Abstract

Ca2+ release from intracellular stores mediated by endoplasmic reticulum membrane ryanodine receptors (RyR) plays a key role in activating and synchronizing downstream Ca2+-dependent mechanisms, in different cells varying from apoptosis to nuclear transcription and development of defensive responses. Recently discovered, atypical “non-genomic” effects mediated by estrogen receptors (ER) include rapid Ca2+ release upon estrogen exposure in conditions implicitly suggesting involvement of RyRs. In the present study, we report various levels of co-localization between RyR type 2 (RyR2) and ER type β (ERβ) in the neuronal cell line HT-22, indicating a possible functional interaction. Electrophysiological analyses revealed a significant increase in single channel ionic currents generated by mouse brain RyRs after application of the soluble monomer of the long form ERβ (ERβ1). The effect was due to a strong increase in open probability of RyR higher open channel sublevels at cytosolic [Ca2+] concentrations of 100 nM, suggesting a synergistic action of ERβ1 and Ca2+ in RyR activation, and a potential contribution to Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release rather than to basal intracellular Ca2+ concentration level at rest. This RyR/ERβ interaction has potential effects on cellular physiology, including roles of shorter ERβ isoforms and modulation of the RyR/ERβ complexes by exogenous estrogens.

INTRODUCTION

Estrogen (E2; 17β-estradiol) receptors (ERs) structurally and functionally belong to a family of nuclear receptors (NRs), which promote gene transcription in various types of cells upon activation by their natural ligands [1, 2]. Nonetheless, numerous recent studies demonstrated that ERs additionally affect various intracellular signaling pathways, often producing E2-initiated “nongenomic” cellular responses on a time scale of seconds-to-minutes, which are incompatible with substantially slower transcriptional activity, indicating the involvement of ERs in rapid intracellular signaling [3, 4]. The two ER isoforms: ERα and ERβ, show a differential involvement in systemic and cellular physiological responses to E2. Studies with knock-out (KO) animals and selective ERα/β agonists revealed that ERα is crucial for reproductive development and physiology [5] and possesses higher gene transcription activity in cellular preparations [6, 7] than ERβ, while the latter contributes to systemic effects related to injury survival and repair and intracellular signaling pathways [8-11].

The most often and obvious non-genomic effect of E2 in various types of cells is rapid intracellular Ca2+ (Ca2+i) mobilization that occurs within seconds-to-minutes after E2 exposure [12-22]. The fast kinetics of the effect and its robust nature even in experiments using membrane impermeable BSA-conjugated E2 (BSA-E2), lead to the hypothesis that ERs in the plasma membrane (PM) interact with other PM proteins and are primarily responsible for Ca2+i transients. The hypothesis is well supported by observations that removal of extracellular Ca2+ eventually attenuates E2-mediated Ca2+ influx mediated by PM L-type voltage-operated Ca2+ channels (VOCC) in hippocampal neurons [19] and pituitary cells [18], by store-operated Ca2+ channels (SOCC) in enterocytes [14] and mast cells [21] and by unidentified channels in neural serotonergic cells [17]. An opposite inhibitory effect of E2 on Ca2+ influx was also mediated by PM L-type VOCC in hippocampal neurons [23], cardiomyocytes [11] and by ATP-activated channels in sensory neurons [24]. A separate functional role of ERs in the PM (reviewed in [25, 26]) was suggested by reports describing rapid Ca2+i transients due to E2-dependent activation of PM-associated G proteins in CHO cells [27] and colonic crypts [15], and activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR) in hippocampal neurons [23] and hypothalamic astrocytes [28]. Activation of PM receptors by E2 results in production of the second messengers 1,4,5-inositol-triphosphate (IP3) [16, 22, 28], cAMP [15] or both [23, 27], leading ultimately to Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and/or modulation of extracellular Ca2+ influx by PM ion channels. Resulting Ca2+i transients are thought to integrate membrane effects of E2 and downstream genomic and non-genomic Ca2+i-dependent intracellular mechanisms [25]. Although both ER isoforms are implicated in E2-dependent PM signaling [27, 28], the ERα isoform is more often referred to as the functional receptor in the PM [18, 23, 24].

While the functional role of ER within the PM agrees with moderate expression of both ER isoforms in membrane compartments [29], the immunocytochemical and ultrastructural analysis revealed that the majority of extra-nuclear ERs are located in cytoplasmic compartments with a larger number of ERβ than ERα [29-32]. The functional role of “cytoplasmic” ERβ is not clear. Localization of ERβ in mitochondria contributed to cell survival of breast cancer MCF-7 cells upon E2 treatment under elevated ROS-generating conditions [32]. Translocation of mitochondrial ERβ to the nuclei upon E2 treatment was not observed in primary neurons and cardiomyocytes [30], indicating that cytoplasmic ERβ possibly influences intracellular signaling pathways via direct protein-protein interactions. Using high-resolution ultrastructural analysis in hippocampal neurons, most cytoplasmic ERβ was identified adjacent to mitochondria and in caveolae-like endoplasmic reticulum (E.ret) membrane structures [29]. Localization of cytoplasmic ERβ to E.ret membranes could be ideal for influencing rapid release of Ca2+ stored in the E.ret by either IP3 receptors (IP3R) or ryanodine receptors (RyR) during the activation of intracellular IP3 signaling or Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) respectively. Data on such a direct interaction of ERβ with IP3R or RyR has not been obtained so far. Previous studies on the generation of E2-evoked Ca2+i transients under extracellular Ca2+-free conditions suggest E2-dependent Ca2+ release from the E.ret [12, 16, 22, 33]. The potential alternative mechanism suggests an E2-dependent Ca2+i release from intracellular stores originating from PM signaling, indirectly involving IP3Rs by upstream activation of mGluR and/or PLC in astrocytes [16, 22] and in hippocampal neurons [23] or indirectly involving IP3Rs or RyRs through unidentified PM proteins in midbrain neurons [12] and in human monocytes [33]. The PM origination of Ca2+ release from E.ret, however, is dependent on the identification of PM-associated ERs using controlled conditions of membrane-impermeable BSA-E2 without release of contaminant membrane-permeable E2 [4, 25, 26]. In a variety of non-neuronal cancer cell lines, however, IP3 production or IP3R activation has not been observed during Ca2+i release from intracellular stores evoked by E2 (or its antagonist tamoxifen) under Ca2+-free conditions [13, 34-36], indicating the possibility of RyRs being a direct target of E2-dependent mechanisms.

Ca2+i release from intracellular stores is particularly important for nitric oxide (NO) production by eNOS through Ca2+-dependent calmodulin (CaM) and CaMKII kinase [37]. In human monocytes, NO is generated following E2-induced Ca2+i release from intracellular stores [33]. Ca2+i release preceding the generation of NO in stretch-activated cardiomyocytes experimentally modeled for pressure overload hypertension, has been directly mediated by RyRs, since both ryanodine and the store-depleting agent thapsigargin (Tg), both blocked the effect [38]. Such an NO-dependent mechanism potentially plays a role in E2-dependent neuro-, cardio- and vascular protection in ischemia-reperfusion, trauma-hemorrhage and hypertrophy models [11, 39], mediated by ERβ [8, 40]. Intracellular signaling between ERβ and RyRs might represent a fundamentally new homeostatic mechanism taking place in a variety of cells. RyR is a Ca2+-activated intracellular channel possessing a large cytoplasmic domain with a variety of regulatory sites [41, 42], some of which were potential targets of PKCq, PKCa and Erk 1/2 to facilitate E2-mediated Ca2+i release in sweat gland epithelial cells [36].

We hypothesized that in addition to upstream PM signaling, cytoplasmic ERβ can directly bind RyR to modify its gating properties. To test this hypothesis, we measured the effects of ERβ on single-channel currents of the RyRs incorporated in lipid bilayers. A number of ERβ isoforms ranging from high- to very low binding affinity for E2, are known [43]. In contrast to ERα, a stable unliganded (or “antagonist”) conformational state is more favorable for the basal long isoform ERβ1 [9]. In the unliganded state ERβ is specifically reactive towards other proteins through its hinge domain [44]. We hypothesized that unliganded ERβ can be primarily reactive towards RyRs, while E2 might exert its effect through binding to an existing RyR/ERβ complex, subsequently altering RyR channel gating properties. In the present study, using immunocytochemistry and confocal microscopy we first demonstrate that ERβ and RyR are co-expressed in various compartments of the neuronal cell line HT-22. Secondly, using single channel electrophysiology, we provide evidence for the fact that unliganded ERβ changes the pattern of single channel currents of neuronal RyRs incorporated in lipid bilayers, through an interaction between the two proteins. The existence of dynamically associated RyR/ERβ complexes detected in the present study supports the notion that Ca2+i signaling in various cell types might occur not only through modification of RyR activity by E2-activated upstream mechanisms, but through direct modulation of the RyR by ERβ.

RESULTS

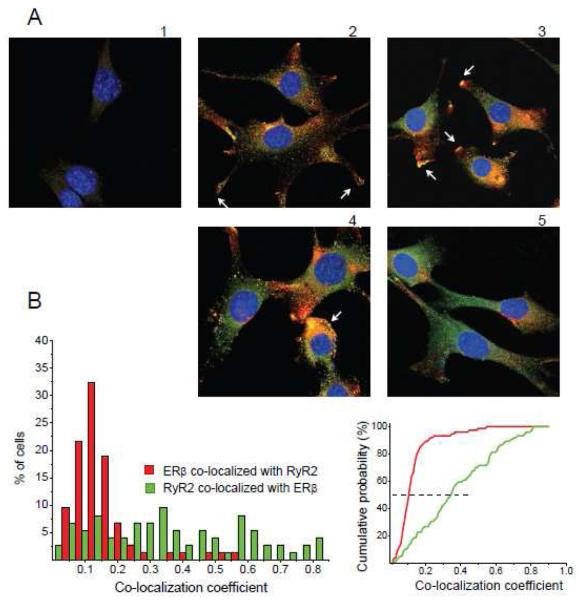

In order to obtain data regarding the interaction between RyR and ERβ, we examined co-localization patterns of both proteins in intracellular compartments in the neuronal cell line HT-22. While initially thought to be free of functional endogenous ERs [45], the HT-22 cells were found in recent studies to express both endogenous ERβ [30] and ERα [46]. Exogenously transfected ERβ1 can be detected by the PA1-310b antibody in HT-22 cells and displays a dynamic translocation into the PM after E2 treatment, while the endogenous form of ERβ (recognized by the H-150 antibody) cannot be detected by PA1-310b antibody and maintains its stable cytoplasmic intracellular distribution in HT-22 cells regardless of E2 treatment [47]. It remains to be detected if the two antibodies recognized different ERβ isoforms, or react with the same ERβ1 in different conformational or complexed states. We subsequently used the H-150 antibody that recognized the ERβ form that remains in the cytoplasm regardless of E2 application [30, 47], indicating that this form of ERβ potentially interacts with RyRs localized on intracellular membranes. Immunocytochemical confocal microscopy study using antibodies against RyR type 2 (RyR2), the most abundant neuronal and heart RyR subtype, and against ERβ (H-150) revealed that endogenous ERβ and RyR2 can be co-localized in individual HT-22 cells in various intracellular compartments (Fig. 1). The variability in co-expression patterns of the two receptors is potentially caused by differences in the cell cycle and in the functional specificity of various cellular micro-domains. The most characteristic regions of ERβ/RyR2 co-localization in individual HT-22 cells included: expanding areas of protruding neurite branches, areas morphologically resembling neuronal hillocks, unspecified regions of variable size within the cytoplasm. We also studied whether ERβ/RyR2 co-localization patterns depend on cell density and direct cell contacts (Fig. 2). We found a high variability in ERβ/RyR2 co-localization between groups as well as between individual cells within a particular group. In some cases, high levels of ERβ staining were seen proximal to the PM at the tips of growing neurites (Fig. 2 A2). More regularly co-localization of ERβ and RyR2 was observed in growing neurites and extending edges of cells (Fig. 2 A3). Both cells with- (Fig. 2 A4) and without (Fig. 2 A3) cell-cell contacts contained high levels of co-localized ERβ/RyR2 from perinuclear to peripheral regions. Some groups of HT-22 cells displayed both RyR2 and ERβ expression, but low levels of co-localization (Fig. 2 A5). For quantitative analysis, ERβ/RyR2 co-localization coefficients (CC) were calculated in 74 HT-22 cells (Fig. 2B) using standard pixel-by-pixel analysis (see Methods). In a majority of cells, from 5% to 20% of ERβ were co-localized with RyR2 (CCERβ from 0.05 to 0.2, median at CCERβ,med=0.105). The RyR2 co-localization with ERβ was more scattered among the cells, ranging from 5% to 80% (CCRyR2 from 0.05 to 0.8, median at CCRyR2,med=0.347). Co-localization analysis of RyR2 and ERβ immunoreactivities indicates that two proteins potentially interact to control Ca2+i release by RyR2 from E.ret depending on functional state and subcellular compartment of the cell. Stable, but moderate levels of co-localization for ERβ and RyR2 (10-15%) indicate that ERβ might have a variety of different, RyR-unrelated functions in the cytoplasm. On the other hand, highly variable levels of RyR co-localization with ERβ (10 to 80%) indicate that a possible functional association of RyR with ERβ is likely dynamically regulated by functional states of the cell and in subcellular compartments.

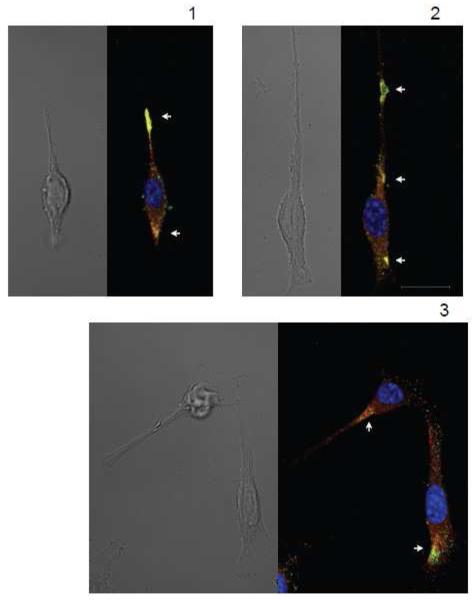

FIGURE 1. RyR2 and ERβ are co-expressed in functionally localized compartments in individual HT-22 cells.

In individual cells, both RyR2 and ERβ could be co-localized in neurite growth cones (A, top), branch protrusion points (B top), cell hillocks (A bottom and C top) and in unspecified local cytoplasmic areas (B middle and bottom, C bottom). Scale: 20 μm in panel C for all panels.

FIGURE 2. The RyR2 and ERβ co-expression pattern is highly variable in HT-22 cells.

A, In HT-22 cells with cell-cell contacts, ERβ perimembrane localization could be found in tips of growing processes (2), high level of RyR2/ERβ co-localization was characteristic for growing edges (3) and large cytoplasmic areas (4), while also areas with no substantial co-localization could be observed (5). B, (left) Histograms collected from 74 HT-22 cells, reflecting a percentage of co-localized immunoreactivities relative to the total amount for each of two receptors, observed in separate cells. (right) Cumulative histograms of co-localization coefficients (CC) yielded medians at 0.105 for ERβ and 0.347 for RyR2. The control, low intensity non-specific secondary antibody binding, which was cutoff at 25% through a high-pass numerical filtering during CC calculations (see Methods), is illustrated in panel A,1.

An interaction between ERβ and RyR could be hypothesized based on reports on direct effects of E2 on ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+i stores [26, 36] and our data above. Presently, little is known about mechanisms of ER protein-protein interactions outside genomic activities in transcriptional regulations. Both unliganded and liganded forms of ERs are capable of interacting with a series of binding proteins through various binding domains [2]. For ERβ, unlike ERα, a stable monomer is formed in the unliganded (or “antagonist”) molecular conformation, in which ERβ might interact with various proteins [1, 9, 44]. In the present study, we focused on the unliganded (i.e. E2-free) full-length isoform ERβ1, which contains all active molecular domains needed to perform functional tests for RyR/ERβ interaction, and present in other shorter ERβ isoforms, some of which lack ligand-binding domain (LBD) or possess a low-affinity LBD [43]. Commercially available recombinant ERβ1, filtered and diluted in Hepes/Tris buffer (see Methods and Fig. 3) was used for experiments. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments between RyR2 from mouse brain lysates and recombinant ERβ in Ca2+-free conditions and at pCa6 (1 μM) did not reveal a significant interaction (data not shown) indicating an absence of stable complexes, but leaving a possibility for transient interaction between the two proteins. This finding would be in line with variable ERβ/RyR2 co-localization patterns probably reflecting certain intracellular ERβ diffusion restrictions, as described above.

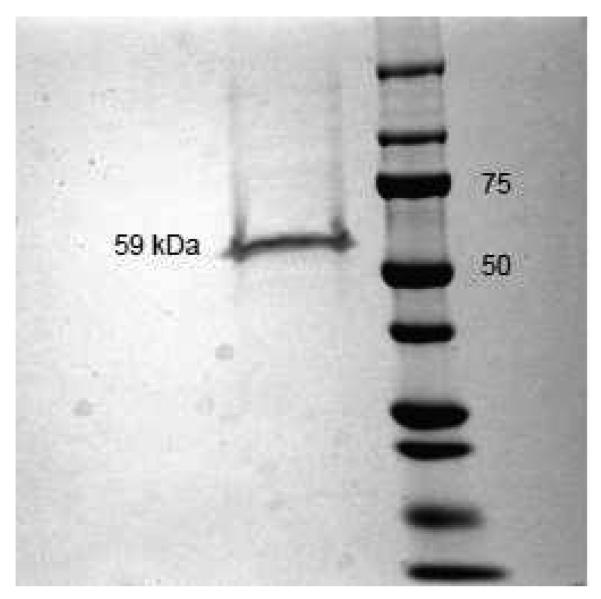

FIGURE 3. Chromatographic recombinant ERβ used in the electrophysiological experiments.

Coomassie blue staining of recombinant ERβ (Invitrogen) after SDS-PAGE reveals a single band at ~59 kDa, which corresponds to the full-length isoform ERβ1. In the right lane, bands of molecular weight standards are presented and their respective molecular weight is indicated in kDa.

To explore the possibility of functional regulation of RyRs by ERβ via diffusional interaction, we performed electrophysiological experiments using RyRs from mouse brain cortex microsomes incorporated in artificial lipid bilayers. As we have previously described, brain microsomal RyRs generate single channel currents of two modes: fluctuating and stable sublevels (with fully opened single channel level at ~ −4pA in our experimental conditions), which can be observed eventually at the same channel [48], with molecular determinants underlying both modes yet to be identified. Addition of unliganded ERβ1 monomer to the cytoplasmic side of the RyR at concentrations as low as 5 nM shifted RyR single channel openings towards higher sublevels. This effect is illustrated in current traces, sublevel histograms and ratios of sublevel probabilities obtained after ERβ1 treatment relative to control values for representative RyR generating “fluctuating” single channel current in Fig. 4. RyR activation by ERβ1 was, however, phenomenologically different from simple-kinetics instantaneous effects observed for other proteins in our previous studies [48, 49]. The increase in single channel open probability to higher sublevels occurred within a minute after ERβ1 application, but the peak of channel activity was usually observed after a several minutes of exposure, followed by a relatively short transient decrease in RyR channel activity in the continuous presence of ERβ1. This transient decrease was finally reversed by subsequent stabilization of the RyR channel activity at various levels around the initial peak activity. This biphasic activating effect of ERβ1 on RyR was observed in 16 out of 20 channels analyzed. A representative experiment using 10 nM of ERβ1 is shown in Fig. 5. Typical RyR single channel current traces and a typical mean current (Imean) time-course are shown in Fig. 5A and 5B, respectively. Statistical analysis of the Imean parameter collected from nine RyR channels, sampled during control 60 s recordings before (tcontr 1 = −7±2 min, tcontr2 = −3±1 min, s.d.) and several repeated recordings after application of 10 nM ERβ1 (tappl = 0), shows an initial peak in channel activity (~ 1.9 times, tpeak = 6±4 min, s.d.), subsequent partial inactivation (tinact = 10±5 min, s.d.) and recurred stabilization (tstab = 16±7 min, s.d.) of the RyR channel activity resulting from its interaction with ERβ1 (Fig. 5C). The molecular nature of this biphasic activation of the RyR by ERβ1 could reflect a co-operative effect of multiple ERβ1 molecules or binding of a single ERβ1 molecule with RyR sequentially at multiple sites through induced-fit of ERβ1 flexible domains [2]. A major separate conclusion is that apart from the intracellular co-localization of RyRs and ERβ, both proteins are capable of direct protein-protein interactions through cytoplasm-exposed domains that change the functional state and biophysical properties of RyR ion channels.

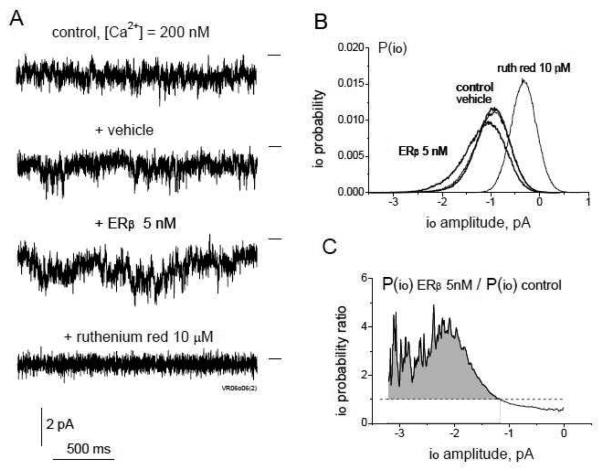

FIGURE 4. ERβ applied at low nanomolar concentrations increases the open probability of higher subconductance states of the RyR channel.

A, Representative 2 s long traces of a continuous single channel current recording from the same RyR obtained at [Ca2+]cis = 200 nM, after addition of vehicle solution, ERβ (5 nM) and the RyR blocker ruthenium red (10 μM). The closed state is indicated by a horizontal line to the right of each trace. B, Open probability histograms for channel current sublevels io (P(io)) calculated from 60 s of continuous current recording at the same experimental conditions as in A, show no effect of the vehicle solution but increased RyR channel open probability to higher io sublevels after ERβ application. C, Ratio of P(io) values calculated before and after 5 nM ERβ application, indicating a 2-4 fold increase in P(io) after ERβ application over the entire range of RyR open sublevels.

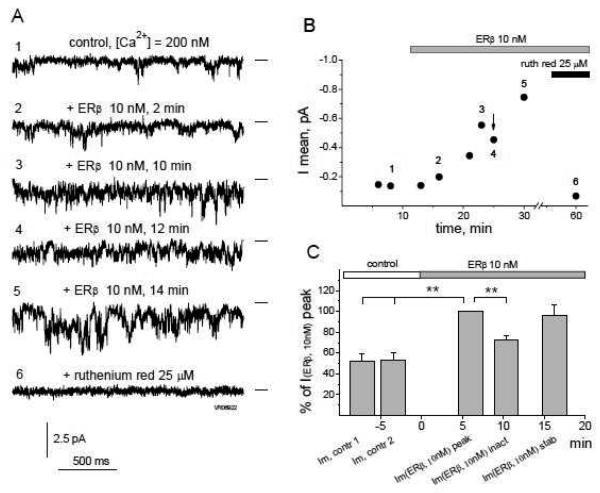

FIGURE 5. The effect of ERβ on RyR single channel current characteristics is biphasic over time.

A, Representative 2 s long traces of a continuous single channel current recording from the same RyR obtained in chronological order at [Ca2+]cis = 200 nM (1) and 2 min (2), 10 min (3), 12 min (4) and 14 min (5) after ERβ (10 nM) application, followed by subsequent complete channel block with 25 μM of ruthenium red (6). B, Time-course of the mean current (Imean) calculated from 60 s continuous recordings of the experiment presented in part A. Notable is a typical transient decrease in the Imean after the initial channel activation by ERβ (arrow), followed by stabilization of the activation effect. Numbers on the graph correspond to the time intervals for representative traces in part A. C, Averaged Imean values obtained from 9 different RyRs during two control 60 s intervals preceding the application of ERβ 10 nM (Imean,contr 1 & Imean,contr 2), and during intervals of the initial increase (Imean, peak), transient inactivation (Imean, inact) and stabilization (Imean, stab) of the RyR single channel current activated by 10 nM ERβ (see text). Data are normalized by the Imean(ERβ, 10nM)peak point corresponding to the initial RyR activation by ERβ. (**, p<0.01).

The effect of increased RyR channel activity was more pronounced at higher ERβ1 concentration. Fig. 6 shows the stimulating effect of ERβ1 on RyR with an initially low basal activity at a cytosolic pCa 6 (1 μM), after application of 20 nM ERβ1. Stable openings to a half-open state (2pA, S2) and to higher sublevels (including the fully open 4pA, S4 state) are measured at the peak of channel activation 7 min after ERβ1 application (Fig. 6A, 2-3) with a distinct peak in the current histogram (Fig. 6B). A typical transient reduction of channel activity occurs 10 min after ERβ1 application (Fig. 6A, 4-5; B, histogram peak shifted to the right). Ruthenium red completely blocks the channel (Fig. 6A, 6). Statistical analysis of the Imean values at the peak of channel activation by 20 nM ERβ1 collected from 10 RyR channels (Fig. 6C) showed a significant increase in channel activity by 20 nM ERβ1 relative to controls (~ 2.1 fold).

FIGURE 6. Higher ERβ concentrations stimulate longer open dwell-times and open sub-states of RyR channel.

A, Representative 2 s long traces of a continuous single channel current recording from the same low activity RyR obtained at [Ca2+]cis = 1 μM (1) and after ERβ (20 nM) application for 7 min (2,3) and 10 min (4,5), followed by the ruthenium red (25 μM) block (6). Closed state (C) and io=2pA (S2) and io=4pA (S4) sublevels are marked to the right of traces. B, P(io) histograms calculated from 2 min continuous current recording traces reveal an additional peak reflecting stable RyR openings at around the S2 sublevel after 20 nM ERβ treatment. C, Averaged mean current (Imean) obtained from 60 s long RyR single channel recordings at control conditions ([Ca2+]cis = 200 nM or 1 μM) and after application of the vehicle or ERβ (20 nM) containing solutions. The number of data points from different experiments taken for averaging is presented at the bottom of the columns. (*, p<0.05).

To analyze the mechanism underlying the RyR/ERβ interaction, we measured three different biophysical parameters of RyR single channel currents. Imean is a parameter reflecting the contribution of the channel low-amplitude current noise characterizing a general ability of the RyR to “leak” Ca2+ from the lumen of the E.ret into the cytoplasm, and thereby is a robust measure of the influence of the RyR on basal Ca2+i levels. Parameters reflecting RyR channel open probability (Po) to higher sublevels (i.e. S2 and fully open S4 substates) better characterize the ability of RyR to release Ca2+i in response to stimulation of intracellular Ca2+ signaling cascades. We calculated changes in Imean, Po(S2) and Po(S4) under control conditions and at the peak of activation by ERβ1 (Fig. 7). Both 10 and 20 nM of ERβ1 markedly increased all three measured RyR single channel parameters. Application of 10 nM ERβ1 resulted in an increase of Imean by 1.8, Po(S2) by 2.2 and Po(S4) by 25-fold. Application of 20 nM ERβ1 resulted in a higher increase of measures of RyR activity: Imean 3.3, Po(S2) 20 and Po(S4) 152-fold. The most pronounced change was seen for the Po(S4) parameter at 20 nM ERβ1, but did not reach a significance difference (p<0.05) due to the variability of the activating effect (ranging from 1.3 to 416-fold increases) and a limited number of channels generating a fully open state S4, which is typical for the analysis of this parameter, according to previous studies [48]. The data in Fig.7 provide evidence for an increase in RyR open probability at higher sublevels as a result of the interaction with ERβ1. To verify this hypothesis, we performed a series of experiments examining the effect of ERβ1 application at various cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations ranging from pCa7 (100 nM) at which RyR single channel currents are represented mostly by low-amplitude noise fluctuations, to pCa4 (100 μM) when RyR channels reach maximal activity, including openings to higher sublevels and fully open states. The statistical analysis of the Ca2+-dependence of ERβ1 effects on RyR single channel parameters is shown in Fig. 8. The data obtained with 10 and 20 nM ERβ1 were pooled together due to the similarity of effects observed at all tested cytosol Ca2+ concentrations. Averaged Imean values (Fig. 8 top) were increased significantly after ERβ1 application by factors of ~1.4, ~2.4, ~2.5 and ~3.4 at pCa7 (100 nM), pCa6 (1 μM), pCa5 (10 μM) and pCa4 (100 μM), respectively. Higher increase was observed at higher cytosol Ca2+ concentrations, at which RyR channels usually open to higher sublevels and contribute accordingly to Imean. For Po(S2) (Fig. 8 middle), a moderate increase by ERβ1 at pCa7 (~1.7-fold) contrasted with strong increase at pCa6 (~17-fold) when open sublevels around S2 are often dominant, was seen. A reduction to ~11-fold and ~6.4-fold increase in Po(S2) at pCa5 and pCa4 respectively, as a consequence of openings to the S4 rather than the S2 state, was measured at higher cytosol Ca2+ concentrations. The strongest effect of ERβ1 exposure was observed on the Po of the fully open channel (S4 subconductance state, Fig.8 bottom). Full channel openings to the S4 level, which are almost absent at pCa7, were increased ~19-fold after addition of ERβ1. For pCa 6, 5 and 4, ERβ1-induced increases in Po(S4) were ~280, ~680 and ~2300 respectively. (Fig.8). The major effect of the interaction between unliganded ERβ1 and brain RyRs is an increase in the open probability of higher RyR subconductance states, particularly at higher Ca2+i concentrations that are typical for transient Ca2+i elevations seen during signaling events.

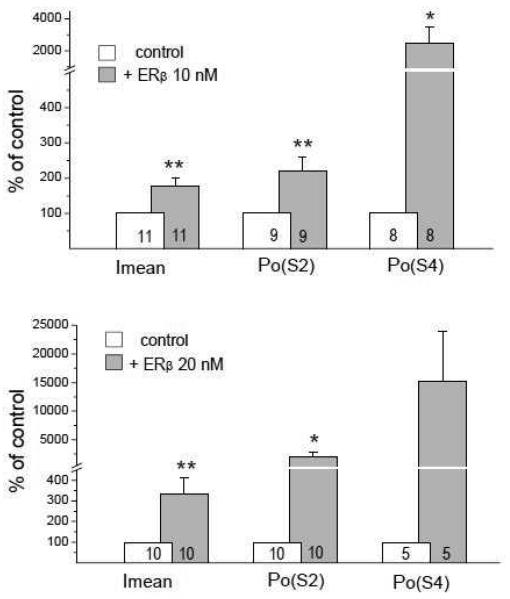

FIGURE 7. ERβ dose-dependently increases the open probability of higher RyR subconductance states.

Mean current (Imean) and open probabilities for −2 pA (Po(S2)) and −4 pA (Po(S4)) sublevels calculated for individual RyRs during the initial peak increase of the RyR channel activity by the ERβ applied at concentrations of 10 nM (top panel) and 20 nM (bottom panel). The number of averaged points is presented on the bottom of the columns. (**, p<0.01; *, p<0.05).

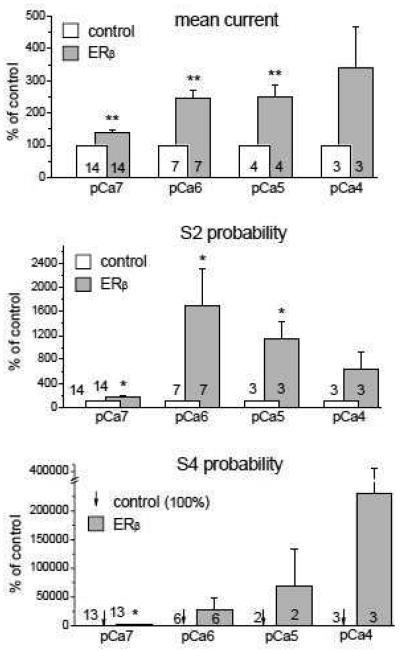

FIGURE 8. ERβ and Ca2+ increase RyR single channel activity synergistically.

The columns represent averaged values of Imean (top), Po(S2) (middle) and Po(S4) (bottom) normalized to the control conditions before ERβ application that had been calculated for individual RyRs during the initial peak increase of the RyR channel activity induced by the ERβ application (10 or 20 nM) as a function of [Ca2+]cis concentrations (pCa 7, 6, 5 and 4). Arrows at the bottom panel (S4 probability) indicate the control values (100% level), which cannot be distinguished due to their small size. The activating effect of ERβ on the fully open S4 state of the RyR is more pronounced at higher [Ca2+]cis (i.e. pCa 4). (**, p<0.01; *, p<0.05).

To test whether RyR modulation by ERβ1 might contribute to toxicity caused by elevated intracellular Ca2+, maintenance of RyR inactivation at high cytosolic Ca2+ in the presence of ERβ was analyzed. Fig.9 shows a representative experiment when cytosolic Ca2+ was increased to pCa 3 (1 mM) during activation of the low-activity RyR channel by 10 nM ERβ1. Application of 10 nM ERβ1 markedly increased channel activity at pCa 5 (Fig. 9A,3) which was further increased at higher cytosolic Ca2+ (pCa4, Fig. 9A,4). Subsequent further increase of cytosolic Ca2+ to pCa 3, however, showed the typical channel inactivation of RyR in the presence of ERβ1 on the cytoplasmic side of the channel (Fig. 9A,5). Inhibition of the RyR by high Ca2+ concentration overrides the activating effect of ERβ1, which supports the conclusion that ERβ is a physiologically relevant controlled modulator of RyR activity. The time-course of the experiment (Fig. 9B) illustrates all major observations: biphasic activation of the RyR by ERβ1 (points 2-3), a synergistic activating effect of ERβ1 at high cytosolic Ca2+ concentration (point 4) and RyR inactivation by very high Ca2+ concentration (point 5). The current histograms (Fig. 9C) together with the representative single channel current traces (Fig. 9A) illustrate RyR channel activity manifested as short-living open conformational states and stable full-open states (Fig. 9A,4 & C,4).

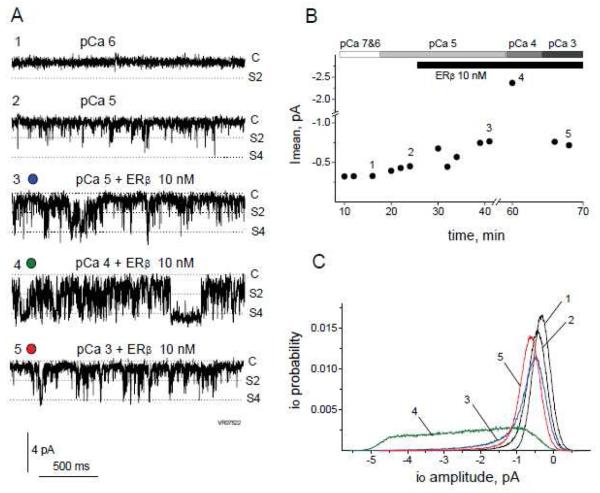

FIGURE 9. Maintenance of RyR Ca2+ dependence in the presence of ERβ.

A, Representative 2 s long traces of a continuous single channel current recording from the same RyR obtained at pCa 6 (1), pCa 5 before (2) and after (3) 10 nM ERβ application and at pCa 4 (4) and pCa 3 (5) in the presence of 10 nM ERβ. Closed state (C), io=2pA (S2) and io=4pA (S4) substates are marked to the right of each trace. B, Time-course presentation of the mean current (Imean) values calculated from 60 s continuous recordings. Bars on top indicate the time course of [Ca2+]cis changes and ERβ application. Notable is a sharp decrease in Imean values at pCa 3 due to the RyR inactivation after a strong previous increase in Imean at pCa 4 in the presence of 10 nM ERβ. Numbers on the graph correspond to the time intervals for representative traces in part A. C, P(io) histograms calculated from 60 s continuous current recording traces (corresponding to numbered intervals from part B). A broad range of io sublevels appearing at pCa4 (line 4) decreases at pCa3 (line 5) due to the RyR inactivation.

DISCUSSION

The involvement of ERβ in the non-genomic regulation of intracellular signaling cascades is potentially driven by molecular mechanisms of ERβ interaction with non-nuclear proteins. E2-activated ERβ might interact with PM signaling molecules, which produce second messengers (including Ca2+ entry) and/or activate kinases, which initiate intracellular signaling cascades. While the experiments performed with E2 conjugated to PM-impermeable carriers do not provide unambiguous conclusions regarding functional PM ERs [4, 25, 26], the E2-induced activation of PM proteins such as mGluR, PLC and L-type Ca2+ channels in hippocampal neurons [23], guanylate cyclase in LHRH-producing cells [50] supports the ER-mediated initiation of cellular signaling from the PM. This notion was corroborated by the detection of moderate amounts of ERβ in PM [29]. The role of cytoplasmic ERβ (e.g., H-150 antibody-reactive), which is not subject to nuclear translocation upon E2 treatment [30, 47] needs further mechanistic analysis. ERβ is potentially involved in rapid E2-evoked Ca2+i transients, which, through Ca2+-dependent eNOS activation [37] can lead to NO production in the absence of extracellular Ca2+ [33]. Cytoplasmic ER signaling via eNOS potentially does not require ER dimerization [25], but the identification of cytoplasmic ER location and of cytoplasmic effector proteins is still lacking. A potential cytoplasmic function of ERβ leading to intracellular Ca2+ mobilization can be inferred from experiments measuring Ca2+i-dependent ERK activation in hippocampal neurons: faster kinetics of ERK activation was seen with the ERα agonist PPT and slower kinetics with the ERβ agonist DPN [20] potentially due to fast Ca2+i fluxes mediated by PM ERα and delayed Ca2+i release mediated by cytoplasmic ERβ. This potential mechanism parallels data from GnRH neurons of ERβ KO mice indicating an involvement of cytoplasmic ERβ in E2-mediated, generally Ca2+i-dependent [23] CREB phosphorylation, which could not be reproduced with PM-impermeable BSA-E2 applied at moderate concentrations [51]. Thus, based on a series of indirect observations, intracellular non-nuclear ERβ might interact directly with intracellular proteins controlling intracellular Ca2+ release and thereby activate Ca2+i-dependent proteins and kinases. Consequently, ERβ can potentially regulate eNOS, relevant for E2/ERβ-mediated cardio-vascular protection against ischemia-reperfusion injury [10, 11], central regulation of blood pressure [52] and potentially beneficial effects on functional parameters after heart trauma-hemorrhage injury, which were also mediated by ERβ [40].

E.ret membrane resident IP3Rs and RyRs are likely cytoplasmic targets for ERβ-mediated Ca2+i release. IP3Rs are potential downstream effectors of PLC activated by PM-associated ERs [23]. RyRs are potentially involved in intracellular Ca2+ release via E2/ER-activated protein-kinases or direct ER/RyR interaction. E2-activated ERs can modulate protein kinase pathways [3, 53], which potentially can target one of the canonical regulatory sites (e.g. for PKA), present at the cytoplasmic mouth of the RyR [41, 42]. However, a direct link between E2-stimulated protein kinases and modulation of RyR function has not been reported yet. Alternatively, activation of various kinases [13, 19, 23, 54] are possible downstream processes following Ca2+i transients produced by RyRs stimulated by E2/ER signaling. In a cellular system, it is difficult to distinguish whether RyRs are upstream or downstream of E2/ER-dependent kinase. Previously published data in various cell types, where prolonged Ca2+i transients after application of E2 (or alternative ER ligands) were recorded in extracellular Ca2+-free conditions and where a contribution of the PLC/IP3R cascade was ruled-out [13, 34-36], could not distinguish whether or if the ERs acted on RyR directly or indirectly. The present study represents the first attempt to detect whether ERβ can directly influence RyR activity, envisioning a hypothesis that RyRs are ERβ-modulated upstream element of Ca2+i-dependent proteins and their signaling. ERβ/RyR2 co-localization in HT-22 cells (Figs. 1 and 2) presents evidence that ERβ and RyR2 can be found coexpressed in the cell allowing for potential molecular interaction. The electrophysiological experiments (Figs. 3-9) provide direct evidence that freely diffusing ERβ1 monomers interact with cytoplasmic domain(s) of the RyR and modulate its gating properties.

Based on the present experimental data and on published molecular properties of both proteins, conclusions regarding mechanisms underlying the ERβ1/RyR interaction can be drawn. The biphasic time-course of RyR channel activation by ERβ1 (Fig. 5) indicates that modulation of channel activity may involve serial binding of multiple ERβ1 molecules to different RyR subunits, with RyR channel activity reduced in one of the intermediate occupancy conformation states relative to lower and higher occupancy conformation states. The RyR binding sites accommodating ERβ1 molecules during serial binding might be of different affinities due to allosteric conformational changes of the RyR after each successive ERβ1 binding step. The structure of the ER molecule, which possesses at least three protein-binding domains (AF-1, AF-2 and hinge domain) and a certain level of flexibility [2] allows an induced-fit of AF-1 to a binding partner after the initial binding of ER through either the AF-2 or hinge domains. Such an induced-fit occurring during interaction with RyR through multiple dynamically induced ERβ1 binding sites could generate a series of RyR conformations resulting in biphasic channel activation as observed in our experiments using the full-length ERβ1 isoform.

There is both molecular basis and physiological evidence for non-genomic effects of ERs in the absence of estrogens. Unliganded ERs are capable in certain conformational [9] or functional states [1, 6] to interact with other proteins, such as Hsp90 and Hsp70 [55], human L7/SPA corepressor [56] and CaM-binding protein striatin [57]. More specifically, unliganded ERβ but not ERα is capable to interact with SRC-1, inducing E2-independent transcriptional activity [1], and with human MAD2 protein controlling arrest of mitosis [44]. The higher ability of ERβ than ERα for protein-protein interaction in the unliganded state might originate from differences in the primary sequence and structures of the AF-1, hinge and ligand-binding AF-2 domains between two ERs [1, 2, 9, 58]. The ability to interact with proteins in the absence of estrogens may reflect a general function of ERs in intracellular signaling, providing functional independence from changing estrogens levels or their cyclical or age-dependent variations. Multiple studies indicate the existence of physiological processes involving unliganded ERs. ERβ is expressed in the cortex of the mouse embryonic brain on day E15 and functions without estrogens until E18, when the first synthesis of E2 occurs [59]. The mechanism by which ERβ controls the prepubertal uterus before the ovaries begin generating E2 remains to be determined [9]. At the cellular level, expression of ERα and subsequent treatment with E2 inhibited proliferation of the breast cancer line MDA-MB-231. The same level of inhibition was achieved by expression of ERβ alone (without E2 treatment) [7]. Similarly, ERα downregulated the expression of Ca2+-activated apoptotic protease m-calpain ligand-independently in SK-N-MC neuroblastoma cells, while co-expression of ERβ counteracted the effect [60].

The present study provides evidence for a role for unliganded ERβ in Ca2+i homeostasis by interacting with and modulating functions of RyRs. The unliganded and E2-bound ERβ forms have the potential to differentially interact with RyRs, providing various modalities of RyR regulation, analogous to the interaction of unliganded ERα and striatin, which could be enhanced by E2 [57]. Also remains to be determined if RyRs interact with shorter ERβ isoforms that lack or have a transformed ligand-binding domain, resulting in the reduced or absent ability to bind E2, i.e. ERβ2,3,4,5 [43]. RyR modulation by these short “orphan” isoforms of ERβ receptors might be part of their so far elusive physiological role. Our electrophysiological data indicates that in the absence of estrogens, interaction of ERβ with RyR leads to moderate leakage of Ca2+ from the E.ret providing a basal level of RyR channel activity, as well as sensitization of RyRs to E2-activated signaling originating from PM-associated ERs upon stimulation of the cell with E2. An example of similar RyR sensitization was described in recent work using the sweat gland cell line NCL-SG3, where E2 alone could not evoke Ca2+i release from ryanodine-sensitive stores in extracellular Ca2+-free conditions, unless E2 was applied together with Ca2+-release agent Tg, which also produced only a small Ca2+ transient when applied alone [36], suggesting that elevated basal Ca2+i was necessary to reduce the threshold for triggering E2-dependent Ca2+i release from ryanodine-sensitive stores. The presence of ERs in both the PM and E.ret compartments might serve the coupling of E2-stimulated signaling originating from the PM, such as ERα-initiated activation of IP3 cascade leading to primary Ca2+i release [23, 28], with CICR from E.ret mediated by ERβ-sensitized RyRs. A primary intracellular Ca2+ transient generated by either IP3Rs or PM VOCC might be necessary to initiate CICR, since ERβ and Ca2+ act synergistically to stimulate RyR full opening (Fig. 8). Thus, acting on E.ret RyRs, the cytoplasmic ERβ (either unliganded or liganded) could be used by the cell in multiple ways to tune Ca2+i release and downstream Ca2+-dependent mechanisms, providing even more variety for integration between membrane, cytoplasmic and nuclear effects of estrogens [25, 26].

The complexity of ER signaling in various cell types might explain in part the failure of clinical trials testing the beneficial effects of hormone therapy, despite high potential of estrogens for neuroprotection [53]. Critical might be poorly understood role of ERs in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis, since E2 administration typically enhances viability of neurons with intact Ca2+i metabolism, but exacerbates Ca2+i toxicity in neurons with Ca2+ dyshomeostasis [61]. One component of neuronal viability is the ability to grow and maintain dendrites and form synaptic connections. In hypothalamic VMN and hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons devoid of nuclear ERs, growth of dendrites undergoes cyclical peaks following changes in E2 concentrations during estrous cycle [62], suggesting an important role for non-genomic effects of ER signaling in this process. The involvement of ERβ is plausible, since it has been shown that in the developing embryo the ERβ mRNA is detectable from E10.5 before E2 production and the appearance of ERα mRNA at E16.5, and that cortical neuronal migration, differentiation and survival in developing brain is markedly impaired in ERβ KO mice [59, 63]. At the same time, RyR-mediated Ca2+i release following activation of the IP3 cascade plays a critical role in neuronal migration and chemical cue detection. Asymmetric distribution of Ca2+i concentrations in the soma and significant elevation of Ca2+i in growth cones are key determinants for directed neuronal migration [64]. Remarkably, we found high levels of RyR/ERβ co-localization in corresponding compartments in HT-22 cells in our immunocytochemical study (Fig.1,1; Fig. 2A,3), which could indicate that the measured positive modulation of RyRs by unliganded ERβ1 might play a role in neuronal migration and differentiation. In addition, this notion is further supported by recent work describing active Ca2+i release by RyRs upon stimulation of IP3 cascade with netrin-1 in areas of future axonal branching, shortly before protrusion of a new branch [65]. In the present study, we saw high RyR/ERβ co-localization in areas of neurite branching in HT-22 cells (Fig.1,2), indicating the possible physiological significance of the RyR/ERβ interaction during neuronal differentiation and neurogenesis.

In sum, the present study indicates that in the absence of estrogens, ERβ can dynamically associate with RyR creating conditions for RyR/ERβ interaction, which results in significant activation of RyRs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Immunocytochemistry

Materials

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's medium with 4.5 g/mol glucose, 2mMglutamine, 1mM sodium pyruvate (Hyclone, Logan, UT) containing 10% heat-inactivated bovine growth serum (BGS, Hyclone) (DME+); paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Fisher, Fair Lawn, NJ); 0.1M PBS pH 7.4 (Fisher, Fair Lawn, NJ); Triton-X 100 (MPBiomedicals, Aurora, OH); Aqua-Polymount (Polysciences, Inc.,Warrington, PA). Mouse antibody raised against RyR2, (clone C3-33; MA3-916, Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO); rabbit polyclonal antibody against estrogen receptor beta (ERβ)(H-150) (sc-8974, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); secondary goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit IgG antibodies coupled to Alexa Fluor® 488 or Alexa Fluor® 594, respectively (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, CA), Hoechst counterstain (B2261, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Double immunostaining

HT22 cells were grown on coverslips as previously described [66]. Media (DME+) was removed and attached cells were fixed for 20 min in 4% PFA (0.01 M PBS, pH 7.4) at room temperature (RT). Fixative was removed, followed by two 10 min washes using PBS (0.01 M PBS, pH 7.4). Blocking solution (10% normal goat serum, 1% BSA and 0.05% Triton-X 100 in 0.01 M PBS) was added and cells were incubated for 1 hour. After blocking, the cells were incubated overnight with the primary antibodies (each diluted 1:50 with 3% normal goat serum, 1% BSA and 0.05% Triton-X 100 in 0.01 M PBS in a humidified chamber, protected from light at 4°C. After 3 washes with PBS, cells were incubated with both secondary antibodies (1:1000 dilution each) and nuclear counterstain (0.5 ng/ml) for 1 hour at RT, in a humidified chamber and protected from light. After 3 washes, coverslips were mounted on slides using Aqua-Polymount. Negative controls consisted of the omission of primary antibody.

RyR/ERβ co-localization study

Confocal microscopy

Images were acquired with a Zeiss confocal laser-scanning microscope (LSM510; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) with a 40x water-immersion objective. Alexa 488 was imaged with an Argon/2 laser and a band pass emission filter (505-550nm). Alexa 594 was imaged using a 561nm laser with a 575nm long pass emission filter. Horizontal optical sections from a region of interest around the analyzed cell (z-stack with 0.45 μm z-step, 1.0 optical slice thickness) were saved as 12 bit TIF files (1024×1024 pixel images). All images were acquired with the same confocal settings to ensure uniformity of labeling for each cell, including pinhole size, detector gain, offset, and laser power. To remove the possibility of non-specific secondary antibody binding contributing to the level of colocalization, control coverslips with omitted primary antibodies were used to adjust gain and offset on the confocal microscope, to leave the level of intensity of background pixels for each of the fluorophores (AlexaFluor 488 and AlexaFluor 594) below the intensity level of 1029 (i.e. 25% of maximal intensity). Once these settings were determined, all subsequent images were acquired with the identical settings.

Co-localization data analysis

Colocalization between RyR2 and ERβ immunoreactivities was analyzed using a standard algorithm, available as a built-in module in the Zeiss LSM 5 Duo software. An intensity threshold above 1029 (i.e. 25% of maximal intensity) for each channel (apparent as green for RyR2 and red for ERβ in Figs. 1 and 2) was taken into analysis as representing a true staining. The number of co-localized pixels was counted in each optical section separately and results from all sections were added for an individual cell. For each cell, the co-localization coefficients (CC) were calculated separately for the green (CCRyR) and red (CCERβ) channels using the ratio formulas of CCRyR=Ngreen,coloc/Ngreen,total and CCERβ=Nred,coloc/Nred,total (where Ncoloc and Ntotal are numbers of co-localized vs. total pixels for a particular color channel having above-threshold intensities), which represent the relative amount of immunoreactivities for RyR2 colocalized with ERβ and ERβ co-localized with RyR2, respectively. To verify whether the co-localization pattern is not due to a random chance, we rotated the data in the red channel 90 degrees and measured the co-localization coefficients using the algorithm described above. No significant co-localization occurred in superimposed normal and rotated images.

ERβ coomassie blue staining

Purified and filtered recombinant ERβ (cat # P2718, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was subjected to native, non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subsequent Coomassie blue staining revealed a single band of approximately 59 kDa, which corresponds to the full-length isoform of the ERβ1 monomer.

RyR single channel electrophysiology

Microsome preparation and RyR single channel recordings were done as described earlier [48, 49, 67, 68]. The cortex tissue from brains of adult Swiss Webster mice was homogenized and diluted in a buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 5 mM Hepes, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and Complete® protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) tablet (pH 7.4 adjusted with KOH), then centrifuged at 1,000 g at 4°C. The supernatant was pooled and centrifuged at 8,000 g in the same buffer. The pellet was discarded and the supernatant was re-centrifuged at 100,000 g. The microsome-containing pellet was collected, diluted in the buffer of the same composition, but without EGTA, aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

RyR-containing microsomes added to the cis compartment of the bilayer chamber (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT), were fused to a lipid bilayer (formed on a Ø150-200 μm aperture with 3:1 mixture of dried phosphatidylethanolamine/phosphatidylserine lipids (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) dissolved in decane), using hyperosmotic KCl conditions. After RyR incorporation, the “cytoplasmic” cis chamber buffer contained 93 mM TrisOH / 190 mM HEPES, pH=7.35, ~285 mOsm and “lumen” trans chamber contained 50 mM Ba(OH)2 / 245 mM HEPES, pH=7.35, ~ 285 mOsm. RyR-mediated single channel currents were activated by buffering [Ca2+] in the cis chamber with rationed amounts of CaCl2/EGTA calculated using MaxChelator software (Stanford University, http://www.stanford.edu/~cpatton/maxc.html) and verified by Ca2+-selective electrode (KWIK-2, WPI). Recombinant human estrogen receptor beta, conventional long isoform (ERβ1) (cat # P2718, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was filtered (Slide-A-Lyser Mini Dialysis Units, cat # 69550, Pierce, Rockford, IL) using cis buffer for elution and concentration of the protein was measured using Bradford assay. ERβ1 was diluted to 2 μM concentration, aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. The molecular weight of the ERβ1 dissolved in the cis buffer was measured using a conventional Coomassie blue staining (Fig.3). ERβ1 was added to the cis chamber where the cytoplasmic side of the RyR resides after microsome incorporation, to examine its effect on RyR single channel current characteristics. The RyR blocker ruthenium red (10 to 25 μM) was routinely added at the end of the experiment to verify the identity of the RyRs. Electrophysiological measurements were performed at RT.

RyR single channel currents were recorded at a holding potential of 0 mV (trans chamber grounded) using BC-525 amplifier (Warner Instruments), filtered at 500 Hz and digitized at 5kHz using Digidata 1322A acquisition system and pClamp 9 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Off-line current trace filtering, and calculations of mean single channel current (Imean) and open channel probabilities for S2 (−2pA) and S4 (−4pA) RyR sublevels ((Po(S2) and Po(S4)) were done using pClamp 9. The histograms of currents corresponding to various open levels of the RyR channel (io) were calculated from 60 s long continuous segments of current recordings. OriginPro 7.5 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA) was used for statistical analysis and data presentation. The p-values for estimation of significant differences between population means were calculated using one-way ANOVA test using OriginPro 7.5 built-in statistical analysis functionality. Unless otherwise stated (i.e. for time intervals tcontr , tappl and tpeak explained and presented in Fig.5,C using ± s.d.), data in Result section and in figures are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported in part by grants EY014227 from NIH / NEI, RR022570 from NIH/NCRR and AG010485, AG022550 and AG027956 from NIH / NIA as well as by The Garvey Texas Foundation (P.K.). We thank Margaret, Richard and Sara Koulen for generous support and encouragement.

References

- 1.Pettersson K, Gustafsson JA. Role of estrogen receptor beta in estrogen action. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2001;63:165–192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ascenzi P, Bocedi A, Marino M. Structure-function relationship of estrogen receptor alpha and beta: impact on human health. Mol. Aspects Med. 2006;27:299–402. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maggi A, Ciana P, Belcredito S, Vegeto E. Estrogens in the nervous system: mechanisms and nonreproductive functions. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2004;66:291–313. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032802.154945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raz L, Khan MM, Mahesh VB, Vadlamudi RK, Brann DW. Rapid estrogen signaling in the brain. Neurosignals. 2008;16:140–153. doi: 10.1159/000111559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krege JH, Hodgin JB, Couse JF, et al. Generation and reproductive phenotypes of mice lacking estrogen receptor beta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1998;95:15677–15682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hall JM, Couse JF, Korach KS. The multifaceted mechanisms of estradiol and estrogen receptor signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:36869–36872. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lazennec G, Bresson D, Lucas A, Chauveau C, Vignon F. ER beta inhibits proliferation and invasion of breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2001;142:4120–4130. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.9.8395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watanabe T, Akishita M, Nakaoka T, et al. Estrogen receptor beta mediates the inhibitory effect of estradiol on vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2003;59:734–744. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(03)00496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koehler KF, Helguero LA, Haldosen LA, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Reflections on the discovery and significance of estrogen receptor beta. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:465–478. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabel SA, Walker VR, London RE, Steenbergen C, Korach KS, Murphy E. Estrogen receptor beta mediates gender differences in ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy E, Steenbergen C. Gender-based differences in mechanisms of protection in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc. Res. 2007;75:478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beyer C, Raab H. Nongenomic effects of oestrogen: embryonic mouse midbrain neurones respond with a rapid release of calcium from intracellular stores. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998;10:255–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Improta-Brears T, Whorton AR, Codazzi F, York JD, Meyer T, McDonnell DP. Estrogen-induced activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase requires mobilization of intracellular calcium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1999;96:4686–4691. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Picotto G, Vazquez G, Boland R. 17beta-oestradiol increases intracellular Ca2+ concentration in rat enterocytes. Potential role of phospholipase C-dependent store-operated Ca2+ influx. Biochem. J. 1999;339(Pt 1):71–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doolan CM, Harvey BJ. A Galphas protein-coupled membrane receptor, distinct from the classical oestrogen receptor, transduces rapid effects of oestradiol on [Ca2+]i in female rat distal colon. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2003;199:87–103. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaban VV, Lakhter AJ, Micevych P. A membrane estrogen receptor mediates intracellular calcium release in astrocytes. Endocrinology. 2004;145:3788–3795. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koldzic-Zivanovic N, Seitz PK, Watson CS, Cunningham KA, Thomas ML. Intracellular signaling involved in estrogen regulation of serotonin reuptake. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2004;226:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bulayeva NN, Wozniak AL, Lash LL, Watson CS. Mechanisms of membrane estrogen receptor-alpha-mediated rapid stimulation of Ca2+ levels and prolactin release in a pituitary cell line. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2005;288:E388–397. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00349.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu TW, Wang JM, Chen S, Brinton RD. 17Beta-estradiol induced Ca2+ influx via L-type calcium channels activates the Src/ERK/cyclic-AMP response element binding protein signal pathway and BCL-2 expression in rat hippocampal neurons: a potential initiation mechanism for estrogen-induced neuroprotection. Neuroscience. 2005;135:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao L, Brinton RD. Estrogen receptor alpha and beta differentially regulate intracellular Ca(2+) dynamics leading to ERK phosphorylation and estrogen neuroprotection in hippocampal neurons. Brain Res. 2007;1172:48–59. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.06.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zaitsu M, Narita S, Lambert KC, et al. Estradiol activates mast cells via a non-genomic estrogen receptor-alpha and calcium influx. Mol. Immunol. 2007;44:1977–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.09.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Micevych PE, Chaban V, Ogi J, Dewing P, Lu JK, Sinchak K. Estradiol stimulates progesterone synthesis in hypothalamic astrocyte cultures. Endocrinology. 2007;148:782–789. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-0774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boulware MI, Weick JP, Becklund BR, Kuo SP, Groth RD, Mermelstein PG. Estradiol activates group I and II metabotropic glutamate receptor signaling, leading to opposing influences on cAMP response element-binding protein. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:5066–5078. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1427-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chaban VV, Micevych PE. Estrogen receptor-alpha mediates estradiol attenuation of ATP-induced Ca2+ signaling in mouse dorsal root ganglion neurons. J. Neurosci. Res. 2005;81:31–37. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levin ER. Integration of the extranuclear and nuclear actions of estrogen. Mol. Endocrinol. 2005;19:1951–1959. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasudevan N, Pfaff DW. Membrane-initiated actions of estrogens in neuroendocrinology: emerging principles. Endocr. Rev. 2007;28:1–19. doi: 10.1210/er.2005-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Razandi M, Pedram A, Greene GL, Levin ER. Cell membrane and nuclear estrogen receptors (ERs) originate from a single transcript: studies of ERalpha and ERbeta expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol. Endocrinol. 1999;13:307–319. doi: 10.1210/mend.13.2.0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Micevych P, Soma KK, Sinchak K. Neuroprogesterone: key to estrogen positive feedback? Brain Res. Rev. 2008;57:470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milner TA, Ayoola K, Drake CT, et al. Ultrastructural localization of estrogen receptor beta immunoreactivity in the rat hippocampal formation. J. Comp. Neurol. 2005;491:81–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang SH, Liu R, Perez EJ, et al. Mitochondrial localization of estrogen receptor beta. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004;101:4130–4135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306948101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedram A, Razandi M, Aitkenhead M, Levin ER. Estrogen inhibits cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro. Antagonism of calcineurin-related hypertrophy through induction of MCIP1. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:26339–26348. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414409200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedram A, Razandi M, Wallace DC, Levin ER. Functional estrogen receptors in the mitochondria of breast cancer cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2006;17:2125–2137. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stefano GB, Prevot V, Beauvillain JC, et al. Estradiol coupling to human monocyte nitric oxide release is dependent on intracellular calcium transients: evidence for an estrogen surface receptor. J. Immunol. 1999;163:3758–3763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang HT, Huang JK, Wang JL, et al. Tamoxifen-induced Ca2+ mobilization in bladder female transitional carcinoma cells. Arch. Toxicol. 2001;75:184–188. doi: 10.1007/s002040100212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang HT, Huang JK, Wang JL, et al. Tamoxifen-induced increases in cytoplasmic free Ca2+ levels in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2002;71:125–131. doi: 10.1023/a:1013807731642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muchekehu RW, Harvey BJ. 17beta-Estradiol rapidly mobilizes intracellular calcium from ryanodine-receptor-gated stores via a PKC-PKA-Erk-dependent pathway in the human eccrine sweat gland cell line NCL-SG3. Cell Calcium. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sessa WC. eNOS at a glance. J. Cell. Sci. 2004;117:2427–2429. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liao X, Liu JM, Du L, et al. Nitric oxide signaling in stretch-induced apoptosis of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Faseb J. 2006;20:1883–1885. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-5717fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Deroo BJ, Korach KS. Estrogen receptors and human disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:561–570. doi: 10.1172/JCI27987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu HP, Shimizu T, Choudhry MA, et al. Mechanism of cardioprotection following trauma-hemorrhagic shock by a selective estrogen receptor-beta agonist: up-regulation of cardiac heat shock factor-1 and heat shock proteins. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2006;40:185–194. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wehrens XH, Marks AR. Altered function and regulation of cardiac ryanodine receptors in cardiac disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2003;28:671–678. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zalk R, Lehnart SE, Marks AR. Modulation of the ryanodine receptor and intracellular calcium. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2007;76:367–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.053105.094237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leung YK, Mak P, Hassan S, Ho SM. Estrogen receptor (ER)-beta isoforms: a key to understanding ER-beta signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:13162–13167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605676103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Poelzl G, Kasai Y, Mochizuki N, Shaul PW, Brown M, Mendelsohn ME. Specific association of estrogen receptor beta with the cell cycle spindle assembly checkpoint protein, MAD2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2000;97:2836–2839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050580997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mize AL, Shapiro RA, Dorsa DM. Estrogen receptor-mediated neuroprotection from oxidative stress requires activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Endocrinology. 2003;144:306–312. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deecher DC, Daoud P, Bhat RA, O'Connor LT. Endogenously expressed estrogen receptors mediate neuroprotection in hippocampal cells (HT22) J. Cell. Biochem. 2005;95:302–312. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sheldahl LC, Shapiro RA, Bryant DN, Koerner IP, Dorsa DM. Estrogen induces rapid translocation of estrogen receptor beta, but not estrogen receptor alpha, to the neuronal plasma membrane. Neuroscience. 2008;153:751–761. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rybalchenko V, Hwang SY, Rybalchenko N, Koulen P. The cytosolic N-terminus of presenilin-1 potentiates mouse ryanodine receptor single channel activity. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2008;40:84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hayrapetyan V, Rybalchenko V, Rybalchenko N, Koulen P. The N-terminus of presenilin-2 increases single channel activity of brain ryanodine receptors through direct protein-protein interaction. Cell Calcium. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morales A, Diaz M, Guelmes P, Marin R, Alonso R. Rapid modulatory effect of estradiol on acetylcholine-induced Ca2+ signal is mediated through cyclic-GMP cascade in LHRH-releasing GT1-7 cells. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;22:2207–2215. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abraham IM, Han SK, Todman MG, Korach KS, Herbison AE. Estrogen receptor beta mediates rapid estrogen actions on gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:5771–5777. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-13-05771.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gingerich S, Krukoff TL. Estrogen in the paraventricular nucleus attenuates L-glutamate-induced increases in mean arterial pressure through estrogen receptor beta and NO. Hypertension. 2006;48:1130–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000248754.67128.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singh M, Dykens JA, Simpkins JW. Novel mechanisms for estrogen-induced neuroprotection. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 2006;231:514–521. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sawai T, Bernier F, Fukushima T, Hashimoto T, Ogura H, Nishizawa Y. Estrogen induces a rapid increase of calcium-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II activity in the hippocampus. Brain Res. 2002;950:308–311. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03186-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pratt WB, Toft DO. Steroid receptor interactions with heat shock protein and immunophilin chaperones. Endocr. Rev. 1997;18:306–360. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.3.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jackson TA, Richer JK, Bain DL, Takimoto GS, Tung L, Horwitz KB. The partial agonist activity of antagonist-occupied steroid receptors is controlled by a novel hinge domain-binding coactivator L7/SPA and the corepressors N-CoR or SMRT. Mol. Endocrinol. 1997;11:693–705. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.6.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lu Q, Pallas DC, Surks HK, Baur WE, Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH. Striatin assembles a membrane signaling complex necessary for rapid, nongenomic activation of endothelial NO synthase by estrogen receptor alpha. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004;101:17126–17131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407492101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chang C, Norris JD, Gron H, et al. Dissection of the LXXLL nuclear receptor-coactivator interaction motif using combinatorial peptide libraries: discovery of peptide antagonists of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:8226–8239. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fan X, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptor beta expression in the embryonic brain regulates development of calretinin-immunoreactive GABAergic interneurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2006;103:19338–19343. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609663103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gamerdinger M, Manthey D, Behl C. Oestrogen receptor subtype-specific repression of calpain expression and calpain enzymatic activity in neuronal cells--implications for neuroprotection against Ca-mediated excitotoxicity. J. Neurochem. 2006;97:57–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03675.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brinton RD. Investigative models for determining hormone therapy-induced outcomes in brain: evidence in support of a healthy cell bias of estrogen action. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 2005;1052:57–74. doi: 10.1196/annals.1347.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cooke BM, Woolley CS. Gonadal hormone modulation of dendrites in the mammalian CNS. J. Neurobiol. 2005;64:34–46. doi: 10.1002/neu.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang L, Andersson S, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptor (ER)beta knockout mice reveal a role for ERbeta in migration of cortical neurons in the developing brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2003;100:703–708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242735799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xu HT, Yuan XB, Guan CB, Duan S, Wu CP, Feng L. Calcium signaling in chemorepellant Slit2-dependent regulation of neuronal migration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2004;101:4296–4301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303893101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tang F, Kalil K. Netrin-1 induces axon branching in developing cortical neurons by frequency-dependent calcium signaling pathways. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:6702–6715. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0871-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Duncan RS, Hwang SY, Koulen P. Differential inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor signaling in a neuronal cell line. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 2007;39:1852–1862. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hwang SY, Wei J, Westhoff JH, Duncan RS, Ozawa F, Volpe P, Inokuchi K, Koulen P. Differential functional interaction of two Vesl / Homer protein isoforms with ryanodine receptor type 1: A novel mechanism for control of intracellular calcium signaling. Cell Calcium. 2003;34/2:177–184. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Westhoff JH, Hwang SY, Duncan RS, Ozawa F, Volpe P, Inokuchi K, Koulen P. Vesl / Homer proteins regulate ryanodine receptor type 2 function and intracellular calcium signaling. Cell Calcium. 2003;34/3:261–269. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]