportion of the amount served from 72 ± 2% to 61 ± 2% to 53 ± 2% (P < 0.0001). The effects of vegetable portion size on vegetable consumption were independent of the effects of vegetable energy density. Reducing the energy density of the vegetable led to a small but significant decrease in vegetable consumption (9 ± 3 g; P = 0.002).

TABLE 3.

Food and energy intakes at test meals served in the 2 studies in which portion size (in g) and energy density (in kcal/g) of the vegetable were varied1

| Vegetable portion size and energy density |

|||||||||

| 180 g |

270 g |

360 g |

P values |

||||||

| 0.4 kcal/g | 0.8 kcal/g | 0.4 kcal/g | 0.8 kcal/g | 0.4 kcal/g | 0.8 kcal/g | Portion-size effect2 | Energy-density effect3 | Differences between studies4 | |

| Addition study (n = 49)5 | |||||||||

| Vegetable intake (g) | 121 ± 8 | 127 ± 7 | 149 ± 10 | 160 ± 10 | 173 ± 12 | 189 ± 13 | <0.0001 | 0.007 | NS |

| Grain intake (g) | 187 ± 12 | 183 ± 13 | 172 ± 13 | 179 ± 12 | 190 ± 13 | 173 ± 13 | NS | NS | Portion-size effect (0.024) |

| Meat intake (g) | 141 ± 10 | 136 ± 10 | 139 ± 10 | 138 ± 10 | 134 ± 10 | 138 ± 10 | NS | NS | Portion-size effect (0.004) |

| Total meal intake (g) | 449 ± 25 | 446 ± 24 | 460 ± 28 | 477 ± 26 | 498 ± 28 | 499 ± 30 | 0.0002 | NS | Portion-size effect (0.033) |

| Total meal energy intake (kcal) | 555 ± 32 | 592 ± 34 | 541 ± 35 | 616 ± 35 | 574 ± 34 | 631 ± 38 | NS | <0.0001 | Portion-size effect (0.009) |

| Total meal energy density (kcal/g) | 1.23 ± 0.01 | 1.32 ± 0.01 | 1.17 ± 0.02 | 1.29 ± 0.01 | 1.16 ± 0.02 | 1.26 ± 0.01 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | Portion-size effect (0.011) Energy-density effect (0.003) |

| Substitution study (n = 48)6 | |||||||||

| Vegetable intake (g) | 133 ± 7 | 134 ± 7 | 168 ± 11 | 173 ± 11 | 190 ± 12 | 205 ± 13 | <0.0001 | NS | — |

| Grain intake (g) | 154 ± 13 | 142 ± 12 | 128 ± 11 | 121 ± 10 | 121 ± 9 | 118 ± 9 | <0.0001 | NS | — |

| Meat intake (g) | 144 ± 8 | 147 ± 7 | 130 ± 6 | 124 ± 7 | 128 ± 6 | 122 ± 6 | <0.0001 | NS | — |

| Total meal intake (g) | 431 ± 20 | 423 ± 19 | 425 ± 21 | 418 ± 21 | 439 ± 19 | 446 ± 20 | NS | NS | — |

| Total meal energy intake (kcal) | 514 ± 27 | 552 ± 26 | 469 ± 24 | 517 ± 26 | 466 ± 22 | 537 ± 24 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | — |

| Total meal energy density (kcal/g) | 1.18 ± 0.02 | 1.30 ± 0.01 | 1.10 ± 0.02 | 1.24 ± 0.02 | 1.06 ± 0.02 | 1.21 ± 0.02 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | — |

All values are means ± SEs.

Significance of effects of vegetable portion size as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures. All effects were independent of vegetable energy density.

Significance of effects of vegetable energy density as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures. All effects were independent of vegetable portion size.

Significance of differences between the addition study and the substitution study in the effects of vegetable portion size and vegetable energy density as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures.

In the addition study, more of the vegetable was added to the grain and meat components of the meal.

In the substitution study, more of the vegetable was substituted for the grain and meat components on the basis of volume.

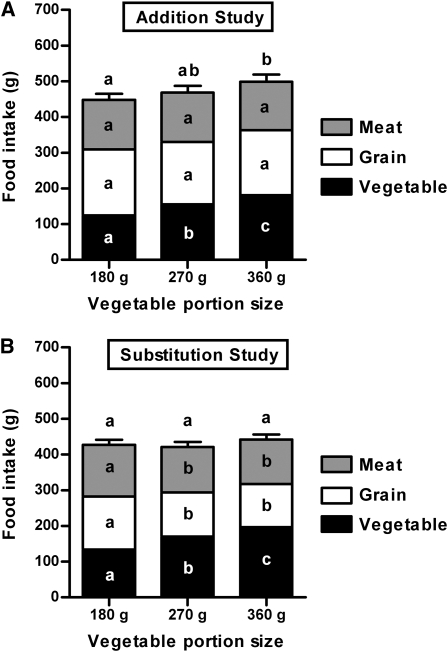

The effects on intake of the meat and grain, as well as on the total weight of food consumed at the meal, differed between the 2 studies (P < 0.033; Figure 1). In the addition study, in which the portions of the meat and grain were not varied, intake of the meat and grain did not differ as the vegetable portion size was increased. Thus, when more of the vegetable was added to the other meal components, the total weight of food consumed at the meal increased (P = 0.0002; Figure 1A). In the substitution study, in which portions of the meat and grain were decreased, intakes of the meat and grain decreased as the portion of the vegetable was increased from 180 to 270 g (P < 0.0001; Figure 1B). There was no further decrease in meat and grain intake as the vegetable portion was increased to 360 g; in this condition, intake as a proportion of the amount served increased for the meat (from 53 ± 2% to 67 ± 2%) and grain (from 46 ± 3% to 55 ± 3%). Thus, when the vegetable was substituted for the other meal components, the total weight of food consumed at the meal did not differ significantly.

FIGURE 1.

Mean (±SE) weight of food consumed according to the portion size of the vegetable served in the addition study (A; n = 49), in which the extra vegetable was added to other meal components, and the substitution study (B; n = 48), in which the extra vegetable was substituted for other meal components. The effects of vegetable portion size were independent of the effects of vegetable energy density in both studies; thus, the values are shown for both energy densities combined. Within each meal component, values with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.0002) as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures.

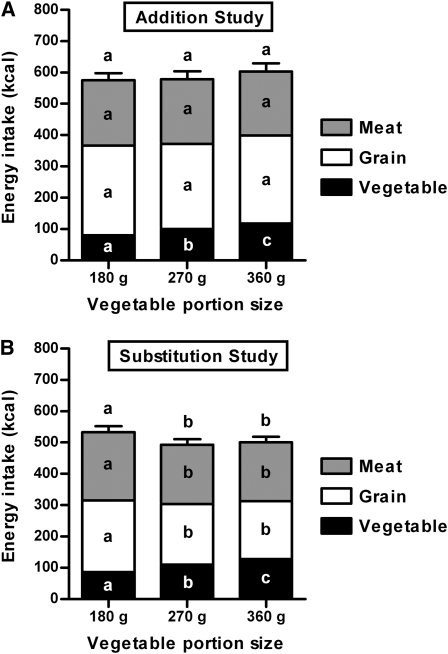

Effects on energy intake

The effects of vegetable portion size on energy intake of each meal component and the entire meal differed significantly depending on whether the portions of the meat and grain were unchanged, as in the addition study, or were decreased, as in the substitution study (P = 0.009; Figure 2). In the addition study, although increasing the portion size of the vegetable led to a small but significant increase in energy intake from the vegetable (P < 0.0001), there was no significant change in energy intake from the meat and grain and no significant difference in total energy intake at the meal (Figure 2A). In the substitution study, increasing the portion size of the vegetable also led to a small but significant increase in energy intake from the vegetable (P < 0.0001). However, there was a significant decrease in energy intake from the more energy-dense meat and grain as their portion sizes were decreased (P < 0.0001; Figure 2B). Thus, as the portion of the vegetable was increased from 180 to 270 g, total energy intake at the meal decreased by 40 ± 10 kcal (7 ± 2%); there was no further decrease as the vegetable portion was increased from 270 to 360 g.

FIGURE 2.

Mean (±SE) energy intake according to the portion size of the vegetable served in the addition study (A; n = 49), in which the extra vegetable was added to other meal components, and the substitution study (B; n = 48), in which the extra vegetable was substituted for other meal components. The effects of vegetable portion size were independent of the effects of vegetable energy density in both studies; thus, the values are shown for both energy densities combined. Within each meal component, values with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.0007) as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures.

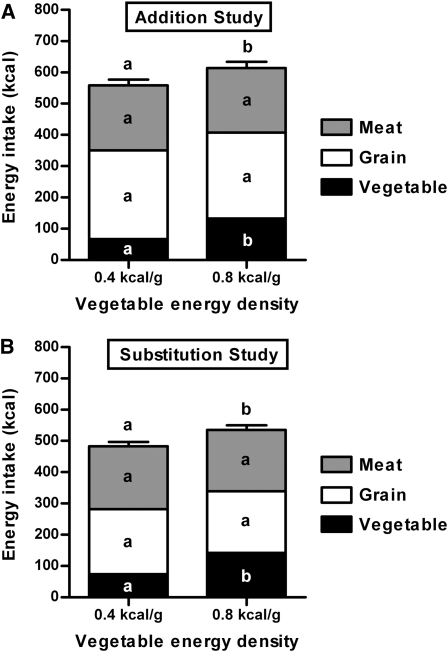

The effects of decreasing the energy density of the vegetable on energy intake did not differ between the studies; reducing the vegetable energy density from 0.8 to 0.4 kcal/g significantly decreased the energy intake of the vegetable and the entire meal (P < 0.0001; Figure 3). The reduction in the energy density of the vegetable led to a decrease in meal energy intake of 55 ± 9 kcal, equivalent to 8 ± 2% of meal energy intake. The effect of reducing the vegetable energy density was independent of the effect of portion size; thus, these effects added together to influence energy intake. In the substitution study, the combined effects of reducing the energy density of the vegetable and increasing the portion size of the vegetable from 180 to 270 g resulted in a decrease in meal energy intake of 83 ± 15 kcal (14 ± 3%).

FIGURE 3.

Mean (±SE) energy intake according to the energy density of the vegetable served in the addition study (A; n = 49) and the substitution study (B; n = 48). The effects of vegetable energy density were independent of the effects of vegetable portion size in both studies; thus, the values are shown for all 3 portions combined. Within each meal component, values with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.0001) as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures.

In the evaluation of whether the effects of portion size on intake were attributable to a limitation in the amount of food, 19 of the 97 participants in both studies were identified who consumed >95% of the smallest amount of the vegetable that was served. The effects of vegetable portion size on vegetable intake and meal energy intake did not differ significantly between participants who did and did not consume 95% of the smallest portion of the vegetable. Similarly, there were 11 participants who consumed >95% of the smallest amount of the grain served, and 7 participants who consumed >95% of the smallest amount of the meat served. The effects of portion size on meal energy intake were not significantly different in participants who did and who did not consume >95% of the smallest portion of the grain or meat. Thus, there was no evidence that the influence of portion size on intake was attributable either to a limitation in the size of the smallest portion of the vegetable or to a limitation in the amount of the grain or meat when the largest portion of the vegetable was served.

Effects on energy density of the meal

In both studies, the overall energy density that was consumed at the meal was significantly decreased by increasing the portion size of the vegetable and was independently decreased by reducing the energy density of the vegetable (all P < 0.0001). However, the magnitude of these effects was significantly different in the 2 studies (P < 0.01; Table 3). The increase in vegetable portion size and the decrease in vegetable energy density led to greater reductions in the meal energy density when the vegetable was substituted for other meal components (substitution study) than when the vegetable was added to the meal (addition study).

Ratings of hunger, satiety, and food characteristics

There were no significant differences between the addition and substitution studies in the effects on ratings of hunger, prospective consumption, and fullness after meals; these ratings did not differ significantly by either the vegetable portion size or energy density (data not shown). Thus, the reductions in energy intake from substituting more of the vegetable and from reducing the vegetable energy density did not lead to increased hunger or decreased fullness.

In both studies, ratings of the serving size of the vegetable (compared with the participant's usual portion) differed significantly for each vegetable portion size served (P < 0.0001; Table 4). The effects on ratings of the size and calorie content of the entire meal differed between the studies (Table 4). In the addition study, these ratings did not differ across conditions, although the meal increased in size and energy as the vegetable portion was increased. In the substitution study, these ratings decreased significantly as the vegetable was substituted for the grain and meat (P < 0.04). Therefore, participant ratings of the size and calorie content of the meal reflected the portion sizes of the grain and meat.

TABLE 4.

Ratings of food and meal characteristics according to portion size of the vegetable served in the 2 studies1

| Addition study (n = 49) |

Substitution study (n = 48) |

|||||||

| 180-g portion | 270-g portion | 360-g portion | P2 | 180-g portion | 270-g portion | 360-g portion | P | |

| Vegetable serving size3 | 69.7 ± 1.7a | 78.6 ± 1.6b | 83.8 ± 1.3c | <0.0001 | 64.4 ± 1.7a | 73.7 ± 1.6b | 83.6 ± 1.7c | <0.0001 |

| Grain serving size3 | 76.9 ± 1.4a | 76.2 ± 1.5a | 73.2 ± 1.5b | 0.01 | 79.3 ± 1.5a | 70.5 ± 1.7b | 62.0 ± 1.4c | <0.0001 |

| Meat serving size3 | 71.1 ± 1.6 | 72.7 ± 1.6 | 73.0 ± 1.6 | NS | 72.5 ± 1.5a | 68.3 ± 1.7b | 59.0 ± 1.8c | <0.0001 |

| Meal size | 79.0 ± 1.3 | 80.8 ± 1.4 | 81.4 ± 1.3 | NS | 79.7 ± 1.4a | 76.7 ± 1.6b | 76.5 ± 1.6b | 0.04 |

| Meal calories | 63.6 ± 1.8 | 64.7 ± 1.7 | 64.6 ± 1.8 | NS | 63.6 ± 1.6a | 61.4 ± 1.6a | 57.5 ± 1.5b | 0.0005 |

| Meal fat | 54.3 ± 2.2 | 55.3 ± 2.3 | 53.5 ± 2.2 | NS | 51.1 ± 2.1a | 50.2 ± 1.9a | 46.2 ± 1.9b | 0.008 |

All values are mean ± SE ratings derived from 100-mm visual analog scales. For each rating within a given study, values with different superscript letters are significantly different as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures. None of the ratings differed significantly by vegetable energy density; thus, results are reported for both energy densities combined.

Significance of the portion-size effect as assessed by a mixed linear model with repeated measures.

Participants rated the serving size as compared with their usual portion of that food.

Ratings taken before meals of the pleasantness of taste and texture of the vegetable did not differ significantly by vegetable portion size or energy density in either study. The rating of taste for the 0.8 kcal/g version of the vegetable was 67.6 ± 1.1 and for the 0.4 kcal/g version was 66.8 ± 1.2. Thus, although the vegetable was varied in energy density by using products that differed in butter content, participants did not rate the 2 versions as significantly different in pleasantness of taste. In both studies, the meat component of the meal was rated significantly higher in pleasantness of taste across all conditions than the pleasantness of taste of either the vegetable or grain (both P < 0.0001). The rating of taste for the meat was 73.6 ± 0.7, and the rating of taste for the grain was 65.3 ± 0.7.

Predictors of food intake, energy density, and energy intake at the meal

The main predictors of the total weight of food consumed at the meal were the participant factors of estimated energy expenditure and taste ratings of the grain and vegetable followed by the experimental factors of the portion sizes of the vegetable and meat. Together, these variables accounted for 28% of the variability in total food intake. For the overall energy density consumed at the meal, the main predictors were the experimental factors of the energy density of the vegetable and the portion sizes of the meat and vegetable followed by the participant taste ratings for the grain (positive relation) and vegetable (negative relation). Together, these factors accounted for 40% of the variability in meal energy density. As expected by the mathematical relation, the variability in total energy intake at the meal was completely accounted for by the weight and energy density of the food consumed. Therefore, the predictors of total energy intake at the meal reflected those for meal weight and energy density: participant estimated energy expenditure, taste ratings of the grain, portion sizes of the meat and vegetable, and vegetable energy density; together, these factors accounted for 33% of the variability in meal energy intake.

Influence of participant characteristics

In both studies, analysis of covariance showed that the relation between the experimental factors (vegetable portion size and vegetable energy density) and the outcomes of food and energy intakes was not significantly affected by participant sex, race, ethnicity, age, height, weight, and BMI or scores for restraint, disinhibition, tendency to hunger, depression, or disordered eating.

In the addition study, the vegetable was reported to be the preferred food by 14 participants (29%), the grain was reported to be the preferred food by 15 participants (31%), and the meat was reported to be the preferred food by 20 participants (41%). In the substitution study, these numbers were 25 (52%), 6 (13%), and 17 (35%), respectively. There was no significant influence of food preference on the response to vegetable portion size in either study; participants consumed more of the vegetable as the portion size of the vegetable was increased, whether they preferred the vegetable, the grain, or the meat. However, in the group of participants who preferred the vegetable, vegetable intake was significantly greater, and meal energy density was significantly lower, than in the group of participants who preferred the grain or meat (all P < 0.0001; data not shown).

On the discharge questionnaire in the addition study, 22 participants (45%) noted that some portion sizes changed across the weeks. In the substitution study, 41 participants (85%) noted some change in portion sizes, most often of the vegetable. Only 13 participants (27%) in the addition study and 8 participants (17%) in the substitution study correctly stated that a purpose of the study was to examine the influence of portion size on intake. The effects of the experimental variables on meal energy intake did not differ significantly between participants who did and did not correctly determine the study purpose in either experiment.

DISCUSSION

The results of these experiments showed that increasing the portion size of the vegetable served at a meal, either by substituting the vegetable for other meal components or simply by adding more of the vegetable, led to a significantly greater consumption of the vegetable. To our knowledge, these are the first experiments in adults indicating that serving larger portions can be used strategically to increase the intake of nutrient-rich foods that are low in energy density, such as vegetables. Furthermore, increasing the portion size of the vegetable led to a reduction in energy intake at the meal but only when the amounts of the other foods on the plate were decreased proportionately. Reducing the energy density of the vegetable resulted in a decrease in meal energy intake that was independent of changes in portion sizes of the meal components. These results showed that substituting extra vegetables for more energy-dense foods can reduce meal energy intake, and this strategy is more effective than simply adding vegetables to the meal.

In a previous study (16) in which the portions of all foods were increased by 50% for 11 d, vegetable intake was not significantly affected by the increase in portion size. This contrasts with the current experiments, in which increasing the portion of the vegetable without increasing the portions of the other foods led to enhanced vegetable consumption. We showed that serving 50% more of the vegetable increased vegetable intake ≈30%, or by one-half serving. Moreover, the effect of portion size on vegetable intake continued across the range of portions served, even though the smallest portion was larger than the average amount consumed at a meal (27). These findings suggest that the influence of increasing the portion size of vegetables on vegetable intake depends on the amount of competing foods available. However, serving larger portions of the vegetable led to a greater proportion of the vegetable remaining uneaten, which has implications for cost and waste. Food providers should be encouraged to find the optimal balance between increased intake and wastage when implementing this strategy.

Although these experiments showed that adding more of the vegetable to a meal and substituting the vegetable for other meal components led to similar increases in vegetable intake, the 2 strategies had different effects on energy intake. Adding more vegetable without changing the portion sizes of the grain and meat increased the total weight of food consumed at the meal and decreased the overall energy density of the meal. Because these 2 changes had opposite influences on energy intake, the net effect was that meal energy intake did not differ significantly. This finding is similar to that of a previous study (31) in which vegetables were added to a meal by increasing the portion size of a salad served as a preload. When the salad was low in energy density (0.33 or 0.67 kcal/g), increasing the portion size did not significantly affect meal energy intake. However, when the salad was higher in energy density (1.33 kcal/g), increasing the portion size led to an increase in meal energy intake. Thus, it is possible that the energy intake at a meal may be increased by adding extra vegetables that are relatively high in energy density, such as vegetables that are fried or served with sauce or dressing. If vegetables are added to a meal without changing the amounts of the other foods, the best strategy to enhance satiety and maintain meal energy intake is to ensure that they are low in energy density.

When the goal is to decrease energy intake, the current results indicate that substituting vegetables for more energy-dense meal components has a greater effect than simply adding more vegetables. Increasing the vegetable portion size by substitution reduced the energy density of the meal without increasing the weight of food consumed, resulting in a decrease in energy intake of 40 kcal or 7%. The substitution strategy was previously tested by increasing the proportion of vegetables in mixed dishes such as casseroles to decrease the energy density (11, 13, 19). When vegetables were substituted for other ingredients without influencing palatability, subjects ate a consistent weight of food so that energy intake decreased in parallel with the reduction in energy density (11).The results presented in the current study show that substituting vegetables for more energy-dense foods also reduced energy intake when the foods were served separately and individuals could choose the amount of each food to consume. Participant preference for the vegetable, grain, or meat did not significantly affect participant response to an increase in vegetable portion size. However, a requirement for participation in the experiments was a liking of all 3 foods. The challenge in future research will be to develop strategies to increase vegetable consumption in people with a low preference.

The results of the current experiments reinforce previous findings showing that reducing the energy density of foods significantly decreases meal energy intake and that this effect is independent of changes in portion size (19, 20). We showed that reducing vegetable energy density from 0.8 to 0.4 kcal/g resulted in a decrease in meal energy intake of 55 kcal or 8%. Because the effects of energy density and portion size were independent, they added together to determine energy intake at the meal. In the substitution study, when the amount of the vegetable was decreased in energy density and simultaneously increased in portion size by 50%, these effects combined to reduce meal energy intake by 83 kcal or 14%.

The relations between portion size, energy density, and intake are probably dependent on the relative palatability of available foods. In a previous study (16), the effect of portion size on intake was shown to be greater for foods that were higher in energy density. Because such foods are generally more palatable than those lower in energy density (32, 33), it is likely that differences in palatability played a role in this result. In the current experiments, we reduced the energy density of the vegetable while keeping its palatability relatively constant, as indicated by participants' ratings of taste. When palatability was matched across the 2 levels of energy density, increasing the portion size of the vegetable increased its intake to a similar extent. Thus, serving larger portions can be used as a strategy to increase the consumption of vegetables, even if they are low in energy density, as long as the vegetables are sufficiently palatable. However, it is important to ensure that palatability is not enhanced simply by adding high-energy-dense sauces and flavorings because this is likely to lead to an increase in meal energy intake.

The complex relations between the portion size, energy density, and palatability of vegetables and their effects on energy intake could explain the inconsistent results from studies of vegetable and fruit intake and body weight. Several intervention trials reported that adding vegetables and fruits to the diet was associated with no change in body weight (34) or weight gain (35). However, in these trials there was no explicit advice on incorporating the added produce into the diet; participants could have added high-energy-dense options such as fried items or those with high-fat sauces. In contrast, data from several clinical interventions (4, 5, 36, 37) indicate that specific advice to increase the intake of vegetables and fruits that are low in energy density was associated with weight loss. These inconsistencies emphasize the need for more systematic studies to formulate effective strategies for the incorporation of vegetables and fruits into the diet to enhance satiety, reduce energy intake, and facilitate weight management. The long-term acceptability and sustainability of these strategies need to be evaluated along with the individual characteristics that could influence responses.

Simple and effective advice is needed that encourages individuals to optimize their diets for nutritional and energy balance. The results of the current experiments suggest that an emphasis on increasing the proportion of vegetables on the plate is likely to promote the consumption of vegetables. In addition, the results support the current advice from government agencies that emphasizes the importance of substituting vegetables for higher-energy foods to avoid excessive energy intake (17, 18).

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of the staff and students in the Laboratory for the Study of Human Ingestive Behavior at The Pennsylvania State University.

The authors' responsibilities were as follows—BJR, LSR, and JSM: study design, interpretation of the data, and critical revision of the manuscript; JSM: supervision of data collection; LSR: statistical analysis; and BJR and LSR: writing of the manuscript. BJR is the author of The Volumetrics Weight-Control Plan (HarperTorch, 2003) and The Volumetrics Eating Plan (HarperCollins, 2007). None of the authors had a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guenther PM, Dodd KW, Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Most Americans eat much less than recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables. J Am Diet Assoc 2006;106:1371–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanck HM, Gillespie C, Kimmons JE, Seymour JD, Serdula MK. Trends in fruit and vegetable consumption among U.S. men and women, 1994–2005. Prev Chronic Dis 2008;5. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2008/apr/07_0049.htm (cited 5 October 2009) [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Agriculture Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005. January 2005. Available from: http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/report/ (cited 5 October 2009)

- 4.Rolls BJ, Ello-Martin JA, Tohill BC. What can intervention studies tell us about the relationship between fruit and vegetable consumption and weight management? Nutr Rev 2004;62:1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ello-Martin JA, Roe LS, Ledikwe JH, Beach AM, Rolls BJ. Dietary energy density in the treatment of obesity: a year-long trial comparing 2 weight-loss diets. Am J Clin Nutr 2007;85:1465–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buijsse B, Feskens EJ, Schulze MB, et al. Fruit and vegetable intakes and subsequent changes in body weight in European populations: results from the project on Diet, Obesity, and Genes (DiOGenes). Am J Clin Nutr 2009;90:202–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camelon KM, Hadell K, Jamsen PT, et al. The Plate Model: a visual method of teaching meal planning. J Am Diet Assoc 1998;98:1155–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prince JR. Why all the fuss about portion size?: Designing the New American Plate. Nutr Today 2004;39:59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UK Food Standards Agency The eatwell plate. 2007. Available from: http://www.food.gov.uk/healthiereating/eatwellplate (cited 5 October 2009)

- 10.Tikkanen I, Urho U-M. Free school meals, the plate model and food choices in Finland. Br Food J 2009;111:102–19 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bell EA, Castellanos VH, Pelkman CL, Thorwart ML, Rolls BJ. Energy density of foods affects energy intake in normal-weight women. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;67:412–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rolls BJ, Bell EA, Castellanos VH, Pelkman CL, Chow M, Thorwart ML. Energy density but not fat content of foods affected energy intake in lean and obese women. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:863–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bell EA, Rolls BJ. Energy density of foods affects energy intake across multiple levels of fat content in lean and obese women. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;73:1010–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rolls BJ, Morris EL, Roe LS. Portion size of food affects energy intake in normal-weight and overweight men and women. Am J Clin Nutr 2002;76:1207–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diliberti N, Bordi PL, Conklin MT, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Increased portion size leads to increased energy intake in a restaurant meal. Obes Res 2004;12:562–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. The effect of large portion sizes on energy intake is sustained for 11 days. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:1535–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention How to use fruits and vegetables to help manage your weight. 2005. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/healthy_eating/fruits_vegetables.html (cited 5 October 2009)

- 18.US Department of Health and Human Services, US Department of Agriculture Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2005. 6th ed.Chapter 3: Weight management Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, January 2005. Updated 9 July 2008. Available from: http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2005/document/html/chapter3.htm (cited 5 October 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kral TVE, Roe LS, Rolls BJ. Combined effects of energy density and portion size on energy intake in women. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79:962–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Reductions in portion size and energy density of foods are additive and lead to sustained decreases in energy intake over two days. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:11–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zung WWK. Zung self-rating depression scale and depression status inventory: Sartorius N, Ban TA. Assessment of depression Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 1986:221–31 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garner DM, Olsted MP, Bohr Y, Garfinkel PE. The Eating Attitudes Test: psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychol Med 1982;12:871–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition, and hunger. J Psychosom Res 1985;29:71–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Littell RC, Milliken GA, Stroup WW, Wolfinger RD, Schabenberger O. SAS for mixed models. 2nd ed.Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.US Department of Agriculture. MyPyramid. How many vegetables are needed daily or weekly? Available from : http://www.mypyramid.gov/pyramid/vegetables_amount_table.html (cited 5 October 2009)

- 27.US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2006. Hyattsville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2008. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes2005-2006/exam05_06.htm (cited 5 October 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, release 22: Nutrient Data Laboratory homepage. Available from: http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/ndl (cited 5 October 2009)

- 29.Ledikwe JH, Blanck HM, Kettel-Khan L, et al. Dietary energy density determined by eight calculation methods in a nationally representative United States population. J Nutr 2005;135:273–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feng Z, Diehr P, Peterson A, McLerran D. Selected statistical issues in group randomized trials. Annu Rev Public Health 2001;22:167–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Meengs JS. Salad and satiety: energy density and portion size of a first course salad affect energy intake at lunch. J Am Diet Assoc 2004;104:1570–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drewnowski A. Energy density, palatability, and satiety: implications for weight control. Nutr Rev 1998;56:347–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gibson EL, Wardle J. Energy density predicts preferences for fruit and vegetables in 4-year-old children. Appetite 2003;41:97–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whybrow S, Harrison CL, Mayer C, Stubbs RJ. Effects of added fruits and vegetables on dietary intakes and body weight in Scottish adults. Br J Nutr 2006;95:496–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Djuric Z, Poore KM, Depper JB, et al. Methods to increase fruit and vegetable intake with and without a decrease in fat intake: compliance and effects on body weight in the nutrition and breast health study. Nutr Cancer 2002;43:141–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fitzwater SL, Weinsier RL, Wooldridge NH, Birch R, Liu C, Bartolucci AA. Evaluation of long-term weight changes after a multidisciplinary weight control program. J Am Diet Assoc 1991;91:421–6, 429 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Epstein LH, Gordy CC, Raynor HA, Beddome M, Kilanowski CK, Paluch R. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake and decreasing fat and sugar intake in families at risk for childhood obesity. Obes Res 2001;9:171–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]